The story of pioneers of African descent is one of new paths taken, alternative frontiers opened, and untiring efforts to extend the democratic promise of the Founding Fathers. Some of these early pathfinders fled bondage, and, often with Native Americans, became our first freedom fighters. Still others arrived in the West to find restrictions imposed by white settlers; their resistance also turned them into freedom fighters. It is hardly surprising that Native Americans, the first to be enslaved and stung by racial oppression in the New World, often greeted men and women of African descent as allies, and the two peoples soon became family.

Beauty parade in Bonham, Texas, around 1910

“America never was America to me,” wrote Langston Hughes. He lived in a country infected with an ideology that declared the natural inferiority of people of color. Originally conceived to justify those who traded in or profited from the forced labor of men, women, and children of color, this belief soon affected more than slave-ship captains and owners, Indian-hunting armies and slave-hunting posses, plantation masters and overseers. As bondage became entrenched, its rationale became the sine qua non of Southern life, taught to eight million whites from pulpit, schoolroom, newspapers, books, lecture halls, and legal codes. This racist ideology drew its arguments from a spurious science, a twisted history, and selected quotations from the Bible. Its acceptance rested on popularly held European notions about race and a circular reasoning that claimed the enslavement of Africans as proof of inferior status. With its self-serving rhetoric elevating whites over other people, its impact was assured. Whites who dared to challenge the creed of white supremacy risked their reputations, livelihoods, and sometimes life and limb – and stood little chance of influencing others.

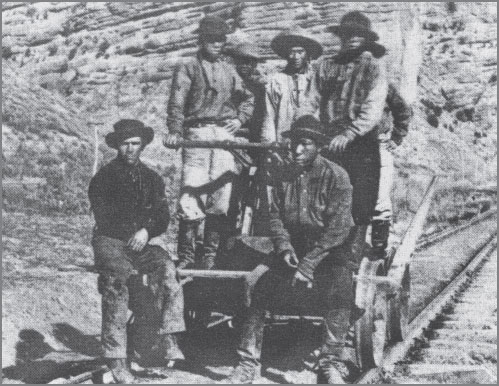

Workers on the Central Pacific Railroad are identified as Chinese – but look at them again.

Bessie Russell holds her baby sister, Lucille, in Floresville, Texas, around 1910.

To expect so fundamental a conviction to be left behind when families gathered their belongings for the voyage westward is to expect too much. White pioneer fears were further inflamed by Indians, who beginning with Columbus had been classified as “primitive.” This became the excuse to seize their lands, enslave their women and children, and burn their villages. Those who announced “The only good Indian is a dead Indian” also dealt with people of African descent.

Whether the European newcomers silently or loudly proclaimed their racial beliefs was a personal matter. But that they chose to carry them into the wilderness, plant them in virgin soil, and cloak them with the majesty of law has been a historical development of the highest consequence. At the moment when slavery lost its foothold in the North and appeared barred from the West, the intolerance it spawned marched westward. The slaveholders who commanded the new federal government breathed new life into their system as the frontier expanded.

The frontier experience furnishes ample proof of the nationalization of racial animosity. The intrepid men and women who crossed the Western plains carried the virus with them, as much a part of their psyche as their great fears and heralded courage. Once established in frontier communities, these hearty souls erected the barriers their forefathers had constructed in the East. As ax-wielding men and women cleared the land; built homes, schools, and churches, and planted crops, their ancient ideas took root. The death of slavery and the final subjugation of Native Americans did not diminish but appeared to elevate national acceptance of white superiority. The hardy pioneers and their children tenaciously clung to the creed of their ancestors.

Students and their teachers at a Black school in the early twentieth century

Black pathfinders soon found they had no hiding place from European racial attitudes and edicts. Even the West’s vaunted antislavery convictions did not stem from moral repulsion to an evil institution, or even calculated white self-interest, but rather from fear of and revulsion toward people of color. By overwhelming majorities, white settlers voted to keep African Americans from voting in elections, testifying in court, serving on juries, and exercising their rights of citizenship. Those who had united to seize Native American lands also agreed to keep people of color from settling in their communities, entering their churches and schools, and receiving justice in their courts.

