The Compromise of 1850 admitted California as a Free State but it also set the stage for a decade of civil strife. A resounding victory for proslavery forces, the law welcomed slavery into the huge land area taken from Mexico by war. It also provided a stringent new Fugitive Slave Law and sent posses led by U.S. marshals into Free States and mandated fines and prison for citizens who aided runaways or refused to assist in their capture.

After escaping, a hundred former slaves wrote or dictated their life stories as their part in the battle against human bondage.

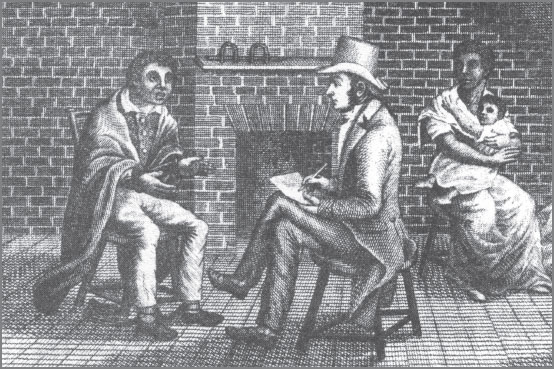

In this picture from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Eliza reveals she is going to flee in order to save her child from slavery.

The response was not what the white South had expected. Ohio’s Green Plain Quaker yearly meeting declared that its members would aid fugitives “in defiance of all the enactments of all the governments on earth… If it is really a constitutional obligation that all who live under the government shall be kidnappers and slave catchers for Southern tyrants, we go for revolution.” Eight states, including Michigan, Wisconsin, and Kansas, passed “Personal Liberty Laws” that allowed citizens to defy the law. Near Oberlin, Ohio, Lewis and Milton Clarke, themselves escapees, trained a Black militia to challenge “kidnapping” posses. Abolitionists in the North and West prepared for combat.

In Cincinnati, young Harriet Beecher Stowe learned about slavery as she helped fugitives escape across the Ohio River.

September 13, 1858, was “at once the darkest and the brightest day in the Calendar of Oberlin,” wrote Black Ohio attorney John Mercer Langston. Two dozen Black and white citizens of Oberlin and Wellington rescued fugitive John Price from three U.S. marshals. Langston, whose brother Charles was one of the two tried and convicted for the crime, wrote: “Names must not be mentioned. The conduct of particular individuals must not be described. It is enough for us to know, just now, that the brave men and women who came together in hot haste, but with well-defined intention, returned as the shades of night came on bringing silence and rest to the world, bearing in triumph to freedom the man who, but an hour before, was on the road to the fearful doom of slavery.”

“I was tried by a jury who were prejudiced; before a Court that was prejudiced; prosecuted by an officer who was prejudiced…

“One more word, sir, and I have done. I went to Wellington, knowing that colored men have no rights in the United States, which white men are bound to respect; that the Courts had so decided; that Congress has so enacted; that the people had so decreed.”

John M. Langston, Anglo-African Magazine, Vol. I (July 1859)

Attorney and later congressman, John Mercer Langston

The Compromise of 1850 ushered in a fearful time for free African Americans that undermined their efforts for equality. In 1853, the Washington Territory, with little more than a dozen African American families, limited voting rights to white men. California passed its own harsh Fugitive Slave Law. In 1860 Nebraska, New Mexico, and Utah, with only a dozen or so African American families in each territory, voted to deny Black pioneers any right to vote, hold office, or serve in the militia.

In 1848 Wisconsin joined the Union with several hundred African American families, and as the only state to enter without passing Black Laws. But in 1857, when Wisconsin’s 770,000 white residents elected a Republican governor, they turned down equal suffrage by 40,106 to 27,550.

At the 1850 Indiana Constitutional Convention, feverish outbursts marked debates about race. One delegate suggested that “it would be better to kill them [Black residents] off at once, if there is no other way to get rid of them…” He pointed to a precedent: “We know how the Puritans did with the Indians who were infinitely more magnanimous and less impudent than the colored race.” A proposed equal suffrage was voted down 122 to 1. Instead, the convention passed a provision denying entrance to emigrants of color; the Indiana electorate approved it by a vote of 113,628 to 21,873, or five to one.

