JANE MIKKELSON

Every succession in the Mughal dynasty was a tensely anticipated event, a time of contestation and uncertainty that frequently erupted into violence and chaos.1 As Timurids, the Mughals were inheritors of the difficulties attending the Central Asian tradition of collective sovereignty: in lieu of primogeniture (the automatic transfer of imperial power to the eldest son), the corporate dynastic structure and appanage practice (distribution of land and power among several members of the ruling family) central to the Timurid political system ensured that no succession had a predictable outcome. Princes plotted against each other, often long before the end of their father’s reign, and each was supported by various factions and women in the royal family who, as you shall see, played a decisive if not always visible role.2

The war of succession between the four sons of Shahjahan (r. 1628–1658)—princes Dara Shukuh (d.1659), Shah Shujaʿ, Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), and Murad Bakhsh—was no different. When Shahjahan’s health began to fail in 1658, all four sons began to maneuver against each other. After several battles, imprisonments, defections, pardons, hot pursuits, and continuously shifting alliances—all within the span of one year—Aurangzeb finally emerged as the uncontested victor in 1659 and had all rival claimants eliminated.3

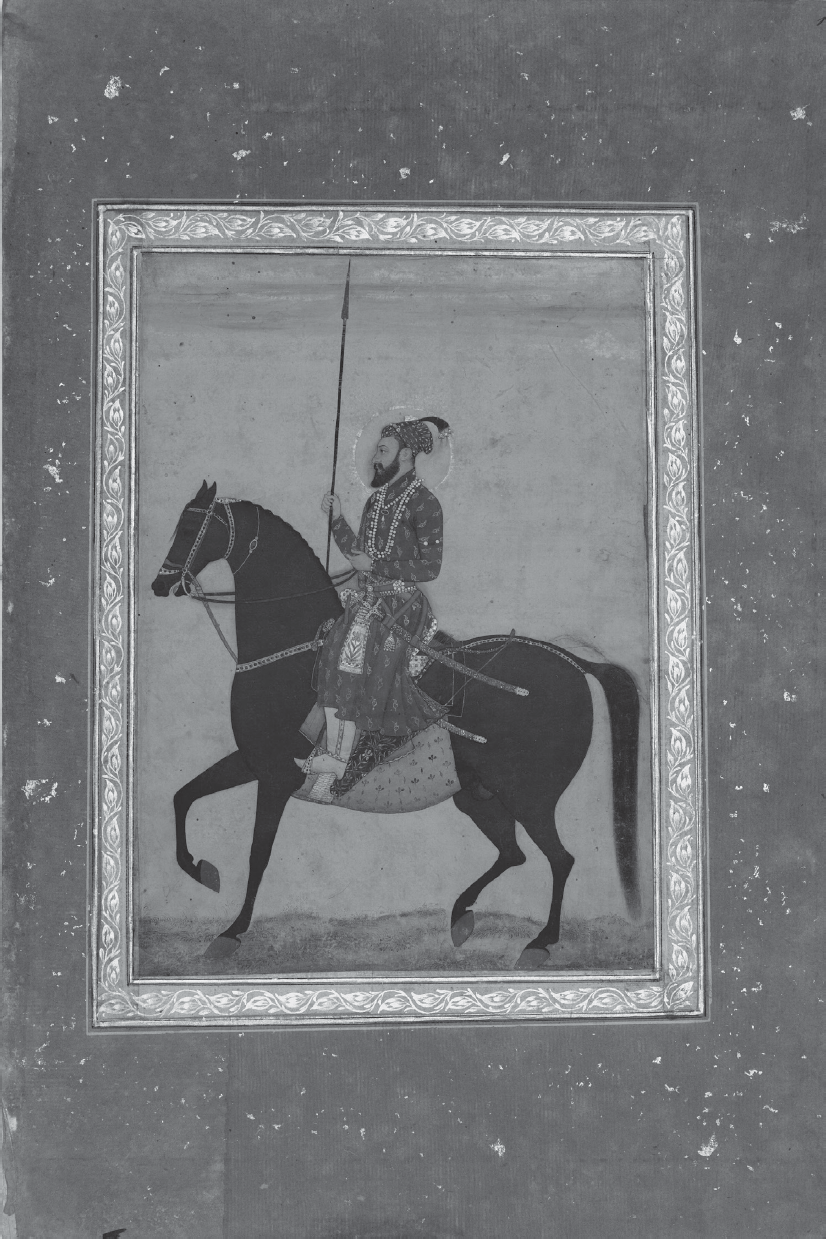

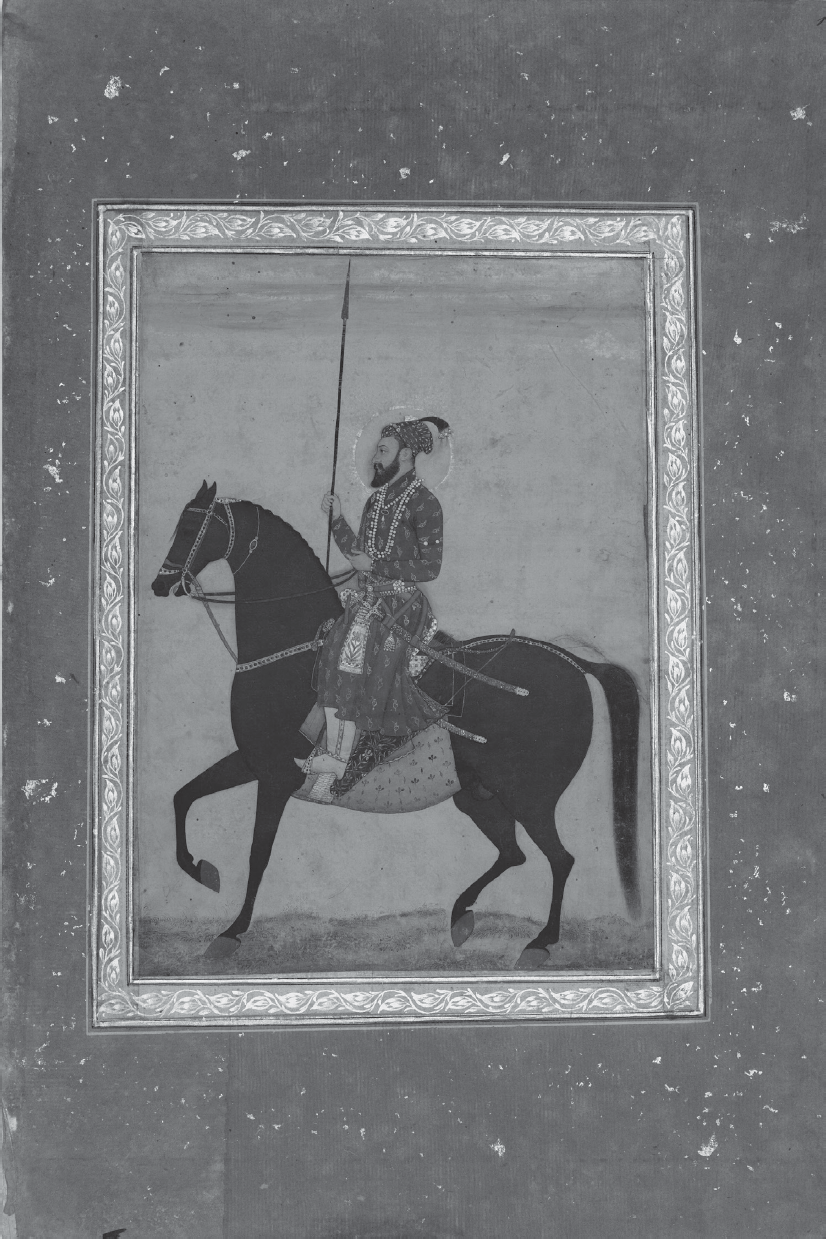

FIGURE 5.3 Equestrian portrait of Aurangzeb

Date: Seventeenth century

Place of origin: Attributed to India

Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1925. 25.138.1

Aurangzeb’s long reign (lasting until his death in 1707) was defined by what some scholars have described as ineffective management of mounting pressures and crises—decentralization, rebellions, economic and financial problems, and a long, costly campaign in the Deccan. Others scholars have described his reign as marked by a broad policy of religious intolerance:4 Hindu temples were destroyed and mosques erected over them; the jizya (a poll tax on non-Muslims) was reintroduced; many Hindus were dismissed from government service; and imperial ideology was remolded into a more narrow shariʿa-minded orientation.5 Aurangzeb is considered to be the last of the “great Mughals,” his rule decisively swerving away from a putative golden age that perhaps reached its zenith with Akbar’s policy of sulh-I kull, or “tolerance for all.”6

As with most decline-and-fall accounts, the narrative form itself makes it all too easy to find a villain, a single person whose conscious choices are made to explain a vast and complex set of processes constituting an overall decline. In many accounts of Mughal history, Aurangzeb has been cast in this role; indeed, his very personality has been judged to be the ultimate reason for the decline of the Mughal Empire: Sir Jadunath Sarkar, for instance, damns him with the faintest praise of being better suited to be “a successful general, minister, theologian, or school-master, and an ideal departmental head” rather than an emperor.7

