Ideas for canal construction in North America were being put forward long before the US gained independence, leaving the British only in control in Canada. The first advocate for an artificial waterway was an unlikely candidate for the role – a Catholic Priest, Louis Joliet. He was born in Quebec in 1646 at the heart of French Canada and took holy orders, but his early enthusiasm died rapidly and, after just four years, he quit the priesthood to become a fur trader. This involved extensive travel and in 1673 he was appointed to find connections from the north down to the Mississippi. He and his companions found their way to the great river, joining it at what is now Memphis. It was a genuinely epic adventure and for much of the return journey they made their way back by water, joining first the Illinois River and then a tributary, the Des Plaines, before a short portage brought them to the Chicago River and on to Lake Michigan. Joliet’s report pointed out that by digging a short canal, Lake Michigan could be joined to the Illinois to create a mighty continuous water system from Canada all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. The idea made a lot of sense and a canal was built on the line suggested by Joliet – but not until 1827.

The other idea mooted at much the same time was for a canal through the narrow neck of land joining the mainland to Cape Cod, that crooked finger of land pointing out into the Atlantic between Boston and New York. Samuel Sewell, a merchant from Sandwich, recorded in his diary for 26 October 1676 that a neighbour had shown him where the canal should be built. Again, nothing happened simply because the costs were prohibitive. At this time in the late seventeenth century, the population of the region was too small to support such an ambitious scheme. This scheme was finally put into practice in 1914. Canal construction was put to one side for another hundred years, and only really got under way after America had won its independence: by 1790 the young United States saw thirty canal companies being formed in eight of the original thirteen states. They were partly financed by the government, which over the years invested almost $400 million, but even that was dwarfed by the thousand million dollars put up by private investors.

The development of North America transport is inextricably tied to the continent’s great rivers, such as the Mississippi, Missouri and, north of the newly defined border, the St. Lawrence. The idea of linking the rapidly developing major towns to the rivers by means of artificial canals was attractive, but there was a problem: few, if any, Americans had experience of canal construction. The problems are exemplified in the first major canal project in the fledgling US – the Middlesex Canal.

The canal was to link Boston to the Merrimack River at Chelmsford and the canal company received its charter in 1793. The principal promoter was Judge James Sullivan, the son of Irish immigrants, later to become governor of Massachusetts, and the job of superintendent went to Loammi Baldwin, who had been a colonel in the War of Independence. Baldwin had great energy but no knowledge of canal construction. He took himself off to Harvard University to study all the available books on English canals: he was about to undertake the construction of a major canal without having ever seen a lock except as an illustration in a book. He was in desperate need of a competent surveyor, but the only man he could find was a self-taught surveyor from his hometown of Woburn, Samuel Thompson. Thompson had little surveying equipment, but he and Baldwin set out to survey a likely route. Baldwin recorded in his diary that they met ‘insurmountable obstacles’. These did not deter the party, but more worryingly the levels that Thompson took were hopelessly inaccurate. He recorded the rise from Boston as 68½ft, where it was actually 100ft, and the rise from the Merrimack as 25ft instead of 41½ft. Fortunately, Baldwin did not trust the results and turned to the only man he knew with experience of canal work, an English engineer called William Weston. The route was surveyed again and the errors corrected.

The 1822 painting by Jabez Ward Barton from the Billerica Historical Society Collection shows the Middlesex Canal at the point where it crossed the Concord River. A lock can be seen in the distance, by the horse. The more distant horseman, next to the boat, is trotting across the floating towpath that allowed boats to be towed by horses across the river to rejoin the artificial canal. The section on which the horseman is shown is actually a drawbridge that could be lifted to allow river traffic through. (Billerica Historical Society)

Work now went ahead on laying out the line of the canal and working out the required structures. There were to be two sources of water. The first was the Concord River that was to be crossed on the level, which presented an interesting problem. Traffic on the canal would be moved in the conventional way – barges pulled by horses – but how would they cope with the river crossing? The ingenious answer was to build promontories and the space in between was filled with a floating towpath. At the summit, water was supplied by Horn Pond. The company bought the existing grain mill and a small industrial complex grew up at the site that is now home to a canal museum. The twenty locks were built to generous proportions, 80ft long and up to 12ft wide. Most were built of stone, made watertight by hydraulic cement derived from volcanic material imported from the West Indies. This was effective but expensive, so some were constructed from wood. The canal was 27½ miles long and at one time there were 500 men at work. The ordinary labourers were paid $8 a month, roughly $110 at today’s prices – unlike the British navvies who expected higher rates than usual for this specialised work, their American counterparts were paid the standard rate for the period. Skilled workers, such as stonemasons and carpenters, were paid $15 a month. The pay seems very low, but the company gave the men shelter and provisions. It was necessarily seasonal, with everything stopping in the freezing winters. The canal was completed at the end of 1803 and was a great success. Traffic on the canal was mainly in flats hauled by mules, occasionally hoisting a simple sail, and a regular passenger service was introduced from the start.

