ARTHUR F. BUEHLER

Of all Sufis of the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent, Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1624) is the most well-known in the Islamic world due to his Collected Letters, 536 letters intricately detailing Sufi practice and its relationship to shariʿat (divine law).1 Through these letters Sirhindi redefined and expanded Sufi practice and notions of shariʿat to such an extent that he was called the “renewer of the second millennium.”

Under the tutelage of Baqibillah (d. 1603 in Delhi), Sirhindi finally had his own breakthroughs in contemplative experience that changed his life. He experienced the (apparent) ontological unity of being that his father ʿAbdulahad had taught him from books. Baqibillah made sure that Sirhindi went beyond this stage as soon as possible.2 From there, Sirhindi was able to experience both multiplicity and unity and could discern between them. What had changed in the interim between these experiences was that he had become an incredibly transformed human being. With this realization, Sirhindi noted that large numbers of Sufis were interpreting their unity-of-being experience as an experience of God. Sirhindi had conclusively confirmed through experience what his mentor had told him, namely, that they were merely experiencing the shadows of the attributes of God. Even more distressing was their increasing disregard for the injunctions of the divine law. Sirhindi went from being a bright, freshly certified Sufi teacher to a man with a mission.

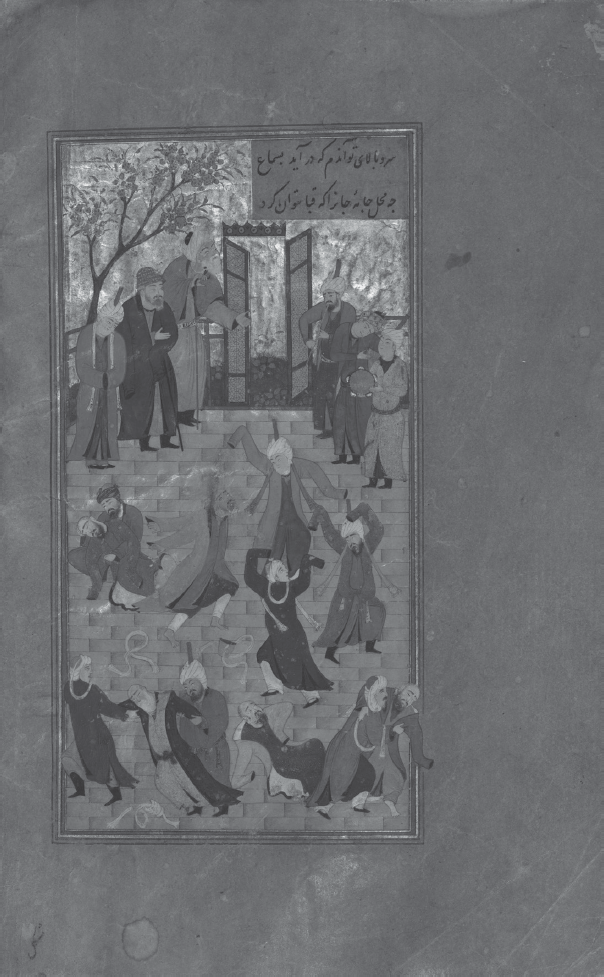

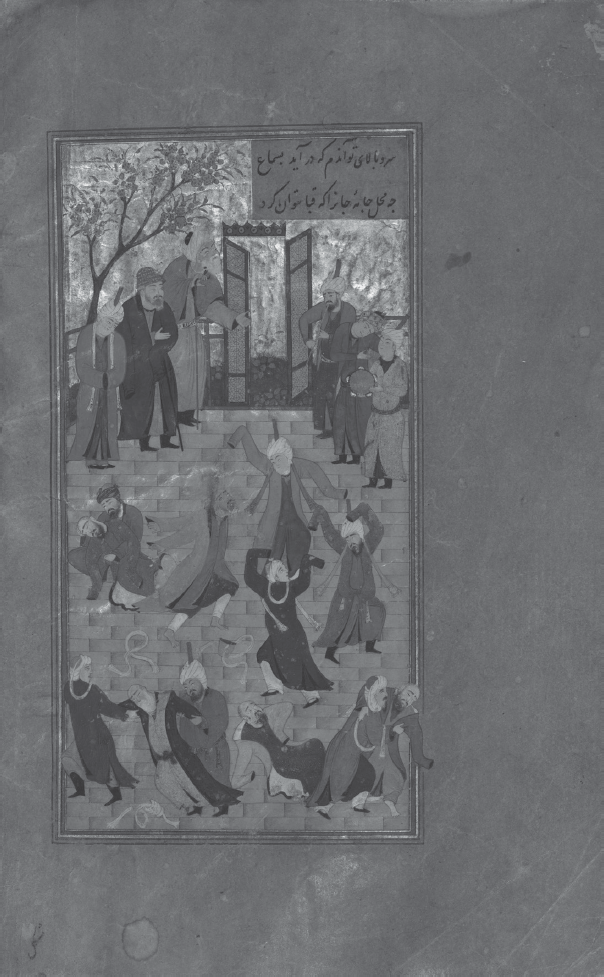

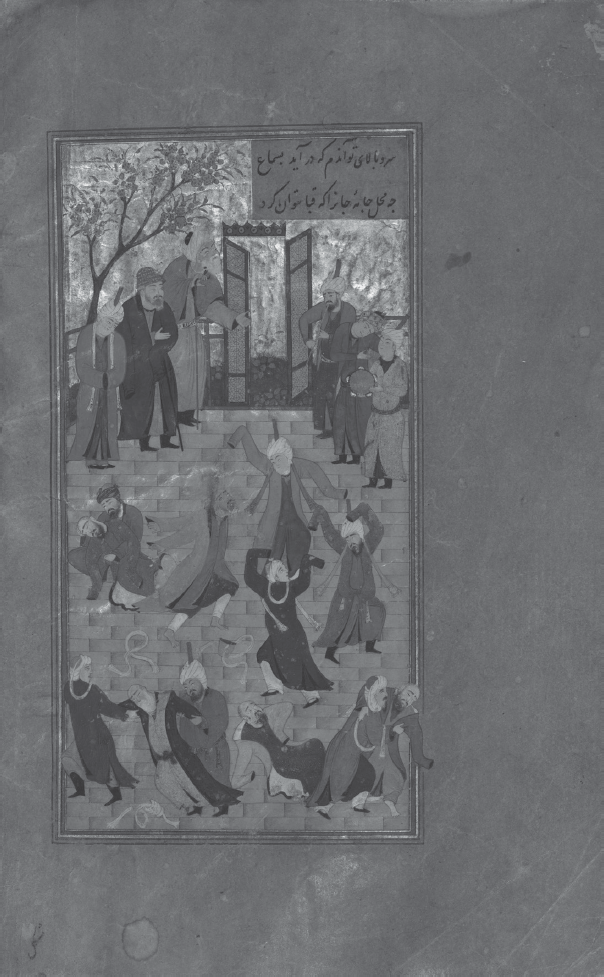

FIGURE 3.2 Sufis in devotional ceremonial dance known as samaʿ

This illustration from a copy of Hafi’z Divan depicts Sufis engrossed in samaʿ that some religious scholars found controversial. It was scribed by the famed calligrapher Zayn al-ʿAbidin ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Jami in 1512 in Safavid Iran.

Source: “Divan-i Hafiz,” collection of poems (divan). Walters Ms. W.628, fol. 49B

Author: Hafiz (1315–1390); Zayn al-ʿAbidin ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Jami (scribe)

Date: 1512

Place of origin: Iran

Credit: Walters Art Museum

