HÜSEYIN YILMAZ

A LOOK AT IDRIS-I BIDLISI’S CAREER

Idris b. Husameddin Ali (d. 1520) was born in Bitlis into a family of scholars. His father, Husameddin, was a renowned scholar and a bureaucrat in the service of the Aqquyunlu dynasty. He received a well-rounded education thanks to his father’s distinguished circle of friends, which included statesmen, scholars, poets, and Sufis. Among them was Abdurrahman Jami who seems to have had the greatest impact on Bidlisi’s thought. He joined the Aqquyunlu bureaucracy at a young age and soon became known to the Ottomans through diplomatic letters he composed for his patrons. Upon the Safavid takeover of Tabriz in 1501, he declined Shah Ismail’s (r. 1501–1524) offer to join his administration and instead took refuge with the Ottomans, where he was given a privileged position at Bayezid II’s (r. 1481–1512) court.

Later Ottoman tradition immortalized him for spectacular achievements as a statesman and a scholar. Following Selim I’s (r. 1512–1520) victorious military campaigns against the Safavids and the Mamluks, Bidlisi was commissioned with the difficult task of bringing independence-loving tribes, mostly Kurdish, under the Ottoman authority. He succeeded in doing so thanks to his scholarly credentials, diplomatic skills, and inherent knowledge of the area. He composed his Hasht Bihisht (Eight Gardens), a landmark in Ottoman historiography, upon Bayezid II’s request. Written in exquisitely ornate literary Persian, the work is reminiscent of Firdawsi’s (d. 1020) epic, Shahnama (The Book of Kings), which became increasingly popular in the post-Abbasid Mongol and Timurid courts. Being new to the world of the Ottomans, Bidlisi concerned himself less with a detailed and accurate chronicle of events than with using history to create a new imperial ideology based on the Sufistic conception of the caliphate. Unlike his near contemporary Aşıkpaşazade’s (d. 1484) Tevarih-i ʼAl-i ʽOsman, which emphasized the frontier characteristics of Ottoman polity and the saintly culture of antinomian Turcoman mystics, Bidlisi recast the Ottoman dynasty in the vocabulary of a mystical philosophy of high Islamic culture.

