Early on in the canal age, the Duke of Bridgewater remarked that his canals would ‘do well enough if they can keep clear of those damn’d tramways’. Not many agreed with him. The tramways were seen as vital links between industrial sites and waterways, feeding cargo down to the boats. One of the many tramways in South Wales came into being, not so much from the necessity to bring cargo to the canal, but to settle a troublesome dispute. The Glamorganshire Canal was promoted by the iron masters of Merthyr Tydfil to link to the docks in Cardiff. The major shareholder was William Crawshay of the Cyfarthfa ironworks. For a time all went well, but this canal had forty-nine locks in just 24 miles of waterway and as trade grew so did congestion. Crawshay began demanding that, as the main promoter, his craft should be given precedence. Samuel Homfray of the rival Penydarren ironworks had a radical solution. The original Act had allowed for ‘collateral cuts or railways’ to be built. Homfray decided to circumvent the worst bottleneck on the canal by building a 9½-mile tramway from his works to the canal at Abercynon. It was a conventional tramway, with cast-iron rails set on stone blocks and was worked by horses. It was built on a gentle 1 in 145 gradient, so that horses only hauled the full trucks downhill and had the return journey with empty wagons. It would have remained no more than a footnote to canal history but for events in February 1804.

The start of the new century had seen the end of James Watt’s patent and with it his monopoly of steam engine development. Other engineers took up the chance to make new, bold experiments. One of these was the Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick. He experimented with high-pressure steam. He realised that he could dispense with the condenser, only losing the effect of atmospheric pressure, just under 15psi. The high-pressure engine could thus be made small enough to be moved around. His first experiments were portable engines that could be hauled by horses to where they were needed. But by 1801 he had built a portable engine that could drive itself along – a locomotive. His first experimental model huffed and puffed its way up Camborne Hill in Cornwall on Christmas Eve of that year, accompanied by a cheering crowd, many of whom climbed on board for the ride. It was destroyed in an accident a few days later. But Trevithick went on to design a steam-powered stagecoach that was demonstrated on the streets of London. It was not greeted with enthusiasm, and was very difficult to steer. The mechanism was simply a tiller attached to a single front wheel. That problem was about to be solved; steam locomotives would run on rails.

Homfray had heard of Trevithick’s experiments and suggested that he build a new version to run on his tramway to take over from the horses. The engine was to be dual-purpose. Not only was it expected to run on the tracks, but it also had to work as a stationary engine, powering machinery at the ironworks. In one respect, the trials were a great success. Trevithick wrote to a friend that ‘It worked very well and ran up hill and down with great ease, and very manageable, we have plenty of steam and power.’ Unfortunately the engine proved too heavy for the brittle cast-iron rails, several of which were smashed. A second Trevithick engine sent up to a coalfield in North-East England suffered a similar fate. The first experiments ended.

There matters rested until 1812, when the costs of the Napoleonic Wars sent the price of fodder for horses soaring. Now it was the owners of the Middleton Colliery near Leeds who were looking to reduce the costs of getting their coal to the Aire & Calder Canal. They were aware of the breaking rails and looked to use a locomotive that would be light enough not to cause damage but with sufficient power to do the work. The solution was a rack and pinion railway, in which a cog on the engine engaged with a toothed rack laid along one side of the conventional rails. The system worked, and attracted considerable attention, particularly from the colliery owners of Northumberland and Durham. This was the world’s first successful, commercial railway and other colliery lines soon followed, but advances in technology made it possible to dispense with the cumbersome rack and pinion. That system would later be revived for mountain railways. This phase of railway history culminated in the opening of the Stockton & Darlington railway in 1825. This has been hailed as an important step towards the modern rail system as it was the first line approved by an Act of Parliament that specified the use of steam locomotives. In its essentials, it was still a colliery line, writ large. Locomotives were only used in taking coal from the various mines to the River Tees. Passengers were carried, but at first they had to make do with a conventional stagecoach pulled by horses, but fitted with flanged wheels to run on the rails.