More than any other Naqshbandi Sufi after Baha’uddin, Sirhindi was the pivotal figure who redefined Sufism’s role in society and who elaborated Mujaddidi mystical exercises. His title, “the renewer of the second millennium” (mujaddid-i alf-i thani), makes him a cofounder figure for the later Naqshbandiyya and reflects the significance of his influence. He was so convincing in his stress on following the prophetic example and on shariʿat as the basis for postrational experience that almost all Naqshbandi Sufis worldwide became Mujaddidis by the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Of all the Indo-Muslim leaders of the seventeenth century, Sirhindi was one of the most prolific. Much material in his seven epistles and collection of 536 letters expresses a deliberate scheme to define the spiritual boundaries of the Indian Muslim community. Unlike other Sufi practices, which were culture-specific or geographically rooted in the subcontinent, Sirhindi’s letters could be disseminated in their original Persian or translated and transmitted throughout the non-Persianate Islamic world. Such a “book” made Mujaddidi practices and teachings both persuasive and accessible to educated Muslims anywhere. Some consider the separate nation-state of Pakistan as the twentieth-century manifestation of a conception of an Islamic orthodoxy and community significantly influenced by Sirhindi’s teachings.3

THE COLLECTED LETTERS OF AHMAD SIRHINDI: AN OVERVIEW

Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi began writing letters to his spiritual guide Baqibillah in 1599. In 1616, Muhammad Jadid Badakhshi Talaqani, one of Sirhindi’s disciples, compiled the first volume of these letters. There are 313 letters in the first volume with the chronogram title, The Pearl of Inner Knowledge (Durr al-ma’rifat). Sirhindi’s son, Muhammad Ma’sum, directed ʿAbdulhayy b. Khwaja Chakar Hisari to compile a second volume of 99 letters, corresponding to the number of the most beautiful names of God with the chronogram title, The Light of Creation (Nur al-khala’iq). This was published in 1619. The third volume of 114 letters was compiled by Muhammad Hashim Kishmi Burhanpuri in 1622, with the chronogram title, The Inner Knowledge of the Realities (Ma’rifat al-haqa’iq). Ahmad Sirhindi passed away before there were enough letters for a fourth volume, so the printed versions include another eight or ten letters.

