The Africans who sailed with Columbus, Balboa, and the other major European expeditions in the “age of exploration” helped change the Americas and the world. In 1513 thirty Africans with Balboa hacked their way through the lush vegetation of Panama and reached the Pacific. His men paused to build the first large European ships on the Pacific coast. Africans were with Ponce de León when he reached Florida, and when Cortez conquered Mexico, three hundred Africans dragged his huge cannons in battle. One stayed on to plant and harvest the first wheat crop in the New World.

Africans marched into Peru with Pizarro, where they carried his murdered body to the cathedral. They were with Amalgro and Valdivia in Chile, Alvarado in Educador, and Cabrillo when he reached California. The Europeans destroyed a world, but many Africans peeled away from the devastation to seek a new life. Many found it among Native Americans in Mexico, the Southwest, and elsewhere in the Americas.

The first Africans to enter the chronicles of New World, whom historian Ira Berlin has called “Atlantic Creoles,” were men possessed of extraordinary language skills and familiar with life in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. “Fluent in [the Americas’] new languages, and intimate with its trade and cultures, they were cosmopolitan in the fullest sense,” Berlin wrote of these intercontinental pioneers. Historian Peter Bakker elaborates on their contributions:

Especially in the earliest contact period, Africans were highly valued by Europeans as interpreters with the Native Americans. These men of African origins were not slaves but free black men in the employ of various European trading and exploratory ventures.

The use of Africans as interpreters in trading and exploratory ventures was initiated by the Portuguese in the fifteenth century. Prince Henry the Navigator ordered in 1435 that interpreters be used on all such voyages. Portuguese ships thereafter systematically brought Africans to Lisbon where they would be taught Portuguese so that they could be used to interpret on subsequent voyages to Africa.

The Portuguese strategy was imitated by other Europeans.

In 1540, when Coronado reached “The Cities of Gold,” Africans played a vital role in his expedition. However, artist Harold A. Wolfenlager Jr.’s 1969 painting marginalizes them.

Hired initially as interpreters, negotiators, and ambassadors, many of these Africans settled in the Americas and struck out on their own. In Latin America the Catholic Church celebrated their souls, consecrated their marriages, baptized their children, and buried their remains in hallowed ground. In the seventeeth century, from Angola to Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, African settlers formed religious brotherhoods and self-help societies, and by 1650 Havana, Mexico City, and San Salvador had “Atlantic Creole” communities.

Cherokee mother and daughter, around 1931

In North America “both whites and Indians relied heavily on Negro interpreters” writes historian J. Leitch Wright, Jr., and they were considered “among the most versatile in the world.” Africans proved highly effective in building peaceful relations with Native Americans. In the Carolinas in the 1710s, Timboe, an African, was “a highly valued interpreter” whose role, historian Peter Woods writes, “is emblematic of the intriguing intermediary position occupied by all Negro slaves during these years.”

European officials began to call some Africans impudent and arrogant. They were usually referring to those who successfully advanced their own interests, launched merchant businesses, or became independent career diplomats. Matthieu da Costa, an African, may have visited the site of New York as a translator for the French or Dutch before Henry Hudson’s Half Moon reached it in 1609. Dutch and French officials battled each other in court for the exclusive right to da Costa’s services. In New Amsterdam two years before the Dutch built their first fort, Jan Rodriguez, an African, established a trading post among the Algonquins.

Enslaved Africans were sold from North America to Brazil in 1845.

Brady photograph showing the marriage of two peoples

In their quest for riches, the conquistadores cast the long shadow of slavery on the Americas. On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus recorded in his diary: “I took some of the natives by force.” Six years later explorer John Cabot seized three Native Americans. The European conquest led to a drive to enslave laborers.

In 1520 Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón dispatched two emissaries to South Carolina’s Atlantic coast to build friendship among Native people and locate a site for his colony. Instead, the two seized seventy Native Americans: this made the first European act on what would become U.S. soil the enslavement of free people.