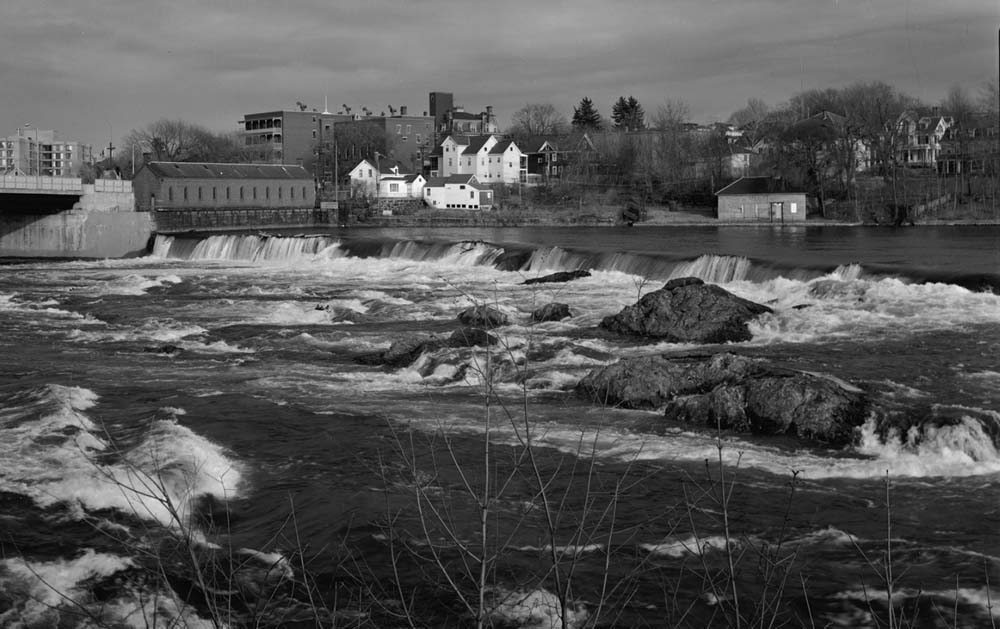

The photograph shows the falls on the Merrimack River. On the far side one can see the entrance to the Pawtucket Canal beside the long single-storey building, the gatehouse. This controlled the flow of water from the river into the canal system. When Francis Cabot Lowell came here in the early nineteenth century the canal system played an important role in bringing water to turn the wheels of his new textile mill in what was to become the city of Lowell, Massachusetts.

The Middlesex Canal was not the only scheme considered for joining the Merrimack to the coast. The Proprietors of Locks and Canals on the Merrimack River also planned a canal to Newbury Port, but the Middlesex beat them to it and the earlier plan was dropped. But the men behind the other scheme had not given up. They developed the Pawtucket Canal, built to bypass the mile of falls and rapids near Chelmsford that dropped the river by 35ft. It proved far more valuable than they could have imagined. The textile industry of America was still in its infancy at the end of the eighteenth century, and although powered machines were taking over all the old processes carried out by hand by workers in their own cottages, the British tried their best to keep the details secret. Inevitably they leaked out, and one man who visited textile mills in England carried away in his head the details of the new power looms. His name was Francis Cabot Lowell and in 1814 he arranged for the first power loom to be built in America. Satisfied that it worked, he planned an industrial complex with a mill that would combine spinning and weaving. It was a small beginning but from it the great textile town developed that would bear his name, Lowell. The existing canal system was essential for its success and Lowell developed a new canal to bring the water from above the falls to power the mills of the new town. Unlike much of the American canal system, the canals of Lowell still survive.

This illustration gives a closer view of the gatehouse seen in the previous photograph. Inside the gatehouse are a series of heavy sluice gates that are raised or lowered, using a water turbine for power. To the right of the building is the barge lock. The canals of Lowell are unusual in being both transport routes and power sources, although today they are only used by tourists. (Miss E. M. Waine)

It is an interesting and instructive story. In Europe, canals had mainly been built to serve existing industrial complexes. Here, the Middlesex Canal was mainly intended to bring primary produce such as timber to the developing towns and cities of Massachusetts. But once the canals existed, they served as a catalyst for industrial development.

Many of the earliest developments, although given the name of canal, were little more than river improvements, short stretches of artificial waterway built as lateral cuts to overcome difficult sections of the river. The Connecticut River was typical of such schemes. The river was an important trade route, but navigating it was difficult and arduous. The craft in use in the eighteenth century were mainly flats, poled up the river or drifting down with the current, and there were portages round the most difficult sections. The first major improvement was the construction of the South Hadley Falls Canal. Work began in 1793 and although it was just 2 miles long, it was a major engineering feat, involving carving a cutting 40ft deep and 300ft long through solid rock. Instead of locks, the difference in levels was overcome by an inclined plane. This was 230ft long with a vertical drop of 53ft. Instead of a railed track, as on the British planes, there was a stone ramp, covered by heavy planks. The caisson consisted of a wooden box, with folding gates at both ends. This would be lowered into the canal, the boat would float in, the gates would be closed and then the water would be drained out through sluices. Two water wheels, fed by canal water, raised or lowered the caisson, which was mounted on three sets of wheels of different sizes to keep it level when on the slope. This was a larger version of the devices used on the barrow runs on the Caledonian Canal, described on p117.

