No one knows when people developed boats for transport, but it must have been obvious from observation that large wooden objects floated down rivers with ease: objects that would have been extremely difficult to haul overland. It was only in the eighteenth century that anyone tried to measure the difference between land carriage and water carriage, with experiments that showed that if you put a pack on a horse’s back it could carry up to 1/8th of a tonne and pulling a cart on a well-made road, a rarity at the time, it could manage a maximum of 2 tonnes. But harness it to haul a boat along a river and it could shift a more impressive 30 tonnes and, on the still waters of a canal, the load was increased to 50 tonnes. Tomb engravings show that the ancient Egyptians had boats at least as early as 2500 BC.

Rivers were clearly the most efficient means of moving heavy goods from one place to another and their importance was recognised: in medieval Britain, for example, the Severn was known as ‘The King’s Highway of Severn’. Navigable rivers were invaluable, which is why great inland cities grew up along their banks. But they have problems. The ideal transport route would be a river that flowed smoothly and evenly in a straight line from place to place. Few rivers match that ideal. They meander across the countryside; sometimes they dash furiously through rapids and falls; in other places they widen out with shallows and shoals. And there may be some very bulky commodity that needed to be transported, but which was not found anywhere near a navigable river. A navigable canal avoids these problems, but it requires considerable technical, surveying and engineering skills to construct. In Britain we think of canals as being a product of the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century, but canals were being constructed thousands of years earlier. The story of canals, however, is not one of smooth, continuous development. It is rather more complex than that.

As with the development of boats, the earliest history of canal construction may be lost or obscure, but we do know that the Egyptians began constructing canals during the 6th Dynasty under the Pharaoh Pepi I, who ruled from 2332–2283 BC. Egypt had a major transport problem. The pharaohs wanted to build pyramids, but the sites were seldom conveniently close to stone quarries, so they needed an efficient system for moving massive blocks of stone. An account has survived in the tomb of Weni or Uni the Elder, a general in the Pharaoh’s army, telling us that he was ordered to construct five canals, which were completed in one year, and to build three barges and four towboats of acacia wood. They were to move granite blocks for the pyramid Merenre. The canals were to be used first to bring stone to the Nile and then also to improve navigation on the river. The Nile has a series of cataracts, and at the first of these Weni constructed a bypass canal. This had to be cut through the solid rock and although it was comparatively short, just 90m long, it was wide and deep enough, 10m by 9m, to take the largest vessels on the river.

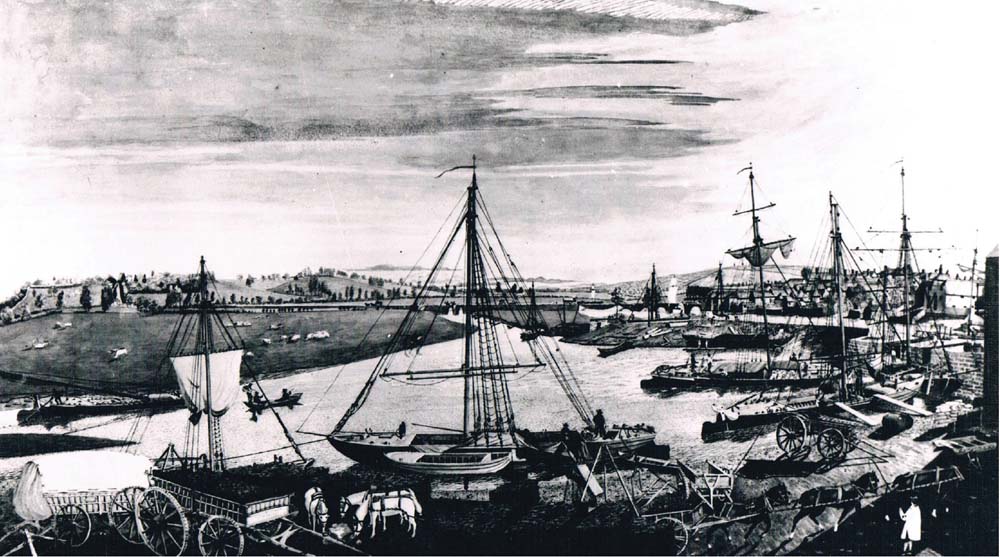

Rivers had been the most efficient means of transporting goods since ancient times, and the prime importance of the Severn in England led to it being referred to as ‘The King’s Highway of Severn’. This busy scene at the confluence of the Severn and the Avon at Tewkesbury in the eighteenth century, with boats of many different types, goes a long way to explain how the name arose. The principal sailing barge of the area was the Severn trow, which in its earlier form was square rigged like the vessels shown here. (Tewkesbury Town Council)

