Drive-in Theaters

The drive-in movie theater—synonymous with the Fabulous Fifties, poodle skirts, rock and roll, and the golden age of American car culture—was the creation of a New Jersey inventor and automotive soap salesman named Richard Hollingshead Jr. In 1933 Hollingshead opened the first drive-in theater in Camden, N.J. Three years later he sold the business and turned his attention to collecting royalties from the patent. This proved useless, as a patent court ruled that Hollingshead’s invention—essentially an amphitheater for cars—was unpatentable. The result was a financial setback for Hollingshead, but it ultimately led to the widespread appearance of drive-ins across the United States, particularly in the South, where they proliferated in greater numbers than in any other region of the country.

The earliest drive-in to be built in the South was the Drive-in Short Reel Theater in Galveston, Tex. It opened in July 1934 and operated for less than one month before it was destroyed in a storm. (It was not rebuilt.) Florida saw its first drive-in open in 1938, and other southern states followed soon after. Nevertheless, drive-ins were not as popular with the movie-going public when they first appeared as they would be later on. It would be almost two decades before every state in the nation had one, let alone every sizable town.

The earliest drive-ins were generally regarded as novelties, met with amusement but low expectations. Outdoor theaters were nothing new, certainly not in the South. In the days before air-conditioning, when many indoor theaters closed down during the stifling summer months, film exhibitors experimented with temporary outdoor screens in parks, on beaches, and even in the middle of towns. The addition of automobiles to the seating arrangement was certainly novel, but it did not necessarily improve the experience. Technical difficulties (particularly with sound equipment) plagued drive-ins from the start, and economic conditions in the 1930s made their initial prospects for success unfavorable. This situation, combined with a nationwide moratorium on new theater construction during World War II, meant that drive-ins had to wait until after the war was over to attract significant audiences and investors.

The prosperous postwar era created the perfect set of circumstances that allowed the drive-in to flourish. Employment was up, the rush to the suburbs was on, and American families had disposable income to spend. The statistics on drive-in theater construction are revealing. As of 1946, there were just over 100 drive-ins scattered throughout the United States. Two years later, census data shows that figure leaping to 820; six years after that, 3,775. The upward trend was especially noticeable in the South. In Georgia, the number of drive-ins climbed from 13 in 1948 to 128 in 1954. In the same six-year period, Florida saw a rise from 22 to 158 drive-ins; North Carolina, from 66 to 209; and Texas, from 88 to 388, surpassing every other state. By 1958 an all-time high of 4,063 drive-ins across the country accounted for more than 20 percent of all ticket sales in the American motion picture industry.

The drive-in theater embodied something of the spirit of America in the 1950s—it represented expansion, indulgence, consumption, and an intense love of the automobile. In the comfort of their success, drive-in owners began to exhibit a kind of gaudy showmanship, not only in their flashy neon marquees but in their creative appeals to local or regional identity. The Cedar Valley Drive-In in Rome, Ga., disguised itself as a southern plantation, with the screen tower concealed behind a neoclassical facade, complete with Greek columns. Other drive-ins adopted names and marketing schemes designed around hometown sports teams, industries, and allegiances. There were the Razorback in Little Rock, Ark.; the Varsity in Tuscaloosa, Ala.; the Bourbon in Paris, Ky.; the Battlefield in Vicksburg, Miss.; as well as numerous Rebels, Magnolias, Azaleas, and Dixies.

Of course, not all southern audiences experienced a night at the drive-in equally. Just as most indoor movie houses were segregated, many southern drive-ins had separate entrances, restrooms, concession facilities, and parking areas for African Americans. Some drive-ins, such as the Lariat in Fort Worth, Tex., catered to blacks only, while others excluded them altogether.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, attendance at drive-ins began to trail off, as television rapidly changed the way Americans thought of an evening’s entertainment. The quality of the moviegoing experience also worsened, as drive-ins were often stuck screening low-rent films on their second or third run, while indoor theaters (many owned and operated by Hollywood production companies) showed newer and better fare.

In a last-ditch effort to stay open, many drive-ins resorted to screening pornographic “skin flicks,” a practice that actually did more to hurt their chances of survival. In 1969 Alabama governor Albert Brewer made national headlines by ordering state troopers to shut down six different drive-ins for violating the state’s antiobscenity law. Other states around the country pursued a similar course, forcing scores of drive-ins out of business.

By the 1970s, indoor film houses were adding screens and turning into multiplexes capable of housing six, seven, and eight screens in a building and running films throughout the day and night. Drive-ins, open only at night, could hardly compete. Moreover, as cities expanded toward the suburbs and land values rose, many drive-in owners sold out. All of these factors and more signaled the beginning of the end for the drive-in. By the 1990s, the number of drive-ins in the United States had dwindled to a few hundred.

Recently, however, the decline has actually started to reverse, if only gradually in a few pockets around the country. The trend is most noticeable in sparsely populated rural areas in the South, where land is cheap and the nearest multiplex is a considerable distance down the road. With few exceptions, these new drive-ins are more toned-down affairs than their predecessors. Gone are the colonial mansions, elaborate marquees, and ostentatious displays of yesterday. Construction tends to be simple and functional, while sound and projection technology has vastly improved. Film quality has also improved, as distributors hustle to get new releases on every available screen before the DVD release. As a result, drive-ins no longer have to run second-rate fare. Now they screen the same blockbusters playing at multiplexes with stadium seating. Although they will probably never reach their former numbers again, drive-ins have found a niche in the modern South by adapting to suit modern tastes.

AARON WELBORN

Washington University in St. Louis

Elizabeth McKeon and Linda Everett, Cinema under the Stars: America’s Love Affair with the Drive-in Movie Theater (1998); Don Sanders and Susan Sanders, The American Drive-in Movie Theatre (1997); Kerry Segrave, Drive-in Theaters: A History from Their Inception in 1933 (1992).

Earnhardt, Dale

(1951–2001) NASCAR DRIVER.

A seven-time Winston Cup champion, Dale Earnhardt was one of the most successful, popular, and unpopular drivers in NASCAR history. For many people Dale Earnhardt epitomized the rough-edged Piedmont working-class roots of the sport with his hard-charging, win-at-all costs style of driving. At the same time, however, he transcended those roots to become one of the wealthiest and most influential athletes in the history of American sport.

Earnhardt was born in the Piedmont mill town of Kannapolis, N.C. His father, Ralph Earnhardt, was a stock car racing legend on small dirt tracks and asphalt “bullrings” in the Carolinas and won the 1956 NASCAR sportsman championship. Dale served as a virtual apprentice with his father as he traveled with him learning the art and craft of both racing and stock car mechanics. He dropped out of school at 16 and went to work in a local cotton mill, was married at 17, a father at 18, and divorced at 19.

Earnhardt began his racing career in 1970 in a pink 1956 Ford Club Sedan owned by his brother-in-law. He soon became a fixture on local Piedmont tracks and quickly moved up through the ranks, occasionally securing a chance to drive underfunded cars at Winston Cup races. Racing, however, put him deeply in debt, brought him little fame outside a narrow circle, and even helped cause a second divorce.

His luck changed in 1979 when, on the verge of bankruptcy, he impressed car owner Rod Osterlund enough to secure a full-season ride in a well-financed car. He won his first race in NASCAR’S top division that year and rookie-of-the-year honors. The next year brought five wins, his first Winston Cup championship, and $671,990 in winnings. In little over a year and a half, Earnhardt had gone from being virtually destitute to standing at the top of the racing world. However, long-term success did not come easily for him. Osterlund sold the team in the middle of the 1981 season and Earnhardt was again consigned to inferior equipment.

Earnhardt’s career took off once again in 1984 when he returned to drive for one of his earlier car owners, Richard Childress. The pairing with Childress proved magical as over the next 17 years Earnhardt won 67 Winston Cup races and six championships in the number 3 Chevrolet. Along the way his stubbornness and his penchant for rough and aggressive driving—“I didn’t mean to wreck him, I just meant to rattle his cage”—earned him the nicknames of “Ironhead,” “The Intimidator,” and, after adopting a black paint scheme, “The Man in Black.” Earnhardt’s style and his success on the track made him both the most beloved driver on the NASCAR circuit—particularly to working-class fans—and the most hated, and he seemed to revel in both roles.