The first complete lithographed edition of Collected Letters (Maktubat) was printed in Delhi in 1871, followed by seven, almost exact, reprints. Then Nur Ahmad (d. 1930) began to edit what has become the critical edition of Collected Letters. Born in the Sialkot district of what is now Pakistan, Nur Ahmad left for Mecca in 1881, becoming initiated by the famous Chishti-Sabiri master Shah Imdadullah (d. 1899). Returning to India in 1890, he was initiated by the Naqshbandi-Mujaddidi shaykh, Shah Abu’l-Khayr (d. 1924 in Delhi), and began to work on the critical edition of Collected Letters. Using teams of able students, he gathered all available manuscripts and over a period of three years, and these manuscripts were compared with the lithographed edition. Nur Ahmad went to Sirhind Sharif after all discrepancies were noted, and Ahmad Sirhindi’s family allowed him to compare his corrected copy with the manuscripts there. Then he began a massive editing project, isolating and identifying Qurʾan passages and hadith, translating and defining difficult Arabic and Persian words and phrases, supplying biographical and bibliographical information on well-known Sufis, jurists, and their writing, defending Sirhindi occasionally against his detractors, and adding a subject index for each letter at the beginning of each of the nine fascicles that were published between 1909 and 1916. This publication was printed on four different paper qualities, ranging in price from one rupee, four annas to two rupees, eight annas. Until a 2004 Iranian edition, just about all Collected Letters published in Persian after 1916 were facsimile versions of the original lithographed Nur Ahmad edition.

No other published Sufi treatise goes into such detailed explanations of Sufi practice and how to facilitate postrational experience and ego transformation. Nor has any other Sufi treatise been translated into so many other languages. Along with the Mathnawi of Jalaluddin Rumi, the Collected Letters has probably been the most widely disseminated Islamic text (but not the most read because of its extreme difficulty) after the Qurʾan.

LETTER 1.11: ONE OF SIRHINDI’S EARLY CONTEMPLATIVE EXPERIENCES

Letter 1.11 begins with Ahmad Sirhindi writing to his shaykh, Baqibillah (d. 1603),4 concerning his second experience of a station.5 Here we learn that passing through a station is not the same as being stabilized in a station. Naqshbandi-Mujaddidis ascending in their contemplative exercises (muraqabat) pass through the reflections of the stations of the prophets, but this is not the same as resting in those actual prophetic stations. Nor is passing through the stations of one’s spiritual superiors the same as resting there. This point is important, for some have accused Sirhindi of implying his superiority to the revered Abu Bakr as-Siddiq, the first successor to Muhammad.6 Indeed, it is this letter that ostensibly caused alarm with Jahangir, who accused Sirhindi of having “also written a number of idle tales to his disciples and believers and made them into a book which he called Collected Letters, (Maktubat), [which] drag (people) into infidelity and impurity.”7

In this letter, he described his experience of the station of annihilation of the ego-self in God with its respective attraction to God (jadhba), known as “wayfaring in God.” Trying to make sense out of what happened, Sirhindi decided that his experience was probably what Khwaja ʿUbaydullah Ahrar (d. 1490 in Samarqand) had experienced. It is this experience that moved him from the path of intentional, willful action to that of being in intimate spiritual companionship with Baqibillah. Throughout the Collected Letters Sirhindi discusses a station and the center of a station, where the movement is from the periphery of the station to the center. From the center, one typically moves to the periphery of the next station.

When going inside, Sirhindi described an abyss, the experiences of which resonate very much with what Christian contemplatives have called “the dark night.”8 This is a poignant reminder that inner wayfaring is not always a joyride. One of the experiences of the station of servanthood (maqam-i ʿabdiyat), the highest station of the stations of being near to God (maqamat-i walayat), is being yanked out of one’s separateness. This happens in such a way that one is confronted with one’s corporeal darkness and denseness as the subtle centers of the created world suddenly zoom very distant from the world of command.9 This is the place from which Sirhindi said that he was worse than a foreign infidel or an apostate heretic, someone who has denied God and who will not have the benefit of God’s mercy in the Hereafter.

Differentiating different levels of reality was a common theme for Sirhindi. One should not confuse the entity (ʿayn) and the traces of the entity (the attributes). Because Sirhindi is of the Muhammadi disposition (mashrab), he and Shaykh Abu Sa’id Abu’l Khayr (d. 1049 in Nishapur) have passed beyond contemplative witnessing (shuhud) of the attributes to contemplatively witness the qualities (shuyunat) of God.10 Sirhindi was able to verify his experience of the Essence by “comparing notes” with his predecessor, ʿUbaydullah Ahrar, and confirmed that experiencing an absolute annihilation in God depends on experiencing the disclosure of the Essence (tajalli-yi dhati) first.11 It was from this station that Sirhindi proceeded to further higher stations and was able to stabilize himself in the station of the disclosure of the Essence and experience “presence with God” (hudur ma’ Allah). One outcome of this experience was his losing interest in reading about others’ inner experiences and descriptions of the maps that guided such experiences. He was still very much in transition. Even with his inclination toward the ideas of Shaykh ʿAla’uddawla Simnani (d. 1336), Sirhindi wisely realized that he did not have enough experience to jump to conclusions about experiences of the unity-of-being.

Toward the end of the letter Sirhindi chose not to engage with Ibn al-’Arabi concerning their different perspectives. Instead he gave us a glimpse of a shaykh’s life and activities beyond spiritual guidance, for example, assisting disembodied spirits on their way and being spiritually and physically attacked.