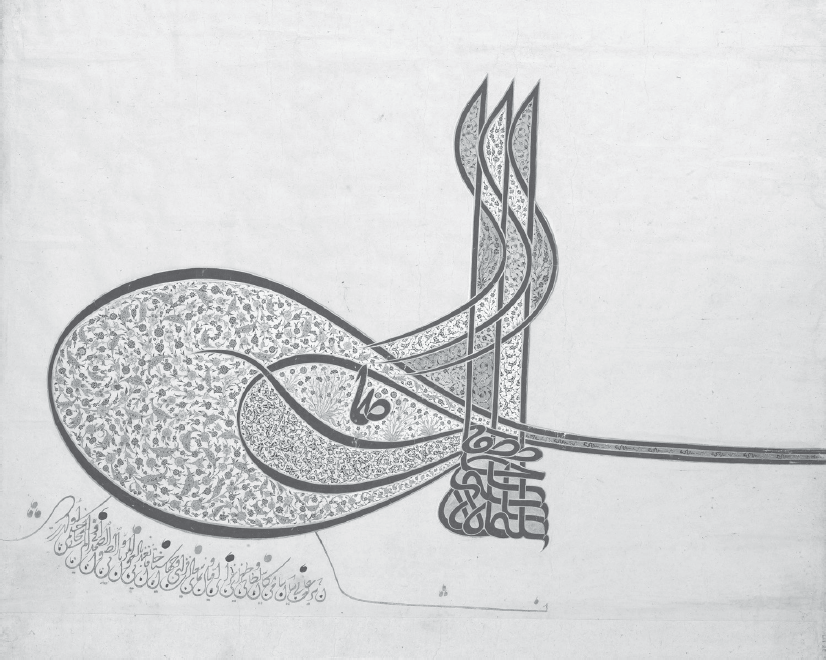

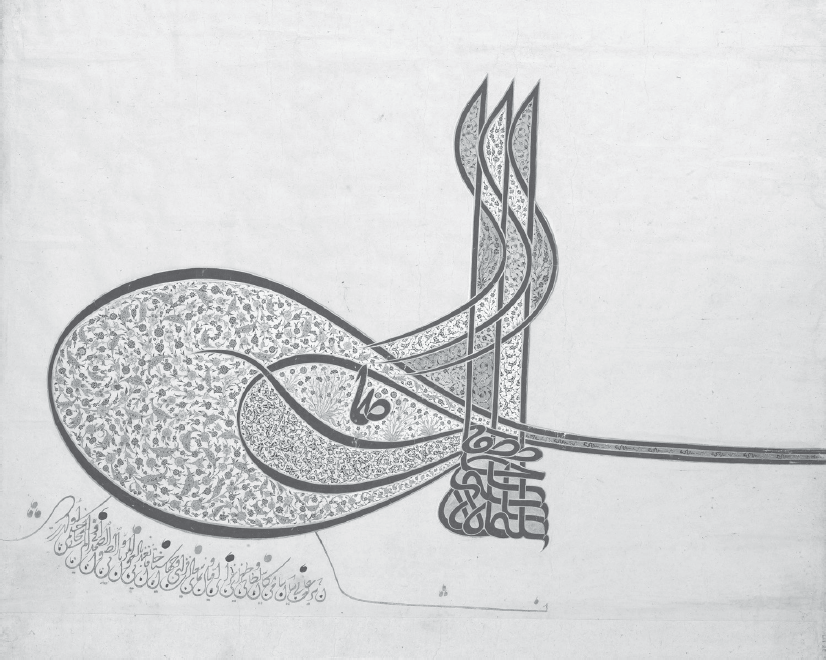

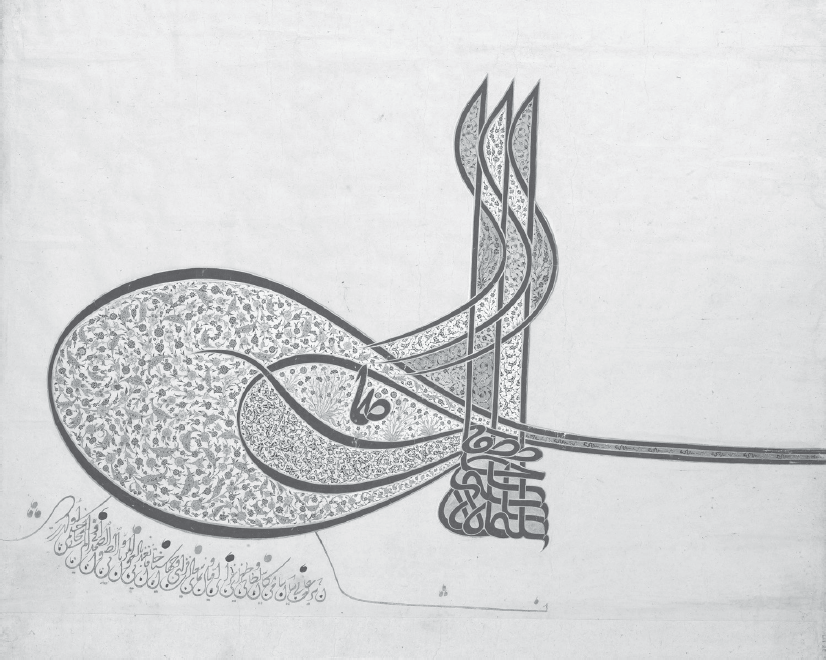

FIGURE 4.2 Tughra of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

A mid-sixteenth century Ottoman tughra (insignia) belonging to Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The imperial tughras were included on all official documents, royal decrees, coins, and diplomatic correspondences. The tughra’s intricate design was not only meant to inspire awe, but also made difficult to forge.

Date: c. 1555–60

Place of origin: Istanbul, Turkey

Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1938. 38.149.1.

Bidlisi composed Qanun-i Shahanshahi (The Essence of Kingship) toward the end of Bayezid II’s reign (r. 1481–1512). The Essence of Kingship is a theoretical exposition of what he narrated in his Eight Gardens. In the latter work, Bidlisi was not shy in depicting Ottoman rulers as the true caliphs of their respective ages. His theory of the caliphate accords an uncontestable legitimacy to Ottoman sovereignty in a competitive Eurasian spiritual space full of formidable opponents, including rebellious shaykhs at home and messianic dynasties abroad such as the Safavids who claimed legitimacy based on their sacred Shiʿi ancestry, as discussed by Hani Khafipour in the previous essay.

