At noon on April 22, 1889, an agitated mob of 100,000 men, women, and children, including an estimated 10,000 African Americans, braced themselves for the gunshot that would open two million acres of Indian land to settlement. Overheated claim seekers made a frenetic stampede by foot, horse, bicycle, and cart that flooded the area. Some ten thousand people turned Oklahoma City into a tent city, and fifteen thousand did the same in Guthrie. By the following morning businesses opened in both cities.

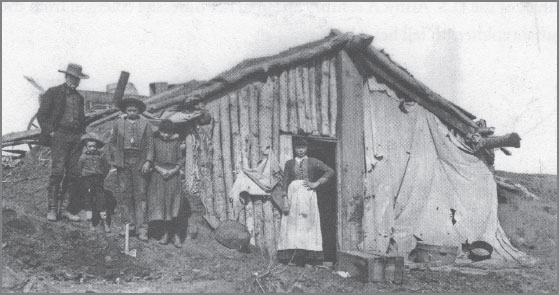

A Black family and their dugout home in Guthrie

Each time Congress opened additional Indian lands for settlement in 1891, 1892, and 1893, African Americans were at the starting line. In 1907 Oklahoma became a state, and its African American population stood at 137,000.

Most of these newcomers were fleeing white violence in the Southern states. In his letter of July 22, 1891, to the American Colonization Society, A. G. Belton captured a people’s desperation in one run-on sentence: “We as a people are oppressed and disfranchised we are still working hard and our rights taken from us times are hard and getting harder every year we as a people believe that Africa is the place but to get from under bondage we are thinking of Oklahoma as this is our nearest place of safety.”

To the oppressed, Oklahoma offered hope and a haven. Edwin P. McCabe, a former state auditor of Kansas, arrived in early 1890 with a wider vision. “I expect to have a Negro population of over 100,000 within two years in Oklahoma.” From Langston City, which he founded in October 1890, McCabe dispatched agents into the South armed with railroad tickets and brochures. His was a mission that mixed rescue, commerce, and nation-building: “We will have a Negro state governed by Negroes.”

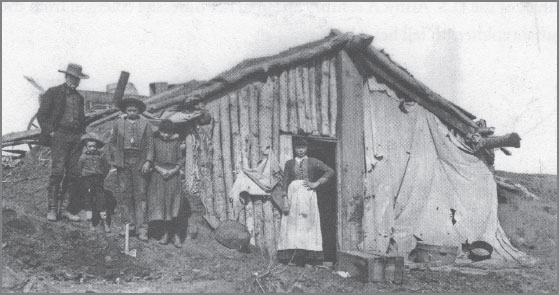

Oklahoma pioneers – the Sutton family – pose for a studio portrait.

In many instances, a hundred or more people from a single Southern community traveled to Oklahoma together. This provided benefits during and beyond the journey. Loved ones and neighbors united in a common purpose marched across the prairies. Upon arrival, familiar faces assured a minimum of friction. Further, with merchants, skilled workers, professionals, and other key workers in their party, community life could start within days. This unified approach also surrounded women with strong family and support networks during the voyage and at the trail’s end.

Langston City’s Roman Catholic Church

Between 1890 and 1910, thirty-two self-governing African American towns sprouted in Oklahoma. Their most common building was a “shot-gun house,” traceable to seventeenth-century West Africa. One room wide, two or three rooms deep, its oblong shape meant a shotgun fired through the front door would pass through without hitting anything and exit the back door. It did not look like much, but it was a better home than people had left in the South.

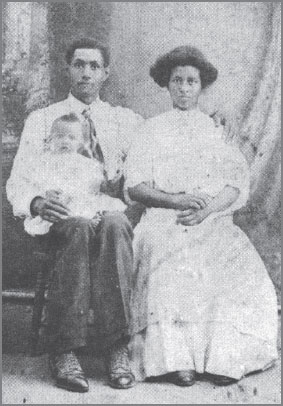

Music class in early Oklahoma

Langston City, Oklahoma’s first Black town, was founded by Edwin McCabe in October 1890 and reached out to hardworking families imbued with middle-class values. Its Herald newspaper reached four thousand readers, its town fathers outlawed prostitution and gambling, and residents could boast their community had no serious crimes. Its streets were named after Black political heroes of the Reconstruction era, and its main avenues were Commercial and Lincoln. The Herald began 1892 by estimating the total value of Black-owned property in Oklahoma at between $250,000 and $400,000.

That year Langston’s mothers and fathers decided their civic priority would be to turn their community of two thousand into the educational heart of Black Oklahoma. They started a tax-supported public school for elementary grades, then a high school for all “regardless of race, color or number.”

