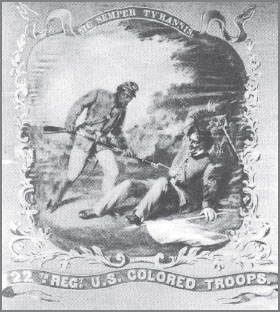

In the Civil War 178,958 African Americans had fought in a Union Army of one million, taken part in 449 engagements and 39 major battles, and been awarded twenty-two Medals of Honor. They earned the unstinting praise of their commanders in the field, and in 1864 their commander in chief in the White House admitted that without his Black troops “we would be compelled to abandon the war in three weeks.”

Black men gained and quickly lost their right to vote, but in 1866 they won a permanent a right to serve in the U.S. armed forces when Congress authorized recruitment of African Americans to assist in the “pacification” of the West. By 1870 the goal of preserving peace with Native Americans – made impossible by Washington policy and the white appetite for Indian land – fell to 30,000 federal soldiers, including 2,700 former slaves.

In the Civil War, African Americans earned the right to serve in the U.S. Army.

Over the next two generations 25,000 African American men would pass through the ranks of the two Black cavalry and two Black infantry regiments. The average recruit was about twenty-three, an illiterate laborer or farmer seeking a stable job, steady income, and higher status. Soldiers were paid $13 a month with small annual increases. For African American units the army provided a chaplain to oversee education. “I felt I wasn’t learning enough, so I joined,” recalled soldier Mazique Sancho. Men who had not learned to read and write leaped at the opportunity, and despite a shortage of trained teachers, they made remarkable progress. In 1875 Chaplain George C. Mullins reported: “For the most part the soldiers seem to have an enthusiastic interest in the school. They are prompt in attendance, very orderly and cheerful. In learning to read and write many of them make astonishing progress.”

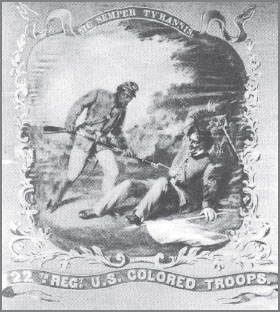

The Twenty-Fourth Infantry test blanket rolls for the U.S. Army in 1893.

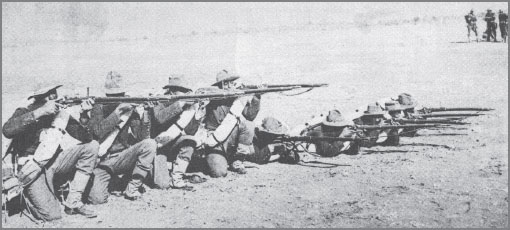

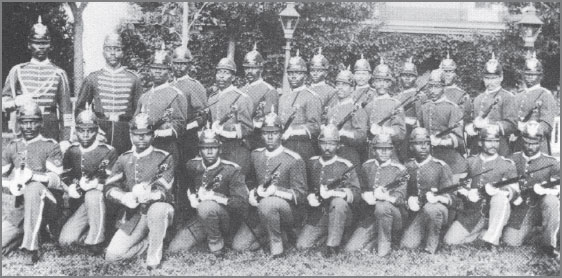

This 1893 photo shows Twenty-Fourth Infantry men using 1884 model 45/70 Springfield rifles with bayonets.

The Twenty-Fifth Infantry band, Fort Missoula, Montana, around 1900

The African American regiments, the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry and the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry, were mired in painful irony. Recruits were commanded by whites and denied the right to be commissioned officers. And they contributed to the final defeat of Native Americans, the first victims of racism in the Americas. Native Americans named them “buffalo soldiers” after an animal that provided them with clothing, food, and shelter.