This kind of historical narrative operates on the logic of contrasts. Although all four princes were involved in the war of succession, in the end, it all came down to a struggle between Aurangzeb and Dara Shukuh, and their conflict was as much a battle of ideologies as a clash of swords. Dara Shukuh, the eldest son and heir-apparent, had long been favored by Shahjahan. If Aurangzeb’s vision of religion and state has been seen as a conscious return to tradition and orthodoxy, Dara Shukuh’s innovative approach to religion has been described as the opposite. Annemarie Schimmel’s characterization of Dara Shukuh and Aurangzeb is representative of the convenient binary formed by these two figures:

[Dara Shukuh and Aurangzeb] manifested in themselves the two possibilities of Indian Islam: Aurangzeb certainly gained the love of those Muslims more oriented to the shariʿa, with their attention centered on Mecca and a distinct Muslim identity; he was equally disliked by mystically minded Muslims and most Hindus. Dara Shukuh, on the contrary, has been considered truly Indian in spirit.8

Dara Shukuh, who was also a Qadiri Sufi, scholar, and poet, undertook several projects that we might today call studies in comparative religion. His scholarly works, such as Majmaʿ al-Bahrayn and Sirr-i Akbar, are rigorous, creative engagements with both Indic and Islamic religious thought, the aim being to bring these two monotheistic traditions into alignment.9 He was fond of quoting the following couplet by Sanaʾi (d. c. 1130), highlighting the merely specious differences between Islam and infidelity:

Kufr u islam har du dar rah-at puyan

“Wahda-hu la sharika la-hu” guyan

Both infidelity [kufr] and Islam travel along your [God’s] road,

Saying: “He is alone, He has no partner.”10

The destinies of these two princes mark a fork in the road of any monolinear historical account of Mughal history; as any such crossroads, it begs the tantalizing counterfactual question of how the subsequent course of history might have unfolded on the path not taken, that is, had Dara Shukuh succeeded to the throne instead of Aurangzeb. But such narratives and caricatures often purchase their explanations at the price of context and detail. Was Aurangzeb only a jealous, narrow-minded bigot? Was Dara Shukuh really a guileless scholar and Sufi with no political ambition? How can these clichéd antitheses be confirmed or dispelled?11

Close reading can add crucial texture to these otherwise crude portrayals: by analyzing original sources with particular attention to style and rhetoric, many finer points can be gleaned that address the far more interesting question of how certain contrasting portraits and narratives may have been constructed by the very historical figures in question. How did Aurangzeb view Dara Shukuh? In Jahanara’s mind, in what ways were her two brothers different? How did Dara Shukuh and Aurangzeb conceive of themselves? All three siblings were clearly very canny verbal tacticians: for them, the strategic arrangement of words on a page was just as much a part of the apparatus of war as the arraying of forces on a battlefield, and all four selections provided here are examples of a highly charged, politically inflected rhetoric where every word matters.