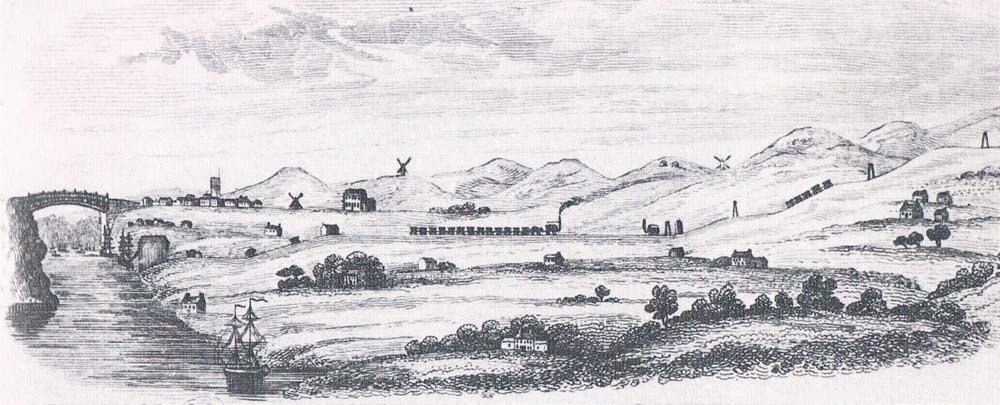

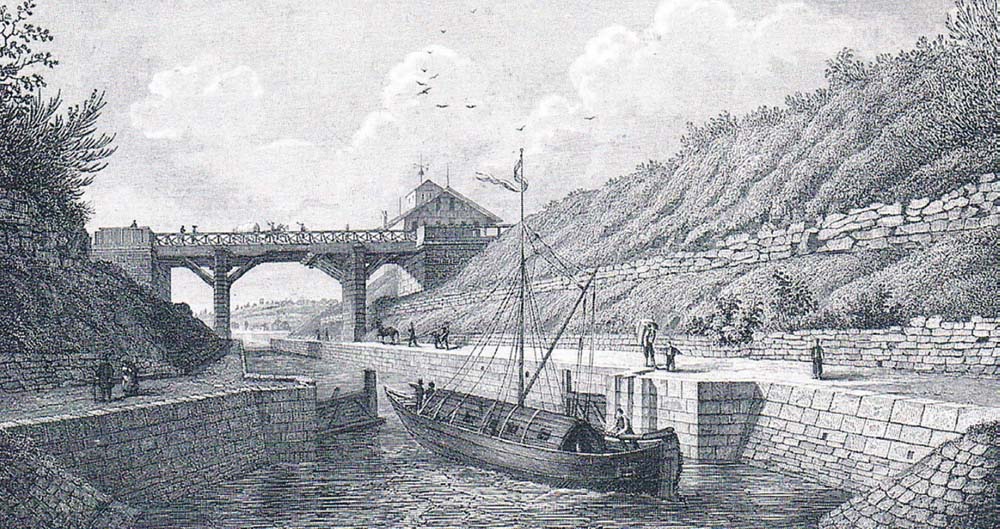

The earliest railways were all designed to take coal from collieries to the nearest navigable river or canal and were little different from the earlier tramways, apart from their use of steam locomotives. The illustration shows a section of the Hetton Colliery Railway, opened in 1822. One locomotive is seen hauling a line of trucks down to Staithes on the River Wear. A second engine can be seen at the foot of an incline, used to move trucks up and down the hillside by means of a stationary steam engine; the hill itself is somewhat exaggerated. At this date, many simply regarded railways as being useful means of feeding navigable waterways. (Anthony Burton)

Up to this point the canal authorities were sanguine about the developments. Thomas Telford argued that railway development was valuable in doing exactly what the tramways had done – bringing goods to canals. He still believed that nothing could improve on water transport for efficiency. If locomotives had never developed beyond the slow, clanking, often unreliable machines of the early days, then he would have been right. But that was never going to be the case: progress was inevitable, and the whole railway scene was transformed in the 1830s with the promotion of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

This was a different proposition, directly challenging existing routes, including the pioneering Bridgewater Canal. The situation had more than a touch of irony. Back in the 1760s, the Duke of Bridgewater had met fierce opposition from the established river navigations when he applied for his Act of Parliament, as they claimed they faced ruin if he went ahead. Now it was the turn of the Duke’s successors to make a similar claim – that permitting the railway to be built would spell financial disaster to the canals. And just as the Duke had argued that his canal was for the general good and should not be stopped by narrow financial interests and won his case, so now the railway company won a similar argument after a long battle. The canal companies hired the very best lawyers and George Stephenson, the chief engineer, was mercilessly grilled. It became apparent that the initial surveys had been rushed and every flaw was highlighted. The Bill was thrown out and had to be presented all over again – after work had been redone, checked and double-checked. This time the Act was passed.

The Liverpool & Manchester was no mere colliery line, but it took a competition to prove that it could be worked for both goods and passenger traffic using steam locomotives. The winning engine was the famous Rocket designed by Robert Stephenson. It was an inter-city line, offering travel at such previously unimaginable speeds as 30mph. And just as the success of the Bridgewater had brought a flurry of Canal Acts in its wake, so now too there was a rush to build main line railways across Britain. Canals were no longer the latest things in the transport world. And, in time, the railway network would spread, first to Europe, then America and eventually across the world. And wherever they appeared the old canal companies had to fight back or capitulate.

One obvious way to compete was to reduce costs. But boats were limited in size by the locks through which they had to pass. Attempts to replace horses by steam power had not proved successful. That only left one area where savings could be made – the cost of the boat crews. Up to now, in Britain, the work of most boatmen had been little different from that of, for example, a carter. They left home, went to their boats and returned home at the end of a journey. Now, however, the boating community were transformed into watery nomads. Instead of living in conventional houses, they would all have to live on board. On the main network of narrow canals, this would mean everyone squeezing into a cabin in the stern. This was necessarily no wider than the width of the boat, about 7ft, and only slightly longer. Fitting everything into such a space was a masterpiece of design. The cabin contained a range used for both heating and cooking and a cupboard for stores. The latter had a door that folded down alongside a bench to create a double bed. It would have been a spartan living space if the boat families had not made it bright and cheerful. Brasses were always highly polished, and the boatwomen were famous for their crochet work, producing lace curtains, matched by spotless lace-edged plates. It was probably in this period that canal narrow boats developed their traditional decoration of painted roses and castles. They may have given up their homes on land, but at least they could take grand homes and flourishing gardens around with them, even if they were only painted.