It would be instructive to view Bidlisi’s conception of caliphate alongside the perspective of another Ottoman statesman, Lutfi Paşa (d. 1563), who served as a grand vizier during the reign of Suleiman (r. 1520–1566) from 1539 to 1541. In retirement, Lutfi Paşa devoted himself to scholarship and composed works in statecraft, history, jurisprudence, and theology.

In an important but somewhat less popular work, Khalas al-Umma fi Maʽrifa al-ʼAimma (Deliverance of the Community in Recognizing the Leaders), Lutfi Paşa defended the Ottoman ruler’s right to claim the titles imam and caliph in order to refute the juristic dictum that the supreme rulership of a Muslim community is the exclusive reserve of the tribe of Quraish to which the Prophet Muhammad belonged. By drawing evidence from a wide spectrum of sources ranging from Sufism to jurisprudence, Lutfi Paşa reduced legitimacy to acquisition of executive power. He ruled out all other conditions stipulated in juristic theory for the legitimacy of the imamate/caliphate, including justice and being a Muslim, considering them characteristics of good governance rather than requirements for the supreme rulership of the universal Muslim community.

The supreme leader (imam-i aʽzam) is a sovereign sultan who rules over most cities of Muslims such as those of the Rum, Arab, Hijaz, Yemen till the end of seas, the Arab Iraq, Baghdad, Diyarbekir, Morocco, and cities of Hungary all the way to the far end of Germans. At the time of conflicting events, his shadow covers conditions of time like Sultan Suleiman b. Selim Han b. Bayezid Han, who is the leader of time (imam-i zaman) in upholding religion and protecting the realm of Islam with the noble Shariʿa.

If asked, who is Sultan Suleiman? Is he the leader of time or not? Then we answer as follows: No doubt, he is the leader of time. He is the defender of the religious law. So are his deputies and governors. The scholars of time help him. So do the sultans of the Arab, the Turk, the Kurd and the Persian. As mentioned, he has many cities under his control. The definition of leader suits him. He is the deputy (kaʽim makam) of the Prophet in upholding the religion. Thus it is incumbent upon the whole community to obey him.1

In contrast, Bidlisi’s The Essence of Kingship reflected the triumph of Sufism in post-Mongolian political thought from Nile to Oxus, and he built his entire political philosophy on the Sufistic conception of the caliphate. Despite his juristic credentials at the highest level, The Essence of Kingship does not display a trace of the juristic theory of kingship. His political thought reflects a wide range of ideas drawn from different intellectual traditions assimilated into Sufism. Above all, Bidlisi is a Suhrawardian. Similar to the illuminationist Sufi-philosopher al-Suhrawardi, who was executed in 1191 by Salah al-Din because of his political views, Bidlisi’s concept of the caliphate rests on the knowledge of God and being endowed with His traits as His true vicegerent on earth. He draws a clear distinction between the true caliphate and that of appearance; the former is defined to be a cosmic rank only to be attained in the spiritual realm, whereas the latter is a temporal kingship defined as executive power. This conception puts the sultan and the pauper on equal footing for acquisition of the caliphate. Whether hidden or known, the world is never deprived of a caliph as the true ruler of the age. This view comes to light in the excerpt translated below.2