With this in mind, the present translations make no attempt to abbreviate long sentences or delete repetitions. Doing so would risk undermining the structure of Indo-Persian prose thought, wherein complexity of style was not mere mechanical conformity to convention; on the contrary, every seemingly redundant adjective and phrase was carefully positioned by the author within the work’s overall rhetorical architecture. The resulting verbose, at times euphuistic English is therefore intended to convey as much of the original form and meaning as possible.12

(1) Jahanara’s letter to Aurangzeb is an eleventh-hour attempt to dissuade him from engaging in battle with Dara Shukuh.13 She herself shared Dara Shukuh’s religio-political leanings and is writing very much as Dara Shukuh’s ally. Citing the strict Islamic injunction not to wage war during the sacred month of Ramazan, she strongly exhorts Aurangzeb to stay true to his own pious nature and not violate this law. She also refers to the convention that one must obey an elder brother (Dara Shukuh) as one would obey a father—a further implication that Aurangzeb’s actions are not simply unseemly but flout basic social conventions. Her wording is delicate, at times even laudatory, and she stops just shy of accusing Aurangzeb outright of being a bad Muslim. By construing Aurangzeb’s (potential) actions as rebellious and seditious, and by appealing to what she calls his fundamentally just and pious nature, Jahanara draws a line on the moral battleground, raising specific issues that later historians would have to spin with considerable delicacy in official histories.

(2) The excerpt from Muhammad Saqi Mustaʿidd Khan’s history, the Ma’asir-i ʿAlamgiri (completed in 1710), provides an official version of the events of exactly one year (from September 1658 through September 1659). As such, it is unsurprisingly packed with fawning praise of Aurangzeb, in which his coming to power is portrayed as a divinely sanctioned blessing. How this is achieved is quite impressive: Aurangzeb is described with relentlessly bombastic diction as an infinitely wise, just, pious, and clement ruler, whose highest ambition is to rid Hindustan of heresy. Dara Shukuh, by contrast, is presented as a malignant apostate, a perverter of true Islam. This history handles certain unpleasant events by clinging assiduously to a narrative of inevitability: deciding to fight (unlawfully) during Ramazan is cast as a decision that Aurangzeb was forced to make with a heavy heart, and only when all other options for peaceful outcomes were exhausted. A certain amount of squeamishness is felt, for example, in the haste with which this otherwise voluble historian describes the execution of Dara Shukuh in a terse passive voice, then immediately launches into a detailed account of Aurangzeb’s many acts of generosity during that time.

(3) Aurangzeb’s letter to his son was composed long after the events of 1658–59, toward the end of his reign. He reflects upon that war of succession as a much older man, and his recollections are colored by the pressing concerns of the present, and by his increasing fear that yet another war of succession would break out among his sons. In this letter, he mentions Dara Shukuh, who, as he says, also had a rightful claim to the throne—which he lost on account of his greed and filial disobedience. Aurangzeb’s letters offer a stunningly personal self-portrait of a ruler whose orthodox piety is certainly evident: in one letter, he chastises one of his sons for celebrating Nouruz (a pre-Islamic Persian new year festivity), referring to this custom of “the people of Iran, demons of the desert” (mardum-i irani ghul-i biyabani) as a (bad) innovation (bidʿat; that is, as something without precedent in the Islamic tradition).14 But he also contemplates quite self-reflectively, and often elegiacally, his legacy and the future of his empire. Aurangzeb’s correspondence reveals that he was not afraid to get his hands dirty in the mundane affairs of governance and that he had an extraordinary degree of personal involvement in routine bureaucratic matters (ensuring the appointment of qualified persons to various posts and so forth). Frequent citations of classical Persian poets such as Saʿdi, ʿAttar, and others calls into question the stereotypical image of him as an ill-humored, austere reviler of poetry. Some letters contain nuanced, invaluable meditations on abstract matters, such as the nature of kingship (badshahi)15—leaving little doubt that he took the duties of his office very seriously.

(4) Dara Shukuh’s lyric poems (ghazals) are undeniably polemical. In one ghazal, his bragadoccio claims about the high order of both his spiritual and political achievements blend together seamlessly:

Having beheld you [God] in entirety [dar kull]

Qadiri16 concluded universal peace [sulh-i kull],17 abandoning rebellion [ʿinad].18

In another poem, he does this with still more daring bluntness:

That Muhammad [the Prophet] was king of messengers [shah-i rasulan bud];

This Muhammad [Dara Shukuh] would be king of kings [buvad shah-i shahan].19

The undisguised political ambitions evident in these poems remind us that the picture of Dara Shukuh as an apolitical pacifist whose attention was confined to academic and theological pursuits needs to be taken with a sizable grain of salt.20

In translating these ghazals, no attempt was made to render them into poetic English because the aim has been to show as literally as possible how Dara Shukuh made use of certain central terms (such as haqq [truth/God/the real],21 and kufr and islam [infidelity and Islam]). Perhaps this is not a great loss; although his poetry is very interesting in terms of revealing his political, religious, and ideological sensibilities, he cannot be said to figure among the great lyric poets of his time.

TRANSLATION

Letter to Aurangzeb from Jahanara, His Sister

Praise be to God and his bounty that the holy body of the Emperor [zat-i muqaddas-i shahinshah]—the Seeker of Justice [maʿdilat-puzhuh] and Discerner of Details, His Most Exalted Majesty [aʿla hazrat], Shadow of God, Object of Our Lord’s Merciful Gaze, Second Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction [sahib-qiran-i sani; that is, Shahjahan22]—is unencumbered by the many infirmities and illnesses that necessarily attend the human condition. [Shahjahan’s] world-adorning attention is fully directed toward ensuring the welfare of [his] subjects—both nobles and commoners alike—who have been entrusted to his care by God, and toward the security of the kingdom. [Shahjahan’s] most noble and equitable nature does not permit him to tolerate anyone—especially his fortunate children and renowned sons—fomenting such disturbances that lead to the distress of the populace and the harm and oppression of all peoples [tavaʾif-i anam].

Now that [Shahjahan’s] sacred thoughts are wholly occupied with how best to repair such weaknesses that entered into the affairs of nobles and commoners on account of the illness that had afflicted that Chosen One of the People and the World [Shahjahan], stoking the flames of insurrection and rebellion [fitna u fisad] and igniting the fires of hatred and hostility [kin u ʿinad], which (heaven forefend!) will kindle the desolation of countries and the ruination of worshippers, can only increase the distress of [Shahjahan’s] blessed mind and cause great anguish to his holy nature. This undesirable display from that wise, enlightened brother [that is, Aurangzeb], who is adorned with elegant virtues and generous conduct, and who possesses laudable manners and a sound disposition, would be extremely wicked and unbecoming.