There were intrepid white pioneers who spoke up for a prospector denied the right to protect claims, a violated woman who had no right to bring her transgressor to justice, or a merchant who was robbed and was kept from testifying against the criminals. Some registered their disgust at the ballot box, or on petitions, or by donating to African American church and school projects. From Ohio to California, white attorneys stepped forward to aid African Americans ensnared in legal nets. Untold numbers of ordinary white men and women pursued a higher law to aid fugitives.

But white officeholders in the West captalized in the white fright that escalated geometrically to arithmetical increases on the Black population. Legislatures passed punitive and restrictive laws against less than a dozen families of color. This reaction to the infinitesimal indicates how racial anxiety and suspicion had outdistanced both reason and simple economic self-interest. It also indicates how deeply psychological an originally economic problem had become. An Underground Railroad ditty composed by fugitive slaves, “Ohio’s Not the Place for Me,” summarized Black reactions to frontier hostility.

Black settlers in the West, few in number, lacking in political power, and helped by few allies, mobilized as best they could. They provided aid and comfort to sisters, brothers, and perfect strangers who fled slavery. They sent representatives to assemble in state and national conventions to air grievances, discuss protest strategies, and petition for their rights. Though short-lived due to lack of readers and capital, crusading pre–Civil War Black papers such as Voice of the Fugitive, The Aliened American, Herald of Freedom, Palladium of Liberty, and Mirror of the Times broadcast community grievances and mobilized support for justice and equality.

Denied basic rights of citizenship, African Americans lacked the civic strength white politicians would heed. A handful of judges acted out of conscience, but officeholders knew it was safe to ignore people who could not vote. At election time white candidates found more was to be gained by denouncing rather than listening to people of color.

A large Texas crowd assembles for a baptism at the San Antonio River in 1914.

John Q. Adams served as editor of The Western Appeal in Minnesota from 1887 until his death in 1922.

During the crisis of the 1850s, Black separatist sentiment became pronounced in the West. In 1854 the country’s largest emigrationist convention assembled in Cleveland, Ohio, its president from Michigan, its first vice president from Indiana, and leading voices from states in the Ohio Valley.

In the age of lynch law that followed the Civil War, the annihilation of Native Americans was not a lesson lost on African Americans. When Ku Klux Klan murders of African Americans mounted in Georgia in 1869 and some advised retaliation, Reverend Charles Ennis sounded this warning: “the whole south would then come against us and kill us off, as the Indians have been killed off.” He knew his enemy.

President Bill Clinton honors surviving buffalo soldiers at the White House.

Between 1880 and 1915, Black Westerners published 43 newspapers, including 16 in Colorado, 15 in California, and 4 in Montana. Begun by highly literate editors with bristling energy and commitment, they sought to educate and advocate for their constituents and advance the battle for equality. A tribute to rising literacy, pride, and sense of community, they sought to unite people, promote community development, and demand respect from white citizens. The Colorado Statesman spoke as the “organ of the colored people of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Utah, and New Mexico.” In 1906 Joseph Bass began the Montana Plaindealer in Helena with a mission of standing up for the right and denouncing the wrong. Bass increasingly exposed prejudice among local and state officials until his paper lost its white advertisers and folded in 1911.

The frontier that beckoned to Black migrants after the Civil War did not become their El Dorado. The “Exodusters of 1879” sought land and opportunity in Kansas and found a respite from Southern violence and a partial freedom. The solitary symbol of their state power, Kansas auditor Edwin P. McCabe, was dropped from his post after two terms. His plan to build a sanctuary and power base for his people in Oklahoma was also overwhelmed.

By the 1890s Black emigrationist sentiment reappeared among Western African Americans as a clear barometer of rising suffering, discontent, and frustration. Hundreds of Black pioneer families from Arkansas and Oklahoma said they were ready to board the first ship to Africa. If the frontier proved a “safety valve” for white discontents, as historian Frederick Jackson Turner claimed, it rarely proved so for people of color. It provided an escape from systematic violence and a respite from the more intense forms of hatred, but hardly a new America.