Translation

EXCERPTS FROM BITLISI’S THE ESSENCE OF KINGSHIP

The first proposition of the introduction is on verifying the truth of the vicegerency of God’s lordship (khilafat-i rabbani); the second proposition is on establishing the world’s need for rulership and governance of the world: “Here is Our record that tells the truth about you” (Q. 45:29). Know that, when God granted man the honor of “verily we have honored the children of Adam” (Q. 17:70), He made man precedent and recipient of His bounty over all other elements of the universe, ennobled and honored him by exalting him among the creation, and elevated him to the leadership of the created. First, He made him the manifestation of His attributes of perfection in entirety, and an assembly of His qualities of beauty and majesty. In accordance with “I molded Adam’s clay with My own hand,” He cast Adam’s constitution in two natures by mixing two corresponding but opposite essences. He lightened the candle of Adam’s heart from the torch of His sacred light: “So, when I have made him and have breathed into him of My Spirit” (Q. 15:29). One substance of man is from the realm of spirits and incorporeal beings whereas the other is from the realm of nature and corporeal beings. The substance of his spiritual essence comes from the realm of heavens and the source of happiness. The substance of his corporal body is made from the material realm. With his sublime substance, he belongs to the angels of heavens, and with his base substance he belongs to the level of animals and other material compounds. Combining these two substances makes him exceptional and exalted among the existent entities (aʽyan-i mawjudat). Thanks to his state of equilibrium and unification of virtues, he is placed at the rank of vicegerency and nobility. “I am about to place a vicegerent in the earth” (Q. 2:30) alludes to this rank and the quality of being the shadow of God (zilliyyat-i subhani).

This quality of uniting existent entities in man necessitates him to be the manifestation of noble subtleties and the cause of deserving God’s call, “We have set thee as a viceroy in the earth” (Q. 38:26). So much so that someone who comes after and succeeds the former is called a caliph. The caliph, therefore, is expected to display the noble traits of the succeeded. No doubt, only the fortunate and the favored deserve being adorned with the rank of the vicegerency of the Merciful and the leadership of both the spiritual and temporal realms. In accordance with “and He taught Adam all the names” (Q. 2:31), he is innately capable of understanding, realizing, and being qualified with the knowledge of the truth of existence from its beginning to its end. In acquiring divine morals and qualities, which are sublime measures and a felicitous ornament, he is envisioned to be “God created Adam in His own image.”

It has been verified then that the vicegerency of God’s mercy is the fortunate servant’s qualification with traits and perfections of lordship to the extent it is humanly possible, equipping one’s self with praiseworthy human habits in relation to the universal material order, and uniting the visible realm with that of the spiritual. If this receiver of perfections sits on the throne of rulership and glory in this world, then he is called a sultan of both temporal and spiritual realms. These are such sultans as prophets, God’s friends, the four rightly guided caliphs, and the twelve protected imams. Those who are not commissioned with the execution of commands and prohibitions to rule the temporal realm, but unify in themselves perfection of knowledge and action [and] have the qualities of leadership and guidance of humankind, are called the sultans of the realm of meanings (kishvar-i maʽani). They unify gnostic and practical perfections and are known as the flag-bearers of God’s army. As such, certain prophets and God’s friends are honored with “poverty is my honor and I take pride in it.” For eyes that can only see the ostensibly visible, they look indeed poor and pauper. But, in fact, incisive eyes see their reality, that is, as rulers without soldiers and ministers. God says: “My friends are under my domes, no one else knows them but Me.” If the ruler of the temporal realm is not endowed with those spiritual qualities and Godly morality, then he is not worthy of being God’s shadow. In this case, the title “sultan” is nothing more than a metaphor, similar to naming one piece in chess Queen. In reality, a statue without a soul in the shape of a ruler is more visible than drawings on a painting plate: “Dead! Rather, they are alive, but you perceive it not” (Q. 2:154).

The second proposition of the introduction is affirming the method and the manner by which the temporal world’s need for the caliphate of God’s mercy is shown. Know that manifesting the signs of God’s lordship (rububiyya) requires the association of his attributes of knowledge and power. Similarly, the rules of kingship entail that these two attributes of perfection are seen in association in the temporal world. No doubt, the caliphate of God’s mercy, which is the representation of God’s power, should perfectly display these two attributes so that the requirement of caliphate is manifested in God’s caliphate. These two attributes for constituting the axis of all existence display God’s signs of beauty and majesty among mankind. The Prophet, peace be upon him, as the king of mankind and the lord of universal order, was sent to reform souls and give order to the material world. He was sent to explain the primordial beginning and the eschatological end [mabdaʼ va maʽad], and to establish the laws of sustenance among all servants of God and all nations of the world: “We have sent you only to bring good news and warning to all people” (Q. 34:28). It is certain that the purpose of sending messengers and prophets, and of proscribing the obligation to obey rightly guided leaders [aʽimma] and caliphs is a manifestation of divine secrets and guiding to the right path in commands and prohibitions, as pointed in the verse: “Our word has already been given to Our servants, the messengers: it is they who will be helped” (Q. 37:171–72).