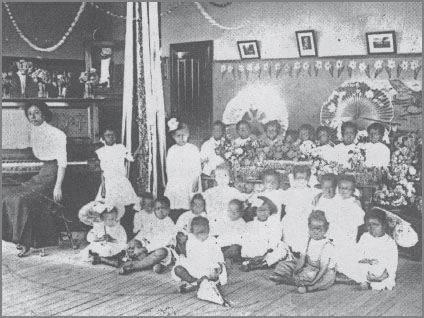

School scene in early Oklahoma

For some time, every few days the Santa Fe train from Texas would pull in a couple of coaches of some southern railroad loaded to the roof with Negro immigrants, Langston bound. They brought their families and their household goods. It was really something to see. Some even came in wagons and lots on foot. Lots of people who came here were so disappointed that they went back home. It took real enterprising folks to stick it out. There wasn’t but one building in town so most of the families lived in tents while houses were being built for them.

Quoted in Mozell C. Hill, Journal of Negro History, vol. 21 (July 1946)

Mozell C. Hill, who grew up in Langston City, wrote of his town: “The titles to these lots could never pass to any white man, and upon them no white man could ever reside or conduct a business according to the literature of the promoting company.”

Langston’s fascinating story is preserved in copies of the Langston City Herald, which McCabe and its editors used to promote their economic investment and political dream. Though desperate to attract settlers, each edition cautioned “COME PREPARED OR NOT AT ALL.” Each issue reprinted the government rules for filing land claims. On its front page headlines blared

FREEDOM!

PEACE, HAPPINESS AND PROSPERITY

DO YOU WANT ALL THESE?

THEN CAST YOUR LOT WITH US & MAKE YOUR HOME IN LANGSTON CITY

The Herald was inspirational, gossipy, and opinionated, and it carried the motto “Without fear, favor, or prejudice, we are for the right, and ask no quarter save justice.” It strenuously opposed “lynch law,” Democratic Party candidates, and discrimination. It praised crusading journalist Ida B. Wells, who visited the town and was favorably impressed, and published a letter from Frederick Douglass who called McCabe a “brave and much needed pioneer.”

The Prairie Center School in Oklahoma and teacher M. E. Porter (right)

By 1897 Oklahoma’s territorial legislature voted the town a grant of forty acres for Langston College. The new college stabilized the community. In 1957 it had 1,250 students.

By 1900 Langston City boasted one of the highest literacy rate on the frontier: 72 percent of its residents could read and 70 percent could write. For Langston’s women between fifteen and forty-five, these figures soared to 96 percent and 95 percent.

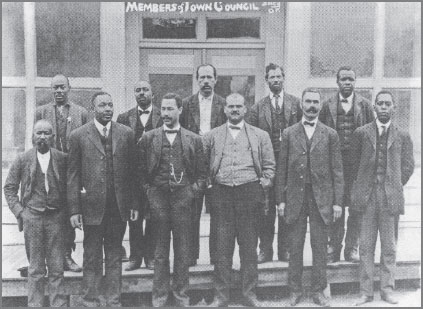

Boley’s town council with mayor (front row, fourth from left) and sheriff (back row, left)

A Boley bank

Boley, like most African American towns in Oklahoma, was carved out of the Indian Territory around Muskogee. Founded in 1904 by Abigail Barnett, a young Black Choctaw woman, on eighty acres, its four thousand residents made it the largest Black town in the West. Boley’s boosters had a lot to be proud of: it had the tallest building between Oklahoma City and Okmulgee, half of its high school students went on to college, and Black men ran the government.

Boley began with a breach of the peace. Dick Shaver, its first city marshal, rode out to arrest Dick Simmons, a white horse thief with a $500 reward on his head. Simmons, who had threated to kill the marshal, fired two shots from his Winchester and one ripped into Shaver’s stomach. As he tumbled from his horse, Shaver fired three shots and each bullet hit Simmons. Both men died. The Boley town council selected another Black man as marshal. Since only Black people ruled the town, they had no intention of turning over the vital matter of law and order to someone who did not care about their lives. For the next two years the new marshal did not have to fire his gun or make an arrest. Peace reigned in Boley.

Though early pioneers arrived to primitive living conditions and dusty streets, Boley grew quickly. In a few years it had 150 children in school, four church congregations with their own buildings, a women’s club, the Union Literary Society, the Odd Fellows Hall, a grocery, a drugstore, a hardware store, a hotel, a sawmill, and a cotton gin. When Oklahoma was admitted to the Union, Boley boasted eight hundred residents and another two thousand lived on nearby farms.

