In 1898 the United States defeated Spain in what Secretary of State John Hay called “a splendid little war” of ten weeks. Though the announced goal was to “free Cuba,” President McKinley later admitted to wider goals: “We must keep all we get; when the war is over we must keep all we want.” The United States began not to free but to occupy Spain’s former possessions from Puerto Rico in the Caribbean to the Philippines in the Pacific. By 1902 it governed a vast empire of dark-skinned people, and each step of the way to the new colonial empire, buffalo soldiers and other African Americans played crucial roles.

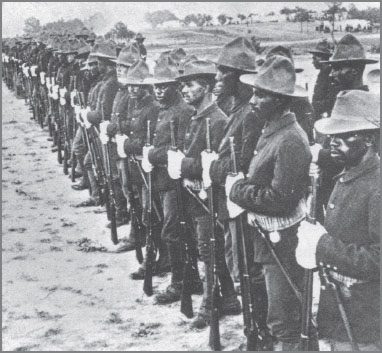

This 1899 photo from the Library of Congress bore the caption “Some of our brave colored boys who helped face Cuba.”

Sergeant Horace Bivins wrote of African American military heroism in Cuba in his Under Fire with the Tenth U.S. Cavalry.

From the outset, the U.S. march into the twentieth century was marked by bigotry at home and abroad. The day Congress declared war, Missouri Congressman David A. De Armond called African Americans “almost too ignorant to eat, scarcely wise enough to breathe, mere existing human machines.” Senator Albert Beveridge, imperialism’s leading U.S. advocate, justified U.S. overseas rule by referring to those in the new colonies as “children… not capable of self-government.” Beveridge and McKinley promised to bring “Christianity” and “civilization” to these new children.

When an explosion sunk the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, 22 African American sailors were among the 250 men who lost their lives. U.S. troop mobilization included the Ninth Cavalry from the Department of the Platte; the Tenth from Fort Assiniboine, Montana; the Twenty-Fourth Infantry from Fort Douglas, Salt Lake City, Utah; and the Twenty-Fifth from Missoula, Montana. As the Twenty-fifth rolled across the continent by rail toward Tampa, Florida, Sergeant Frank W. Pullen reported: “At every station there was a throng of people who cheered as we passed. Everywhere the Stars and Stripes could be seen. Everybody had caught the war fever.”

Then the Twenty-Fifth entered the Southern states. “There was no enthusiasm nor Stars and Stripes in Georgia,” reported Pullen.

The Twenty-Fourth Infantry in Cuba, 1898

In Tampa, Florida, local lawmen and civilians attacked buffalo soldiers. The Richmond Planet commented, “It would have been far better [for Black soldiers] to have been sent to the guardhouse than to Cuba. If colored men cannot live for their country, let white men die for it.”

Before they left for Cuba, aboard the U.S. government transport ship Concho docked at Tampa, the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Regiment was segregated from the white Fourteenth Infantry, who “came and went as they pleased,” reported Pullen. Men of the Twenty-Fifth were confined to the lower deck, “where there was no light, except the small portholes,” and the heat “was almost unendurable.” When the Concho sailed, he noted, “orders were issued providing that black and white troops should not mix.”

The highlight of the short war was the successful U.S. assault at San Juan Hill, Cuba, which propelled Rough Rider Teddy Roosevelt to the White House. Walter Millis’s classic account of the war, The Martial Spirit, described the dramatic moment when “Mr. Roosevelt, with his followers at his back, swept down, splashed through the lagoon and gained the opposite height.” They found, Millis noted, “some of the Tenth Cavalry who had got up before them.” Roosevelt’s version was unstinting in its praise for the buffalo soldiers: “We went up absolutely intermingled, so that no one could tell whether it was the Rough Riders or the men of the 9th who came forward with greater courage to offer their lives in the service of their country… I don’t think any rough rider will ever forget the tie that binds us to the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry.”