Earnhardt became almost as important to the sport as a pioneer in the marketing of his image. His business savvy, and that of third wife, Teresa, helped make him one of the wealthiest celebrities in the United States through souvenir sales, endorsement contracts, and solid investments. The once shy, uncouth, ninth-grade dropout even became a smooth celebrity spokesperson and helped to solidify the place of NASCAR in the national consciousness as an up-and-coming national pastime and not just a redneck sport for southern “good old boys.”

Earnhardt defied the odds late in his career and continued to be a consistent winner even in his late 40s. Indeed, his rivalry with the polar opposite, California-born Jeff Gordon gave NASCAR one of its most compelling story lines in the 1990s and helped to further boost the sport’s popularity. His career and life ended, however, on 18 February 2001 when he was killed in a last-lap wreck at the Daytona 500. While the outpouring of grief was most intense around his Piedmont North Carolina home, the cover photos and major tribute pieces in every major news and entertainment venue in the nation dramatically testified to Dale Earnhardt’s, and NASCAR’S, national popularity and influence. There was a silver lining to Earnhardt’s death in a renewed emphasis on safety in NASCAR. In the aftermath of his accident, NASCAR mandated a number of safety features—ironically, some resisted by Earnhardt during his life—that have made the sport notably less dangerous.

Dale Earnhardt’s death ended an important era of NASCAR history. He would prove to be the last of the southern Piedmont-born, high-school-dropout, tough-as-nails, working-class NASCAR heroes that had been so important to the sport’s origins and growth. At the same time, Earnhardt had helped transform the sport through his extraordinary talent and business savvy into an increasingly popular national pastime.

DANIEL S. PIERCE

University of North Carolina at Asheville

Charlotte Observer Editors, Dale Earnhardt: Rear View Mirror (2001); Kevin Mayne, 3: The Dale Earnhardt Story (2004); Leigh Montville, At the Altar of Speed: The Fast Life and Tragic Death of Dale Earnhardt (2001).

Easter

Easter is a Christian religious holiday celebrating Christ’s victory over death, an occasion that has especially resonated in the South with its large evangelical Protestant population that highlights the centrality of rebirth. Christian groups of all varieties make it a joyous day, the Sunday when more people typically attend church than any other. It is also a spring ritual that marks a seasonal turn toward earthly renewal.

Southerners enjoy the traditional symbols of Easter. The Bermuda lily (or simply, Easter lily) is widely displayed in churches, homes, and businesses. Families decorate colored Easter eggs; Easter morning finds Easter baskets filled with candy and fruit; and public parks and home yards are sites for Easter egg hunts—all highlighting the importance of children to the day. Easter bunnies are associated with the holiday, a symbol of fertility like the egg. Some families give baby chicks as a seasonal gift at Easter. Chocolate eggs, bunnies, and chicks represent only one example of commercial use of the season’s symbols. Southerners have long bought or made new clothes, “Easter finery.” Other Americans might wait until Memorial Day to wear white shoes or clothes, but southerners knew that Easter was the correct time for that display. Ham is the typical food that anchors Easter dinners, but the growing popularity of lamb is seen in food writer Damon Lee Fowler’s Savannah Easter Dinner menu that includes roast lamb with bourbon and mint. Since the 1950s, television has structured many families experience of the holiday, as they gather on Easter night to watch religious-themed films like The Ten Commandments or The Robe.

Americans in general mark Easter with parades, and southerners are no exception. The parade in St. Augustine, Fla., makes much of that city’s historic role as the oldest permanent settlement in the nation. Its Parada de los Caballos y Coches is a picturesque event that includes horse-driven Spanish carriages, decorated floats, beauty queens, military drill units, men on horseback, and women marching in antique costumes. The parade is part of the city’s Easter week festival that began in 1958.

Religious activities are central, though, to Easter. Some faiths have clergy wearing white vestments, with most having special music for the day, whether “Christ the Lord Is Ris’n Today, Alleluia!” in liturgical churches, or “Up from the Grave He Arose” in evangelical tradition. Late morning Sunday congregational services are preceded by early “sunrise services” at dawn. These services are often interdenominational and began in outdoor locales of special beauty or significance—on mountaintops or hillsides, in parks, in cemeteries, on ocean beaches or riversides, or at historical landmarks. Probably the first Easter sunrise service was held by the Moravians in 1771 at Salem, N.C. The preliminary activities began as early as 1:30 A.M. with a Moravian band awakening townspeople. The service formally began at dawn on Salem Square in front of Old Salem’s Home Moravian Church. Other older sunrise services took place at scenic Natural Bridge, Va., Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, the Stephen Foster Memorial on the Suwannee River at White Springs, Fla., and Cypress Gardens’ Lake Eloise. Today, many southern cities host nonsectarian sunrise services.

Easter Rock is an Easter vigil ritual that has been documented in rural Louisiana African American churches since before the Civil War. It ceremonially goes through Jesus’s time in the tomb and his resurrection. Participants gather at ten o’clock on Saturday night and hear singing. The culmination is a procession of people dressed in white entering the church, led by a man carrying a “banner” representing Christ symbolism. Twelve women, known as “sancts,” follow the leader, carrying kerosene lamps as they move. Devotionals and homilies are given, and a table is set up filled with cakes, punch, and lamps. The “rock” ceremony is the syncopated marching around the table, accompanied by the congregation’s call-and-response acapella singing and the sound of the steps of the rockers. One participant in the ceremony in the early 20th century said the name “Easter rocks” came from the fact that “everything rocks.”

Perhaps the most famous literary portrayal of Easter reflects the spirit of Easter Rock. William Faulkner, in The Sound and the Fury (1929), writes of the black woman Dilsey, servant of the decaying Compson family, who attends an Easter morning worship conducted by the Reverend Shegog. Dilsey takes the idiot child Benjy to the black church, despite complaints from blacks and whites about this violation of segregation. Shegog preaches of the Egyptian bondage and the children of God. He preaches of the Crucifixion of Jesus and the Resurrection. The congregation sways to the emotional rhythms of the sermon, Benjy sits “rapt in his sweet blue gaze,” and Dilsey “sat bolt upright beside, crying rigidly and quietly in the annealment and the blood of the remembered Lamb.”

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Hennig Cohen and Tristram Potter Coffin, eds., The Folklore of American Holidays (3rd ed., 1999); Jane M. Hatch, ed., The American Book of Days (3rd ed., 1978).

Everglades National Park

Dedicated in 1947, Everglades National Park was the first park within the national system founded to protect an area’s biological endowments. In the view of policy makers and wilderness advocates, the tabletop flat terrain of the Everglades lacked an awe-inspiring natural monument—a cascading waterfall, a looming mountaintop, an incredible geyser—that had been a prerequisite for other national parks. Yet the Everglades had considerable recreational possibilities, another important standard required for national park status.

The men and women who spent nearly 20 years campaigning for the establishment of an Everglades national park recognized they were trying to sell to the public a place most Americans regarded as a swamp and wasteland. Although the park proponents worked hard to convince others to see unique beauty in the region, they leaned heavily on the recreational benefits the great expanse offered. For several decades before the founding of the park, the Everglades were popular for hiking, camping, boating, fishing, and hunting (an activity later prohibited in the park) opportunities. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some of the country’s best-known ornithologists, including Harold H. Bailey, found great leisure in bird watching in the Everglades. It was by way of this activity that Marjory Stoneman Douglas, a park founder who in the late 20th century emerged as a central figure in the campaign to restore the beleaguered Everglades ecosystem, first became intimate with the Everglades. Ernest Coe, a semiretired landscape architect who in the 1920s launched the campaign to establish a national park, spent countless sublime hours hiking and camping in the Everglades. When parks in the North closed during cold months, Coe argued, the subtropic park in South Florida would serve as a prime recreational spot during the winter season.

Boosters in the state who supported the park believed Everglades would attract one million tourists a year (a number not reached until decades later). Governor Spessard Holland, who was instrumental in the final push for the park’s creation, envisioned motor tourists driving down through the long state and stopping to spend their money at filling stations, restaurants, motels, and roadside attractions before reaching Everglades National Park at the tip of the peninsula.

