Shopping

In the South, shopping is not just about the acquisition of needed items like groceries and gasoline; it is a recreational sport in which some of the participants can be very competitive. Word of caution: do not attempt to take the last cashmere sweater off the rack at a half-off sale; if you do, you might find yourself minus a limb. Within southern culture, shopping is a form of recreation that crosses class and gender lines, allowing everyone an opportunity to participate. No matter the economic status or gender of the participants, there is always a recreational shopping opportunity available and, in the South, these opportunities are abundant.

Those in an economic position allowing them to spend with impunity can find much satisfaction with the shopping opportunities available in the South. Of course, there are the shops that cross all geographic boundaries such as high-end department and chain stores, but throughout the South the wealthy are more attracted to small boutiques specializing in a wide range of high-priced items, ranging from baby needs and lingerie to books and housewares. Within the artistically painted walls of these specialty shops lie hundreds of items that many would classify as “overpriced” or “pretentious,” but for many recreational shoppers who frequent these establishments, such qualities are precisely what attracts them. Recreational shoppers of the wealthy sort often find satisfaction in purchasing items that are not necessities at prices they know to be inflated. This satisfaction can be attributed to the simple knowledge the purchaser has that they do indeed possess the extra cash (or credit card) to purchase items that others cannot afford. For them, the purchase can represent something greater than merely handing over a debit card and receiving a monogrammed christening gown in exchange; it can tell them something about themselves, something they need to know. While helping to reassure consumers—and others—of their status in society, specialty boutiques offer those with unlimited funds the opportunity to dispose of it, a niche that boutiques, and their owners, are delighted to fill.

For the recreational shopper with a more modest income, there are myriad choices available in the South. Purchasing a single item from a high-end boutique can be quite satisfying, but many recreational shoppers of more modest means prefer quantity over quality. Enter outlet malls. Although not strictly limited to the South, these megacenters of bargains call to the southern recreational shopper with their promises of half-price china and two-for-one socks more so than other regions—a result of the increasingly overwhelming consumer culture that predominates the South. Southerners like “stuff.” They like to have their “stuff” on display in their homes, their driveways, and on their person. Outlet malls allow southerners to obtain “stuff” in great quantities on a single outing in a single location, explaining its unavoidable draw. The discussion of the quantity aspect of outlet malls is not to say that there are not high-end items available at outlet malls. Quite the contrary. Many high-end designers have stores in outlet malls where overstocks and slightly damaged merchandise are sent to be sold at varying degrees of lower price than those same items would be found in a traditional department store or specialty boutique, thus allowing recreational shoppers of limited means the opportunity to own and display luxury goods that they otherwise would not be able to afford.

Another popular option for budget conscious shoppers in the South is the department store, an entity that has added much to the culture of the South throughout the past century. For much of the 20th and 21st centuries, southern department stores such as McRae’s (founded in Mississippi), Stein Mart (Mississippi), Pizitz (Alabama), Belk (North Carolina), Dillard’s (Arkansas), Goldsmith’s (Memphis, Tenn.), Maison Blanche (New Orleans), and Goudchaux’s (Baton Rouge) have helped to fuel the heavy consumerism prominent in the South. Among different department stores there has existed a great range in the quality and prices of goods available. Recreational shoppers of all income levels can find a department store to suit their needs in the South. Offering items ranging from clothing to cosmetics, furniture to fragrances, the department store serves as the foundation for recreational shopping.

Department stores have not only influenced the recreational culture of the consuming public but have also greatly influenced the recreational shopping potential of their employees. Many department stores offer an employee discount that allows employees to purchase goods that they otherwise might not be able to afford. Offering such a discount increases the stores profit margins as well as allowing the employee a chance to shop recreationally. Imagine the possibilities of working in a department store every day, seeing new items arrive, later go on sale, and then choosing just the right moment to make your purchase utilizing the employee discount. What better definition of recreational shopping can be found? For the employee the recreation begins weeks, perhaps months, in advance, watching an item as it moves through the store and eventually onto sale racks, and culminates with the purchase of the item. From this perspective, shopping is truly an important form of recreation for the employee of the department store.

Even though the tendency might be to classify recreational shopping as a singularly female pursuit, in the South this certainly is not the case. Not only do men routinely engage in recreational shopping through the aforementioned avenues, but they also participate in the consumer culture by shopping recreationally at stores designed to cater to a predominantly male customer base. Supersized outdoors stores, such as B.A.S.S. Pro Shop and Edwin Watts Golf, as well as smaller boutique-sized shops, such as independent hunting retailers, cater to a predominantly male clientele by offering items for the outdoorsman, the sportsman, and the athlete, among others. Such stores provide men with the opportunity to participate in the consumer culture typified by recreational shopping within parameters that men can define as separate from the recreational shopping spheres of women. Even though it is clear that certain stores and departments within stores cater to either a male or female clientele, it is also clear that both sexes have ample opportunity in the South to participate in recreational shopping.

In so many small towns, Wal-Mart (another southern store) has become the main retail outlet and therefore the heart of recreational shopping. Like a mall, Wal-Mart has everything under one roof. Shoppers begin arriving before 8:00 A.M. and buy a biscuit and coffee at whichever café is allowed to share that space (once exclusively the domain of McDonald’s, now Subway dominates that market). Women meet friends, men meet friends; they wander, shop, talk, take a coffee break, wander and shop some more, then have lunch where they had breakfast or at a nearby restaurant. It is a community experience.

Throughout the South recreational shoppers have many opportunities to engage in their favorite hobby. From high-end boutiques to outlet malls to department stores, the southern shoppers have the opportunity to find virtually any consumer good they desire at a wide range of prices. For many, the draw of recreational shopping is the hunt—the hunt for the desired good at the lowest price available. In the South, recreational shoppers have more than enough opportunity to indulge their favorite pastime. Whether enjoying shopping on a budget or spending without regard to financial restriction, the recreational shopper in the South is engaging in an incredibly popular pastime available to members of all races, classes, and genders.

ERIN JONES SCHMIDT

University of Alabama

Marianne Conroy, Social Text (Spring 1998); Kuan-Pin Chiang and Ruby Roy Dholakia, Journal of Consumer Psychology 13:1–2 (2003); Pasi Falk and Colin B. Campbell, eds., The Shopping Experience (1997); Robert Prus and Lorne Dawson, Canadian Journal of Sociology (Spring 1991); Edward M. Tauber, Journal of Marketing (October 1972); Sharon Zukin, Point of Purchase: How Shopping Changed American Culture (2004).

Soccer

Within the past 30 years, soccer, which for generations had been eclipsed in popularity within the South by the dominant sports of football, basketball, and baseball, has emerged as an increasingly popular sport. Formally organized in England during the early 19th century, soccer (or football, as it is known outside of the United States) spread dramatically across the globe in the following century, becoming the world’s most popular team-based sport by 1950. In the United States, however, soccer was slow in gaining popularity, owing partially to the game’s late entry into the national sporting culture and lingering perceptions of American isolationism. Within the South, the game’s popularity was even slower in developing. With few European, Asian, or Latin American immigrants arriving to the southeastern states between 1850 and 1950, the growth of soccer was markedly slower in the South than the North or West, where the game thrived in urban immigrant enclaves.

Soccer first established a foothold in the urban South, where amateur leagues began to organize small tournaments in the 1920s and 1930s. By the late 1950s several universities were fielding men’s teams, including Duke, Emory, and the University of North Carolina, which competed against one another in regional conferences. The formation of the North American Soccer League (NASL) in 1968 further boosted the game’s popularity, especially when the Atlanta Chiefs became a leading team in the early 1970s. But it was only with the post-1970 “Sunbelt” boom in suburban development that soccer began to grow at an explosive rate, and it was here that the game attained its enduring reputation as a youth sport. For thousands of northern and western white-collar professionals who moved to the suburbs of cities like Atlanta and Charlotte, soccer was a game they had played as children, a safer alternative to the often-bloody game of football. In affluent suburban communities across the Southeast in the 1980s and 1990s, therefore, soccer would quickly grow to challenge the old trinity of baseball, basketball, and football, and by the turn of the 21st century tens of thousands of southern children were playing regularly in intramural, school-sponsored, and private soccer leagues.

