Following the collapse of the Roman Empire and the decline of the great Mediterranean civilisations, Europe entered a period known as the Dark Ages. Rivers continued to be used for transport, but little was done to improve them for many centuries. By the medieval period a new type of obstacle impeded navigation. In Britain, the eleventh-century Domesday Book recorded more than 10,000 mills in England. These were water mills, many of which ensured a steady supply of water to turn their wheels by building weirs. These created a good head of water upstream of the dam, which could then be diverted down an artificial channel to the mill. They also effectively blocked the river as far as transport was concerned.

One of the most detailed accounts of travel on a long river was supplied by John Taylor, waterman and poet. His book The Description of Thames and Isis (1632) sets out to tell the reader, in verse, exactly what he intends to do:

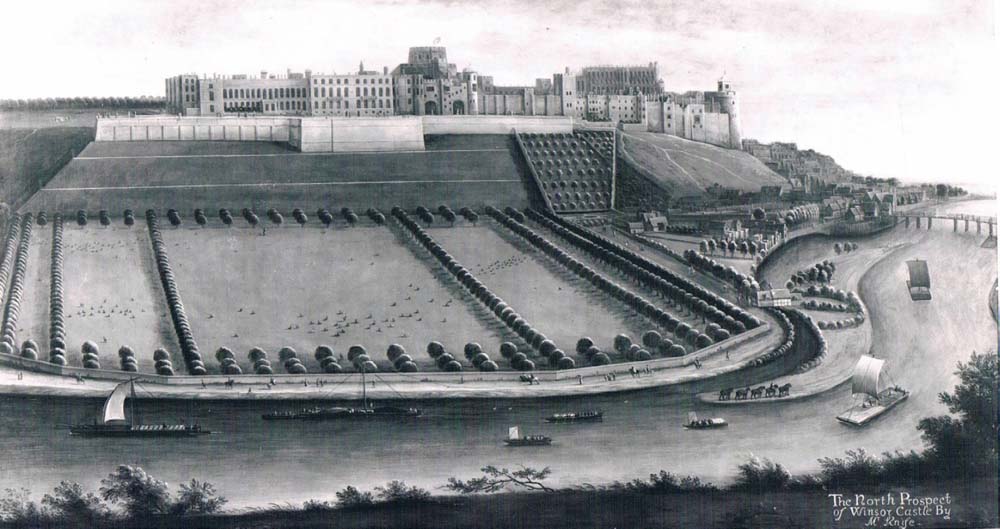

The River Thames at Windsor Castle in the seventeenth century. The early Thames sailing barges have square bows and sterns, not unlike an enlarged version of a modern punt. The ones with sails set clearly have a following wind, whereas barges going in the opposite direction are either being rowed or, having dropped their sails, are being towed. A team of horses can be seen on the spit of land that forms one side of a cutting leading down to the water mill. (Her Majesty the Queen)

‘But I (from Oxford) down to Staines will slide, And tell the rivers wrongs which I espied.’

And foremost among those wrongs were the weirs built by millers:

Haules Weare doth almost cross the river all,

Making the passage straight and very small,

How can that man be counted a good liver

That for his private use will stop a river?’

To overcome such obstacles, the Thames had, by this time, a series of flash locks.The flash lock would be built into a gap in the weir. This consisted of two baulks of timber: one, usually of elm, fixed firmly to the riverbed; the other above the water was moveable. The two beams were joined by vertical posts called rimers, in between which were wooden paddles with long handles. When a boat approached, the paddles were raised, allowing water to flow through so that the gate, with its rimers, could be swung out of the way. This released a flood of water, the flash, which a boat could ride downstream, and boats travelling upstream were winched up against the current. Using the flash locks was by no means straightforward and, as Taylor reported, there were always other problems to contend with:

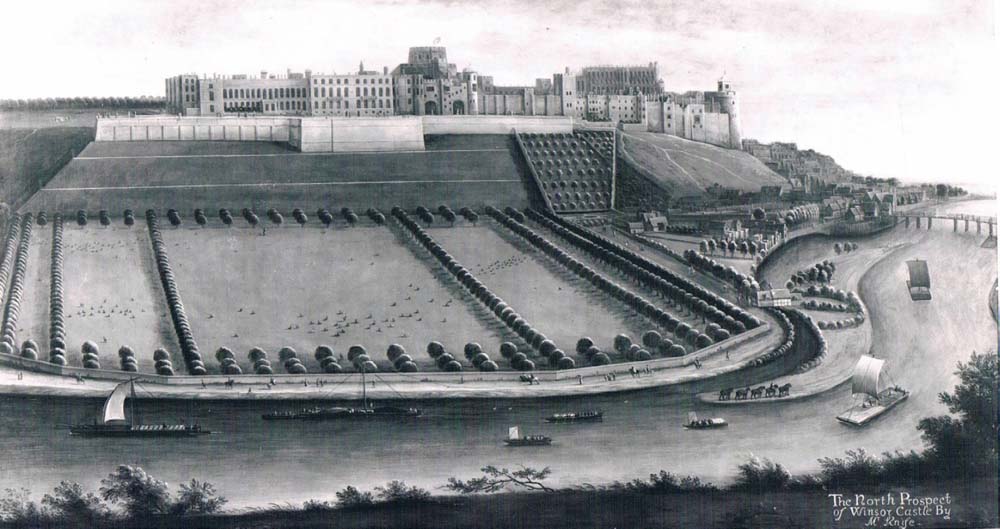

The Monk’s Map of Abingdon is thought to date from the sixteenth century. It shows the town to the north of the bridge. To the right of that, the river divides: the northern branch has a flash lock that allows boats to pass when opened. (Abingdon County Hall Museum)

A typical flash lock from William Armstrong’s nineteenth-century book The Thames. The illustration shows the lock keeper lifting one of the wooden paddles that are set within the vertical timber framework of the ‘rimers’. Once the paddles have been removed, the gate can be swung open to allow a boat to pass down with the rush of water, or ‘flash’ that gives this type of early lock its name. (Anthony Burton)

‘The Sutton locks are great impediments,

The waters fall with such great violence,

Thence downe to Cullam [Culham], streame runs quicke and quicker,

Yet we rub’d twice a ground for want of liquor.’

At least he got down safely. In 1634 a passenger boat, with an estimated sixty men, women and children on board, overturned in the flash at Goring. They all drowned. The earliest reference to such a device on the Thames, known then by its alternative name of ‘stanch’ or ‘staunch’, is 1306. Surprisingly the last flash lock on the Thames was still in use at Eynsham until it was replaced in 1931.

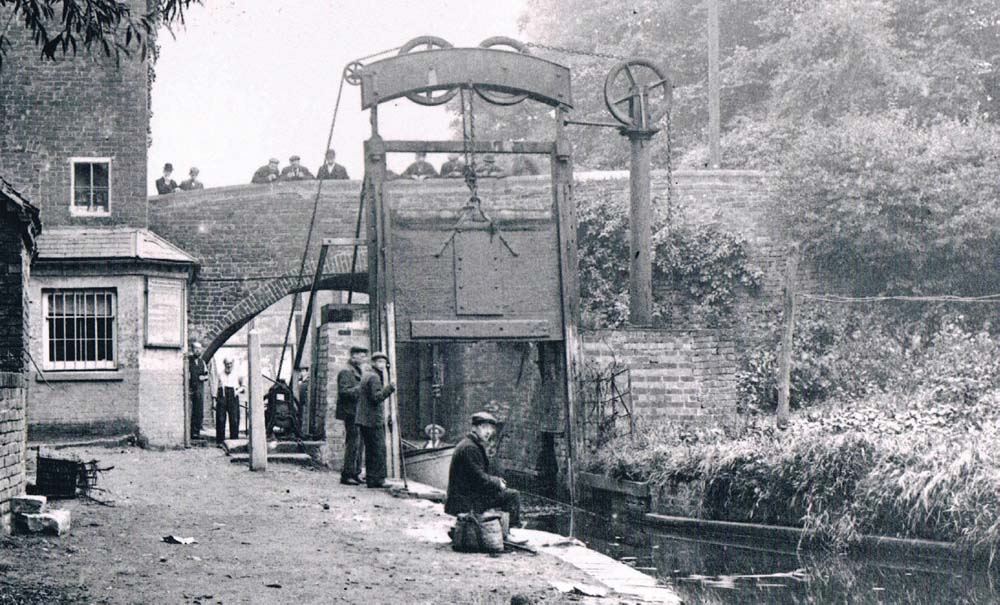

The last flash lock on the Thames remained in place until well into the twentieth century at Eynsham on the river above Oxford. The gate has been opened and the photograph captures the rapid movement of the water. This was a comparatively small drop: with some of the large flash locks the flow would have been even stronger and accidents were common. Vessels moving downstream rode the flood while those going upstream were either manhandled up on small locks or winched up against the flow. (Oxfordshire County Libraries)