It was necessary that this letter be composed with benevolent intentions, consisting in great benefits and motivating the cleansing and purifying of [one’s] inner courtyard [conscience; sahat-i batin] and clearing the path of return [to Paradise; tasfiya-yi tariq-i maʿad] of any weeds and debris of corrupt matters and reprehensible transgressions. If the intention of that noble brother that is, Aurangzeb] in this matter is to stir up the dust of revolt and rebellion [fisad u ʿinad] and to stoke the fires of battle and slaughter, he might justly judge for himself how extremely distressing it is to prepare for war, conflict, battle, and slaughter to further [one’s] ambition to “spill the blood”23 of the innocent, and to fire arrows and muskets in the presence of His Majesty in opposition to the True Guide [murshid] and Qibla [that is, Shahjahan]—whose pleasure is tantamount to the pleasure of God (may He be exalted and glorified) and the Messenger (may God honor him and grant him peace). The fruits of such actions can be only infamy and ruin. Even if [your] preparations for the turmoil of mutual enmity and conflict are not provoked by the Fortunate Prince [shahzada-yi buland-iqbal24; that is, Dara Shukuh], this still cannot be condoned by the principles of wisdom; for according to Islamic and conventional law alike, an elder brother has the judgment of a father [hukm-i pidar darad]. [Aurangzeb’s action] are a certain and complete departure from all things that please the mind of His Holy Majesty, Shadow of God [Shahjahan] and the demands of his exalted imperial nature.

In sum, when that prudent and noble brother [Aurangzeb], who is credited with laudable deportment, virtuous manners, and a generous nature that is famous throughout the world, who ever endeavors to please the most noble mind of the fortunate Emperor and angelic King [Shahjahan], stirs up the dust of war, kindles the flames of conflict, prepares for battle and bloodshed, and decides to fight and foment rebellion—that is in no way agreeable to anybody. Is it wise to trade a few days’ delay in this impermanent, unstable realm and [partaking of the various] enjoyments that bewitch the foolish [inhabitants] of this borrowed [temporal] world for perpetual damnation and infamy of the eternal world? Hemistich:

Don’t do this, don’t do this; those who are virtuous do not act thus.

It is suitable for that honorable brother [Aurangzeb] to deem it necessary to distance himself from these corrupt matters and reprehensible actions…and to strive to please the holy mind of the religion-fostering King and justice-spreading Emperor [Shahjahan] as much as possible. [Aurangzeb] ought to consider [striving to secure] the happiness of His Majesty [Shahjahan] as a way of attaining bliss in both realms [in the here and hereafter], and he must be wary of spilling the blood of the followers of the Seal of the Prophets [Muhammad; that is, the blood of Muslims] during the blessed month of Ramazan. He [Aurangzeb] ought to obey the laws [ahkam] that are already obeyed by the people and that are given by the Guide and Lord of Beneficence, Master of Sultanate and Empire [Shahjahan]. For verily the meaning of the Qurʾanic phrase “those among you who command”25 is the king; whereas to start down the path of opposition to the caliph of God [khilaf-i khalifa-yi ilahi] is to oppose God.

Should your have any further objectives, it would be wise and agreeable for you to decide to halt in whatever place you have pitched your tents, and to write down all your demands so that they may be presented to His Holiness [Shahjahan] and handled in accordance with whatever you desire in your heart. Sincere efforts will be made to satisfy and fulfill the aims and desires of that apple of the eye of the sultanate and government [that is, Aurangzeb].

Excerpt from Muhammad Saqi Mustaʿidd Khan’s Ma’asir-i ʿAlamgiri

On the eighth of Zu l-hijja of the year 1068 [September 6, 165826], the health of the Second Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction [sahib-qiran-i sani], the Emperor and Warrior of the Faith, Shahjahan—hereafter, His Most Exalted Majesty became afflicted with a sudden ailment in the capital [Delhi] and retired from the occupations of world-governance. Dara Shukuh, the eldest son of His Most Exalted Majesty, took advantage of this opportune moment and barred the arrival of news to the provinces. In this way, disorder made its way into the realm; Murad Bakhsh, the fourth son of His Most Exalted Majesty and governor of Gujarat, ascended the throne, and Shah Shujaʿ, the second son of His Most Exalted Majesty, did the same in Bengal, leading his army toward Patna. Fearing the power of the fortune of the lord of the times [Aurangzeb], Dara Shukuh repeatedly attempted to divert the disposition of His Most Exalted Majesty away from this partaker in the good fortune of eternity [Aurangzeb], and, through divers deceptions, caused [Shahjahan] to recall back to court the armies that had been sent to assist the king [Aurangzeb] in guarding the provinces. After that, intending to eliminate Shujaʿ and Murad Bakhsh during His Most Exalted Majesty’s lifetime and with his assistance, [Dara Shukuh] turned with composure to the matter of the Deccan and to sorting out the affairs of this divinely chosen one [Aurangzeb], and undertook to convey His Majesty to Akbarabad [Agra] during the very peak of his illness…. Through the subterfuges of Dara Shukuh, His Most Exalted Majesty experienced a change of heart regarding him who is fortunate in eternal matters [Aurangzeb]. [Shahjahan] imprisoned ʿIsa Beg, [Aurangzeb’s] government agent, who had not committed any crime, and ordered the seizure of his properties and possessions; after a while, however, comprehending the indecorous nature of this action, he released him from prison.

Of the various kinds of abominations perpetrated by Dara Shukuh, the greatest cause of the lord of Islam’s [Aurangzeb’s] wrath was Dara Shukuh’s inclination toward the practices of the Hindus [aʾin-i hunud] and his propagation of the style of taking liberties [with what is forbidden by Islamic law] and heresy [tariqa-yi ibahat va ilhad]. For this reason, considering it imperative to preserve the laws of religion and state [namus-i din va dawlat], [Aurangzeb] resolved to set out and pay his respects to His Most Exalted Majesty and to convey Murad Bakhsh [to court as well], because, although he had perpetrated ignorant actions, he [had in the meantime] grasped the hem of royal benevolence, begging for [Aurangzeb’s] intercession…. Heeding the demands of prudence, [Aurangzeb] assembled the accouterments of battle, and on the first day of Jumada l-ula of 1068 [February 4, 1658], he departed from Aurangabad in the direction of Burhanpur; on the twenty-fifth of this month [February 28, 1658], the shadow of [Aurangzeb’s] arrival was cast upon the court of Burhanpur, and he dispatched a letter to His Most Exalted Majesty expressing [his desire to] visit [Shahjahan while he was ill]. For one month, there was no response; and all the while, dreadful news kept arriving, [such as that of] Jaswant Singh’s defection [to Dara Shukuh’s side] at the instigation of Dara Shukuh. On Saturday, the twenty-fifth of Jumada l-ukhra [March 29, 1658], [Aurangzeb] unfurled the banners of his attention toward the abode of the caliphate, Akbarabad [Agra], and on the twenty-first of Rajab [April 24, 1658], during the march from Dipalpur, Murad Bakhsh, who had come from Ahmadabad adorned in the attire of pilgrimage to circumambulate the Kaʿba of the state [to beg humbly for Aurangzeb’s forgiveness], arrived to pay his respects…. [Dara Shukuh], whose religion is heresy [an zalalat-kish],27 prepared for battle….

