Slavery marched into the West as a result of repeated compromises with slaveholders. These began in the summer of 1787, when representatives of the new United States met, some in New York City and others in Philadelphia, and “settled” the slavery issue. In New York the Continental Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, which included an article that forbid human bondage in states to be carved out of the Ohio Valley. And in Philadelphia fifty-five men wrote the U.S. Constitution, which protected slave property and granted exceptional powers to slaveholders.

Northern states had begun the process of emancipation during the Revolution. But in 1792 the invention of the cotton gin revitalized the South’s “peculiar institution.” Slaves soon constituted the country’s largest financial asset, and a slaveholding elite wielded a political whip over eleven Southern states and all three branches of the new government.

At the Constitutional Convention men talked eloquently of liberty and justice, but many delegates were either slaveholders or represented Northern businesses dependent on profits from the slave trade and the plantation economy.

Until the election of Abraham Lincoln, slaveholders dominated the federal government. Two-thirds of the time they controlled the White House, the Speaker of the House, and the president of the Senate. Twenty of thirty-five Supreme Court Justices were proslavery Southerners.

Embarrassed that every fifth American was enslaved, the Founding Fathers, at James Madison’s request, wrote a document that did not use the word “slave” and instead used such euphemisms as “other persons” or “persons held to labor.” The Constitution failed to stem the slaveocracy. It also highlighted the gulf between promise and democratic performance in America, forever tarnished the claims of its creators, and ensured, as Lincoln said in 1864, that “with every drop of blood drawn the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.”

The shadow of slavery lengthened across the land with the first treaty signed under the new Constitution. In Section III of the Creek Nation Treaty of August 1, 1790, the U.S. government required the return of slave runaways among the Creeks.

The Northwest Ordinance ban on slavery had its first test when a Black couple owned by Judge Henry Vandenburgh in the Ohio Territory sued in court for “illegal enslavement.” Judge George Turner ordered their immediate release, but Vandenburgh seized them. Turner then appealed to Arthur St. Clair, the newly arrived territorial governor, who had played a leading role in passage of the Northwest Ordinance. St. Clair used his high office to wave aside the Ordinance’s clear antislavery meaning. He stated it did not apply to people enslaved before 1787. This left the couple in bondage and it allowed masters to bring thousands of people to the Ohio Valley as slaves, and opened a western path to the Civil War.

Slaveholders in the Ohio Territory began to clamor for a legal return of bondage, and between 1803 and 1807 the Indiana territorial legislature three times passed laws permitting retention of slaves as “indentured servants.” By 1810 the Indiana and Illinois territories listed 405 indentured men and women, and by 1820 Illinois alone had 917 – individuals who had been forced to sign thirty- to ninety-nine-year contracts of indenture. Kentuckian William Henry Harrison, Indiana’s first territorial governor and later a president of the United States, was among the first to import “indentured servants.”

The slavery issue brought Illinois to the verge of armed conflict. Violent disputes, reported Judge Gillespie, an eyewitness, “for fierceness and rancor excelled anything ever before witnessed. The people were at the point of going to war with each other.” Another Illinois citizen reported: “Old friendships were sundered, families divided and neighborhoods arrayed in opposition to each other. Threats of personal violence were frequent, and personal collisions a frequent occurrence. As in times of warfare, every man expected an attack, and was prepared to meet it.”

