The idea of ship canals was not new in the late eighteenth century: the Exeter Ship Canal and the Canal du Midi are early examples. The idea had, however, not been developed again for some time. Telford had a hand in three such canals: two in Britain and one in Sweden. They were canals on a large scale and introduced mechanisation into the construction process.

The first of the trio began life as the Gloucester & Berkeley Canal with an Act of 1793. It was intended to bypass shoals and shallows on the River Severn to allow the largest vessels of the day, up to 15ft draft (later extended to 18ft), to carry on from Berkeley Pill to Gloucester. In spite of the dimensions of the canal, it should have been straightforward, running through largely flat country, with the only locks being those needed to join the canal to the river at either end. The chief engineer was Robert Mylne who, like many in his position, spent little time on the site, entrusting the work to juniors and experienced contractors. But it all went wrong from the start. The man on the spot was Dennis Edson, whose track record was less than inspiring: worked on two canals, dismissed from two canals. For a canal of these dimensions, a huge amount of earth would need to be excavated, so a major contractor should have been involved: the man who got the job had to borrow planks from the parent company. Edson lasted just nine months and was replaced by 26-year-old James Dadford.

A newly developed excavating machine was brought in to speed things up. It was powered by steam and worked something like the now familiar bucket dredger in which a continuous chain of buckets scooped up the earth. It could remove 1,400 barrow loads of spoil in a twelve-hour working day. We know little more about the machine, but all the evidence suggests it was not a success. By 1799, the canal, which had been started at the Gloucester end, had only reached Hardwicke a mere 5 miles away and the cash had run out. The project was stopped and all but forgotten until 1817. That year the Poor Employment Act was passed by Parliament, authorising the government to spend money on public works to help the unemployed. The canal was one of the beneficiaries.

Telford was called in to advise and a new southern terminus was fixed on at Sharpness Point. The comedy of errors, however, continued. The new resident engineer was John Woodhouse whose work did not survive Telford’s scrutiny. He had paid an exorbitant price for building stone for the works, which might have been excusable if he hadn’t bought it from his own son. Finally, the competent Thomas Fletcher was brought in and with a big contractor, Hugh McIntosh, on the job, the canal was finally completed in 1827 – it had taken more than thirty years for a canal that was 16¾ miles long. There was one more farcical event before traffic moved on the waterway. Some local lads livened up the opening ceremony by firing an ancient cannon in salute: the whole thing blew to smithereens. Once completed, however, the canal was a great success, able to take ships 150ft long and 22ft beam.

Originally known as the Gloucester & Berkeley Canal, later changed to the Gloucester & Sharpness, the waterway was intended to take high-masted sailing ships. As a result, there are no fixed bridges on the canal, just a series of swing bridges. In this photograph, the bridge has been opened to allow a tug to pass. The bridge keepers were given little houses to live in, which looked grand with the addition of a classical portico. (Anthony Burton)

The main features along the canal are the sixteen swing bridges, each of which had a bridge keeper, who lived in a little cottage next to his work. These are curious buildings, small but given an air of grandeur by elaborate porticos at the front. The docks at both Gloucester and Sharpness developed into impressive complexes with great ranges of warehouses. Sharpness became so important that in 1871 the basin was enlarged and a new ship lock was built to take vessels up to 320ft by 60ft. The canal had achieved exactly what its promoters had hoped for. It brought extra trade and prosperity to the River Severn and commercial traffic still travels as far as the basin at Sharpness. The same could not be claimed for the next canal.

A large dock complex was developed at Gloucester, with ranges of imposing warehouses. Sailing cargo ships were still using the docks as recently as the 1920s when this photograph was taken. Today commercial traffic has ceased and the dock area has been redeveloped as a shopping complex, but is also home to a waterways museum. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

As at the northern end of the Gloucester & Sharpness, so at the southern end at Sharpness, where the canal joins the tidal Severn, extensive development has continued since the canal was built. Unlike Gloucester, Sharpness still enjoys commercial traffic. The vessel in the dock has arrived with a cargo of timber from Scandinavia. (Anthony Burton)

It began in 1801 with a letter to Thomas Telford from Nicholas Vansittart of the Treasury, asking him to go to Scotland to rescue the local fishing industry. This was only part of the problem facing a country ravaged as recently as the 1740s by civil war and the attempt to restore the Stuart monarchy. The Highlanders’ wretched existence was made worse by the Highland Clearances that were removing crofters from the land to make way for sheep farming on large estates, mostly with absentee landlords. Telford reported that the industry needed new, modern harbours but the country was also suffering from poor communications. He suggested building harbours and roads – and also a new canal. These schemes would not just improve transport but also provide much needed jobs for the impoverished Highlanders.