The most ambitious scheme was for a canal to link the Nile with the Red Sea, but information is scant. It was probably built at some time before 1000 BC, but whether it was ever completed at that time is doubtful and it eventually fell into disuse. The scheme was revised when construction began under the Pharaoh Neko or Nekhau. It linked the river to the Bitter Lakes, north of the Red Sea, and was eventually completed under the Persian ruler Darius I. For once, we have a reasonably full account by the Greek historian Herodotus. The quotation comes from Macauley’s translation of Herodotus:

‘ The length of this is a voyage of four days, and in breadth was so dug that two triremes could go side by side driven by oars; and the water is brought in from the Nile. The channel is conducted a little above the city of Bubastis [an ancient city in the Nile Delta approximately 80km north east of Cairo] by Patumos the Arabian city and runs into the Erythraian Sea [Red Sea] and it is dug first along those parts of the plain of Egypt which lie towards Arabia, just above which run the mountains which extend opposite Memphis, where are the stone quarries – along the base of these mountains the channel is conducted from West to East for a great way; and after that it is directed towards a break in the hills and tends from these mountains towards the noon-day and South Wind to the Arabian gulf. Now in the place where the journey is least and shortest from the Northern to the Southern Sea (which is also called Erythraian), that is from Mount Casion, which is the boundary between Egypt and Syria, the distance is exactly a thousand furlongs to the Arabian gulf; but the channel is much longer, since it is more winding; and in the reign of Necos there perished while digging it twelve myriads of the Egyptians. Now Necos ceased in the midst of his digging, because the utterance of an Oracle impeded him, which was to the effect that he was working for the barbarian; and the Egyptians call all men barbarians who do not agree with them in speech.’

Not the most exciting account of canal construction ever written, but it tells us a lot. It is obvious that the route was carefully chosen to maintain a level, suggesting considerable surveying skills. This is not surprising, given that these were the people who managed the complex geometry of pyramid construction. It also indicates that a vast labour force was involved. That is one advantage of being a pharaoh: you can command as many men as you need to do a job. The death toll is extraordinary, even if Herodotus was exaggerating: a myriad is 10,000 so he is telling us that 120,000 died building the canal. When completed the canal was a fine waterway, roughly 50m wide and 100km long. It was opened c.500 BC and monuments were erected lauding the work. Not too surprisingly, Darius claimed all the glory, described as ‘king of kings, king of the countries of all languages, king of the wide and far-off earth’ and the inscription ends ‘This stream was dug as I have ordered.’

We have few details about the working of the canal. We do know that in the third century BC there was considerable reconstruction and a new device was added by Ptolemy Philadelphus, described by a contemporary, Diodorus Siculus, as ‘an ingenious kind of lock. This he opened, whenever he wished to pass through, and quickly closed again, a contrivance whose usage proved to be highly successful.’ That he had to get through as quickly as possible means that it could not have been the sort of lock with which we are familiar, but one with a single gate, holding back water at a higher level that would allow a flood of water to pass through when it was opened. We shall meet this device later when we look at developments in China and at later river improvements in Europe. The canal was not a huge success, largely because of the amount of silt carried down from the Nile, and it fell into disuse. Watery connection between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea was only re-established with the construction of the Suez Canal in the nineteenth century.