In April 1526, Ayllón sailed to the South Carolina coast to build his dream settlement, San Miguel de Gualdape. He arrived with five hundred Spaniards and one hundred African laborers. But mismanagement, disease, and Indian hostility dogged his colony for six months and took Ayllón’s life. Then Indian resistance and slave defiance tore it apart, and the surviving Europeans retreated to Santo Domingo. The remaining Africans joined with neighboring Native Americans, and together they created the first permanent U.S. settlement to include people from overseas. Their peaceful colony, marked by friendship and cooperation between foreigners and newcomers, introduced an American legacy not born of conquest. The conquistadores soon overran San Miguel de Gualdape, but it came to have many models in the Americas.

This antique print, entitled America, used dancing to show peaceful relations between Africans and Native Americans.

Native Americans were the first people enslaved by Europeans in the New World, but they died by the millions of foreign diseases, overwork, and cruelty. European merchants turned next to Africa and seized its strongest men, women, and children to perform the hard work of the new lands.

This meant that Indian and African people first met in the slave huts, mines, and plantations of the Americas. In 1502 Nicolas de Ovando, the new governor of Hispaniola, Spain’s headquarters in the Caribbean, arrived in a flotilla that carried the first enslaved Africans. Within a year Ovando reported to King Ferdinand his Africans had escaped, found a new life among the Native Americans, and “never could be captured.” He was describing an American tradition earlier than the first Thanksgiving.

In the following decades enslaved Africans and Indians escaped bondage together and began to unite against the common foe. Anthropologist Richard Price studied the sacred legends of the Saramaka people of Dutch Guiana, now Suriname, which date back to 1685. In one, Lanu, an African slave who would become a leader of the Saramakas, escaped, and Wamba, the Indians’ forest spirit, entered his mind to lead him to a Native village. “The Indians escaped first and then, since they knew the forest, they came back and liberated the Africans,” concluded Price.

Once free of the European conquerors, Africans and Native Americans found they had more in common with each other than with a foe wielding muskets and whips. For both peoples the spiritual and environmental merged. Religion was not confined to a single day of prayer but was a matter of daily reflection and action. Africans and Indians believed that community needs, not private gain, should determine judicial, economic, and life decisions. Both accepted an economy based on cooperation, and were baffled by the conqueror’s passion to accumulate wealth.

A successful slave rebellion in Haiti in the 1790s convinced Napoleon that France could not hold its American empire. In 1803 he sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States for four cents an acre.

During the conquest the two peoples brought each other important gifts. The Middle Passage and enslavement gave Africans a multidimensional understanding of European goals, diplomacy, and weaponry. To Native Americans they brought their knowledge of the foe’s plans, weaknesses, and often valuable arms and ammunition. Native American societies offered Africans a red hand of friendship, a refuge, a new life – and a base for insurgency.

In the early decades of the sixteenth century, slave revolts in Colombia, Cuba, Panama, and Puerto Rico often found Africans and Native Americans acting in unison. In 1537 Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza of Hispaniola told of a major rebellion that threatened Mexico City, saying the Africans “had chosen a king, and… the Indians were with them.” By 1570 Spanish colonial officials admitted that one in ten slaves were living free. Viceroy Martin Enriquez later warned, “the time is coming when these [African] people will have become masters of the Indians, inasmuch as they were born among them and their maidens and are men who dare to die as well as any Spaniard.”

In the Southwest, Africans joined the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 as leaders and soldiers, helping to drive out Spain’s armies and missionaries and freeing the region for a dozen years. Decades before fifty-five white men met in Philadelphia in 1776 and wrote the Declaration of Independence, people of color in the continent had revolted against foreign rule, injustice, and slavery. They became the first freedom fighters of the Americas.

A runaway is captured in the French colonies.