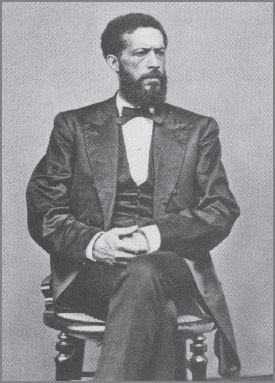

An abolitionist depiction of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

In 1855, as war raged over slavery in Kansas, antislavery delegates heard their Topeka convention president, James H. Lane, triumphantly predict “a decided majority” of voters “will favor” exclusion of African Americans. The African, Lane added, was a connecting link between man and the orangutan. In an election boycotted by proslavery forces, an exclusion provision passed three to one. A Free State man explained to a New York Tribune reporter: “First, then be not deceived in the character of the anti-Slavery feeling. Many who are known as Free-State men are not anti-Slavery in our Northern acceptation of the word. They are more properly negro haters, who vote Free-State to keep negroes out, free or slave; one half of them would go for Slavery if negroes were to be allowed here at all. The inherent sinfulness of slavery is not once thought of by them.”

This is a question of life and death to us in Oregon, and of money to this Government. The Negroes associate with the Indians and intermarry, and, if their free ingress is encouraged or allowed, there would a relationship spring up between them and the different tribes, and a mixed race would ensue inimical to the whites; and the Indians being led on by the Negro who is better acquainted with the customs, language, and manners of the whites, than the Indian, these savages would become much more formidible than they otherwise would, and long and bloody wars would be the fruits of the comingling of the races.

Congressman Samuel Thurston, Letter of the Delegate from Oregon to the Members of the House of Representatives, First Session, 31st Congress, in Oregon Historical Society Manuscript Collection

In Oregon, the idea of “popular sovereignty” prompted legislators to introduce three bills to safeguard slave property. “There are slaves here, but no laws to regulate or protect this kind of property,” lamented legislator William Allen. In 1857, Oregon’s constitutional convention voted to restrict people of color from the militia and the suffrage. Voters sanctioned the constitution by 4,000 votes, rejected slavery by 5,082 votes, and approved exclusion of African American migrants by an eight-to-one majority – in a land with only few dozen Black families. Oregon became the only state to enter the Union with a constitutional provision that denied admission to African American emigrants. The shadow of slavery had lengthened to the Pacific.

Free people of color in Texas had faced mounting hostility since the early days of the Lone Star Republic, when the Ashworth family of Jefferson County ran a successful ranch. Aaron Ashworth owned 2,570 cattle and Mrs. Ashworth owned land valued at $11,000. The family’s wealth and friendship with influential whites enabled them to defy certain racial laws. Then, in the 1850s, a Texas Vigilance Committee tried to drive the Ashworths away. New York Times reporter Frederick Law Olmsted told how the family armed 150 men, including whites and Spaniards, and prepared for a war. For weeks homes were burned, men assassinated, and anarchy and violence reigned. Men fired away in broad daylight and a sheriff and a deputy were among the slain. State militia units finally had to quell the disorder.

Slave discontent, another barometer of the rising tension in the 1850s, led to more patrols and stronger Slave Codes and Black Laws. But white Texans still spent many sleepless nights.

The arguments over Kansas, “popular sovereignty,” and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision intensified sectional strife. In 1860, Sylvester Gray, who had homesteaded a 160-acre farm in Wisconsin since 1856, was informed by a U.S. land commissioner that his homestead was revoked because he was “a man of color.”

The next year, when Mrs. Mary Randolph was put off a Colorado-bound stagecoach because of her color, it was hard to determine whether it was a result of the Dred Scott decision or narrow-minded attitudes. All Mrs. Randolph knew was that she was left behind as the stagecoach rolled on to Denver, and had to spend a lonely night on the Kansas plains snapping her umbrella open and shut to frighten away coyotes.