As in the ancient world, navigable canals in Holland had their origin in the complex system of dykes used to drain the low-lying lands. The outlets were generally controlled through sluice gates that became obstacles when the dykes were widened to take vessels. There were two options. The earliest solution was probably to unload the cargo and carry it round to load it back into another boat on the far side of the gate. Very early on, however, ramps were built to allow the boats themselves to be hauled between the two levels. The earliest use of ramps appears to date back to the Nieuwe Rijn canal built in 1148. A better solution was to build large sluices so that boats could actually pass through. All these devices were of the portcullis type, in which the gates were lifted vertically instead of being swung open. This system allowed boats to pass between the dykes and tidal rivers and estuaries when the levels were equal. It was at best a clumsy system as tidal waters and dykes only reached a level twice a day. An important variation first appeared at Vreeswilk near Utrecht, where the canal joined the Lek river. Records show that in 1378, two sluice gates were built close together, in effect creating a basin, in which vessels could wait until conditions were right for them to move out in either direction, from river to canal or vice versa. It was, in effect, a very large lock. One lock of this type, built near Bruges at the end of the fourteenth century, had a chamber that measured 30m by 10½m. The idea was not, as we saw in the previous chapter, original. But China had been a closed society and by the time the first Europeans entered the country, the locks on the Grand Canal had been replaced by slipways. It was as if the Europeans had just reinvented the wheel.

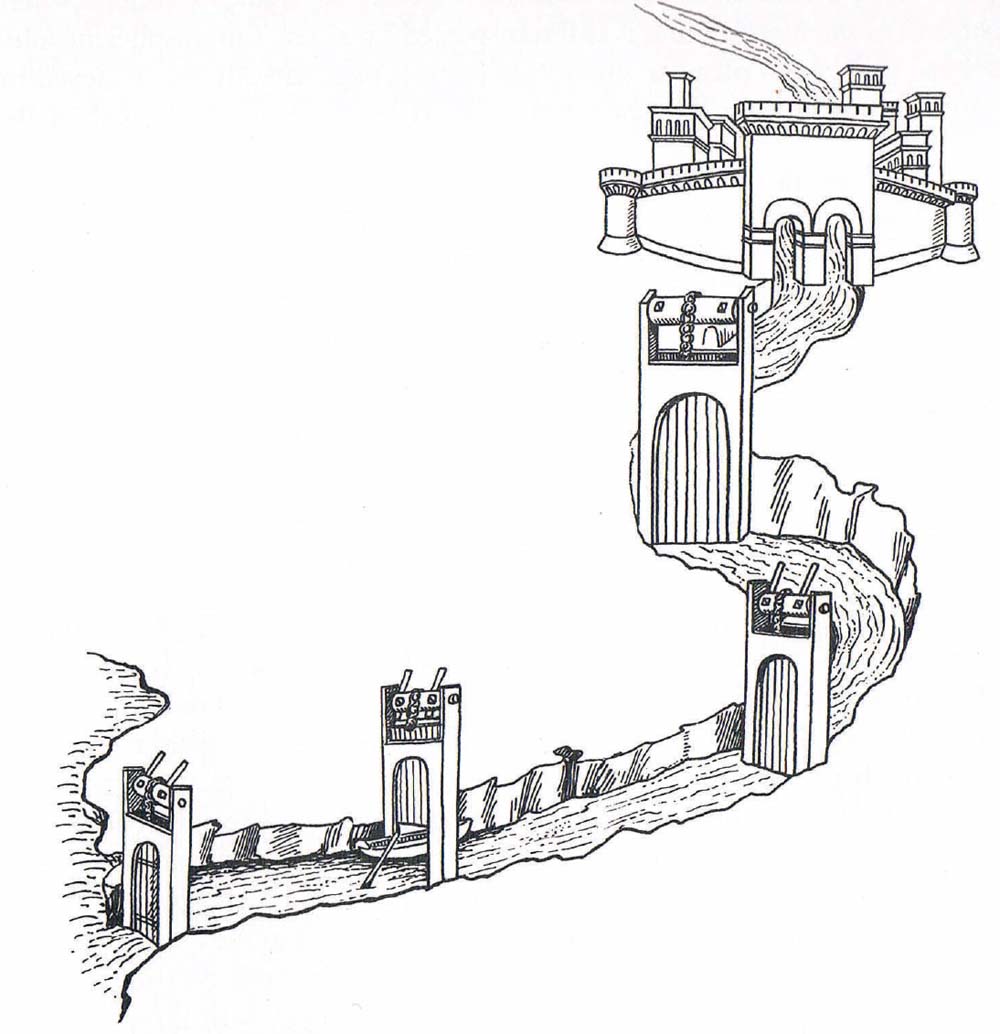

The alternative to the flash lock was the pound lock. As its name implies this is a lock in which the water is impounded between gates. Sluices, controlled by paddles, allow the water to pass in from the upper level of the waterway to fill the lock or to drain out at the lower level to empty it. This early illustration shows the device at its simplest. The two sets of gates are set directly into the river and are raised and lowered vertically, hence the name ‘portcullis lock’. The diagram shows the lifting mechanism set at the top of the portcullis, with no indication of how the lock keeper was actually going to work it. (Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence)

