Lord of the Flies

PORCHETTA di TESTA

When I was very young—probably seven—the 1963 film version of Lord of the Flies was on television one night. It was Christmastime and I was sitting next to my mom and dad on the couch when my dad, flipping through the channels, stumbled across it and stopped. For the next three hours I sat still as stone, terrified by what I was watching, but too shy to tell my parents.

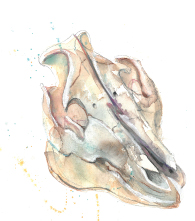

As I lay in bed that night trying to sleep, the image of the fly-covered pig’s head, a stake stuck into its neck, kept going through my tiny stressed-out brain. It’s not as if I had never seen a pig’s head before. I saw them often at my grandfather’s butcher shop, but they were hairless and pale pink, eyes half-shut and mouths curved up in a way that made them look content—they were nothing like that hairy, bulgy-eyed monster from the movie. For the remainder of that night, and for a few nights following, I slept on the floor of my parents’ room.

Years later I was assigned the novel in school and was rattled all over again by William Golding’s account of a group of young English boys stranded on an uninhabited island after a plane wreck. At first, the boys adhere to the laws of social order they have been raised with—calling meetings, electing leaders, dividing labor—but as the novel progresses, this order quickly crumbles and the reader watches, realizing along with Ralph that “the world, that understandable and lawful world, was slipping away.” Golding strands this specific age group—boys between six and twelve years old—because they are particularly susceptible to shedding societal constraints. In showing us how quickly this mini society plunges into chaos, he challenges the notion that humans are inherently civilized.

When the boys first land on the island, their proper English manners and habits are still deeply ingrained. Faced with the prospect of having to kill a pig because everyone is hungry, Jack is unable to follow through, “because of the enormity of the knife descending and cutting into living flesh; because of the unbearable blood.” Only two chapters later, however, Jack slits a pig’s throat and proudly comes back to the camp with the “knowledge that they had outwitted a living thing, imposed their will upon it, taken away its life like a long satisfying drink.”

When the “littluns” start to worry that there is a beast lurking around the island, panic spreads throughout the camp and Jack decides to take the head of the pig they killed and present it as an offering to appease the beast. The pig’s head, which they call the Lord of the Flies, comes to represent chaos and disorder, savagery and the instinctual brutality of human nature (I learned only recently that the literal translation of Beelzebub is “lord of the flies”). The image is so powerful, both in film and in writing, that even now, having de-faced countless pigs’ heads at the Meat Hook, I still think about Lord of the Flies every time I do it.

The truth is, pigs’ heads are absolutely delicious if you are willing to take the time to prepare them the right way. It seems intimidating, but it’s much easier than you would expect.

LORD OF THE FLIES

Porchetta di Testa

Most local butcher shops have pigs’ heads on hand, and if not, they will usually be happy to special-order one for you. For this recipe, ask your butcher to take the meat off the head in one piece and clean it of all the glands. Then all that’s left to do is spice it, tie it up as you would a roast, and cook it. It goes great over a bed of lentils, potatoes, or stewed greens.

Serves 8 to 10

Meat of 1 pig’s head, all in one piece, including ears and tongue, cleaned of all glands (about 7 pounds of meat)

4 tablespoons kosher salt

1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon fennel seeds, toasted

2¼ teaspoons freshly ground black pepper

1½ teaspoons crushed red pepper

Finely chopped leaves of 2 rosemary sprigs

Finely chopped leaves of 2 thyme sprigs

15 garlic cloves, put through a garlic press

Zest of 2 lemons plus 1 tablespoon lemon juice

1 teaspoon plus 2 tablespoons olive oil, divided

First, you’re going to clean the meat up a bit, which includes shaving the outside meat with a razor if there is any hair (come on, it’s fun!). Also make sure that there are no glands, and that the hard collagen from the nostrils and ear canals are cut out—your butcher should have done this for you, but it doesn’t hurt to check. Now, in a large mortar, combine 2 tablespoons of the salt and the rest of the ingredients except the 2 tablespoons oil and mash them up with a pestle until a nice paste forms.

Spread the face meat in front of you, skin-side down. Tuck the ears backward, up through the eyeholes, so that the holes are covered, and flatten them out. Rub the seasoning paste all over the meat. Lay the tongue flat along the inside of the snout and rub it with any remaining seasoning paste.

Starting with the jowl on one side, roll up the meat like a jelly roll. Tie the cylinder tightly with twine as you would a roast, set it in a roasting pan on a roasting rack, and place it in the refrigerator, uncovered, to cure overnight. The next day, take the roast out and let it sit at room temperature for 1½ hours.

Preheat the oven to 450°F.

Rub the outside of the roast with the remaining 2 tablespoons salt and roast for 20 minutes.

Lower the heat to 250°F, cover the roasting pan with aluminum foil, and cook for an additional 2½ hours. Remove the foil and brush the skin with the remaining 2 tablespoons olive oil. Bump up the heat to 325°F and continue to roast for 30 minutes. (This should get the skin crispy.) The roast should reach an internal temperature of 140°F.

Remove the roast from the oven and allow it to rest for 20 minutes before slicing crosswise and serving.