At the time of the Prophet’s leadership, all spiritual and material virtues reached perfection: “Today I have perfected your religion for you, completed My blessing upon you, and chosen as your religion Islam” (Q. 5:3). For this reason, until the final hour and the hour of resurrection, nothing from among all the affairs of the world will require sending of a new Divine Law (shariʿa), nor will there be an occasion to designate laws stronger than the shariʿa and the customs and wisdom of the religion of Islam. As the verse “it was only as a mercy that We sent you [the Prophet] to all people” (Q. 21:107) shows, to guide all the nations of mankind in matters of conduct, caliphs and rulers among servants are given two divine laws and righteous guides to show commands and prohibitions at all times: “I have left two things with you. As long as you hold fast to them, you will not go astray. They are the Book of Allah and the Sunna of His Prophet.” No doubt every seeker of happiness who holds fast to these two sound ropes of pure ordinances and unbreakable handles is always protected from deviating from the right path, and his acts and conditions would always conform to God’s will. Now, if he looks into these two world-showing cups that serve as two seeing eyes for his own condition as well as the affairs of the world, then all of his worldly demands and temporal and spiritual goals become closer to goodness and salvation.

Now, know that the purpose of the Book (that is, the Qurʾan) and the Sunna are of two kinds: one for knowledge and one for practice. The reason behind the revelation of the Book and sending prophets is to reform the present and the future, and to facilitate the needs and aims of God’s servants. This condition of perfection in people’s souls is either knowing the primordial origin and the eschatological return, or knowing how to make people’s lives better in the world of generation and corruption [ʿalam-i kawn va fasad]. The purpose of knowledge and philosophy is the cognizance of the first; and the purpose of laws and rules is to know and practice the second in order to attain the spiritual happiness and liberation from corruption and worldly tribulations. Yet each of these two understandings and practices are of two kinds: either the knowledge of the servant [ʿilm-i khadim] or the knowledge of the Served [ʿilm-i makhdum]. Likewise, for the practice, it is either the practice of the servant [ʿamal-i khadim] or the practice of the Served [ʿamal-i makhdum]. The knowledge of the servant is a prerequisite for attaining the knowledge of the Served. Because the knowledge of laws concerns practices and conditions, its order is the reason for the continuity of God’s servants and a precondition for the knowledge of God. Therefore, this kind of knowledge is a requirement for everyone, for the prerequisite for a requirement, which is the knowledge of God, is also itself a requirement. As for the knowledge of the Served, it is the knowledge of unity and cognizance of God with His attribute of perfect unity and praises of beauty and majesty. The knowledge of the Served includes all the knowledge of scholars, intuitive knowledge, and the wisdom of prophets and philosophers.

No knowledge can remain outside this part because knowing the reality of created things and knowing the nature of existence as it stands is impossible without knowing the creator. For this reason, without knowing the necessary being [God], it is impossible to know the realm of possibilities. Acquiring philosophical knowledge and spiritual perfection by knowing impossibilities and nonexistents is not reliable. The possessor of such knowledge of impossibilities is not considered a philosopher or a scholar. As for the practice of the servant, it concerns either people’s means of livelihood or excelling in morality and acquiring commendable habits. The first example is someone who knows how to conduct daily transactions and acquire nourishment and goods. The second example is someone who knows the method of excelling in morality and deeds. This action is necessary and obligatory for those who concern themselves with the affairs of livelihood or who seek eternal happiness. That is to say, the continuity of mankind in the world of elements requires one to acquire the means of life and indispensable necessities of living. The one who seeks happiness in two worlds and interacts with others in commendable ways needs to acquire the etiquette of interaction and learn the habits of companionship.

