The Civil War has been called the Second American Revolution. It emancipated four million slaves. It enacted three constitutional amendments granting Black people citizenship and Black men the right to vote. But these lofty goals were policy changes forced on President Abraham Lincoln. For two years he fought to defeat the Confederacy, restore seceded states to the Union, and not “free a single slave.” It was a stalemate. When Congress passed the Corwin Amendment to extend slavery into the future, the president promised his support.

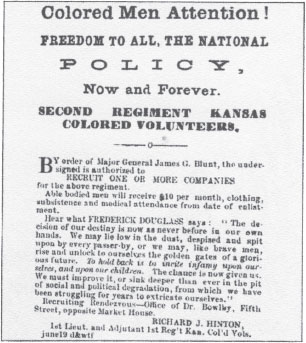

Abolitionist Richard J. Hinton, commander of the First Black Kansas regiment, used this poster to recruit a Second Regiment of Black Kansas Volunteers.

Both the Union and Confederate governments were as fiercely committed to white supremacy as any slaveholder. Like the earlier battles in “Bloody Kansas,” this war was about the new Western territories: Would they enter the union as free or slave states? Lincoln and the Republican Party pledged to save Western lands for white pioneer families.

By early 1861 betrayal was in the air, as thirteen slave states formed a confederacy, wrote a constitution, and chose a congress and president. Seceded states seized federal forts and property as they left. Treason even reached New York City, where Mayor Fernando Wood urged his city council to unite Manhattan, Long Island, and Staten Island as the Free State of “Tri-Insula” and join the Confederacy.

White supremacy guided Union war policies. When free Black men in the North and West rushed to enlist in the Union army, recruiters told them, “This is a white man’s war!” When enslaved families fled to Union lines seeking freedom (and offering to help), they were handed back to their Confederate owners. Union generals Butler and McClellan promised to crush slave revolts in their sectors, and Washington nodded in approval.

Commanding an army of 13,000 men and officers, and anticipating a brief conflict, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to serve for three months, the time he thought it would take to crush the rebellion. He was among 31 million other Americans who never expected a four-year carnage that would take 750,000 lives and leave no family untouched.

I was a student at Wilberforce University, in Ohio, when the tocsin of war was sounded, when Fort Sumter was fired upon, and I never shall forget the thrill that ran through my soul when I thought of the coming consequences of that shot. There were one hundred and fifteen of us, students at that university, who, anxious to vindicate the stars and stripes, made up a company, and offered our services to the governor of Ohio; and, sir, we were told that this was a white man’s war and that the negro had nothing to do with it. Sir, we returned -- docile, patient, waiting, casting our eyes to the heavens whence help always comes. We knew that there would come a period in the history of this nation when our strong black arms would be needed.

Congressman Richard H. Cain, Congressional Record, 43rd Congress, First Session

Frederick Douglass and his fellow abolitionists denounced Union policy for inviting defeat and encouraging treachery. He called for a “people’s revolution” – arm the enslaved and overthrow the slaveholder system. Lincoln and the vast majority of Americans considered abolitionists unrealistic fanatics.

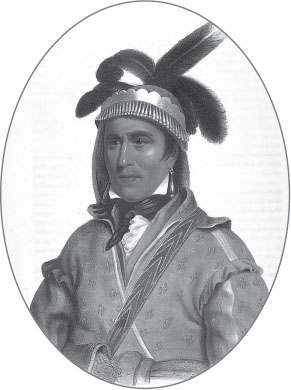

Creek Chief Opothleyahola decided to free his slaves and offer refuge to all neutrals in Oklahoma.

But during the fateful spring and summer of 1861, a people’s revolution began to explode in Oklahoma that shook the Trans-Mississippi West. It first stirred when U.S. troops were recalled from the Indian Territory to fight back East. Oklahoma’s Native American Nations, surrounded on three sides by slaveholding states, were now unprotected by the Union treaties. Confederates sent their diplomat Albert Pike in with troops. He forced Confederate treaties on Native American leaders as his soldiers arrested men for work details or as conscripts for their army. As Native American leaders caved in, they, African Americans, and whites alike tried to flee to safety.

