Many of the great cities of the world developed either as seaports or on navigable rivers. Some improved on the natural waterways by building canal networks that became so extensive as to serve as defining features of those cities. Most people will put Venice at the top of the list, but it is very much an exception. There is very little evidence of the earliest settlements, but there is general agreement that before the days of the Roman Empire the large expanse of marshy land of the Venetian Lagoon was occupied by fishing communities, living in houses built on stilts. With the attacks on cities of the Roman Empire by forces from northern Europe, many fled to the Lagoon as a place of safety, and the modern city grew. The new citizens looked for rather more substantial houses, and built them on wooden piles to raise them above water level. They created a myriad of small islands, and the inlets and channels became the main means of getting around. As time went on, these natural waterways became too shallow and narrow to take the increasing traffic, so many were dredged and their sides reinforced with stone. One of these natural waterways was a river that carved a great S-shape through Venice, and this became the Grand Canal. In other words, the canals of Venice are not canals in the sense of being entirely man-made, but rather more akin to river navigations. Other cities created entirely artificial systems.

Amsterdam, like so many places in the Netherlands, was developed on reclaimed land on the banks of the Amstel River, where it joined the IJ, an arm of the Zuider Zee. The marshy ground was drained with a system of dykes and dams or levees – the main earthwork surrounding the area was the Amstel Dam, which gave the developing town its name, and Dam Square is still the heart of the modern city. As elsewhere, the dykes were used for transport as well as drainage. The settlement developed as an important port and at the end of the fifteenth century the Singel Canal was built from the waterfront on the IJ Bay to the Amstel River, to enclose the city. It was mainly intended as a defensive moat and at first it was forbidden to build outside the canal. However, by the end of the sixteenth century, Amsterdam was prospering as an international port and major shipbuilding centre. Its importance grew following the establishment of the East India Company in 1602, which brought a lucrative trade in spices to Europe. It was followed in 1621 by the West Indies Company, which also had a prosperous but less innocent trade – slaves from Africa. The city could no longer be contained within the Singel, so the city fathers, rather than allow uncontrolled growth, planned an extensive new city based on concentric canals.