Although boatmen welcomed the canal, it was bitterly opposed by other interests, a scenario all too familiar to Europeans attempting river improvements. Fishermen complained that the dam, built to divert water to the canal, stopped salmon going upstream and mill owners claimed their water supply was affected. The canal company compromised and lowered the dam, but nature had the last word: the rebuilt dam was washed away in a flood. It was replaced, but went the way of the second. The canal company abandoned the struggle.

The next obstacle was the Bellows Fall in Vermont. Once again this was a short canal but with a lot of engineering packed into it. The falls had a drop of 50ft, so the mile-long canal actually had nine locks. As the nineteenth century dawned, work began on another heavily locked canal round the Montague Falls, with eight locks in 3 miles. The last and longest of the canals was the 6 mile Windsor Locks Canal, opened in the 1820s. At the end of the navigation a new town grew up. It was here that the river men, the timber-raft men and the powder men, transporting barrels of gunpowder, met and often quarrelled that ended in brawls. It was not a tranquil spot in its early days – a sprawling township of bars and brothels – but it gradually developed respectability. The canal may have disturbed the peace of this part of the country, but it made the investors happy, regularly returning handsome dividends. The canal is still in use, but now only by pleasure craft. Over a quarter of a century of construction, the Connecticut River had been tamed.

River improvement by building short stretches of canal spread across the country’s inhabited regions in the east. One such scheme developed over the years from this system to what would become one of America’s most imposing canals – the Chesapeake and Ohio. It began with the work of America’s most famous hero, George Washington. The Potomac River was largely unnavigable in the early eighteenth century, with two major obstacles in the form of the Great and Little Falls, some 14 miles upstream from what is now Washington DC. George Washington introduced a Bill to the Virginia burgesses in 1774, calling for improvements to the river, but it was rejected because most of the delegates didn’t see their constituents benefiting. Washington had another try, this time adding improvements to the James River, but before anything could be done, the war against British rule began and Washington had other matters to attend to. With peace and independence in 1783, Washington again campaigned for improved transport in the infant United States and, in particular, with connections with what was then referred to as the Ohio country. In 1784 he set out his ideas in a letter: ‘Extend the inland navigation of the eastern waters; communicate them as near as possible with those that run westward; open these to the Ohio; open such as extend from the Ohio towards Lake Erie.’ It was ambitious, but an essential part of the steady development of new territories being opened for settlement as emigrants moved ever further west.

Washington received enthusiastic support from the Governor of Virginia, Benjamin Harrison. He persuaded Washington to explore up to the headwaters of the Potomac, then known as the Patowmack, in the Appalachians and beyond to investigate the river systems on the far side. He set off in September 1784 with just one servant as company and, together on foot and horseback, they journeyed about 650 miles, during which they travelled along the Shenandoah and from there crossed to the Allegheny, eventually reaching the junction with the Ohio River. He reported back to Harrison and the result was the formation of the Patowmack Company, authorised to improve the river with a series of short canals, built to bypass the worst obstacles. If the scheme proved successful and the shareholders received a satisfactory return on their investment, which was considerable as shares were $400 each, then canal construction would be extended to other regions.

In 1784 Washington stayed at an inn at Bath, now Berkeley Springs, West Virginia. The owner, James Rumsey, who was also a builder and inventor, showed Washington a model of a boat he had devised to travel on the Potomac. It had a bow-mounted paddle wheel that operated poles that would lever the boat along against the current. Washington was impressed and when work started on improving the Potomac at Harper’s Ferry he put Rumsey in charge of clearing rocks. As the canal scheme advanced the lack of engineers with experience in canal construction in the country became a real problem. Rumsey was made chief engineer. He had realised his original model was impractical and devised ways to work it by steam instead of by water power. We shall return to Rumsey’s experiments later, but in the meantime, he was occupied with building a canal, for which he had no experience whatsoever.

Rumsey not only had the problem of blasting a passage through rocks beside the Great Falls and building locks to overcome the change in level but also coping with an inexperienced workforce. The men were a strange mixture of slaves, indentured workers and Irish immigrants. They received a daily rum ration, which the Irish found ways of supplementing as no doubt many were used to making illegal poteen. There were many drunken brawls. The indentured labourers were always trying to escape, and those caught were marked as troublemakers by having their heads shaved. Nevertheless, the work went ahead. Rumsey built a total of five lateral canals, the longest of which was three quarters of a mile long beside the Little Falls, but the most imposing was the Great Falls bypass with a flight of five locks and a deep cutting through a rock gorge. It had taken a lot of time, the money was all spent and attempts either to sell new shares or to get government finance both failed. The Pawtucket Company was wound up and a new company with an even wider brief was formed in 1824 – the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company.