“Division of the races is an indispensable element,” warned a Spanish official. European governors constantly sought to destroy the alliances in the woods with tactics of divide and rule. In 1523 Hernando Cortez enforced a royal order in Mexico that banned Africans from Indian villages. In 1723 Jean-Baptiste LeMoyne de Bienville, founding governor of Louisiana, urged that putting “these barbarians into play against each other is the sole and only way to establish any security in the colony.” In 1776 U.S. Colonel Stephen Bull, saying his policy was to “establish a hatred” between the two races, dispatched Indians to hunt Black runaways in the Carolinas.

Staggering rewards were offered to Africans to fight Indians and Indians to fight Africans. In the Carolinas Native Americans were bribed with three blankets and a musket, and in Virginia it was thirty-five deerskins. Governor Perier of Louisiana offered Indians two muskets, two blankets, twenty pounds of balls, four shirts, mirrors, knives, musket stones, and four lengths of cloth for the recapture of a single runaway. Local warriors often refused to hunt runaways, so Europeans had recruit people from distant regions. “Between the races we cannot dig too deep a gulf,” stated a French official.

In 1708 British colonials deployed mounted slave cattle-guards to protect colonial Charleston from Indians. On Virginia’s frontier George Washington hired African American “pioneers or hatchet men.” In 1747 the South Carolina legislature thanked its militiamen of African descent who “in times of war, behaved themselves with great faithfulness and courage, in repelling the attacks of his Majesty’s enemies.” But the legislature limited the number of Black men to a third of the total to ensure they would always be outnumbered by armed whites.

Despite divide-and-rule strategies, the lid never closed. In 1721 the governor of Virginia had the Five Nations sign a treaty and promise to return all runaways; in 1726 the governor of New York had the Iroquois Confederacy make a similar promise; in 1746 the Hurons promised and the next year the Delawares promised. None, reports scholar Kenneth W. Porter, returned a single slave.

Slaveholders such as George Washington brought enslaved people to the frontier. Once there, many Africans took the opportunity to learn Indian languages and to escape.

What for European merchants and planters was a matter of profits had taken on another meaning for Native Americans. They would not sunder the bonds between husband and wife, parent and children, relatives and loved ones. Lacking racial prejudice, Native Americans had welcomed Africans into their villages, then their homes and families. This became clear to careful observers. Thomas Jefferson discovered among Virginia’s Mattaponies “more negro than Indian blood.” Artist George Catlin found that “Negro and North American Indian, mixed, of equal blood” were “the finest built and most powerful men I have ever yet seen.”

African Choctaw in Mississippi photographed in 1908

To the sputtering fury of European planters, two dark peoples were not only standing as families but uniting as allies. During Pontiac’s War in 1763, a white settler in Detroit complained, “The Indians are saving and caressing all the Negroes they take” and warned that this could “produce an insurrection.” Africans and Indians faced regimes more mercilessly cruel than the one denounced in the Declaration of Independence. The two peoples of color had to fight off slave-hunting posses dispatched by the men who wrote the great charter of liberty.

Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant

Carter G. Woodson, father of modern African American history, would call this genetic mixture of people of color “one of the longest unwritten chapters in the history of the United States.” It also produced a number of talented persons. One gifted individual to emerge from this relationship was Wildfire, born in 1846 in upstate New York to a Chippewa mother and African American father. Until her teenage years she lived with her mother’s people; later she attended Oberlin College and began, as Edmonia Lewis, to pursue a career in art and sculpture.

Wildfire, or Edmonia Lewis, became the first important sculptor of African and American Indian descent.

One of the most interesting individuals I met at the reception was Edmonia Lewis, a colored girl about twenty years of age, who is devoting herself to sculpture. … I told her I judged by her complexion that there might be some of what was called white blood in her veins. She replied, “No; I have not a single drop of what is called white blood in my veins. My father was a full-blooded Negro, and my mother was a full-blooded Chippewa…”

“And have you lived with the Chippewas?”

“Yes. When my mother was dying, she wanted me to promise that I would live three years with her people, and I did.”

“And what did you do while you were there?”

“I did as my mother’s people did. I made baskets and embroidered moccasons and I went into the cities with my mother’s people, to sell them…”

“But, surely,” said I, “you have had some other education than that you received among your mother’s people, for your language indicates it.”

