Africans skilled with horses were among the earliest to ride alongside the New World’s cattle herds. In 1598 when Juan de Oñate’s expedition imposed Spanish rule on New Mexico, at least five African Americans, two soldiers and three enslaved women, accompanied him. Others, riding in cattle crews from the Mexican highlands, drove the cows and horses of mixed African, European, and American breeds that would ensure that European settlements survived.

Through an outdoor mix of talent, stamina, and sweat, Africans, Europeans, and Native Mexicans created the Southwest’s cattle industry. These men were first known by the Spanish word vaqueros, then the English word “drovers,” and finally as “cowhands.” Some authorities believe the word “cowboy” derives from the fact that so many were African Americans – and whites would not dignify them with the term “men.” Historically the language of trail and ranch was Mexican Spanish, using such terms as lariat, morral (feed bag), bosal (rope), and rodeo. The sombrero galoneado became the famous “ten-gallon hat.”

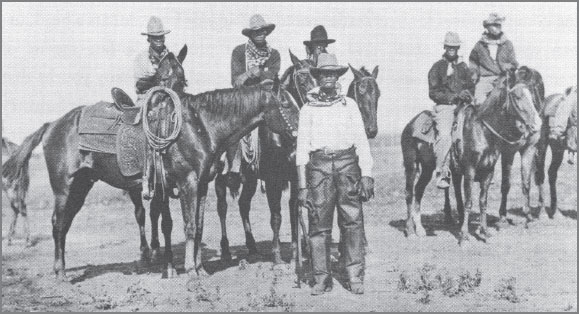

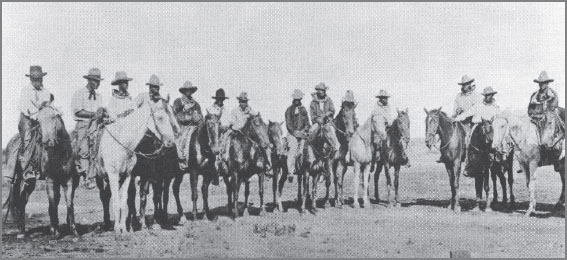

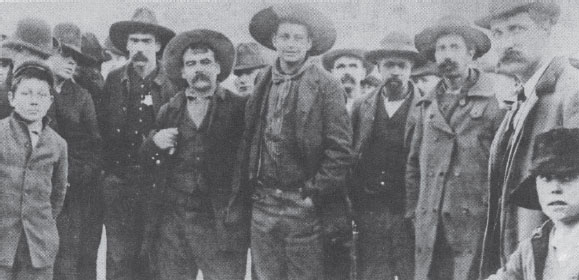

Cowhands assemble around 1910 for a Bonham, Texas, fair.

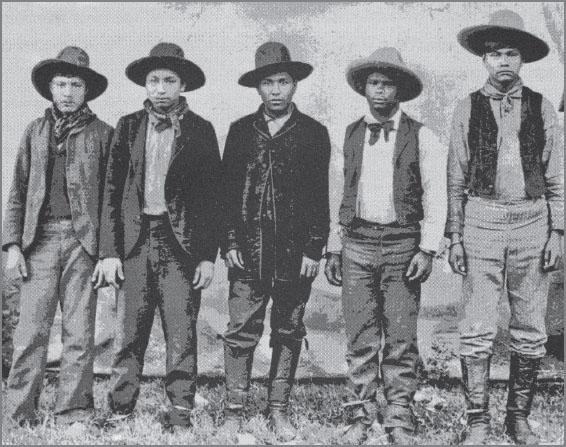

Shoshone Indians and their friend One Horse Charley (second from left) in Reno, Nevada (1886)

The great era of the cattle crews began after the Civil War in Texas, where five million cattle roamed free and ready for coralling. In an expanding country, prices for beef cattle soared to $30 or $40 dollars a head, urban markets beckoned, and new railroads provided a fast means of transportation. So many cowpuncher jobs opened to so many youths that rarely was race an issue in hiring. For African Americans the cattle industry offered one of the few chances for equal, exciting, manly labor in a country that increasingly closed other doors to people of color.

In 1866 Bose Ikard, born a slave in 1847, rode with Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving when they charted the Goodnight-Loving Trail to New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana. At nineteen Ikard had valuable riding, roping, and shooting skills and Goodnight called him “the most skilled and trustworthy man I had.” He continued: “There was a dignity, a cleanliness, and a reliability about him that was wonderful. He paid no attention to women. His behavior was very good in a fight, and he was probably the most devoted man to me that I ever had. I have trusted him farther than any living man. He was my detective, banker, and everything else in Colorado, New Mexico, and the other wild country I was in. The nearest and only bank was at Denver, and when we carried money I gave it to Bose, for a thief would never think of robbing him – never think of looking in a Negro’s bed for money.”

Cowhands at Rio Grande Plain, early 1900s

Bose Ikard was one of thousands of African American cowpunchers who drove cattle up the trails from 1865 until 1890. They whisked Texas beef to urban markets for “thirty dollars a month and grub.” A largely unhindered outdoor life, fair treatment, and decent pay attracted thousands of African Americans, Mexicans, Indians, and poor whites.

But these intrepid Westerners often had to ride a largely ungoverned and violent trail. Periodically, as if from sheer exhaustion, the cattle frontier would lapse into peace and tranquility. In Texas, a visitor noted, “men were seldom convicted, and never punished… if you want distinction in this country, kill somebody.” By 1877 the Texas “wanted” list numbered five thousand men and every race, religion, and color was included.