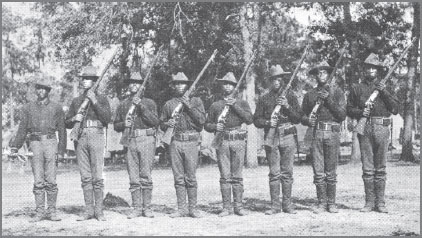

The Twenty-fourth Infantry at Los Angeles County, around 1898

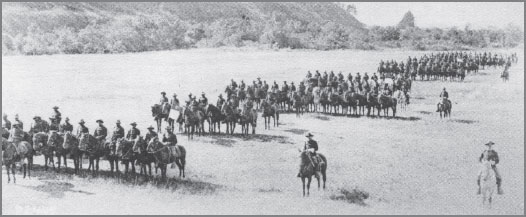

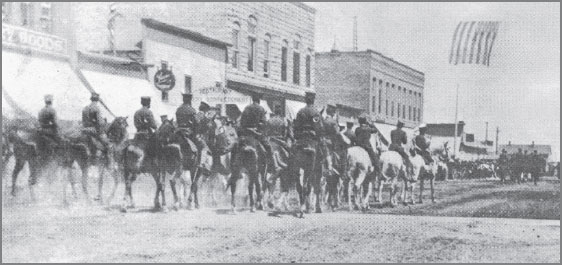

Mounted buffalo soldiers, around 1898

In an age that increasingly viewed Black men as either comic or dangerous and denied them decent jobs, army life offered reliable, dignified, and rewarding labor. It also provided those symbols by which man has traditionally cushioned a lowly status – pride in country, discipline, decent clothes, and faith in authority.

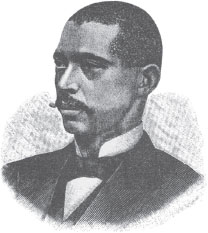

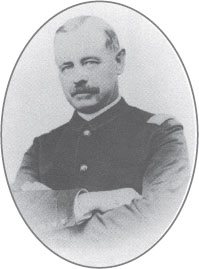

Soldiers follow orders and these men were no different. But some vehemently opposed Washington’s policies toward Native Americans and expressed their views. For example, George Washington Williams, sergeant major in the Tenth Cavalry, recalled he and his men felt “it is wrong to persecute the poor Indian” and that “white people would have to answer for their wickedness in the Day of Judgment.” When his company left for the frontier, he reported: “We felt that if there was an Indian near we would run and fall upon his neck and weep.” Appalled by a white officer who was “thirsting for Indian blood,” Williams decided “killing people isn’t a job for a Christian,” and he left the service. In 1881 he wrote a two-volume History of the Negro Race in America, the century’s most important Black historical study in this field.

George W. Williams, historian

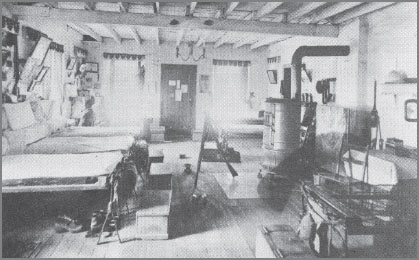

Camping out on the frontier

Some assignments had buffalo soldiers guarding Indians from white soldiers, lawmen, or civilians. In 1879 Texas Rangers were about to engage in a scalp-hunting foray against a Kiowa village when Tenth Cavalrymen blocked their path. In 1887 the Ninth Cavalry kept Colorado militiamen from charging into a Ute reservation. Buffalo soldiers also protected the Indian Territory from aggressive white intruders.

The men of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments comprised 20 percent of the U.S. Cavalry in the West and rolled up an outstanding record. They patrolled from the Mississippi to the Rockies, from the Canadian border to the Rio Grande, and occasionally were ordered into Mexico in pursuit of outlaws or Indians. Their white scouts included Kit Carson and Wild Bill Hickok.

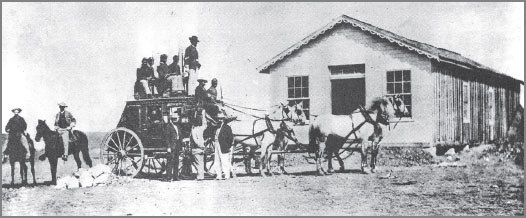

Black soldiers guarding a stagecoach

People may think it isn’t true, but the Indians never shot a colored man unless it was necessary. They always wanted to win the friendship of the Negro race, and obtain their aid in campaigns against the white man.”

Caleb Benson, Tenth Cavalry, 1875–1908, cited in Northeast Nebraska News, November 9, 1934 (Nebraska History, summer 1993)

Officers such as George Armstrong Custer rejected service in the regiments, as did many West Point graduates. On the other hand, General John J. Pershing was proud to earn the nickname “Black Jack” leading a company of the Tenth Cavalry against bandits and Indians in Montana, against Spaniards at San Juan Hill, and against Pancho Villa in Mexico. In 1921 Pershing wrote: “It has been an honor which I am proud to claim to have been at one time a member of that intrepid organization of the Army which has always added glory to the military history of America – the 10th Cavalry.”