The next section concerned the age-old difficulties shaykhs have with their disciples: laziness, self-sabotage, and other ego strategies to prevent them from progressing. Given the experiences he described in the first part of the letter, it appears that Sirhindi had only received conditional permission to teach. Baqibillah was still formally supervising Sirhindi’s teaching. After discussing his teaching experiences, there is some technical discussion that makes sense only to Mujaddidi specialists. The reader can recognize that seekers “travel” in the various subtle centers and that they are in various stages of ascent to God or descent to the material world.

Sirhindi often mentioned the attributes and Essence because the student often experienced the attributes as different from the Essence. How they experience the attributes/Essence is a litmus test for their progress and difficulties. The guiding Mujaddidi principle following Sunni-Maturidi creedal injunctions is that the attributes of God are neither the Essence nor other than the Essence.12 Thus, when students experienced the attributes/Essence in a manner described in this letter, they have made significant progress. Sirhindi ended the letter in the bewilderment of experiencing something beyond oneness, and beyond will and desire. These are annihilated as he engages in spiritual companionship (suhbat) with his completed and completion-bestowing shaykh.

Translation

LETTER 1.11

When the lowest of servants, Ahmad (Ahmad Sirhindi), was in a previously experienced station, in accordance with your noble instructions, he caught a glimpse of the first three caliphs. God almighty be pleased with them.13 They are [supposed to] appear in that station. I did not see them the first time because I was not stabilized in that station. I could only recognize Hasan, Husayn (the Prophet’s grandsons), and Zaynul’abidin (Husayn’s son) from the Prophet’s family. God almighty be pleased with all of them. However, I did experience the Prophet’s family passing through this station. By keen observation one can realize this.

At first I perceived that I did not have an affinity for this station. Lack of affinity or connection (munasabat) is of two kinds. [Temporary], that is, when no path appears and they show a path to him. Then there is a connection. [Second], Absolute, where there is no way to move. There are two paths that lead to this station, not three. That is, from the perspective of these two paths, another does not appear. The first path is seeing one’s shortcomings and faults. With a strong attraction to God, one focuses all intentions on good works. The second path is spiritual companionship (suhbat) with a completed shaykh who is attracted to God and who has finished wayfaring/contemplative practice (suluk). God almighty, by means of your (Baqibillah’s) favor, has blessed me with the first path to the extent of my ability.14 Bless God.

No good deeds are happening even though I concern myself with this. But there comes a time that I no longer give any importance [to good deeds] and become agitated. One knows that there are no deeds being performed that are worthy of the angel above the right shoulder to record.15 It is known that the book on the right has no good deeds written in it. Any writing is futile and useless. How could I be worthy of God almighty? Anything in the world is better than I, even a foreign infidel or apostate heretic. I can be considered worse than all of them.16

With respect to attraction to God, some requisites and related aspects of [attraction to God] remained although I had completed “wayfaring to God” (sayr ila Allah). This happened while experiencing annihilation of self in the center of the station of “wayfaring in God” (sayr fi’llah). All of this was complete. The states of annihilation of self occurred as I detailed to you in the last letter. It must be that this is the annihilation discussed by Khwaja ʿUbaydullah Ahrar when he said, “the end of this work.” It must be the same annihilation that is verified after the disclosure of the Essence and ascertaining the realization of “wayfaring in God.” The annihilation of intentionality is one aspect of this annihilation. As long as one is not annihilated in God, he will not be able to go to God’s Majestic Court.

Those who do not have an affinity for this station are in two groups. One group focuses on the station and searches for a way to arrive. The other group does not even turn toward the station. Turning toward Baqibillah, according to the second path [of having spiritual companionship with a completed shaykh attracted to God], is a more effective way to arrive at this station than other paths. The affinity and connection of this path is evident because it is established with Baqibillah. It is all about obedience to his command. Sometimes there is arrogance and boldness, otherwise, I am this very Ahmad, your ancient servant.

The second time I observed from this station, other stations appeared, one higher than the other. After focusing on begging and grief, I experienced the station above the first station. I realized that this station was that of ʿUthman b. ʿAffan (the third caliph, assas. 656),17 and that the other caliphs also had passed through this station. This station is one of completion (takmil) and guidance. There are two stations above this one that I will discuss now. Above [the station of completion and guidance] another station came into view. When I arrived at that station, I became aware that this was the station of ‘Umar Faruq (the second caliph, assas. 644) and that the other caliphs had also passed through [this station]. Above this, the station of Abu Bakr (the first caliph, d. 634) appeared. God almighty be pleased with all of them. I also experienced this station.18 In addition, I was with the shaykhs of Baha’uddin Naqshband in the stations they had experienced.19 The other caliphs (after Abu Bakr) also passed through this station. There is no superiority except [the difference] between passing through a station and being stabilized in a station. There is no station above that of Abu Bakr’s except the station of the Seal of the Messengers (Muhammad). God bless him completely and perfectly.