The portcullis, or as it was also known, the guillotine lock, was rarely used on later canals. This example is a stop lock, separating the Stratford Canal from the Worcester & Birmingham at King’s Norton Junction. The sketch in the previous illustration gave only the vaguest idea of how such a lock might be worked. Here it is much clearer. The gate is lifted by means of the windlass that can be seen to the right of the lock and is counterbalanced by weights that can be lowered by means of a chain running over the pulley to the right. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

The Dutch locks were not used to overcome differences in heights in the land – rarely a problem in Holland – but only to make up the difference between the constant levels of the canals and the ever-changing levels of the natural waterways. The next important development was the building of the Stecknitz Canal, between 1391 and 1398. This was a summit-level canal, in other words one that has a central section appreciably higher than the levels at either end. The River Stecknitz had already been made navigable from Lübeck to Lake Mölln, 21 miles to the south by conventional stanches. It was now proposed to continue the southern route as far as the Elbe. The River Delvenau met the Elbe at Lauenburg, but there was still a gap between that river and the lake that had to be filled by an artificial canal. It rose 5m from the lake in less than a kilometre, which involved constructing two locks, 10m long by 3½m beam, each capable of taking ten small boats. Beyond the locks, the canal ran for a further 5 miles in a cutting to reach the river.

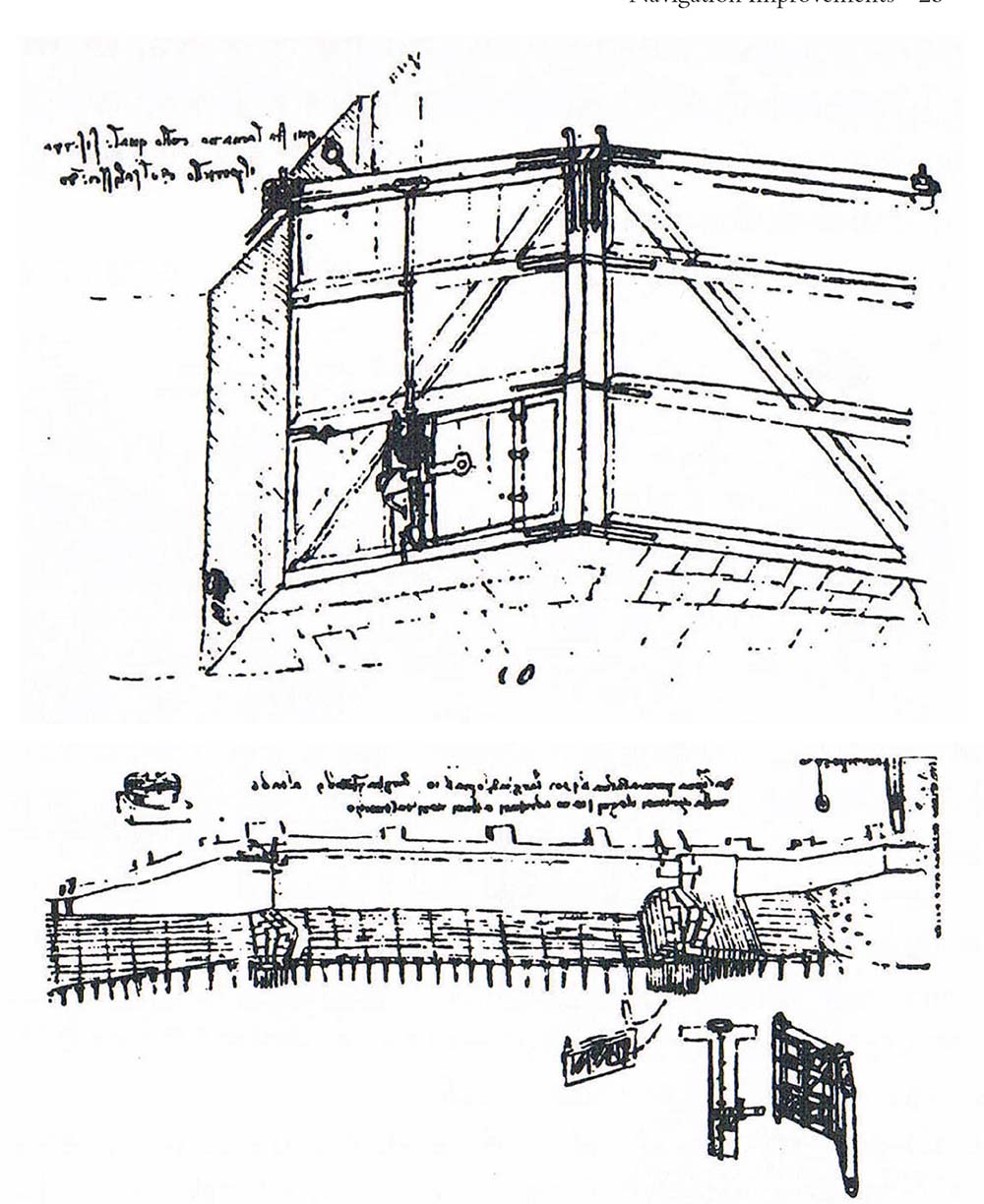

Locks up to this time had virtually all been closed off with portcullis gates, which had to be laboriously raised to a considerable height to allow boats to pass underneath. There is uncertainty about who came up with a new design for lock gates that has remained the pattern for locks ever since, but there is no doubt about who first described and drew them. The Renaissance was a great age for polymaths, and none covered a wider range of subjects and interest than the now world-famous artist Leonardo da Vinci. He had arrived in Milan in 1482 and by 1498 had been appointed as state engineer with special responsibility for overseeing river navigations and canals. He