While most of this book is focused on the past, since writing it, I’m regularly reminded that the Black West is still a vital and ever-influential part of our national fabric. Take, for example, the tale of J. B. Keeylocko, and the town he built in Arizona after the Vietnam War.

One of the first invitations I received to launch the first edition of The Black West brought me to the University of Arizona at Tuscon. When I landed at the airport, Mr. J. B. Keeylocko was there to greet me. One of the first African American cowboys to own a ranch, he spent years publicizing the story of cowboys who looked like him, and he was there to make sure we would take a photo.

Born in 1931 to Alice Long and a white father, J. B. (sometimes called Ed), was brought up by Esther Brooks, a family friend. He joined the U.S. Army at nineteen, and served in Korea and Vietnam. Stationed in Arizona, he decided to remain there when discharged.

“When you’re a little boy, you dream of all kinds of things,” J. B. told me. “You dream of things that never were, and then you try and do them. People say, ‘How do you dream all these things up?’ I guess it’s just part of my life when you grow up alone.”

And J. B. never stopped dreaming. He enrolled in Pima Community College and at the University of Arizona to study agriculture. Then, in 1976, he bought forty acres of land, with a $1,660 down payment for the $15,800 property. This property, bought to be a ranch, became the basis of something much greater: a town.

In describing how he founded Cowtown Keeylocko, J. B., said, “Two old fellas, tobacco juice running down their lips … One said, ‘You ought to build your own town, and sell your cows in your own town.’ I drove a little bit away, and then I said, ‘What did you say?’ ‘I said, you ought to build your own town, then you wouldn’t have to come up here and complain about nothin’’.’ I said, ‘You know that’s a good idea, I’ll do that. I’ll build my own town.’” He recalled how the two men “laughed right up their sleeves. But nobody laughs today.”

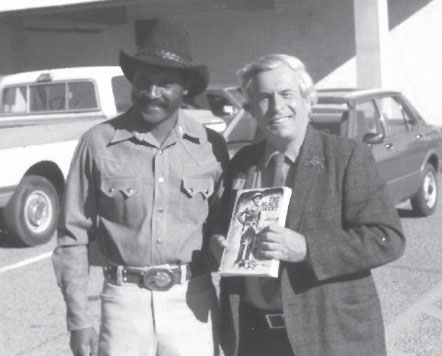

My first meeting with J.B. Keeylocko, at the Tucson airport.

The directions to his town were almost as freewheeling as his decision to build it. To get to Cowtown Keeylocko, J. B. said, “Head west. Watch Kitt Peak, and follow the signs to milepost 146. Cowtown Keeylocko. You see a sign that says three hoops and a holla, then two hoops and a holla, then one hoop and a holla, and then you’ll be right in the town of Keeylocko. We have the coldest beer in Arizona, so cold you have to open the beer with your overcoat on.”

Longtime friend David Beaubien recalled J. B.’s goal. “He wanted to make this basically an open oasis where everyone was welcome.” His Keeylocko Land Feed and Cattle Co., “soon had dozens of cattle, horses, and hogs roaming his land.”

This goal matched J. B.’s desire to live according to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s creed, “I look to a day when people will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

Another friend described how he acted on this belief: “The amount of respect and kindness he gave to everyone who came around, it was just amazing.” Most important, his friend McDowell recalled, J. B. wanted the people of Arizona to know that Black cowboys were commonplace in the old West.

In the end, it was always about staying true to the dream. J. B. always dreamed that the best outcome was possible. “You dream and think. Believe the impossible. Because you can do the impossible. Always stay the course, no matter how hard. Dream of things that never were and ask why not.”

In 2014, nearing the end of his life, he told a documentary filmmaker, “The difficult, I’ll do right away. The impossible, it might take me a few days longer.” He added, “Cowtown Keeylocko is the real, real West. We are the way the West really was.”

In March 2019, J. B. “Ed” Keeylocko died, in the town he built as a living, thriving tribute to the Black West.