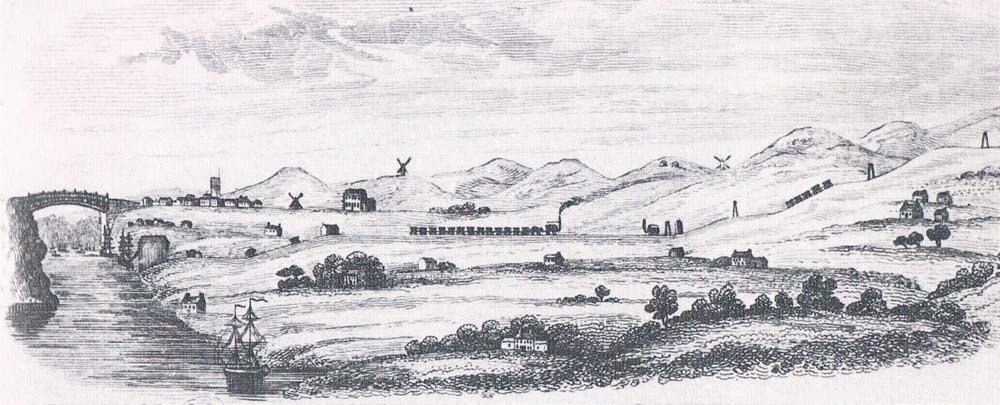

The first really modern railway, carrying both freight and passengers, hauled by steam locomotives, was the Liverpool & Manchester. In this picture it can be seen crossing the Sankey Navigation, which in its time had been an innovative canal, built before the Bridgewater. Competition proved too much for the Sankey, which became derelict, and anyone visiting the site today would find the viaduct still in use, but the canal little more than a depression in the ground. (Anthony Burton)

As railways developed they claimed many canal victims. This milepost is one of the few remains now seen of the Oakham Canal. Begun with great enthusiasm in the 1790s, it singularly failed to show a profit and it was with great relief rather than regret that the company sold the whole concern to the Midland Railway. The railway company promptly closed it as it obstructed plans for their rapidly developing system.

The facilities on the boats were strictly limited. Every boat carried its decorated buckie can in which to collect fresh water for drinking and cooking, but washing relied on water from the canal. E. Temple Thurston, in his classic 1911 account of a canal trip on a narrow point, asked the accompanying boatman about the toilet arrangements: ‘Why, look you, sur – that hedge which runs along by every tow-path. If Nature couldn’t grow enough leaves on that hedge to hide a sparrow’s nest, it ain’t no good to God, man nor beast.’

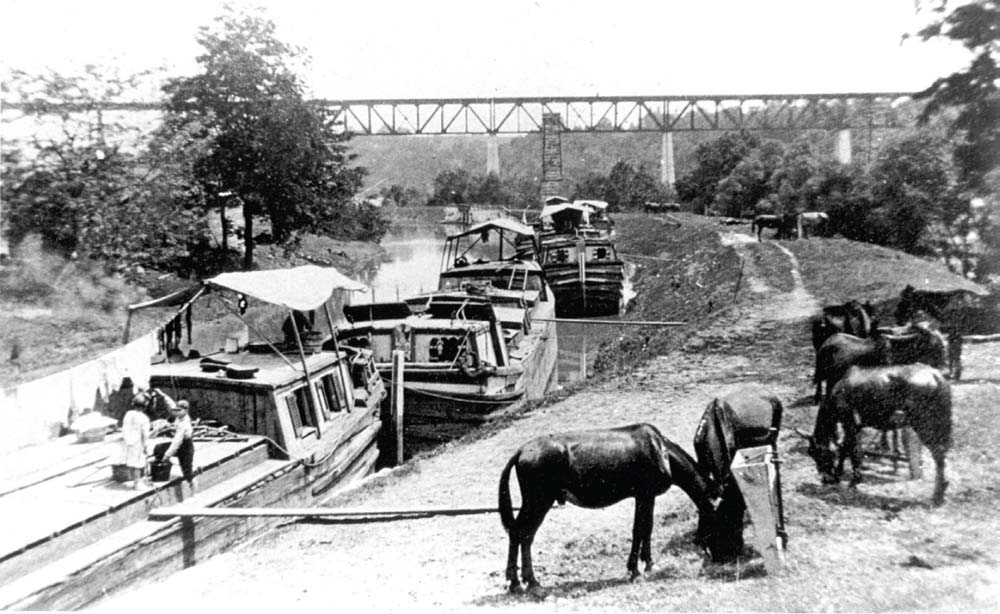

There were two advantages to moving on board the boat. The most obvious was that families no longer needed to rent a house on land. The second was that the boatman now had a crew who didn’t ask for wages. Everyone was expected to do their bit, even the children. They learned to lead the horse along the towpath from an early age. Nellie Cartwright began her boating life in the first years of the twentieth century and she told her story to actors from the Mikron Theatre Company, who were researching a show about boat people. She remembered one incident, when the family took the boat through Braunston tunnel on the Grand Junction one early morning. She was taking the horse in the pitch dark to rejoin the rest of the family as they legged through. She was cold and frightened, but the horse kept muzzling her: ‘I thought to myself, “He’s telling me not to be afraid,” and when I got to the end of the tunnel, I was as brave as brave.’ It was a hard life. As a grown woman she regularly loaded and unloaded up to 30 tonnes of cargo by hand, but she never objected. Her happiest memories were of the peaceful journeys, with the quiet, plodding horse. It is a life few of us can imagine, of unremitting hard work and an almost total lack of essential comforts, yet in her own words, ‘I would do it again exactly the same as I had it with the horses, the boats, the loading.’