In the 21st century, the recreational attractions in the approximately 1.4-million-acre Everglades National Park remain largely unchanged. Most of the park’s roughly one million visitors are daytime sightseers, although a significant number of tourists overnight in the park’s lodge or campground at Flamingo or boat out to and rough it on a remote chickee (a thatched-roof platform on stilts) in the mangrove forests. For birders, the area’s 300 avian species, from pink flamingoes to the endangered Cape Sable seaside sparrow, are one of the park’s most striking features, with numbers reaching into the tens, sometimes hundreds, of thousands during the winter–early spring nesting season. This also is the most popular season, with mosquitoes at a minimum, for tourists, who are eager to catch a glimpse of alligators and American crocodiles, the latter of which are unique to Everglades National Park. Everglades has 156 miles of canoe and hiking trails and a 15-mile biking trail leading to an observation tower on the Shark Valley tram road. Visitors tour the waters primarily in canoes, kayaks, and captained pontoon motorboats. Sport fishing ranges from salt to fresh to brackish water and concentrates among the thousands of acres of shallow-water flats, mangrove islands, and channels. During open state season, recreational crabbing is allowed, offering stone crabs and blue crabs. Hiking trails wend through the park’s diverse landscape, including sawgrass marshlands, wet prairies, pine flatlands, palmetto scrubland, and hardwood hammocks, where tourists can see wild orchids, bromeliads, the smooth-barked gumbo limbo tree, and the large golden silk orb-weavers (the largest nontarantula spiders in North America). Popular recreations in the larger Everglades, airboating and swamp-buggy rides are prohibited activities in the park.

JACK E. DAVIS

University of Florida

Ernest F. Coe, Landscape Architecture (October 1936); Jack E. Davis, An Everglades Providence: Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the American Environmental Century (2009); Everglades National Park, www.nps.gov/ever; Everglades National Park Information Page, www.everglades.national-park.com/info.htm.

Evert, Chris

(b. 1954) TENNIS PLAYER.

Chris Evert is the most successful woman tennis player to come from the South, and during a two-decade career she established herself as one of the greatest women athletes of the 20th century. In 1985 the Women’s Sports Foundation honored her as the Greatest Woman Athlete of the previous quarter century. When she retired from professional competition in 1989, she had 157 singles titles and 8 doubles titles.

Born 21 December 1954 in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Christine Marie Evert was the daughter of James Evert, a professional tennis teacher at Holiday Park Tennis Center in Fort Lauderdale. She began hitting tennis balls against the walls at age six, and her father was soon giving her intense lessons as part of a middle-class family where tennis was an everyday affair. Evert and her sister became professional tennis players, and her brother played intercollegiate college tennis at Auburn. Chris Evert won her first competitive play at age 10, and at age 15, at the Carolinas Tournament in 1970, she upset Margaret Court, then the top-ranked women’s tennis player. Within a year she had won the Virginia Slims Master’s Tournament, become the youngest woman selected for the U.S. Wightman Cup team, and competed in her first U.S. Open tournament. After graduating from St. Thomas Aquinas High School in Fort Lauderdale in 1972, she declared her professional status as she turned 18. By 1974 she had claimed the top ranking in women’s tennis.

Evert had more than 1,300 match wins. Her career doubles record was 117–39. Evert won her first Grand Slam singles title in 1974 and won 55 consecutive matches that year. In her career, she won 18 Grand Slam singles championships. She captured the French Open seven times (1974, 1975, 1979, 1980, 1983, 1985, 1986), the U.S. Open six times (1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1982), Wimbledon three times (1974, 1976, 1981), and the Australian Open twice (1982, 1984). She was the world’s top ranked player from 1974 to 1979. With her great success, she gained the nickname “Ice Maiden of Tennis” for her domination of the sport and her calm, focused manner while playing. The Associated Press named Evert female athlete of the year four times and Sports Illustrated honored her as sportswoman of the year in 1976. She served as president of the Women’s Tennis Association from 1975 to 1976 and from 1983 to 1991.

Evert’s success paralleled the rise of women’s tennis in the late 20th century. Television regularly broadcast woman’s tennis, making her a well-known celebrity and popularizing her baseline game and two-handed backhand for the next generation of women players.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Johnette Howard, The Rivals: Chris Evert vs. Martina Navratilova: Their Epic Duels and Extraordinary Friendship (2006); Chris Evert Lloyd, with Neil Amdur, Chrissy: My Own Story (1982); Betty Lou Phillips, Chris Evert: First Lady of Tennis (1977).

Favre, Brett

(b. 1969) FOOTBALL PLAYER.

Brett was widely thought to be the most accomplished quarterback in professional football in the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century. While playing for the University of Southern Mississippi in 1990 Brett Favre was involved in a terrible auto crash after which a large section of his intestine had to be removed. Five weeks later he returned to the lineup to defeat heavily favored Alabama. Crimson Tide Coach Gene Stallings declared, “You can call it a miracle or a legend or whatever you want to, I just know that on that day, Brett Favre was larger than life.” It would not be the last time that would be said.

Brett was born in 1969 to a family in Kiln, Miss., with a Cajun and Choctaw background. Coached in high school by his father, he played quarterback in a run-dominated offense that saw him passing very little. This probably contributed to the fact that he was offered only one scholarship to a Division I school, the University of Southern Mississippi—and that was to play defensive back. Though he was deep in the quarterback depth chart, he was brought in during a 1987 game against Tulane. He threw two touchdown passes and led the team to a win, all the while nursing a massive hangover.

Favre partied extremely hard in college and had a child with his then-girlfriend Deanna (whom he met in Catholic Sunday school when he was seven and later married). He did manage to earn a degree in special education, and his aptitude in that field later demonstrated itself in his charitable foundations and in the time he takes with children.

He was not highly sought after in the NFL draft, even given his college success. Eventually the Atlanta Falcons picked him up, but they had no real use for a hard-drinking Cajun with a laser gun for an arm. They traded him in 1992 to Green Bay, where general manager Ron Wolf and coach Mike Holmgren saw something, although they were not quite sure what.

During his first several seasons, Favre infuriated fans and coaches with his passes that regularly broke fingers—often those of the opposing team. Gradually Holmgren calmed Favre down and built a team around him that was able to win Super Bowl XXXI (1997), while his quarterback garnered three consecutive MVP awards. During this time Favre went into voluntary rehabilitation for an addiction to prescription painkillers. This was highly successful and the addiction never returned. In 1996 he married his college girlfriend, Deanna, and the couple has two daughters.

Mike Holmgren departed in 1998, and, though the Packers were never able to duplicate their success under him, Favre went on to have a career as one of the best quarterbacks in NFL history and the holder of nearly every major record that a quarterback can possess. Most notable among these are more than 460 touchdowns, 64,000 yards passing, 5,600 pass completions, and, in true Favre style, more than 300 interceptions. Most astonishing, however, is his record of more than 287 consecutive games started, a statistic that compares to Cal Ripken’s streak in baseball, especially at one of the most demanding positions in sports.

Perhaps his most special game came in Oakland in 2003. One day after his father was killed in an auto crash, and with his family’s encouragement, he decided that he could not let his team down and that his father would have wanted him to play. Before a nationwide audience on Monday Night Football, Favre threw for 4 touchdowns and 399 yards, winning 41–7. There was not a dry eye in the country after that game, and even the Raider Nation gave him a standing ovation.

Though Green Bay is in the heart of the Northwoods, Brett Favre never lost his southern manners and appeal. Green Bay and Wisconsin took him in as a favorite son. In a place where the average temperature high is below freezing for several months at a time, Brett from Kiln, Miss., was known for winning the cold-weather games. He said he did not like the cold much, but his play always seemed to give lie to the statement. In the off-season he would return to his farm in Mississippi with his family and every season be right back in Green Bay. That is, until 2008. After 16 seasons in, Favre retired and, like many high-level athletes today, subsequently unretired. Management, it seemed, was unimpressed. What happened next was unthinkable to many Packers fans. Brett Favre was traded to the New York Jets.

Now, if Brett Favre in Green Bay seemed strange (though it appeared the most natural thing in the world after a few years), the Kiln native under the scrutiny of the New York fans and press seemed more than incongruous. Nevertheless, he succeeded there as well, taking a team that was 4–12 in 2007 to the brink of the playoffs, while the Packers, whom he took to the NFC championship game that year, finished below .500 in 2008. Favre retired again after the 2008 season, but then came out of retirement in 2009 to lead the Minnesota Vikings to the NFC championship game, where they lost to the New Orleans Saints 31–28 in overtime.