While the expansion of soccer as a suburban youth sport was successful in introducing the game to a wide new audience, equally dramatic was the soccer boom that has accompanied the South’s recent surge in immigration. After a century of relative homogeneity in its white and black population, the Southeast since 1980 has attracted a diverse new wave of immigrants, most notably from Mexico and Central America, China, South Korea, and various West African nations. This unprecedented demographic transformation has wrought tremendous cultural change, and the growth of immigrant soccer leagues is a prominent example. Especially for Latin American immigrants, whose reverence and dedication to the game is legendary, participation in Latino soccer leagues in urban, suburban, and rural settings has become a crucial avenue of recreation, community formation, and even career networking in their newest home.

Such change has not been without conflict or controversy, however, and many Latino newcomers have encountered hostility and resentment from native southerners, in which public recreational spaces often became a key arena of contention. As immigrant soccer leagues grew in popularity and began to compete with traditional southern sports for the use of public space, unsympathetic city and county governments during the 1990s and 2000s initiated campaigns to restrict immigrant access to public parks, and signs proclaiming “NO SOCCER ALLOWED / NO PERMITE EL FÚTBOL” appeared on football fields and baseball diamonds across the South, in both small towns and large cities. For Latin American residents, this symbolic attack on their culture and belonging has engendered considerable bitterness and protest, and while negotiation and compromise have led to solutions in some communities, the conflict over immigrant culture and public space continues to plague much of the South.

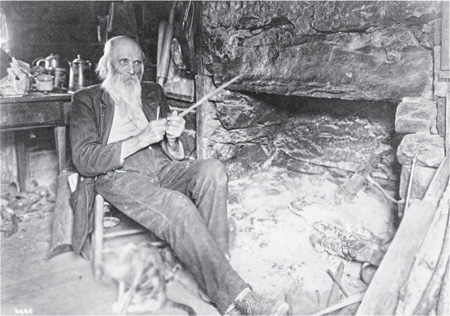

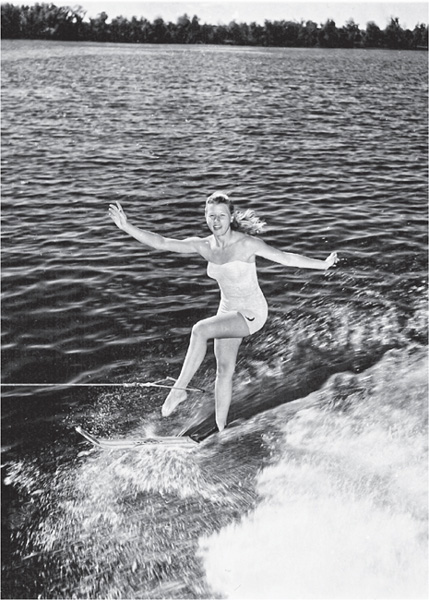

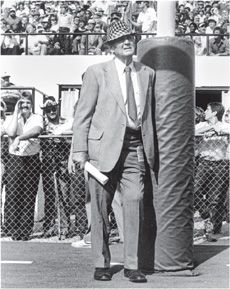

It was not until the 1980s and 1990s that soccer became a popular sport among southern schoolchildren, but the game has been a collegiate sport in the South since the 1950s. (Photograph by Bill Mathews, courtesy of Judson College, Marion, Ala.)

The growth of soccer, therefore, has become symbolic of the enormous transformation of the South since the civil rights movement. Suburban youth teams and Latino immigrant leagues, while playing the same sport, are clearly the products of different phenomena, yet each represents an important trend in recent social and demographic change.

TORE OLSSON

University of Georgia

Marie Price and Courtney Whitworth, Hispanic Spaces, Latino Places, ed. Daniel Arreola (2004); Rory Miller and Liz Crolley, eds., Football in the Americas: Futbol, Futebol, Soccer (2007); Andrei S. Markovits and Steven L. Hellerman, Offside: Soccer and American Exceptionalism in Sport (2001).

Square Dancing

Square dancing has long been a part of the traditional culture of the rural South. Square dances, for groups of four or more couples, have their roots in popular European social dances of the 18th and 19th centuries (French cotillions and quadrilles, English country dances, and Scots-Irish reels); they also show the influence of African American and Native American dances. The earliest detailed account of southern square dancing comes from English folk music and dance scholar Cecil Sharp, who—with his colleague Maud Karpeles—observed dances at several locations in eastern Kentucky in 1917. Sharp interpreted these rural southern dances (which he called “The Running Set”) as survivals of 17th-century English country dances. He mistakenly believed that these old dances had remained intact and unchanged for many generations and that the remoteness of the mountains had kept them free from the contaminating influences of modernity. The southern square dance, however, is a distinctly American dance form, one that did not exist until the 19th century when European social dances merged with elements of African American and Native American dances in the America South.

Before the 20th century, dancing was a common recreation in Anglo-American, African American, and Native American communities. Square dances often accompanied such community work gatherings as corn shuckings, molasses makings, and barn raisings; they also occurred at weddings and other festive occasions, particularly during the Christmas season. Most often held in private homes, such dances also took place in barns, taverns, or even outdoors on the bare ground. By the 1930s, square dances had lost their association with work parties and special occasions and had become public events serving a wider region and held in large community halls on a regular basis throughout the year. While these public dances are now relatively rare, they still happen in some rural communities, with dancers of all ages sometimes traveling several hours to attend on Friday or Saturday nights.

Although the name “square dance” implies a square formation for four couples, southern square dances are often done with any number of couples in a big circle set. Today, the four-couple square is more common in northern West Virginia, Arkansas, and Missouri, while the big circle is the dominant form elsewhere. Southern square dances are characterized by visiting couple figures (where each couple takes a turn leading the figure); a verse-chorus structure (such that the visiting couple figure performed by two couples alternates with a chorus or ending figure involving all of the couples); the presence of distinctive southern dance figures (such as “Bird in the Cage”); fast paced music; and improvisational dance calling that guides the dancers through the figures.

The practice of dance calling appears to have emerged in African American communities in the early 19th century as a way to lead dancers who were not trained in the formal figures of French cotillions and quadrilles through the dances. The first documented dance caller was an African American musician at a formal New Orleans ball in 1819. By the mid-19th century, dance calling had become a common practice throughout the rural South. Such calling was the key element that transformed the earlier European dances into a distinct American dance form, in a process that paralleled the way that the African American banjo transformed European fiddle styles to become southern dance music. Without the African American practice of dance calling, southern square dances would not exist in their present form.

Following World War II, a new form of square dancing, called “Modern Western Square Dancing,” developed from the traditional square dances of the western United States. With standardized dance calls, professional callers, recorded music, and western costumes, this new style of square dancing became popular across the country, competing with and displacing many of the older community-based rural dances. Today, Modern Western Square Dance clubs can be found throughout the South.

PHILIP A. JAMISON

Warren Wilson College

S. Foster Damon, The History of Square Dancing (1957); Philip A. Jamison, Journal of Appalachian Studies (Fall 2003); Richard Nevell, A Time to Dance (1977); Cecil J. Sharp and Maud Karpeles, The Country Dance Book, Part V (1918); Susan Eike Spalding and Jane Harris Woodside, eds., Communities in Motion: Dance, Community, and Tradition in America’s Southeast and Beyond (1995).

Stepping

African American step teams throughout the South dazzle audiences with their dynamic, synchronized stomping and clapping and their choreographed dancing to hip-hop tunes. A complex performance involving synchronized percussive movement, singing, speaking, chanting, and drama, stepping developed in the early part of the 20th century as a ritual of group identity among African American college fraternities and sororities. Stepping reflects the African and African American heritage of those who pioneered its development, as well as the verbal and movement traditions prominent among blacks in the South.