Originally the canal was planned in three sections: the eastern from Georgetown on the Potomac to Cumberland; the middle crossing the Continental Divide; and the western that would end at Pittsburgh. Engineers estimated the total cost at more than $22 million, which investors thought was ludicrously high. The eastern section looked reasonable because, although it would be a long canal of 186 miles, it only needed seventy-four locks. The greatest difficulties were in the middle section, where the total ascent and descent totalled 1,961ft and involved building 246 locks in just 70 miles. The western section was less problematical, with 78 locks in 85 miles, but without the problematic middle section it had no value. It was decided to start on the eastern section to see how things went, and a new estimate came in at more than $5 million for the eastern part, which seemed much more manageable. It proved, like so many other canal contracts around the world, very optimistic.

Work began on the canal that was to link the Potomac to the Ohio, with suitable celebrations and euphoria, on an obvious date for patriotic Americans – 4 July 1828. The enthusiasm was misplaced: it took the next twenty-two years to complete. The company constantly ran out of money and got deeply into debt, largely because of the exorbitant prices land owners along the route demanded to allow the canal across their holdings. There was also no shortage of engineering problems. Much had been made in the original reports of the need for lock construction, but not much emphasis was placed on building eleven aqueducts along the route. They were mostly conventional structures, the longest (the Monocacy) being 516ft long. The Seneca aqueduct, however, was unusual in that it was also a lock. Apart from the aqueducts there was also the 3,118ft long Paw Paw tunnel. But the greatest challenge was not on the canal itself.

The unusual aqueduct bridge across the Potomac. It had originally been planned to end the Chesapeake and Ohio canal at Georgetown, but Alexandria, across the river in Virginia, had contributed greatly to the funds and they demanded a connection to the canal. The result was this unusual structure that served both as a roadway and canal aqueduct. Sadly this interesting structure has not survived. (Library of Congress)

Alexandria, on the western bank of the Potomac, had contributed $250,000, hoping to make a direct connection to the proposed canal. This would have involved an aqueduct across the river, which was deemed too expensive. By 1830, however, attitudes had changed and the Alexandria aqueduct was authorised. It was remarkable. It had eight spans supported by massive stone piers set on the bedrock, with their tops 30ft above the high water mark. During the spring thaws, massive ice floes would sweep down the river, so to protect the piers granite ice breakers, like the more familiar cutwaters on bridges, were built out from the piers. Unlike conventional aqueducts, the superstructure was built out of stout timbers, with a wooden trough and a narrow carriageway alongside it. This is why the Alexandria is usually referred to as an aqueduct bridge. Built to serve the southern state of Virginia, it was used against the south in the Civil War, when the trough was drained and used as a bridge for Union troops.

The canal finally reached Cumberland in 1850 and in spite of the delays and financial problems, it was an undoubted success, with income from tolls reaching a million dollars in bumper years. It was never, however, extended westwards: by 1850 the world of transport was changing.

Among the many small canals built during the first great period of canal construction, one major undertaking stood out both because of its size and its importance in opening up the country. The Erie Canal, originally known as the New York Canal, was designed to join Albany on the Hudson River to Lake Erie. From Albany, barges could continue on the Hudson to New York. Like the Chesapeake and Ohio, there was a long time during which schemes were put forward without anything happening. This is hardly surprising. It was hugely ambitious and being promoted in a comparatively thinly populated country with little expertise in civil engineering. The idea was proposed in the New York State Legislature in 1808, which led to the formation of the New York Canal Commissioners (NYCC). They hoped to get funds from the United States Congress, but were unsuccessful. They still went ahead with surveys, athough there was an interruption to the work when war broke out with Britain, which of course included the British colony of Canada, and the US, and only resumed in 1814 when the peace treaty was signed.

The Erie Canal at Lockport, looking down the double sets of five-lock staircases. These were cut through solid rock and carried the canal down the Niagara escarpment. (New York Public Librarie)

The reports of the NYCC indicate the difficulties encountered by the surveyors in what was to a large extent virgin territory:

‘ In exploring the route of the canal, in a country but partially cleared, it was impossible for the engineer, in first running over it, to determine in many places, where the canal line would pass. After advancing some distance in a doubtful course, difficulties would be met which made it expedient to go back upon the line to some point, whence a more eligible course might be pursued.’

The engineers had many concerns, not least water supply. A later report pointed out that if they relied on rivers, the canal was liable to be inundated with the floods that followed the thaws in spring and would suffer from shortages in the autumn. Because of the severe weather conditions, large parts of the canal bank would have to be faced with stone to protect against gales and floods. All this added to the expense that, in the absence of support either from the government or neighbouring states, would all be met by the State of New York. In spite of all the difficulties, a route was laid out and construction finally got under way in 1817.