Favre has exported his southern bonhomie on a national scale, though on a quieter level than Terry Bradshaw, and with less commercial savvy than Peyton Manning. He comes across to people as genuine, and his work ethic and endurance under trying conditions are things that can be embraced all over the country, from southern Mississippi to the frozen tundra of Green Bay, from the media center of New York City to, perhaps finally, Minnesota’s Twin Cities.

DONALD S. PRUDLO

Jacksonville State University

Deanna Favre, Don’t Bet Against Me (2007); Sam Lucero, Catholic News Service (25 October 2007); Bonita Favre and Brett Favre, Favre (2004); Gary D’Amato, Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel (17 October 2005); Jimmy Traina, Sports Illustrated (5 October 2002).

Flora-Bama Lounge and Package

It is not often that a bar becomes a cultural attraction beyond the distance one of its patrons can (or should) safely drive after closing time, but the Flora-Bama Lounge and Package is one bar that has become just that. Billed as “The Last American Roadhouse,” it has been featured on local and national television, written up in a variety of publications, and immortalized in the music of Jimmy Buffet. It is dear to the hearts of the many who have enjoyed its hospitality and an imagined destination in the minds of those who leave their recliners only for trips to the refrigerator.

To have a roadhouse one needs a road, so there was no Flora-Bama until the highway between Orange Beach, Ala., and Perdido Key, Fla., was completed in 1962. Two years later the bar and package store was built, just on the Florida side of the border, to take advantage of the Sunshine State’s more liberal liquor laws. But because the establishment butted right up against Alabama, the motto “Let’s do it on the line” was a natural.

The early days were rough. A suspicious fire burned down the first Flora-Bama, but it was rebuilt and, being almost the only place to get a beer on that lonely stretch, it became a popular watering hole for locals and visitors.

In 1978 two events coincided to make the Flora-Bama what it is today. Joe Gilchrist and Pat McClellan bought the place and made music an essential part of the “Bama” entertainment. That same year an article in the New York Times (“Todd and Stabler Offseason Game: Living It Up on ‘Redneck Riviera’”) highlighted the Flora-Bama as the home of the “midnight rambler and honky-tonk rounder.” The rest, as they say, is history.

With Gilchrist tending bar and musicians making their music, the Flora-Bama evolved into a go-to place and the epicenter of the Redneck Riviera. Eventually it grew into a sprawling complex of bars and stages where bands played to packed audiences that consisted of bankers, bikers, and all the variety in between. It is a place where, according to one observer, “you can holler ‘Bubba’ and 15 people will respond.” University of Alabama football hero and All-Pro quarterback Kenny Stabler called it “the best watering hole in the country,” and so far no one has challenged him or argued otherwise.

As beach communities grew up around it, the Flora-Bama became a major tourist attraction, though one where attractions were typically Flora-Bama. The year kicks off in January with the Polar Bear Dip, where alcohol-insulated patrons take to the frigid Gulf. Spring is brought in with the Annual Interstate Mullet Toss, and in the fall there is the Frank Brown International Songwriter’s Festival, which honors a legendary bouncer and celebrates the Bama’s reputation as a place where entertainers can play their own compositions and not be forced to cover “popular” hits.

In September 2004 the Flora-Bama was almost lost when Hurricane Ivan roared ashore, destroying or damaging most of the building and sweeping away scores of bras that hung from the ceiling and classic inscriptions that decorated the restroom walls. For nearly a year, fans waited patiently while temporary structures, many of them trailers, were brought in and set up in a fashion reminiscent of the warrenlike arrangement of the original complex. When all was in place (and, in some cases, even before), the Flora-Bama was open for business.

And what a business it is. Events like the Mullet Toss yearly break attendance records, beer sales continue to climb, while legends and lies about what was done on the line are passed about as the gospel truth.

Meanwhile, after a lot of legal wrangling, the Escambia (Fla.) County Board of Adjustments agreed to a variance that would allow the Flora-Bama to be rebuilt in a way that the owners promised would be true to “the style, structure and mystique of the pre-Ivan Flora-Bama for generations to come.” The management warned friends that “it will be tricky to rebuild, because you have been keeping us as busy as ever,” but no one complained. That’s what is to be expected if you are “the Last American Roadhouse.”

HARVEY H. JACKSON III

Jacksonville State University

Alan West Brockman and Joe Gilchrist, The Last American Roadhouse: The Documentary of the Flora-Bama (film, 2006); Ryan Dezember, Mobile Press-Register (27 April 2008); Robert F. Jones, Sports Illustrated (19 September 1979); Harris Mendheim, director, Mullet Men: Second Place Is the First Loser (film, 2000); Howell Raines, New York Times (21 June 1978); Ken Stabler and Berry Stainback, Snake: The Candid Autobiography of Football’s Most Outrageous Renegade (1986); Michael Swindle, Mulletheads: The Legends, Lore, Magic, and Mania Surrounding the Humble but Celebrated Mullet (1998), Village Voice (13 May 1997).

Fourth of July

The Fourth of July celebrates the independence of the United States and has been an important holiday in the South since the American Revolution. Typical activities have included parades, picnics, patriotic speeches, baseball games, ceremonies honoring veterans, the reading of the Declaration of Independence, and assorted community events. As elsewhere in the nation, fireworks have long been a part of the celebration, both in community-sponsored large fireworks shows and privately, among individuals. City ordinances control fireworks in most cities, but the familiar roadside fireworks stands pop up on edges of cities in early summer. Williamsburg, Va., with its pronounced colonial history focus, sponsors its Prelude to Independence beginning in May, with 18th-century cannons fired and bells rung at the College of William and Mary and at historic Bruton Parish Church. In addition to these historic spots, independence activities take place at special sporting events, such as stock races, including Daytona’s Firecracker 400 in Florida.

The history of the Fourth of July in the South reveals it to have long been a contested holiday, focusing on issues of sectionalism and race relations. In the early 19th century, the Fourth of July was a vital commemoration that promoted national feeling in the young republic. A Raleigh, N.C., orator in 1851 praised the Union on the holiday and its “importance to the maintenance of our liberties, and the safety, peace and prosperity of the whole country.” This nationalist spirit was expressed, though, in local and regional contexts. For antebellum white southerners, the Declaration of Independence and the Fourth of July did not relate to issues of slavery but of compromise and union. With the beginning of the Civil War, few southern communities marked the day, but the Confederacy continued to lay claim to the heritage and heroes of the American Revolution and saw the South as the champion of the legacy associated with the Fourth. After the war, southern states rejoined the Union, but white southerners until the turn of the 20th century refused to commemorate the Independence Day. A Wilmington, N.C., newspaper said the Fourth “should be passed by our people in dignified silence.”

Black southerners, however, embraced the Fourth of July and its key document of the Declaration of Independence as symbols of their new freedom. Historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage notes that southern blacks “virtually laid claim to Independence Day.” African American memoirist Mamie Garvin Fields recalled of her Charleston childhood in the 1890s that “the oldtime Southerners,” meaning whites, saw the Fourth as a “Yankee holiday and ignored it.” For her and other blacks, though, she said, “Oh, my, but the Fourth was a big day.” During Reconstruction, blacks occupied the South’s public spaces for their joyous celebrations of American nationalism. Parades, military bands, and African Americans in militia uniforms proclaimed the new power and position of African Americans in the postwar South. But these rituals stirred white anxieties and sometimes led to white violence against blacks. As late as the 1890s, though, blacks in Richmond, Va., celebrated the holiday with parades and military musters at the state Capitol and even staged events at the Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue.

The centennial celebration of American Independence in 1876 was a notable event in North-South reconciliation that would lead to diminished African American participation in civic celebrations of the holiday. Northern celebrations often omitted a role for blacks—thus denying a fundamental meaning of the Civil War and the extension of the ideals of the Declaration of Independence—but highlighting the white South’s historic role in founding the nation. White southerners fought in the Spanish American War, reviving a sense of American patriotism in the region and leading to their increased honoring of the Fourth. Patriotic organizations like the Daughters of the American Revolution were active in the South from the Progressive Era onward, promoting the rise of a new patriotism that emphasized the common Revolutionary heritage of North and South. Whites now held whites-only civic ceremonies, with black commemorations moved to separate locations in black neighborhoods. Historian Fletcher M. Green could still observe, though, that as late as the 1950s, “little attention is paid to July Fourth by the people of North Carolina,” although he referred only to whites in that conclusion.