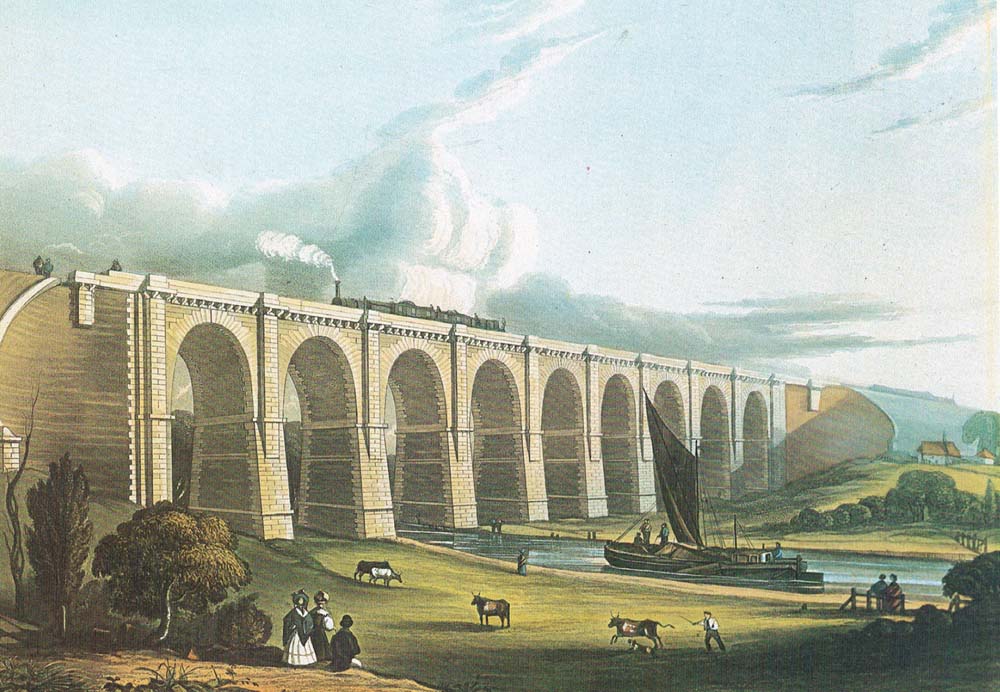

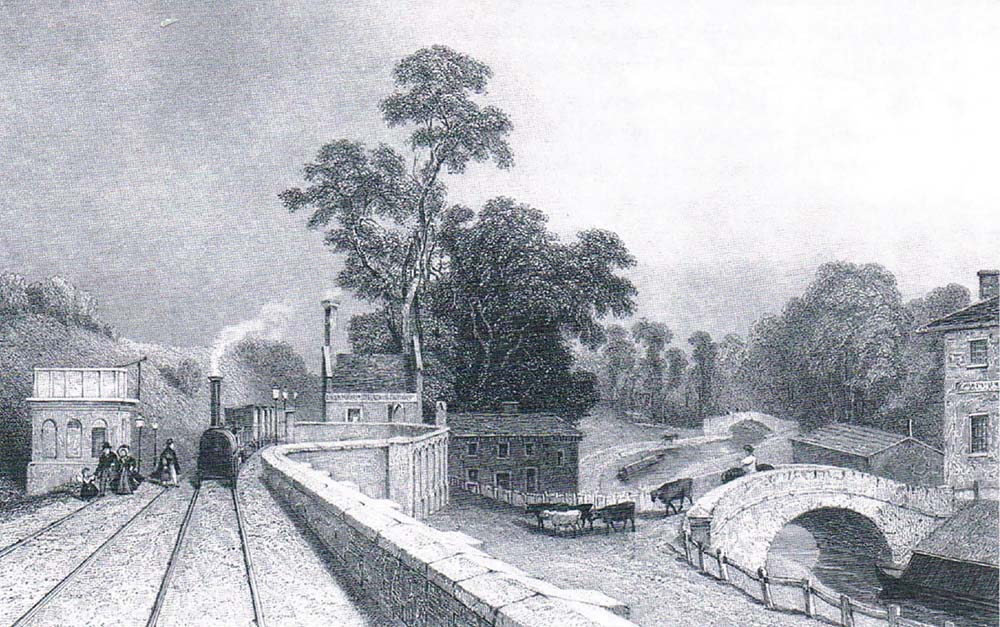

It was often easy to make a comparison between the new railways and the older canals. When Robert Stephenson surveyed the line for a railway to connect London to Birmingham, he selected a route very close to that chosen by Jessop for the Grand Junction Canal. The illustration must have been made very early in the history of the line as it appears to show the train hauled by one of the early Planet Class locomotives. (Anthony Burton)

Little more could be done in the short term to help the narrow boat community compete with the railways. Their greatest problem was the size of the boats and the loads that could be carried: what had seemed more than adequate in the 1760s, when the only competition came from packhorses or lumbering carts staggering down poorly surfaced roads, looked less appealing in the middle of the nineteenth century. The situation was not quite the same on the broad canals. The Aire & Calder Company had shown a rare willingness to move with the times. The waterway had an even longer history than that of the Brindley era canals, work having started as far back as 1699. In the early nineteenth century, what was in effect a new canal was built from the Aire at Knottingley, just outside Castleford, to a new port on the Ouse at Goole. The engineer in charge was John Rennie, and the canal opened in 1826, just six years after the passing of the Act. Until the arrival of the canal, Goole was just a hamlet of scattered houses. Now it grew into a considerable town. In 1828 the Company issued a statement to the press extolling the magnificence of the new port. It was now, they declared, ‘placed on a footing of equality with those of London, Dublin and Liverpool, and of superiority to all others in the United Kingdom, warehouses of special security being to be found in none other.’ They referred to the provision of secure, bonded warehouses, still a rarity at that time. Visitors to modern day Goole will find it difficult to reconcile what they find with this enthusiastic description. The notice also added another advantage found at Goole: ‘A steam towing boat, called the Britannia of 50 horse power, is provided to facilitate the navigation of the Rivers Humber and Ouse.’