Every year in late November, at the Bayou Classic in the Louisiana Super-dome, Grambling State University and Southern University compete in one of the largest historically black college football competitions in the United States. There, also, the best college step teams compete in the Bayou Classic Greek Show. Other competitive step shows take place throughout the South, as collegiate step teams vie for bragging rights while raising money for social causes. While such shows are the most public venue for collegiate stepping, most fraternity and sorority stepping happens on campus, where members of the nine historically black Greek-letter societies that compose the National Pan-Hellenic Council celebrate their organizations through probate (or neophyte) step shows that present new members to the public. They also sponsor competitive step shows to support scholarships and other social causes.

Stepping is a dynamic and vital performance for expressing and celebrating African American and other group identities. Popularized in films such as such as Stomp the Yard (2007), Drumline (2002), and School Daze (1988), and in TV programs such as A Different World (1987–93), stepping is now also performed by multicultural, Asian, Latino, and occasionally white fraternities and sororities, as well as by community, school, and church step teams. As other ethnic groups form step teams, they incorporate their own ethnic dance traditions into their stepping, while retaining signature African American features.

Stepping routines are orally composed and transmitted. When the step-master or leader is older than the steppers being taught, he or she may teach the routine by “breaking it down” into smaller rhythmic units that are imitated until everyone masters them. Composition is often collaborative in groups in which everyone is the same age. Circulating videotapes and DVDS of step shows (often available for sale online) aid in the transmission process; so also do video clips that are readily available on YouTube and other Web sites. Regional and national competitions, as well as regional and national meetings of the nine historically black Greek-letter societies, further help to disseminate steps. A striking example of oral composition can be seen in the way steppers use the words and tune of Omega Psi Phi’s song, “All of my love, my peace and happiness, I’m gonna give it to Omega,” as an oral formula, borrowing and modifying it as they incorporate it into various step routines. While preserving the same tune, a high school step team substituted the words “I’m going to give it to my people,” and a church step team sang, “It’s all our love and praise and honor, we want to give it to our savior—Jesus Christ.”

Each of the nine black Greek-letter societies has “trade” or “signature” steps that are performed by college chapters throughout the nation and convey the character and style of the organizations. These signature steps have names, and members within the black Greek system recognize them as belonging to particular organizations by their visual and oral patterns. When a group performs the signature steps of another organization, it does so either to pay tribute to the originating group (called “saluting”) or to mock it by performing the step in an inept or comic manner (called “cracking” or “cutting”). Some well-known signature steps include Alpha Phi Alpha’s “The Grand-Daddy” and “Ice, Ice”; Alpha Kappa Alpha’s “It’s a Serious Matter”; Zeta Phi Beta’s “Sweat” and “Precise”; Phi Beta Sigma’s “Wood”; and Iota Phi Theta’s “Centaur Walk.”

Stepping may have grown out of the popular drill team traditions of African American mutual aid and Masonic societies; it certainly reflects the same kind of emphasis on synchronized clapping and stomping. Interestingly, the founders of the first black college fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, were closely associated with black Masonic societies and held their first initiation in 1906 at a Masonic Hall, where they borrowed Masonic costumes for their ritual. The earliest written reference to what may be stepping appears in 1925, when an article on “Hell Week” in the Howard University newspaper describes Alpha Phi Alpha and Omega Psi Phi pledges “marching as if to the Fairy Pipes of Pan.”

Stepping may have also grown out of the black Greek ritual of “marching on line,” in which pledges expressed their brotherhood or sisterhood by walking in a line across campus, displaying their group’s colors and symbols. Over the years, groups added singing, chanting, and synchronized clapping and stomping to their marching. Early step shows often had the brothers and sisters moving in counterclockwise circles; as stage performances for audiences became more common in the 1960s, however, line formations became prevalent. Terms for stepping vary among campuses and change over time, and they include such designations as “demonstrating,” “marching,” “bopping,” “hopping,” “blocking,” and “stomping.”

Stepping reveals its continuity with African American dances that originated in the South during slavery. The most well-known dance of this period, “patting juba,” may have originated in an African dance called guiouba; it grew in popularity after slaveholders outlawed drums among the enslaved, for fear that they would use them to communicate and plan slave revolts. Without drums, slaves used their hands and feet to create the rhythm for their dances. Recalling this practice among enslaved dancers in Louisiana, Solomon Northup described “patting juba” as “striking the hands on the knees, then striking the hands together, then striking the right shoulder with one hand, the left with the other—all the while keeping time with the feet, and singing.” Along with this percussive movement, dancers would sing and chant, often voicing a critique of slavery in coded language. When performing in a group setting, dancers would usually step juba in a counterclockwise circle, with both the words and the steps in a conversational, call-and-response form; the dancing relied on improvisation, low-step shuffling, and clapping, all of which are time-honored features of African American dance performance.

African American dancers on the minstrel stage also performed the juba dance. The most famous such dancer of the 19th century, William Henry Lane, was called “Master Juba” because of his extraordinary step dancing. In the 1840s, Lane held dance duels in the Five Points district of Lower Manhattan with Irish step dancers, including the white minstrel dancer Jack Diamond; in these duels, he freely blended African dance elements with Irish jigs. The frequency of such blending may well account for the widespread white adoption of the term “jigs” to describe African American step dancing, according to dance historians Marshall and Jean Stearns. Thus, stepping may reflect Irish as well as African influences.

Just as the early circular routines of fraternity and sorority steppers suggest the influence of patting juba, so too may they reflect another early African American dance form, the “ring shout.” Developed in black Christian churches during slavery, ring shouts feature counterclockwise movement, hand clapping, foot patting, stick beating (to foreground the rhythm), and call-and-response singing. Though ring shouts were primarily acts of worship, they also took place in some 19th-century secular contexts, such as house parties and gatherings of black soldiers in the Civil War. Ring shouts still occur among some church communities in the South and along Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Stepping also embodies aesthetic features common in Western and Central African dances. The counterclockwise circular movement of early step routines recalls not only patting juba and ring shouts but also a common dance pattern in Kongo culture that symbolizes the sun circling the Earth, according to art historian Robert Farris Thompson. One of the most striking stances of African American stepping—the “get-down” position, in which steppers bend deeply from the waist, or step with knees deeply bent—is common in Africa. Other characteristic features of African dance, according to Thompson, include call and response, dances that convey derision, the use of striking moralistic poses, an emphasis on correct entrance and exit, personal and representational balance, the establishment of clear boundaries around dances, looking smart, the mask of the cool, and polyrhythm (multiple meter). African American steppers exhibit all of these features, demonstrating the strong continuity of stepping with African culture. Indeed, steppers often claim that stepping originated in Africa. One AKA sister, for instance, said that stepping “goes all the way back to African culture,” when different tribes competed through dance, and a Christian step team in Detroit, Mich., chanted, “Africa is where stepping began, from the beat of the drums to the sound of our feet.”

Since the early 1990s, stepping has grown in popularity and spread beyond college campuses and African American fraternities and sororities to new practitioners, audiences, and venues. Latino, Asian, multicultural, and occasionally white fraternities and sororities around the country now step, as do many school, community, and church groups. Alpha Phi Alpha brothers from Howard University stepped for President Bill Clinton’s inaugural festivities in 1993, and the opening pageant of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Ga., featured stepping. African American fraternity and sorority members have played key roles in spreading stepping to new groups and contexts by teaching others to step, starting school, church, and community step teams to mentor youth, and participating in arts organizations such as Washington, D.C.’s Step Afrika, which uses stepping as a tool to promote education and intercultural dialogue.