The bicentennial celebration of American independence in 1976 led to a new embrace of the Fourth of July by southern communities. The desegregation of southern public facilities in the 1960s promoted the most integrated and enthusiastic celebration in the region’s history. Bicentennial events, programs, and projects included restoration of historic districts and downtown areas, the commissioning of musical events with patriotic themes, construction or expansion of civic buildings and museums, and the staging of festivals and exhibits around historical themes. The American Revolution Bicentennial Administration provided public funding and general coordination, with state commissions active throughout the South.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (2005); Hennig Cohen and Tristram Potter Coffin, eds., The Folklore of American Holidays (3rd ed., 1997); Matthew Dennis, Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar (2002); Jane M. Hatch, The American Book of Days (3rd ed., 1978).

Gibson, Althea

(1927–2003) TENNIS PLAYER.

Althea Gibson was the first African American to win a Grand Slam major tennis tournament, becoming known as “the Jackie Robinson of tennis” for her achievement. Born to sharecropping parents in Silver, S.C., Gibson grew up in Harlem, beset by poverty and behavioral difficulties but excelling in athletics. Walter Johnson, a Virginia physician who had long worked to develop young black tennis players, became her mentor. After further training in Wilmington, N.C., she won the first of her 10 national championships in American Tennis Association all-black tournaments. In the segregated world of tennis then, she was kept out of tournament competition with whites until breaking the color barrier in 1950, playing in the U.S. championship at Forest Hills, N.Y. In the same year, she graduated from Florida A&M University, having played basketball as well as tennis.

Althea Gibson, “the Jackie Robinson of tennis,” 1956 (Fred Palumbo, photographer, Library of Congress [LC-USZ62-114745], Washington, D.C.)

Gibson won the Italian championship (1955), the French championship in singles and doubles (1956), and the Wimbledon championship in doubles (1956) and singles (1957). The latter prestigious win earned her a ticker-tape parade in New York City, and in her breakout year of 1957 she was ranked No. 1 in world tennis and the Associated Press named her female athlete of the year. She won the Wimbledon singles and doubles titles in 1958 and defended her singles title at the U.S. championship the same year. Women’s tennis was entirely amateur in Gibson’s era, and she retired in 1958, playing in exhibition tours thereafter, including working with the Harlem Globetrotters. Gibson recorded an album, Althea Gibson Sings (1958), and published an autobiography, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody (1958).

The International Tennis Hall of Fame inducted Althea Gibson in 1971. Four years later she became the New Jersey Commissioner of Athletics. She worked in other government positions as well but suffered a stroke in 1992. She died in 2003 in East Orange, N.J. She had long remembered receiving the Wimbledon trophy and shaking hands with Queen Elizabeth II, thinking that experience “was a long way from being forced to sit down in the colored section of the bus going into downtown Wilmington, N.C.”

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Althea Gibson, with Richard Curtis, So Much to Live For (1968); Billie Jean King, with Cynthia Starr, We Have Come a Long Way: The Story of Women’s Tennis (1988); George Vecsey, New York Times (29 September 2003).

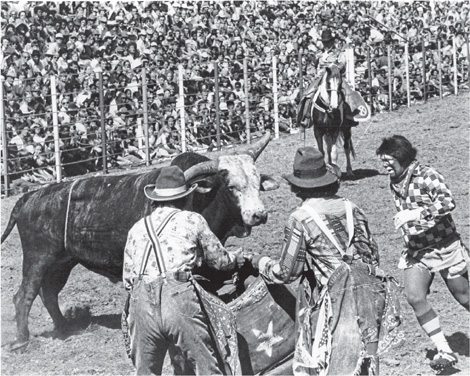

Gilley’s

Gilley’s, in Pasadena, Tex., was founded by Sherwood Cryer as “Shelly’s.” Its success, like its present name, dates from 1971, when Cryer went into partnership with Mickey Gilley, a country music singer and piano player once probably best known as Jerry Lee Lewis’s cousin. Billed at one time as “the World’s Largest Saloon” (it could accommodate 4,500 customers), it eventually offered, besides the traditional drinking and dancing, such challenging entertainments as a punching-bag machine and “El Toro,” a mechanical bull for customers to ride. Dancing at the club was to music supplied by Gilley, by the house band (the Bayou City Beats), or by visiting country music entertainers, and it included group dances such as the Cotton-Eyed Joe (punctuated with rhythmic chants of “Bullshit!”) and the schottische.

Despite these attractions, Gilley’s was little known outside the Houston area, except in country music circles, before 1978, when Esquire published an article by Aaron Latham on the club and some of its patrons. Latham’s article was accompanied by a photographic feature on designer Ralph Lauren’s new line, “embracing the rugged natural look of the American cowboy.” When the movie Urban Cowboy, starring John Travolta, was actually filmed in Gilley’s, scores of more or less frankly imitative establishments sprang up across the country. These “cowboy” bars sometimes replaced discos that had been inspired by Travolta’s performance in Saturday Night Fever and catered to much the same clientele, even more urban and less plausibly cowboy than the young oil workers Latham had chronicled. The most bravura of these new establishments was also in Texas, a Fort Worth club called “Billy Bob’s” that offered live bull riding in place of Gilley’s machine-simulated version. (Rumors that a patron had been stomped and gored did not hurt at all.) Billy Bob’s was even larger than Gilley’s, and on one occasion Merle Haggard treated all 5,095 customers to drinks.

The era of “Texas chic” soon faded, but not before Gilley’s had become a major tourist attraction with its own magazine, its own brand of beer, and complete line of souvenirs. Mickey Gilley himself had become a major country music singer with a number of hits to his credit, including “Don’t the Girls All Get Prettier at Closing Time”—a traditional number at the club.

Southerners themselves have often collaborated in—and occasionally profited from—the marketing of the South. But the story of Gilley’s reflected a new development in the nation’s old, on-again/off-again love affair with the South. Gilley’s represented, and Esquire and Hollywood marketed, a blue-collar South newly popular in the 1970s, populated by the same good old boys (and girls) whom the mass media had generally portrayed a decade earlier (in such movies as Easy Rider and Deliverance, for instance) as vicious rednecks. The increasing national respectability of their music, the popularity of Burt Reynolds and the Dukes of Hazzard, and, not least, the “Urban Cowboy” phenomenon—all attest to a metamorphosis that was one of the stranger aspects of a strange decade. This attention presaged a rising popular culture interest since then in rednecks and other varieties of white working-class southern culture. The original Gilley’s, meanwhile, was demolished in 2006, but a new Gilley’s—with 91,000 square feet of entertainment and meeting space—opened in 2003, complete with “El Toro.”

JOHN SHELTON REED

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Bob Claypool, Saturday Night at Gilley’s (1980); Robert Crowe and Gregory Curtis, Texas Monthly (November 1998); Aaron Latham, Esquire (September 1978).

Graceland

Graceland, formerly the estate of an aristocratic Memphis family, became the home of the rock and country icon Elvis Presley from 1957 until his death in 1977. Graceland has since ceased to be a private residence and now enshrines the memory and meaning of Elvis. Located off Highway 51, about eight miles from downtown Memphis, Tenn., Elvis’s former home is a favored destination for thousands of fans every year. The largest single gathering takes place on August 18, the anniversary of Elvis’s death. Thousands of the curious, the contemptuous, and the utterly worshipful make a pilgrimage that involves tours of the home, candlelight vigils, and a slow procession by the grave of the King of Rock and Roll.

Elvis purchased the estate for himself and his parents, Vernon and Gladys Presley. Frequent renovations completely transformed the colonial-style estate. Elvis had wanted, first, an enlarged bedroom and living area for his mother and, secondly, requested that a soda fountain, “a real soda fountain with cokes and an ice cream thing,” be installed in the kitchen.