Black Jack Pershing and his Tenth Cavalry men

Troopers of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry participated in almost two hundred engagements and won the respect of every military friend or foe they encountered. They suppressed civil disorders, chased Indians who left their reservations, arrested rustlers, guarded stagecoaches, built roads, protected survey parties, shielded mail carriers, mapped uncharted regions, and rescued settlers and other soldiers. In 1892 they ended a cattle war in Wyoming and two years later they preserved order when jobless citizens marched on Washington to demand economic relief.

A wounded Tenth Cavalryman, sketched by Frederic Remington

Particularly in East Texas, buffalo soldiers faced hostility from the people they defended, often former Confederate soldiers contemptuous of armed, blue-coated men. Jacksboro, Texas, had twenty-seven saloons for its two hundred white residents – tough cowpunchers and prostitutes who enjoyed baiting Black soldiers. One Texas citizen murdered a Black soldier and then killed the two African American cavalrymen who came to arrest him. A jury of his white peers found him not guilty.

The Ninth Cavalry at Fort Robinson, Nebraska

Black troops line up in 1899.

In 1867, when vigilantes lynched three Black infantrymen in Kansas, other Black soldiers returned to the town center and a blazing gunfight. In February 1878 a Black company from Fort Concho, Texas, armed with carbines, shot it out in a San Angelo saloon with local cowboys, gamblers, and pimps, leaving two men dead and several wounded. In 1900 in El Paso, Texas, after police arrested two Black infantrymen, others used their rifles to raid the jail. In the ensuing gun duel, each side lost a man.

At times soldiers of both races united against their tormentors. On February 3, 1881, in San Angelo, after a Black private was killed by a gambler and a white soldier was also slain, white and Black soldiers posted a handbill:

We, the soldiers of the United States Army, do hereby warn cowboys, etc., of San Angelo and vicinity, to recognize our rights of way as just and peaceable men. If we do not receive justice and fair play, which we must have, someone will suffer; if not the guilty, the innocent. It has gone too far; justice or death.

U.S. SOLDIERS, ONE AND ALL.

Two companies of enlisted men, one Black and one white, then marched into San Angelo, arrested the sheriff, and demanded he surrender the murderer in his jail. At that point a white colonel ordered the troopers back to Fort Concho.

Cannon firing at Fort Robinson, Nebraska

The Army brass consistently took a dim view of its buffalo soldiers. In Texas, General Edward Ord called them “with few exceptions, liars and thieves,” and General William T. Sherman told Congress he preferred to enter a battle with “5,000 white men.” The army high command also dealt buffalo soldiers an unfair hand. Captain Louis Carpenter, one of several white officers to earn the Medal of Honor leading Black troopers, complained that “this regiment has received nothing but broken-down horses and repaired equipment” – usually castoffs from George Custer’s favored Seventh Cavalry. Even the Tenth’s regimental banner was homemade, faded, and worn – unlike the silk-embroidered standard supplied by headquarters to white regiments. Not until 1891 were African American soldiers assigned to guard the national capital.

A buffalo soldier band

Buffalo soldiers, scholar William H. Leckie has shown, were consistently assigned to the most dreary forts: “Their stations were among the most lonely and isolated to be found anywhere in the country and mere service at such posts would seem to have called for honorable mention. Discipline was severe, food usually poor, recreation difficult, and violent death always near at hand. Prejudice robbed them of recognition and often of simple justice.”

From a remote Texas post, the white commander of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry described “everything saturated with rain, the dirt floor four inches deep of mud, and the men sitting at meals with their feet in more than an inch of water, while their head and back were being defiled with ooze from the dripping dirt roof.”

Punishments of African Americans, Leckie found, exceeded those of white soldiers. However, Black cavalrymen had fewer courts-martial for drunkenness, and boasted the lowest desertion rate in the frontier army. In 1876, the Ninth had 6 and the Tenth had 18 deserters – compared to 170 for the Third, 72 for the Seventh and 224 for the Fifth.

Black deserters found more places to hide than whites, including among Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and other people of color. Frustrated in his hunt for deserters among the ninety African American residents of Las Vagas, New Mexico, Lieutenant Matthias Day grumbled, “The whole colored population here seem to be in league with” his Black escapees, “and spy around to find out everything I do.”

Interior of barracks at Fort Shaw, Montana

Despite discriminatory conditions, morale among Buffalo Soldiers remained high, and a dozen men earned the nation’s highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor. The first recipient, Emanuel Stance, a sergeant in Company F, Ninth Cavalry, in two years had five encounters with Plains Indians and accounted himself so well that his captain was unstinting in his praise.