At the University of Texas at Austin, the Epsilon Iota Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha sponsors two different stepping shows for non-Greeks. The Non-Greek Step show in the fall is the largest in Texas and includes high school and community step teams from across the state. In the spring, it sponsors “Step for Hope,” in which the fraternity members teach students of different cultural backgrounds how to step and then perform on the main mall in front of a large audience. Participating in this step show led sisters of Sigma Phi Omega, an Asian-interest sorority, to start stepping in 1998. Another Asian-interest fraternity at the University of Texas, Omega Phi Gamma, has sponsored a Unity talent show since 1995, in which the brothers perform their special step routine. The first intercollegiate Latino Greek step show on the East Coast, and perhaps in the nation, took place in the Bronx in July 1999. By 2006, Latino step shows were common on college campuses throughout the nation and the South.

Thus, increasingly throughout the South, one can find step shows flourishing in many contexts and among social groups quite different from the historically black fraternities and sororities that invented stepping. Despite the addition of salsa movements by Latino steppers, raas and garba dance movements by South Asian steppers, or Christian chants by church steppers, the stepping of these new groups retains many characteristic African American features. Stepping has proved to be a highly malleable tradition, able to incorporate new performers and styles as it functions to demonstrate group identity through its complex, synchronized percussive movements.

ELIZABETH C. FINE

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Carol D. Branch, in African American Fraternities and Sororities: The Legacy and the Vision, ed. Tamara L. Brown, Gregory S. Parks, and Clarenda M. Phillips (2005); Elizabeth C. Fine, Soulstepping: African American Step Shows (2003, 2007); Walter M. Kimbrough, Black Greek 101: The Culture, Customs, and Challenges of Historically Black Fraternities and Sororities (2004); Jacqui Malone, Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance (1996); Marshall Stearns and Jean Stearns, Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (1968); Robert Farris Thompson, African Art in Motion: Icon and Act (1979).

Stock Car Racing

Stock car racing is a form of racing with automobiles that resemble standard production passenger cars. Stock car racing has become especially popular in the South where in its most developed forms it takes place in specialized amphitheaters using expensive, powerful, and carefully made machinery.

Automobiles were initially more plentiful in the industrialized parts of the nation, so much early automobile racing was done in the North and Midwest. Informal races were soon moved from the streets onto existing horse racing “tracks,” which were surfaced with dirt. Starting around the turn of the century, the brick-surfaced oval track at Indianapolis, Ind., served as a new focus for racing activity.

It took longer for the automobile to reach rural areas, and not until the 1930s did stock car racing as it is known today become popular in the rural Midwest and South. Mass-produced automobiles gave working-class rural southerners more personal mobility than had been provided by horses. Farmers used cars for speedier delivery of their crops to more distant markets. In some cases, they distilled crops into liquor and transported the liquor to market as part of a longstanding family business. Liquor was a compact means of transporting crops and provided a greater return. This trade was opposed by governmental authorities, because most home-liquor makers (“moonshiners”) did not pay taxes on their sales. In their efforts to outdistance law officers, some of the liquor runners skillfully modified their cars for greater power and higher speeds. The drivers of these vehicles also participated in informal races between themselves and others interested in automobiles. Liquor runners, although a small minority of those who entered early races, included many of the most famous and proficient drivers and race organizers. Some of them became legends.

With the greater affluence and hence more widespread automobile ownership that followed World War II, racing became more popular than before, especially in the South. However, the rules under which the racing was conducted and the administration of the tracks were often uncertain. A concerted effort to standardize the rules and the administration of racing resulted in the formation in 1947 of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, Inc. (NASCAR). NASCAR has become the largest and best known of such sanctioning organizations in the United States, with wide media coverage of its activities.

Virtually ignored by the national media, the first major paved amphitheater (“superspeedway”) built in the South especially for auto racing opened in 1950 in Darlington, S.C. As a result of its success, tracks opened in other parts of the South. At present, stock car races are held from New England to California, although most of the big speedways are in the South. The Carolina Piedmont has the largest concentration of tracks, major races, driver home bases, and driver folk heroes. The heartland goes from central Virginia down to Talladega, Ala.

During the 1950s and 1960s, automakers noticed that successes of a make of car in the races led to increased sales. The auto companies and other sponsors poured money into the sport as a form of advertising. Support for racing has also come from other large corporations. For instance, a cigarette company sponsors several major race series. Individual racers and racing machines also are sponsored by small businesses and individuals.

Throughout its history, stock car racing has been identified with rural white southern males. Blacks and women, although occasional participants, have never made it to the top. Racing has become an accepted way (along with others, including singing and athletics) for a rural white male to achieve fame, money, and the trappings of success. Successful participants in the sport, such as Richard Petty, Junior Johnson, and Cale Yarborough, keep aspects of their southern heritage while they develop an ability to work with big business. Many of the best racers have, along with driving skill and a mechanical genius, a razor-sharp business acumen. They base their racing activities in their hometowns and maintain close family ties. Their “pit crews” tend to be drawn from the local population. They build closeness to their fans through personal appearances and project a “good old boy” image by expressing an interest in such male activities as hunting, fishing, and, of course, tinkering with automobiles. They are folk heroes with which the average southern male can identify. Stock car racing, with its noise, dirt, powerful cars, and consumption of alcoholic beverages, has become a symbol of the southern way of living.

Stock car racing combines a fascination with technology and a spirit of competition. It has become identified with the South, where it has served both as a sport and as a way for participants to leave rural poverty. At first glance, the cars appear to be like those available to the average person. However, the cars are in fact highly specialized technical accomplishments. The cost of the machinery keeps it from being a widely popular participant sport. As a result, there is mass popular support for a relatively small number of athletes. The drivers epitomize the successful southern male who has managed to retain his “down-home” manner. The average southern male can identify with the racers, both because he drives a car that looks like theirs and because he shares their identification with things southern. At present, many of the prominent drivers are in their 40s, an age by which athletes in many other sports have retired. A few younger drivers are beginning to gain recognition in Winston Cup racing, often through their successes in local competition. Winston Cup racing is the most publicized form of stock car racing.

There are different kinds of racing, varying with the scale of the effort and the technical details of the cars. Categories often are based on the age of the cars and their construction, especially their power plants and wheelbase lengths. Rules also vary with the track where the races are run.

There is a continuum of size and complexity in racing tracks. At the amateur level are small tracks (usually oval in shape and a quarter to a half mile long), which draw spectators and participants from immediately surrounding areas. In these races, older passenger cars are modified for increased safety and speed. As in other sports, there are many participants in local-level, dirt track races, which require less money and effort.

At the professional end of the scale are Winston Cup (formerly called Grand National) races on larger speedways. Contestants come from all over the nation. Media reporters jockey for position to interview the winning drivers. At this level, vehicles are usually constructed by specialty builders solely for racing and have little relation to production cars beyond outward appearance.

At all levels of racing, each vehicle has one or more mechanics who build and maintain the vehicle. The “pit crew” services the car during races by refueling, replacing tires, cleaning the windshield, and giving the driver refreshments.

Sponsors are individuals or businesses that provide money to support the racing effort. Their names are painted on the sides of the cars (along with each car’s number) so that the fans will be encouraged to buy their products. Some drivers have consistently used particular makes of automobiles, endorsing the manufacturer. Fans are fiercely partisan toward particular drivers. Many fans wear clothing and other items imprinted with the car number and name of their driver and belong to fan clubs boosting their favorite.

Track officials work to ensure that the race goes smoothly. There are often also officials from the organization (“sanctioning body”) that writes the racing rules. Although NASCAR is the best known of these organizations, smaller, local sanctioning bodies organize most racing events. These bodies write rules to promote safety and competition.

“Technical inspections” of cars are made to ensure that cars conform to the rules. Nevertheless, clever racers try to interpret the rules to their advantage. The emphasis on technical sophistication in the preparation of the vehicles is one of the excitements of the sport, and fans and racers alike are constantly alert to innovations that increase the cars’ speeds.

Each driver is involved with several kinds of competition simultaneously. Competition for winning the race by being the first to complete the required number of laps around the track is the most visible. Winning is a combination of driver skill and chance. Winning is also dependent on the speed and efficiency of the pit crew and the ability of the machinery to last up to 500 laps at speeds up to 200 miles an hour. Behind the scenes, drivers compete for the best sponsors and mechanics.