During the wars between Persia and Greece in the fifth century BC, Xerxes avoided taking his ships round the long peninsula that ends at Mount Athos and ordered a canal to be cut across the narrow neck of land where it joined the mainland. It was to be 4km long and Herodotus describes how it was dug, the first of its kind in written records:

Few of the earliest canals built in the ancient world have survived in recognisable form, either in physical remains or in pictures. One early scheme planned to cut through the narrow Corinth Isthmus in the south of Greece. The various schemes proved impossible given the available technology. Seeing the canal today, carved deep through solid rock, one can understand why it only finally opened in 1893. (Alfien Crispin)

‘ When the trench reached a certain depth, the labourers at the bottom carried on with the digging and passed the soil up to others above them, who stood on ladders and passed it on to another lot, still higher up, until it reached the men at the top, who carried it away and dumped it. Most of the people engaged in the work made the cutting the same width at the top as it was intended to be at the bottom, with the inevitable result that the sides kept falling in, and so doubled their labour. Indeed they all made this mistake except the Phoenicians, who in this – as in all other practical matters – gave a signal example of their skill. They, in the section allotted to them, took out a trench double the width prescribed for the actual finished canal, and by digging at a slope gradually contracted it as they got further down, until at the bottom their section was the same width as the rest.’

There was an even more obvious site for a useful canal in the Isthmus of Corinth that separates the Peloponnese from the Greek mainland. The first attempt was made in the seventh century BC by Periander, but he soon abandoned the idea of a canal in favour of a portage system overland for his ships. Known as the Diolkos, it consisted of a paved road, with grooves cut to take standard-sized wagons, an idea that re-emerged in Europe some 2,000 years later. There are still traces of this ancient way alongside the modern canal. The canal idea was revised under Demetrius Poliorcetes about 300 BC, but his surveyors told him, incorrectly as it turned out, that there was a difference in sea levels between the two ends, and they feared flooding. He abandoned the idea. The whole scheme was shelved until the Romans revived it. After several false starts, work began under Nero in AD 67. The Emperor cut the first sod himself, then handed over the work to thousands of Jewish slaves, imprisoned during the recent wars. They dug trenches at either end, and in the central ridge they dug exploratory shafts to test the nature of the rock. When Nero died the attempt died with him. Construction of a ship canal only started again in 1881 and if the ancients could have seen the result, they would have realised the impossibility of what they had taken on: in the centre, it carves through solid rock and the almost vertical walls rise to a height of 90m. Such a task would have defeated even the skills of Roman engineers.

In the description of the canal near Mount Athos, Herodotus referred to the skills of the Phoenicians. They were, in fact, masters of canal construction, but their works were built for water supply, not for navigation. Nevertheless, they used advanced technology that could have been adapted for any canal work. One of the most remarkable achievements was a canal to bring water from the Greater Zab to Sennacherib’s capital city Nineveh in 691 BC. It was 50 miles long and paved with stone throughout its course and as wide as a main road. Stone was brought from quarries in the hills and an estimated two million limestone blocks were shifted. One reason for paving the bed of the canal was to use it as a roadway during the construction period. A weir was built across the river to divert water into the canal, overlooked by massive figures of the king himself and various gods, together with an inscription recounting that the whole work was completed in one year and three months.

