The three empires presented in this book presided over one of the most religiously diverse stretches of land on Earth. The adherents of the three Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), Hinduism, and a host of antinomian and heterodox groups within those religions, encountered various degrees of support, toleration, or persecution from the political establishments. The sources selected for this chapter reveal some of the main issues facing non-Muslim communities in these three empires.

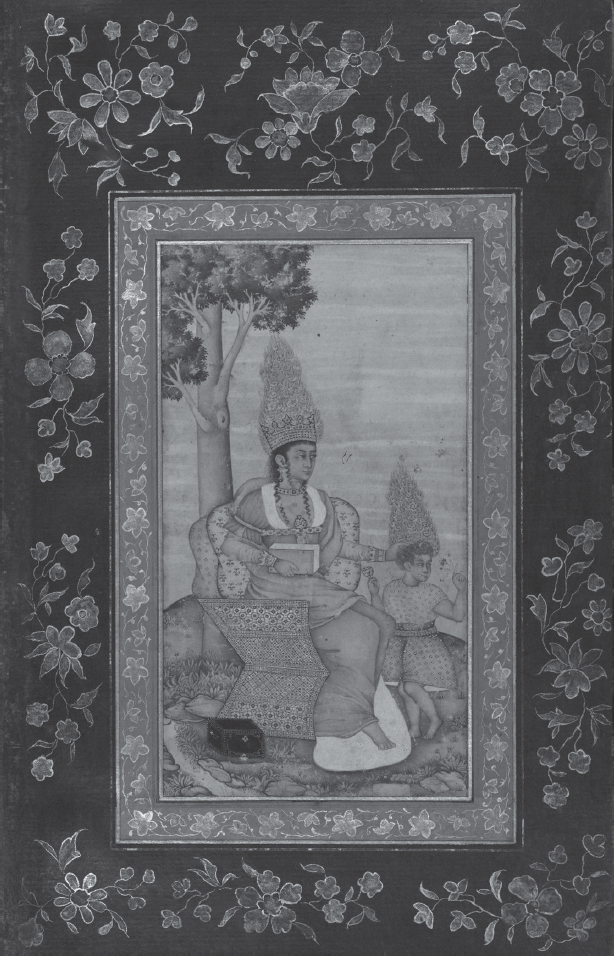

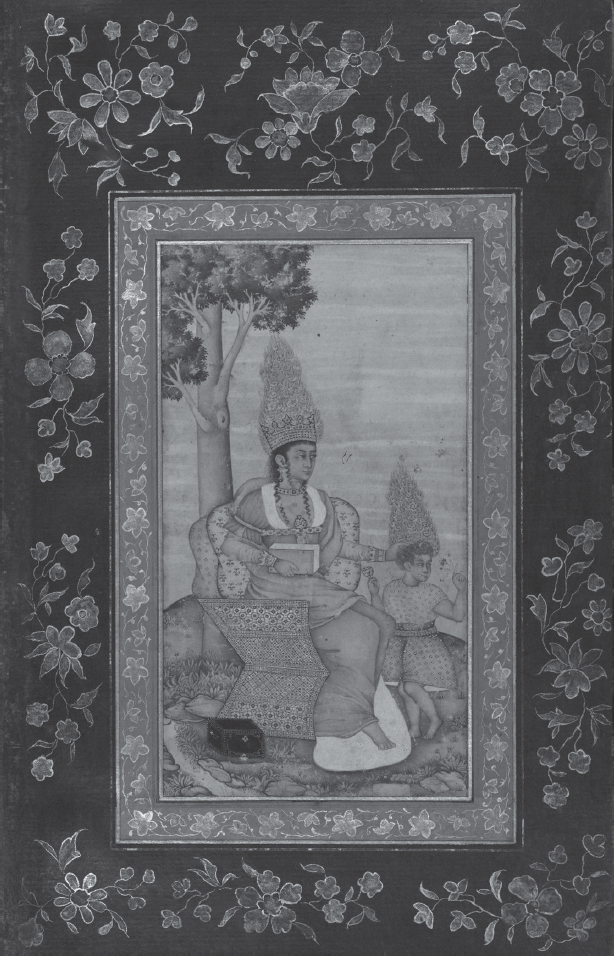

FIGURE 1.1 Mary and Jesus

The image is part of an album (muraqqaʿ) of Persian and Indian calligraphy and paintings, probably compiled in the nineteenth century. The album holds thirty-four illustrations, featuring works of miniaturists such as Abu al-Hasan, Manuhar, Dawlat, and Sadiqi. It includes portraits of rulers and the elite, as well as illustrations from older manuscripts such as Saʿdi’s Gulistan. Samples of the works of renowned calligraphers such as ʿImad al-Hasani, ʿAli Riza ʿAbbasi, Mir ʿAli, and ʿAbd al-Rashid al-Daylami that bear their signature add to the luster of this album.