Placing trust in God, the king arrayed

The victorious army to the right and to the left.

All the soldiers were determined and patient;

Everyone was of a single mind, placing their trust in God.

Jaswant Singh hoisted the banners of ignorance and misfortune, straightened the ranks, and mounted his horse in readiness for war; the two armies engaged in battle. Although the Hindu forces were as numerous as a host of heavy clouds, the fire-raining swords of the victorious warriors for religion [mujahidan] burned the harvest heap of those lives imprisoned by divine wrath [ghazab-i ilahi], and lethal arrows loosed by the brave men [of Aurangzeb’s army] pierced their enemies’ chests, repositories of their own misfortune that had become targets for the arrows of imperial anger [qahr-i shahinshahi]. In the end, Jaswant Singh chose to flee the scene of battle ignominiously with a number of his men, and they crept away in the direction of his homeland, Marvar.

The terrified, timorous ones fled in such haste

That they tore off their heavy sacred threads [zunnar]

…The beauty of victory was stunningly reflected in the mirror-like swords of the warriors for religion of the glorious army [of Aurangzeb]; all plundered possessions were confiscated, and the imperial tally counted nearly 6,000 slain enemy soldiers.

While victory and defeat are the custom of the world,

Victory won’t lend anyone a hand.

When [Aurangzeb] crossed the Chambal River on the first day of Ramazan [June 3, 1658], news of Dara Shukuh’s advance from Dholpur reached [Aurangzeb’s] royal ear. On the sixth day of the blessed month of Ramazan [June 8, 1658], [Aurangzeb] approached the army of [Dara Shukuh] and halted at a distance of one and a half kuruh [kos].28 On that very day, Dara Shukuh mounted his horse and stood at some distance ahead of his camp; however, fearing the charisma and authority of the lord of the world [Aurangzeb; farr-u-shan-i khadiv-i jahan], he didn’t have the courage to take a single step forward. He greatly tormented his own soldiers, who were girded for battle, by keeping them outside in the scorching air; a great many perished from severe heat and dehydration…. The next day, that fierce warrior [Aurangzeb] ordered that the banners of resolve be unfurled, and that his armies march in the direction of Akbarabad [Agra]. On the morning of the same day, the ninth of Ramazan [June 11, 1658]…cannons were shot and muskets were fired from both sides, and the heat of battle blazed. […Several] chiefs of Dara Shukuh’s army were slain by arrows, and although some of his troops were still with him, his resolve began to falter. He descended from his elephant and mounted a horse; seeing that ill-timed action, his army was thrown into disarray and began to flee, and the breezes of triumph swept through the tassels of [Aurangzeb’s army’s] victory-embroidered banners.

These two strange victories became joined this way:

“Victory is from God and conquest is near”29

Many miraculous signs pointed to the good fortune of [Aurangzeb], who was distinguished by divine favor; for instance, so many commanders were killed on Dara Shukuh’s side that in no battlefield anywhere was anything similar ever seen…whereas none of the great commanders of the victorious armies [of Aurangzeb] perished…. Following his defeat, Dara Shukuh arrived at his house of grief in [Agra] by the evening with his son and several of his servants, and when three watches of the night had passed, he departed for the house of the caliphate, Shahjahanabad [Delhi].

Borrowed fortune [dawlat-i ʿariyat] turned its face away from him;

All that the heavens had bestowed upon him was taken back.

…On that same day, [Aurangzeb] sent an apologetic letter to His Most Exalted Majesty [Shahjahan] expressing regret for the occurrence of the battle. On the tenth day of the blessed month of Ramazan [June 12, 1658], the Nur-Manzil garden in Akbarabad [Agra] was graced with [Aurangzeb’s] royal presence; His Most Exalted Majesty [Shahjahan] sent a reply to Aurangzeb’s letter of apology, and on the following day, he sent [Aurangzeb] a sword that was called “the world-conqueror” [ʿalamgir]. High-ranking nobles and other courtiers of the caliphate turned their hopeful faces toward the royal court of the protector of the world [Aurangzeb], arriving there in legions; everyone was distinguished by favors according to their station…. On the twenty-first [June 23, 1658], it came to be known that Dara Shukuh had reached Delhi on the fourteenth of Ramazan [June 16, 1658]. Despite the fact that [Aurangzeb’s] royal wish to attend upon His Most Exalted Majesty had been presented,30 Dara Shukuh had cast His Majesty’s mind into doubt by means of secret written communications. Lord [Aurangzeb], a keen discerner of subtleties, abandoned that intention; on the twenty-second of Ramazan [June 24, 1658] he made his way toward [Delhi]. On the twenty-fourth [June 26, 1658], at Ghatsami, news arrived of Dara Shukuh’s flight from Delhi, and on the last day of [Ramazan, June 30, 1658], [Aurangzeb] appointed Bahadur Khan to pursue Dara Shukuh. Because Murad Bakhsh had prepared for unjust rebellion and, his head full of illusions, was waiting for any opportunity to display his spite, it was necessary for Aurangzeb to take him prisoner at Mathura on the second of Shavval [July 3, 1658], freeing the people from evil and sedition…. When it became known that Dara Shukuh was heading toward Lahore, the kingdom-conquering lord [Aurangzeb] decided to advance on Panjab.