With a homogeneous population pouring into the country from Europe, we must secure an equal chance in the race for life now. If this opportunity be lost, all is lost. We must learn to conform to the conditions that surround us. We must learn many new things and forget many old ones… Our boys and girls must be trained to be more ambitious and aspiring and self-dependent. We must be menials and pariahs no longer. We must get an education…

C. L. de Randemie, The Colored Patriot, Topeka, Kansas, April 27, 1882

As the frontier West came to a close, a quarter century of white invasions of African American neighborhoods – called “race riots” by the U.S. media – disrupted major Eastern cities, the earliest in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898. Atlanta, Georgia, experienced several days of a massive mob murder and mayhem in 1906 – similar to European pogroms that drove Jews to leave for the Americas. For people of color in the West, these riots were a stark reminder of the violence they fled. An artist for a popular French newspaper showed how Black people in Atlanta, some with guns and knives, tried to defend their neighborhoods.

However, frontier life emphasized the need for cooperation. Marked by social fluidity, a blurring of class and caste distinctions, and the sharply defined Victorian roles accorded men and women, the frontier offered rare opportunities. North of Oklahoma and west of Texas in particular, and in cowboy trail crews generally, African Americans found few barriers. Frontier dangers called forth interdependence and informal living and working arrangements that undermined divisiveness and challenged segregation.

Kenneth Wiggins Porter’s study finds that while multiracial trail crews endured violence, few shootouts had a racial component. Some cowpunchers – often Confederate veterans – did target people of color, more often Indians and Mexican Americans than Black fellow cowhands. Several Black Indian bands in Oklahoma – the Creek Lighthorsemen (police) in 1878 and the Dick Glass outlaw crew in the early 1880s – raised their rifles, as would California’s latter-day Black Panthers, against those who perpetuated white violence.

Leavenworth’s first electric railway in 1902 drew children of both races.

Racial hatred crossed the bumpy post–Civil War trails in prairie schooners and was dusted off for use in growing frontier towns, particularly after the arrival of white women. The closer Black cowboys rode to town and to its white families and institutions, the more likely they would encounter hostility. Discriminatory patterns sharpened in Western communities with the delivery of Sears Roebuck catalogs, the beginning of public schools, and early meetings of white religious congregations.

Slavery’s sharpest legacy after ingrained racism was a financially devastated community. Though unpaid Black labor nationwide had produced the capital for factories, farms, and ranches, four million people left bondage penniless, unable to buy the extensive farms or sprawling ranches that made economic survival likely. Cowhands rode out their lives as landless horsemen, and only a handful eventually owned a ranch.

Rodeo doors were often closed to Black cowpunchers with extraordinary skills. Many also lacked the cash required by sponsoring associations, or the sociable contacts with rodeo officials that had opened the way for white performers. Until his success with the 101 Ranch Rodeo made him a legend, Bill Pickett had to perform as a “Mexican toreador.”

Women and men in the West resisted oppression in every way they could. Black women swung their umbrellas and men raised their fists at belligerent laws and neighbors. A white man in Texas accused Bill Pickett of stealing a horse and said, “You better hand him over,” shoving him and raising his fist for a haymaker. A Pickett punch sent him rolling and groaning on the ground.

Your west is giving the Negro a better deal than any other section of the country. I cannot attempt to analyze the reasons for this, but the fact remains that there is more opportunity for my race, and less prejudice against it in this section of the country than anywhere else in the United States.

James Weldon Johnson, secretary of the NAACP, Denver Post, June 24, 1925

Some Black residents sued for justice in courts, and others pounded away in letters, petitions, picket lines, and delegations. And there were occasional successes. Petitions, entreaties, and lobbying by determined African Americans in Colorado, led by William J. Hardin, convinced the U.S. Congress in 1868 to extend voting rights to all adult Black males in western territories.

The 1890s – which saw the close of the frontier – was an era of agonizing change in the United States. During the next generation each Southern state, including Texas and Oklahoma, codified segregation, often into state constitutions. In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court in the Plessy case ruled by eight to one that segregation was constitutional. The Populist movement briefly united Southern Black and white farmers against Eastern bankers and merchants, but ended in a bitter defeat that led to more lynchings and an explosion of white violence north and south.