This was a massive project in every sense, running for 363 miles with a total rise from Albany to Lake Erie of 568ft. Engineering works included eighty-three locks and three major aqueducts. The Genesee River crossing was the most elegant, 802ft long and carried across swirling falls on nine semi-circular arches. The longest was the Cohoes at 1,188ft and the third was the more modest 744ft long Little Falls aqueduct. All three would have been considered important undertakings on any canal under construction at that time. It was decided to make the locks to generous dimensions, 90ft by 15ft, and there were two parallel sets of five-lock staircases built at Lockport. The NYCC argued that as the main cost was piling, it would not make much difference to the overall expense to make them large enough to take barges capable of carrying 30 tonnes. They did, however, indulge in cost cutting. Hydraulic cement depended on using imported material, so ordinary mortar was used, and the lock floors were made of timber: expedients that worked in the short term, but wouldn’t last. They didn’t need to last very long anyway as the planners had seriously underestimated how successful their canal would be. The locks had to be increased in size several times over the years and the channel widened and deepened until eventually it would take vessels carrying 240 tonnes.

The work was handed out to a large number of small contractors, and early on at least a large part of the workforce was made up of Irish immigrants, known by the disparaging name of ‘bogtrotters’. In some ways it was appropriate, for part of the route ran through the swamps and marshes west of Syracuse. They were paid a miserable $8 a month, and slept in crude wooden shacks – and the ‘monthly payment’ did not mean that for every month they were on site they got paid. A month to the contractors consisted of twenty-eight days when they worked – stoppages for bad weather did not count.

The conditions in summer, particularly in the marshes, were atrocious. Sickness, generally referred to as ‘swamp fever’, was endemic. It was, almost certainly, in fact malaria. Official reports put disease down to ‘the vegetable putrefaction which unavoidably takes place with the overflowing of those lands’. The annual report for 1820 described work as being held up by disease among the men:

‘ The excessive and long continued heat of the last season, subjected them to extensive and distressing sickness. Between the middle of July and the first of October, about one thousand men, employed on the canal, from Salina to Seneca river, were disabled from labor by this cause. Most of these men recovered.’

The report does not record how many failed to recover, and whether this implied that they were too sick to continue working or simply died of their illness.

Later, as work on the canal progressed, more and more men joined the workforce, many of them coming from established farms. One lesson they had learned in establishing homes in the wilderness was how to clear the land. They invented a device for pulling up tree stumps: with a team of horses and half a dozen men they could clear forty stumps a day. They also developed a quick method of felling trees, by attaching a cable to the top and winding it in with a screw. They cleared brush, by using a plough with an additional horizontal cutter. The work now moved on at a better pace. Even so it was not until 1825 that the canal officially opened. The news was relayed from end to end of the waterway in a unique fashion. Cannons had been placed at intervals of eight to 10 miles: as the first boats reached the Erie, a cannon was fired. The noise was picked up by the next down the line and so on, until the news reached Albany, when the last shot was fired.

Unlike British canals, American canals obtained a considerable part of their revenue from carrying passengers in specially designed packet boats. This painting of 1837 by George Harvey shows a packet boat on the Erie Canal at Pittsford. One can see that this was intended to be a speedy service by the three horses moving at pace, controlled by a postillion. (Memorial Art Gallery of Rochester)

The canal may have cost millions to build, but it soon showed that it was good value for money. In 1825 it brought in revenue of $495,000, more than enough to cover interest on the debt. More than 13,000 vessels of various kinds used the canal in that year and, unlike its British counterparts, there was immense passenger traffic – 40,000 passed through Utica. Its success brought an upsurge in construction in other parts of the country.

The most important venture to follow the success of the Erie was the Wabash and Erie Canal, the longest ever built in North America. It ran for more than 460 miles from Toledo on Lake Erie to the Ohio River, and when completed was part of a waterway that reached from the Canadian border to the Gulf of Mexico. The key word there is ‘when’, for although work started in 1832, it was not completed throughout until 1853, by which time it was obsolete. There were many reasons for the delay. In the early days, work was handicapped by corrupt men in charge, specifically the chairman of the enterprise, Milton Strapp, and the secretary, Dr O. Coe, who between them embezzled more than $2 million of the company’s funds. Another problem was, as on the Erie, terrible outbreaks of diseases among the 1,000-strong workforce. Cholera took a heavy toll and, according to legend, on one 40-mile stretch, a worker died for every two yards the canal advanced. As that would have wiped out the entire workforce several times over, it must be an exaggeration. But the death toll was undoubtedly high.

In the rush of canal construction following the Erie success, waterways spread over a great area of the country, the majority of the money coming from the public purse. Before work began, the NYCC had hoped to employ a British engineer to make up for the lack of local expertise. That never happened, and American canals developed in different ways from those of Britain. One notable difference was how many rivers were crossed on the level, usually by building a dam on the river to ensure a suitable depth for the actual crossing. And, as mentioned earlier, there was a very busy passenger trade, although comfort was not a prime consideration. Peter Stevenson, in his Sketch of the Civil Engineering in North America (1859), gave this account of life on a packet boat:

‘ About eight o’clock in the evening every one is turned out of the cabin by the captain and his crew, who are occupied for some time in suspending from the ceiling two rows of cots or hammocks, arranged in three tiers, one above another. At nine, the whole company is ordered below, when the captain calls the names of the passengers from the way-bill, and at the same time assigns to each his bed, which must immediately be taken possession of by its rightful owner on pain of his being obliged to occupy a place on the floor, would the number of passengers exceed the number of beds … I have spent several successive nights in this way, in a cabin only 40ft long by 11ft broad, with no fewer than 40 passengers; while the deafening chorus produced by the croaking of the numberless bullfrogs …was so great, as to render it often difficult to make one’s-self heard in conversation, and, of course, nearly impossible to sleep. The distribution of the beds seems to be generally regulated by the size of the passengers; those that are heaviest being placed in the berths next to the floor …at five o’clock in the morning, all hands are turned out in the same abrupt and discourteous style, and forced to remain on deck while the hammocks are removed and breakfast is in preparation. This interval is occupied in the duties of the toilette… A tin vessel is placed at the stern of the boat, in which everyone washes and fills for his own use from the water of the canal, with a gigantic spoon formed of the same metal; a towel, brush, and a comb, intended for the general service, hang at the cabin door.’

Charles Dickens was another who travelled by canal in America, describing his experiences in his American Notes of 1842. The sleeping arrangements were similar to those described by Stevenson, but Dickens inevitably gave a more whimsical description: ‘I found suspended on either side of the cabin, three long tiers of hanging book-shelves, designed apparently for volumes of the small octavo size… I began dimly to comprehend that the passengers were the library.’ Yet in spite of this and other discomforts, ‘there was much in this mode of travelling that I heartily enjoyed.’ He even claimed to find it invigorating to run up on deck at five in the morning, ‘scooping up the icy water, plunging one’s head into it, and drawing it out, all fresh and glowing with the cold’. But it was the travel itself, being towed along by mules, that he enjoyed most:

‘ The fast, brisk walk upon the towing-path, between “that time and breakfast”, when every vein and artery seems to tingle with health: the exquisite beauty of the opening day, when light came gleaming off from everything; the lazy motion of the boat, when one lay idly on the deck, looking through, rather than at, the deep blue sky; the gliding on at night, so noiselessly, past frowning hills, sullen with dark trees, and sometimes angry in one red, burning spot high up, where unseen men lay crouching round a fire; the shining out of the bright stars undisturbed by noise of wheels or steam, or any other sound than the limpid rippling of the water as the boat went on: all these are pure delights.’

Every canal enthusiast can identify with those words – even if most would rather get up later in the morning.

Canals were always seen as important in opening up the young US. The same could be said of Canada. Before the canal age, Canada had the rudiments of a continuous waterway system, stretching inland towards the middle of the continent, in the form of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. All that was needed was to link them together and to bypass any rapids and falls on the river. However, there were years of false starts before anything of great note was accomplished.

The first attempt to build a canal began in the days when the French controlled much of the country. The idea was to bypass the dangerous rapids north of Montreal, and because it was believed this would open up a route to China, the project was known as Canal de Lachine, the China Canal. The first plans were laid in 1689, but nothing came of them until they were revived in the 1820s by a Scots immigrant, John Redpath. It was never a complex construction problem, although it was built on a suitably grand scale to allow large vessels to use the waterway, with seven locks, each 30m by 6m, in the 14km canal. It was immediately effective in bringing trade to Montreal at the expense of Quebec, and was so successful that it had to be enlarged in the 1840s and again in the 1870s. Its commercial life ended in 1970, but it has reopened for pleasure boating.

The next attempt at canal building started in 1798 with a lock on the Sault Ste. Marie canal in Ontario, designed to give access to Lake Superior by avoiding the rapids on the St. Mary’s River. All was going well until war broke out in 1812, and in 1814 American forces crossed the border and destroyed the lock. It was finally replaced in 1895, but on a different scale. The new lock was 274m by 18m, with the first gates to be operated electrically anywhere in the world.

Falls and rapids had been bypassed by portage throughout the early years of Canadian history, but there was no greater obstacle than that which faced anyone moving goods between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie: the Niagara Falls. The idea of a canal across the narrow strip of land between the two lakes only appeared indirectly. It had first been suggested in 1799 but nothing was done, but in 1816 a young man called William Hamilton Merritt appeared on the scene. He was actually born in Westchester County, New York in 1793, but his father had fought for the Loyalists in the War of Independence and, like many other Loyalists, moved north of the border after the war. Merritt bought an old saw mill on Twelve Mile Creek and later added a grain mill. He had problems with water supply, and conceived the idea of building a canal from the Welland River. He and some neighbours surveyed the route using a water level, basically the same instrument as that used by the Romans to build their aqueducts. They found a ridge in the way, which they calculated as 10m high; it is actually 20m. In 1818 Merrit put in a petition for the canal to the mill, but also added that it would now allow boats to pass the Niagara escarpment. Things moved forward, but as a result of the different surveys, a new line was proposed in 1824, this time descending to a point below the Falls at what became known as Merritton, now part of St. Catharine’s. There were more alterations even after work started in 1824. The canal largely followed natural waterways, but at one section a major artificial canal had to be dug for 3km. It was known as the Deep Cut and earned the name as it was up to 20m deep in places. Stabilising such a deep excavation was problematical and on 9 November 1818 after a period of heavy rain, when work was almost completed, the cutting collapsed, burying several workers. The original plan of using the Welland as a feeder was abandoned, and a new channel was cut to the Grand River. The canal opened in 1829, with access to Lake Erie down the feeder. This proved inadequate and in 1831 a new final section was completed. Like the Sault Ste. Marie, the Welland was developed over the years as ships got bigger. The current version is actually the fourth Welland Canal and was completed in the twentieth century.