Though the Republican Party was pledged to halting slavery in the West, it loudly committed itself to a white country. Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois said: “We, the Republican Party, are the white man’s party. We are for the free white man, and for making white labor acceptable and honorable, which it can never be when negro slave labor is brought into competition with it.” Abraham Lincoln emphasized that Republicans want the territories “for homes of free white people.”

Fugitive Henry Bibb edited a Canadian paper, Voice of the Fugitive, that called on his people to flee to Canada.

During the 1850s Black emigrationist sentiment soared in the East and West, and thousands of free people of color sought refuge in Canada, some in Mexico. In August 1954 a Black emigration convention drew 102 enthusiastic delegates, including 29 women, to Cleveland, Ohio, with a president from Michigan, the first vice president from Indiana, and the second vice president, Mrs. Mary E. Bibb, from the Midwest. Mrs. Bibb had moved to Canada with her husband, Henry Bibb, where they had started Voice of the Fugitive, a paper advocating a Black exodus from the United States. Delegates denounced “our white American oppressors,” “refused submission” to the Fugitive Slave Law, and scorned attempts to open new land to slavery as “contemptible.”

I can hate this Government without being disloyal because it has stricken down my manhood, and treated me as a saleable commodity. I can join a foreign enemy and fight against it, without being a traitor, because it treats me as an ALIEN and a STRANGER, and I am free to avow that should such a contingency arise I should not hesitate to take any advantage in order to procure such indemnity for the future.

H. Ford Douglass, Proceedings of the National Emigration Convention of Colored People (1854)

Still other African Americans responded to the turmoil of the 1850s by heading westward. The number of free people of color in the West had increased sharply, according to the 1860 U.S. Census: 36,673 in Ohio, 11,428 in Indiana, 7,628 in Illinois, 6,799 in Michigan, 1,171 in Wisconsin, 1,069 in Iowa, 259 in Minnesota, 128 in Oregon, 82 in Nebraska, 46 in Colorado, 59 in Utah, 45 in Nevada, 30 in Washington, 85 in New Mexico, and unrecorded but smaller numbers in Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas. The Census also found increased numbers of free people of color in Western slave states: 355 in Texas, 3,572 in Missouri, 7,300 in Tennessee, and 10,684 in Kentucky (Bureau of the Census, Negro Population 1790–1915. [Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918], p. 44).

In 1863 Rev. Robert Hickman organized a massive slave flight from Missouri to St. Paul.

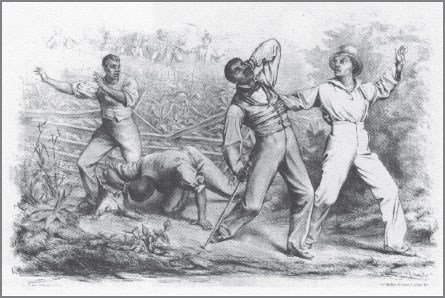

Proslavery Missouri raiders cross into Kansas in 1856.

For those who hoped sectional differences could be resolved through further compromises, the 1850s had a terrifying answer. Senator Stephen A. Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act offered his “popular sovereignty” solution to the issue of slavery in the West. Popular sovereignty, he believed, would turn an inflammatory national issue into a peaceful local vote. He also hoped that his device of letting residents of a territory decide the issue would land him in the White House.

The new law, however, nullified the Missouri Compromise, opened all of the West to slavery, and created new conflicts. In Kansas popular sovereignty ignited a miniature civil war. Grumbling farmers along the upper Mississippi Valley, determined to close Western lands to slaveholders, formed the Republican Party to oppose any extension of slavery to the West.

I was required to mount a box in front of the store, and, then the auction began. “How much am I offered for this black boy,” the auctioneer cried. “See, he is a fine boy, he is about twenty years old, we guarantee his health, he is strong, and he will give you years of service. Step right up and feel his muscles and look at his teeth. You will see that he is a fine specimen of young manhood.”