The first man shot in Dodge City, Kansas, was a tall cowhand named Tex, and he was African American. Tex was standing on a Dodge street, there was gunplay, and a stray bullet took his life. The first man arrested and jailed in Abilene’s new stone jail was Black and he was not innocent. Infuriated by his imprisonment, his white and Black trail crew rode into town, pulled the bars out of his cell, rescued their buddy, shot up the place, and rode back to camp.

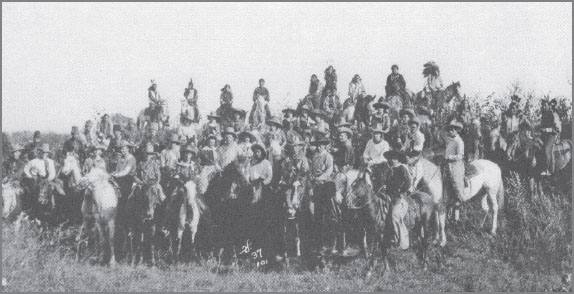

Texas cowboys on horseback

Estimations of the number of African American cowhands vary, but the most reputable source on the subject has been George W. Saunders, president of the Old Time Drivers Association. He estimated that from 1868 to 1895, “fully 35,000 men went up the trail with herds” and “about one-third were negroes and Mexican.” Recent authorities accept Saunders’s figures, and have agreed that at least a fourth of the riders were of African descent. The average trail crew of eleven probably included two or three African Americans, and one or two Mexican Americans or Native Americans. Some African Americans served in all-Black trail crews and others worked alongside whites as drovers, cooks, and scouts.

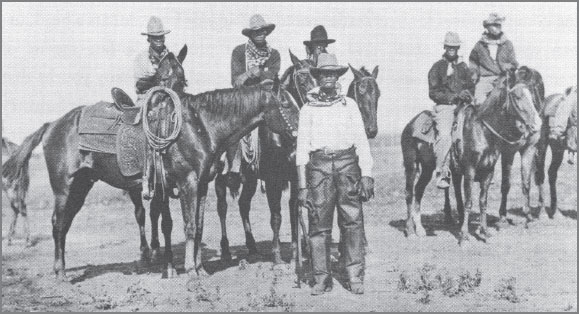

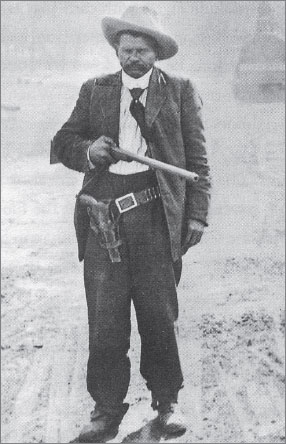

Judge Roy Bean of Texas tries a horse thief as four Black cowhands (left) look on.

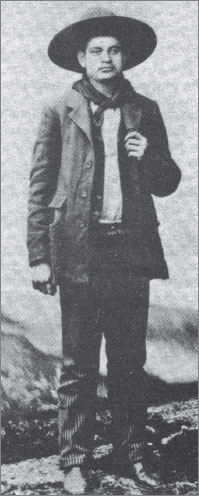

Cowhand Arthur L. Walker

Some cowhands of African descent had begun as enslaved people and were roping and branding cattle before they became free. Others headed west after Emancipation, seeking a life where skill would count more than skin color. Most came to live by the law, but a few rode in to break it.

Cowhands were ordinary men who possessed outdoor skills and a strong love of horses and cattle. Daily life on the range was more often hard, tedious, and lonely than filled with high adventure. However, danger lurked at any turn in the road or ford of the river, herds became unruly, and nature repeatedly offered the shocking and unforeseen.

A rough outdoor fairness grew out of the work’s inherent cooperative nature and interdependence. Cowmen had to help and stand by each other. Sleeping arrangements often found ranch owner, trail boss, drovers, and cooks of every race under the same blanket. Thwarted by lack of capital and racial barriers, only a few men of color were able to rise to foreman, trail boss, or ranch owner.

A Colorado cowpuncher (date unknown)

A fancy Telluride, Colorado, bar and game room, with a Black man on his knees doing some cleaning

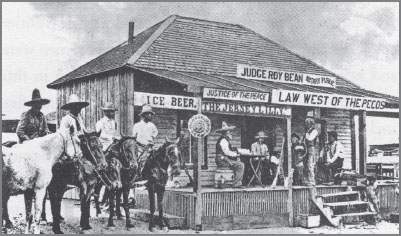

Dodge City’s Long Branch saloon had bartenders of both races in the 1800s.

Johnnie Deivers’s Place in Breckenridge, Colorado, in 1895. Bob Lott is standing alongside his white friends.

The multicultural patrons of this Klondike, Alaska, saloon pose for the camera in 1901.

Though historian Kenneth W. Porter believes that the Black range riders probably suffered less discrimination than they would have in any other occupation open to them at the time, discrimination did exist on the trail and at the ranch. Many were hired, according to a white cowhand, “to do the hardest work around an outfit” – as broncobusters. In his 1936 “Tribute Paid to Negro Cowmen” in Cattlemen magazine, Hendrix wrote, “They did as much as possible to place themselves in the good graces of the [white] hands.” He told of cowhands who would take “the first pitch out of the rough horses… in the chill of the morning, while the [white] cowboys ate their breakfast.” When subjected to hazing, African American cowmen relied on a tactful restraint rather than retaliatory fists and six-guns.