The proposed canal, called the Caledonian Canal, would cut across Scotland from coast to coast and allow vessels to avoid the long and often dangerous passage round the north coast. It would be a ship canal, able to take the largest fishing boats then in use. The idea was to finance it with government funds, if it could be convinced it was worth the effort. Telford’s argument was that poverty was forcing families to leave the country to settle overseas, especially in Canada. Three thousand had left in the year of his survey and he wrote: ‘I am reliably informed three times that number are preparing to leave in the present year.’ The government agreed and officially approved the Caledonian in 1803.

The Caledonian Canal was part of a wider scheme for economic renewal of the Scottish Highlands, which also included road building and harbour construction. Telford came on regular inspections of all the works. This sketch shows him being driven in a gig to the canal workings. An important part of the scheme was to provide employment for the Highlanders, who can also be seen at work. (A. D. Cameron)

There is an obvious route for a canal across Scotland. It would join Fort William to Inverness. Loch Linnhe bites deep into the coast to the west, the Moray Firth to the east. In between is a natural fault line, where Ice Age glaciers have carved out the deep hollow of the Great Glen. Stretched along its length is a string of lochs: Lochy, Oich and Ness. These natural waterways could be stitched together by the artificial canal to form the through route from coast to coast. Jessop was also involved in the detailed planning, and as the reports were signed by both men it is difficult to determine who took the leading role. Jessop was the senior of the two, but Telford had spent more time going over the ground. Whoever was responsible, the plans were for a canal on a most impressive scale. Although originally planned with the fishing industry in mind, war had once again broken out with Napoleonic France, and now it needed to take naval vessels as well. Locks were now designed to be 170ft by 40ft and the canal was broadened to 100ft. This was going to need engineering works on an unprecedented scale.

Telford faced a problem from the start. By now, British canal constructors were relying on the hardened, tough professional navvies for the toughest tasks, but Telford was committed to using local labour, and most of the Highlanders who came to the works were often both inexperienced and undernourished. A few Scots had already done canal work in England, and Telford hoped they would ‘prove useful examples to others’. But there was no great incentive for experienced navvies to travel to the Highlands. In England the going rate was 2s 6d per day (roughly £10 per day today) but on the Caledonian they were only getting 1s 6d (£6.50). Nevertheless, there was no shortage of men desperate for employment. But, unlike on earlier canals, Telford did not have to rely on muscle power alone: machinery helped, and we have a more detailed account of how the works seemed than for any other canal of the age. Telford submitted annual reports to the funding body, and there is also an eye-witness account of what the workings looked like at their busiest time. This is thanks to Telford’s friend, the poet Robert Southey, who was given a tour of all the main sites and wrote detailed notes on what he found. Machinery was needed simply because of the difficulties that had to be overcome.

Sea locks had to be built at either end to allow vessels to enter the canal at high tide. The work was begun at the western end, where the lock chamber had to be cut out of solid rock that had to be excavated using hand drills to bore holes for black powder. A coffer dam was built by driving iron piles into the seabed, and the space was kept clear of water by means of a Boulton and Watt steam engine. For more than two months, 200 men worked on the site. Completing the sea lock was only the start of the problems. The River Lochy had to be diverted into a new channel to allow the canal to reach Loch Lochy. But before that point the canal had to be brought over rising ground, first by a double lock and then by a great staircase of eight interconnected locks lifting the canal by 64ft. The ironwork for the massive gates was shipped all the way round the coast from Derbyshire and when the locks were completed the gates themselves were opened by a team of men working capstans. We don’t have figures for how much the original gates weighed, but the current gates are 22 tonnes each.