As for the practice of the Served, it concerns the well-being of all mankind and the reason of the order of laws pertaining to all the inhabitants of the world, such as devoting diligent attention to the management of worldly and religious affairs for the servants of God, helping anyone to reach the right path, guiding them on matters of primordial beginning and eschatological ends, enlightening them on house management and civic life. However, this should be done with justice and righteousness. Now, maintaining this practice and administering God’s creation requires a purified spirit and a possessor of esoteric power who is assisted by a God’s succor such as Prophets, saints, and friends of God who are rulers of the realm of existence. Among the people of appearance, kings and sovereigns rule the world with justice, stay conscious of God’s glory and greatness, and care for God’s people at all times. Those who are blessed with felicity and uphold worldly affairs are called God’s shadow [zill Allah] and God’s caliph [khalifat Allah]. At times, the spiritual caliphate (khilafat-i maʽnavi) and true leadership (imamat-i haqiqi) unite in the personality of one friend of God. Because of lacking rulership in appearance (dawlat-i suri), perhaps most people deny him and continue their oppression. Yet it is reported from prophets and friends of God who looked like poor dervishes that while being poor and powerless they were commissioned with the task of the caliphate of God’s mercy.

At times, the temporal caliphate and external sultanate conform to the laws of prophets (shariat-i nabavi) and customs of spiritual caliphs (khulafa-yi maʽnavi). Such a person could be called a true caliph and commander of the faithful. His commands and prohibitions should be obeyed carefully because God’s command “You who believe, obey God and the Messenger, and those in authority among you” (Q. 4:59) orders obeying God, his messenger, and the holder of authority. Temporal rulers who strive to implement Prophetic laws, maintain justice, protect religion, and engage in raids and wage war deserve to be praised. These are the most virtuous after the prophets and saints, and the most beloved in God’s presence. Because the prophet stated “Indeed, the most beloved of people to Allah on the Day of Judgment, and the nearest to Him in rank is the just ruler [imam].” As necessitated by divine will, at all times, from among the rulers of the world and caliphs of mankind, one from each of these two parts enjoys the rank of a caliph, either in appearance or in reality, in order to perfect souls and reform both the ruler and the ruled. The world is never bereft of these two types, as told by the Prophet: “A group from my community never stops fighting righteously helping those who serve them until the last of them fights Antichrist.”

As shown with these premises, just rulers are manifestations of God’s power, for reforming people of the time with the majesty of kingship. Prophets, rightly guided leaders [a’imma], and scholars are manifestations of divine knowledge, for promulgating laws of prohibitions and obligations, and endless wisdom.

A LOOK AT HASAN KAFI EL-AKHISARI’S CAREER

Hasan Kafi (d. 1615), a prolific Ottoman scholar and judge, was born in Prusac, Bosnia-Herzegovina, also known as Akhisar (white castle), from which his toponym Akhisari derives. He received his medrese education from prominent scholars in Istanbul and spent most of his life as a provincial judge in the Balkans. He authored well-regarded works on grammar, logic, jurisprudence, theology, biography, and government. By far his best-known work is Usulu’l-Hikem fi Nizami’l-Alem (Elements of Wisdom for the Order of the World). He first composed the work in Arabic and presented it to high-ranking Ottoman statesmen during Mehmed III’s Eger campaign of 1596. Upon request, he soon translated it into Turkish, and it instantly gained popularity among Ottoman readership and earned him the sultan’s favor. In addition to its various editions in Turkish and Arabic, the work has been translated into several European languages since the early nineteenth century. Bosnian scholars have displayed a special interest in studying Hasan Kafi and his works as he has been considered a home-grown cultural icon. He is still considered a saint by many in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and his tomb is a place of veneration.

Elements of Wisdom is a reform treatise that criticizes malpractices in administration and calls for the restoration of the ancient law (kanun-i kadim). Invented first by the sixteenth-century grand vizier Lutfi Pasha (d. 1563), the author of Deliverance of the Community discussed previously, this new genre of political writing became increasingly popular among Ottoman statesmen because it purported to have materialized the ideal polity in Ottoman practice that rests on law and institutions rather than the ruler’s moral qualifications. In Usulu’l-Hikem, Hasan Kafi mentions two medieval works as his sources, Baidawi’s (d. 1286) Qurʾanic commentary Anwar al-Tanzil, and Zamakhshari’s (d. 1144) book of parables Rabi al-Abrar. He uses these works only to quote moral stories to illustrate his arguments and make his work more binding on the authority of these two influential scholars. He wrote the treatise to “renew the principles of world order,” which he observed to have been corrupted since the year 1572. Hasan Kafi summed up the causes of this corruption as failure to maintain justice, meritocracy, consultation, and military technology accompanied with the spread of bribery and breaching spheres of authority.