Few Oklahomans, it was soon clear, wanted any part of a war to defend slavery. Leading the resistance were the Keetoowah, or PINS, a secret antislavery network of Indians and African Americans within Native American Nations. Opothleyahola, a wealthy Creek chief, also called “Old Gouge,” favored neutrality and opened his 2,000-acre North Fork stock-raising and grain plantation for people fleeing Confederate control.

Opothleyahola had fought U.S. slaveholder armies in two Seminole wars. He became an inspired voice defending his people’s traditional values. As ten thousand people of all colors raced to North Fork, he freed his slaves. With one in seven residents of Oklahoma in his plantation, it looked a refugee camp and sounded like a community meeting.

When Confederate colonel Douglas Cooper marched on North Fork with fourteen hundred troops, Opothleyahola’s neutrals began an exodus. Their plan was to circle northern Oklahoma recruiting more neutrals. Their enemies had other plans.

Cooper’s army dogged their trail. At Round Mountain on November 19, 1861, neutrals used bows and arrows and their few rifles to drive the enemy back to Fort Gibson. On December 7, while their officers were away, a large force of conscripted Indian Confederates visited Opothleyahola’s camp. What began with warm greetings ended the next morning with most Native American conscripts leaving for home and some joining the marchers.

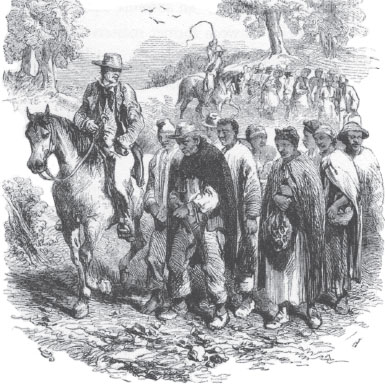

During the Civil War, slaveholders drove their captives into Texas, away from advancing Union armies.

On October 29, 1862, a clash at Island Mound, Missouri, became the first Civil War battle for African Americans.

Then a savage winter of wind and snow, one of the worst in years, swept in. At Chustenahlah on the day after Christmas Confederate troops opened fire on the march. Hundreds were slain. Cattle, ponies, and sheep died and survivors fled, leaving their food, supplies, wounded, and dead in the snow. One Seminole chief recalled: “At that battle we lost everything we possessed: everything to take care of our women and children with, and all that we had.”

As the neutrals headed toward Union lines in Kansas, their flight became “The Trail of Blood on Ice.” In early 1862 about 7,600 ragged, wounded, and traumatized people straggled into southern Kansas. It had few relief facilities, with only small tents for shelter and the cold, hard ground as a bed.

Devastating losses changed many young survivors who now wanted to fight to liberate slaves. Runaways from Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee also began fleeing to freedom in Kansas. By 1865 the state’s Black population had swelled to 12,527.

This multicultural force found Kansas stocked with abolitionist officers who had arrived in the 1850s with John Brown. The white officers embraced these men of Native American and African ancestry as the freedom fighters that Brown had always wanted to lead against slaveholders.

“…We need the services of such a man out there [in Kansas] at once – that we better appoint him a brigadier-general of volunteers today, and send him off with such authority to raise a force… [and] get him into actual work quickest.”

President Abraham Lincoln, June 1861

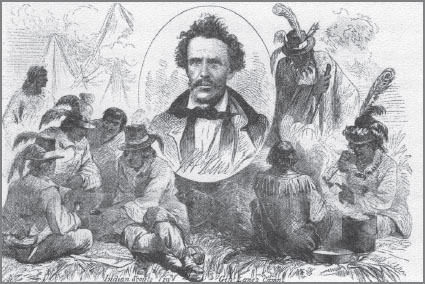

General James Lane (center) Lincoln’s choice for commander of Kansas Recruiting, recruited, trained, and led Black and Indian soldiers on raids into Missouri.

Their commander was General James Lane, the same committed racist who served as Topeka convention president in 1855. He was an Iowa general during the Mexican invasion that claimed a huge portion of Mexico for U.S. slaveholders. By 1856 Lane rode in “Bleeding Kansas” with Brown’s antislavery raiders to make Kansas a free state. Lane was later appointed one of its two U.S. senators.