But not all. John B. Hayes, or “The Texas Kid,” born in Waco in 1881, responded to “For Whites Only” signs in saloons by asking for a drink, and when refused, would back his horse through the swinging doors and shoot out the lights. Jess Crumbly of Cheyenne, six foot four and 245 pounds of simmering temper, was nicknamed “Flip,” because, recalled a friend, “when he hit you you’d flip.” Crumbly could settle disagreements by showing two brawny fists that knew no color line. Henrietta Williams Foster, who also rode as a cowhand, reportedly killed a man who raped her.

Since existence was perilous enough without needless gunplay, cowhands tried to reach peaceful solutions. Despite the presence of former Confederate soldiers among trail crews, clashes between Black and other cowboys were few. More white gunfire was directed at Native Americans and Mexican Americans.

Cowhands assemble at a Bonham, Texas, fair.

Jess (right) and his Apache friends

Racial discrimination, however, repeatedly appeared, arriving in the wagons that brought large numbers of white wives, daughters, and their families from Eastern states. These newcomers, particularly men, began to demand the East’s “protective” barriers. The larger and more stable a Western community became, the more likely it would exude intolerance, practice forms of discrimination, and demand segregation. In newer settlements, particularly those with few white women, cowhands of color were less likely to encounter barriers. Cattle drive towns, even in Texas, enforced only an informal segregation in saloons. They served Blacks at one end and whites at the other, and cowhand camaraderie repeatedly challenged this barrier. This was particularly true in multicultural Oklahoma. However, when it came to houses of prostitution, Black men often faced warnings or entered at their own risk.

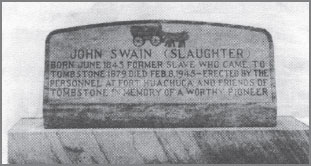

Some Black cowpunchers developed extraordinary talents, and a few were cut in the heroic mold. John Slaughter’s fearlessness matched his giant frame. When Tombstone, Arizona, murderer Frank Leslie tried to jump his claim, he chased him away. When boxing champion John L. Sullivan came to Tombstone in 1884 and offered $500 for anyone who would last two rounds with him, Slaughter volunteered. He even landed the first punch. But once the champ got busy, Slaughter was carried out of the ring.

John Slaughter was a large, strong, and fearless cowhand who lived a long, eventful life.

Jesse Stahl, rodeo champion

Britton Johnson, described by a friend as “a shining jet black negro of splendid physique,” was considered the best shot on the Texas frontier. In October, 1864, Johnson returned home to find Comanches and Kiowas had raided his community, killing his infant son and carrying off his wife, their three other children, and some white settlers, including children. Johnson persuaded the survivors he could rescue their loved ones, and rode off. He was able to enter the Indian village posing as a warrior-recruit or as a man willing to trade horses for prisoners. One tale holds he bartered for their liberty with horses, but another claims he conducted a harrowing night escape that rescued everyone.

In 1874 Willie Kennard, forty-two and a former U.S. cavalryman, rode into Yankee Hill, Colorado, a fearful town in the grip of hardened criminals. When he applied for the marshal’s job, the mayor told him that Yankee Hill’s white citizens would drive him out before he could confront a gunslinger. When Kennard insisted on a chance, the mayor slyly proposed a test – that he arrest Caswit, a vicious outlaw who had raped a teenager and shot her father. Kennard strode into Gaylord’s saloon and confronted Caswit, who drew his two Colt .44s. Kennard blasted them out of his hands and marched him to jail. For three years Marshall Kennard tamed Yankee Hill before he rode into the sunset.

On February 1, 1898, an African American was publicly lynched in Paris, Texas.

It would be a mistake to assume from the tales of Johnson and Kennard that cowhands were particularly good marksmen. Most were poor shots, few were skilled at handling guns, and some were trigger-happy. A cowpuncher named Ben and his white comrades became so furious when an Indian stole Ben’s horse, they galloped into the thief’s village guns blazing. When the smoke cleared, no one was wounded, but Ben’s horse lay dead.

In the early decades of the twentieth century the frontier saga had its reincarnation in Wild West shows and rodeo performances. Crowds thrilled at acts of incredible strength, recklessness, and macho guts, but in a Jim Crow age they rarely saw cowhands of color. Prejudice had kept some from entering, and others lacked the cash or amiable contacts with the white rodeo promoters.

Peerless Jesse Stahl, riding a bronco named Glasseye in California in 1916, was considered one of the best riders of wild horses in the West.

Some, however, burrowed into rodeos. Mose Reeder of Cheyenne became “Gaucho the Coral Dog… because they wouldn’t allow colored to ride, and I would pass when I used that name.” The two Mosely brothers, though top rodeo artists, adopted Indian names. Robert J. Lindsay of Clarksdale, Texas, found “You could ride allright, but they would give you the worst horse.” Or, as Mose Reeder recalled, “those that didn’t buck so no points could be scored.” Barriers were more rigidly enforced as the era of segregation moved toward the 1930s. Black towns, such as Boley, Oklahoma, had to stage their own rodeos.

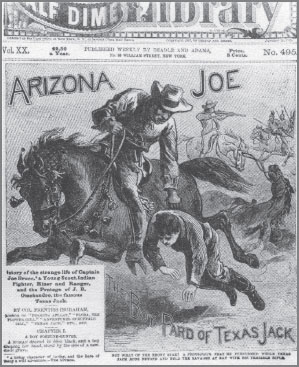

Texas Jack – a rare example of a Black cowhand hero in a nickel-Western novel

Africans carried vital traditions in handling horses and cattle which they then imported to Central and South American ranches and the plantations of the colonial South. These traditions surfaced when enslaved men and boys became horse trainers, stableboys, and jockeys. Therefore there was nothing unusual in 1875 when the winning jockey in the first Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs was African American. Hardly anyone would have bet the winner would be white, and the reason was simple arithmetic. Of the fourteen horses that lined up at the starting gate, thirteen carried Black jockeys.