constructed six new locks for the Naviglio Interno in Milan and in 1497 he set about improving the Martesana Canal. Work had begun on this as long ago as 1443 and da Vinci’s task was to design a new lock just below the basin at San Marco. He sketched his idea in a notebook that was later bound with other da Vinci sketches as part of the massive Codex Atlanticus now held in a library at Milan. The drawing shows mitre gates. Instead of being raised vertically they are swung horizontally, meeting at an angle. The gates are both angled to point upstream, so that the force of water actually pushes them closer together to make a good watertight seal. Once water levels are equalised they are easily swung apart by means of balance beams. An almost identical sketch could easily have been made today on almost any canal in Britain.

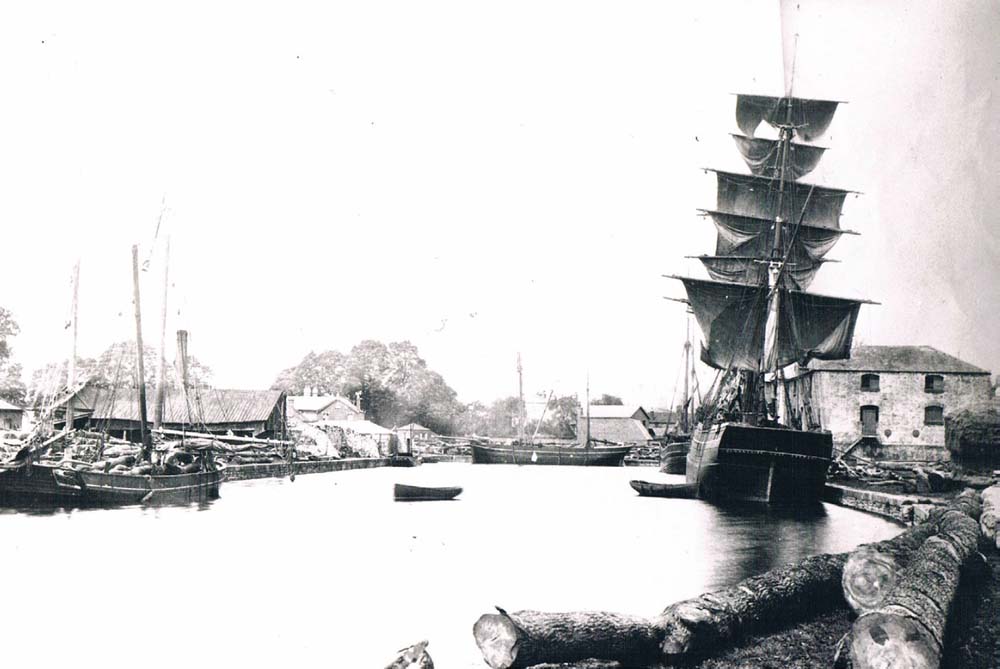

The mitre gates didn’t actually come into use in Britain until the sixteenth century. Navigation on the River Exe between Exeter and the sea was hampered by a structure that effectively closed off the river, the Countess Wear. Control of the Wear was in the hands of the people of Topsham, who had a thriving port and little interest in any changes that would allow ships to bypass them and head straight up to the city. But the citizens of Exeter had other ideas, and in 1564 they employed an engineer, John Trew, to design a canal. Very little is known about him apart from the fact that he was ‘a gentleman from Glamorganshire’. It is a comparatively short canal, a mere 5 miles long, from a basin at Exeter to the point where it joins the estuary. A lock was built at the seaward end, very much in the manner of the Dutch holding locks. It was an immense affair, 189ft long and 23ft wide, closed at the upstream end with a pair of mitre gates. These had six sluices covered with paddles built into them to let the water in and out. The estuary end was closed by a single gate. The sides of the lock were lined with turf and although the original has long since been replaced, it is still known as Turf Lock and is overlooked by The Turf pub. The canal allowed large ships to reach the heart of Exeter and is officially known as the Exeter Ship Canal, but its importance dwindled as ships increased in size, soon reaching a point where larger vessels could no longer fit into the canal.