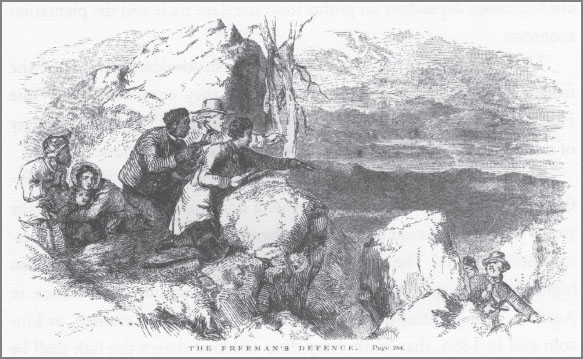

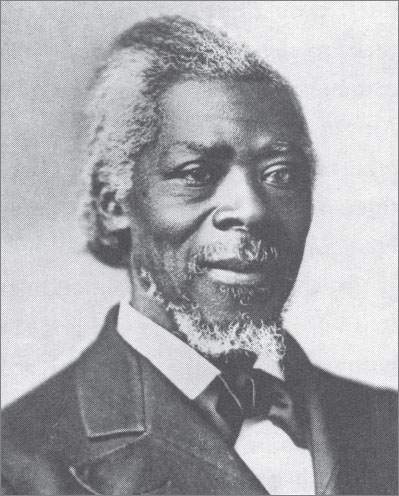

An abolitionist sketch shows armed resistance by fugitives and their white allies. The illustration is from the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

By 1822 proslavery forces had elected a lieutenant governor, controlled both houses of the legislature, and demanded a constitutional convention to legalize slavery. Governor Reynolds wrote: “The convention question gave rise to two years of the most furious and boisterous excitement and contest that ever was visited on Illinois. Men, women and children entered the arena of party warfare and strife, and the families and neighborhoods were so divided and furious in bitter argument against one another, that it seemed a regular civil war might be the result.”

Enslaved men and women in the territories waged their own battle for freedom. In 1807 in frontier Detroit, Peter and Hannah Denison, learning that their master’s will freed them, sued for the liberty of their eight children. When a court rejected their plea, friends helped two of their children, Elizabeth and Scipio, escape to Canada.

African American women struggled to be free in Western territories and states. Some escaped, others worked at extra jobs to pay for their liberty, and still others hired attorneys and sued for freedom in the judicial system.

When Indiana entered the Union in 18116 as a state, fifteen “indentured” African Americans sued for their liberty, but only one was successful. When Mary Clark brought her case to trial a document was produced showing that in 1821 she had signed an indenture. The Ohio Supreme Court ruled that since her suit “declared her will,” this proved she was held against her will, and she became a free woman.

Over a forty-year period that began in 1820, the federal Circuit Court in St. Louis, Missouri, heard 200 cases in which enslaved people sued for freedom, and 120 of the cases were brought by women. Some women in St. Louis took illegal action. In 1824, Caroline Quarelles, sixteen, decided to flee the city after her owner cut off her long black hair. As she fled to Wisconsin, a $300 reward notice was posted for her capture and a posse rode in pursuit. Ever resourceful, Quarelles took a steamboat to Alton, Illinois, a stagecoach to Milwaukee, and from there was guided by Underground Railroad agents to Detroit and then Canada.

In 1866 fugitive slave Elizabeth Denison returned to live in Detroit. In her will she left $1,500 to her church.

In Indiana, women repeatedly appealed to the courts to nullify their indentures. In Harrison County a Kentucky slave sued her master for assault and false imprisonment and a jury awarded her liberty and $14. In 1816, Lydia, born in Indiana and sold three times, brought suit and finally was freed by the Indiana Supreme Court. In 1820 a slave named Polly hired an attorney and sued her master; acting on her appeal, the Indiana Supreme Court freed Polly and ended slavery in the state.

Some battles ended in bloodshed. In 1856 Margaret Garner and her children crossed the Ohio river from Kentucky with seventeen other fugitives. Surrounded by a posse, Garner killed one of her children rather than see her return to slavery. When she was shipped back to Kentucky, Garner drowned another child. Later, after she ended her own life, her husband reported, “and is free.”

The first Texans of African descent were not enslaved but free, and some were ranchers in the sprawling Mexican province. In 1810 Narciso la Baume had a ranch near Nacogdoches, and Pedro Ramirez herded cattle along the San Antonio River.

Mexico began to move toward emancipation soon after it freed itself of Spanish control, in 1811. But matters changed in the early 1820s, when Mexico invited U.S. citizens to settle in Texas if they agreed to become Catholics and accept its ban on slavery. Defiant Southern slaveholders brought along thousands of slaves, some insisting they were “indentured servants.” By 1836, when settlers declared Texas free, enslaved African Americans were a fourth of the population, and fourteen East Texas counties had an enslaved population of 50 percent or more.