Ironically, Elvis purchased Graceland to find relief from the constant attention of his persistent fans. The mansion sat on a little over 13 acres with a lush, forested park stretching from the front door down to the iron gates and stone wall that surrounded the property. Graceland, however, became so closely identified with its owner in large part because fans, and Elvis himself, worked to prevent the home from becoming a truly “private” residence. The large stone wall offered devoted fans the opportunity to mark, stencil, and chalk their love to Graceland’s owner. Presley himself seemed to invite such attention, at one point stringing bright blue Christmas lights from Highway 51 all the way up to the mansion’s front steps. Presley also made it a practice to dramatically leap the walls and sign autographs at least once a day. During his frequent absences, the gates opened between 8:00 A.M. and 5:00 P.M. and fans were allowed to walk the grounds and even look in the windows.

Elvis, and his heirs, emphasized the rural past of Graceland, hoping to play on both Presley’s southern roots and the “cowboy” imagery he dearly loved. Elvis himself attempted to build on this mythic image in 1967 when he purchased more than 160 acres south of Memphis off of Highway 51. Purchasing innumerable pickup trucks, horses, and cattle, as well a trailer for himself and Priscilla, he named the spread “The Flying G Ranch” (the “G” maintaining the connection to Graceland).

Following Elvis’s death, Graceland underwent extensive renovations in 1980–81 under the guidance of Priscilla Presley. A restaurant and hotel complex now sits across the highway from the mansion, boasting an enormous gift shop containing Elvis memorabilia of every description. Today, a bus carries visitors from the hotel-restaurant complex, through the front gates and up to the very steps of the mansion, much as lucky fans who crowded outside the gates in the 1950s and 1960s would occasionally be taken in a large hot pink jeep to the house to have dinner with Elvis, his family, and friends.

W. SCOTT POOLE

College of Charleston

Peter Guralnick, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley (1994), Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley (1998); Karal Anne Marling, Graceland: Going Home with Elvis (1996).

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Federally mandated in 1934 to be one of three major units of the National Park Service in southern Appalachia, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park incorporates 814 square miles and encompasses most of the Great Smoky Mountains on the North Carolina–Tennessee border. The park incorporates the high-elevation ridgeline as well as the side ridges and valleys of the Smokies, a spur range of the Blue Ridge (the latter courses in a southwestward direction from south-central Pennsylvania to northern Georgia). Great Smoky Mountains National Park was linked with Shenandoah National Park, located in a section of the Blue Ridge in northern Virginia, by means of the Blue Ridge Parkway, a 469-mile federal scenic road that traverses southward along the crest of the Blue Ridge and various spur ranges before ending in the Smokies. These three units of the National Park Service were initially promoted in the 1920s by the automobile and tourism industries, and all three would receive extensive federal support during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. While the various properties acquired for the establishment of Great Smoky Mountains National Park were purchased with financial donations from the citizens of North Carolina and Tennessee and by philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr., infrastructural projects within the park were primarily funded by the New Deal programs of the Roosevelt administration.

The park offers numerous recreational activities. Most popular is auto touring, owing in part to the fact that the park has never charged an entrance fee. Each year millions of visitors drive on the Newfound Gap Road (U.S. Highway 441), which bisects the park, and on the Little River Road and the Cades Cove Loop Road to experience panoramic vistas of mountains and forests and to access high elevation sites (such as Clingman’s Dome, at 6,643 feet above sea level). Additionally, the park offers numerous opportunities for nature observation—of wildflowers, wildlife (especially black bear, white-tailed deer, and elk—the last-named species having recently been reintroduced into the Smokies), and other natural entities (such as the phenomenon of the synchronous fireflies at Elkmont). Other recreational activities within the park are bicycling (particularly in Cades Cove), fishing (in approximately 700 miles of streams, for native brook trout as well as for introduced brown and rainbow trout), hiking (on more than 800 miles of trails, including a 70-mile stretch of the Appalachian Trail), horseback riding (on more than 500 miles of trails allowable for horses), picnicking (at 11 maintained picnic areas), and camping (at more than 100 backcountry campsites or shelters accessed via hiking or horseback as well as at 10 developed campgrounds established for tents and recreational vehicles). Some people opt to make the steep trek up Mount LeConte to stay overnight at LeConte Lodge, originally built in the 1920s.

The park operates several historical exhibitions, most notably the Mountain Farm Museum (behind the Oconaluftee Visitor Center) in North Carolina, and, in Tennessee, the collection of 19th-century buildings in Cades Cove (including log and frame houses, two churches, and a mill). Structures that predate the park are also preserved, on the North Carolina side of the park, in Cataloochee Valley (which features, among other buildings, a church, a log cabin, and a frame house), and, in Tennessee, along the Old Settlers Trail (which is routed past numerous old home sites). The park maintains a total of 80 historical buildings in all.

Information or assistance from park rangers and other park staff may be obtained at campgrounds, at certain historical exhibits, as well as at three visitor centers (Sugarlands and Cades Cove Visitor Centers in Tennessee and Oconaluftee Visitor Center in North Carolina).

For the unparalleled ecological diversity it harbors within its boundaries, Great Smoky Mountains National Park was designated an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983, and a Southern Appalachian Biosphere Reserve in 1988. The Great Smoky Mountains Association, a nonprofit educational organization, cosponsors the Great Smoky Mountains Institute at Tremont, which is operated inside the park to foster wider public appreciation for the park’s natural and cultural history.

TED OLSON

East Tennessee State University

Michael Frome, Strangers in High Places: The Story of the Great Smoky Mountains (1994); Great Smoky Mountains Association, Hiking Trails of the Smokies (2003); Daniel S. Pierce, The Great Smokies: From Natural Habitat to National Park (2000); Michael Ann Williams, Great Smoky Mountains Folklife (1995).

Hamm, Mia

(b. 1972) SOCCER PLAYER.

Mariel Margaret “Mia” Hamm was a crystallizing figure in the growth of women’s soccer in the United States. Born 17 March 1972 in Selma, Ala., Hamm was the daughter of an Air Force officer and played soccer while growing up on military bases in Texas, Virginia, and Italy. She played for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the Tar Heels won four National Collegiate Athletic Association women’s soccer championship titles in five years while she played there, earning Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) female-athlete-of-the-year honors in 1993 and 1994. When she graduated, she held ACC records in goals (103), assists (72), and total points (278).

Hamm began playing on the United States women’s national soccer team at age 15, and at age 19 she was the youngest American woman to win a World Cup championship. She competed for the women’s national team for 17 years, and the team won the gold medal at the 1996 and 2004 Summer Olympics. The Federation Internationale de Football Association named her world player of the year in 2001 and 2002. Soccer USA named her female athlete of the year five times (1994–98). Hamm retired from soccer competition after the 2004 Olympics, having scored 158 goals in international competition, a record for the sport of soccer. In 2007 she was voted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame.

Hamm grew up in the aftermath of Title IX’s mandate for gender equality in sports, and she made use of new resources that enabled her to train and play competitively in route to becoming a world-class athlete. She then embodied the possibilities of athletic achievement for young women and spurred interest in soccer throughout the nation.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Mia Hamm, Go for the Goal: A Champion’s Guide to Winning in Soccer and Life (2007); Charles Maher, in Women and Sports in the United States: A Documentary Reader, ed. Jean O’Reilly and Susan K. Cahn (2007), USA Today (18 January 2008).

Hilton Head Island, South Carolina

As forested refuge for nomadic Indian tribes, as the site for 17th-century Spanish and French fortifications, and as the location of antebellum Sea Island cotton plantations, Hilton Head Island has lured people through its climate and its geographic diversity.

Now one of the South’s most famous resort areas, Hilton Head had historic significance in the 19th century. On 7 November 1861, 17 Union warships blocked South Carolina’s Port Royal Sound, capturing the Confederate stronghold of Fort Walker on the island. The Port Royal anchorage remained the principal base of federal naval operations for the duration of the war, and Hilton Head’s Port Royal Plantation, quartering some 30,000 troops, was transformed into a boomtown, complete with hotels and a theater. Along with other southern sea islands, Hilton Head became the focus for a social and agrarian experiment, in which large plantations and town property were claimed by the federal Treasury Department and redistributed to freedmen.

Called a “dress rehearsal for Reconstruction,” the Port Royal experiment influenced the formation of federal policy concerning the status of emancipated slaves. Its schools, military training, and wage labor programs acted as a proving ground for freedmen and provided experience for postwar Reconstruction leaders such as General O. O. Howard, head of the Freedman’s Bureau, and Congressman Robert Smalls. Many of the freed slaves who remained on Hilton Head Island were of Gullah descent and maintained their existence on the island with subsistence farming.