Others followed. Sergeant George Jordan of the Ninth earned his medal for two engagements. In one he commanded twenty-five troopers who “repulsed a force of more than 100 Indians,” read the official report. A few years later, in 1881, he and nineteen Buffalo Soldiers “forced back a much superior number of the enemy, preventing them from surrounding the command.” That same year another sergeant in the Ninth, Moses Williams, received his Medal of Honor with this citation: “Rallied a detachment, skillfully conducted a running fight of three or four hours, and by his coolness, bravery and unflinching devotion to duty in standing by his commanding officer in an exposed position under heavy fire from a large party of Indians, saved the lives of at least three of his comrades.” The heroism of other troopers is forever buried in terse military phrases such as “bravery in action,” “gallantry in hand-to-hand fight,” and “saved the lives of his comrades and citizens of the detachment.”

Fighting off an ambush

On June 25, 1876, Isaiah Dorman, a Sioux with African American ancestry, a friend of Chief Sitting Bull, and a highly trusted War Department courier and scout in the Dakota Territory, rode into history with General Custer. With Custer and 264 Seventh cavalrymen, he fell mortally wounded at the Little Big Horn. Sitting Bull reportedly approached the fallen Dorman and said, “Don’t kill that man, he’s a friend of mine.” After he gave Dorman a drink from his buffalo horn, he died. A Cheyenne later wrote: “I went riding over the ground where we had fought the first soldiers during the morning of the day before. I saw by the river, on the west side, a dead black man. He was a big man. All of his clothing was gone when I saw him, but he had not been scalped nor cut up like the white men had been. Some Sioux told me he belonged to their people but was with the soldiers.”

Neither extraordinary competence, courage, nor sacrifice led to an easing of Army discrimination. African American soldiers found it difficult to advance beyond sergeant, and were denied opportunities granted white recruits. Asked if he would form an artillery unit a Black man could join, Captain Henry Wright of the Ninth Cavalry answered, “He lacks the brains.”

Captain Dodge’s Colored Troopers to the Rescue is the title Frederic Remington gave this famous picture. For bravely leading buffalo soldiers against the Ute Indians at Milk River, a white officer received the Medal of Honor.

The Ninth Cavalry dining room

The last decades of the nineteenth century have been characterized by scholar Rayford Logan as “the nadir” of African American life. Citizens of color had little to sustain their spirits, he pointed out – except for the buffalo soldiers. Many Black homes proudly displayed photographs of these intrepid fighters.

The Ninth Regiment Cavalry, United States Colored Troops, was organized in New Orleans in 1866 under Colonel Edward Hatch and under the fifteen-year command of Major Albert P. Morrow. It became a tough, hard-hitting unit. Lieutenant Colonel Wesley Merritt, who with six companies of the Ninth rebuilt Fort Davis in Texas, called his troopers “brave in battle, easily disciplined, and most efficient in the care of their horses, arms and equipment.” The Ninth served in Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Utah, and Montana.

The Ninth Cavalry Band in Santa Fe Plaza, 1885

The Ninth Cavalry amusement room

The Ninth earned a reputation for always arriving in the nick of time to rescue settlers or troopers pinned down by outlaws or Indians. In Texas their fiercest foes included Mescalero Apaches, Kickapoos, and Mexican and U.S. bandits – all of whom crossed the Mexican border at will, something the troopers could not do. The Ninth’s duties included scouting for cattle thieves and marauders, providing escort duty for survey parties, picket and patrol duty, protecting river crossings, acting as couriers, guarding the Rio Grande, providing escort to cattle herds, securing prisoners, chasing Indians, and defending trains and wagons.

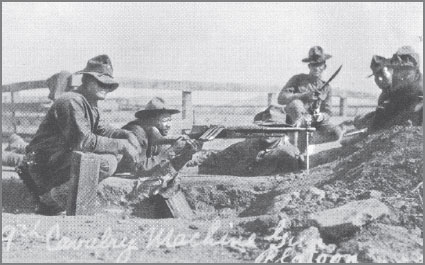

The Ninth Cavalry machine gun platoon

Trumpeters of the Tenth Cavalry

During the Ghost Dance rebellion of the 1890s, a company of the Ninth rode one hundred miles and took part in two fights in thirty hours to relieve the Seventh Cavalry. The company commander, Captain Dodge, earned the Medal of Honor, and his action was immortalized in a Frederic Remington drawing.