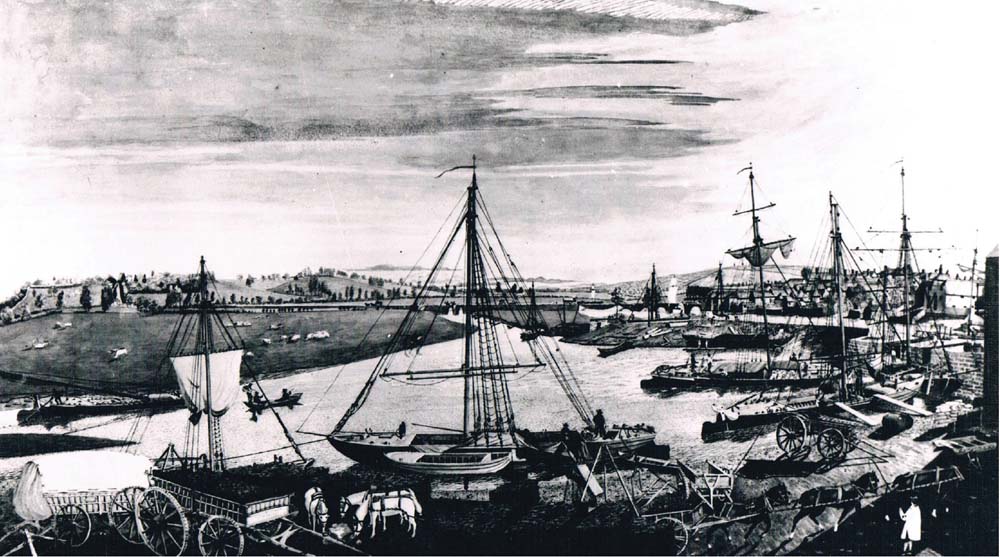

The most impressive single feature was a 300m long stone aqueduct carried on five corbelled arches that crossed the valley near Nineveh. Corbelled arches are constructed by building up a structure of slightly overlapping stones, so that the two sides gradually get close enough together until they can be bridged by a capping stone. It was the Romans who made spectacular use of true arches, in which the arch is built over a wooden former, also known as centring. This is an arch constructed of timber, on top of which the stones can be laid. Once the keystone is in place, holding the stones firmly together, the wooden structure can safely be removed. They used the arches in building even more immense aqueducts for water supply, of which the most famous is the Pont du Gard near Nîmes.

The Romans are famous for their skills as civil engineers, especially for building roads. They were equally competent in constructing canals, primarily for either irrigation or water supply. Some of these waterways were also used for transport. That they could have built imposing canals is obvious from what they did construct, of which the aqueduct over the River Gard, the Pont du Gard, is an outstanding example. It is now classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site. (Wolfgang Staudt)

Most of the 50km of the aqueduct lies underground, but the engineers had, at some point, to cross the River Gardon. They selected a point where the river narrows between rocky ledges that provided solid foundations for the structure. They built six arches, with massive piers each 6m thick and rising to a height of 22m. This created a solid bridge 142m long, on which a row of 11 smaller arches was constructed, extending the length of the aqueduct to 242m. A third layer of even smaller arches, with piers just 3m thick and 7m high, completed the structure that now extended to 275m. Originally there were forty-seven arches in the top layer, but today only thirty-five remain. To build such a structure at all shows great daring and confidence – but it also demanded great accuracy. The water in the aqueduct flowed by gravity along a very gentle slope of just 1 in 3,000; the difference in height between the two ends of the structure is a paltry 2½cm, small but sufficient to keep the water flowing steadily.

The Romans had clearly developed sophisticated surveying techniques – the straightness of their main roads is legendary. Their two principal instruments were the groma and the chorobates. The groma consisted of a vertical rod, some 2m high, with a swivelling crosspiece, with plumb lines suspended from the ends. It lined up the instrument with poles held at a distance by an assistant. The chorobates was rather more complex. It consisted of a rod, as much as 6m long, supported at either end by identical legs. These were joined to the rod by diagonal struts, marked with vertical lines. When plumb lines hung from the rod above, the struts were perfectly in line with the markings, then the rod was level and could be used as a reference point. When the plumb lines would wave about in the wind, the surveyors could use a water trough on top of the rod to obtain a level. However, Jean-Pierre Adam carried out experiments with a chorobates and the best accuracy he could get was 1.16 per cent – nowhere near the accuracy that we find in the actual aqueduct. N.A.F. Smith, in an article in the Transactions of the Newcomen Society (Vol.62), suggests that a different device might have been used, an A-frame level called a libella.

At the Pont du Gard the actual construction was helped by cranes and block and tackle arrangements. The stones were carefully cut and inscribed with a code of letters and numbers, indicating where they would be placed in the structure, marks that are still visible today. One of the more remarkable features of the aqueduct is that no mortar was used: it relied entirely on the accuracy of the mason to provide perfectly shaped blocks that would fit snugly together. There was never any intention of using this system for transport, but as with the Phoenicians the technology could have been used to build navigable canals.

When it came to building canals for land drainage, it is suggested that they would also have been used for boats, possibly even in Roman Britain. One of these drainage systems is the Car Dyke in Lincolnshire, which is certainly post-Iron Age and probably Roman. The section from the River Witham to the River Slea was certainly navigable and there is inconclusive evidence that suggests it was used by boats. No such doubts exist about the Foss Dyke that runs from the Trent, near Torksey, for just over 11 miles to Lincoln and is still navigable today. Bizarrely it ended its working days of cargo carrying in the ownership of the London & North Eastern Railway. What would the Roman engineers have made of that?