The Creek Seminole College in Boley

Citizens of Boley often struck an independent note. For example, when its Union Literary Society debated whether residents should “celebrate George Washington’s birthday,” the negative carried. The Boley Progress exhorted prospective migrants to strive for the best: “What are you waiting for? If we do not look out for our own welfare, who is going to do so for us? Are you always going to depend upon the white race to control your affairs for you? Some of our people have had their affairs looked after by the white man for the past thirty years and where are they today? They are on the farms and plantations of the white men… with everything mortgaged so that they cannot get away and forever will be so long as they are working upon their farms and trading in their stores.”

Boley’s resident poet, Uncle Jesse, strummed an old guitar and sang of his noble town:

Say, have you heard the story,

Of a little colored town,

Way over in the Nation

On such a lovely sloping ground?

With as pretty little houses

As you ever chanced to meet,

With not a thing but colored folks

A-standing in the streets?

Oh, ’tis a pretty country

With not a single white man here

To tell us what to do – in Boley.

U.S. deputy marshals serving Judge Isaac Parker at Fort Smith. Left to right: Amos Maytubey, Luke Miller, Neely Factor, and Bob L. Fortune.

The forces of white supremacy mobilized to end McCabe’s dream. In 1891 mobs ordered African Americans at gunpoint out of several Oklahoma communities. Even as Black families poured into Oklahoma, earlier residents formed Africa Societies and prepared to leave.

Responding to the speeches and writings of Bishop Turner, who advocated an exodus to Africa, and the American Colonization Society, some Black Oklahoma families sold their land for a fraction of its value and camped in vigils near railroad stations for trains that would carry them to New York City and ships bound for Africa. Some two hundred penniless Oklahomans were housed at a Methodist Mission in Brooklyn. They were joined by another contingent of men, women, and children from Arkansas. Under the sharecropping system, explained one, “We jest make enough to keep in debt.” In 1895 Bishop Turner probably spoke for many of his people in Oklahoma and elsewhere: “There is no manhood future in the United States for the Negro. He may eke out an existence for generations to come, but he can never be a man – full, symmetrical and undwarfed.”

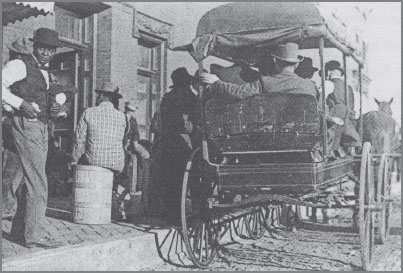

Street scene in Muskogee when the U.S. Dawes Commission came to settle Indian claims

African American families left Arkansas and Oklahoma for New York and ships that would take them to Liberia. Refugees rest in a Brooklyn baptist church. (Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 24, 1880)

There [Guthrie] we saw more colored people than we have ever seen in a northern city. It seems as if a third of the people were colored. We saw colored merchants and lawyers and in almost every capacity, except banking… Every train brought a number of new ones while very few were going back…

[In Langston City] we saw the largest school house in the territory, 6 businesses, mill and gin in course construction, and two churches. There seemed to be about 200 children in attendance at the schools…

I would say to every colored man who has no home try and get one in this country…

Now in order to show sincerity in what I have written, I shall practice what I preach and will locate in the beautiful Oklahoma.

W. A. Price in the Langston City Herald, March 19, 1892

In the 1890s African Americans were among those who laid railroad tracks across Oklahoma.

As Oklahoma moved toward statehood, African Americans, mobilized in the Suffrage League, Equal Rights League, and Negro Protective League, hoped to send their representatives to the U.S. Congress and influence new state government. But African Americans were outnumbered, enjoyed little white support, and did not build alliances with disfranchised Native American residents.

Creek council

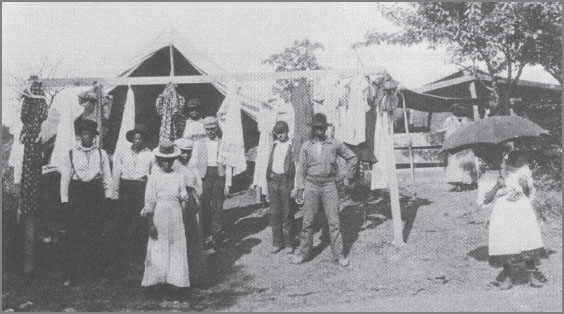

Choctaw friends in Oklahoma

Indians of Oklahoma, including thousands of African Americans, also struggled to survive. Former slaves in each nation had gained their freedom, but fought to win political equality and education for their children. However, few African Americans left their ancestral homes, for they were aware of what awaited them in white society. Many African Americans who came to Oklahoma also chose to live among Native American people.