Mobilized at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1866, the Tenth Cavalry Regiment became a legend on the frontier. Their first commander, Colonel Benjamin Grierson, was a former music teacher famous for his spectacular six-hundred-mile cavalry raid into Confederate territory. Devoted to his job and his men, Grierson helped them form a regimental band. He and his fellow white officers contributed to the fund for musical instruments. Grierson’s wife wrote letters home for soldiers who could not write, and served as an informal volunteer lawyer for those in trouble with their officers.

Colonel Benjamin Grierson

The Tenth Cavalry at Diamond Creek, 1891

For a time the Tenth Cavalry constituted the only U.S. military presence in West Texas. They also made the first thorough exploration of Texas’s Staked Plains, a trackless wasteland, riding for days in temperatures of over 100 degrees. They discovered several good springs and found land with excellent grass. The report on their foray stimulated a migration by cattlemen, sheepmen, and homesteaders, but failed to mention the gallant horsemen who first crossed this land.

The Tenth Cavalry Band at Crawford, 1906

The majority of the inhabitants of that section, are a class that think a colored man is not good enough to wear the uniform of a United States soldier – near not good enough even to wear the skin of a dog.

They sneer at a colored soldier on the sidewalk and bar him from their saloons, resorts, and places of amusement. Why, when I was down there, one Sunday I thought I would go down to Point Isabella, on the Bay, to spend the day. So in company with a young lady I went down to the depot and purchased two tickets (taking advantage of the excursion rates then offered), boarded the train (which was only a little better than walking), went into the car and took a seat. When the train started, one of the so-called “Texas Rangers” came up to me and told me I was in the wrong place. I said “No, I guess not, I just read your law, and it says the Negro and white passengers will not ride in the same coach except on excursions.” He replied, “Don’t make any difference, you get out of here; you are too smart any way; I will break this gun over your head if you say much,” the meantime menacing me with a six-shooter, of the most improved villainous pattern and caliber. Well I obeyed his orders because I was alone and could not help myself. I knew that I was being treated wrong, but he held a “Royal flush,” and I only had a “four-card bob,” and I knew I could not “bluff” him.

A colored man who has the disposition of a toad frog (I mean one who can stand to be beaten on the back and puff up and take it) is all right; he can stay in that country. But those who feel hot blood running through their veins, and who are proudly and creditably wearing the uniform of a United States soldier; standing ready to protect and defend the American flag, against any enemy whomsoever, to obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officer appointed over them (which they have always done with pride and honor), cannot stay down there in peace with honor. The people do not want them either because they will probably not be able to carry out their favorite sport, hanging a colored man to a limb, or tarring and feathering him and burning him at the stake without trial, while the colored soldiers are stationed there.

Sergeant Vance Marchbanks in The Voice, December 1906, p. 549

The Twenty-Fifth Infantry at Missoula, Montana, around 1900

The Tenth patrolled Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona, battled Sioux, Apaches, and Comanches, and helped capture Geronimo and Billy the Kid. One of their most frustrating assignments was to keep the peace between angry settlers and cattlemen after barbed wire drew a steel line between the two.

The Twenty-Fifth Infantry at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, 1883

The Twenty-fifth Infantry Fort Missoula baseball team, 1902

The Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry Regiments also served on the Western plains. The Twenty-Fourth was organized in 1869 from two units scattered from Louisiana to Texas and New Mexico. Lieutenant Colonel William R. Shafter, an obese and lackluster officer, was its first commander. The Twenty-Fifth was organized in New Orleans in 1869 from remnants of the Thirty-Ninth regiment from North Carolina and the Fortieth in Louisiana.

Both regiments were dispatched to desolate Western garrisons and directed to defend the frontier from violence. In 1889 a small detachment from the Twenty-Fourth Infantry and the Ninth Cavalry were ambushed by bandits in Arizona as they guarded an army payroll wagon and its driver. Firing from a promontory, a band of outlaws pinned the soldiers down, wounded several, and made off with the strongbox. Paymaster J. W. Wham, who fought in sixteen Civil War battles under General Grant, found their bravery exceptional: “I never witnessed better courage or better fighting than shown by these colored soldiers, on May 11, 1889, as the bullet marks on the robber positions to-day abundantly attest.” For their courage under fire and fighting on despite severe wounds, Sergeant Benjamin Brown and Corporal Isaiah Mays were awarded Medals of Honor.