The largest canal scheme of the period had little to do with commerce initially, but was a response to the war with America. Even after peace was agreed in 1814, it was clear to the British that if the Americans had advanced to the St. Lawrence, they could have cut off a vital transport link. The military needed to get supplies and men to the border quickly and efficiently, and the best way would be via a canal linking the St. Lawrence to the Great Lakes. The Commission set up to investigate the idea added, almost as an afterthought, that it would benefit agriculture and commerce. They saw a great trade developing in timber being brought to Montreal, and suggested, optimistically, ‘the result of this work, uniting the great waters of the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa, and offering a safe internal navigation, will turn a large portion of the present trade of New York towards Canada.’ The plan was approved for what would become known as the Rideau Canal, but nothing was actually done.

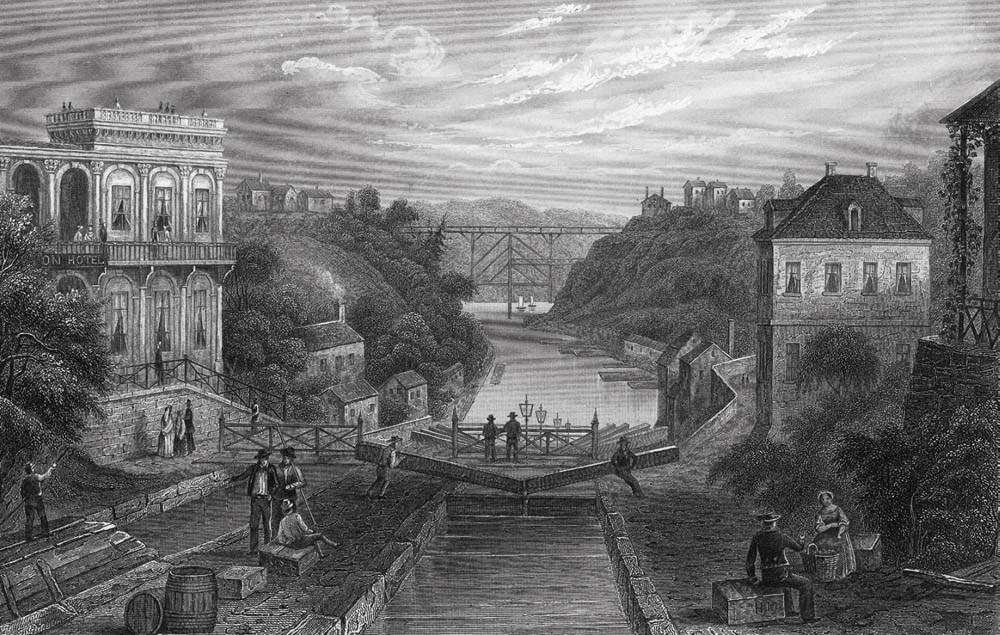

The Rideau Canal was Canada’s first major canal, the building of which was controlled by officers from the Royal Engineers. One of these officers was Colonel Henry Francis Ainslie who, as he travelled round the workings, kept a sketch book, with watercolour illustrations. This and the next two illustrations are from that book. This one shows the start of the canal at the Ottawa River, where it rises steeply through a flight of eight locks. It looks a lonely spot, but today it has been engulfed by the modern city and the Parliament Buildings stand next to the waterway. (Archives of Ontario)

As relations with the US improved, enthusiasm for the canal waned, but was rekindled when the renowned Duke of Wellington declared it essential. Lieutenant Colonel John Bey of the Royal Engineers arrived from Britain to take charge. His vision turned the original plans for a modest barge canal into something grander, with locks 133ft by 36ft. The survey was carried out by the military under Bey. It was to run from the mouth of the Rideau River, at what is now Ottawa, through a series of small lakes to the Cataraqui River that joined Lake Ontario at Kingston. The 204km route was a mixture of natural waterways with artificial canal and included the construction of forty-seven locks as well as dams and weirs on the river sections.