The portcullis was difficult to operate and created problems for high-masted vessels using the waterway. A better solution would obviously be conventional gates, but there would have been a tendency for them to be forced open by the pressure of water behind them. The solution was found by Leonardo da Vinci with his invention of the mitre gates. As the sketches show, the gates meet at an angle, with the ‘vee’ always pointing towards the higher level of water. As a result, instead of tending to push the gates apart, water pressure held them closer together. This is the system, invented in the fifteenth century, which is found in all modern canals. (Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan)

Work on improving navigation on the German rivers, Havel and Spree, took place in the sixteenth century. One of the first locks built was constructed at Brandenburg in 1548 and the work was completed in 1578 with the opening of a lock in Berlin. This sketch of the Brandenburg lock was reproduced in a German technical journal of 1908. Unlike modern locks, this was in effect a holding basin, designed on an octagonal plan with narrow openings at either end. The form of the lock gates is unknown. The diagram clearly shows the sides of the lock as being built up of timber piles.

Many of the sixteenth-century canal locks built in Europe shared the Turf Lock’s overall structure, being in effect holding basins that could take several vessels at any one time. One good example is the octagonal lock at Brandenburg, built between 1548 and 1550. In Britain, the first lock constructed with mitre gates at both ends was built as part of a scheme for improving navigation on the River Lea at Waltham Abbey. There is a poetic account of the structure, published in 1590: A Tale of Two Swannes by William Vallan. This fanciful work finds two swans travelling up the river to see all the sights. It is worth quoting at some length, both as one of the earliest descriptions of an English river navigation, and also because it shows that this was still such a novelty that Vallan thought it worth explaining in some detail to his readers:

A similarly large lock was built on the Exeter Canal at much the same time as the Brandenburg lock. The route along the River Exe to the sea was blocked by the massive Countess Wear, so a canal was built to bypass it. Intended to take the largest ships of the day, it brought vessels right up to the edge of the city, where a large basin was constructed, together with a new customs house. This early photograph is excellent evidence that large sailing vessels could reach the dockside in Exeter. (ISCA Collection)

‘Down all along through Waltham street they passe

And wonder at the ruines of the Abbey,

Late supprest, the walles, the walkes, the monuments,

And everie thing that there is to be seene.

Among them all a rare devise they see,

But newly made, a waterworke: the locke

Through which the boats of Ware doe passé with malt.

This locke contains two double doores of wood,

Within the same a Cesterne all of Plancke,

Which onely fils when boates come there to passe

By opening anie of these mightie doores with sleight

And strange devise…’

A lock, with a wooden chamber and double mitre gates, was clearly a great curiosity.

Canals spread across much of Europe in the sixteenth century. In what was then Flanders, now Belgium, a canal was built to join Brussels to Willebroek on the tidal River Rupel. The aim was to greatly shorten the distance that coastal vessels had to travel to reach Brussels. It was first approved by Philip the Good in 1483, but the city of Mechelen that was doing rather well out of taxation on vessels using the original river route, objected. The plans were shelved until 1550, when work began and the Mayor of Brussels, Jean de Locquenghien, cut the first sod. He also acted as director of the project with an assistant to help with the surveying and two resident engineers to supervise the day-to-day construction work. It was a canal built to a generous scale: 28km long, 30m wide and 2m deep, with locks constructed to take a dozen small coastal vessels. There were initially just four locks to overcome a fall of 10½m. One problem was the need to cross seven substantial streams along the way: all were diverted under the canal in wooden culverts, one of which leaked so badly it had to be replaced by a new one constructed of masonry. The most imposing engineering works was a cutting 3km long and up to 10m deep.