The arrival of railway competition in Britain resulted in boatmen having to abandon houses on the land and live with their families on the boats. Whole families were able to squeeze into the back cabin of a narrow boat, including children such as these. At least by the time the picture was taken, motor boats had been introduced, so there were two cabins: one in the motor and the other on this, the unpowered boat, the butty. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

The Aire & Calder continued under the leadership of their chief engineer, William Bartholomew, who oversaw improvements in the navigation and also introduced a new type of water transport. In 1863 he designed compartment boats, which were little more than oblong boxes that could be joined together in chains of up to fifteen vessels, for haulage by a steam tug. The first vessel in the line was fitted with dummy bows to make the train more manageable. Their similarity to pudding tins earned them the name ‘Tom Puddings’, a name that stuck as long as they remained in use. They were designed to bring coal from the Yorkshire collieries to Goole. At the port, the individual Tom Puddings were brought under massive hoists, where they were lifted to the top of the tower, upended and the coal poured down chutes to the holds of waiting ships.

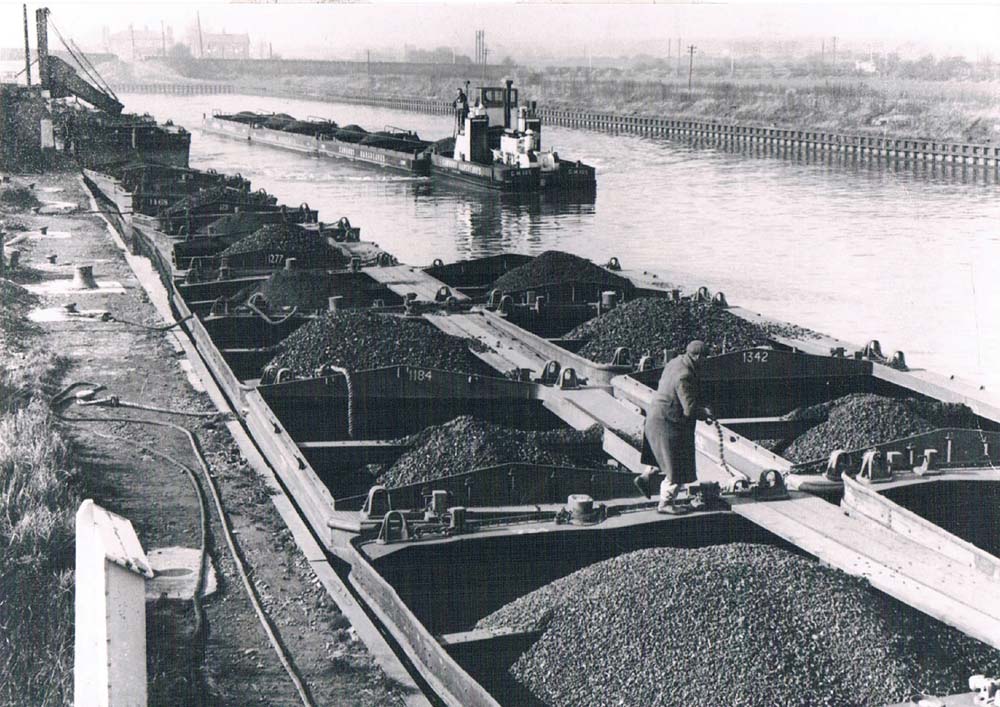

To compete with the railways, canals were modernised in many different ways. On the Aire & Calder Navigation this included a new type of vessel, known as a ‘Tom Pudding’. Looking, as the name suggests, like outsize pudding tins, these could be linked and towed by a tug. Here they are seen being loaded with coal at a colliery site, from where they would be taken to the port of Goole for transhipment. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

The system was so effective that it remained in use well into the second half of the twentieth century. The author saw the system in operation during a trip on the Aire & Calder in the 1970s and waited while they came down the lock. The train was clearly too long to fit into the lock. The hawsers that held the train to the tug were pulled in and the tug passed into the lock, taking the first seven containers with it. That left another eight apparently stranded and tugless. The answer was simple. The lock was refilled and then, with the top gates opened, the bottom paddles were raised. The flow of water was strong enough to suck in the rest of the containers. It was thanks to this programme of constant improvement that the Aire & Calder survived railway competition for so long. Other waterways were less fortunate.

At Goole the Tom Puddings were unloaded by being floated under a hoist, lifted to the top and upended, allowing the coal to flow down a chute into a waiting ship. Although no longer in use, this hoist has been preserved as an important industrial monument. (Anthony Burton)

Many of the canals built during the mania years had struggled to make a profit even before the railways came along. The Oakham Canal is a classic example. For the shareholders, however, the railways were a boon. The canal lay right in the path required by the Midland Railway, which simply bought it up, closed it down and built on top of it. For the first time the investors actually got money back after half a century of losses. Other canals were bought up, but kept open. The Great Western Railway, for example, bought several canals, including the Kennet & Avon. In several places, the lines of rails and waterway lie close together, and the railway company was not in favour of too much competition. They were required by an Act of Parliament to keep the canal open, but that didn’t mean they had to encourage its use. They took their cue from the poet Arthur Hugh Clough and his advice to doctors:

‘Thou shalt not kill; but need’st not strive

Officiously to keep alive.’

Another inevitable result of the coming of the railways was that investors lost interest in canals. They were now seen as out of date, and investors poured their money into the new transport system. Across the Atlantic, canal companies put up a spirited fight – even though it was a canal company that tried to introduce railways in the first place.