The first bid was $100 and the auctioneer kept asking for other bids, first 25, then 10 and even $5 until they ran the bids up to $200. Then, as he could get no other bids, he sold me for $200. While the auction was going on I noticed a group of twenty-five or thirty men armed with clubs and riding horses hurrying down the ravine. I noticed one of the men was leading a saddled horse without a rider; the two crowds came together with a clash and there was much brawling and cursing. There were many bloody noses, and some heads cracked by the clubs. It was a bunch of “free soilers” who were determined to break up the auction. The man leading the riderless horse rushed up to me and shouted, “The moment your feet touched Kansas soil, you were a free man,” and, then, he ordered me to mount the horse and we rode at a fast gallop, leaving the two groups of men to fight it out.

Uncle Mose, quoted in Negro History Bulletin (March 1955)

In Kansas both sides prepared for war. A New England Emigrant Aid Society began to ship rifles to Kansas Free-Staters and pledged to send twenty thousand settlers before the year was out. On election day of 1855, five thousand heavily armed Missouri “Border Ruffians” rode in, seized voting booths and cast four times as many ballots as there were legal voters. Missouri posses killed six Free-Staters and no one was arrested. The next year eight hundred “deputized” Missourians attacked and burned the Free State capitol at Lawrence, and destroyed two newspapers.

John Brown and his raiders arrived too late to save the city, but three days later they calmly executed five proslavery men by sword. Scholars have recoiled in horror at this cold-blooded act, but Free-Staters welcomed the retaliation, and Brown’s name became a rallying cry. When 150 Missourians attacked and burned Brown’s camp at Osawatomie, Brown told his son Jason what he saw in the flames: “God sees it. I have only a short time to live – only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause. There will be no more peace in this land until slavery is done for. I will give them something else to do than to extend slave territory. I will carry the war into Africa.” This pledge would lead Brown to Harpers Ferry and martyrdom.

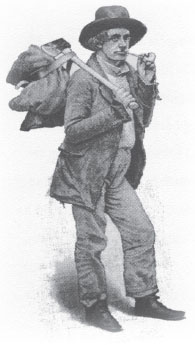

Kansas governor Andrew Reeder dressed as a peddler to escape capture by proslavery militia.

As guerilla warfare raged in Kansas, President Franklin Pierce and his secretary of war, Jefferson Davis, declared the Free State movement a rebellion. When Governor Andrew H. Reeder protested the Missourians’ wanton disregard for elections, he had to flee Kansas disguised as a peddler. A newly elected proslavery Kansas government rammed through laws that limited free speech, press, and officeholding to men who favored slavery. At one point two governors ruled Kansas.

On Christmas night, 1858, John Brown’s Kansas band freed eleven Missouri men and women, concealed the women on a frontier farm and the men in shacks used for corn, and then guided the party to Canada.

On Sunday, December 19 [1858], a negro man called Jim came over the river to Osage settlement, from Missouri, and stated that he, together with his wife, two children, and another negro man, was to be sold within a day or two, and begged for help to get away. On Monday (the following) night, two small companies were made up to go to Missouri, and forcibly liberate the five slaves, together with other slaves. One of these companies I assumed to direct. We proceeded to the place, surrounded the building, liberated the slaves, and also took certain property supposed to belong to the estate. We, however, learned before leaving that a portion of the articles we had taken belonged to a man living on the plantation as a tenant, and who was supposed to have no interest in the estate. We promptly returned to him all we had taken. We then went to another plantation, where we found five more slaves, took some property and two white men. We moved all slowly away into the Territory for some distance, and then sent the white men back, telling them to follow us as soon as they chose to do so. The other company freed one female slave, took some property, and as I am informed, killed one white man (the master), who fought against the liberation.

John Brown, letter from Trading Post, Kansas, January 1859

In 1859, six months before Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, underground agents in Lawrence, Kansas, were in dire need of help. So many fugitives had crowded its stations, wrote Colonel J. Bowles to Franklin B. Sanborn that April, that only massive financial aid could end congestion. In the last four years, Colonel Bowles wrote, “nearly three hundred fugitives” passed through Lawrence. In 1860 the number of African Americans in Kansas rose to sixty-two, and during the Civil War it swelled to more than twelve thousand, almost a tenth of the total population.