Before the race, drivers compete in trials designed to see which car can go fastest around the track. The faster a car runs in the trials, the closer it is placed to the front of the pack of 30 to 40 starting cars. The fastest car gets the most advantageous position (the “pole” position) at the front. Drivers compete to accumulate the most “points” over a season from various accomplishments, such as the position of their car in comparison to the winner’s at the end of each race, the number of races entered, and the number of laps completed.

DAVID M. JOHNSON

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University

Patrick Bedard, Car & Driver (June 1982); Jerry Bledsoe, The World’s Number One, Flat-Out, All-Time Great, Stock Car Racing Book (1975); Pete Daniel, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (2000); Peter Golenbock, American Zoom (1993); Handbook of American Popular Culture, vol. 1, ed. M. Thomas Inge (1979); Tom Higgins and Steve Waid, Brave in Life: Junior Johnson (1999); Ed Hinton, Daytona: From the Birth of Speed to the Death of the Man in Black (2001); Mark Howell, From Moonshine to Madison Avenue: A Cultural History of NASCAR’s Winston Cup Series (1997); Jim Hunter, Official 1982 NASCAR Record Book and Press Guide (1982); Bill Libby with Richard Petty, “King Richard”: The Richard Petty Story (1977); Bob Nagy, Motor Trend (June 1981); Dan Pierce, Southern Cultures (Summer 2001), Atlanta History (no. 2, 2004); Richard Pillsbury, Journal of Geography (no. 1, 1974); Don Sherman, Car & Driver (June 1982); Southern MotoRacing (biweekly newspaper about stock car racing, Winston-Salem, N.C.); Sylvia Wilkinson, in American South: Portrait of a Culture, ed. Louis D. Rubin Jr. (1980); Tom Wolfe, Esquire (March 1965).

Storytelling

Storytelling—a means of description, entertainment, and teaching known in all cultures—has played a rich role in the South, where Native American, European, and African storytelling traditions have intermingled and enriched each other for four centuries. Despite its great age, storytelling is always new when it unfolds as part of a living tradition, because the teller shapes the tale while interacting with an audience whose tastes and values inform the performance. Without the listeners’ interest and approval, the tale dies on the teller’s lips. Because tales always emerge in the moment, we cannot know the exact styles and stories of the earliest southern storytellers; nonetheless, written records give some idea of the tales’ content and how they were performed.

Southern storytelling began with the region’s native peoples, including the Cherokee, who once inhabited the Appalachian Mountains from Alabama to West Virginia. As in all storytelling communities, the Cherokee recognized (formally or informally) certain individuals as narrative specialists. Around 1750 some of these specially trained narrators recited a long legendary history of the Cherokee, beginning with their divine creation and then tracing their migrations across North America. Nearly 150 years later, when James Mooney made the first comprehensive study of Cherokee storytelling, no one could remember this story; tribal elders did recall, however, that in the 1840s boys chosen to learn the sacred stories would sit all night around a ritual fire listening to their teachers and then would strip and bathe in a stream to purify themselves. By the end of the 19th century, the Cherokee no longer observed this ritual, though tribal elders still specialized in the most sacred stories. Of course, most Cherokees knew and told many other types of stories, including local legends, tales of notable hunts and battles, and animal tales that featured a trickster rabbit (some of which resemble the African American tales of Brer Rabbit, a fact that perhaps reflects contacts between Cherokees and African Americans stretching back to colonial times).

When Europeans first reached the South, they brought with them longstanding narrative styles with which they described both the Indians and their stories. Through their writings, Europeans introduced the New World and its people to the Old. Explorers such as the German John Lederer, who traveled through North Carolina in 1670–71, learned Indian history from traditions “delivered in long tales from father to son” that the tellers had memorized as children. Indians also taught Lederer about the natural environment—how, for example, snakes would hypnotize squirrels in trees to lure them to the ground and eat them. Although Lederer did not believe this particular tale, he nonetheless repeated it in his Discoveries (1672).

Southern explorers, following a European tradition dating to medieval times, also told stories of their personal adventures, some of which were retold through succeeding centuries. For instance, Captain John Smith—who helped establish the colony of Jamestown, Va., in 1607—often told of his capture by the Powhatan tribe and how the young Pocahontas intervened to prevent his execution. Later historians dismissed this and other Smith narratives as fiction, though recent research supports the accuracy of some of these stories. Regardless of their historicity, explorers’ stories seized the popular imagination and blended into the tradition of the tall tale—a form that became the signature genre of the American frontier.

Tall tales were so popular that they long dominated America’s periodical literature; as early as the 18th century, and throughout the 19th, almanacs and weeklies were rife with tall tales celebrating southern wilderness heroes, both famous and nameless. Tall-tale performances became features of public life: just as John Smith told explorer tales for self-promotion, political celebrities, including Tennessee congressman Davy Crockett (1786–1836) and Louisiana governors Huey P. Long (1893–1935) and Jimmy Davis (1899–2000), used tall tales to advertise themselves. A successful narrator’s tall tales sometimes even outlived him, as in the case of the Crockett almanacs, which were published for two decades after the hero’s death at the Alamo.

Usually told in the first person and always presented as true, the tall tale typically begins with a credible situation in a recognizable natural environment and then adds a series of escalating exaggerations, ending as an unbelievable fiction. A plot known to folklorists as “The Lucky Shot” neatly characterizes this genre. A man starving in the wilderness is down to his last bullet; he must kill game or die. Spying ten ducks perched on a branch, he tamps a bullet into his double-barreled, muzzle-loading rifle. But at that very moment, a bear charges him head-on, a panther leaps toward him from his left, and a boar charges from his right. With the ramrod still stuck in one barrel, he pulls both triggers at once. His one bullet kills the bear; the gun’s left hammer flies off and kills the panther; the right hammer, in turn, kills the boar. Meanwhile, the ramrod flies to the ducks, pinning their feet to the branch. The once-starving hunter collects his game; he now has food for a year.

“The Lucky Shot” captures some of the most common themes of southern tall tales: the wilderness is filled with both terrifying dangers and life-sustaining abundance; and given one last chance, a lone man—through either resourcefulness or dumb luck—secures abundance from danger’s jaws. Versions of this plot have been documented in English in performances by African American John Jackson in Virginia and Anglo Jimmy Wilson in Arkansas, as well as in French by Louisiana Cajun Adlai Gaudet and in Spanish by numerous narrators along the Gulf Coast—testimony to the fact that southern storytelling readily crosses the most rigid boundaries of culture, language, region, and race.

In contemporary southern settings, the tall tale is sometimes a large-scale affair; many county fairs and local festivals feature “liars’ contests” in which performers strive to tell the most preposterous tales. But more typical narrative communities are small, all-male groups that congregate at hunting camps, country stores, or courthouse squares. The teller usually speaks in a soft monotone of feigned sincerity, as if unaware that there is anything incredible about his story. Audience members who are “in” on the joke also betray no hint that the narrator is telling an outrageous lie. The ideal is to perform in such a low-key fashion that eavesdroppers believe they are listening in on a normal conversation. (In the Ozarks in the mid-20th century, for example, storytellers in general stores would exchange everyday news until a tourist approached. Just before the visitor reached the store, they would start telling their tall tales—about, for instance, how one of their children rode to school on the back of a friendly bear—to keep the visitor from suspecting that he was witnessing a joke at his expense.)

If the tall tale draws its power by deftly walking the line between fact and fiction, other stories—such as Märchen, or magic tale, the oral equivalent to the literary fairy tale—present an unvarnished fantasy world. The Europeans who settled the South may have carried only a few books, but they did bring a significant repertoire of Märchen. Joseph Doddridge recalled that on the West Virginia frontier, around 1770, “Dramatic narrations, chiefly concerning Jack and the Giant, furnished our young people with [a] source of amusement during their leisure hours. Many of those tales were lengthy, and embraced a considerable range of incident. Jack, always the hero of the story, after encountering many difficulties, and performing many great achievements, came off conqueror of the Giant.” Such tales as “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “Jack the Giant Killer,” beloved in 18th-century Britain, were equally popular in the southern colonies.