The Lone Star Republic was annexed by the United States in 1845. The new state’s economy was based on slave labor, and the Texas House of Representatives called its 5,000 slaves “the happiest… human beings on whom the sun shines.” Those in chains spoke differently: “Slavery time was hell!” said Mary Gaffney. At thirteen Jeff Hamilton was sold in an auction: “I stood on the slaveblock in the blazing sun for at least two hours… my legs ached. My hunger had become almost unbearable… I was filled with terror, and did not know what was to become of me. I had been crying for a long time.” Cotton labor in East Texas began at sunup and did not end until sundown. “You went out to the field almost as soon as you could walk,” recalled Adeline Marshall.

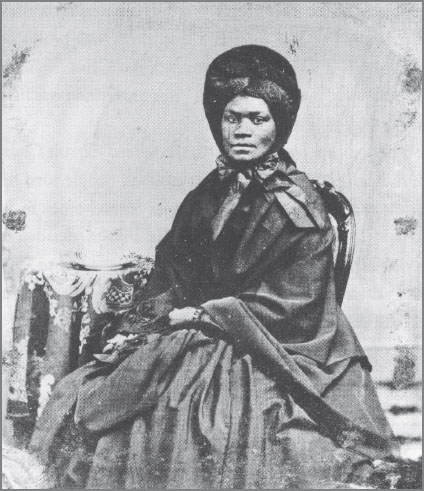

Rhoda Beaty, enslaved in Jasper County, was a free person when she moved to Travis County, Texas.

Some enslaved people were house servants, midwives, skilled artisans, and others helped to run ranches and plantations. Some were cowhands. “I doubt if Texas has ever seen finer cowboys than those black men,” recalled Nan Alverson of her father’s ranch near Fort Worth. Near Hondo in the 1850s, Moses Brackens was proud of his cowhand talents: “Bout the only way I’d get throwed was to get careless.”

Enslaved men and women tried to resist harsh conditions, preserve families, and improve their lives. In 1846 nineteen slave and free men and women inaugurated Galveston’s First Colored Baptist Church. In 1858 Mrs. M. L. Capshaw, a white woman, taught reading and writing classes in the African Methodist Church, and by 1860 an estimated 5 percent of Texas’s 186,000 slaves could read.

Masters such as Mary Maverick claimed to be kind and fair, but found people just wanted to be free: “I have owned many slaves, yet I can’t see that one loves me or cares consistently to please me.”

Some enslaved people sued to gain liberty. In 1838 in Harris County, Sally Vince brought Allen Vince to court for holding her in bondage after her owner’s will had bestowed liberty. A county judge freed her and ordered Allen to pay court costs. In 1847, also in Harris County, when Emeline and her two children sued for liberty, a white jury ruled in their favor, and awarded Emeline liberty and $1 in damages.

Victoria C. Lofton was born into slavery in Kaufman County, Texas.

Resistance often turned violent. “Aunt Angeline,” a relative recalled, battled “anybody that tried to whip her.” Reward notices for runaways reveal tales of pain and defiance: “Bill [twenty-eight]… a bright mulatto knocked down the overseer” and “ran off with a double-barrell shotgun.” Martin, a forty-eight-year-old blacksmith, fled with whip marks on his back, neck, and both temples. When Tempie Cummings and her mother ran away, their owner fired at them. With bullets whizzing over their heads, they slid down a ravine and escaped.

In 1850, though Rachel was pregnant, she and two other armed slaves fled to Mexico. By the Civil War Mexico’s Black Texan population had risen to four thousand, and a white U.S. visitor described them as among the healthiest and most intelligent people he had ever seen. But planters, such as John “Rip” Ford, were furious: “Slaves are treated with respect and with more consideration than either [white] Americans or Europeans.”

Ford and others led raids across the border to seize fugitives. U.S. presidents James Polk and Zachary Taylor pressured Mexico to extradite runaways, but Mexican officials replied: “No foreign government would be allowed to touch a slave who had sought refuge in Mexico.” Pitched battles and heated diplomatic exchanges kept the Rio Grande border in turmoil.