In Washington in 1861, President-elect Lincoln met Lane as he prepared for his inauguration amid rumors of assassination plots. Lane offered to recruit 116 armed Kansans for the White House. For twenty days his men camped in the East Room while Lane slept outside the president’s bedroom. Lincoln eventually named him commander of Kansas recruiting.

General James Blunt, a doctor, became John Brown’s leading officer in Bleeding, Kansas. During the Civil War, he was an aggressive major general.

Grim-faced, impulsive, a man anchored only by his ambition, Lane followed a ruthless fighting code that his men admired and many others feared. He won the support of his officers and men as he built a freedom-fighting army of many races.

By the summer of 1861 Lane led the First Regiment Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, which included the first ex-slaves to fight in the war, into Missouri. His 30 men defeated 130 mounted Confederate guerrillas. He called his men “the finest specimens of manhood I have ever gazed upon.”

Lane authorized General Blunt, a doctor and Brown’s highest-ranking officer, to recruit more African Americans. By fall Blunt and other officers were leading troops of color eager to free Missouri slaves. To recruit runaways for his armies, Lane offered certificates of freedom and threatened those reluctant to take up arms.

By July 1862 Lane authorized Blunt to recruit all men in Kansas “willing to fight.” He picked two other officers he met in the 1850s: Colonel William Phillips, one of Brown’s two brigade commanders, and Captain Richard J. Hinton, Brown’s biographer. They trained and led invasions of slave territories. Kansas’s officers were now defying policies set by President Lincoln’s War Department. As soldiers rolled up victories, the War Department did not appear to notice.

After each invasion Lane guided or pushed some into his Kansas ranks. They were joined by runaways fleeing slave states, free men of color, and Native Americans. The appearance of Black soldiers inspired many escape plots and disrupted plantation life.

Kansas monument to its African American soldiers who fought for freedom

Kansas monument to John Brown

Between 1860 and 1863 Missouri’s enslaved population fell from 114,000 to 78,000. Runaways began to find refuge in Iowa, Illinois, and Kansas. To avoid the advancing Black troops, planters force-marched enslaved families as far away as Texas.

In such units as the Indian Home Guards and Indian Brigades, Black Indian members served as interpreters between their Native American brothers and white officers. The new troops continued to defeat or hold their own against seasoned Confederate units.

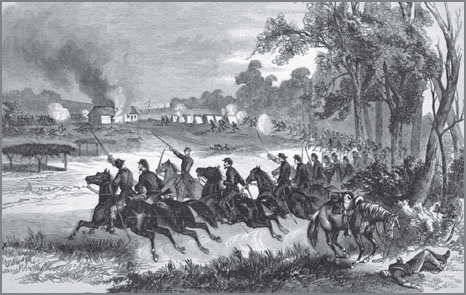

On July 17, 1863, Blunt’s multicultural army of 3,000 faced 6,000 Missouri State Guard, Confederate cavalry, and guerilla units at Honey Springs in the largest battle of the Indian Territory. Confident that the mere appearance of armed Confederates would cause Black soldiers to surrender, some Confederate soldiers arrived with 300–400 pairs of handcuffs. Instead the new Union soldiers routed the enemy in what the New York Times headlined their “desperate bravery.”

A U.S. officer reported, “They fought like tigers.” Six Killer, a Black Cherokee, shot two Confederates, bayoneted another, and clubbed a fourth with his rifle butt. Sergeant Edward Lowry, ordered to surrender by three Confederates, instead knocked all three from their horses.

From other trans-Mississippi battlefields, Union generals and Northern journalists reported the “extraordinary courage under fire” of the new troops of color. Clearly these soldiers were fighting for something more fiercely personal than saving the Union.

So too were Lane and his white officers. They repeatedly petitioned the War Department to pay their men the $13 a month granted to whites, and urged their best soldiers be appointed officers. Colonel James Montgomery’s “colored brigade” – Indians, whites and ex-slaves – fought for nine months without any wages to protest unequal pay. But equal pay came only after Emancipation and formal recruitment.

On Emancipation Day, January 1, 1863, Lane’s men and officers held their own celebration of the Union’s new policy. In a richly symbolic ceremony, Lane’s multicultural army honored their victories and saluted their hero, John Brown. Wives and children cheered their courage and the rescue of enslaved families. Blunt’s men sang the John Brown song, and added a final line – “John Brown sowed, and the harvesters are we.” Men and officers, Blunt wrote, then shared a barbecue and “strong drink.”