Soon, however, prosperous northern investors were attracted to the Sound. Huge tracts of land, and sometimes whole islands, were purchased for use as hunting preserves and winter havens. The largest of South Carolina’s barrier islands—12 miles long and covering about 42 square miles—Hilton Head escaped sole proprietorship and became instead a popular combination of resort and residential development.

Gulf breezes keep temperatures on the island at a semitropical 60° to 80° range throughout the year. Many visitors to the island are attracted by its pristine beaches and ocean activities, such as waterskiing, parasailing, surfing, sailing, scuba diving, fishing and crabbing, and dolphin cruises. But Hilton Head’s attractions are not just along the shoreline; nature lovers go to enjoy the island’s numerous nature preserves. The ocean and networks of freshwater lagoons, meadows, forest area, and marshland support some 260 varieties of birds, as well as bream, bass, and blue marlin. Sea oats and palmetto share the landscape with magnolia, pine, and live oak. These nature preserves offer visitors and residents opportunities for fishing, canoeing, kayaking, hiking, biking, bird watching, and horseback riding.

Cultural activities and events also abound at Hilton Head; historic tours and Gullah heritage tours are popular, and numerous art galleries and cultural exhibits attract museum-goers. The island also has its own orchestra, which performs regularly. Avid shoppers enjoy frequenting plentiful boutiques and art galleries (more than 200) and both indoor and outlet malls.

Hilton Head offers its more than 2.5 million annual visitors an abundance of recreational diversity. There are 8 marinas, 23 golf courses, and more than 300 tennis courts on the island. Seafood restaurants are popular among visitors and residents alike. Accommodations range from hotel rooms to oceanfront villas with names like Bay-berry Dune and Xanadu. Abounding in secluded white sand beaches and quiet nature trails but only hours from the urbane charm of Charleston, Hilton Head represents a fusion of society and serenity that has a characteristically southern flavor.

ELIZABETH M. MAKOWSKI MARY AMELIA TAYLOR

University of Mississippi

Michael Danielson and Patricia Danielson, Profits and Politics in Paradise: The Development of Hilton Head Island (1995); Guion Griffis Johnson, A Social History of the Sea Islands (1930); Hilton Head Island Chamber of Commerce, www.hiltonhead island.org; Willie Lee Rose, Rehearsal for Reconstruction: The Port Royal Experiment (1964); Southern Living (April 1982); David D. Wallace, South Carolina: A Short History, 1520–1948 (1961).

Hooters

Ask most males why they eat at a Hooters restaurant and they will likely tell you that the chicken wings are delicious. Although that certainly may be true, others would contend that the siren call that attracts large numbers of men to Hooters is not related to the food. Established in 1983 in Clearwater, Fla., Hooters of America, Inc. has grown from a single establishment in the Sunshine State to a chain of some 450 locations throughout the world, including international branches in Greece, Singapore, Korea, England, and Australia, to name a few. According to Hooters’ corporate history, more than 68 percent of Hooters patrons are male and between the ages of 25 and 54. While the restaurant does not cater to families, it admits that some 10 percent of its patrons are children.

The original Hooters Restaurant in Clearwater was the brainchild of Alisa Lamellae, who found cheap land on which to build—a former dumpster-washing facility. The original concept for Hooters was more of a bar than a full-service restaurant. The scantily clad servers were always part of the equation, though. In 1984 Robert H. Brooks and a group of Atlanta investors bought franchise rights outside of the six-county Tampa area. Brooks and his investors often clashed over leadership of the chain until they bought out the original owners with $60 million and limited franchising rights in exchange for the Hooters trademark.

Under Brooks’s leadership, Hooters grew exponentially (corporately speaking), establishing a presence in every state and in 20 countries. He explained Hooters’ success as “Good food, cold beer, and pretty girls never go out of style.” Brooks did, however, assert that he never realized what the owl symbolized in the Hooters logo. In 2004 Hooters Airline tried to offer air travelers the same wholesome goodness that Brooks asserted one could find in the restaurants. Flight attendants wore the now familiar short orange shorts and snug fitting white tank tops. But the airline ceased operations in 2006, citing the high cost of jet fuel.

In 1991 the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) accused Hooters of sexual discrimination against men because all of the company’s servers were women. Hooters had made no claim to the contrary, but the company addressed the accusations by organizing a “100 Hooter girl march” on Washington, D.C., while encouraging Hooters patrons to conduct a postcard campaign in support of the chain to Congress. The EEOC never brought suit on the matter. Six years later, in 1997, men in Chicago and Maryland filed class action lawsuits against Hooters, claiming that the restaurant chain discriminated against men in hiring servers. The matter was settled out of court. Hooters vigorously defends the use of the female form in restaurants, asserting without a hint of irony on its corporate Web site that “the Hooters girl is as socially acceptable as a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader, Sports Illustrated swimsuit model, or a Radio City Rockette.”

Hooters maintains, however, a strong presence in the male-oriented, sports bar, chicken wings restaurant scene and has increased that role by sponsoring NASCAR racing teams and hosting the Annual Hooters International Swimsuit Pageant, which chooses Miss Hooters International from among the chain’s Hooters Girl employee population.

For all its assertions of a wholesome, All-American, atmosphere, Hooters remains a point of contention between those who support the chain and its image and those who feel that it is an exploitation of the female form.

GORDON E. HARVEY

Jacksonville State University

Dean Foust, Business Week (13 June 2005); Hooters Corporate History, www.hooters.com/about; Douglas Martin, New York Times (18 July 2006).

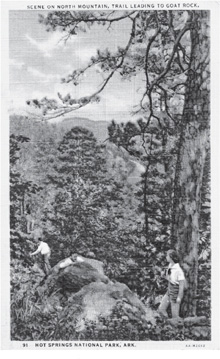

Hot Springs National Park

Forty-seven hot springs flowing from the slope of Hot Springs Mountain in the foothills of Arkansas’s Ouachita Mountains gained much attention in the early 19th century as a treatment for rheumatism and other ailments. Today, these naturally occurring springs serve as the centerpiece of Hot Springs National Park, one of the state’s most popular tourist destinations.

Archaeological and other historical evidence suggests that Native Americans bathed in Hot Springs Creek prior to the arrival of Europeans. Before the Louisiana Purchase, the area surrounding the springs remained a virtually uninhabited wilderness; after that time, the thermal waters gained a widespread reputation for their healing, therapeutic qualities.

Early on, visitors flocked to the area in search of a cure. For example, in the 1820s the Arkansas Gazette reported 61 people representing seven different states at the springs “for health and pleasure.” Belief in the thermal waters’ efficacy in treating rheumatism and paralytic afflictions caused the valley’s popularity to grow with each passing year.

In 1820 the Arkansas Territorial Assembly requested that Congress grant the site to the newly established Arkansas Territory, but Congress refused. Instead, on 20 April 1832, Congress created the Hot Springs Reservation by setting aside “four Sections of land including said Springs” for future use of the United States, making it the oldest area in the National Park System. This act intended to deny private landowner-ship within a mile of the springs, but the government failed to enforce the measure so the town continued to grow within the federally reserved area.

The uncertainty surrounding landownership in the area hindered progress. Hot Springs’ population increased little from the time of Arkansas statehood until the Civil War, reaching only 201 by 1860, but its fame as a health resort grew steadily. While the land dispute discouraged large investments or improvements for residents or visitors, a number of structures sprang up in the narrow valley alongside Hot Springs Creek. Bathing procedures remained primitive and visitors utilized crude facilities throughout the antebellum period.

Following the Civil War, the place took on an entirely different character. Numbers of tourists increased dramatically as patrons from all parts of the country poured in to spend their money. After 1869 the number of visitors grew by about 50 percent each year, and by the early 1870s Hot Springs enjoyed widespread popularity across the nation as a health resort. When Garland County was established in 1873, the city of Hot Springs became the county seat. The town included 24 commercial hotels and boardinghouses, with capacity of 1,500 to 2,000 visitors per day. After the U.S. Supreme Court finally vested title to the springs in the federal government in 1877 and allowed private ownership in the surrounding area, bathing facilities and services enjoyed even further expansion. The once sleepy little village rapidly acquired characteristics of a wide-open boomtown.