More than two centuries later, the hero of the southern Märchen is still typically named Jack, and the Märchen are often called Jack Tales (or Jack, Tom, and Will tales, after the three brothers featured in many versions). Like the tall-tale hero, Jack—the youngest, smallest, and least promising of the three—relies upon resourcefulness and luck to outperform his brothers and save them from menacing giants, evil witches, and fierce animals.

The performance settings for southern Märchen are generally more intimate than for tall tales. Märchen telling typically takes place at home, within the family. The specialists tend to be the oldest family members, and the listeners the youngest. Maud Long of Hot Springs, N.C., recalled how, around 1900, her mother told Märchen at night to soften the children’s labor: “after supper, all of us were gathered before the big open fire, my mother . . . sewing or carding . . . ; the older girls were helping . . . and all of us little ones would have a lap full . . . of wool out of which we must pick all the burrs . . . , and to keep our eyes open and our fingers busy and our hearts merry, my mother would tell these marvelous tales.” Märchen telling also sometimes accompanied outdoors work. North Carolinian Frank Proffitt Sr., for instance, used tales to both goad and reward his son’s labor as the two worked together in the fields. When they finished hoeing a row, the elder Proffitt would tell a tale; then when the two resumed working, the boy would hoe quickly so that he could hear another tale upon reaching the next row’s end.

By the mid-20th century, Märchen were probably best known in the bedroom, told one-on-one by elders to their children and grandchildren; such sessions were often inventively personalized. In the 1940s, for instance, Kentucky Märchen teller Sydney Farmer entertained her granddaughter Jane Muncy with nightly tales as the two shared the same bed. Though Sydney told Jack Tales, she changed the hero’s name to Merrywise to help her granddaughter identify with the hero and to subtly teach her that small, vulnerable people could triumph in life through wisdom and positive thinking. Sydney’s tales so influenced her granddaughter that Muncy—now an adult psychologist—retells them to her clients to foster the same resiliency and hope that her grandmother’s tales had given her.

African Americans in the South brought with them vast repertoires of tales from West Africa; they also learned many Märchen from Europeans. Through household situations in which black elders entertained white children, they passed on to European Americans many of their animal tales, most famously those revolving around the character Brer Rabbit. As a boy, white Georgia journalist Joel Chandler Harris (1845–1908) learned many such tales from older blacks and later published them in his Uncle Remus books (named after a fictional slave who personified the oral tradition that Harris had tapped). These books brought Harris widespread fame, though readers soon recognized that their art lay in Harris’s ear rather than in his imagination.

Long before and long after Harris wrote, rich African American narrative traditions thrived in households and at communal work and play settings. The wealth of this repertoire is exemplified in J. D. Suggs (1887–1955), a storyteller who shared 175 tales with folklorist Richard Dorson in the 1950s. Born in Kosciusko, Miss., to sharecropper parents, Suggs learned his first tales from his father at home. As he grew, he traveled widely before settling down to raise a family in Arkansas and eventually moving north to Chicago and Michigan. Throughout his adult life, he shared his family tales (and ones he learned during his travels) with friends and coworkers. Suggs’s narrative style, like that of many African American storytellers, was dramatically expressive, marked by constant variations in pitch and rhythm as he impersonated story characters, imitated animal sounds, and interjected snatches of chants and song. He specialized in many genres, including animal tales, tall tales, witch legends, magic tales, traditional historical stories, and anecdotes revolving around the competition between a wily slave named John and his white master.

Since the mid-20th century, the normally small-scale art of storytelling has acquired an increasingly public and professional face through the formation of storytelling societies and festivals. The largest venue for such performances is the National Storytelling Festival—held every October in Jonesborough, Tenn., which explicitly seeks to bring together traditional and professional narrators. At Jonesborough, in public library storytelling hours throughout the South, and on “ghost tours” (regularly conducted in New Orleans, La.; San Antonio, Tex.; Savannah, Ga.; and many other southern cities) master storytellers attract crowds of mutual strangers to experience together, in new ways, the power of one of the world’s oldest art forms.

CARL LINDAHL

University of Houston

John A. Burrison, ed., Storytellers: Folktales and Legends from the South (1989); Richard M. Dorson, ed., American Negro Folktales (1967); Carl Lindahl, ed., American Folktales from the Collections of the Library of Congress (2004); William Bernard McCarthy, Cheryl Oxford, and Joseph Daniel Sobol, eds., Jack in Two Worlds: Contemporary North American Jack Tales and Their Tellers (1994); Leonard W. Roberts, ed., South from Hell-fer-Sartin: Kentucky Mountain Folk Tales (1955); Vance Randolph, We Always Lie to Strangers: Tall Tales from the Ozarks (1951); Joseph Daniel Sobol, The Storyteller’s Journey: An American Revival (1999).

Tennis

Lawn tennis in the South shares much of the same general history as golf. Lawn tennis originated in the United States in New York in the 1870s and soon spread through the Northeast, Middle West, and the Pacific Coast. The United States Tennis Association (USTA), founded in 1881, soon governed the sport of tennis. A few southern cities such as New Orleans promoted the sport, but it was not a popular one until well into the 20th century. It lost many of its aristocratic trappings in the 1920s and became a middle-class game. Tennis celebrities such as Big Bill Tilden and Suzanne Lenglen became popular in the South as well as elsewhere. In the South the game was a country club sport, but the 1930s saw an increase in the building of public courts, as with the building of community golf courses.

Tennis did not lose its country club image until the 1950s and 1960s. The game became more popular in those years with the emergence of appealing young stars, television coverage of major tournaments, large money payoffs to tournament winners, and the establishment of an open system of competition between amateurs and professionals. The Southern Tennis Association, based in Norcross, Ga., is the largest of 17 regional sections of the USTA, with over 180,000 members in 2009. Major tournaments are now held in the South. In 1970 Texas millionaire Lamar Hunt financed World Championship Tennis, which sent professional players on tours around the world. Tennis can now be found as an activity at southern resorts, and it can be played on public courts in cities and small towns throughout the region. The South, however, has produced surprisingly few of the game’s great players. Chris Evert from Florida is one of those, winning 157 professional singles titles on a 1,309–146 won-lost record in her career from 1969 to 1989. Tennis has not drawn the attention of many southern writers, but Rita Mae Brown’s Sudden Death (1983) and Barry Hannah’s Tennis Handsome (1985) have tennis players as the central characters.

The black community supported a vibrant tennis culture in the days of Jim Crow social segregation, with the South at the center of a network of institutions and coaches that produced some of the game’s historic figures. The American Tennis Association is the oldest African American sports organization, founded in 1916 and holding its first national championships at Baltimore’s Druid Hills Park in August 1917. The organization now consists of member country clubs throughout the nation and the Caribbean, and it provided until recently the only courts where blacks could play tennis and compete for championships. Coaches, both professional and amateur, worked to develop talent. Walter Johnson, a physician in Lynchburg, Va., opened his home and backyard court to young black players every summer, helping to produce two of tennis’s greatest players, Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe. Gibson, at age 23, was allowed to play in the 1950 U.S. championship, the first African American to do so, and she won the singles championship there in 1957. She would win five of the prestigious Grand Slam championships, including twice at Wimbledon. Ashe had an equally successful career, winning both the U.S. Amateur and the U.S. Open championships in 1968. In an 11-year professional career cut short by an early death, Ashe won 33 singles titles, including defeating Jimmy Connors to win the singles championship at Wimbledon in 1975.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

E. Digby Balzell, Sporting Gentlemen: Men’s Tennis from the Age of Honor to the Cult of the Superstar (1995); Will Grimsley, Tennis: Its History, People, and Events (1971); Cecil Harris and Larryette Lyle-Debose, Charging the Net: A History of Blacks in Tennis from Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe to the Williams Sisters (2007).