An African American woman is among those waiting outside a post office in the Texas panhandle. (Date unknown)

Slavery was both legal and important to the economy of Utah. In 1847 Reverend Brigham Young led members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, known as the Mormons, from Eastern states to sanctuary in Salt Lake City. Since its founding in 1830, African Americans, slave and free, had been recruited by the church.

Among the pioneer Mormon settlers of Utah were African Americans Green Flake, Hark Lay, and Oscar Crosby. Two weeks after Mormon wagons rolled into the territory, Crosby was baptized in the church. When Flake returned to the East with Young, the other African Americans helped build the colony’s homes, prepared soil for planting, and constructed irrigation dams.

In early Salt Lake City, Black Mormons pitched in as farm laborers, house servants, carpenters, store clerks, midwives, and teamsters. Frontier hardships found people of both races sharing food and the small, crude, dirt homes they had dug into hills.

By 1850, twenty-six enslaved and twenty-four free African American Mormon men, women, and children lived in the Utah Territory. The church fathers agreed to set aside a building so they could develop their own activities and societies. Some formed an “African Band” to provide music and entertainment that would help ease the boredom and tediousness of desert life.

The Mormon migration to Utah included African Americans.

Despite the African American contributions to Mormon migrations and settlements, Young cited the Bible as a justification for slavery and said African people were condemned to be “servants of servants.” Though he personally was not an owner, Young said his colony could not prosper without enslaved workers and he welcomed slaveholders.

Slavery among the Mormons, however, granted many rights to the enslaved. African Americans lived in Young’s home, and others could take complaints directly to church elders. In 1851 the Mormon paper, the Millennial Star, reported that since no laws existed for or against slavery, anyone could leave. Its white editors also claimed that “All the slaves… appear to be perfectly contented and satisfied.”

The slavery that flourished in Oklahoma among the Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles began in the Southern colonies, their ancestral home. By the time the U.S. government drove these Five Nations to the Indian Territory during the Trail of Tears, slavery dominated their once-peaceful economic, political, and social life.

Although most Native American masters were not motivated by the profit-driven, mean-spirited bondage that marked Southern planters, issues of race bitterly divided the Five Nations and sparked class divisions and notions of superiority based on blood. And in 1842 dozens of enslaved Cherokees launched a rebellion that also gained support among Black Creeks and Choctaws. It took a hundred Cherokee militiamen to crush their drive for liberty.

In the 1850s the Oklahoma Indian Territory was ruled by proslavery federal Indian Agents and surrounded by Southern states. However, in interviews conducted during the 1930s, African Americans held by Native Americans testified they fared far better than their sisters and brothers in the South. They shared their owners’ resources, problems, and good times, they said, and were, in the words of one, “eating out of the same pot.”

These new disciples of civilization have learned from the whites to keep Negro slaves for house and field labour; but these slaves receive from the Indian masters more Christian treatment than among the Christian whites. The traveller may seek in vain for any other difference between master and servant than such as Nature has made in the physical characteristics of the races; and the Negro is regarded as a companion and helper, to whom thanks and kindness are due when he exerts himself for the welfare of the household.

M. H. Wright and G. H. Shirk, “Artist [Heinrich B.] Mullhausen in Oklahoma,” Journal of Negro History (1953)

In 1846 slavery was outlawed in Oregon, but banning it was one matter, stopping slaveholders was another. Masters, overseers, and slaves operated in plain sight, no one was arrested, and officials refused to act. Citizens, deeply divided over this issue, joined private militias that ominously marched, shouted, and drilled, but in Oregon no one seemed ready to fire a weapon or start a battle.

During Oregon’s first legislative session delegates introduced three bills to safeguard slave property. Masters needed legal protection, insisted legislator William Allen. “There are slaves here, but no laws to regulate or protect this kind of property.”

While masters defied the law, enslaved people mounted a resistance. In 1846 Robin and Polly Holmes began a long struggle to free their growing family from the grip of Nathaniel Ford, a Missouri sheriff who had promised to liberate them in Oregon. Each time they raised his promise, Ford threatened to drag them back to Missouri. In 1850 Ford finally agreed to liberate Robin, Polly, and their infant son, but still claimed ownership of their two other daughters and a son.