Sutton E. Griggs, crusading writer

During this low point in the fortunes and power of African Americans, their suppressed rage rested close to the surface. The only African American to dedicate a book to a Western state also delivered a highly inflammatory condemnation of his country. Sutton E. Griggs, born in 1872 in Texas and graduated from Bishop College in Marshall, dearly loved both his people and his state. To “Texas soil which fed me, to Texas air which fanned my cheeks, to Texas skies which smiled upon me, to Texas stars which searched my soul, chased out the germs of slumber,” Griggs dedicated a book of essays on race relations. Rarely a man to slumber, Griggs devoted his life to examining the painful world whites created for his people and evaluating different solutions. A Baptist minister who played a prominent part in the national affairs of his church, Griggs, though barely known today, was probably the most widely read novelist among his people, surpassing white favorites Paul Lawrence Dunbar and Charles W. Chesnutt.

In 1899 Griggs published his first novel, Imperium in Imperio, in which conspiratorial Victorian characters engage in a raging revolutionary melodrama. Griggs describes an African American society, the Imperium, that meets underground in Waco, Texas, and plans to unite with foreign enemies of the United States during a war (the Spanish-American War), and seize Texas and Louisiana. A Griggs character states: “Louisiana we will cede to our foreign allies” but “Texas we will retain… Thus will the Negro have an empire of his own.” For more than half a century no one reviewed Grigg’s Imperium in Imperio. Perhaps it was too subversive. That this flaming banner could be unfurled by so loving a son of Texas is a measure of the West’s failure to provide people of color their share of America’s promise.

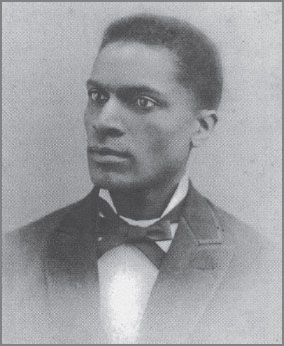

Frederick L. McGhee around 1891

Along with other civil rights proponents, Sutton Griggs joined the Niagara Movement of Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, which demanded full and immediate citizenship rights. Its legal director was Frederick L. McGhee, a former Mississippi slave. According to Du Bois, “the honor of founding the organization belongs to F. L. McGhee, who first suggested it.” An early settler in St. Paul, McGhee was the first Black American admitted to the Minnesota bar. He handled civil rights cases, served Booker T. Washington as a lobbyist with Congress, and became his emissary to Catholic prelates.

Following the war with Spain in 1898, the United States ruled millions of aboriginal peoples on islands from the Caribbean to the Pacific. McGhee’s anguish grew. America might have crushed the Filipino drive for independence but failed to halt racial violence and lynchings at home. McGhee denounced “the spirit of mob rule, the prevalence of lynch law, in all parts of our country.” He linked it to his country’s effort overseas “to rule earth’s inferior races, and if they object make war upon them.” African Americans “should be the loudest in the protestations against the oppression of others.” He concluded: “The Negro cannot, if he would, God forbid that he would if he could, support the present administration in its war on the Filipino.”

Our soldiers wrote home of what fun it was to shoot the “niggers” and see them keel over and die. Then came the famous order, “Take no prisoners,” followed by the shameful account of the fiendish slaughter of forty-six Tagals, because one had killed an American soldier. Of the number of women and children killed in attacks upon villages defended by men armed with bamboo spears, this with the profoundly and oft-repeated assertion, of late so prevalent, that the proud Anglo-Saxon, the Republican party, by divine foreordination, is destined to rule earth’s inferior races, and if they object make war on them, furnishes an all-sufficient cause. Is it to be wondered then that so little value is placed upon the life, liberty, freedom and rights of the American Negro? Is he not also one of the inferior races which Divine Providence has commissioned the Republican party to care for? These things cannot go on with impunity abroad without the same thing cropping out at home…

Frederick L. McGhee, Howard’s American Magazine, October 1900

In 1916 buffalo soldiers leave Mexican soil.

A highly informed understanding undergirded the impatient fury of Sutton E. Griggs of Texas and Frederick L. McGhee of Minnesota – both successful Western professional men, respected community and religious figures. They measured their government in language as broad and clear as the land that stretched from McGhee’s Minnesota to Griggs’s Texas.