Tourism

Tourist. The word evokes images of Hawaiian shirts and Bermuda shorts, Instamatic cameras and sun-reddened skin, a clay-streaked station wagon, laden with luggage and sacks of Florida oranges. Those millions of wayfarers who hurdle along interstates to bake on sunny beaches and see Rock City pump billions into the southern economy each year.

Tourism has become as much a part of life for Americans as work in the week and church on Sunday. The modern burst of tourism began in the late 1940s. Veterans, who could not be kept down on the farm after they had seen the world during the war, earned their two weeks of vacation and hit the highways for recreation, relaxation, and entertainment. Nearly every family now marks days off its calendar for a vacation, even two or three a year. Despite oil shortages and the recessions of the 1970s and early 1980s, Americans winced at gasoline prices, dipped into savings, and pointed their cars and campers South.

A century and more before, the purpose of most travels in the South was for health. By the late 1700s travelers eased into hot springs baths to unlimber muscles. Modern-day resorts such as the Greenbrier in West Virginia and the Homestead in Virginia trace their origins to those times and still offer bathing facilities.

For more than a century, Carolinians who lived along the coast traveled to save their lives. Spring through fall, or “frost to frost,” they fled the malarial, soggy low country for the spice of mountain air. Hendersonville, N.C., is still called “Little Charleston in the Mountains,” and many of the summer cottages, dating back to the mid-1800s and handed down through the generations, still stand.

In the decades after the Civil War, northerners invaded the South again, but this time as tourists in a campaign for their health. The mineral waters of southern springs and the salubrious southern climate were touted for their curative benefits. Physicians prescribed winter vacations in towns like Thomas-ville, Ga., which once boasted 15 hotels, 25 boardinghouses, and 50 winter cottages.

From the late 19th century to the mid-20th, pleasure travel evolved from a privilege of a wealthy few to an affordable luxury for the average family. A growing economy was partly the reason, but so also was the increasing ease of transportation—from carriages on dirt roads to railroads to family cars on interstates.

Of all southern states, Florida best symbolizes the rise of tourism. To see Florida in the mid-1800s, when much of the state was still wilderness, travelers had to go by boat. Honeymooners took romantic excursions along the Suwannee River, the St. John’s, and the Oklawaha to Silver Springs. Often the land alongside was scented with orange blossoms in spring, and, at night, the light from burning pine knots played on the overhang of cypress and Spanish moss. By the 1890s railroads were skimming the shoreline of both coasts; Henry Flagler linked Jacksonville to the squat settlement of Miami, building alongside his railroad such palatial hotels as the Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine and the Breakers in Palm Beach.

Down Flagler’s railroad came the very rich. But along the increasing miles of paved highways came the families of average means that, in the flush times of the 1920s, could afford pleasure travel. They fashioned homemade campers on Model-T’s, ate store-bought food from tin cans, and camped beside the roads. These “tin-can tourists,” as Floridians called them, pioneered the major mode of travel of two decades later—the family car. In the exuberance of release from the Depression, and with a car in every garage, Americans joyously flooded the highways of the South.

With war boom babies in the back seat, they traveled to the beach in summer and the mountains in the fall. Quiet seaside villages like Myrtle Beach, S.C., and mountain towns like Gatlinburg, Tenn., grew into garish neon playgrounds. The family spent nights in tourist courts, stopped at roadside souvenir stands, visited alligator farms, toured Mammoth Cave, walked Civil War battlefields, and yes, saw Rock City. Later, such “attractions” as theme parks offered rides and Broadway-type entertainment in a milk-and-cookies family atmosphere.

Quickly, tourism became an industry with a manufacturing mentality to mass-produce. Kemmons Wilson of Memphis, founder of Holiday Inns, and other entrepreneurs stamped one motel after another from the same mold. Fast food franchises arched their signs above highways. Many of those motels and packaged food restaurants rise at exits of interstates that tie doorsteps to destinations, bypass towns, and hold the countryside at arm’s length. Now, in driving 800 interstate miles, travelers may sleep in the same room every night, eat the same hamburger for every meal, and never see a town.

Why and to where do tourists today go on vacation? One large segment of the population indicates that three main factors, excluding cost, determine vacation destinations. Readers of Southern Living magazine, certainly the epitome of the middle-class southerner, say they travel primarily for scenery. And to most, scenery means mountains and seashore. Second, they go where they will find good restaurants and lodging: to resort condominiums on barrier islands and to quiet country inns in the mountains. And third, they choose routes and destinations to see historical sites. Even on pleasure trips to fish, swim, play golf and tennis, shop, hike, and canoe, southerners will stop a time or two to pay homage to the past.

Tourists who walk the narrow streets of Charleston pour some $460 million annually into the local economy. About 1 million visitors each year walk the battlefield at Vicksburg, Miss., and stroll through the re-created city of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. Through travel, southerners continue to learn of life of a century or two ago. In the 1930s garden club ladies in Natchez introduced a new genre of travel when it opened a few antebellum homes each spring to visitors. The name of such tours—pilgrimage—is appropriate for southerners’ reverence of the past.

Many historic homes are open for lodging as well as tours, so guests may dream they dwelt in marble halls. At preserved villages like Old Salem in Winston-Salem, N.C., visitors watch costumed docents work at the crafts and cookery of two centuries ago. The Mississippi Museum of Agriculture and Forestry in Jackson moved an entire 100-year-old farm to its premises, where southerners hear words that have almost vanished from the daily vocabulary: singletree, laying-by time, bust the middles. Workers at the farm even plant a tiny patch of cotton and let the visitor try his or her hand at picking.

Historically, tourism for African Americans was a complex process. Uncomfortable and unhealthy Jim Crow railroad cars hardly encouraged travel over long distances. Automobiles gave more privacy and security, but difficulties in finding places to eat and sleep complicated touring. Blacks nonetheless developed particular travel locations, such as black-only beaches. With desegregation of the South’s public facilities in the 1960s and a growing commercialization of black history, tourism among blacks visiting southern tourist destinations increased. Alabama’s Black Heritage (1983) was a pioneering effort to promote African American heritage in the South, and other states and cities have targeted black tourists to heritage tourism sites.

GARY D. FORD

Southern Living

W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (2006); Ruth Camblos and Virginia Winger, Shopping Round the Mountains (1973); Charleston Trident Chamber of Commerce, Tourism Profile, 1982–83; John A. Jakle, The Tourist: Travel in Twentieth-Century North America (1985); Jeffrey Limerick, Nancy Ferguson, and Richard Oliver, America’s Grand Resort Hotels (1979); Edward A. Mueller, Steamboating on the St. John’s, 1830–1885 (1980); Anthony J. Stanonis, ed., Dixie Emporium: Tourism, Foodways, and Consumer Culture in the American South (2008); Richard Starnes, ed., Southern Journeys: Tourism, History, and Culture in the Modern South (2003); Southern Living (December 1983, April 1984); Travel Survey of Southern Living Subscribers (1984).

Tourism, Automobile

The automobile represents many ideals of American culture such as individual freedom, technological dominance, and the pursuit of happiness, and the American South has long been a popular destination for many on the road and on the move. The temperate climate of the region, in addition to the lure of sandy white beaches and the beauty of the Appalachian Mountains, made automobile tourism in the South a popular recreational activity. Tourism is one of the top three economic forces in every state that constituted the Confederate States of America from 1861 to 1865. During the modern era, the South has experienced many changes brought about by the increased mobility and cultural exchange facilitated by automobile tourism. The influx of travelers and retirees to the region has caused a demographic and cultural shift.

Before the 20th century, the wealthy were the only ones able to engage in recreational travel. Many northern industrialists enjoyed the mild climate and healing waters—both oceans and hot springs—of the South. Many visited the region to vacation, build homes, and, perhaps late in life, migrate south for retirement. Northern capitalists J. P. Morgan, William Rockefeller, and Marshal Field all built elaborate homes and a country club on the once exclusive Jekyll Island in Georgia. The bucolic landscape and temperate climate of the South made the region especially alluring. Southern land was also inexpensive and largely undeveloped in the 19th century. As time went on, vacationing became a more accessible and common activity for all Americans.