The greatest jockey of the nineteenth century was Kentucky-born “Ike” Murphy, who began racing horses when he was fourteen. In 1882 Murphy won forty-nine of fifty-one races at Saratoga, New York. He became the first jockey to win the Kentucky Derby three times (in 1884, 1890, and 1891). In 1896, thirty-five and still young and full of life, he died of pneumonia.

Black jockeys

Ike Murphy

In 1901 and 1902 Jimmie Winkfield was the last African American jockey to win the Kentucky Derby. By then most African American boys who wished to follow in his footsteps found their path blocked. As horse racing became big business, the whites who controlled the purse strings also insisted that only whites would hold the horses’ reins. A proud tradition had ended.

Nat Love, born in a Tennessee slave cabin in 1854, was one of many young people who found their opportunities crushed by the reign of white supremacy after the Civil War. Among the “destitute conditions” that convinced Love at fifteen to head west was the lack of schools for children of color.

In 1869 Love “struck out for Kansas” and the beginning of what he would later characterize with rare understatement as “an unusually adventurous life.” He arrived in the bustling town of Dodge, “a typical frontier city, with a great many saloons, dance halls, and gambling houses, and very little of anything else.” Its various dens of iniquity apparently drew no color line, so Love and others were accommodated “as long as our money lasted.” He soon landed a $30-a-month job as a cowpuncher and was nicknamed “Red River Dick.” For more than a generation he took part in the long drives from Texas to Kansas.

Nat Love, known as “Deadwood Dick”

In 1907 Love wrote the only full-length autobiography by an African American cowhand. According to his narrative, he was captured by an Indian tribe and escaped by riding a hundred miles in twelve hours on an unsaddled horse. He was arrested when he tried to rope and steal a U.S. Army cannon, but his good friend Bat Masterson got him out of that scrape. He tried to rope a locomotive from his horse and both rider and mount landed hard. He rode his horse into a Mexican saloon and ordered two drinks – one for him, one for the horse. Should the reader find these tales hard to swallow, Love had a friend draw pictures that illustrated some of his most memorable moments.

Nat Love’s story is filled with exciting and almost unbelievable instances of courage, and his yarns are spun with typical Western braggadocio. In his first Indian fight he initially “lost all courage,” but after firing a few shots, he “lost all fear and fought like a veteran.” As his tale becomes more boastful, more crowded with confrontations, he invariably stands tall, a confident gunslinger, proud and loud, sometimes sounding more like a dime novel hero than a flesh-and-blood cowpuncher.

Although some might prefer Love to be more restrained, this was neither his nature nor his style. With obvious relish and jaunty self-assurance, he fought Indians, braved hailstorms, battled wild animals and men, and lived to tell the vainglorious tale.

One has to be impressed by Love’s miraculous invincibility. At one point he writes, “I carry the marks of fourteen bullet wounds on different parts of my body, most any one of which would be sufficient to kill an ordinary man, but I am not even crippled.” Another time, he relates, “Horses were shot from under me, men killed around me, but always I escaped with a trifling wound at the worst.” Of harrowing experiences that would have sent a lesser man back East, Love exclaims, “I gloried in the danger.” He also provided his twentieth century readers with the code of bygone era: “There a man’s work was to be done, and a man’s life to be lived, and when death was to be met, he met it like a man.”

While Love’s autobiography confirms the large-scale participation of African Americans on the long drives, he provides little insight into racial relationships, and he does not mention an instance of discrimination. To hear him tell it, he was accepted by all – from the psychopathic Billy the Kid, to the aristocratic Spanish maiden who was his first passion. He views Indians through white stereotypes – they are “terrorizing the settlers… defying the Government” and Mexicans are “greasers.” In each encounter with our hero, foes fall before his unerring aim.

On July 4, 1876, Nat Love entered the rodeo at Deadwood City in the Dakota Territory. He won the roping and shooting contests and reported: “Right there the assembled crowd named me ‘Deadwood Dick’ and proclaimed me champion roper of the Western cattle country.” This proud nickname he carried for the rest of his life, and into the subtitle of his book.

The wheels of progress finally caught up with Deadwood Dick and the others. The iron horse galloped across the landscape and made the long cattle drives unnecessary. No longer did cattle lose weight and market value with each mile up the Chisholm Trail; now powerful locomotives whisked Texas beef to Eastern consumers.

Nat Love left the range for a job as a Pullman porter, one of the least onerous positions of Jim Crow open to African American men. Now he roared swiftly across the badlands he once had ridden as a cowpuncher. But he never forgot those great days on the range, or his soulmates: Bat Masterson, Frank and Jesse James, and Billy the Kid.

Billy the Kid, the psychopathic killer who murdered twenty-one men in cold blood before he was twenty and was shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett, had a handsome counterpart in Cherokee Bill. Born on the military reservation of Fort Concho, Texas, Cranford Goldsby or Cherokee Bill started life in an atmosphere of respect for the law. His father, Sergeant George Goldsby, served in the Tenth Cavalry. But when Bill was only two, his father led his men in a gun duel with white Texans, and fled to avoid trial.

Cherokee Bill

Bill’s mother, Ellen Lynch, remarried and suddenly there was no room for the boy, aged twelve, in her new marriage. He fell in with bad company, and at eighteen he shot and wounded Jake Lewis, a Black man who had beaten him fairly in a dance hall fistfight two days earlier.