The action of the white police officer at Key West, Florida, in ordering Sergeant Williams of the 25th United States Infantry to put up his revolver, is without a parallel in the history of any nation…

We noted with undisguised admiration and satisfaction the action of the twenty-five colored soldiers who repaired to the City Hall and demanded the surrender of their officer at the point of the bayonet, and gave the sheriff just five minutes in which to comply with this demand…

We trust to see colored men assert their rights. If the government cannot protect its troops against insult and false imprisonment, let the troops decline to protect the government against insult and foreign invasion.

Editorial, Richmond Planet, April 30, 1898

Rough Rider Frank Knox, later secretary of war during World War II, joined a unit of the Tenth that day, and recalled, “in justice to the colored race I must say that I never saw braver men anywhere. Some of these who rushed up the hill will live in my memory forever.” The tough, unemotional, Lieutenant John J. Pershing of the Tenth wrote: “We officers of the Tenth Cavalry could have taken our black heroes in our arms.”

As the brief war to save Cuba became a long battle to seize and control overseas colonies, most African Americans viewed imperialism through their own experience. Bishop Henry M. Turner scoffed at U.S. claims of humanitarianism as “too ridiculous,” and predicted that “all the deviltry of this country would be carried into Cuba the moment the United States got there.” “I don’t think there is a single colored man, out of office or out of the insane asylum, who favors the so-called expansion policy,” said Howard University professor Kelley Miller.

Troup C, Ninth Cavalry, charges San Juan Hill. Painting by Fletcher C. Ransome

In the Philippines the U.S. first supported independence and General Emilio Aguinaldo, who had been leading his freedom-fighting army of 40,000 against Spain for years. Then McKinley ordered 70,000 troops, including 6,000 African Americans, to occupy the islands. After they kept Aguinaldo from marching into Manila, a full-scale war began. Almost the entire African American press favored Aguinaldo’s Insurrectos. “Maybe the Filipinos have caught wind of the way Indians and Negroes have been Christianized and civilized,” wrote Salt Lake City’s Broad Ax.

To pacify the Philippines, U.S. troops were issued orders to destroy civilian villages and turn the islands, in the words of Marine Brigadier General Jacob Smith, into “a howling wilderness.” General Robert Hughes, commander in Manila, told the U.S. Senate: “The women and children are part of the family and where you wish to inflict punishment you can punish the man probably worse in that way than in any other.” Asked if this was “civilized warfare,” he responded, “these people are not civilized.”

Ninth Cavalrymen come ashore in Hawaii as part of the first U.S. overseas empire.

This was the first war, historian Gail Buckley has pointed out, in which “American officers and troops were officially charged with what we would now call war crimes.” In forty-four military trials, all of which ended in convictions, “sentences, almost invariably, were light.” A leading voice opposing the war was Mark Twain, who suggested a new Philippine flag: “We can have our usual flag, with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and crossbones.” Bishop Henry Turner, speaking for rising African American opposition to imperialism, said of the African American soldiers “fighting to subjugate a people of their own color,” “I can scarcely keep from saying that I hope the Filipinos will wipe such soldiers from the face of the earth.”

Buffalo soldiers arrived in the Philippines to find people who were not hostile. General Robert Hughes reported: “The darkey troops… sent to Samar mixed with the natives at once. Whenever they came together they became great friends. When I withdrew the darkey company from Santa Rita I was told that the natives even shed tears or their going away.”

But Black soldiers had entered another conflict rich in ironies. They heard white officers instruct their soldiers, “the Filipinos were ‘niggers,’ no better than the Indians, and were to be treated as such.” A white private wrote home: “The weather is intensely hot, and we are all tired, dirty and hungry, so we have to kill niggers whenever we have a chance, to get even for all our trouble.”

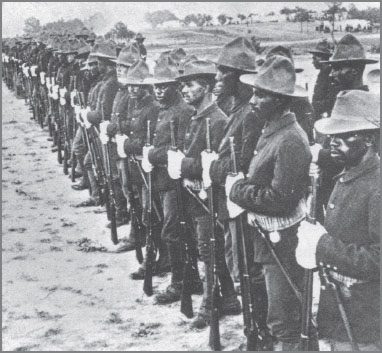

The first Spanish prisoners of the war were captured by the Black Twenty-fifth Infantry regiment, who are shown guarding them in Miami, Florida, in a rare photograph taken on May 4, 1898.