Another station of light came into view opposite Abu Bakr Siddiq’s station. God almighty be pleased with him. It was so exquisitely beautiful that nothing like this had appeared before. It was a bit higher than Abu Bakr’s station like the height of a bench above the ground. Abu Bakr’s station is the station of belovedness (mahbubiyat), variegated and colorful. I experienced the many colors reflected from this station. After this, in the same manner, I experienced a subtlety spread out on the horizon in all four directions like the sky or fragments of clouds. Baha’uddin Naqshband is in the station of Abu Bakr. God almighty be pleased with them both. I found myself in the station opposite to the station of Abu Bakr and experienced it in the same manner [with variegated colors and subtlety].

Another thing that happened was my giving up guiding others on the path because it was not satisfying. It felt like I had become drowned and lost in the abyss of the world. How can a person who finds the inner strength to come forth from this abyss be able to forgive oneself? No matter how many other things a person may have to do, it is necessary and agreeable to guide others. But guiding others is conditional upon asking forgiveness if troubling, evil doubts occur while guiding others. Then one requests God’s satisfaction. Without observing these conditions, satisfaction will not benefit the person, who will then remain at the bottom of the abyss. According to Baha’uddin Naqshband and ʿAla’uddin ʿAttar (d. 1400 in Hissar, Tajikistan), without observing these conditions one can guide others and have God’s satisfaction. God almighty bless their inner hearts. This lowly one, without observing these conditions, found that sometimes there was God’s satisfaction. Other times I was at the bottom of the abyss.

Another experience is in the book Fragrances of Intimacy (this is ʿAbdurrahman Jami’s Nafahat al-uns). Quoting Shaykh Abu Sa’id Abu’l Khayr (d. 1049 in Nishapur),20 “When the entity (ʿayn) does not remain where will the trace (the attribute) remain?”21 “It does not leave one alone or spare one”22 [Q. 74:28]. These words at first glance are difficult to understand. According to Shaykh Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi (d. 1240 in Damascus) and his followers, the entity (ʿayn) is a part of what is known about God almighty and it is impossible to have an extinction of the entity. From ignorance, knowledge changes. When the entity is not extinct, then the trace (associated with an attribute) does not go anywhere either. In this manner, it all makes sense to the mind.

Shaykh Abu Sa’id did not come up with a solution. After utterly concentrating [on this matter], God almighty revealed the secret of these words [to him]. He realized that neither the entity nor the trace remained. He found the meaning in himself, and there was no longer any problem. [For me], the station of this inner knowledge (ma’rifat) also came into view. A very high [station] indeed! It was above the station that Ibn ʿArabi and his followers had spoken about. These two experiences (Abu Sa’id’s and Ibn ʿArabi’s) do not contradict each other. One comes from one place and the other from another place. To explain in detail requires a long discussion.

[Another topic] concerns the lasting nature of this experience [of the flashing disclosure of Essence (tajalli-yi dhati-yi barqi)]. Abu Sa’id said that it also becomes pertinent [to ask] what the meaning of the experience is and what its lasting nature is.23 I found that this experience was lasting, although it rarely lasts.

Looking at books is another experience that is not at all gratifying except to describe what has happened to notables as they traverse the stations. It is commendable that one can read about this kind of thing. The states of former shaykhs are very interesting. [Theoretical] books about realities and experiential knowledge (ma’arif) cannot be comprehended [without actual experience]. This especially [applies to] talk about asserting the unity of being (tawhid-i wujudi), the ordered emanations (tanzilat-i muratib), and the subtle centers.24In this regard, I find a great affinity with Shaykh ʿAla’uddawla Simnani, and we are in harmony concerning this matter both in personal inclinations (dhawq) and in firsthand experience. However, I am not going to deny the aforementioned knowledge [of unity-of-being] and oppose [those who assert the truth of unity-of-being].

Another experience involved me fighting diseases a few times, which had effects. In the same way, the conditions of some deceased persons appeared from the liminal world (ʿalam-i barzakhat),25 and I alleviated their pain and distress. But now I have no more ability to concentrate on that or anything else. I had some misfortunes and ill treatment from people. There were many associated with me who were unjustly destroyed and forced to leave their homes. Basically no distress or affliction reached my heart, even where they had done harm.

Some companions who are in the station of attraction to God have talked about their inner knowledge and contemplative witnessing without having even made one step toward stations of the path. They do not have the slightest experience of the states of these way stations. It is hoped that God almighty will bless them with the good fortune of wayfaring after all the aspects of being attracted to God [are finished].

Shaykh Nur (from these aforementioned companions) is stuck in this station. He has not arrived at the upper point in the station of attraction to God. He finds difficulty both in action and in rest and does not understand the harm [to himself]. Automatically he is stopped in his tracks. Likewise, most of his companions, due to a lack of guidance in behaving beautifully (adab), have become stuck in their spiritual work. In this spiritual work it is surprising, from my point of view, how they get stuck when their intention is to develop themselves. It happens that they delay the spiritual work without intending to. Otherwise, the path is quite near. Shaykh Nur has gone to the lowest point. The activity of attraction to God has brought him to the end where he has arrived at the interface (barzakh) of that station. He was brought above, from the surface to the end [of the station] where the first attributes [appear] along with the constant light of the attributes. He sees himself separate from himself, and finds the shaykh to be annihilated. Then he sees the attributes separated from the Essence. Seeing that, he also arrives at the station of attraction to God. Now both he and the world are lost in a way that cannot be described in words. Whether outwardly in spiritual companionship or deeply hidden inside, one who is proceeding in [the level of isolation and absolute exclusive unity (ahadiyat-i sirfa)] will achieve nothing without bewilderment and confusion.