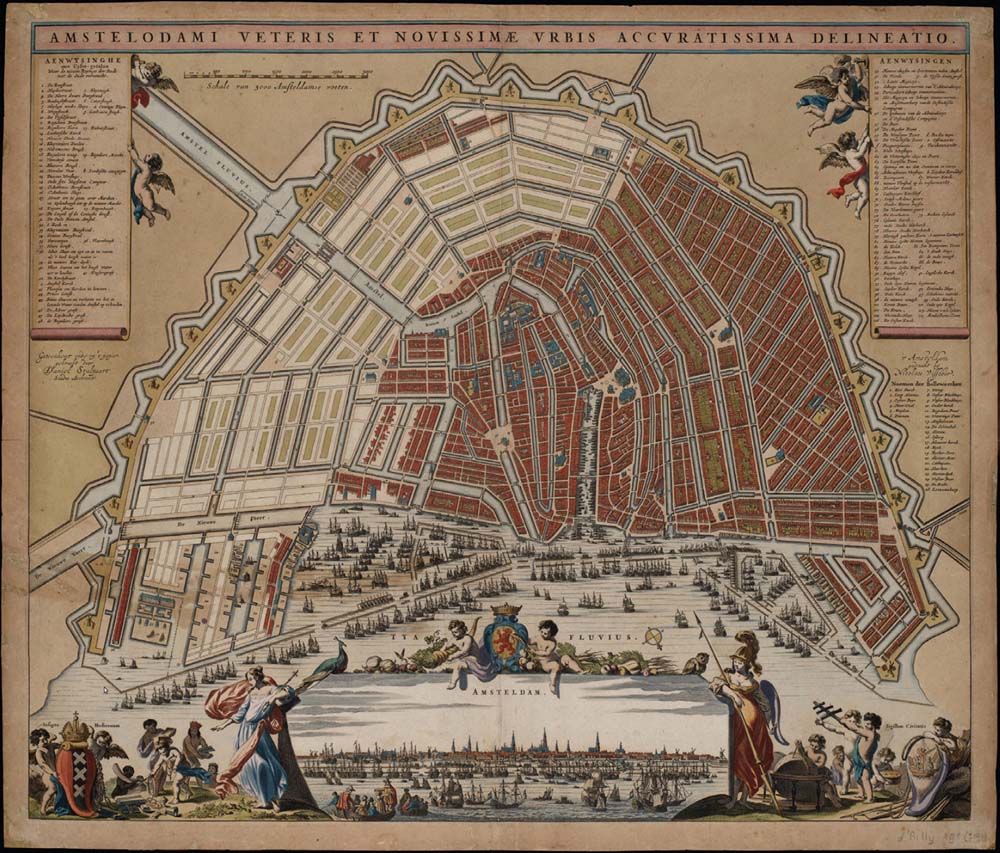

Work began with the building of a new outer defensive canal, the Singelgracht, designed by Daniel Stalpaert. Once completed, it left a large area between that and the older Singel for development. Instead of being left to the sort of higgledy-piggledy patterns of streets and houses that characterised many developing towns in the medieval period, it was carefully planned. The project, designed by Hendrick Jacobszoon Staets, involved draining the land and building three more concentric canals to attach the new city area to the new port that was growing inside the Singel. The land between the canals would be drained and building plots sold along the new waterways. All three canals were dug simultaneously, starting at the southern end. The driving force behind the enterprise was the wealthy merchant class, who supervised the work and drew up building regulations in what was an important early example of urban planning, which was widely followed.

A 1662 map of the canal system for Amsterdam designed by Daniel Stalpeart, in which a series of concentric canals defined new areas for development for the city and set an outside defensive boundary. The map also shows how the canals followed roughly along the lines of old fields and their surrounding dykes. The busy scene depicted at the foot of the map also demonstrates how the enlargement gave Amsterdam the much broader waterfront that was essential for its increased trade. (Rijk Museum, Amsterdam)

The innermost canal is the Herengracht, roughly translated as the Lords’ Canal. Here the land prices were highest but most sought after. It was considered so prestigious to own property here that the wealthiest citizens bought double plots on which they built some of Amsterdam’s grandest houses, many of which still stand. This very fashionable area exuded wealth and became known as the Golden Bend. The Keizersgracht – Emperor’s Canal – is next in the series, and the third is the Prinsengracht, the Prince’s Canal, which is the widest. The system was completed by radial canals, one of which was the Brouewrsgracht, named much as it sounds after the breweries built on its banks. This was also an area of large warehouses and ships’ stores, and was home to many officials of the East India Company. The canals gave Amsterdam its unique atmosphere, in which there was little distinction between commercial and domestic buildings. The Verversgracht, later Zwanenburgwal, was originally named after the dyers and the thriving textile industry along its banks – but it was also to be the home of arguably the country’s greatest artist, Rembrandt. UNESCO has designated the Amsterdam Canal District a World Heritage Site, citing that ‘Amsterdam was seen as the realisation of the ideal city that was used as a reference urban model for new cities around the world.’

This painting of 1672 by the Dutch artist Gerrit Berckheyde shows the Herengracht, or Lord’s Canal, in Amsterdam. This part of the canal became known as The Golden Bend because it attracted the wealthiest citizens to buy land and build along its banks. The opulence and grandeur of the houses is clear from the picture, and many of the buildings still survive: The Golden Bend is still golden. (Rijk Museum, Amsterdam)

On the other side of the world, a city was to be developed that had characteristics of both Amsterdam and Venice. In 1782, King Rama I of Thailand decided to establish a new capital along the eastern bank of the Chao Phraya River. He named it Krung Thep Maha Nakhon, which proved too much for Europeans and they renamed it Bangkok, although it remains Krung Thep to the Thai. The original settlement near the river mouth was defined by a canal that acted as a moat, together with a defensive wall. Within the wall, the area was dominated by temples and the homes of the Chinese community; the area outside was a mixture of residential areas and farmland. As in Amsterdam, an imposing new canal, some 20m wide, was added outside the original one, also acting as a defensive moat, leaving an area in between the two for development. The names of the two canals can be translated as the Former City Moat Canal and the City Moat Canal. The two canals were joined by radial canals, known as Lots. There was one other major canal, the Mahanak, which ran out from the City Moat Canal into the countryside. It had an important role in bringing produce into the new city.