The most prominent feature at the western end of the canal is the set of interconnected locks, known as Neptune’s Staircase. In this photograph, taken in the early twentieth century, the locks were still manually operated. To open and close the lock gates, the pairs of poles seen sticking up in the air were inserted into capstans. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

The Caledonian Canal never achieved one of its main objectives – to provide a safe passage for naval vessels between the Irish Sea and the North Sea. It did, however, prove useful for the fishing fleets that followed the shoals of herring and allowed them to avoid the long and difficult journey round the north coast. Here the boats are lined up along the eastern end of the canal at Clachnaharry. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

Two more locks were needed to take the canal up to the level of Loch Lochy, but at the far end of the loch an even greater obstacle had to be overcome. Only a narrow strip of land separates this loch from the next, Loch Oich, but it rises steeply. It was decided to carve through it in a deep cutting at Laggan. This was one of the busiest spots on the canal during the construction period. The hundreds of men who worked here lived in rough encampments amid ramshackle timber stores and temporary homes for the overseers. By this time there were well over a thousand men at work on different parts of the canal, and provisions was a major problem. The company provided oatmeal at what was described as ‘prime cost’ and at one site, a brewery was installed, with the optimistic hope, in Telford’s own words, ‘that the workmen may be induced to relinquish the pernicious habit of drinking whisky.’ Southey described the scene at Laggan from his journal of 1819:

Today the Caledonian Canal is used almost exclusively by pleasure boats. Yachts cram into the locks at Fort Augustus. The five-lock staircase joins the artificial canal to Loch Ness. The capstans seen in the earlier photograph have long been disused and the lock gates have all been mechanised. (Anthony Burton)

‘ Here the excavations are what they call at “deep cutting”, this being the highest ground on the line, the Oich flowing to the East the Lochy to the Western Sea. This part is performed under contract by Mr. Wilson, a Cumberland man from Dalston, under the superintendence of Mr. Easton, the resident engineer. And here also a Lock is building. The earth is removed by horses walking along the bench of the Canal, and drawing laden cartlets up one inclined plane, while the emptied ones, which are connected with them by a chain passing over pullies, are let down another. This was going on in numberless places and such a mess of earth had been thrown up on both sides along the whole line, that the men appeared in the proportion of emmets to an ant-hill, amid their own work. The hour of rest for men and horses is announced by blowing a horn; and so well have the horses learnt to measure time by their own exertions and sense of fatigue, that if the signal be delayed five minutes, they stop of their own accord, without it.’

This was a more sophisticated system than the barrow runs common on other sites. The cutting ends at Loch Oich, but even here work was needed to deepen the lock, as Southey noted:

‘ At this (the Eastern) end of Loch Oich a dredging machine is employed and brings up 800 tons a day. Mr. Hughes who contracts for the digging and deepening, has made great improvements in this machine. We went on board, and saw the works; but I did not remain long below in a place where the temperature was higher than that of a hot house, and where machinery was moving up and down with tremendous force, some of it in boiling water.’

The next section of canal was mostly straightforward, although Southey described a few difficulties:

‘ The Oich has, like the Ness, been turned out of its course to make way for the Canal. About two miles from Fort Augustus is Kytra Lock built upon the only piece of rock which has been found in this part of the cutting – and that piece just long enough for its purpose, and no longer. Unless rock is found for the foundation of a lock, an inverted arch of masonry must be formed at very great expence, which after all is less secure than the natural bottom.’

Southey also described how, at Fort Augustus, the canal plunges to Loch Ness in a spectacular staircase:

The two great staircases are the most obviously imposing feature of the Caledonian Canal. In engineering terms, the greatest challenge was creating the deep cutting at Laggan, carved through the narrow neck of land separating Loch Oich from Loch Lochy. It is difficult now to see the scale of the operations, as the banks are overgrown with trees, but some idea can be judged by the way in which the banks seem to dwarf the cabin cruiser. (Anthony Burton)

‘ Went before breakfast to look at the Locks, five together, of which three are finished, the fourth about half-built, the fifth not quite excavated. Such an extent of masonry, upon such a scale, I have never beheld, each of these locks being 180 feet in length. It was a most impressive and rememberable scene. Men, horses and machines at work; digging, walling and puddling going on, men wheeling barrows, horses drawing stones along the railways. The great steam engine was at rest, having done its work. It threw out 160 hogs heads per minute [approximately 10,000 gallons] and two smaller engines (large ones they would have been considered anywhere else) were also needed while the excavation of the lower docks was going on: for they dug 24 feet below the surface of water in the river, and the water filtered thro’ open gravel. The dredging machine was in action, revolving round and round, and bringing up at every turn matter which had never before been brought up to the air and light. Its chimney poured forth volumes of black smoke, which there was no annoyance in beholding, because there was room enough for it in this wide, clear atmosphere.’