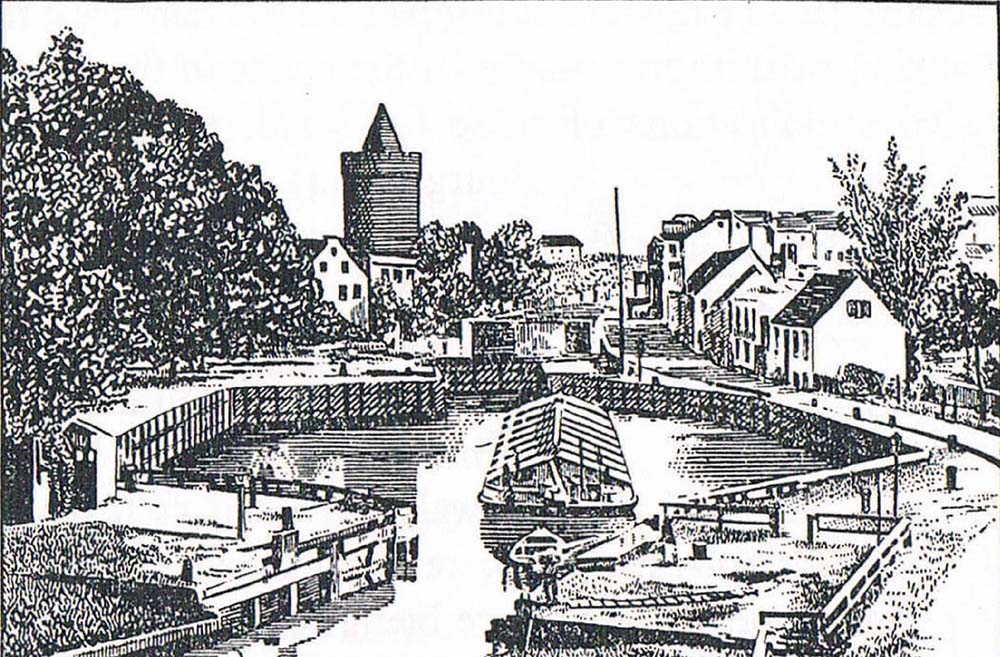

Among the most important early river navigations was the Aire & Calder. This view of the navigation at Leeds by J. Le Keux is dated 1715. It shows the sort of arrangements that were made. The sailing barge is approaching the lock that is set in a long artificial cutting. To the right of the cutting is the weir that allows water to flow freely, even when the lock is in use, unlike the primitive portcullis lock shown earlier. (Leeds Central Library)

The final section of the canal between the lowest of the locks and the river ran between two dykes, separating it from the low-lying marshy land to either side. Being linked directly to the river, this section of the canal was tidal. Soon after the canal opened in 1561 this reach caused trouble as silt was carried up from the river. In 1570 a tidal lock was built to cure the problem. This was a massive affair with three pairs of gates: one pair at the river end and two at the canal end. The inner pair were mounted above a low sill, the outer pair only reaching down to the level of the canal bed. It was a great success for almost everyone. Brussels became a busy inland port with several new canal basins. The losers were the citizens of Mechelen who, as feared, saw their tax revenue die away.

In Britain in the seventeenth and early eighteenth century, the emphasis was not so much on artificial canals as on improving existing river systems. In 1660 there were roughly 660 miles of navigable river in Britain. By 1720 that figure rose to 1,160 miles. Among the more ambitious schemes was that for the Aire & Calder Navigation. The Aire has a dramatic start in life at the foot of the limestone cliff of Malham Cove and then vanishes underground for a time before emerging in full flow in Airedale. This area was already noted for its thriving woollen industry, at this time still largely carried out in workers’ own homes. The Calder rises high in the Pennines above the town of Todmorden and, like the Aire, runs through an area noted for its woollen industry. The two rivers unite at Castleford and beyond that the waters are navigable all the way to the Humber estuary.

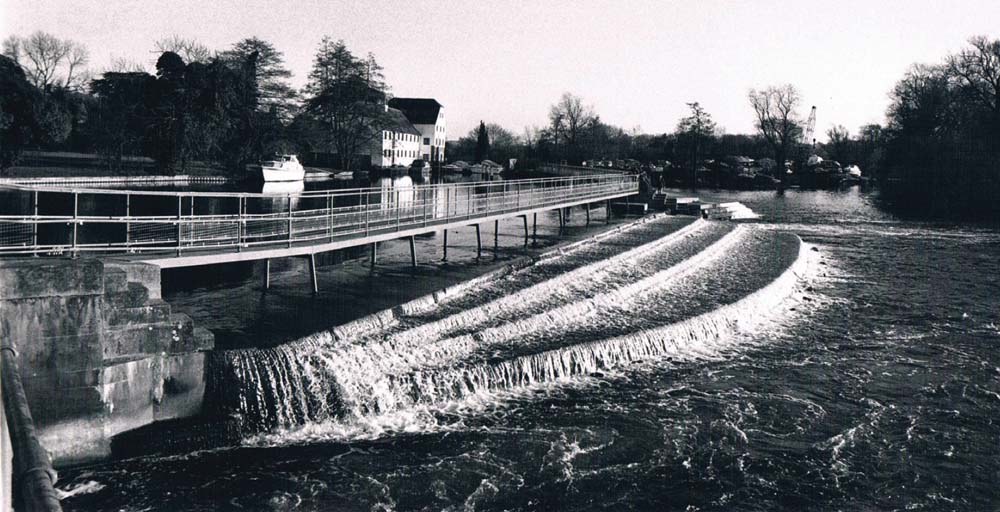

The weir was as important a feature of the river navigation as the lock and represented just as great a challenge to the engineers. This fine, curving weir and footbridge are on the Thames at Hambledon. Like many navigation weirs the site was chosen because there was already a water mill on the site. The present mill can be seen in the background, but is comparatively modern: there is mention of a mill on the site in the Domesday Book. (Anthony Burton)