Cherokee Bill fled to the hill country, joined the Cook brothers’ outlaw gang, and soon scored his first notch, a pursuing posseman. Witty, virile, with long black hair touching his shoulders and a charming smile, he found a host of girlfriends who provided him with shelter and comfort as he eluded the law. Unlike white sheriffs and marshals, he was on good terms with Oklahoma’s Creeks, Seminoles, and Cherokees, so he could ride across their land without challenge.

Cherokee Bill was noted for his skill with firearms and particularly his ability at rapid fire. He once told a friend that although his shooting was not always accurate, it would “rattle” his opponent “so he could not hit me.” This skill, and a murderous reputation, kept posses at a distance.

Cherokee Bill and his mother, Ellen Lynch, who advised him: “Stand up for your rights. Don’t let anyone impose on you.” This was not a problem for him.

But posses could be persistent. When Cherokee Bill and Bill Cook tried to collect their $265.70 checks the U.S. government paid for confiscated Cherokee land, they found themselves in another gunfight. A month before his twentieth birthday, Cherokee Bill was captured and “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker of Fort Smith, Arkansas, who in twenty-one years sent seventy-nine men to the gallows, sentenced him to death.

In his cell beneath the courthouse, someone – a rumor points to Ellen Lynch – smuggled Cherokee Bill a six-gun, which he used to break out, kill another deputy, and wound others before being subdued. This time Judge Parker thundered the young man was “the most ferocious monster,” and referred to his “ferocity,” “passion for crime,” and capacity to “burn, pillage and destroy.”

Surrounded by lawmen of both races, Cherokee Bill was brought to Fort Smith for trial before “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker.

On a sunny day in 1896 Cherokee Bill awoke “at 6, singing and whistling,” and strolled to the gallows accompanied by his mother. Asked if he had any last words for the crowd, tough to the end, he replied, “No, I came here to die, not make a speech.”

The only photograph of the Rufus Buck gang, shows five slouching, smirking boys – some faces still showing a puffy baby fat – staring vacantly into a camera. None exhibit a demented or ferocious look, and they appear more muddled than evil. Do these faces reveal youths capable of the hideous crimes of rape, pillage, and murder against innocent men, women, and children? The handcuffs that join them are the only indication that this is their last day on earth.

The Rufus Buck gang on their last day on earth. Left to right: Maoma July, Sam Sampson, Rufus Buck, Lucky Davis, and Lewis Davis.

When Rufus Buck, Sam Sampson, Maoma July, and Lewis and Luckey Davis first rolled up a series of minor juvenile crimes, Judge Isaac Parker placed them in jail for a while. That was kid’s stuff. But in July 1895 they began a thirteen-day spree that took more lives than the infamous Dalton and Starr gangs combined.

Their wild rampage began with the murder of John Garrett, a Black Indian U.S. deputy marshal, near Okmulgee. They thought he was keeping too close an eye on them. Then they began to work in earnest, killing ranchers, small storekeepers, widows, farmers, and even a child. They took cash, gold watches, clothing, and boots, but theft was just an afterthought. They were enjoying themselves. The Muskogee Phoenix reported the gang’s crime spree but insisted that “details are too revolting to publish.”

The five outlaws voted three to two to let a white victim live, another time they shot a Black child in the back, and another time they raped and killed an Indian woman. At the Hassan family farm Rufus Buck announced “I’m Cherokee Bill’s brother.” Then, holding her husband at bay with Winchesters, they forced Mrs. Hassan to prepare a big meal, and after dinner, raped her.

On a warm summer day, reported the Muskogee Phoenix, a posse of “hundreds of men, whites, Indians and Negroes” turned out to hunt down the Rufus Buck gang. Trapped in a cave, they surrendered without a wound after a wild shootout.

The five were indicted for the rape of Mrs. Hassan and the murder of Marshall Garrett. Huge crowds assembled for a two-day trial that featured Mrs. Hassan’s lurid testimony, which brought tears even to the eyes of stoic Judge Parker. After one of the gang’s five defense attorneys told to the court, “You have heard the evidence. I have nothing to say,” the jury reached a guilty verdict, and the young men were sentenced to die.

The prisoners spent a last night singing and praying. Each accepted baptism by Father Pius of the German Catholic Church. There was quiet at the gallows, except for Lucky Davis who, seeing his sister, shouted “Good bye, Martha.” After the traps were sprung that July day, citizens of the Indian Territory agreed life was safer.

Mary Fields, six feet tall, two hundred pounds, and carrying a .38 Smith and Wesson strapped under her apron, became a legend in Cascade, Montana. One of the most memorable characters to stride the Rocky Mountain trails, she was vividly remembered by actor Gary Cooper who knew (and adored) her from the time he was nine.

Born in a Tennessee slave cabin during Andrew Jackson’s administration, Mary Fields began her Western career in 1884 hauling freight for Mother Amadeus and the Ursuline nuns at St. Peter Mission in Cascade. One night, while driving her wagon for the mission, wolves attacked. Her horses bolted, dumping Fields and her supplies on the prairie. She spent a lonely night surrounded by wolves, keeping them at bay with her rifle.

“Stagecoach Mary” Fields of Cascade, Montana

During her ten years at the convent, Fields proved a match for any who might try to trample her rights. When a hired hand crossed her, the two settled matters in a shootout. Though no one was wounded, the bishop, having heard complaints about her irascibility, ordered Mother Amadeus to fire her. In Cascade, Fields twice launched restaurants and twice went broke because she fed those who could only promise to pay.

In 1895, Mother Amadeus helped Mary Fields land a job with the U.S. postal service. For the next eight years she delivered letters regardless of terrain or subzero weather – “never missing a one,” recalled Gary Cooper. In her sixties she drove a stagecoach and was known as “Stagecoach Mary.”