“I have a brother,” she replied, “who went to California, and dug gold. When I had been three years with my mother’s people, he came to me and said, ‘Edmonia, I don’t want you to stay here always. I want you to have some education.’ He placed me at a school in Oberlin. I staid there two years, and then he brought me to Boston, as the best place for me to learn to be a sculptor. I went to Mr. Brackett for advice; for I thought the man who made a brist of John Brown must be a friend to my people. Mr. Brackett has been very kind to me.”

She wanted me to go to her room to see… a head of Voltaire. “I don’t want you to go to praise me,” she said, “for I know praise is not good for me. Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don’t want that kind of praise. I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something.”

L. Maria Child, letter, The Liberator, February 19, 1864

From the Atlantic to California – where these two men lived – Africans and Indians united against the European conquest.

After the Civil War Lewis had a studio in Rome where she produced works based on African and Native American themes. In the next decade her art was sold all over Europe and the United States, and in 1876 her twelve-foot-tall, two-ton Death of Cleopatra, exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, was called “the grandest statue in the Exposition.”

The Great Dismal Swamp was home to many runaways.

From the misty dawn of America’s earliest foreign landings, Africans who fled to backwoods regions created their “maroon” (after a Spanish word for runaway) settlements. Europeans saw “maroons” as a knife poised at the heart of their slave system, even pressed against their thin line of military rule. They had a point.

For the daring men and women who built these outlaw communities, however, they were a pioneer’s promise. During his first two weeks in the New World, Columbus’s diary included the word “gold” seventy-five times. Africans sought something more valuable. From the Great Dismal Swamp to the Florida Everglades, African and Native American maroon enclaves posed a fortified alternative to foreign domination. They served as beacons to discontented plantation slaves and drove slaveholders to fuming anger. They were agricultural and trading centers with armies, and bore names such as “Disturb Me If You Dare” and “Try Me If You Be Men.” Maroon songs resonated with pride and defiance: “Black man rejoice/White man won’t come here/And if he does/The Devil will take him off.”

Guerrilla fighters, such as this Jamaican, fled slavery and picked up European muskets.

In 1719 a Brazilian colonist wrote to King Joao V of Portugal: “Their self-respect grows because of the fear whites have of them.” Some maroon settlements, too well hidden and ably defended to be conquered, became trade partners rather than enemies. Many opened commercial relations with slaveholders or other foes, and had slave intermediaries sell their products in local markets.

The Republic of Palmares in northeastern Brazil, founded in the early 1600s by Africans and Indians, became the strongest maroon enclave in the Americas. Courts of justice reigned, children were educated, the elderly were cared for, and a common defense was created under an African form of government. Palmares’s monarch, Ganga-Zumba, derived his name from an Angolan word for “great” and a Tupi Indian word for “ruler.” By the 1650s the people of Palmares huddled behind their three large wooden walls, fending off Dutch and Portuguese military assaults about every fifteen months.

Two generations later Palmares had ten thousand men, women, and children and constituted one of the largest cities in the Americas, its population twice the size of New York City. Finally, on February 5, 1694, after a forty-two day siege, the walled city was overrun by the Portuguese. White officers not only leveled Palmares as an enemy base but tried to destroy it as a legendary flame of liberty.

The defeat of Palmares coincided with the birth of a new kind of maroon community. Before 1700 maroon settlements were generally ruled by Africans, but after that they were more likely to be governed by children born of African-Native American marriages.

Women played a vital role in maroon settlements. Often in short supply, they were sought as revered wives and mothers who would provide the stability of family life and children, the community’s future. Two African women ruled maroon settlements in colonial Brazil. Fillipa Maria Aranha governed a colony in Amazonia, where her uncommon military prowess convinced Portuguese officials it was wiser to negotiate than try to defeat her armies. Aranha was able to win independence, liberty, and sovereignty for her people. In Passanha, an African woman of unknown name successfully hurled her Malali Indian and African guerrilla troops against European soldiers.