Black soldiers, ordered into battle against a foe whose cause they believed just, wrote home to African American newspapers. Trooper Robert L. Campbell insisted “these people are right and we are wrong and terribly wrong,” and said he would not serve as a soldier because no man “who has any humanity about him at all would desire to fight against such a cause as this.” Private William Fullbright said the United States was conducting “a gigantic scheme of robbery and oppression.” “The whites have begun to establish their diabolical race hatred in all its home rancor… even endeavoring to propagate the phobia among the Spaniards and Filipinos so as to be sure of the foundation of their supremacy when the civil rule is established,” wrote soldier John Galloway.

Words soon led to action. A larger percentage of buffalo soldiers defected and joined the insurgents than white troops. Half a dozen members of the famed Ninth Cavalry and six other African Americans were among the twenty U.S. soldiers who joined Aguinaldo. Washington officials saw David Fagen as the most notorious, though he had been a model solider who had served with the Twenty-Fourth Infantry in Idaho and had won promotion to corporal.

Soon after Fagen’s arrival on the islands in July 1899, he witnessed U.S. atrocities against civilians and was discriminated against by his white officers. A Black noncommissioned officer from his company reported, “From the treatment he got I don’t blame him for clearing out.”

When Fagen marched with General Lawton’s army into Northern Luzon, he probably read Aguinaldo’s famous broadside appeal to African Americans in the army of occupation:

To the Colored American Soldier:

It is without honor that you are spilling your costly blood. Your masters have thrown you into the most iniquitous fight with double purpose to make you instrument of their ambition and also your hard work will soon make the extinction of your race. Your friends, the Filipinos, give you this good warning. You must consider your situation and your history…

On November 17, 1899, Fagen defected with the help of a rebel officer. Historian Frank Schubert has concluded: “He was exposed and probably influenced by the indignation expressed by Negro journalists and fellow Negro soldiers over America’s imperialistic adventures in the Philippines.”

Granted a commission by rebel General Lacuna, Fagen was warmly referred to by the Filipinos he led as “General.” With the slogan “This is our struggle,” he also urged fellow African Americans to join the Insurrectos. U.S. General Frederick Funston considered him a wily foe and offered a $600 reward for him dead or alive. The Manila Times condemned Fagen as “a vile traitor” deserving “the most severe punishment.”

In the next year and a half David Fagen deftly hurled his troops eight times against U.S. forces, not relenting until the spring of 1901, when Filipino resistance collapsed. By then he had married a Filipino woman, and the couple disappeared. The U.S. Army once announced Fagen had been slain by a Filipino hunter, but the army’s internal records cast grave doubts on this claim. More than a few people reported seeing Fagen and his wife living peacefully in a remote village.

A few months after Rough Rider Teddy Roosevelt returned from the war, he rode to victory as governor of New York. Two days later, in Wilmington, North Carolina, white mobs attacked African Americans, including war veterans, in a violent effort to drive Black voters and office-holders from the city. The “Wilmington Riot” became the first in a quarter century of coordinated daylight mob assaults on African American neighborhoods.

March 25, 1899

And we do not blame Aguinaldo and his forces for resisting every effort to be subjugated by the American troops or forces.

…this government has launched upon a career of murder and robbery; and every native who is shot down in cold blood, like common dogs, is conclusive proof that the only object in waging the war against Spain was to acquire new territory by unlawful means.

…What right has it to foully murder innocent women and children? Is this civilization? …This war is simply being waged to satisfy the robbers, murderers, and unscrupulous monopolists who are ever crying for more blood!

May 16, 1899

The chief reasons why we are opposed to the war which is being waged upon the inhabitants of those islands are that whenever the soldiers send letters home to their relatives and parents they all breathe an utter contempt “for the niggers which they are engaged in slaying”…

In view of these facts, no negro possessing any race pride can enter heartily into the prosecution of the war against the Filipinos, and all enlightened negroes must necessarily arrive at the conclusion that the war is being waged solely for greed and gold and not in the interest of suffering humanity.