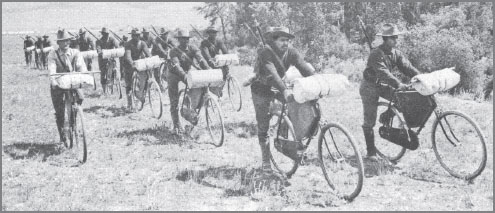

Soldiers from the Twenty-Fifth Infantry leave Missoula, Montana, in the first U.S. Army test of a bicycle corps, riding to St. Louis and back in 1899.

One of the most disgraceful chapters in U.S. military history is West Point’s refusal to protect its earliest African American cadets. Of the twenty Black candidates who entered West Point in the nineteenth century, only three graduated. The first cadet, James W. Smith of South Carolina, was harassed and then ousted from the academy for striking back at his tormentors by hitting one on the head with a coconut dipper.

Your kind letter should have been answered long ere this, but really I have been so harassed with examinations and insults and ill treatment of these cadets that I could not write or do anything else scarcely. I passed the examination all right, and got in, but my companion Howard failed and was rejected. Since he went away I have been lonely indeed. And now these fellows appear to be trying their utmost to run me off, and I fear they will succeed if they continue as they have begun. We went into camp yesterday, and not a moment has passed since then but some one of them has been cursing and abusing me… It is just the same at the table, and what I get to eat I must snatch for like a dog. I don’t wish to resign if I can get along at all; but I don’t think it will be best for me to stay and take all the abuses and insults that are heaped upon me.

James Smith, in The New Era, July 14, 1870

A court-martial hearing in the case of Black West Point cadet Johnson C. Whittaker

In 1880, Cadet Johnson C. Whittaker, after two years of academic success at the academy, was found tied to his bed, his ears slashed and his hair cut. He was charged with inflicting the wounds on himself and falsely accusing others; a court-martial found him guilty. In 1882 President Chester A. Arthur reviewed the case and found the evidence insufficient, but the Academy’s board again ruled against Whittaker, and he was dismissed.

Second Lieutenant Henry Flipper

The first African American graduate of West Point, Henry O. Flipper, was the son of a Georgia slave. He endured the rage of other cadets and instructors who would not speak to him, and in June 1877 graduated fiftieth in a class of seventy-six. Assigned to the Tenth Cavalry, he hoped to find better times. In 1881, Lieutenant Flipper was tried for “embezzling public funds and conduct unbecoming an officer.” He was acquitted on the first charge but found guilty on the second. For years after his discharge he wondered if the fact that he had gone riding with a young white woman while serving at Fort Concho had led to his conviction.

In 1880 Puck magazine published this cartoon on its cover.

Despite Lieutenant Flipper’s discharge, his extraordinary skills as a civil engineer led to his being hired by federal, state, and local governments. His work and incorruptibility resulted in the return of large portions of land to the public domain. Flipper served as a translator for the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, helped build a railroad in Alaska, and worked for the U.S. secretary of the interior. Many decades after his death Flipper was exonerated.

After his graduation from West Point in 1887, Lieutenant John Alexander, served seven years as an officer with the Ninth Cavalry in Nebraska, Wyoming, and Utah, earning the respect and trust of his men. He died suddenly in 1894 while on active duty. In 1918 the U.S. Army belatedly honored this “man of ability, attainments and energy – who was a credit to himself, to his race and to the service,” when it named a post in Virginia “Camp Alexander.”

Second Lieutenant Charles Young in 1889

Charles Young, the last African American West Point graduate of the nineteenth century, was assigned to the Tenth Cavalry in 1889 and began an illustrious career that would span more than three decades, the longest of the three graduates.

As a commander of Black Ohio volunteers during the Spanish-American War, Young took part in the charge at San Juan Hill. During Mexican border battles against Pancho Villa, he served with John J. Pershing in the Tenth Cavalry. In 1903 Young, speaking at Stanford University, rejected the accommodationist views of educator Booker T. Washington and said his people should assert their citizenship rights. He asked his audience: “All the Negro wants is a white man’s chance. Will you give it?”

At the outset of World War I, Colonel Young received his answer. He was suddenly dropped from active duty. Although the official explanation was “high blood pressure,” Young knew many wanted to prevent his assuming command of U.S. troops in the war to “make the world safe for democracy.” To prove his fitness, Young rode his horse from Ohio to Washington and back. But not until three days before the Armistice was he placed back on active duty.