When Henry Ford began to mass-produce the Model T in 1908, the first affordable automobiles began to open tourism to the average American. Yet the South left much to be desired in developed roads and infrastructure. The accessibility of the automobile combined with the Good Roads Movement to further democratize southern tourism. With the construction of the National Highway, connecting New York City to Atlanta, in 1909 and the Capital Highway, stretching from D.C. to Atlanta, in 1910 the North-South tourist trade was burgeoning. A few years later, in 1914, Carl Fisher was instrumental in developing the Dixie Highway, which connected Michigan to Fischer’s developing resorts in Miami Beach, Fla. The Dixie Highway was developed with an eastern and a western route to maximize the tourist sites and towns along the way.

The trajectory of roads could make or break small communities that depended on tourist dollars. Following the development of the 1926 National Highway System, many new roads led to roadside attractions such as auto-camps, filling stations, and a plethora of roadside stands selling various wares. Southern attractions have long played up the region’s rich history, especially the Revolution and the Civil War. The biggest monument to the Confederacy began in 1915 when the United Daughters of the Confederacy started planning a bas-relief carving of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and “Stonewall” Jackson on Stone Mountain in Georgia. The mountain is also infamous for being the site of the revival of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915. In the 1920s, Gutzon Borglum began the carving only to leave after disagreements with managers. The next artist destroyed Borglum’s beginnings, and the project was not completed until the early 1970s. Today, Stone Mountain State Park draws many tourists. Stone Mountain is a tourist attraction that possesses both a complicated history and the allure of natural beauty and recreation.

One of the major reasons to pack the kids in the car was to see the country and experience different places. With all of the families on the road with more money and increased leisure time in the postwar era, there was a need for various roadside attractions. One of the most recognizable sites along the southern roadways is the yellow and red sign advertising Stuckey’s pecan shop and roadside stand. Williamson Sylvester Stuckey went into the pecan business just as the southern roadside trade was booming. Stuckey is representative of many people who went into one business and ended up diversifying to take advantage of all those cars on the road needing gas and the tourists craving food and cheap souvenirs.

In addition to natural attractions such as beaches and mountains, the early era of automobile tourism also added destination tourism attractions such as Kentucky’s Wigwam Village, South Carolina’s South of the Border, Florida’s Cypress Gardens, the resort of Gatlinburg, Tenn., and Arkansas’s Dogpatch USA, just to name a few. Walt Disney World, located in Orlando, Fla., opened in 1971 and today is the nation’s largest and most popular example of destination tourism. The South has always offered cultural and heritage tourism spanning from Colonial Williamsburg, to Revolutionary and Civil War battlefields, to the federal funding of a Gullah-Geechee Heritage Corridor to preserve the distinctive African American culture along the southeastern coast.

Early in the 20th century, auto camping took the form of “gypsying” and engaged the American values of independence and self-reliance. Later, as a growing consumer society evolved and the democratization of travel and leisure ensued, the roadside became a largely tame, commercialized, and homogenized landscape. There was a lull in the development of automobile tourism during the Great Depression and both world wars. Following World War II, a booming postwar economy and consumer culture led to an extensive expansion of tourism. In 1956 Eisenhower’s push to develop a transportation system and the passage of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways helped both to defend the country against foreign threats and to provide better transportation for its citizens. The development of good roads often led to sunny seaside resorts and campy roadside attractions as well as national defense. The dominance of high-speed superhighways in the 1970s served to destroy local color as well as decimate old neighborhoods and businesses. The places and people left behind were often poor and black, such as in Overtown, an African American community in Miami that was displaced by the building of Interstate 395. The interstate led to a more homogenized roadside culture with chain motels, gas stations, and restaurants. However, the South had developed a reputation for its distinctive regional flair and southern hospitality even in the face of a mundane commercial roadside.

Southerners are known for the emphasis they place on hospitality and recreation. The mythologized “southern hospitality” of the region’s inhabitants is complicated by its hostility toward outsiders and history of racism. The influx of automobile tourism, which drew snowbirds and a more geographically diverse citizenry, has served to change a region that has often been hostile toward change. Tourism can lead to a more complex and open South; however, it also can lead to overdevelopment of the region’s natural resources and the dominance of developers and large corporations that care little for regional flavor and local color. Tourism has often been seen as a double-edged sword because of the complexity of the positive and negative repercussions. Appealing to outsiders has often led to the proliferation of misconceptions and stereotypes about the South, such as the ignorant Hillbilly or the myth of the Lost Cause and idyllic antebellum South.

From the autocamps of the 1930s to the chain hotels of today, the South has sold itself as a land of southern hospitality, old-time charm, and beautiful landscapes. Local images and historical memory have often conformed to the expectations of tourists. The hospitality industry in the South was primarily segregated until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 desegregated public accommodations. Southern leisure culture still struggles with its legacy of segregation and racism. The automobile leveled class differences in America, and it also potentially offered more freedom to African Americans to travel undisturbed by Jim Crow segregation. However, automobile travel could be a dangerous gamble for African Americans traveling through the South. From the 1930s until the end of the 1950s travel guidebooks, such as The Negro Motorist Greenbook and Travelguide, provided African Americans with suggestions for “vacation and recreation without humiliation.” However, “driving while black” could be a major problem in the South. For example, in 1948 Robert Mallard was attacked and killed by a Georgia mob for simply being a prosperous black man with a nice car. In the face of southern racism, guidebooks and word of mouth led to the development of strong black communities and businesses based in recreation. Beaches for African Americans, such as Florida’s American Beach and South Carolina’s Atlantic Beach, survive today. Many key moments in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s centered on the mobility of African Americans, such as Rosa Parks’s protest against sitting in the back of a bus and the “Freedom Rides” that civil rights organizations undertook during the period. Southern automobile tourism serves as one battlefield for the meaning of modern citizenship, mobility, and freedom.

Automobile travel in the South deals with the serious nature of race relations and the frivolous aspects of campy roadside attractions. The act of driving to or through the South has certainly changed in the 21st century. While regions of the United States are much more connected today, there are still signs of a distinctive southern culture to be found while touring the American South.

NICOLE KING

University of Maryland at Baltimore County

Warren James Belasco, Americans on the Road: From Autocamp to Motel, 1910–1945 (1979); Tim Hollis, Dixie before Disney: 100 Years of Roadside Fun (1999); David L. Lewis and Laurence Goldstein, eds., The Automobile and American Culture (1980); C. Brenden Martin, Tourism in the Mountain South: A Double-Edged Sword (2007); Cotton Seiler, American Quarterly (December 2006); Claudette Stager and Martha Carver, eds., Looking beyond the Highway: Dixie Roads and Culture (2006); Richard Starnes, ed., Southern Journeys: Tourism, History, and Culture in the Modern South (2003).

Tourism, Culinary

In 1936 Kentuckian Duncan Hines published the country’s first restaurant guide, Adventures in Good Eating. In the introduction to the book, Hines explained that his “interest in wayside inns is not the expression of a gourmand’s greedy appetite for fine foods but the result of a recreational impulse to do something ‘different.’” With that declaration, one could argue, culinary tourism was born.

Culinary tourism is the search for vernacular eating and drinking experiences that are specific to place. Folklorist Lucy Long describes culinary tourism as the “intentional, exploratory participation in the foodways of an other—participation including the consumption, preparation, and presentation of a food item, cuisine, meal system, or eating style not one’s own.” Culturally, the concept has its roots in the development of automobile travel and the expansion of personal eating experiences outside the home. Once the Model-T began bouncing down the dirt roads of the South, drive-ins and roadside cafés sprang up to greet them, showcasing local and regional foods and growing in popularity as travelers were exposed to new recipes and ingredients.