The decisive victory of the multicultural Kansas forces at Honey Springs in 1863 secured Union control of the Indian Territory.

John M. Langston of Ohio (center) recruited Blacks as soldiers. In 1863 he presented the regimental colors to the Fifth Infantry Regiment of the United States Colored Troops at Camp Delaware.

Lincoln’s mass recruitment of former slaves and free men of color arrived as both sides were running out of reserves. Enslaved families that had provided food for Southern citizens and soldiers, or picked cotton to sell abroad, became runaways. Confederate desertions rose and Southern cities faced food riots.

Emancipation also brought Frederick Douglass and the abolitionists to the fore as Union recruiters. Almost 200,000 Black men served in 150 regiments. With less training and fewer medical officers and facilities, recruits of color suffered 37,000 battlefield deaths. Runaways also served as spies, and others, including women, labored in Union Army camps.

The military success of Kansas soldiers of color “mostly from Missouri,” historian James M. McPherson notes in a letter to the author, was one of the “factors in the summer and fall of 1862 that moved Lincoln” toward issuing the Emancipation Proclamation.

These runaways and free men of color, when joined by more than 150,000 others, tipped the war’s balance. African American troops liberated Petersburg, Wilmington, Charleston (the heart of the Confederacy), and finally Richmond, its capitol. To cheering crowds of liberated slaves, Black Union cavalrymen escorted President Lincoln through the streets of Richmond.

Without his Black soldiers, the president said, he would have been forced to withdraw from the war in three weeks. In November of 1864, their success in battle helped persuade voters to elect him president for a second term. By then General Howell Cobb, whose Confederacy did not dare arm its slaves, wrote, “If slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

In 1862 Lane appointed African American William D. Matthews to artillery officer. Mathews’s life of daring had begun in running a Maryland station of the Underground Railroad. In Kansas he rode with John Brown and ran the busy Waverly House station. In January 1863, the Union formally commissioned him as a captain and its first official Black officer. In July 1864 Lane made officers of African Americans Patrick Minor and H. Ford Douglass. In Illinois, July 1862, Douglass became the only Black man to raise and command his own company. Minor had served as a recruiter.

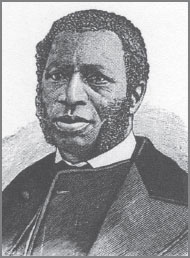

William D. Mathews, born a slave, ran an Underground Railroad station and then recruited and became a lieutenant of the First Kansas Colored Volunteers.

The three Black men began to assert their new authority and investigative powers to probe the treatment of soldiers of color. Commander Lane, they found, often forced enlistments with threats, or ordered former slaves beaten and starved. On August 3, 1862, he publicly threatened a thousand Black men to join the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment, saying, “If you won’t fight we will make you.” They exposed and ended this Lane practice.

Next the three found that their commander jailed Black soldiers too traumatized to fight for “shirking official duty,” whereas white soldiers suffering similar mental problems were discharged to their families. Matthews, Minor, and Douglass won Black men the right to return home.

In 1865 peace saw Commander Lane returning to his white supremacist roots. Kansas legislators again chose him as their senator. The next year Lane fired one more shot, taking his own life. Fellow Kansans named Lane University in his honor.

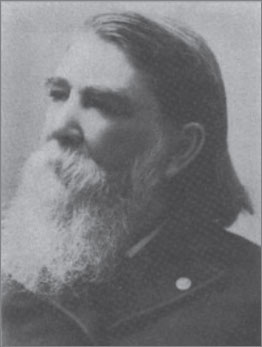

Richard J. Hinton fought in Kansas with John Brown and commanded Kansas troops of color during the Civil War.

Matthews, Minor, and Douglass settled into Kansas African American society. With Richard Hinton they organized the first Kansas Colored Convention to promote equal education and citizenship. Its delegates announced to white Kansas, “Our misery is not necessary to your happiness.” Kansas became the first state to erect monuments to John Brown and soldiers of color.

The Union armies of the Trans-Mississippi West blazed a historic trail. They were the first to enroll men of every race, the first to appoint officers of color, and the first to enter the Civil War as liberators.