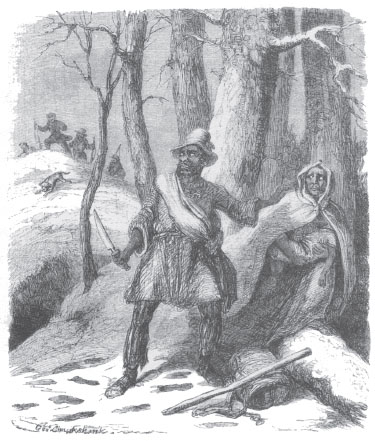

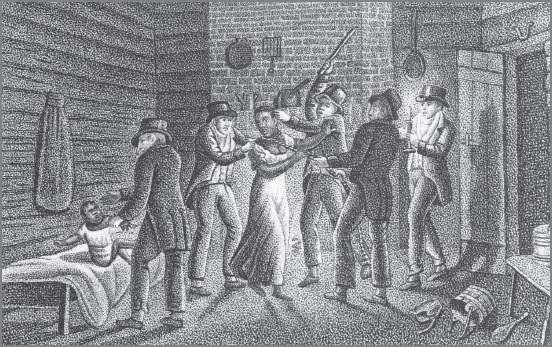

A slave couple prepares to fight bloodhounds and posses. (From an 1853 British publication)

When the anguished parents went to court for their children, Ford filed to keep the entire family, claiming Robin and Polly were too poor and ignorant to care for their children. An Oregon judge permitted Ford long delays and asked each side for a bond of $1,000, which the Holmeses did not have. Finally the Holmes family brought their plea before George H. Williams, the state’s new Supreme Court chief justice. He not only returned the children to their parents, but ruled slavery in Oregon was illegal “without some positive legislation establishing slavery here.”

The West was destined to become the first battleground of the Civil War. A host of abolitionists, such as John Brown, who first rose in the East, became antislavery leaders in Western territories. Agitators in New England could be ignored, but frontier citizens unwilling to cooperate with slaveholders spelled doom for the expansion of their system. Western men and women who aided escapees, confronted slave-hunting posses, and demanded local governments cease any surrender to Southern interests, made Western bondage costly and precarious.

Some frontier legislators boasted of their militant antislavery views and actions. Ohio representative Joshua Giddings told Congress how he defied the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 by aiding runaway slaves: “as many as nine fugitives din[ed] at one time in my house. I fed them, I clothed them, gave them money for their journey and sent them on their way rejoicing.” His two sons, he proudly noted, served as their guides. Giddings’s Senate colleague, Salmon P. Chase, provided aid to so many escapees that in Ohio courts he was known as “the attorney general of the fugitive slaves.” As punishment for their activities, Congress denied both Giddings and Chase appointments to key committees. When John Brown traveled east to raise funds among New England abolitionists, he carried a note of recommendation from the new Ohio governor, Salmon P. Chase.

President Buchanan faced a determined man in Chase. When a Mechanicsburg, Ohio, white man hid a slave in his home and fired on a slave-hunting posse, the federal government issued a warrant for his arrest. Governor Chase countered by securing a warrant for the arrest of the posse members. President Buchanan agreed Chase had checkmated him, and canceled the warrant.

The Western antislavery movement produced its share of antislavery societies. By 1837, Ohio’s 213 antislavery groups placed it second only to New York’s 274 and ahead of the 145 in Massachusetts.

Reverend Elijah Lovejoy, who had been driven out of St. Louis for publishing denunciations of bondage, brought his printing press to Alton, Illinois, and continued to issue fierce antislavery editorials. Twice at Alton, mobs attacked Lovejoy’s office and threw his press into the river. The third time in 1837, Lovejoy and his brother Owen waited with guns; but the mob killed Elijah and destroyed his press. Owen Lovejoy was later elected to Congress. During a meeting to commemorate Elijah Lovejoy’s martyrdom a young John Brown raised his hand and pledged to fight slavery to the death.