Astrologers had selected a favorable hour on the blessed day of Friday, the first of the month of Zu l-qaʿda 1068 [August 1, 1658]…for [Aurangzeb’s] auspicious accession to the throne; yet because there had been no opportunity to arrive at [Delhi] Fort,…[Aurangzeb] remained at the garden of Agharabad [Shalamar] for a few days, where he acceded to the throne of fortune at the aforementioned hour. On that blessed day, princes, high-ranking nobles, persons of rank, and others acquired such honors as defy the imagination. Men of letters found marvelous chronograms for this accession, and among them is the magnificent Qurʾanic verse: “Obey God and obey the messenger and those in authority among you.”31…

At that time, Aurangzeb heard that Shah Shujaʿ, [Aurangzeb’s] brother—between whom, prior to his prosperity-granting accession, there had been perfect concord and close friendship—emerged from Bengal intent on war. Therefore, on the twelfth of Muharram [October 9, 1658], the banners of return from Multan were unfurled, and on the fourteenth of Rabiʿ al-avval [December 9, 1658], the [Delhi] Fort was illuminated by the charismatic magnificence [farr] of the [emperor’s] arrival. News of Shah Shujaʿ’s seditious stirrings arrived apace. Although it was the wish of [Aurangzeb’s] most enlightened heart to disregard [Shah Shujaʿ’s] connivances, [Shah Shujaʿ] had the temerity to reach the borders of Banaras [Varanasi], clamoring for battle; so it was with disappointment that Aurangzeb ordered Prince Muhammad Sultan to unfurl the banners of departure from Akbarabad [Agra] in that direction on the eighteenth of Rabiʿ al-avval [December 13, 1658]…. The lord of the world [Aurangzeb] wanted to reach a peaceful resolution in the matter of Shah Shujaʿ, so he sent a divine missive consisting of various kinds of advice in order to clarify his [Shah Shujaʿ’s] intentions. However, once he had ascertained that peace and civility would be of no avail, on the fifth of [Rabiʿ al-avval, November 30, 1658], he [Aurangzeb] hoisted the banners opposition….

Dara Shukuh was compelled to prepare for battle; but because he lacked the courage to confront [Aurangzeb’s] imperial forces, he dug trenches along the passes of the hills of Ajmer…. The next day, [Aurangzeb’s] victorious forces advanced half a kuruh [kos] and halted; a beam of sunshine shone forth from [Aurangzeb’s] royal quarters, indicating that the artillery be carried forward…

Cannons and muskets blazed on both sides,

The field of battle was obscured by fire.

…Among the warriors of the faith of [Aurangzeb’s] army, Shaykh Mir, the best among pious nobles, was struck in the chest by musket-fire and became martyred…. Beholding the brave displays of [Aurangzeb’s] victorious army, Dara Shukuh decided to flee for Gujarat, even though his trenches were holding. In this way victory was achieved, an ornament for religion and state [piraya-yi mulk u millat]. Upon hearing the good news of this divinely bestowed conquest, His Highness the Emperor [Aurangzeb] gave thanks to the true granter of victory [God].

It is an undisputed fact that very few territory-conquering kings [padishahan-i kishvar-sitan] have been obliged to fight for the royal throne and authority in this way, during so brief a span of time. This victory-granting king [Aurangzeb] was forced to battle many powerful enemies within a single year. With divine support [taʾyidat-i rabbani], he emerged victorious and triumphant, attaining sovereignty [sarvari] and snatching the highest reed of excellence32 in every battle by the power of his victorious arm and decapitating sword. Despite such displays of courage, extreme humility prevented him from ever attributing [his victories] to his own powers…. He always displayed gratitude for these fortunate blessings by his devotion to God, through his propagation of Islamic law [that was given by] His Excellency, the Refuge of Prophethood [Muhammad], and by the eradication of all traces of innovation and sin [bidaʿ va manahi]. The abundance of splendor and magnificence notwithstanding, [Aurangzeb’s] piety did not permit him to give any part of himself over to the negligence of rest; with abiding wisdom, piety, justice, and solicitous concern for the conditions of the army and his subjects and the laws of justice and equality, he endowed the caliphate with resplendence. I hope that the realm of form and meaning may always be illuminated by the sovereign rule of this religion-protecting lord [farman-dihi-yi in khadiv-i din-parvar]….

Because the first celebration of [Aurangzeb’s first] auspicious coronation had been cut short, and…[many formalities] had been postponed, therefore, when matters of world-conquest were settled, an order was issued to regional governors to make all necessary preparations for these festivities. The organizers put forth every effort in decorating the assembly of pleasure, and on the auspicious day of Sunday, the twenty-fourth of the blessed month of Ramazan of 1069 [June 15, 1659]…the emperor, whose throne was the celestial globe and whose crown was the sun, the world-conquering, justice-nurturing king placed the miracle-working crown of world-governance upon his head, donned the auspicious investiture of success, and ascended the throne of magnificence and glory.

From the east of the imperial throne

Rays of light from the Shadow of God illuminated the world;

The new emperor made the world anew

The soul of the kingdom’s body was renewed again

The dawn of the fortune [dawlat] broke upon the dark night of Hindustan,

And the sun shone into every corner.

…So many trays of silver and gold were distributed in the exalted name of the religion-nurturing king [khaqan-i din-parvar] that [everyone’s] wide purse of hope was filled by collecting that scattered treasure. Everyone standing along the carpet of honor politely placed their hands upon their heads as a sign of fidelity, and uttered prayers and praises of the caliph of the time [khalifa-yi zaman]. The doors to the treasuries of imperial rewards were opened for the people of the world, and colorful robes of honor adorned the eager figures of young and old alike.

Since in previous times the Word of Purity33 had been stamped upon ashrafis [gold coins] and rupees, and this coinage had become eroded by being passed constantly from hand to hand, [Aurangzeb] decreed that it would be better if a different credo were stamped on [his] coins. At that time, Mir ʿAbdulbaqi, whose pen-name was Sahbaʾi, presented his own couplet:

King Aurangzeb, conqueror of the world,

Minted a [new kind of] coin in the world like the bright full moon.