At seventy, Mary Fields ran a laundry and spent time in the local saloon, drinking and smoking cigars with card-playing male friends. She left the saloon one day to confront a customer who had failed to pay his $2 laundry bill. She knocked him down with one blow, said “His laundry bill is paid,” and returned to her friends. When her laundry burned down in 1912, neighbors rebuilt it for her.

Gary Cooper remembered Mary Fields as a woman who helped “conquer and tame the Old Wild West.” Years later he recalled: “The town mourned her passing and buried her at the foot of the mountains.” Mary Fields was only the second American woman in history to drive a U.S. mail route.

In 1929 two noted Dodge City residents, Wyatt Earp and Ben Hodges, were laid to final rest. Both men earned their keep not at farm labor or cowpunching, but at cards. Historian Floyd Streeter has noted that Earp was “up to some dishonest trick every time he played,” and so was Ben Hodges. But both died of natural causes, unlike the many desperadoes they befriended.

Two of the surviving photographs of Ben Hodges show him armed with his trusty shotgun and six-gun. But these convey a false impression. Hodges relied less on lethal weapons than gentle persuasion – he might be called “the fastest tongue in the West.”

From the moment he arrived in Dodge City with a Texas trail crew and heard about an unclaimed Spanish land grant, he summoned wit and words to get ahead. Though his father was Black and his mother was Mexican, he claimed descent from an aristocratic Spanish family, galloped off to Texas and returned with “proof.” He did not win his case, but he captivated friends and perfect strangers with his scam, and convinced Dodge City he was a fine showman.

Hodges persuaded the head of the Dodge City National Bank to lend him money, and got the head of the local railroad to give him a free pass. Brought to trial for rustling a herd of cattle, he argued his own case. His masterful two-hour dramatic summary mixed humor, pathos, and lies: “What me, the descendant of old grandees of Spain, the owner of a land grant embracing millions of acres, the owner of gold mines and villages and towns situated on that grant of which I am sole owner, to steal a miserable, miserly lot of old cows? Why, the idea is absurd. No, gentlemen, I think too much of the race of men from which I sprang, to disgrace their memory.” Somewhat bewildering was his later claim that he was only a poor cowboy surrounded by personal enemies. Drama trumped consistency, however, and the jury acquitted him.

Ben Hodges, con man of Dodge City, Kansas

Despite his reputation as a forger, rustler, and card cheat, Hodges asked the governor of Kansas to appoint him a livestock inspector. After all, he pointed out, he had always been a loyal Republican. At this point Hodges’s cattlemen buddies, seeing a wolf asking to guard the sheep pen, persuaded the governor to veto this dread possibility.

When Ben Hodges died, Dodge City residents decided to bury him in the Maple Grove Cemetery for old-time cattlemen, cowboys, and other decent citizens. Why would you bury him among the best citizens? a pallbearer was asked. “We buried Ben there for a good reason,” he said. “We wanted him where they could keep a good eye on him.”

Born in 1867 in Orangeville, Texas, the eldest of eight children, to a formerly enslaved couple, Matthew Hooks learned to read, helped bring up his sisters and brothers, and developed a deep sense of personal responsibility. “They made me rock the cradle for my brothers,” he said, “and I’ve been rockin’ somebody’s cradle ever since.”

Thin and wiry as a boy, Hooks was nicknamed “Bones.” At seven he could do a man’s job, and by fourteen he came to love horses, learned how to break those who never quit bucking, and knew how to survive by outguessing their wildest moves.

When the young Hooks was told Clarendon in the Texas Panhandle “was the white spot of civilization,” he decided to live there, since he was a good Christian who did not drink or curse. It took many years for the town to accept him. Hooks was also a keen observer who differentiated between good women and those men who enjoyed saloons and gambling: “Credit for the advancement on the Plains belongs to the pioneer mothers,” he later wrote. “When the men brought their wives to the Plains the women demanded milk cows, chickens, schools, churches and all the attributes of civilization and culture.”

More than a few times white women stepped forward on his behalf to confront white bigots. One woman pointedly answered a man who objected to eating with Hooks, “Everyone is treated alike at my table.” His skills much in demand, Hooks was hired by leading ranchers in West Texas. Once, when innocently found in the company of two white cattle rustlers, he was questioned and let off, but they were hanged.

Matthew Bones Hooks (left) and other Texas cowhands in 1903

Hooks joined many cattle drives from the Pecos country to railheads in the northern Panhandle. When he opened a store near Texarkana, night-riding Klansmen closed it down. However, in 1894, after he was granted land for a Black church in Clarendon, he brought a preacher from Fort Worth to begin an African American community. A conservative man by nature, he favored Republican presidential candidate William McKinley while most of his white friends favored William Jennings Bryan and the Populists.

In his early thirties, Hooks married Anna Crenshaw, “a good woman, a good cook and a wonderful housekeeper.” In 1900 the couple worked at the Elmhurst Hotel in Amarillo, he as a porter and she washing and ironing the linens. Hooks became the first man of color chosen to serve on a jury and asked to join the Western Cowpunchers Association of Amarillo and the Western Cowboys Association of Montana.

At forty-three Hooks could still ride a horse described as “a thousand pounds of dynamite” to a standstill. He was still committed to building Black towns: “When I was a boy everywhere I went, folks would say, ‘We’re not goin’ to let any Negroes live here.’ But I said to myself, When I get grown I’m goin’ to build a town right beside yours, and not let any white folks live there.” Influenced by the militancy of Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois, in 1930 he built North Heights, a twenty-eight-square-block town northwest of Amarillo, and it grew into a successful residential and business community with thirty-five families, four churches, an elementary school, a high school, and a general store. Town fathers planted a tree named after each child so they could watch them grow, named their park after Hooks, and later erected a statue to him.