The lock gate had scarcely changed in design or in the way it was manufactured since Leonardo’s time. These gates are being built in the Grand Union Canal maintenance depot at Bulbourne in the early twentieth century. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

It was the clothiers of such important textile towns as Leeds, Halifax, Rochdale and Wakefield who clamoured for improvements to the navigation. An Act authorising the work was proposed as early as 1625, but the Bill was rejected; the idea was revived in 1697. An initial survey was carried out by John Hadley, described as ‘a great Master of Hydraulicks’, accompanied by Ralph Thoresby, a merchant best known for his work as an antiquarian, and the Mayor of Leeds. Thoresby’s diary of the expedition noted that ‘the ingenious Mr. Hadley questions not its being done, and with less charge than expected, affirming it the noblest river he ever saw not already navigable’. In January 1698, Lord Fairfax introduced a Bill into the Commons to make the Aire navigable from Leeds and the Calder from Wakefield. All the major manufacturing centres supported the Bill, arguing that the navigation was essential for their trade, and quoting the terrible condition of the roads in evidence. The Leeds petition, for example, pointed out that goods had to be taken 22 miles to Rawcliffe, then the nearest point on the navigable section of the Aire, ‘the expense whereof is not only very chargeable, but they are forced to stay two months sometimes while the roads are passable to market, and many times they receive considerable damage, through the badness of the roads by overturning.’

The Act was passed in May 1699 and Hadley was appointed Chief Engineer at an annual salary of 400 guineas, roughly £45,000 at today’s prices. To overcome a rise of 68ft in 30 miles to Leeds, ten locks were built, and the rise of 28ft in the 12 miles to Wakefield required four locks. The arrangement was typical of river navigations of the time. This involved building a weir across the river and bypassing this with a short artificial cutting containing the lock. No one considered a joined-up system, so individual waterways had locks built to an appropriate size for the barges already in use in that area. In the case of the Aire & Calder Navigation this meant locks 58ft long by 15ft wide that could take the sailing barges of the Humber – the Humber keels.

There were many similar schemes throughout Britain and Ireland, but individual engineers had their own ideas. Some rivers presented far greater problems than those found on the Aire & Calder. One of the most problematic was the Kennet Navigation, from Newbury to the Thames at Reading. The natural river fell 138ft in less than 20 miles. The first engineer employed when work got under way following the passing of the Act of 1715 took the easiest way out. Mill weirs were already in place on the river and he simply put locks next to those and left the river to make its own way to the Thames. This proved totally unsatisfactory and one of the principal owners of the canal, a Newbury maltster, arranged for his son John Hore to take over the works. Hore took a very different approach. There were now eighteen wide locks, all set in artificial cuttings that were so extensive that they represented 11½ miles of the total 18½ miles of the whole navigation. It was now more canal than it was river. The locks had to take the typical large barges in use on the Thames, and Hore used the same technique as on the Exeter Canal, building turf-sided locks. Two of these still survive, with the upper part of the lock being sloping, grassy banks.

Theoretically, the new navigation offered a far wider trade route along both the Kennet and the Thames. The engineering problems had been solved, but the planners had not taken account of the rivalry between the different traders. When William Darvall, a barge owner from Maidenhead, tried to bring his vessels all the way to Newbury, he received bloodthirsty threats in a letter simply signed ‘wee Bargemen’. Dated 10 July 1725, it began: ‘Mr Darvall wee Bargemen of Redding thought to Acquaint you before ‘tis too late, Dam You, if y. work a bote any more to Newbury wee will Kill You if ever you come any more this way. Wee was very near shooting you last time, wee went with to pistols and was not too Minnets too Late.’ Perhaps assuming Darvall might think a murder threat was implausible, they continued by saying that if they found the boat at Newbury, they would bore holes in it and sink it. It is hard to believe this now placid waterway was once the scene of such violence. There are no records of whether Darvall heeded the warnings, but neither are there any reports of murders and sinkings.

With the Kennet Navigation, we have a waterway that is more artificial than natural, but it was almost half a century before Britain acquired a canal that was built entirely independently from any natural river or stream. That was certainly not the case in continental Europe. It was here that a new age of canals would be born.