Although the work was supervised by officers of the Royal Engineers overseen by Bey, the actual construction was let out to small contractors. However, two companies of the Royal Sappers and Marines, each consisting of eighty-one men, were brought from England and their work included both guard duty and, when necessary, construction work. Many of the men stayed on after the work was completed and settled along the line of the canal. It was never going to be easy, building through what was, in effect, mainly an uninhabited wilderness; many of the contractors finished up bankrupt. The workforce was made up of local French Canadians and large numbers of Irish immigrants. The conditions were much like those on the Erie Canal, and the results were just as dire. Many men died of ‘swamp fever’. Bey decided that work should go on through the winter, when the workers would not be struck down by malaria. He also pointed out that although breaking through frozen ground would be difficult, the supplies could be brought in more cheaply: it is easier loading stuff onto sledges than putting it on carts that had to travel across unsurfaced roads. Because of the transport difficulties as much as possible had to be carried out on the spot: quarries were opened to provide the stone for locks, trees felled for housing and blacksmiths made the ironwork. Work went well and the canal opened by 1832. Nearly two decades after peace had been declared, the canal still had a military air: lock houses were fortified and blockhouses were erected for troops who would never need to use them.

This view, looking down from Barrack Hill, shows a lock and a bridge that is a reminder of the military role in building the canal – Sappers’ Bridge. (Archives of Ontario)

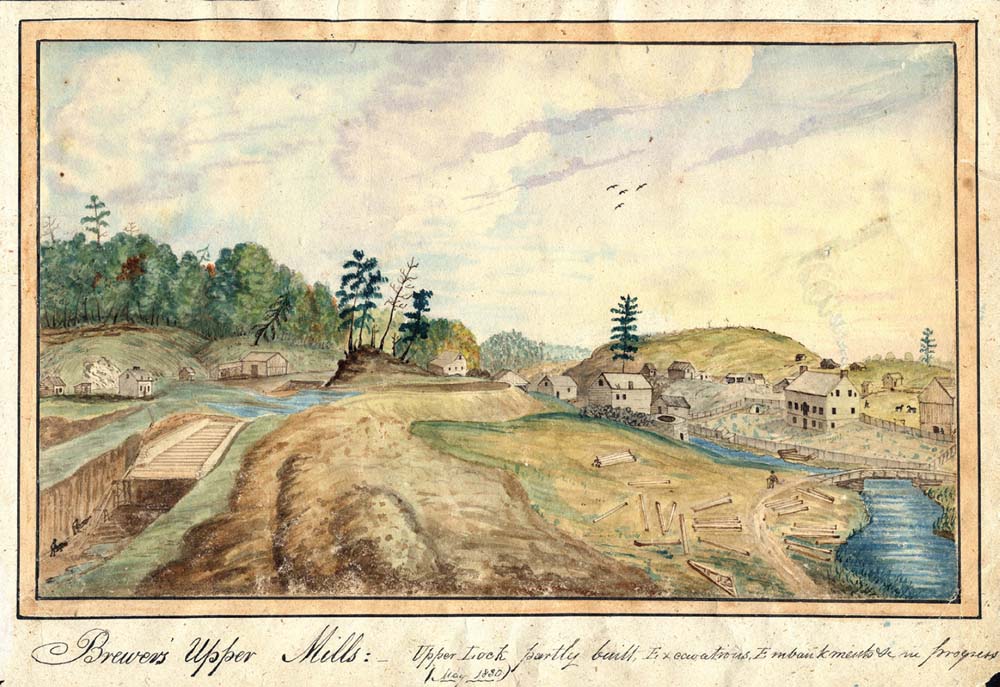

This is one of the few early sketches by Ainslie that shows construction actually still in progress. The site was described as Brewer’s Upper Mills and a half completed lock. A figure can just be made out with a wheelbarrow at the bottom of the lock chamber. (Archives of Ontario)

One of the greatest problems was the lack of experienced workmen. In his story of the canal, Rideau Waterway (1972), Robert Legget quotes John MacTaggart, who had come over from Britain to take on the job of Clerk of Works, He described what happened when Irish immigrants were brought to the workings:

‘ Even in their spade and pickaxe business, the [men] receive dreadful accidents; as excavating in a wilderness is quite a different thing from doing that kind of thing in a cleared country. Thus they have to pool in as the tactics of the art go – that is, to dig beneath the rots of trees, which not infrequently fall down and smother them.’

Some men left, tempted by better wages, for the stone quarries, work with which they were totally unfamiliar. The results were inevitable:

‘ Of course, many of them were blasted to pieces by their own shots, others killed by stones falling on them. I have seen heads, arms, and legs, blown in all directions, and it is vain for overseers to warn them of their danger, for they will pay no attention.’

The Rideau Canal in modern Ottawa. In summer it is used by pleasure boats, and in winter it becomes a popular elongated skating rink. (Tony Webster)

The Rideau Canal was initially successful as it offered a far better transport system to the Great Lakes than travelling down the St. Lawrence, which was still largely unimproved and famous for its hazardous rapids. But in the 1840s, work started on improving the St. Lawrence and the glory days of the Rideau ended. It might have gone the way of so many other canals in North America, but the country through which it passed still had few decent roads. It remained in business long enough to be appreciated as a tourist attraction and is now a popular route for holiday boaters.

Rivers had always been vital in opening up North America to European settlers, and canals were just as important in linking the various systems. They were vital for trade in goods and for moving people around the country. They also introduced innovations, some of which we will look at next.