Assigned to diplomatic duty in Africa, Young died there in 1922, and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. By the time of his death Young had mastered six foreign languages, written books of poetry, and composed music for violin and piano. Not until 1936 would another African American man graduate from the U.S. Military Academy.

Frederic Remington sketched this dismounted Tenth Cavalryman.

Born in New York and educated at the Yale School of Fine Arts and at the Art Students League, Frederic Remington became the great artist of the last frontier. Among his twenty-seven hundred drawings and paintings, sketchbooks, reports, and short stories are preserved rare glimpses of buffalo soldiers in action.

Frederic Remington sketched this mounted Tenth Cavalryman.

In the summer of 1888 Remington accompanied a unit of the Tenth Cavalry in Arizona. He brought the trained eye of a journalist, the hands of an artist, and a rare ability to rise above the era’s coarse stereotypes. “They are charming men with whom to serve,” Remington wrote. He addressed another issue: “As to their bravery, I am often asked, ‘Will they fight?’ This is easily answered. They have fought many, many times. The old sergeant sitting near me, as calm of feature as a bronze statue, once deliberately walked over to a Cheyenne rifle-pit and killed his man. One little fellow near him once took charge of a lot of stampeded cavalry-horses when Apache bullets were flying loose and no one knew from what point to expect them next. These little episodes prove the sometimes doubted self-reliance of the negro.”

Frederic Remington, second in line, sketched Marching in the Desert in Arizona with the Tenth Cavalry, in 1888.

A decade later Remington again rode with the Tenth Cavalry. He revealed that this outfit “never had a ‘soft detail’ since it was organized, and it is full of old soldiers who know what it is all about, this soldiering.” The media of the day treated Black men as brutes or buffoons, but Remington’s images were natural and genuine: “The physique of the black soldiers must be admired – great chests, broad-shouldered, upstanding fellows…”

A Frederic Remington sketch

A Remington sketch of the Tenth Cavalry on a Montana mountain pass in 1888

In a short story in Collier’s in 1901, “How the Worm Turned,” Remington responded to an early confrontation between troopers from Fort Concho and white criminals in San Angelo. His Black narrator reports how white Texans shot at Black soldiers “on sight.” After some whites brutalized a Tenth Cavalry sergeant, he and his men rode in to settle matters. They entered the culprits’ saloon, ordered a drink, then spun and opened fire. “When the great epic of the West is written,” wrote Remington, “this is one of the wild notes that must sound in it.”

A Remington party of buffalo soldiers from Fort Concho, Texas, shooting up Bill Powell’s saloon to revenge a wounded comrade shot by one of its patrons

Seminoles at Fort Clark, Texas

On July 4, 1870, more than two hundred Black Seminole men, women, and children crossed the Rio Grande to settle at Fort Duncan, Texas. For the only time in history an African people and its reigning monarch, John Horse, had negotiated their admission to the United States by formal treaty and arrived intact as a nation. In a treaty initiated by U.S. General Zenas A. Bliss, the nation agreed to have its young men serve as army scouts in return for family rations and eventually some land. Their desert skills would even the army’s odds against the cattle rustlers and desperadoes who kept the Rio Grande region in turmoil.

Charles Daniels; his wife, Mary; and daughter Tina

Seminole Negro Indian Scouts, 1889

The freedom-fighting record and many triumphs of these Seminole Negro Indian Scouts had begun in Florida before the Declaration of Independence. From 1850 until their return a generation later, they had served in Mexico as “military colonists.” Their unmatched desert skills had brought down a host of border scorpions and pacified Mexico’s turbulent Rio Grande border.

Men who could fire with pinpoint accuracy from the saddle were handed U.S. Sharps carbines, which allowed for faster, easier loading and action than any they had known. Civil War veteran Lieutenant John Bullis, their commander, was a diminutive, wiry, red-faced Quaker who gave them high fitness ratings except for “military appearance,” which he rated “very poor” – his response to their Indian dress and feathered war bonnets.

Lieutenant John L. Bullis, commander of the Seminole Scouts

Bullis and the Scouts survived the Texas desert on canned peaches and rattlesnakes. And they rolled up an unequaled military record. In twelve major engagements and twenty-six skirmishes, they never lost a man in battle or had one seriously wounded.

Scout Joseph Phillips described their relationship with Bullis: “The Scouts thought a lot of Bullis. Lieutenant Bullis was the only officer ever did stay the longest with us. That fella suffer just like we-all did out in de woods. He was a good man. He was a Injun fighter. He was tuff. He didn’t care how big a bunch dey was, he went into ’em every time, but he look for his men. His men was on equality, too. He didn’t stand and say, ‘Go yonder’; he would say ‘Come on boys, lets go get ’em.’”