Sayyid Shah Husayn has also arrived near the end point in the station of attraction to God, and his arcane subtle center (sirr) has arrived at that point. Similarly, he sees the attributes separate from the Essence but he finds the Essence of the One (dhat-i ahad) everywhere. Outwardly he is happy and contented. Likewise, Miyan Ja’far has also arrived near the last point and appears to be very full of desire and lament, a lot like Shah Husayn. Among the other companions who have distinguished themselves are Miyan Shaykhi, Shaykh ‘Isa, and Shaykh Kamal who have arrived at the upper point in the station of attraction to God. Shaykh Kamal is proceeding in descent [to the world of creation]. Shaykh Naguri has come below the upper point even though he has a lot of distance yet to go. There are presently eight or nine companions right here who have come up from the bottom point. Some have arrived at the center point facing descent [to the world of creation]. Some of the others are near and others are far.

Shaykh Muzammil finds himself lost and sees the attributes [emanating] from the Origin (asl) and the Absolute everywhere. He perceives things in the world like mirages without specific features and finds nothing. Concerning the Mawlana whom we know, it appears that his permission to teach people is a really good idea, but it should be permission suitable to one attracted to God [that is, conditional permission]. There are some remaining matters, which he must benefit from because he has proceeded quickly without stopping. He will go to you (Baqibillah, lit. the Holy Presence), and you can tell him what you think will improve his situation. This poor one has reported whatever understanding has had. The judgment is yours. Khwaja Diya’uddin Muhammad was here a few days. Overall he found presence of God (hudur) and tranquility.26 In the end, due to a lack of income and not being at ease, he joined the army.

The son of Mawlana Sher Muhammad is also going into military service. Generally he is present with God and tranquil. He has not progressed due to some hindrances. He is quite arrogant. The servant must know his limits. After writing this letter, a feeling came over me and a state occurred that I couldn’t explain in writing. I verified the annihilation of will (iradat) and, just like before, the connection of the will became separated from desires. But the origin of the will remained like I have written before.

Now the will also appears from the origin. Neither desire nor will remain. As the form of this annihilation came into view, some knowledge appropriate to this station appeared. It was difficult to write this knowledge down because it was hidden and subtle. I should desist from writing about this knowledge. At the time of verifying this annihilation and overflowing knowledge, a special view beyond oneness (wahdat) appeared, although it is established that there is no view beyond oneness because there is not any affinity (nisbat). But I have reported what I have experienced. As long as I am not certain, I will not write boldly. The appearance of this station from beyond oneness is like seeing Agra beyond Delhi. There is no resemblance whatsoever. Whatever is in view is not oneness, nor beyond that, nor a station known by a title of reality, nor a truth known beyond that. Bewilderment and ignorance are the same. I do not feel any superiority from seeing this and do not know what to say. Everything seems to contradict everything else. Nothing comes for me to say. Surely this state resembles no other. God forgive me. I repent to God all that God dislikes—in speech, in deed, in thought, and in what is seen.

And also this time I have come to know that what I had thought to be annihilation of the attributes was in truth the annihilation of the characteristics of the attributes and their distinctions. [This happened] while the attributes became included in oneness and [other] characteristics became extinguished. Now the origin of the attributes has disappeared, as if one could be included in the other. Nothing remains of the predominance of exclusive unity. Nothing remains of any distinction from the level of comprehensive or detailed knowledge that I had realized. My entire vision has become focused on the outside world (bar kharaj). [According to the hadith], God was and with God there was nothing else.27 He is now as God always has been. This time my knowledge corresponds with my state. Before, I mentioned knowledge with this meaning but without experiencing the state. I hope that you will alert me to what is correct and what is in error. In addition, there is Mawlana Qasim ʿAli who has realized the station of completion as well as some companions here. God almighty knows best concerning the reality of my state.

LETTER 1.13: SIRHINDI’S FURTHER CONTEMPLATIVE DEVELOPMENT

In this letter, Ahmad Sirhindi was writing to his shaykh, Baqibillah.28 He explained to Baqibillah how he had ascended to annihilation in God and descended while abiding in God. Transformed by his experience, Sirhindi has returned to the material world. He has completed his journey in lesser intimacy with God (walayat-i sughra) in the shadows of God’s names and attributes. From the letter, it seems that he was still getting his bearings. Outwardly Sirhindi appeared to be an ordinary person, but inwardly his reality was extraordinary because inwardly he was with God. The five thousand year journey refers to the time it takes a non-Mujaddidi Sufi, through the exercise of the personal will, to purify the elements and the ego-self through daily spiritual exercises. As outlined in the previous letter, Sirhindi had annihilated all will and desire to follow the path of spiritual companionship with his completed/perfected shaykh—which is the fast track.