Source: Album of Persian and Indian calligraphy and paintings. Walters Ms. W.668, fol. W.668.10b.

Date: Late sixteenth century–nineteenth century

Place of origin: Iran and India

Credit: Walters Art Museum

Conversion was a heated issue that occupied religious and political authorities of the time. Although most Muslim jurists agreed that forced conversion is not permitted in Islam, the fatwas (religious authoritative rulings) that follow reveal that when everyday sociopolitical concerns of religious minorities met imperial objectives of expansion and domination, the permissibility of conversion became a matter of the legal opinion of jurists in the imperial service. This was further complicated given the legal status granted to dhimmis (people of the book; that is, Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians, but not Hindus) living under Muslim rule. Through examination of fatwas in the Ottoman domain issued by the highest religious authorities from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, in the second essay Nikolay Antov demonstrates how leading jurists’ legal interpretations related to state policies regarding the Christian populations of Eastern Europe were maintained over the long term and consistently contributed to jurisprudential rigidity and an emerging legal conformism. Fatwas regulating the sociopolitical and economic activities of non-Muslim communities are a great source to investigate to learn how religious minorities attempted to negotiate their legal protection, expand their rights, and avoid persecution.

In the broader framework of imperial politics, conversion can be viewed as a societal issue, but it was also a very personal experience for those involved. The fear of persecution or exclusion from socioeconomic opportunities was a common reality for many members of minority communities. Those who converted did not experience immediate relief but rather felt great anxiety caused by a crisis of faith, doubt as to the true path to salvation in the afterlife, and ostracism by family and friends. In the first essay, Rudi Matthee explores the personal dimension of conversion through examination of a rare autobiographical account left behind by ʿAli Akbar, an Armenian Christian merchant of Isfahan (the Safavid Empire’s seventeenth-century capital) who converted to Shiʿi Islam. This extraordinary source offers us a window into the tormented mental world of a man who abandoned one faith and adopted another.

In contrast to the Ottoman Empire, which was in constant warfare with Christian powers, the Safavids and the Mughals tolerated the presence of Jesuit missionaries, with the latter ruling over a vast population of Hindu subjects. In fact, at times Mughal emperors such as Akbar and Jahangir and the Safavid Shah ʿAbbas exhibited a degree of religious tolerance rare for the era by any measure. Although the state’s lenient policies regarding religious minorities oscillated from time to time and necessitated original political solutions, disputations in matters of creed between Christian and Muslim theologians mirrored the contestations of the earlier centuries in central Islamic lands. Such issues as the perceived polytheistic nature of the Trinity and challenging the authorship of the Bible and the accuracy of the Gospels (and contrasting it to the superiority of the Qurʾan as an unaltered word of God) were evoked by the ʿulamaʾ to elevate the imperial religion over all others.

In the final essay of the chapter, Corinne Lefèvre examines and translates a debate that took place in the intimate audience hall of the Mughal emperor Jahangir between the Jesuit Jerónimo Xavier and the Muslim jurist ʿAbd al-Sattar, who later compiled them in the collection Majalis-i Jahangiri. Jahangir, following in the footsteps of his father Akbar, was keenly interested in all matters of faith, and even the abrogation of the Qurʾan was not off limits in these nightly debates. Muslim-Christian disputations at the Mughal court were highly polemical and had the benefit of centuries of doctrinal scaffolding, but when it came to Hinduism, a great degree of inquisitiveness and interest dominated the discourse, which is revealed in Emperor Jahangir’s conversation with a Brahman translated in this essay. Audrey Truschke’s essay in chapter 3 further demonstrates this inquisitiveness by exploring Jahangir’s debate with a Jain monk in which the emperor questions the merits of the monk’s ascetic practices.