This so pleased [Aurangzeb’s] most holy temperament that he ordered one side of ashrafis and rupees to be stamped with this pleasing couplet, the other side bearing the name of the city in which the coins were minted and the year of accession of elegance and beauty [zib-u-zinat; that is, Aurangzeb]. [Aurangzeb’s] auspicious title adorned the illustrious imperial seal: “Abu z-zafar Muhyi al-din Muhammad Aurangzeb Bahadur ʿAlamgir Padishah-i Ghazi,” and it was ordered that royal mandates bearing the glad tidings of security and tranquility [brought about by Aurangzeb’s] accession be distributed to all provinces of the empire. Lord [Aurangzeb], who was as bounteous as the ocean, opened his generous hands and bestowed prestigious rewards upon all princes of noble lineage and high rank, honored ladies, and other imperial servants. High-ranking nobles and other pious personages all found themselves promoted in station and rank with new honorific titles, and contended among themselves for glory. Appropriate rewards and expensive gifts were bestowed upon multitudes of pious, God-fearing men, and also upon poets, musicians, and entertainers at mirthful gatherings.

A high imperial order was issued that the auspicious festivities continue thus until the tenth of Zi l-hijja [August 28, 1659], at which point they would merge with the arrival of Id-i azha; in this way, during that span of time, everyone’s dearest wishes would be realized and all their long-held hopes fulfilled. The date of [Aurangzeb’s] accession was commemorated by a chronogram penned by Mulla Shah-i Badakhshi, “zill al-haqq” [Shadow of God/Truth]; he also composed the following poem:

The dawn of my heart blossomed like the rose of the sun,

For Truth/God [haqq] has come and swept away false dust [ghubar-i batil].

The date of accession of the Truth-perceiving king [shah-i haqq-agah]

Is known as “zill al-haqq”; verily [al-haqq] this is called the truth [haqq].

One scholar discovered [the chronogram] in “padshah-i mulk-i haft-iqlim” [“Padishah of the Kingdom of the Seven Climes”], and a poet found it in the hemistich

“Zib-i ourang-u-taj-ha-yi shahan”

[Adornment of the thrones and crowns of kings]

Mulla ʿAzizullah, son of Mulla Taqi Isfahani, quoted from the words of God: “Inna l-mulka l-illahi yuʾtay-hu man yashshaʾa.”34

Because the luminous lights of victory cast their rays of fortune upon the earth during the month of Ramazan, [Aurangzeb] ordered that the first day of that month mark the beginning of his reign in [imperial] records and calendars.

Following the custom of Jamshid and Kasravi [Anushervan], [Aurangzeb’s] predecessors35 had considered the first day of Farvardi [Farvardin] to be one of the most important festivals [az ʿid-ha-yi buzurg], and their tradition [rasm] was to celebrate it with much fanfare; the refuge of religion [padishah-i din-panah] Emperor [Aurangzeb] ordered that an imperial celebration be held [jashn-i padishahana] each year during the blessed month of Ramazan instead of the festival of Nouruz, continuing through the auspicious ʿId-i fitr with mirthful customs. This [celebration] would be known as “the joy-illuminating festival” [“jashn-i nishat-afruz”]…Praise be to God that today, by the fortune [dawlat] of the religion-fostering adorner of the imperial throne [Aurangzeb], all of Hindustan has been rid of the contamination of innovations [bidaʿ] and heresies [ahvaʾ].36

Meanwhile, word came from Bengal that Prince Muhammad Sultan [Aurangzeb’s son], who had been appointed along with Muʿazzam Khan to eradicate Shah Shujaʿ, had been taken in by his deceiving ways. On the twenty-seventh of Ramazan [June 18, 1659], he embarked upon a boat with several of his servants with the intention of defecting to Shah Shujaʿ’s side, taking the path of rebellion [mukhalafat]….

At this time, Bahadur Khan conveyed Dara Shukuh to the celestial threshold [Aurangzeb’s imperial court] and was held at the Khizrabad palace. Because for various reasons it became necessary to erase the dust of his existence from the courtyard of the kingdom of the living, on the night of Thursday, the twenty-first of the month of Zi l-hijja [September 9, 1659], the lamp of his life was extinguished, and he was buried in that nest of paradise, the tomb of Emperor Humayun….

During this time, out of generosity toward the common people, [Aurangzeb] ordered that the road tax on stores of grain and other kinds of goods be lifted in perpetuity; therefore, an annual sum of 25 lakh rupees was withdrawn out of the [revenue from] imperial lands [khalisa-yi sharifa]; the accountant of the mind is unable to comprehend all the [monetary and other obligations] that were pardoned [by Aurangzeb] throughout the entire empire.

Aurangzeb’s Letter to His Son, Prince Muhammad Muʿazzam

[Raqaʾim-i Karaʾim, #106]

If you agree with my strategy for ensuring peace and satisfaction—that is, the division of the kingdom after the departure of this frail one [Aurangzeb]—then the only solution is to place your younger son [Aurangzeb’s grandson] in Kabul with a great army and Muhammad Muʿizz al-Din Bahadur37 in Multan with sufficient supplies. All this has been indicated in written testaments [vasaya]. There are many illustrious notables, claimants, and people on both sides38 who would kindle the fires of battle [while striving to acquire power]; in doing so, they commend the state to its grave and consign their lives to bitterness. One such man was Muhammad Dara Shukuh. Had he listened to the advice of His Majesty [Shahjahan] and paid scrupulous attention to His Majesty’s counsel, he would have acted [in a better manner], and there would have been no reason for him to come to such a bad end. After all, the truth [haqq, that is, rightful claim to the throne] was also on his side [bar taraf-i u ham bud]. Greed hounds mankind, granting him not even a moment’s respite.

[Arabic prayer] O God, make the community of Muhammad righteous, and may you be pleased with the community of Muhammad. Peace be upon Him and His family and the companions; praise be to Him at the beginning and at the end; peace [be with you].

POEMS FROM DARA SHUKUH’S DIVAN

Ghazal No. 60

Make my heart joyful, Muslims!

Free yourselves from fetters and restraints.

My heart constricts with sadness from apprenticeship;

For the sake of Truth/God [haqq], make me a master!

Take me beyond all tribes,

Do not remember me again.

I tear my nets to pieces.

How long will you make a hunter of me?

As Qadiri has done, you too destroy all heresy, belief, religious sects

Except for Truth/God.

Ghazal No. 134

The leader [pir] of the wine tavern gave the order for music and dance [samaʿ];

Farewell to all other ascetics [zahidan] besides myself [ma]!

The wine tavern and I [ma], music, dance [samaʿ] and ecstasy [vajd]:

Tell me, then, what’s better than these wares?

The believer and the infidel [muʾmin u kafir] did not accept me;

My truth [haqiqat-am] and heresy [kufr] were in complete agreement [ijmaʿ].