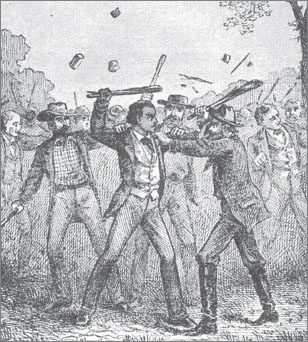

At our first meeting we were mobbed, and some of us had our good clothes spoiled by evil-smelling eggs. This was at Richmond… At Pendleton this mobocratic spirit was even more pronounced. It was found impossible to obtain a building in which to hold our convention, and our friends, Dr. Fussell and others, erected a platform in the woods, where quite a large audience attended. As soon as we began to speak a mob of about sixty of the roughest characters I ever looked upon ordered us, through its leaders, to be silent, threatening us, if we were not, with violence. We attempted to dissuade them, but they had not come to parley but to fight, and were well armed. They tore down the platform on which we stood, assaulted Mr. White and knocked out several of his teeth, dealt a heavy blow on William A. White, striking him on the back part of the head, badly cutting his scalp and felling him to the ground. Undertaking to fight my way through the crowd with a stick which I caught up in the melee, I attracted the fury of the mob, which laid me prostrate on the ground under a torrent of blows. Leaving me thus, with my right hand broken, and in a state of unconsciousness, the mobocrats hastily mounted their horses and rode to Andersonville, where most of them resided.

Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1892)

In 1837 a white mob in Alton, Illinois, attacked and killed Elijah Lovejoy for publishing an antislavery newspaper.

Frederick Douglass tries to fight off an Indiana mob.

In Ohio, housewife Harriet Beecher Stowe interviewed escapees who crossed the river from Kentucky, and used this material to write her worldwide best seller, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And a tall, gaunt former slave, Sojourner Truth, spent two years driving her horse-drawn buggy along the Ohio riverfront speaking to whoever would listen about their duty to help runaways who crossed the river. She supported herself by selling six hundred copies of her slave narrative.

Men and women who successfully escaped from bondage usually found they had to rely on themselves and free people of color. Most did not find the famous Underground Railroad but simply followed the North Star from their plantations and towns. Others took different paths. Some fled southward from Georgia and the Carolinas to Florida, from Texas to Mexico, from Virginia and North Carolina to the Great Dismal Swamp. Many found a refuge in Native American villages, or in Quaker or African American frontier communities, or in Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico.

In the Midwest an Underground Railroad began after the War of 1812 and moved passengers northeast from Ohio and Indiana to the shores of Lake Erie, and from Illinois and Iowa to the southern shore of Lake Michigan. Conductors found riverboat pilots who were willing to bring escapees to Canada. William Wells Brown, a runaway himself, piloted a boat that moved people from Detroit and Buffalo to Canada. “In the year 1842,” he wrote, “I conveyed from the first of May to the first of December, 69 fugitives over Lake Erie to Canada.”

Indiana stations were kept busy and on the defensive. From 1839 Reverend Chapman Harris, his wife, and their four sons, African Americans from Virginia, directed their rescue mission work from a cabin in Madison. Indiana and Kentucky residents across from each other on the Ohio river used bonfires to communicate. For refusing to reveal where he had hidden slaves in Indiana, African American Griffith Booth was beaten by a Madison mob, and on another occasion, thrown into the Ohio River. For aiding fugitives in Indiana, three African Americans were sentenced to the Kentucky state prison at Frankfort and one died there.

William Wells Brown

By the 1840s African Americans in Indiana had formed military units. In 1849 a Black militia and armed whites confronted a Kentucky slave-hunting posse, ordered it to leave, and watched the men gallop off.

In frontier Detroit, community resistance started early. In 1833 Thornton Blackburn and his wife, who had fled Kentucky to settle in Detroit, were jailed as runaways after a Kentucky posse complained to a judge. Black men packed the courtroom and others deployed near the jail armed with clubs and guns. Black women devised their own strategy. On Sunday a women’s delegation visited Mrs. Blackburn in her cell. After Mrs. George French secretly changed clothes with her, Mrs. Blackburn left with the delegation. On Monday Black men attacked the sheriff, fractured his skull, and freed Thornton Blackburn. By evening the Blackburns had been reunited in Canada.