The first commercial experiments with steam locomotives in America began on the portage section of the Hudson & Delaware Canal as it crossed the hills. As no one in America had any experience of designing and building locomotives, the company sent their engineer, Horatio Allen, to England. He brought back four engines, one of which designed by John Urpeth Rastrick at his works at Stourbridge had an embossed lion’s head on the end of the boiler, earning it the name Stourbridge Lion. This locomotive was tested, and Allen manned the footplate for the first run in August 1829. On his own admission he had ‘never run a locomotive nor any other engine before’. But, he added, ‘If there is any danger in this ride, it is not necessary that more than one should be subjected to it.’ The section chosen for the trial began with a straight section of about 200 yards, then crossing a trestle bridge over the Lackawaxen Creek, before heading off on a curved track into the woods.

‘ The locomotive having no train behind it answered at once to the movement of the valve; soon the straight line was run over, the curve (and trestle) was reached and passed before there was time to think … and soon I was out of sight in the three miles’ ride in the woods of Pennsylvania.’

What Allen didn’t realise as he bowled cheerfully along was that the spectators had seen the wooden bridge sway alarmingly as he crossed it and that the heavy engine was leaving mangled and twisted rails in its wake. The experiment was a failure; the lion had roared its last and was dumped in a shed where it was left to rot. It was inevitable, however, that as both engines and tracks improved, a railway system would be developed in America and challenge the canals and waterways for their trade.

The first real competition was felt by the Erie Canal as railways encroached on their territory. First on the scene was the Mohawk & Hudson Company, which laid lines between Albion and Schenectady. The first locomotive to work the line was the rather ungainly Dewitt Clinton. It was a mark of the growing confidence in American railroads that this was designed and built in America, not imported from Britain. It must have been galling to the canal company that the designer, John Bloomfield Jervis, was originally engineer to the Delaware & Hudson Canal. Old allegiances were already being broken. It made its first run in 1834, proceeding at a stately 15mph on the flat, but struggling with hills. Nevertheless, it was sufficiently successful for other companies to follow. By 1847 there were ten independent railroads working along the same basic line of the Erie Canal. Had they co-operated, they might have posed more of a threat, but they were too busy competing to worry about boats. The different companies built their own termini and refused to pass on details of their schedules, so that although in theory it was possible to travel between Buffalo and Albany in about 14 hours, the wise traveller would allow at least a couple of days. Charles F. Carter described such a journey in his book When the Railroads were New. His account tells of delays, including a wait at Syracuse that lasted all day, during which time no one dared leave the train in case it left without them. In the event it took 38½ hours to cover the 290 miles – an average speed of just over 7mph, which must have made a leisurely trip on a canal packet appealing.

Freight traffic was not hugely affected at first, largely because the canal offered lower rates. But in spite of the teething difficulties of the railroad companies, the canal companies took the threat to their revenues seriously and waged a propaganda war, portraying it as a threat to life and limb. Inevitably, just as in Britain, investors moved money away from canal construction and into railroad building. And, again, it was the smaller canals that suffered first: five of the lesser canals in New York State succumbed quickly, and the Delaware & Hudson bowed to the inevitable and rebranded itself the Delaware & Hudson Railroad. The Erie fared better than most, but the development of the New York Central Railroad in 1853, which united the old mix of lines in a single company, proved a formidable rival. Eventually the Erie went the way of all the other American canals as traffic dwindled and closure became inevitable.

Railways spread rapidly through mainland Europe in the 1830s, although they reached some parts surprisingly late: Spain didn’t get a line until 1848, and Portugal, Sweden and Norway had to wait until the 1850s. Russia, however, was among the early pioneers. The immediate effects were not so dramatic as they had been in Britain, where investors had almost instantly favoured the new system. In France, Marc Seguin had designed a locomotive to work the Lyon & St. Etienne Railway, which had previously used horses, as early as 1828, and new lines were soon being built, intended from the first for steam locomotives. Yet French enthusiasm for canals had not diminished, largely because they were built on far more generous lines than the narrow canals that dominated the British scene. Even as new railways were being planned and built, important canal projects were also getting under way.

American canals also suffered from railway competition, as is dramatically illustrated by this photograph. It shows barges below Lock 38 on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. There has obviously been either a breach or a severe drought and they are unable to move. In the background is the imposing trestle railway viaduct over which trains can run unimpeded. (Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Society)

The Canal du Midi had been a great success, but as a route from the Mediterranean the canalised section only extended as far as Toulouse where it joined the Garonne. The river was difficult to navigate, prone to dropping levels in summer and flooding in winter. In 1838 a new canal to bypass the problem area was authorised. The Canal Lateral à la Garonne was begun in 1839 and completed in 1856. It was a massive undertaking, running for 194km from Toulouse to enter the tidal river at Casters-en-Dorthe. It was built on an impressive scale, with fifty-three locks, able to take vessels 30m long and 5.5m wide. There are two imposing aqueducts: over the Tarn, near Moissac, and across the Garonne at Agen. The latter is the more impressive, 539m long and carried on twenty-three masonry arches. Recently the canal has been improved, with locks being increased in size to take 240 tonne barges. There was a bottleneck at the locks at Montech, and it was decided to bypass them by a novel device, a water slope, built in 1874. A boat approaching the slope to make the trip downhill floats up against a watertight gate, situated a little way down the slope. Once the boat is in position, the gate is moved by two locomotives, one on each side of the slope. As it travels down, the wedge of water with the boat floating in it is also carried down to the bottom of the slope. When that is reached, the gate is lifted and the boat can carry on with its journey. For an uphill journey, the boat floats up to the slope, and the gate closes behind it.