The phrases “All is God.” or “All is from God.” have become shorthand for experiencing the (ontological) unity-of-being (wahdat-i wujud) or contemplatively witnessing the unity of being (wahdat-i shuhud). When Sirhindi uses the term wahdat-i wujud, it is to designate the Sufi experience of wujudis who deny multiplicity in their assertion of the ontological unity-of-being. He proposes wahdat-i shuhud to balance this partial truth. Sirhindi experienced the unity-of-being as an elementary stage superseded by the experience of the attributes of creation being the shadow of God’s attributes.

This letter has Sirhindi declaring that there is no contradiction between the outer shariʿat (the Persian form of shariʿa) and his inner experiences. In the study of contemplative practice and religious experience, this is a significant move because it signifies that human-created-in-history shariʿat is the criterion to evaluate postrational, inner experience. For Sirhindi, an inner experience was ultimately valid only if it conformed to the creedal and orthopraxic Muslim Sunni Hanafi dictates of shariʿat. Such a stance was quite appropriate in an environment in which society is governed by the shariʿat, but in light of the apparently larger context of cross-cultural religious experience and consciousness studies, other issues are involved. If the way to God is endless, then it means that the shariʿat necessarily has to follow suit, for the infinite cannot be contained by the finite. Herein lies a much larger notion of shariʿat.

LETTER 1.13

The lowest of servants, Ahmad, exclaims one thousand and one ‘ahs’ of lament from realizing that the way to God is endless. Proceeding [along the way] has happened with such speed, with so many events, and with copious divine favor. Thus, the great shaykhs have declared that wayfaring to God (sayr ila Allah) is a journey of five thousand years. “The angels and the Spirit ascend to God in a day of fifty thousand years” [Q. 70:4]. This verse alludes to when I feel discouraged in spiritual work and my hopes are extinguished. The Qurʾanic verse, “It is God who sends down the saving rain after they have despaired and spreads out God’s mercy” [Q. 42:28] gives me hope.

It has been a few days since I have experienced wayfaring in the world as an ordinary person (lit., wayfaring in the things of the world, sayr fi’l-ashya’). Again, people wanting Sufi teaching have been flooding in, and generally I have begun teaching them. But still I do not find myself worthy of the station of completion to guide others. People’s insistence causes me not to say anything because of shyness and politeness.

Previously, I have repeatedly told you about how I was bogged down with the issue of asserting the unity-of-being (tawhid-i wujudi) along with actions and attributes being connected with the source (asl).29 When the truth of the matter became known, I emerged from being stuck. I experienced the adage “All is from God” prevailing. I saw more completeness in this than the saying, “All is God.” I knew God’s creation (af’al) and God’s attributes from a different perspective. Everything [was shown to me as it] passed above one by one, and my doubt completely disappeared. All that has been disclosed (kashifiyat) corresponds to the outer shariʿat without even the slightest contradiction. Sufis who contradict the outer shariʿat do so on the basis of what is disclosed to them, whether in sobriety or intoxication. There is no contradiction between the inner and the outer.

The contradictions that appear to those traversing the path need to be faced and resolved. The true realized one (muntahi-yi haqiqi) finds that inner experience corresponds to the outer shariʿat. The difference between the [superficial] jurists and the noble Sufis is that jurists know [topics of shariʿat] by rational proof and the Sufis know by their inner disclosures and by tasting. What is greater proof of Sufis’ sound condition than this correspondence (between their experience and the shariʿat)? “I will get upset and be quiet” [Q. 26:13] is how I feel now. I do not know what to say. I do not have the inclination to write about these states, nor is it possible to fit them in a letter. Perhaps there has been some wisdom in this. Please do not deprive this unfortunate one of your exceptional spiritual attention (tawajjuh) or leave me alone on the path. You were the starting point of these words. If there is verbosity, then you are the cause. It is better not to show any more arrogance. The servant should know his limits.

1. All references to Sirhindi’s Collected Letters are from Maktubat-i Imam-i Rabbani. 3 vols., ed. by Nur Ahmad (Karachi: Educational Press, 1972).

2. This is detailed in Arthur Buehler, Revealed Grace: The Juristic Sufism of Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624) (Louisville, KY: Fons Vitae, 2011), letter 1.290.

3. See “Ahmad Sirhindi: Nationalist Hero, Good Sufi, or Bad Sufi?,” in Sufism in South Asia, ed. by Clinton Bennett (London: Continuum, 2012), 141–62.

4. There are twenty letters addressed to Baqibillah in Collected Letters.

5. This experience is detailed in letter 1.7.

6. Sirhindi addresses these issues further in letters 1.220, 1.257, and 1.292, all of which are translated in Buehler, Revealed Grace.

7. Jahangir, Memoirs of Jahangir (Tuzuk-i Jahangiri), ed. Henry Beveridge, trans. Alexander Rogers (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1968), 2:93.