Detroit’s mayor Marshall Chapin summoned a company of the U.S. Fourth Artillery Regiment to restore order. Thirty people were arrested for aiding the fugitives, but none was convicted.

By 1846 William Lambert and George DeBaptiste, both born free, successful businessmen and community leaders in Detroit, recruited and trained an “African-American Mysteries: the Order of the Men of Oppression.” Their first military operation was a daring daylight raid on a courtroom that seized fugitive Robert Cromwell and spirited him to Canada. “Our law point was bad,” Lambert conceded, “but we were many in numbers and resolute.”

To protect their society Lambert and DeBaptiste swore recruits to secrecy and devised tests for membership. “The general plan was freedom,” Lambert explained, and this included “arranged passwords and grips, and a ritual, but we were always suspicious of the white man, and so those we admitted we put to severe tests…” The African American society did admit two whites, a trustworthy local friend and abolitionist John Brown.

Fugitives were hidden near Lake Huron, Lambert recalled. “There they found food and warmth, and when, as frequently happened they were ragged and thinly clad, we gave them clothing. Our boats were concealed under the docks, and before daylight we would have everyone over [to Canada]. We never lost a man by capture at this point, so careful were we…” Slave catchers often were hot on their trail. “It was fight and run – danger at every turn,” Lambert remembered, “but that we calculated upon, and were prepared for.”

The Ohio branch of the Underground Railroad may have been the most active in the nation. Rutherford B. Hayes, who had served as an attorney for runaways, believed that during the months the Ohio River was frozen, so many people crossed the ice from Kentucky that stations suffered serious congestion.

Underground Railroad hero William Lambert

Reverend William Mitchell escaped to Ohio, where he and his wife devoted their lives to liberation. They would send posses who appeared at their door back for search warrants, and then whisk fugitives to safety before they returned. One Saturday Mitchell mobilized his friends among both races to help rescue a runaway. During a heated trial argument the courtroom became unruly and Mitchell’s allies whisked the man to safety. On Sunday, Mitchell brought the prisoner to church and collected enough money for him to reach Canada.

From 1843 to 1855 Mitchell’s life was dedicated to liberty: “Many are the times I have suffered in the cold, in beating rains pouring in torrents from the watery clouds, in the midst of the impetuosity of the whirlwinds and wild tornadoes, leading on my company, not to the field of sanguinary war and carnage, but to the glorious land of impartial freedom, where the bloody lash is not buried in the quivering flesh of the slaves.”

In 1860 in The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, pubished in England, Mitchell told his story. It was the first book to appear at a time when the Fugitive Slave Law required the arrest of all participants. His book celebrated his secret conductors as “patriotic men, white and colored, voluntarily going into the Slave States and bringing away their fellow men.” He told of John Mason, a fugitive himself, who “brought to my house, in 19 months, 265 human beings” whom “I had the privilege of forwarding to Canada.”

Ripley, Ohio, a mecca for former slaves and whites opposed to bondage, boasted at least one church “for repentant slaveholders” and became a leading station. In 1849 former slave John Parker, an iron worker, turned his house into a refuge for escapees and reported for the next dozen years he and his guests saw “adventurous nights together.” When Southern posses rode in, Ripley became a disputed territory. Parker recalled violent street brawls, shootouts, and times when “I never thought of going uptown without a pistol in my pocket, a knife in my belt, and a blackjack handy.”

Oberlin College and its town in northern Ohio acted as a junction of five different routes for the underground railroad. Founded in 1833, the college was the first to admit African Americans and women as students. One posseman called Oberlin an “old buzzard’s nest where the negroes who arrive over the underground railroad are regarded as dear children.” Students proved so successful in moving fugitives through town that four times the Ohio legislature tried to repeal the college’s charter. During a trial, a Southerner compared Painesville, Ohio, to Oberlin: “Went there and found a worse place than Oberlin. Never see so many niggers and abolitionists in any one place in my life! Dayton was with me. They give us 20 minutes to leave then wouldn’t allow us that! Might as well try to hunt the devil there as to hunt a nigger. Was glad to get away as fast as I could.”