Hooks went on to found Black historical societies, tutor underprivileged children, and donate money to those in need. In 1949, when he needed medical aid but had spent his money on others and had to leave the local hospital, his friends raised the money for a housekeeper.

Hooks gave many lectures and left important notebooks about his adventures in Texas. He liked to tell how he had arrived early in the Panhandle: “Folks talk about Judge Bean and the Law West of the Pecos, but there wasn’t no law out here then.” He died in 1951 at eighty-three.

In 1900 Isom Dart, a tall, handsome cattle rustler, was only fifty-one when he was shot in the back and killed by Tom Horn, a notorious bounty hunter. Dart had tried to go straight many times but never succeeded, though some considered him a good man.

Born in slavery in Arkansas in 1849, Dart first developed his talents as a thief when Confederate officers sent him off to forage for them during the Civil War. He drifted into southern Texas and Mexico and worked as a rodeo clown, then he and a Mexican teamed up to steal cattle in Mexico and sell them in Texas.

Isom Dart, cattle rustler

Dart moved to Brown’s Park, Colorado, a haven for cattle thieves. For a time he gave up rustling for prospecting and then broncobusting. “No man understood horses better,” said one friend. Another added, “I have seen all the great riders, but for all around skill as a cowman, Isom Dart was unexcelled… He could outride any of them; but never entered a contest.”

But in a few years Dart was back in a rustler’s saddle, a member of the Tip Gault outlaw gang. One evening while he was burying a friend, the rest of the gang were ambushed and slain. Dart survived by spending the a night in the grave alongside his buddy.

Isom Dart and fellow cowhands at Brown’s Park, Colorado

Dart tried time and again to flee his rustler past, but each time he slid back. Some people described him as “a laughing sort of guy” and “a good man, always helpful.” “I remember Isom as a very kind man. He used to ‘baby-sit’ me and my brother when Mother was away or busy,” wrote an elderly woman who still treasured her photograph of Dart, and insisted that people hear about his decent side.

Arrested many times for rustling, Dart was never convicted. In Sweetwater County, Wyoming, he probably made the best case of any criminal while being driven to jail by a deputy sheriff. The deputy’s buckboard ran off the road, injuring the deputy but leaving Dart unhurt. Dart gave him first aid, calmed the horses, lifted the buckboard onto its wheels, and drove the lawman to the hospital at Rock Springs. Then Dart left the buckboard at the stable and turned himself in at the jail. In a land where cattle rustling was a capital offense, this was seen as proof of innocence and he was released.

Dart was both generous of heart and unlucky in love. When Tickup, a Shoshone woman with Mincy, her daughter of nine, fled Pony Beater, her abusive Ute husband, Dart rushed to help the two to safety and soon fell in love with Tickup. Pony Beater tracked the three down, tied up Dart, took his possessions and rode off with his prisoners. Dart freed himself and took off to find his new family, only to discover that life changes. Tickup had killed Pony Beater when he fell asleep, and took Mincy to Idaho. By the time Dart arrived to claim his love, Tickup had a new husband. An enraged Dart charged at the man, but Tickup, ever resourceful, used a stone ax to stun him. Nursing a badly cut ear, a heartsick Isom Dart rode back to Brown’s Park and bounty hunter Tom Horn.

In the 1500s domesticated horses, a mixture of North African barbs, Arabian steeds, and Andalusian horses, were brought to the New World by Spain’s conquistadores. From Mexico they were led northward, where they bred with strays of Spanish origin to produce mustangs, noted for their endurance but almost impossible to control. In herds of twenty to three dozen, they grazed freely in ranges of twenty-five to fifty miles, a stallion in command.

For their long drives, which used as many as a hundred horses, cattlemen eagerly sought these mustangs. Considered more valuable than cattle, they were headstrong, resistant to restraints, and their leader stallions were cagey and hard to deceive. Cowmen developed techniques to seize or trap herds, but they required many men and resulted in more mustangs killed then corralled.

Then Bob Lemmons rode in. Born in Lockport, Texas, in 1848, to Cecilia, who was enslaved, and an unknown father, Lemmons’s dark-skin, high cheekbones and straight, shoulder-length hair indicated his Indian and African ancestry. Freed at seventeen during the Civil War, by 1870 he had taught himself to read, and owned land, sheep, cattle, horses, and goats valued at $1,140.

Lemmons’s “walk down” required him to become part of a herd and get it to follow him as they would a stallion. His singularly gentle technique meant becoming one with the herd, traveling with them, letting them get used to his smell, clothes, and body. It took limitless patience and many days. He explained: “It wasn’t long before they wouldn’t run from me, and then I got ’em to where they trusted me, because ever’ time they’d scare, I’d scare and run as hard as they did. Sometimes I’d scare first and away we’d go, with me in the lead and them follerin’ me. I soon have a whole bunch runnin’ with me everywhere I went.”

A humble man, Lemmons had a quick wit and a gift for storytelling, and he rejected violence. He married, his family grew to eight children, but only one survived him. When he died in 1947 he owned more than twelve hundred acres of land, and he had the admiration of his community. Folklorist J. Frank Dobie interviewed Lemmons and wrote: “What is it inside some individuals that makes horses untamable by others, submit to them gently?… The horses would follow him like mules magnetized by a bell mare.” Bob Lemmons, Dobie concluded, “actually became the leader of a band of wild horses that followed him into a pen as fresh as they had been when he first sighted them.”