Vintage postcard of Hot Springs National Park (Charles Reagan Wilson Collection, Center for the Study of Southern Culture, University of Mississippi)

The government took an active interest in its Hot Springs Reservation in the late 19th century. Federal improvements helped transform the frontier town to a cosmopolitan spa: construction of a grand entrance to the Reservation, mountain drives, elaborate fountains, and an arch covering Hot Springs Creek along Central Avenue, all contributed to a more pleasing appearance. And government officials regulated activity involving the springs by establishing standards for bathing prices and related services.

For decades to follow, growth and development within the bathing industry paralleled growth and development of the city itself. Bathing reached a peak by the end of World War II, when over one million baths per year were provided to patrons. As the industry reached its zenith during the first half of the 20th century, luxury accommodations dominated the town’s landscape, and the city bristled with activity. The town gained a reputation as an entertainment-rich destination, complete with illegal gambling, thoroughbred racing, and an assortment of amusement parks. Everyone—movie stars, politicians, rich, poor, and even gangsters—frequented “The American Spa.” The town’s slogan, “We Bathe the World,” rang true.

In 1916 Congress established the National Park Service, and the Park Service assumed control of the Hot Springs Reservation. The reservation officially became Hot Springs National Park on 4 March 1921. A combination of factors resulted in the sharp decline of Central Avenue and its bathing industry by the 1960s: improved medical techniques, a general trend away from downtown shopping, and the elimination of gambling, all contributed to the downturn.

Hot Springs’ Bath House Row was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on 13 November 1974. The most ornate of the Central Avenue structures, the Fordyce Bath House, became the National Park’s visitor center, and only one of the of eight existing bathhouses continues to offer baths today. The remaining six facilities sit vacant. Now, as the reservation approaches its 175th anniversary, park officials plan to offer leases of the other structures to the private sector for renovation and development in an attempt to revitalize Hot Springs National Park’s world famous Bath House Row.

WENDY RICHTER

Ouachita Baptist University

Orval Allbritton, Leo & Verne: The Spa’s Heyday (2003); Dee Brown, The American Spa: Hot Springs, Arkansas (1982); Francis J. Scully, Hot Springs, Arkansas and Hot Springs National Park: The Story of a City and the Nation’s Health Resort (1966).

Johnson, Junior

(b. 1931) SPORTS CAR DRIVER AND MOONSHINER.

Robert Glenn “Junior” Johnson is the most famous resident of Ingle Hollow in Wilkes County, N.C. Neighbors used to admire him for his adeptness at outwitting and outmaneuvering tax agents on moonshine runs. Now they and fans throughout the South and the nation revere him for his accomplishments as a stock car driver.

Johnson’s father operated a still in Wilkes County, one of the most productive moonshine regions in the country. The size of his profit often depended on whether Junior could deliver the product to customers in nearby cities and towns without getting caught; so Junior learned to drive fast and skillfully, often evading would-be captors by implementing his “bootleg turn,” a technique that evolved into the “power slide” he later used as a stock car driver to maintain and accelerate speed coming out of turns on the racetrack. In 1955 agents caught him, not on a delivery, but standing in front of the still. He served just over 10 months in a Chillicothe, Ohio, prison.

At the time of his arrest, Johnson was already well on his way to becoming a successful stock car driver. He had won championships in the Sportsman and Modified classifications and, in 1955, captured the first of his seven Grand National victories. Ten years later he retired as a driver, having won the Daytona 500 and 49 other races. He was one of the sport’s most popular figures.

Beginning in 1965, Johnson hired drivers for his cars and, with employees like Bobby Allison, Cale Yarborough, and Darrell Waltrip, his success continued, with his drivers winning 139 races. Recognized as a master mechanic, Johnson worked as a consultant to General Motors while still operating from his home in Ingle Hollow, where he and his staff built parts, made repairs, and worked to keep the team’s cars among the fastest on the track. In 2007 Johnson teamed up with Piedmont Distillers in Madison, N.C., to begin making Midnight Moon, a small-batch moonshine made in the Johnson-family tradition.

Success has not separated Johnson from his heritage in the rural South. He is a prototypical good old boy who likes coon hunting and chicken farming. He even helped found the Holly Farms Chicken company in North Wilkesboro, N.C. Writer Tom Wolfe called him the “Last American Hero,” and Johnson’s neighbors would probably agree. His bootlegging days may be well past—even if his moonshining days are not.

JESSICA FOY

Cooperstown Graduate Programs Cooperstown, New York

Pete Daniel, Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s (2000); Larry Griffin, Car and Driver (April 1982); Charles Leerhsen, Newsweek (16 November 1981); Neal Thompson, Driving with the Devil: Southern Moonshine, Detroit Wheels, and the Birth of NASCAR (2006); Tom Wolfe, Esquire (March 1965).

Jones, Bobby

(1902–1971) GOLFER.

Born on 17 March 1902 in Atlanta, Ga., Robert Tyre “Bobby” Jones Jr. was a child prodigy at golf, studying under Stewart Maiden, a Scottish pro who worked at Atlanta’s East Lake course. Jones played in the 1916 U.S. Amateur Tournament when he was only 14 years old. He went on to win 13 major championships, culminating in 1930 with his sweep in a single season of the “Grand Slam of Golf,” which was then the championships of the British Amateur, the British Open, the U.S. Open, and the U.S. Amateur. New York City treated him to an enormous ticker tape parade that year, appropriate to one who had become a national hero. Later, he received a similar outpouring of affection from his hometown in Atlanta. At the height of his fame, at age 28, Jones announced his retirement. He returned to his law practice and business endeavors in Atlanta, starting a long involvement with the A. G. Spalding Company, making a series of instructional film shorts for Warner Brothers studios, and conceiving and assisting in the design of the Augusta National Golf Course in Augusta, Ga., home of the Masters Tournament.

Jones’s career reflected the rise of spectator sports in the South and the nation during the 1920s. Although golf was not as popular in the South as in the Northeast and on the West Coast, Jones nonetheless consciously worked to increase its popularity in his home region. He conceived the idea of the Augusta course, because “my native Southland, especially my own neighborhood, had very few, if any, golf courses of championship quality.” He regarded it “as an opportunity to make a contribution to golf in my own section of the country.”

Jones was frequently referred to as the embodiment of the southern gentleman. Journalist and commentator Alistair Cooke wrote that Jones was “a gentleman, a combination of goodness and grace, an unwavering courtesy, self-deprecation, and consideration for other people.” Graceful in his athletic performance, poised at all times, modest in his success, and self-consciously “southern” in his attitudes, Jones symbolized a transitional figure—the traditional regional image of the gentleman in a new 20th-century mass culture context. Through the press and radio in the 1920s, the exploits of “The Emperor Jones” were publicized, and he thereby helped popularize golf with southerners and others who had once dismissed it as an effete game for the wealthy.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Mark Frost, The Grand Slam: Bobby Jones, America, and the Story of Golf (2004); Stephen Lowe, Georgia Historical Quarterly (Winter 1999); Robert Tyre Jones Jr., Golf Is My Game (1959).

Jordan, Michael

(b. 1963) BASKETBALL PLAYER.

It would surprise most basketball fans—who associate Michael Jordan so closely with the Tar Heel State—that he was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. But his family moved to Wilmington, N.C., when he was a child, and it was there that his basketball prowess first became obvious. But he became nationally famous in 1982 when, as a freshman at the University of North Carolina, he hit a 17-foot jump shot to give his team the NCAA championship. Jordan remained in Chapel Hill two years after that, receiving All-American and national player-of-the-year honors, and then, in 1984, joined the professional Chicago Bulls. During his National Basketball Association career, he led his team to six NBA titles and was named NBA player of the year five times. A tremendous competitor, a great shooter, a tenacious defender, and—most famously—a spectacular leaper, he soon became known by the name “Air Jordan.” Often called the greatest basketball player of all time, he was also named by ESPN in 1999 the greatest North American athlete of the 20th century. By the end of his career—partly because of his superiority on the court, partly because of his visibility as a pitchman for numerous products—he may also have become the most recognizable athlete in the world.

FRED HOBSON

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

David Halberstam, Playing for Keeps: Michael Jordan and the World He Made (2000); Michael Jordan, Mark Vancil, and Sandro Miller, I Can’t Accept Not Trying: Michael Jordan on the Pursuit of Excellence (1994); David L. Porter, Michael Jordan: A Biography (2007).

Jubilees