Like Amsterdam, Bangkok was planned around a system of canals, which were constructed in the eighteenth century. They are called klons, and even in the twentieth century they remained vital to the life of the city. The photograph, taken in 1961, shows two important aspects of life on the klons. Houses were built right alongside the waterways, which were the main transport routes, for the city had very few roads, and the klons were vital for bringing supplies in from the countryside. Many of the boats in the picture are full of produce for sale in one of the many floating markets. (SAS Scandinavian Airlines)

The whole scheme was completed in 1785 and the canals defined the different parts of the city. The area inside the Former City Moat Canal was the centre of government, with the Grand Palace at its heart and important government buildings. Between that canal and the outer ring, the Lots divided the area into three sectors: one for high court officials, another for the lower government ranks and a third for foreigners. Development spread outside the City Moat Canal more haphazardly.

Although the canal system was devised partly as a defensive and town planning system, it was also as a means of controlling water levels, as Bangkok sits on a flood plain. They were to provide the main transport system for the city. Houses crowded along their banks, and a large part of the population lived in floating homes. Produce was brought in and sold in floating markets. They also, like the Venetian Canals, were the thoroughfares of the city. Everything moved by water. There were no roads in Bangkok during the first century after its creation, only raised walkways and all the bridges across the canal complex had to be lifted whenever boats passed. As the waterways were permanently busy, this must have been a huge inconvenience, and made travel by boat all the more attractive. The canals are still in use, but no longer dominate the city; but Bangkok can certainly claim to be one of the great canal cities of the world.

Bangkok has been called, not unreasonably, the Venice of the East: the title Venice of the North is usually given to St. Petersburg. The city was born out of conflict, the war between Sweden and Russia at the beginning of the eighteenth century. The Russian forces under the Tsar Peter the Great took the Swedish fortress of Nyenschantz at the mouth of the Neva. It was in too bad a condition to be repaired so a new fortress was constructed on the island of Zayachy Ostrov (‘Hare Island’). Completed in 1703 it was named the Fortress of Peter and Paul and it was the start of what would become the city of St. Petersburg. The Tsar chose the site for his new capital not only for its strategic position, but also because it opened up routes with Western Europe. Peter had travelled widely and was determined to bring Russia into the modern world: in particular he had studied the shipyards of Europe and saw his new capital as the centre around which a Russian industry could develop. But before his grand plans could be realised, he had to drain the marshy land on which he could build.

The work would involve a vast army, mainly made up of serfs. Accommodation was poor and the climate can be fierce, especially in winter when temperatures can drop to-10°C or even lower. The workers suffered from lack of food, terrible housing and long hours. No one kept records of the casualties, but it has been estimated that thousands died in creating the city. They dug canals, cleared land and straightened and embanked rivers. They transformed an entire landscape.

Peter the Great’s original plans envisaged a city in which the majority of traffic would move along the rivers and canals, which became the main arteries for building. The first settlements spread out along the Neva, which was straightened and its banks reinforced with wooden piles. A network of canals and canalised rivers was developed that defined the new city and its limits. The Moyka River was the first to be enclosed between granite banks, a system that soon spread to the other rivers and canals, including the Neva, and became one of the characteristic features of the city’s waterways. The outer limit was fixed by the Fontanka River. That was not its original name: Fontanka is a fountain and the name was given in the 1730s, when aqueducts from the river were built to take water to feed the city’s fountains. Beyond the river was a tract of wild forest, home to roving bands of brigands, which was why police stations were built all around the periphery to protect travellers.

The canals of St. Petersburg were mainly built in the early eighteenth century during the reign of Peter the Great. Today they have become as popular with tourists as those of Amsterdam. This boatload of sightseers on the Griboedov Canal is passing the ornate Church of Our Saviour of the Spilled Blood, a name that refers to the assassination of Tsar Alexander II near this spot. (St. Petersburg Tourist Board)

A canal was built between the Fontanka and Moyka, more or less parallel to them. The Griboedov is narrow and twisting, but famous for the picturesque buildings along its banks. The best known is the Church of Our Saviour of the Spilled Blood, which got its exotic name because it stands close to the spot where Alexander II was assassinated by anarchist bombs. The canals were not just built for commerce; they were intended to be part of the beautification of the city. The short Swan Canal, for example, joins two attractive open spaces: the Summer Garden and the Field of Mars.