They rejoiced exceedingly at our happiness in thus being favored by the Great Spirit, and felt very grateful that we had condescended to remember our red brethren in the wilderness. But they could not help recollecting that we had a people among us, whom, because they differed from us in color, we had made slaves of, and made them suffer great hardships, and lead miserable lives. Now they could not see any reason, if a people being black entitled us thus to deal with them, why a red color should not equally justify the same treatment. They therefore had determined to wait, to see whether all the black people amongst us were made thus happy and joyful before they would put confidence in our promises; for they thought a people who had suffered so much and so long by our means, should be entitled to our first attention; and therefore they had sent back the two missionaries, with many thanks, promising that when they saw the black people among us restored to freedom and happiness they would gladly receive our missionaries.

Dr. Elias Boudinot, cited in Adam Hodgson, Remarks During a Journey Through North America in the Years 1819, 1820, and 1821 (New York, 1823), pp. 218–220.

British merchants, as part of the plan to seal off Native villages from escaping slaves in North America, introduced African slavery to the Five Civilized Nations: the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles. Their divide-and-rule tactic worked less than perfectly. In 1765, John Bartram, a famous botanist, found that Native American bondage permitted slaves to marry masters and find “freedom… and an equality.” But European intrusions had begun to infect Native American societies, undermining their values, creating racial conflict and class divisions, and producing leaders interested in private gain.

Between the American Revolution and the Civil War, however, in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Tennessee, Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and the Carolinas, African Americans, slave and free, often found friendship and a ready adoption among Native Americans. In 1843 whites in Virginia complained to their legislature about the Pamunkeys: “Not one individual can be found among them whose grandfathers or grandmothers one or more is not of Negro blood.” The New York legislature announced its Montauk and Southampton Indians “are only Indian in name.” Along the Atlantic coast Native Americans were transformed into a biracial people.

On the Florida peninsula Africans and Native Americans developed a unique and dramatic relationship unmatched in the rest of the country. It began with the last decades of the seventeenth century, when enslaved Africans held on British colonial plantations in the Carolinas fled south. Spanish Florida, often at war with England, granted runaways “complete liberty,” and in 1693 the Spanish government issued an edict of liberation designed to draw off enslaved workers from the British. When white masters arrived in St. Augustine to reclaim slaves, they were confronted by Black men and women who taunted them.

By 1739 Florida officials placed Francisco Menendez, an African Mandingo, in command of the key garrison of Fort Mose, his assignment to protect St. Augustine from attack. Fort Mose became the first town governed by people of African descent in North America. In 1740 Menendez’s forces helped repulse an invasion led by Georgia governor James Oglethorpe.

When the Seminoles, fleeing persecution as a part of the Creek Nation, fled to Florida at the time of the American Revolution, Africans did more than welcome them. Scholar Joseph Opala claims they taught the newcomers methods of rice cultivation they had learned in Sierra Leone and Senegambia. Then, on this basis, the two peoples formed an agricultural and military alliance that reconstructed the Seminoles as a multicultural nation.

This German print from the 1590s shows people of Florida with an African leader.

Red and Black Seminoles built homes, tended land and flocks, raised families, and provided for the common defense. Though some Africans chose to live in separate villages, intermarriage also marked the Seminole nation. In 1816, U.S. Colonel Clinch reported on the extent of Seminole settlements along the Appalachicola River: “Their corn fields extended nearly fifty miles up the river and their numbers were daily increasing.” By this time Colonel Clinch was leading a combined force of Creek mercenaries, regular U.S. Army troops, and U.S. Navy vessels against this alliance.

Since Seminole encampments in Florida appeared to threaten Southern plantations, the U.S. government and planters launched slave-hunting incursions. Finally, in 1819, the United States purchased Florida from Spain to end what General Andrew Jackson called “this perpetual harbor for our slaves.”