The Broad Ax, Salt Lake City, Utah

Senator “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, who often justified lynchings before his Senate colleagues, now rose to speak about the war being conducted in the Philippines: “No Republican leader, not even Governor Roosevelt, will now dare wave the bloody shirt and preach a crusade against the South’s treatment of the Negro. The North has a bloody shirt of its own. Many thousands of them have been made into shrouds for murdered Filipinos, done to death because they were fighting for liberty.”

In 1901 Roosevelt was sworn in as vice president of the United States. Two weeks later the capture of Aguinaldo ended armed Filipino resistance. Less than six months later the assassination of President McKinley brought the brash young Rough Rider to the White House.

General Pershing (left) and his expedition to Mexico included Colonel Charles Young (right).

In 1899 buffalo soldiers returned to the United States to find their sacrifice meant little in peacetime. Tenth Cavalry troops on a train bringing war veterans from Alabama to Texas were fired on in Meridian, Mississippi, and in Harlem, Texas. In Rio Grande City, Texas, whites brandished guns and taunted Ninth Cavalrymen until the troopers opened fire and drove them off. The Twenty-Fourth Infantry Regiment returned from Cuba to its base near Salt Lake City, Utah. They were changed men. When their Douglass Memorial Literary Society debated the topic, “Resolved, that there is no future for the negro in the United States,” the affirmative won.

As racist violence intensified for African American citizens, Roosevelt changed his mind about the Black heroism he saw at San Juan Hill. Now he said the buffalo soldiers were “peculiarly dependent upon their white officers.” He now claimed they “began to get a little uneasy and to drift to the rear” so he had to draw his revolver to prevent their flight.

President Roosevelt entered the war over race at home. In 1906, members of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry returned to Brownsville, Texas, to find signs barring them from parks, stores, and bars. When shots were fired in town one night, the infantrymen seized arms and prepared to defend themselves. Though none of their weapons had been fired, and none of the bullets recovered in town came from Aarmy rifles, 167 soldiers in three companies of the Twenty-Fifth were charged with a violent assault on whites. When each soldier denied knowledge of any attack, the 167 were accused of shielding the guilty and dishonorably discharged. President Roosevelt even insisted that at least some were “bloody butchers.” In 1972 a congressional investigation exonerated the 167 men, changed their discharges to honorable, and awarded the sole survivor, eighty-seven-year-old Dorsie Willis, $25,000.

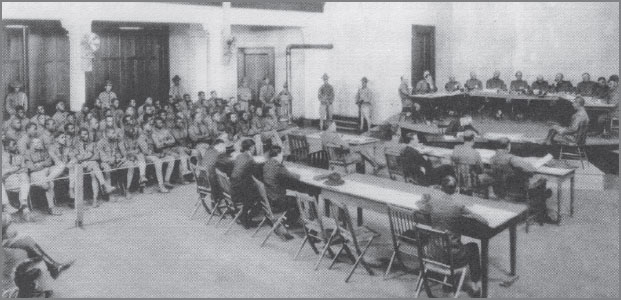

November 1917 trial of 64 members of the Twenty-Fourth U.S. Infantry for murder

In 1917, four months after the nation entered World War I to “make the world safe for democracy,” Houston, Texas, exploded in violence after soldiers of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry were repeatedly harassed by civilians and beaten and jailed by lawmen. Shouting “To hell with going to France, get to work right here,” they surged into town and opened fire. Sixteen whites, including five policemen, and four Black soldiers died in the gunfight. One Army court-martial sentenced thirteen men to death and forty-one to prison for life, and another sentenced sixteen to death and twelve to life in prison.

War Department officials used the Houston riot to inflict a mortal blow on the four buffalo soldier regiments: it forever removed them from combat duty and assigned them to menial tasks. Until World War II, men who had repeatedly shed their blood and demonstrated their patriotism were put to drilling, grooming, and training horses. Never again would distinctive buffalo soldier units fight on a U.S. battlefield.