Private Pompey Factor

Bullis could count on his men in an emergency, and on April 25, 1875, he had an emergency. Bullis, Sergeant John Ward, trumpeter Isaac Payne, and Private Pompey Factor attacked twenty-five Comanche rustlers who were guiding stolen horses across the Pecos River at Eagles’ Nest. After the scouts twice separated the Comanches from their horses, the Indians regrouped and bore down on Bullis, who had fallen from his horse. “We can’t leave the lieutenant, boys,” shouted Sergeant Ward, and the three raced back. “I… just saved my hair by jumping on my Sergeant’s horse, back of him,” Bullis later wrote. Bullets whizzing around them, the four miraculously escaped unscathed. Bullis saw that Payne, Ward, and Factor were awarded Medals of Honor.

Mary and Fay July at Brackettville, Texas

A Seminole family outside their home in Brackettville, Texas

By this time Chief Horse and his Seminole Nation had found that U.S. government promises of land and food were would not be kept. Rations to families were sharply reduced. U.S. agencies denied responsibility for the treaty that brought the Seminoles to Texas. Generals Augur, Bliss, and Sheridan and Lieutenant Bullis supported Seminole petitions for relief, land, and fair treatment, but to no avail. Federal indifference and stark hunger soon turned families into scavengers and thieves.

The notorious King Fisher outlaw gang, furious at armed Black soldiers in Texas, tried to assassinate Chief Horse and drive his people off. For safety, the Seminoles were moved to Fort Clark, but Fisher’s outlaws were unrelenting. In 1876 John Horse narrowly escaped death in an ambush that killed scout Titus Payne. The Seminole Nation suffered a near fatal blow during their New Year’s Eve dance in 1877, when a Texas sheriff and his deputy arrived to arrest Adam Paine, the fourth Medal of Honor recipient. Instead of arresting him, the sheriff blasted Payne from behind with his shotgun at such close range that his clothes caught fire. At this point Pompey Factor led four other scouts to the Rio Grande, where they washed the dust of Texas from their horses’ hooves and rode back to Mexico.

In 1882 Chief Horse, still seeking a home, land, and refuge for his people, left for Mexico, where he died in a hospital. The scouting unit began to disintegrate and finally was disbanded in 1914. The Seminole Negro Indian Scouts could survive ferocious desert warfare and many enemies but not the unyielding racism of Texas.

A 1914 picture of the Seminole Negro Indian Scouts

In 1842 Martha Williams, an enslaved woman married to a free man of color, gave birth to their daughter Cathay near Independence, Missouri. Cathay Williams, destined for action, was compelled to work for Union troops during the Civil War, and witnessed a land battle and another at sea.

On November 15, 1866, Cathay Williams was seeking excitement. “I wanted to make my own living and not be dependent on relations with friends.” She dressed in men’s clothing and enlisted as William Cathay in Captain Charles E. Clarke’s Company A, Thirty-Eighth Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops. The army conducted no medical examinations, so her military records describe a five-foot-nine-inch man. Her uniform was loose enough to hide her identity; two men in the company – a cousin and a good friend – knew and kept her secret.

Williams’s fellow soldiers included many criminals. “About half of them had been in the penitentiary,” a court investigation later found. Though she had to be treated for smallpox in an East St. Louis hospital, Williams returned to her company in New Mexico, and later served in Kansas. “I was never put in the guard house, no bayonet was ever put to my back. I carried my musket and did guard duty, and other duties while in the army,” she proudly told the St. Louis Daily Times on January 2, 1876.

After two years of service Williams was ready to return to civilian life. “I played sick, complained of pains in my side, and rheumatism in my knees. The post surgeon found out I was a woman and I got my discharge. The men all wanted to get rid of me after they found out I was a woman.”

Williams’ discharge papers also carried an odd and unsupported evaluation but did not mention that she was a woman and being discharged for that reason: “He was then, and has been since, feeble both physically and mentally, and much of the time is unfit for duty.”

The evidence about Cathay Williams is undisputed on one salient point: a courageous Texas African American woman had blazed a new path in the annals of the U.S. Army. A century ahead of her time, she emerged from the buffalo soldiers to tell her tale.

Cathy Williams tills her own Texas farm. (Only known photograph of Williams)