Southey’s descriptions hint at the mechanisation that had arrived in canal construction in the early nineteenth century. Steam engines kept the sites free of water and steam dredgers deepened the lochs. At Fort Augustus the canal entered Loch Ness, and from the far end of the loch it was only a short way to Inverness and beyond that to the coast at Clachnaharry. Unfortunately, however, the shoreline at this point has a gentle slope, so that deep water is only reached some distance from the coast. It was necessary to build an embankment out into the sea. Clay was dug out of a nearby hill and brought to the site on a specially constructed iron railway. This material was built into a bank that stretched out to sea for 400yds. Stones were laid on top and it was then allowed to settle for six months. Once the bank had been consolidated, the sea lock was built at the end. At first the site was kept pumped dry using a bucket dredger operated by a team of horses, but as the pit was sunk ever deeper into the bank, a small steam engine was brought to the site.

The canal finally opened in November 1822 but, by this time, Telford had already been at work on another ship canal in Sweden.

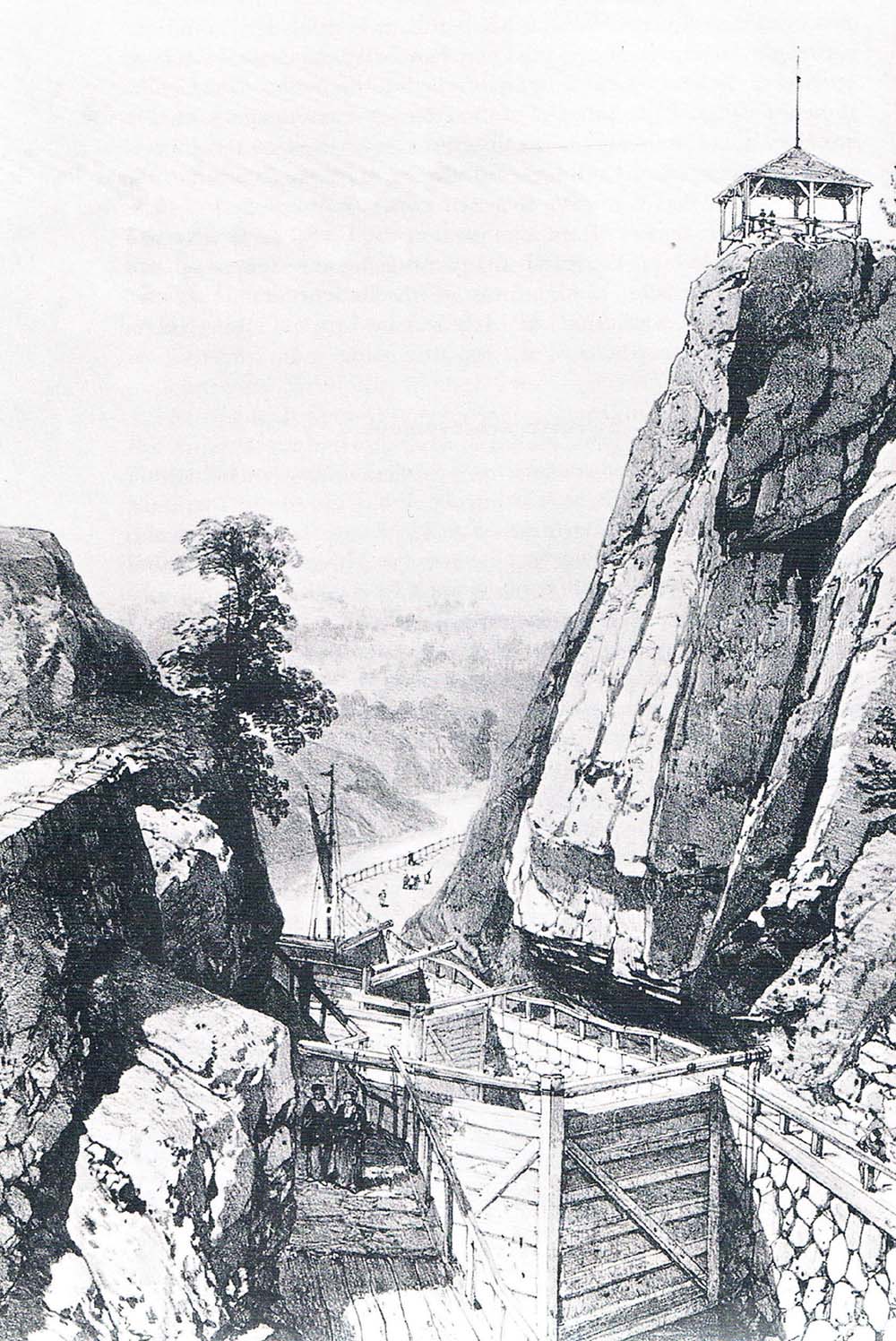

The idea for a canal that would cut across Sweden from the North Sea to the Baltic had been around for a long time. There was an obvious route that would connect a string of lakes, much as the Caledonian had done. A start was made as early as the sixteenth century when Gustavus Vasa planned to link Stockholm to the Göta River. The Eskilstuna River was canalised with the construction of eleven timber locks, linking two of the lakes, Hjälmaren and Mälaren, and was completed in 1610. In 1617 Dutch engineers improved the navigation on the Göta River. Things were moving forward, but the first canal proved unsatisfactory. Further sections were completed over the years, but the biggest obstacle was always the section between Lake Vänern and the Göta. Water from the lake entered the river via an imposing waterfall at Trollhättan. Work continued on improving the Göta, but the falls proved a major obstacle, and for years goods had to be carried round by land. The problem persisted right up to 1790 when a new company was formed to solve the problem. The engineer was variously known as Erik Nordwall and Nordewall. His answer was to carve a way through the rocks to create two lock staircases, one of three locks and one of five, to raise the waterway up to the level of the lake. A short section of canal was then cut to reach the lake itself. This new canal was named after the town, the Trollhätte Canal.