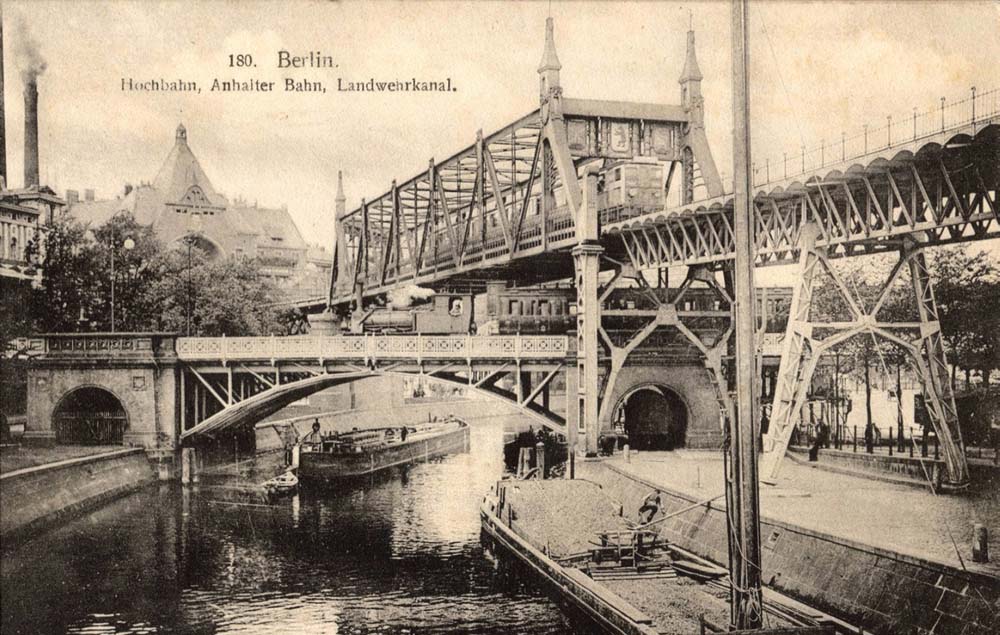

In Germany, canal construction continued into the railway age. The Landwehr Canal was built in 1845, forming, with the River Spree, a loop around Berlin. When it came to building the section of the city’s underground railway system – the S-Bahn that ran above ground – it was found convenient to build it over the line of the old canal. This section has changed little over the years, but the line seen carrying a steam locomotive no longer exists.

Even more ambitious was the building of the Canal de la Marne au Rhin, which became France’s longest canal at 310km, with 171 locks and a number of tunnels, including the 4,877m Mauvages and the 2,307m Arzviller. It proved a very important waterway and a commercial success, linking Strasbourg to the busy industrial regions of Alsace Lorraine. It also demonstrated the French view that both railways and canal were important in an integrated transport system. Work on building the canal began in 1846 and at the same time construction got under way on a railway on the same route, the two often running side by side.

Germany also continued building canals into the railway age. Berlin doubled in size during the first half of the nineteenth century, as the capital of Prussia, and such rapid growth needed better transport, which was initially met by a new canal network. The city sits on either bank of the River Spree. In 1845 work started on the Landwehr canal that bypassed part of the river and allowed barges to bring vital supplies, especially coal to the developing society and its new industries. It is only 10.5km long, with just two locks, but it had a large port at the centre in what is now the district of Kreutzberg. Where most canals show a certain uniformity in the bridges that cross them, the canal has an enormous variety in every material from brick to iron. Although commercial traffic is scant, it has a booming tourist trade: passengers can enjoy the sites of Berlin by taking the round trip by river and canal. It was the start of a period of development that lasted into the 1870s, linking Berlin to the River Oder. Ironically the canal also proved useful later, when Berlin needed a new urban transport system. These were the underground U-Bahn and above ground S-Bahn. It was difficult fitting rails into an already crowded city without demolishing expensive property. But the canal already cut a swathe through the buildings, so it made sense to run overhead lines directly above the waterway.

Today the Landwehr Canal has become busy with tourist boats, and among the attractions are the many ornate bridges along the way, including this one in Kreutzberg, near the canal basin. (Anthony Burton)

Ludwig I of Bavaria, not to be confused with the ‘mad king’ Ludwig II, was very progressive. He encouraged the development of modern industries and transport. During his reign, the country got its first steam railway, worked initially by a locomotive provided by the Robert Stephenson works in Newcastle, Der Adler (The Eagle). The engine is a rare survivor of the early days of European railways. Even before that date he had planned for a waterway that would connect the Main and the Danube. The survey of the line was begun in 1828 and completed in 1832, which seems long, but this was to be a 172km long waterway, with a summit level 110m above the point where it joined the Regnitz, a tributary of the Main. This involved 100 locks, as well as extensive earthworks. Construction began in 1836 and at one time there were some 6,000 men at work. The only mechanical aid was a steam shovel that was used in a deep cutting near Dörlbach. Designed to take 100 tonne barges, it prospered from its opening in 1845 and was soon recording tonnages of almost 200,000 tonnes a year. Inevitably it suffered from railway competition and, with a summit over 450m above sea level, had frequent problems with water shortages. It continued in use for just over a century, by which time work had already begun on an alternative waterway along a similar route. The Rhine-Main-Danube Canal took even longer to complete than the Ludwig: begun in 1921, it finally opened throughout in 1992. Further north in Sweden, there was one notable addition to the watery system, joining Lake Vänern to the Norwegian border. Completed in 1868, it arrived only twelve years after the country’s first railway.

The 1840s also saw the construction of the very ambitious 172km long Ludwig’s Canal in Germany. Considerable engineering works were needed, including the deep cutting at Dörlbach shown here, with locks able to take 100 tonne barges.