As Oklahoma lurched toward statehood, Native Americans and newly arrived African Americans inhabited different worlds. Indian communities in Oklahoma derisively referred to the newcomers as “state Negroes.” The Herald did not print negative references to Indians, but neither did it build bridges. When the U.S. Dawes Commission agreed to pay Native Americans for their lands, those members of African descent hired African American attorney James Milton Turner to defend their interests, and after years of legal wrangling he helped them gain $75,000. Turner represented a rare instance of multicultural cooperation in Oklahoma.

At Hayden, Oklahoma Black Cherokees met to receive their awards from the U.S. government.

Enrollment of Choctaws around 1899

As Oklahoma edged toward statehood, the Western Negro Press Association, convening in Muskogee, asked President Theodore Roosevelt to hold off admission until the new state agreed not to pass Jim Crow laws. The president did not respond.

Store at Fort Gibson around 1899

The last Native American uprising – the Crazy Smoke War of 1909 – included Black and Native members.

Oklahoma entered the Union in 1907 as another bastion of white supremacy. It became the first to segregate telephone booths. In 1910 its all-white legislature enacted a “grandfather clause” that disfranchised African Americans because their grandfathers, as slaves, had not voted. Where legality failed, election fraud and night-riding terrorists succeeded in nullifying the African American vote. A refuge and a dream became another Southern nightmare.

At the end of World War II Oklahoma had only nineteen Black towns, and in 1990 the number fell to 13. Only Boley had become a National Historic Landmark.

One of the most enigmatic and shadowy figures in U.S. Western history is Edwin P. McCabe, who first achieved fame when he was twice elected Kansas state auditor. In 1890 he planned to make Oklahoma a home for African Americans, and build a Black state, perhaps with him as governor. He was shot at for his audacity, but he did not relent, risking his life and spending his money to advance his vision.

In 1889 in Guthrie, during the first stampede of settlers, McCabe found a white man who sold him 160 acres forty miles northeast of Oklahoma City. He purchased another 160 acres, set up the McCabe Town Company, and sent agents to recruit settlers in the South. McCabe named Langston City after John Mercer Langston, a Howard University scholar recently elected to Congress from Virginia.

Edwin P. McCabe, Kansas state auditor, 1883–1887

McCabe’s broad plan was to settle a majority of African American voters in each election district so they could shape the new state. Because his goal offered a rare opportunity for African Americans to demonstrate citizenship rights and economic skills, the African American press gave it full coverage.

Attired in his impeccable three-piece suit, McCabe was confident and optimistic. His successful Kansas career had been based on persuasiveness with white political figures. In Oklahoma, he started with an African American population of more than 100,000 as a base to forge political coalitions. Oklahoma would prove African Americans adept at managing economic affairs and a progressive, republican government.

African Americans in the first parade to celebrate the 1889 opening of Oklahoma land to non-Indian settlement

Four Black cowhands join others in an Oklahoma saloon around 1900. Behind outstretched white hand in center are two puppets, one white and one Black.

Named deputy auditor of the Oklahoma Territory, McCabe quickly became a lightning rod for white fury. The Kansas City Star described white people who “almost foam at the mouth when McCabe’s name is suggested for Governor.” The New York Times reported from Oklahoma that McCabe might be “assassinated within a week” and quoted a white man who said, “I would not give five cents for his life.” When McCabe mobilized Black citizens for a September 1891 land rush, he was fired on by three whites, and had to be rescued by African Americans armed with Winchesters.

Teachers and their male principal at Guthrie, Oklahoma

Cherokee Teachers Institute, 1890

Once the icy hand of white supremacy gripped the new state of Oklahoma, McCabe sold his house and left for the East. But he was not finished. Three months after statehood he initiated a lawsuit to challenge Oklahoma’s right to segregate railroad passengers. Perhaps he believed a court victory would end segregation in the state or in the country. For seven years his case wound through the judicial system, but he lost again and again. In 1914 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against McCabe and reaffirmed that segregation was legal in Oklahoma and the nation.

McCabe and his wife lived in Chicago, where at seventy he died in poverty. Despite uncommon business and political acumen and a tenacious courage, he ultimately failed to rescue his people or become governor. But to a people only a generation from slavery, he helped bring the imperishable gifts of pride, self-reliance, and educational opportunity.