The older navigation attempts had not been successful but a new personality drove developments forwards – Count Baltzar von Platen. He was a naval officer who had risen to the top of the Swedish navy and, on his retirement, took a keen interest in improving navigation. He had been one of the men behind the Trollhätte Canal and now he wanted to extend it across the country to complete the system that had been thought about but not finished for two centuries. The man he looked to was a Norwegian engineer, Samuel Bagge, but Bagge didn’t feel up to the task. In 1808 von Platen discussed his plans with King Gustav IV who issued a royal decree requesting Thomas Telford to take on the task. von Platen translated the document into wayward English. It requested Telford ‘to take a vieu of this undertaking and give his opinion and council thereupon’. Getting the communication to Telford proved problematical as the engineer was travelling from canal works to canal works. von Platen began a long correspondence with the engineer, which began in typically chatty fashion: ‘You will I hope excuse me for introducing myself quite a stranger to You in this manner and I fear in Englisch is not the best sort.’ Imperfect it may have been, but Telford’s Swedish was non-existent. It is clear from the early exchange of letters that Bagge must have visited the works on the Caledonian and held Telford in high regard, which made their eventual working relationship that much easier.

The locks of the Trollhättan Canal that lift it from the level of the River Göta to Lake Vanern. The work began in 1790 under the direction of the engineer Erik Nordewall. He carved his way through solid rock to create two lock staircases: one of three locks and one of five locks. In time these proved inadequate and were replaced by a single staircase, built alongside the original. Finally, in the twentieth century they too were replaced by one giant lock, 9m deep. All three sets can still be seen at the site, although the original locks are now gateless and derelict. (Anthony Burton)

It is remarkable that a canal was even being contemplated when Europe was still convulsed by the Napoleonic Wars. Other Scandinavian countries and Russia had signed a peace treaty with France but Sweden opted out, fearing the spread of revolutionary ideas. Russia decided that Sweden could be treated as an enemy state and seized Finland. Bagge was placed in a most awkward position. As a Norwegian, he too was officially a citizen of an enemy country, even if Norway and Sweden weren’t at war. He had to leave the country. It also meant that the seas around Scandinavia were dangerous. Telford accepted the invitation to visit Sweden, but only if he could be assured a safe passage:

‘ But these Northern Seas are at present much infested with Danish and French privateers this makes a passage in a common trading Vessel to be attended with a risk from these armed Vessels – however trifling. I must therefore stipulate that I shall be taken up at Aberdeen and also landed at the same Place by either a Swedish or English ship of War.’