For his raid on Harpers Ferry, John Brown had raised money and recruits in the East and West. His band of seventeen whites and five Blacks included John Copeland and Lewis Sheridan Leary, an ancestor of Langston Hughes, both from Oberlin, and five of his own sons. Brown’s plan failed. He was convicted of treason and hanged as John Wilkes Booth, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson looked on. In eighteen months these witnesses and others helped form the Confederacy and initiate the Civil War. Not long after that, Union soliders marched into battle singing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” with new lyrics about John Brown – “His truth goes marching on.” By the war’s end U.S. soldiers would complete the bloody work begun at Harpers Ferry.

Lewis Sheridan Leary fought and died during John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

The murder and turmoil in Kansas swelled the ranks of the Republican Party and dashed the hopes of Senator Douglas. In 1856 John C. Frémont, the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, carried all states but five north of the Mason and Dixon line, unifying Northerners and Westerners as never before. In 1858 a political unknown, Abraham Lincoln, almost toppled Douglas from his Illinois Senate seat. Only an antiquated electoral system saved Douglas from defeat. When Douglas became the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate in 1860, his party’s Southern wing split off to back another candidate, ensuring the election of Lincoln.

Planters knew they faced a choice between growth and death, since their plantation system had ruined the South’s soil. Less than two generations after Mississippi entered the Union, a soil expert reported that “a large part of the state is already exhausted; the state is full of deserted fields.” Judge Warner of Georgia told the U.S. Congress, “There is not a slaveholder in this House or out of it, but who knows perfectly well that whenever slavery is confined within certain specified limits, its future existence is doomed.”

The Southern plantation system handed the reins of state power to a slaveholding elite. It also undermined the chances of hard-working and skilled whites. “Slavery drives free laborers – farmers, mechanics, and all, and some of the best of them too, – out of the country and fills their places with Negroes,” said the president of Virginia College. Southern roads were clogged with unemployed farmers and skilled mechanics, driven into exile, heading to the frontier. Wrote an Alabama politician: “Our small planters, after taking the cream off their lands, unable to restore them with rest, manures or otherwise, are going further west and south, in search of other virgin lands, which they may and will despoil and impoverish in like manner.”

By the 1840s leading planters advocated foreign expansion as the answer for the slave system. In April 1844, Secretary of State John C. Calhoun told a British diplomat he believed the annexation of Texas was necessary to protect slavery. As U.S. officials conspired to seize Texas, Texas’s president, Anson James, charged the U.S. with “unholy” attempts at “manufacturing a war with Mexico.” Mexican officials repeatedly warned that admitting Texas to the Union would be an act of war. But planters deemed Texas crucial to their economic and political power. In 1845 the United States admitted Texas and war broke out with Mexico. A young officer in the war, Ulysses S. Grant, later wrote: “I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral courage enough to resign… Texas had no claim beyond the Nueces River, and yet we pushed on to the Rio Grande and crossed it.”

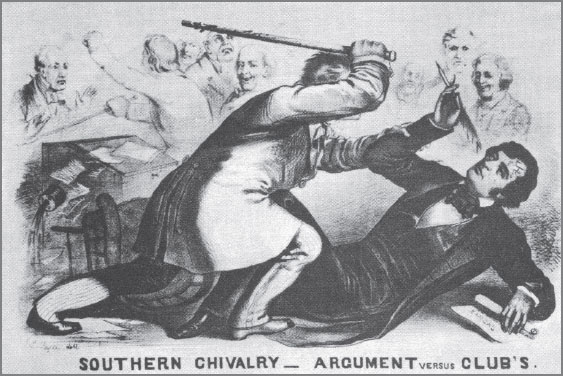

After Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts denounced Southern raids on Kansas, Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina beat him to the Senate floor.