Railways were also late arriving in Asia: India only got its first line in 1853, but the nineteenth century did see major advances in water transport. There may have been no rush towards steam railways, but the Raj showed a greater enthusiasm for steam on the water. The first paddle steamer was built at Lucknow in 1819 by William Trickett, although the actual engine had to be brought over from the Butterley ironworks in England. By 1834 the powerful East India Company had begun regular services on the Ganges between Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Allahabad. It was a curious service. The side-paddle steamers also carried sail, but were strictly limited to cargo: passengers were housed in a flat-bottomed vessel towed along behind. One hopes it was comfortable as the whole journey could take up to four weeks. The most important company founded in the early days was the India General Steam Navigation Company, established in 1844. Fifteen years later they had a fleet of ten steamers.

India had an extensive system of irrigation canals, dating back to the Mughal period. Over the years, many had fallen into disrepair. One of these was the Doab Canal that ran for 140 miles from the Jumna River in the foothills of the Himalayas. The job of rebuilding it was given to army officers Captain Robert Smith and a 23-year-old artillery officer, Proby Cautley. The work was completed in 1830 when Smith left, leaving Cautley in charge of the works. By 1831 he had been appointed superintendent of canals for the North-Western Provinces. Five years later, he conceived a far grander project – an irrigation canal that would leave the Ganges above Hardwar, and after Nanu would split into two branches, one returning to the Ganges, the other joining the Jumna. This was construction on a vast scale, with the main lines originally planned as running for 255 miles with 73 miles of branches: this was later extended even further and, when completed, the main was 348 miles long. He spent six months going over the ground in 1840, but could only get agreement for its construction with the proviso that it should also be a navigable canal. Work began on the Ganges Canal in 1843, under Cautley’s direction.

His first task was to persuade the local Hindu priests to approve the scheme. At first they were bitterly opposed to a dam that would imprison the holy waters of the Ganges, but Cautley appeased them by leaving a gap through which water could flow downstream. He also promised to repair several of the ghats where the pious came to bathe in the river and, at the opening ceremony, prayers were offered up to Lord Ganesh, the god of good beginnings.

Cautley’s biggest problem was getting the raw materials he needed, especially bricks. These all had to be made by hand, and he was soon employing contractors with a workforce of nearly a thousand brick moulders and several hundred more to transport the bricks. His attempts to modernise production met fierce opposition: his brickmaking machines were attacked and the men went on strike. The problem was eventually sorted, but the project depended on manual labour. Apart from building dams and digging the channel, at Roorkee, the canal had to be carried over the Ganges on a quarter-mile long aqueduct. The work was eventually completed in 1854.

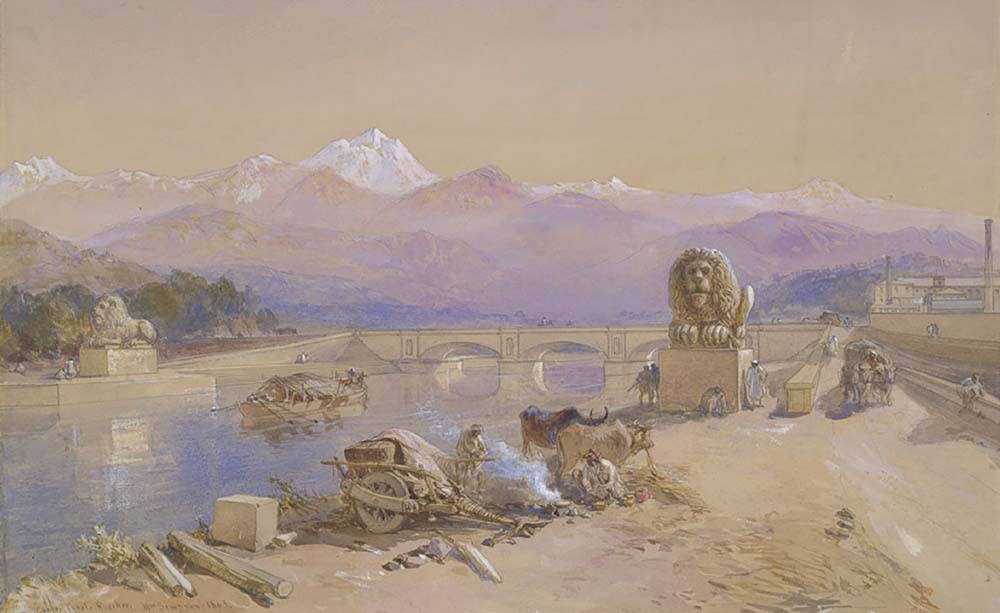

Irrigation canals were common in India in the nineteenth century, but the Ganges Canal was a grand undertaking that was designed for navigation as well as water supply. The painting shows the head of the canal near Haridwar in northern India, close to the border with China. It was painted in 1860, just four years after the canal opened.

The grand opening ceremony saw the sluices opened by the Lieutenant-Governor to the accompaniment of a gun salute and the national anthem. Cautley was allowed to retire from the service and when the vessel on which he travelled to join his ship for England passed Fort William, he was given a thirteen-gun salute in honour of his achievement. He received more formal recognition that year, with a knighthood and elevation to the honorary rank of Colonel. When in 1858, the government of India passed to the crown, Cautley was appointed to the fifteen-strong council that ruled under the secretary of state.

The Ganges Canal was not the only navigable canal in India, but it was by far the most significant. Not only did it provide a valuable transport route, but it also succeeded in its prime objective to supply water to 1,500 villages. There was one other long-term effect. Cautley was acutely aware of the lack of engineering expertise in the country, and helped to set up a College of Civil Engineering at Roorkee. It also showed that canals still had value in the railway age.