Telford ordered provisions for himself and his two companions for the journey, and the list is now framed and hung in the restaurant at the Institution of Civil Engineers. It included two dozen bottles of Madeira and the same of port; three dozen of cider; six dozen of porter; and half a dozen each of gin and brandy. This was balanced by copious quantities of tea, and there was also an order for 31½ pounds of lump sugar.

Telford duly arrived in Sweden and toured the likely route of the canal. Although, as with the Caledonian, the canal was only needed to link a series of navigable lakes, the problems were far greater. The canalised section ran for 53 miles, more than twice that of the Scottish canal, and the summit was higher at 85m (278ft). The descent from Lake Vattern would require fifteen locks, which Telford suggested should consist of four linked pairs and a seven-lock staircase. In view of the difficulties involved and the almost complete absence of workers skilled in canal construction in Sweden, the engineer felt that it was impractical to build on the scale he had used in the Highlands. The locks would be 32m by 7m (105ft by 23ft).

Telford completed his survey, establishing a real friendship with von Platen and returned to Scotland. There was now a major political upheaval. The King was held largely responsible for the debacle over Finland and was deposed in favour of a new ruler, the former commander-in-chief of Norway, who now became King Charles August. Positions were now reversed: Norway was a friend and Bagge could return to take charge of the workings, whereas Telford was now officially the citizen of an enemy country. In practice, this made no difference to Telford’s position, and Bagge made his own situation clear:

‘ I don’t wish to take orders from any man except you or the Baron [von Platen]. It was not for the sake of profit nor for the sake of commodity I did leave Norway, but you know the project has always laid at my heart … Neither trouble nor reflection should be spared in exercising your orders.’

Although Bagge was full of good intentions, he sadly lacked experience. His large workforce consisted of 900 soldiers, 200 labourers and 150 Russian captives who Bagge described as having ‘defected on the road home being tired of their despotic government’. But they were no more experienced than the man in charge. Bagge constantly wrote to Telford, begging for advice and help. He asked for experienced workmen, especially those used to puddling as no one in Sweden knew the process apart from himself, and he had only a vague recollection. He also asked for masons and the necessary tools and equipment. Telford sent various items, including rails, wheelbarrows, picks and shovels for Bagge to copy, as well as detailed engineering drawings.

By 1812, the main workforce consisted of 5,000 soldiers spread out along the line. Things were going well when tragedy intervened: Bagge drowned in a boating accident. The British supervisors took over much of the work done by Bagge, but not without friction, particularly with one man, Simpson, who antagonised the workers by drinking with them, but without ever paying his way. This caused von Platen grief, but work went ahead. Major decisions needed to be taken.

Many of the canal fixtures, such as lock gates and movable bridges, were designed to be made from cast iron. Sweden had a long history as a provider of wrought iron of the finest quality, but there was no expertise in foundry work. They could all have been manufactured in Britain, but von Platen saw the opportunity to create a new industry for his country. With help sent from Hazeldine, the company that made so much ironwork for Telford, a foundry was established beside the canal at Motola, which became the centre of a large and important industrial complex. Work on the Göta Canal was not immune from the shortage of funds that plagued so many other canal schemes. von Platen bore the brunt of criticism when costs overran estimates, although given the size of the task and the inexperienced workforce, no one should have been too surprised. He sent a long letter to Telford in which he spoke bitterly of the charges against him, but ended on a positive note by pointing to two things: the critics could never get rid of his ‘calmness and tranquility’ nor could they stop ‘so large an undertaking in so many ways connected with general welfare, after it was so far advanced’. He got the funds to finish the job.