Washington quickly found itself embroiled in tropical war against a seasoned foe defending its homeland. The “Second Seminole War” of the 1830s cost $40 million, 1,500 American lives, and at times tied up half of the U.S. Army. “The two races, the negro and the Indian, are rapidly approximating; they are identical in interests and feelings…” was commander Major General Thomas Sidney Jesup’s perceptive evaluation of the Seminoles.

In the Florida Everglades, African Americans defended their new, free communities.

In 1837 Jesup concluded: “This, you may be assured, is a negro, not an Indian war; and if it be not speedily put down, the south will feel the effects of it on their slave population before the end of the next season.” Jesup found the source of Seminole strength easy to identify: “The warriors have fought as long as they had life, and such seems to be the determination of those who influence their councils – I mean the leading negroes.”

Creek mercenaries captured Black Seminoles from Florida around 1816.

This is a U.S. version of the warfare in Florida in the 1830s.

John T. Sprague, a U.S. soldier who fought in the war, confirmed Jesup’s judgment: “The negroes exercised a wonderful control. They openly refused to follow their masters, if they removed to Arkansas. … In preparing for hostilities they were active, and in the prosecution blood-thirsty and cruel. It was not until the negroes capitulated, that the Seminoles ever thought of emigrating.”

“The negroes rule the Indians, and it is important that they should feel themselves secure; if they should become alarmed and hold out, the war will be renewed,” Jesup warned his superiors in Washington. However, U.S. burn-and-destroy operations, the seizure of hostages, and bribery eventually persuaded a war-weary Seminole Nation to accept removal to the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

In the Indian Territory the Seminole Nation faced slave-hunting raids by whites and their old Creek enemies. Finally, in 1849 Wild Cat and African Seminole chief John Horse led hundreds of Seminoles across Texas to Mexico. There General Santa Anna welcomed them and hired their young men as “military colonists” to protect the Rio Grande border.

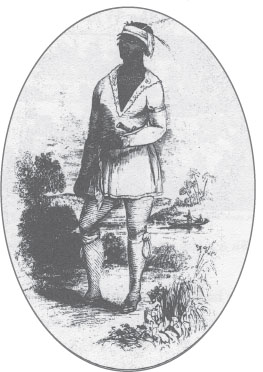

“Negro Abraham” was a leading Seminole interpreter and diplomat when this delegation visited Washington, D.C., in 1824.

The African Seminoles, Kenneth W. Porter notes, had mounted “the most serious Indian war in the history of the United States”; he adds that it “should rather be described as a Negro insurrection with Indian support.” In Florida cooperation between Africans and Indians reached its flowering. The Seminole alliance mounted the stongest maroon insurgency, and the most resolute armed resistance to human bondage, in the United States.

The multicultural Seminole Nation had announced that people of color in the Americas would fight until they were free.

John Horse, chief of the Black Seminole Nation, shown in 1835. He lived until 1882.

The first African whose name appears in the historical chronicles of the New World, an explorer of many skills, was Estevan, born in Azamore, Morocco, at the beginning of the sixteenth century. He was the servant of Andres Dorantes and has variously been called Estevanico, Stephen Dorantes, and Esteban. Little is known about his life until June 17, 1527, when Estevan, then about thirty, and his owner boarded a ship in San Lucas de Barrameda, Spain, bound for the Americas. Both men joined a five-hundred-man expedition to explore the northern shore of the Gulf of Mexico, an assignment authorized by King Charles I and under the command of Florida governor Pánfilo de Narváez.

Wild Cat, staunch friend of the Black Seminoles

On April 14, 1528, the Narváez expedition probably landed at Sarasota Bay and immediately floundered on a combination of inept management and natural calamities. Starving members resorted to cannibalism, followed by mass desertions. In one Native American village, which they would rename “Misfortune Island,” disease reduced the party to fifteen. Finally only four were left: Estevan, his master, and two other Spaniards.

The four were enslaved by Indian tribes, but this may have saved their lives. During a semiannual Indian gathering the men met and, like slaves anywhere, began to plot their escape. At the next gathering the foreigners escaped together, plunging westward along the Gulf Coast.