Canals of various kinds were constructed over a long period in the ancient world throughout Europe and the Middle East and there were some remarkable achievements. However, nothing built in this period can compare with what was happening across the world in China.

The story begins with a war, when in about 215 BC the Emperor sent troops to conquer the province of Yüeh. According to a document written some time after the event, a fighting force was sent by boat to conquer the region and, at the same time, an order was made for a canal to be cut to supply them with grain during the campaign. It became known as the Ling Chhü or Magic Canal and the engineer was Shi Lu. Early texts refer to the canal but according to Joseph Needham, the author of the most authoritative English language work covering Chinese canal history, Science and Society in China, Vol.4, 1971, the most complete account comes from a work of 1178, which he quotes in a lengthy translation, part of which appears below. The canal was built to link two rivers: the Hsiang that flows north towards the Yangtze and the Li flowing south. Construction involved building up a stone barrier that was known as a ‘spade-like snout’ in the middle of the Hsiang to divide its waters, so that one part could be diverted into the canal. From there the canal entered an embanked section and then followed a contour round the hills for a total of about 20 miles. This section has a natural flow and is provided with numerous spillways to avoid flooding. The most intriguing part of the account describes what it was like to travel the canal:

‘ In the canal there are 36 lock gates. As each vessel enters one of these lock gates, (the people) immediately restore it to its closed position and wait while water accumulates (within the lock) so that by this means the ship gradually progresses.’

In such a way they are able to follow the mountainside and move upwards.

‘ On the descent, it is like water flowing down the stepped groove of a roof, and thus there is communication for the boats between north and south. I myself have seen (I am happy to say) the historic traces of the work of Lu.’

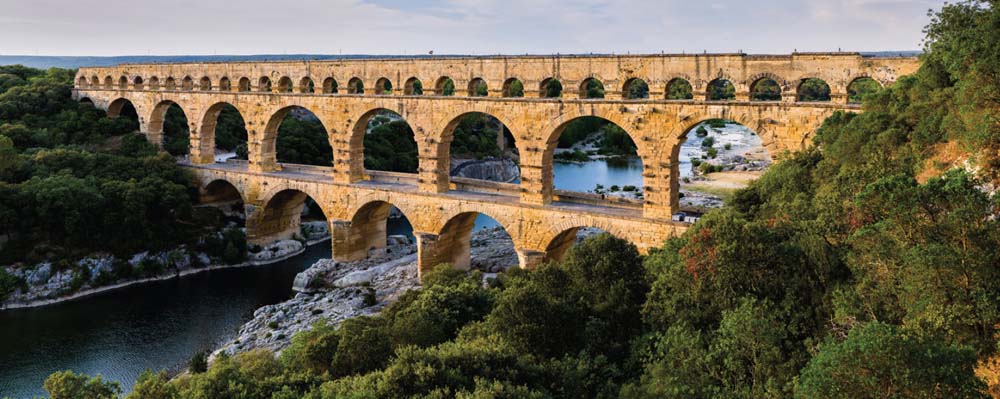

The most complex canal system devised in the ancient world was the Grand Canal of China, the oldest parts of which date back to the sixth century BC. It stretched for more than 1,000km and has survived, although much changed over the years, to the present day. One of the officials with the Macartney Mission to China of 1793 was a draughtsman, William Alexander, who sketched the canal. His drawings appeared as engravings in a book, Costume of China, published in 1805. This illustration shows a lifting bridge across the canal. The team of working men were supplied with the shelter to the right of the bridge.

There can be little doubt that what is being described is some form of pound lock, but it is unknown whether such locks were there from the start of work or were later additions. Where the canal met the Li it continued as a lateral canal beside the river. From all the evidence, Needham concludes that the locks date from the tenth or eleventh century. With its construction, China possessed a continuous line of waterways stretching for more than 1,200 miles and it remains in use.