Lemmons’s gift was known far and wide in his own day, and today appreciation for his peaceful contribution is growing.

Daniel Webster Wallace, born into slavery in Victoria County, Texas, was freed at twelve in 1860. He took a job that paid fifteen silver dollars and joined his first trail drive, riding point at the head of a herd. When he worked for a rancher who owned eight thousand roaming cattle, he learned his skills fast. Wallace raced after straying horses and cattle, learned to handle firearms, endured stampedes, battled rustlers, took part in range wars, survived ambushes, buried two young friends, and once punched a white man who tossed a racial insult his way.

At twenty-five, Wallace had saved two-thirds of his monthly salary and bought a homestead. Then he decided to return to high school to learn to read and write. He met Laura Owen, another student, and they married.

A white friend in Fort Worth gave Wallace a letter of credit for $10,000, which he used to buy Hereford cattle, invest in one of Loraine’s first windmills, and pay his bills for twenty years. He and Laura owned 8,820 acres and an eleven-square-mile ranch. The Wallaces paid off their mortgages, built a modern home, and cross-fenced their land. They saw their four children educated.

Wallace had a reputation for feeding hungry Indians. He also lent money to poor friends and donated to educational projects, including a school in Colorado City later named after him. He was welcomed to the Texas and Southwest Cattle Raisers Association. The Cattleman, a newspaper, reported that he began to lecture about “the country as he first saw it more than half a century ago, unsullied by barbed wire and train smoke, a cowman’s paradise of running water, grass covered hills, and wide fertile valley where the antelope played.”

Bill Pickett (second row, third from right) and the 101 Ranch Wild West Show. His two assistants are Will Rogers (fifth from right) and Tom Mix (seventh from right).

Zack Miller, owner of the huge, sprawling 101 Ranch in Oklahoma, described Bill Pickett as “the greatest sweat and dirt cowhand that ever lived – bar none.” But Pickett was far more. He invented bulldogging, the most famous rodeo sport and the only one of the eight rodeo sports credited to an individual.

Bill Pickett aboard “Spadley” at a rodeo

Bulldogging involves riding one’s horse after a steer and then leaping out of the saddle to grab each of the steer’s horns with a hand. Then with boot heels digging into the ground, Pickett would wrestle the giant beast into the dust by twisting its head back and its nose up. Like a ballet dancer, he then turned the animal over, and by slipping to one side he dragged it along until both came to a dusty stop. Pickett not only did this with relative ease, but also completed his daring act with a unique flourish: he sank his teeth into the steer’s upper lip and raised his hands into the air to show his only grip was teeth to lip.

Pickett was born in 1870 to poor Black Cherokees, the second of thirteen children. Fascinated with animals, he left school after the fifth grade for a life in the out-of-doors. As he developed riding and roping skills, he noticed that a bulldog could leap up and bite a steer’s lip and it would render the huge animal compliant. He used this to find his own path to fame. In 1890 he married Maggie Turner and they had nine children.

In 1907 Pickett signed a contract with the Miller Brothers’ famous 101 Ranch Wild West Show, where at various times his assistants included Will Rogers and Tom Mix, both of whom later became successful in show business and Hollywood. The 101 Rodeo performed in Texas, Mexico, Argentina, and Canada. In 1912 alone the 101 gave more than four hundred performances in twenty-two states and three Canadian provinces, with Pickett as the chief box-office draw. In 1914, when the crew spent three months in Europe, Pickett learned to speak “a very high grade of German.” The 101 also performed before King George and Queen Mary, who exclaimed “Most wonderful exhibition! Most wonderful exhibition!”

His muscular strength tightly focused, his slight, five-foot-seven, 145-pound frame gliding through the air like a ballet dancer, Pickett became the most significant practitioner of Western lore. He also survived harrowing experiences. In El Paso, Texas, he brought down a large male elk, avoiding his knifelike antlers, by riding his back until he tired. He is also credited with throwing a buffalo bull. The first night the 101 crew opened in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, Pickett and Rogers had to gallop into the stands to corral a steer terrified by the bright lights. In Mexico City in 1908, Zack Miller bet $5000 Pickett could ride a bull for five minutes. Between the bottle-throwing audience and the bull, he was badly gashed, had three ribs broken, and barely survived his seven minutes on the bull’s back.

In time, calculated rashness caught up with precision acrobatics and Pickett broke almost every bone in his body. He died in 1932 after he slipped in a barn and a stallion kicked him in the head. Will Rogers, by then a famous actor, publicly mourned his mentor and told the New York Times how “Old Bill” thrilled millions with an act no other human being had ever done.

Riders of the 101 Ranch with Bill Pickett (first row, center, with white shirt)

He left a blank that’s hard to fill

For there never will be another Bill.

Both black and white will mourn the day

That the “Biggest Boss” took Bill away.

Colonel Zack Miller, cited in Ellsworth Collings and Alma Miller England’s The 101 Ranch, (Norman, Oklahoma), p. 172.

In 1971, two generations after his death, Pickett became the first African American voted into Oklahoma City’s Cowboy Hall of Fame; in 1987, with African American movie star Woody Strode officiating, a bronze statue of Pickett bulldogging was unveiled at the Fort Worth Cowtown Coliseum.

Pickett mastered the ferocious in nature not with weapons of death, but with a craftsmanship rooted in respect for life. His enduring monument is a bulldogging act that never ceases to entertain millions. His act offered larger lessons: how an ordinary individual can summon the courage, stamina, and skill to overcome life’s fearful beasts, and how one can live harmoniously with the untamed in nature.

Poster for a 1922 Bill Pickett movie