The record of their eight years of wandering was recorded by Cabeza de Vaca, their leader. He told how Estevan posed as a medicine man, conducted minor surgery, and learned local languages quickly, and how his skills and diplomacy helped the four gain food and water and find their way. Estevan, Cabeza de Vaca wrote, “was our go-between; he informed himself about the ways we wished to take, what towns there were, and the matters we desired to know.” In 1536, eight years after the Narváez party landed in Florida, Estevan led the four to Spain’s headquarters in Mexico City.

The three white men had had enough of the Americas and left for Spain. Before he departed, Andres Dorantes sold Estevan to Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza of New Spain. Estevan’s stories, embellished from Indian tales about Cibola, or the Seven Cities of Gold, enthralled the governor, particularly when he produced metal objects to demonstrate that smelting was an art known in Cibola.

In 1539 Governor Mendoza selected Father Marcos de Niza, an Italian priest, to lead his expedition to Cibola, and Estevan was chosen as guide. The African was sent ahead with Indian scouts and two huge greyhounds, and instructed to send back wooden crosses whose size would indicate progress toward Cibola. Estevan, this time bearing a large gourd decorated with strings of bells and a red-and-white feather as a sign of peace, again posed as a medicine man. Some three hundred Native American men and women joined the mysterious and confident African.

One by one, huge white crosses began to arrive in Father Marcos’s camp carried by Estevan’s guides, who reported that his party, growing in size, was being showered with jewelry and gifts. There was also the evidence of the crosses: each was larger than the last, and every few days another arrived. Father Marcos quickened his march to Cibola. But suddenly there was no further word from Estevan. Then two wounded Indian scouts arrived to tell of Estevan’s capture and the massacre of his force as they were about to enter an Indian village. They concluded, “We could not see Stephen any more, and we think they have shot him to death, as they have done all the rest which went with him, so that none are escaped but we only.” Perhaps he was dead or perhaps Estevan had concocted a clever story, and like many an enslaved African, made his escape.

In this Jay Datus mural, Estevan is shown with his Native American companions in 1539.

Estevan’s story does not end there. He became the first foreigner to explore Arizona and New Mexico, and legends of his journey led to the explorations of Coronado and de Soto. He brought three races together in the Americas and paved the way for the European settlement of the Southwest.

So the sayde Stephan departed from mee on Passion-sunday after dinner: and within foure dayes after the messengers of Stephan returned unto me with a great Crosse as high as a man, and they brought me word from Stephan, that I should forthwith come away after him, for hee had found people which gave him information of a very mighty Province, and that he had sent me one of the said Indians. This Indian told me, that it was thirtie dayes journey from the Towne where Stephan was, unto the first Citie of the sayde Province, which is called Ceuola. Hee affirmed also that there are seven great Cities in this Province, all under one Lord, the houses whereof are made of Lyme and Stone, and are very great…

Father Marcos de Niza in Richard Hakluyt, Hakluyt’s Collection of the Early Voyages, Travels, and Discoveries of the English Nation (London, 1810)

America’s earliest Atlantic coast frontiers were to the north and south, in Florida and northern New England. In 1735, when five-year-old Lucy Terry was seized in Africa and sold in Deerfield, Massachusetts, the little town stood on the edge of land that stretched from the British colonies to French Canada and was still controlled by Native Americans.

A Rhode Island school for Native Americans and African Americans, around 1860

Of Lucy and the man she would marry, historian George Sheldon has written, “In the checkered lives of Abijah Prince and Lucy Terry is found a realistic romance going beyond the wildest flights of fiction.” At the time of their marriage in 1756, he was forty-six. She was twenty-one and had won local acclaim for a ballad she had written when she was sixteen, about a battle with Indians near Deerfield, at a place called The Bars. Her rhymed description of “The Bar’s Fight” is the first published poem by an African American, and still is considered the most accurate version of the event.