Hasan Kafi’s proposal aimed to restore the constitution of Ottoman polity, which rests on the proper administration of four principal orders that composes the body politic. The idea of an ideal society composed of four or more groups is very common in works of statecraft, especially those written in the Persianate tradition. With Hasan Kafi, the idea turned into a constitutional principle, an indispensable ingredient of order and good governance from which all laws of government emanate. In this scheme, every group had its own rights and obligations for the body politic to function in an orderly fashion. These rights and obligations were to be maintained through established customs and laws decreed by the ruler. The very reason for the existence of rulership and the primary objective of the ruler was to keep this order in balance by keeping each group within its own sphere of activity and preventing breaches.

Hasan Kafi makes it starkly clear in the excerpt below that if this balance of order is broken the collapse of kingship becomes imminent.3 He therefore shifts the focus of political thinking from kingship to society and accords the ruler and his administration only an instrumental value.

Translation

EXCERPTS FROM HASAN KAFI’S ELEMENTS OF WISDOM FOR THE ORDER OF THE WORLD

The introduction of the book concerns the reasons behind the order of the world. The reason of the order of the world is that, indeed, God predicated the continuity of the world on the continuity of humankind. Namely, He willed that as long as humankind continues to exist, so will the world until the time comes to an end, which is the doomsday. Similarly, he made mankind’s continuity contingent upon procreation. Procreation occurs through interaction and pairing, which depends on wealth. Wealth, in return, is only gained through transactions among people. This necessity requires the existence of laws through which the interests of people are protected at all times. In response to this necessity, previous scholars and intelligent men, with inspiration from God, organized humanity into four groups. They assigned one group to the sword, one to the pen, one to farming, and one to crafts and commerce. Then they called controlling and administering these four groups kingship.

The first group, assigned to the sword, consists of kings, ministers, deputies such as governors and similar officers, and other assistants and soldiers who serve the sword. But what is their assigned task? They are responsible for governing all four groups with justice and good governance, not on the basis of their own convictions but in conformity with the measures and opinions of scholars and the intelligent, lest they err. It is incumbent upon this group to engage in warfare in order to defend all from enemy incursions and to render other similar services expected of kings and governors, as will be explained.

The second group, assigned to the pen, consists of scholars, the intelligent, the pious, the weak, and people who make prayers, namely, those who are incapable of fighting but could only engage in prayers and invocations. If you ask: “what should their task be?” Then we answer as follows: Their responsibility is to oversee God’s commands and prohibitions. Namely, they undertake the task of “commanding good and forbidding wrong” by writing books, reporting by tongue, and telling the ordinances of religion to all other groups. Further, they are responsible for counseling, teaching religious sciences and practices, persuading people to observe religion, and convince them to live in peace. In good faith, they should make prayers for the well-being of people and the ruler, for in comparison to society, a ruler is like a heart in a body. So long as the heart remains healthy so does the whole body.

The third group, which is assigned to farming, cultivates grains, vineyards, and fruits. They are better known in our time as common people. Their task is to provide what is needed for survival such as growing grains and fruits, and work to raise animals that are necessary for living so that they are sufficient for the consumption of all other groups. After knowledge and raiding for faith (ʿilm ve gaza), their service is the most valuable.

The fourth is assigned to crafts and commerce. These are craftsmen who know various arts and skills. Their obligation is to work on what is necessary for crafts and goods of exchange as well as what benefits the public from among the suitable works of craftsmen and merchants.

If you inquire about the question of an able and intelligent person who remains outside these four groups, the answer is that, according to the philosophers of the Muslim community, these kinds of people should not be left on their own. On the contrary, they should be pulled and placed in one of the four groups by force so that no group suffers. Some philosophers ruled that such riffraff who continue to live with no benefit to others should be killed because their existence is a burden to and harmful for all others. At the time of previous sultans—may God forgive them—such idle people would be inspected every year and prevented from staying as such. For example, because it was difficult to prevent the blacks (arab taifesi) [from social mobility] there were strict prohibitions enforced at ports to prevent them from crossing to the Rumelia province. This is why in the old days productivity and God’s bounty were ample in the realm of Rum. I wish these inspections would continue in our time as well so that people are not allowed to be idle.