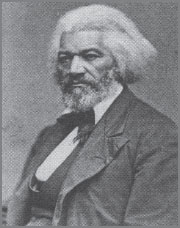

Frederick Douglass opposed any U.S. invasion or expansion that would bring slavery to other lands.

Let it be known, throughout the country, that one thousand Colored families, provided with all the needful implements of pioneers, and backed up by the moral influence of the Northern people, have taken up their abode in Kansas, and slaveholders, who are now bent upon blasting that fair land with Slavery, would shunt it, as if it were infested with famine, pestilence, and earthquakes. They would stand as a wall of living fire to guard it. The true antidote, in that Territory, for black slaves, is an enlightened body of black freemen – and to that Territory should such freemen go.

To the question, Can this thing be accomplished? we answer – Yes! Three cities can, at once, be named, in which, if proper means be adopted, nine hundred of the one thousand families can be obtained in three months, who would take up their abode as permanent settlers in Kansas the coming spring. New York City and its vicinity could send three hundred families. Philadelphia and its vicinity would gladly spare three hundred families more. Cincinnati and vicinity could afford three hundred families for such a purpose; and Boston, with the aid of New England, could easily send the additional one hundred – making an army of One Thousand families… The line of argument which establishes the right of the South to settle their black slaves in Kansas, is equally good for the North in establishing the right to settle black freemen in Kansas.

Frederick Douglass’s Paper, September 15, 1854

The invasion of Mexico stirred the conscience of freshman Congressman Abraham Lincoln; he challenged President Polk to justify his war by showing where American blood was shed on American soil. Philosopher Henry David Thoreau chose prison rather than pay taxes to support the war. “Abandon [your] murderous plans, and forsake the way of blood,” Frederick Douglass told U.S. officials, and called for “the recall of our forces.” Congressman Horace Mann said the war had a “twofold purpose of robbing that republic of its territory, and then robbing that territory of its freedom.”

In the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico surrendered half of its national domain and opened an area from Texas to California for slaveholder expansion. Congress repeatedly defeated a Wilmot Proviso that sought to prohibit slavery in the new lands. Planters enjoyed support in the North. Secretary of State James Buchanan of Pennsylvania and Northern Democrats wanted to annex all Mexico for slavery.

Slaveholders adopted the jingoist cry “Manifest Destiny” and announced that their goal was “to overspread the continent allotted by Providence.” In 1842 Virginia Congressman Henry A. Wise, an administration spokesman in the House, declared, “slavery should pour itself abroad without restraint, and find no limit but the Southern ocean.” In 1854 the U.S. ambassadors to Britain, France, and Spain met in Ostend, Belgium, and issued a declaration that if Spain did not sell Cuba to America “by every law human and divine, we shall be justified in wresting it from Spain if we possess the power.”

Voices of Southern imperialism became more unrestrained. Mississippi Governor John Quitman, under indictment for aiding an 1850 invasion of Cuba, resigned his post to visit Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia to drum up support for another foreign adventure. Senator Sam Houston of Texas urged the United States to seize Mexico and use it as a base to impose slavery and domination on South America.

Words soon led to action for William Walker, a Tennessee doctor and career militarist who planned “filibustering” expeditions to extend the slaveholders’ empire. He tried to seize Lower California and Sonoma from Mexico to launch incursions into Central America. In 1855 Walker captured Nicaragua, declared himself dictator, restored slavery, and had his diplomats received by President Pierce. Walker also proclaimed “a formal alliance with the seceding states.” But Central American forces united against Walker, and by 1857 his invasion had collapsed.

In 1860 Walker invaded Central America, but the British Navy intercepted him and turned him over to Honduran officials. Three months before eleven Southern states seceded from the Union, a firing squad representing the three races of the Americas ended Walker’s violent life.

Slaveholders’ rapacity did not retreat. In 1858 Mississippi governor Albert Gallatin Brown announced: “I want Cuba, I want Tamaulipas, Potosi, and one or two other Mexican states; and I want them all for the same reason – for the planting and spreading of slavery.” For such men, secession and war would be the only answer.