A woman and her child are seized by slave catchers.

Wilbur Siebert’s famous 1898 study, The Underground Railroad, confirmed the daring record of Ohio’s Underground Railroad stations. It established that Ohio’s 1,540 runaway-aiding agents almost matched the total number, 1,670, active in the rest of the country. Siebert estimated that the total number of fugitives who entered Ohio from 1830 to 1860 was “not less than 40,000.”

For more than a century after his death in 1858, Dred Scott was the only person of color mentioned in school history books and social studies classes. He was pictured as an unlikely candidate for immortality – a confused man without normal roots or feelings, lazy, and stupid enough to become a pawn for white fanatics bent on disrupting the Union.

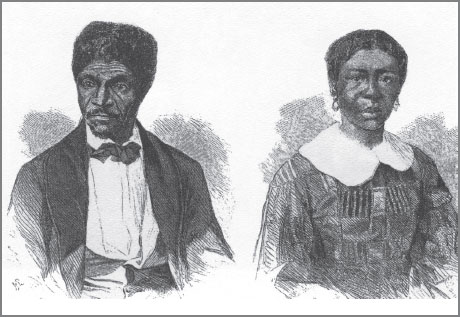

Dred Scott and Harriet Robinson met and were married at Fort Snelling. For eleven years they fought the U.S. legal system to win freedom for their two daughters and themselves.

Scott did not fit this image, and little mention was made of his devoted family. In 1836 he was taken by his owner to Minnesota, where the Northwest Ordinance, the Missouri Compromise, and the territorial laws barred bondage. At Fort Snelling he met Harriet Robinson, the slave of an Indian agent, and the couple were married in a civil ceremony.

Dred and Harriet Scott became members of the Second Baptist Church in St. Louis. They proved courageous and persistent in their quest for freedom. Once Dred Scott fled to the Lucas swamps near St. Louis, a haven for runaways, and was recaptured. Working at extra jobs, he saved $300, which in 1846 he offered his new owner as a down payment on his family’s freedom. It was rejected. Then Harriet and Dred Scott sued in court for their liberty and that of their two daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, and for $10 in damages for false imprisonment. In 1850 they won their case. Two years later the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the ruling, and they appealed. Abolitionists then assisted with legal and financial aid.

The Scotts were simply another family who wanted to be free. They had no idea their case would stoke the fires of the new Republican Party, advance the career of Abraham Lincoln, and help precipitate the country’s bloodiest war.

After a legal battle of ten years and ten months, a seven-to-two Supreme Court majority denied their plea in 1857. In a stunning ruling, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney declared the Missouri Compromise – and all congressional regulation of slavery in the territories – unconstitutional. He also stated that Black people even if free “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” President-elect James Buchanan, in secret violation of the Constitution’s separation of powers, secretly communicated to Justices Taney, Catron, Grier, and Wayne his desire for a proslavery ruling. His wish was granted, but the national reaction was so strong it eventually led to the Fourteenth Amendment.

After Taney had spoken, the Scotts were purchased and freed by white friends. They continued to live in St. Louis, Dred as a hotel porter who also assisted Harriet with her laundry business. Years of bondage, old age, and deteriorating health had taken their toll. Dred died the year of his liberation, Harriet, a year later.

In The Dictionary of American Biography, scholars Ray Allen Billington and Richard Bardolph have dismissed Dred Scott with the redundancy “shiftless” and “lazy.” Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Bruce Catton called Scott “a liability rather than an asset” to his owner. None mention a life of hard labor and dedication to family, church, and liberty. Dred Scott was hardly a stupid, lazy dupe.

Despite repeated failures, endless delays, and the collusion between a president and his Supreme Court, Dred Scott was able to gain his family’s freedom. School texts have labeled “heroic” those who have done far less. The Scott family never had their day in court. Scholars have tried to strip Dred Scott of his manhood and resistant spirit. This is a tragic comment on the way our American story has been distorted and whitewashed.