To maintain order in government and the realm, it is imperative that each group engages in their respective occupation. If each group displays negligence and laziness in upholding their assigned occupations, it leads to corruption of order and deterioration of conditions in the realm. As learned from this rule and measure, it is not appropriate to remove someone from his assigned occupation and force upon him the occupation of another group. No doubt, this kind of enforcement and assignment leads to change and corruption. In fact, negative change and corruption of the past few years have occurred for this reason. Because villagers, craftsmen, and urban dwellers are sent off to the frontiers and forced to wage war, the cavalry and foot soldiers neglected combat, officers slackened, and means of living deteriorated. In provinces, shortage reached to such a degree that goods that could once be bought for one silver coin could not be found now for ten silver coins. Sending producers and townsfolk to the frontiers by force is not an ancient custom but has taken place since the year 1000 [1592 CE]. Especially in the Herzegovinan and Bosnian frontier, during military campaigns, commanders have been sending recruiters to the province to force cultivators from villages as well as Muslims and craftsmen from towns to join military campaigns. As a result, the poor cultivators failed to produce, community prayers are abandoned in towns, and shortages and troubles spread across the province. Consequently, the soldiers too were struck by afflictions and started to desert.

As long as the ruler’s administration conforms to the ancient order, namely, he rules in accordance with the religious law, ensures that people are placed in their proper groups and occupations, then his government and realm thrive in order, the condition of people improves, and kingship becomes stronger. If these ancient customs and commendable paths are neglected, then corruption spreads to the realm and kingship. Then weakness afflicts the kingship from all four directions to the extent that it may require the transfer of authority to someone else.

O Allah: Protect the realm of Islam from corruption. O Lord: Remove the existing corruption and protect us in the future. O Lord: Protect the Ottoman reign from afflictions leading to the transfer of authority.

NOTES

1. Lutfi Paşa. Halas al-Umma fi Maʿrifa al-A’imma. MS, SK, Ayasofya 2877, 22b.

2. Hakim Idris ibn Husam al-Din Bidlisi, Qanun-i Shahensahi, ed. ʿAbd Allah Masʻudi Arani (Tehran: Markaz-i Pazhuhishi-i Miras̲-i Maktub, 2008 or 2009), 7–15.

3. Mehmet İpşirli, “Hasan Kafi el-Akhisari ve Devlet Düzenine Ait Eseri Usulü’l-Hikem fi Nizami’l-Alem,” Tarih Enstitüsü Dergisi 10–11 (1979–80): 251–53.

Black, Antony. The History of Islamic Political Thought: From the Prophet to the Present. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Darling, Linda. A History of Social Justice and Political Power in the Middle East: The Circle of Justice from Mesopotamia to Globalization. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Fleischer, Cornell H. Bureaucrat and Intellectual in the Ottoman Empire: The Historian Mustafa Ali (1541–1600). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Howard, Douglas A. “Ottoman Historiography and the Literature of ‘Decline’ of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.” Journal of Asian History 22 (1988): 52–77.

Imber, Colin. Ebuʾs-Suʾud: The Islamic Legal Tradition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Inalcık, Halil. “Dervish and Sultan: An Analysis of the Otman Baba Vilayetnamesi.” In The Middle East and the Balkans Under the Ottoman Empire: Essays on Economy and Society, ed. H. Inalcik, 19–37. Bloomington: Indiana University Turkish Studies, 1993.

Kafadar, Cemal. “The Question of Ottoman Decline.” Harvard Middle Eastern and Islamic Review 4 (1997–98): 30–75.

Karateke, Hakan. “Legitimizing the Ottoman Sultanate: A Framework for Historical Analysis.” In Legitimizing the Order: The Ottoman Rhetoric of State Power, ed. Hakan Karateke and Maurus Reinkowski, 13–52. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

Murphey, Rhoads. Exploring Ottoman Sovereignty: Tradition, Image and Practice in the Ottoman Imperial Household, 1400–1800. London: Continuum, 2008.

Sariyannis, Marinos. Ottoman Political Thought Up to the Tanzimat: A Concise History. Rethymno, Greece: Institute for Mediterranean Studies, 2015.

Thomas, Lewis V. A Study of Naima. Ed. Norman Itzkowitz. New York: New York University Press, 1972.

Yılmaz, Hüseyin. Caliphate Redefined: The Mystical Turn in Ottoman Political Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018.