The Trollhättan Canal still carries commercial traffic. This ship has arrived from Göteborg and is negotiating the narrow final section of canal that runs from the top of the locks to Lake Vanern. (Anthony Burton)

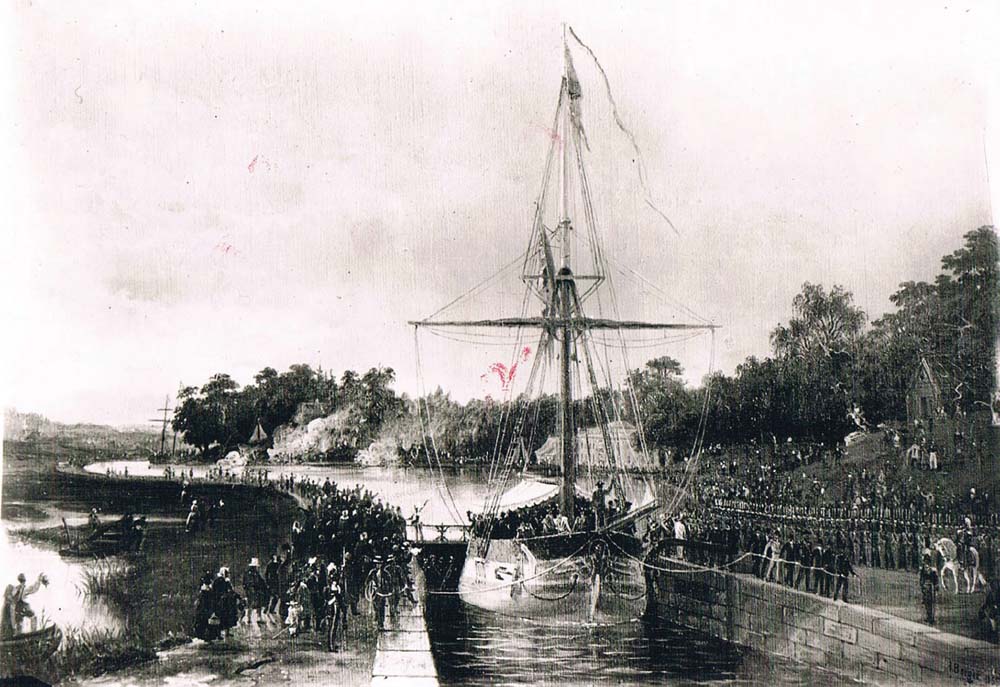

The canal was finally completed in 1832 and to mark the occasion, the royal yacht Esplandian made the trip from coast to coast. Sadly, the men who had worked so hard to achieve this were not there to see it. Telford was 70 years old and not ready to make the long sea crossing; von Platen had died at the end of 1829. The canal proved an immense success, so much so that the original locks at Trollhättan had to be enlarged at various times to take ever larger vessels. Visitors to the site today can see the derelict remains of the original locks, their nineteenth-century replacements that are still in use by small craft and the single ship lock for larger vessels with a massive 9m drop. Paradoxically, it is the older Trollhätte Canal that still has a busy commercial carrying trade, with cargo ships passing through it to the industrial sites around Lake Vattern on a weekly basis.

The three ship canals suffered varying fates. The Gloucester and Sharpness thrived for a long time, and Gloucester developed into a major inland import, with docks surrounded by imposing warehouses. Those days are over, but Sharpness remains an active port; as a whole the waterway can be deemed a success. The Caledonian never lived up to its promise. The expected use by naval vessels never happened, mainly because the end of the Napoleonic Wars ended the threat to British shipping for many years. Its main use was by the fishing fleets, moving from coast to coast, and today its traffic consists almost entirely of pleasure craft. It did, however, succeed in one of its objectives – in providing much needed work for the hard-pressed Highlanders. The Göta Canal proved in many ways the most successful of the three, not only providing a much needed cross-country route but also acting as a powerful stimulus to new industries. All three did, however, have one thing in common: they extended the boundaries of canal construction both in terms of size and technology.

The continuation of the route from Lake Vanern to the Baltic Sea was accomplished with the building of the Göta Canal under the direction of the chief engineer, Thomas Telford. The painting by Johan Christian Berger shows the grand opening of the canal on 26 September 1832. The royal yacht Esplendian is passing through the sea lock at Mem on an inlet of the Baltic. (The Göta Canal Company)

So far we have mostly looked at canals in Europe, but across the Atlantic a major canal network was also being developed.