The best-known ancient canal in China is the Grand Canal. It was not devised as a single waterway but grew out of several schemes spread over many centuries. It had its origins not so much in transport as irrigation. It began with the construction of the Hung Kou, translated as the Wild Geese Canal, which linked the Yellow River with the Huai River. The difference in levels between the two river systems was so small that vessels could use it without needing any sluice or lock. It is usually dated to about the late sixth century BC. The next section was Han Kuo, built as a military canal in the fifth century BC to join the Huai to the Yangtze. In its original form it appears to have been a very meandering waterway that was later modernised. The canal was extended over the centuries and in the sixth century AD new sections were supplied with flash locks: single gates that closed off an upper section of the canal from the lower, but when opened allowed vessels to ride down on the current. Where the differences in levels were too great for a flash lock, slipways were built, along which vessels could be winched up or down. One of the most impressive achievements came when problems occurred in supplying water to the summit level of the canal, 138ft above the mean level of the Yangtze. This was solved in the early fifteenth century, a century after the through route had been completed, with the construction of a vast dam on the Kuang River to create a reservoir. Just as the pharaohs had been able to call up an army of workers for huge construction projects, so the same system could be used in Imperial China. The workforce numbered 165,000 men and they completed the task in just 200 days.

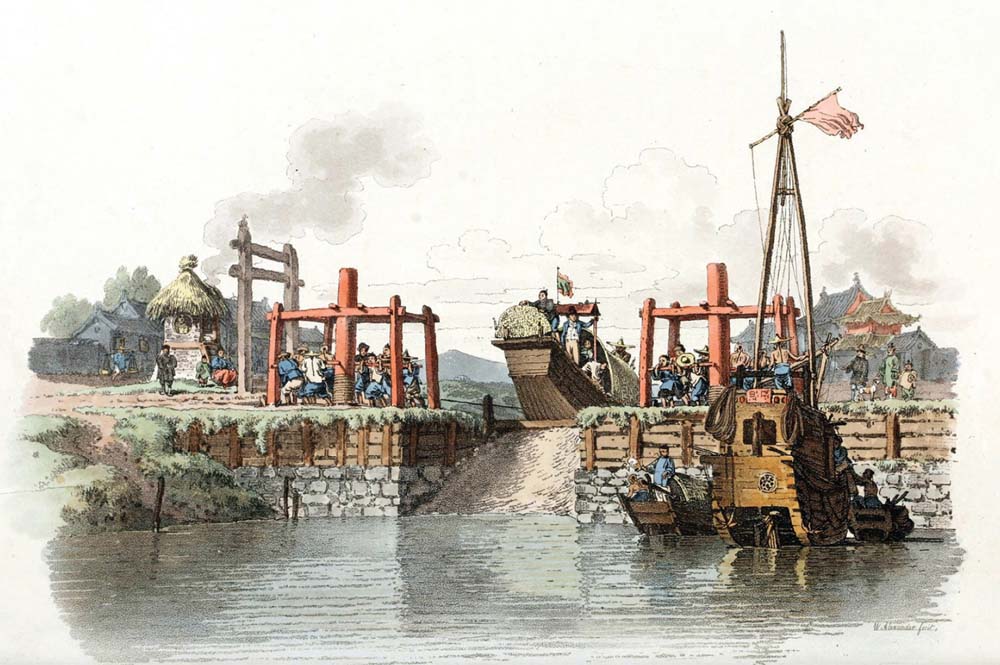

This is another of Alexander’s illustrations of the Grand Canal. Originally the differences in levels between different sections of the canal were negotiated through locks, but in later years these were replaced by slipways. The vessel is being hauled by ropes to the top of the slipway by two gangs of men working capstans. The European standing in the bows is presumably a Mission official.

The Grand Canal was a mixture of river navigations and artificial waterways, and eventually extended for 1,035 miles from Beijing to Hangzhou. It was an immense achievement, but was unknown to Europeans and when they did eventually reach China the pound locks appear to have disappeared, to be replaced by slipways and flash locks. An illustration by William Alexander of the British Embassy shows the canal in c.1800. Where we would expect to see a lock, the boat is about to be lowered on rollers down a slipway. So, in spite of the achievements and engineering ability of the Chinese, the works had virtually no effect on developments in Europe. Everything would have to be invented all over again.