Abijah Prince had distinctions of his own: For four years he served in the militia during the clash of colonial empires known as King George’s War. He later gained his liberty either by this military service or through a grant of his master, and he also obtained his wife’s freedom. His original master gave him three valuable parcels of land in Northfield, Massachusetts, and another employer gave him a hundred-acre farm in Guilford, Vermont. By his own application to George III and the governor of New Hampshire, Prince became one of the fifty-five original grantees and founders of the town of Sunderland, Vermont, where he owned another hundred-acre farm.

Two of the Princes’ sons saw service in the American Revolution. Caesar, the eldest, served in the militia, and Festus, a fifteen-year-old, falsified his age and served for three years as an artilleryman and a horse-guardsman.

But wartime patriotism did not exempt Abijah and Lucy from peacetime bigotry. In 1785 their farm at Guilford became the target of a wealthy white neighbor, who tore down fences and set haystacks afire. Abijah, close to eighty, stayed at home while Lucy crossed the state on horseback to carry their protest to the governor’s council. Though they were aware of the political influence of her wealthy antagonists, the council listened to her plea and on June 7, 1785, found in her favor. Never before had an African American woman challenged the power structure with such success.

However, Lucy Prince tasted defeat when she tried to enroll her youngest son, Abijah, Jr., in the new Williams College. For three hours she addressed the trustees, citing her family’s contributions to the Revolution, and her friendship with Colonel Elijah Williams, who had officiated at her own wedding and whose will had established the college. “Quoting an abundance of law and Gospel, chapter and verse,” she supported her plea, reported a historian of the time, “but all in vain.” The trustees informed her that they had no intention of altering their prohibition against admission of students of color.

Lucy rose again to plead for her right to equal justice before white men. This time she argued a boundary-line dispute with a neighbor who sought to claim part of the Sunderland property Abijah had been granted by George III. Lucy entered Vermont’s supreme court advised by Isaac Ticknor, U.S. senator, jurist, and for many years Vermont’s governor. Opposing counsel was Royall Tyler, the country’s first playwright-novelist, and later chief justice of Vermont’s high court, assisted by a legal giant of the Vermont bar, Stephen Row Bradley.

The boundary contest was probably heard by Dudley Chase of Vermont’s highest court, though there is uncertainty about the identity of the presiding judge. There is no uncertainty about what the jurist said to the woman in whose favor he ruled: “Lucy made a better argument than he had heard from any lawyer at the Vermont bar.” Again she had confronted the powerful, and again she had won.

Abijah died in 1794, and Lucy in 1821 at ninety-one. They had six children. In each of her last eighteen years she rode horseback over the mountains from Sunderland to visit her old friends and her husband’s grave on their old Guilford farm.

By 1803 Lucy Prince had lost the farm to the same fence-destroying, haystack-burning neighbors whom she had defeated at the governor’s council. The year Lucy died the Massachusetts legislature established a committee to determine whether to pass a law expelling Black emigrants. Cotton had become king and, in strengthening the bonds of slavery, it had weakened claims of free African Americans to equal justice.

Perhaps the frontier experiences of Lucy and Abijah Prince proved that African Americans has less to fear from armed Native Americans than white barn-burning neighbors, college trustees, and state legislators.

August ’twas the twenty-fifth

Seventeen hundred forty-six

The Indians did in ambush lay

Some very valient men to slay

Twas nigh unto Sam Dickinson’s mill,

The Indians there five men did kill

The names of whom I’ll not leave out

Samuel Allen like a hero fout

And though he was so brave and bold

His face no more shall we behold

Eleazer Hawks was killed outright

Before he had time to fight

Before he did the Indians see

Was shot and killed immediately

Oliver Amsden he was slain

Which caused his friends much grief and pain

Simeon Amsden they found dead

Not many rods off from his head.

Did lose his life which was so dear

John Saddler fled across the water

And so escaped the dreadful slaughter

Eunice Allen see the Indians comeing

And hoped to save herself by running

And had not her petticoats stopt her

The awful creatures had not cotched her,

And tommyhawked her on the head

And left her on the ground for dead.

Young Samuel Allen, Oh! lack-a-day

Was taken and carried to Canada