The St. Petersburg canals have always been noted for their very attractive features, as exemplified by the beautiful wrought ironwork on these railings on the Denidov Bridge. (Alexei Karprianov)

A distinguishing feature of the St. Petersburg and the other city canal systems already described is that the waterways were seen as essential features that were to be as attractive as they were useful. The nearest thing to a canal city in Britain is Birmingham, which often boasts of having more miles of canal than Venice. But here the situation was very different. The Birmingham canal system was always seen as useful rather than attractive, something to be hidden away behind back streets. Older readers may remember when Gas Street Basin, for example, was a secret enclave, hardly detectable unless you arrived by boat. Access from the road was down steps that curled round a high brick wall that shut off the view. The only clue that there might be anything interesting behind the wall was a red wooden hatch – an indication that firemen could open it up and push their hoses through to suck up water. Rather than seeing the canals as assets, they were largely regarded as handy places to deposit supermarket trollies and dead dogs. They may have played a vital role in developing the city’s industries, but they were not seen as attractions.

The old world of the Birmingham canal system was typified by Gas Street Basin, once tucked away unseen behind high brick walls and warehouses. It still retains much of its old atmosphere, enhanced by traditional narrow boats and some of the old surviving buildings beside the lock. The lock itself is very shallow and was constructed to form a barrier between the Worcester & Birmingham Canal and the Birmingham Canal. (Anthony Burton)

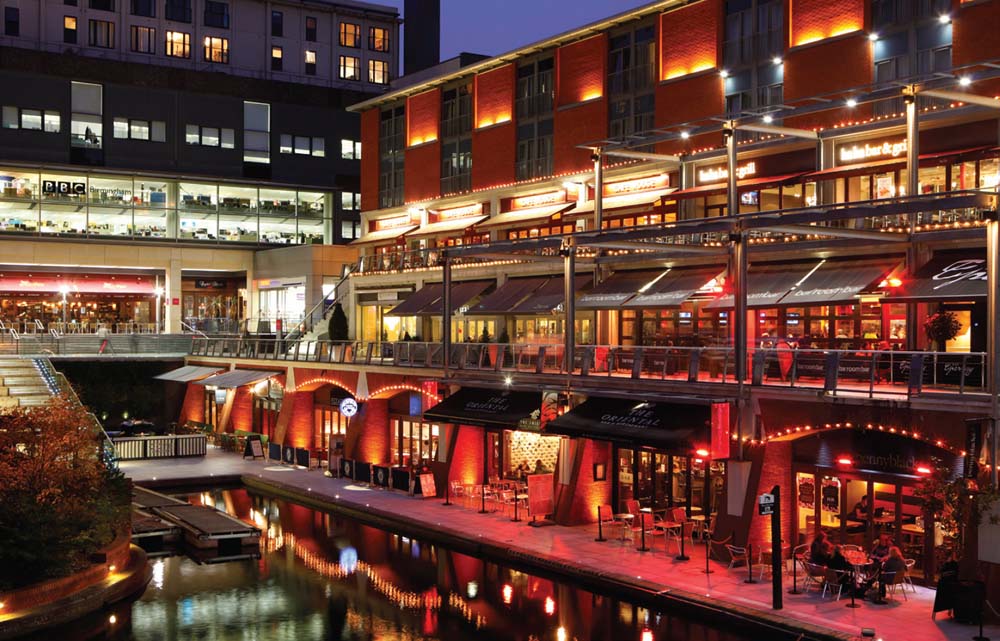

New developments have transformed the Birmingham canals. The Mailbox development, named after the old Post Office sorting centre that once stood on the site, stands close to Gas Street Basin beside the Worcester & Birmingham Canal. This section of the canal is now lined with popular bars and restaurants. (Visit Birmingham)

Change began in the late twentieth century with the development of the area at the top of the Farmer’s Bridge flight, where old buildings were restored and a new canalside pub built. But it is only in the last few years that everything has been transformed. Those of us who have been travelling the Birmingham canals for many years scarcely recognise the system today. New buildings of glass and steel stand at the water’s edge and the banks in the city centre now bustle with life, lined with bars and cafés. Perhaps now, two and a half centuries after it got its first canal, Birmingham can truly be added to the list of genuine canal cities.