8. St. John of the Cross (d. 1591 in Segovia, Spain) refers to the “dark night” and is the eighth of ten stages in his schema of spiritual ascent. In transpersonal psychology, it refers to the relinquishment of a separate ego-self after many years of spiritual effort.

9. See Muhammad Sa’id Ahmad Mujaddidi, al-Bayyinat: Sharh-i Maktubat (Lahore: Tanzim al-Islam, 2002), 369. This is the best commentary on Collected Letters, but it only goes up to 1.29. The author comments on this subject further in his commentary at 331–33 using Mazhar Jan-i Janan’s letter mentioned below.

10. See Mujaddidi, al-Bayyinat, 385. This is discussed further in letter 1.287 found in Buehler, Revealed Grace.

11. The information given in Collected Letters and in the commentaries about the disclosure of the Essence, including the necessity of having a Muhammadan disposition, corresponds with the definition and explanation of the same term (al-tajalliyat al-dhatiya) given in ʿAbdurrazzaq Kashani’s Lata’if al-i’lam fi isharat ahl al-ilham, ed. Sa’id ʿAbdulfattah (Cairo: National Library Press, 1996), 309–10. In terms of Sirhindi’s experiences of abiding in God after the annihilation of the ego-self, such an experience characterizes the experience of an Essential disclosure of God. See Muhammad Dhawqi, Sirr-i dilbaran, 4th ed. (Karachi: Mashhur Offset Press, 1985), 115.

12. See Letter 2.67 in Buehler, Revealed Grace.

13. In this translation, parenthesis (indicate additional information) and brackets [indicate words not in the original text added for clarity].

14. The first path is Sirhindi’s situation during his first experience, which is outlined in letter 1.7; later on in the letter translated here (1.11) he goes on to thank his shaykh for being on the second path.

15. In the Islamic tradition, each person has an angel over the right shoulder recording one’s good deeds and another angel over the left shoulder recording one’s bad deeds.

16. A very detailed explanation of this experience is found in Mirza Jan-i Janan’s ninth letter in Ghulam ʿAli Dihlawi, Maqamat-i mahzari, Urdu trans. Iqbal Mujaddidi (Lahore: Zarin Art Press, 1983), 387–88. In short, Sirhindi was in such a place that when he looked inside himself all he could see was his “dark side” (lit., evil side, jihat-i sharr) in such a way that it appeared that he was absolutely devoid of any perfections or admirable qualities.

17. The text states “the one with the two lights,” referring to ‘Uthman’s two successive wives, Ruqiyya and Umm Kulthum, both of whom were daughters of the Prophet.

18. The interlinear text states that Sirhindi experienced the station by passing through it instead of being stabilized in this station.

19. Here the shaykhs refer to Baha’uddin’s teachers, not everyone in the lineage preceding him. In note eleven in Collected Letters 1.11.23 the editor states that Sirhindi was with these shaykhs as a son is with his father, as a seeker is with his spiritual master, or as a student is with his teacher.

20. This is ʿAbdurrahman Jami’s Nafahat al-uns.

21. See ʿAbdurrahman Jami, Nafahat al-uns, 308. The disappearance of the entity (ʿayn) is discussed in detail in letter 1.287 in Buehler, Revealed Grace.

22. The interlinear notes translate this Qurʾanic passage as “neither Essence nor attribute.”

23. It does not appear that Abu Sa’id discussed the disclosure of the essence in the Nafahat al-uns, although there are discussions of this subject by other shaykhs in ʿAbdurrahman Jami’s, Nafahat al-uns min hadarat al-quds, ed. Mahmud ʿAbidi (Tehran: Intisharat-i Ittila’at, 1992), 410, 555. Footnote 11 on 1.11.23 in Collected Letters adds the technical description of the experience in question, that is, a flashing disclosure of Essence. There is a further discussion of this type of experience in 1.21 and 1.27 in Collected Letters.

24. These are the subtle centers and entifications mentioned in the introduction to these two essays.

25. This barzakh is the in-between place between this world and the next, probably located in the world of the spirits, commonly called the world of command.

26. Technically hudur means being present with God in the station of oneness. Ordinarily it can mean “ease.”

27. This hadith is found in al-Bukhari, Bad’ al-khalq, 1, Tawhid, 22; and al-Nasa’i, al-Sunan al-kubra, # 11240. All specific hadith references in this chapter come from Mektubat-ı Rabbani, trans. into Turkish by Talha Hakan Alp, Omer Faruk Tokat, and Ahmet Hamdi Yıldırım (Istanbul: Semerkand Yayınları, 2004).

28. There are twenty letters addressed to Baqibillah in Collected Letters.

29. The text simply has tawhid, but the context and the interlinear note clearly indicate that tawhid-i wujudi is intended.

FURTHER READING

Buehler, Arthur F. Revealed Grace: The Juristic Sufism of Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624). Louisville, KY: Fons Vitae, 2011.

Friedmann, Yohanan. Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi: An Outline of His Thought and a Study of His Image in the Eyes of Posterity. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1971.

Haar, J. G. J. ter. Follower and Heir of the Prophet: Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624) as Mystic. Leiden: Het Oosters Instituut, 1992.