When the sun of certainty rose to its zenith,

The darkness of illusion became illuminated with light.

Heresy and Islam [kufr u islam] became one and the same [yik-san shud];

For Qadiri, then, no dispute remains.

Ghazal No. 174

Captivator of God-fearing hearts,

Leader [sarvar] of the gnostics [ʿarifan] and the lowly;

Heir to the seat of the messenger of the Lord [Muhammad],

Guide, showing the way to those who are lost;

Like Jesus, reviver of those with deadened hearts,

A balm for the wounds of uprooted souls.

That Muhammad [the Prophet] was the king of messengers [shah-i rasulan bud];

This Muhammad [Dara Shukuh] would be king of kings [buvad shah-i shahan]

Qadiri extended his hand to the royal hem [bi daman-i shah];

He is not one of those who fall short [dast-kutahan].

1. For a first-person account of an earlier succession, see Muzaffar Alam and Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Writing the Mughal World: Studies on Culture and Politics (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 123–64.

2. On the active role played by (noble) women in high-level political matters, see Michael H. Fisher, The Mughal Empire (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2016), 18–19, 143–44.

3. For a concise account of these events, see, for instance, Fisher, The Mughal Empire, 182–206; and John F. Richards, The Mughal Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 151–84. The second selection here, an excerpt from the Maasir-i ʿalamgiri, also presents a detailed account of the war of succession.

4. For an example of the former, see Richards, The Mughal Empire, 290; for the latter, see Jadunath Sarkar, History of Aurangzeb Based on Original Sources, 5 vols. (London: Longmans, Green, 1920). For an overview of the “decline” model and its detractors, see Muzaffar Alam, The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India; Meena Bhargava, ed., The Decline of the Mughal Empire (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014); Seema Alavi, ed., The Eighteenth Century in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008); Abhishek Kaicker, Unquiet City: Making and Unmaking Politics in Mughal Delhi, 1707–39 (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2014).

5. Richards, The Mughal Empire, 165–252.

6. See Fisher, The Mughal Empire, 130.

7. Jadunath Sarkar, Anecdotes of Aurangzib (English Translation of Ahkam-i-Alamgiri Ascribed to Hamid-ud-din Khan Bahadur) (Calcutta: M. C. Sarkar & Sons, 1949), 24.

9. Dara Shukuh refers to both Hindus and Muslims (provocatively, but not incorrectly) as muvahhidun, “monotheists.”

10. Dara Shukuh, Majmaʿ al-bahrayn, ed. M. Malfuz-ul-Haq, 1989 (1929), 79. This couplet is from the first section (on monotheism [touhid]) of Sanaʿi’s sufi masnavi, Hadiqat al-haqiqat va shariʿat al-tariqat. As the editor points out, this couplet was also used in an inscription penned by Abul Fazl in Kashmir. Carl Ernst has noted the importance of a significant deviation from Sanaʾi’s original: Dara Shukuh substitutes “islam” for Sanaʾi’s “religion” (“din”), which Ernst says gives the couplet “a political character implying Hindu and Islamic communities or doctrines”; Aurangzeb took this to be clear proof of Dara Shukuh’s heresy. Carl Ernst, “Muslim Studies of Hinduism? A Reconsideration of Arabic and Persian Translations from Indian Languages,” Iranian Studies 36, no. 2 (2003): 187.

11. For an important reevaluation of such received characterizations of Dara Shukuh and his implied ideological opposition to Aurangzeb, see Rajeev Kinra, “Infantilizing Baba Dara: The Cultural Memory of Dara Shekuh and the Mughal Public Sphere,” Journal of Persianate Studies 2 (2009): 165–93. Kinra notes, for instance, that “despite the great admiration in some circles for Dara’s intellect and cultural patronage, there was also a significant, and important, constituency of Hindu an Muslim alike that disliked him for entirely non-sectarian reasons, sometimes having to do with a belief that Dara’s narcissistic arrogance made him unfit for the throne, and sometimes out of pure personal enmity” (168).

12. Many editors (especially the editor of Aurangzeb’s letters, and to a lesser extent Sarkar in his translation of the Maasir) opt for concise paraphrase, shearing historical texts of “extraneous” couplets and prayers and condensing personal letters to their “general gist.” This can be as reductive and misleading as describing the Taj Mahal as simply a mausoleum: filigree and inscriptions may not be what keeps the structure standing, but these ornamental features are by no means merely ancillary to its meaning.

13. From Aqil Khan Razi, Vaqiʿat-i ʿalamgiri of Aqil Khan Razi (An Account of the War of Succession Between the Sons of the Emperor Shah Jahan), ed. Khan Bahadur Maulvi Haji Zafar Hasan (Delhi: Mercantile Printing Press, 1946). 46–50. A slightly different version of this letter is given in Muhammad Salih Kamboh, ʿAmal-i Salih, also known as the Shahjahan-nama al-mousum bi Shahjahan-nama, ed. Ghulam Yazdani and Vahid Qurayshi, vol. 3, no. 4 (Lahur: Majlis-i Taraqqi-yi Adab, 1967–1972), 290–92.

14. Aurangzeb, Raqaʾim-i karaʾim (Epistles of Aurangzeb), collected by Saiyid Ashraf Khan Husaini, ed. S. M. Azizuddin Husain (Delhi: Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli, 1990), 59.

15. Aurangzeb, Raqaʾim-i karaʾi, 81.

16. Dara Shukuh belonged to the Qadiri Sufi order, to which his poetic pen name (takhallus) eponymously refers.

17. His great-grandfather Akbar’s famous policy of “universal peace” or “tolerance for all”; see Fisher, The Mughal Empire, 130.

18. Prince Muhammad Dara Shukuh, Divan-i Dara Shukuh, ed. Ahmad Nabi Khan (Mashhad: Nashr-i Nuvid, 1985), Ghazal 42.

19. Dara Shukuh, Divan-i Dara Shukuh, Ghazal 174.

20. See Muzaffar Alam, “In Search of a Sacred King: Dārā Shukoh and the Yogavāsiṣṭas of Mughal India,” History of Religions 55, no. 4 (May 2016): 429–59.

21. For a detailed discussion of the problems surrounding the definition and translation of the term “haqq,” see William Chittick, The Self-Disclosure of God: Principles of Ibn al-ʿArabi’s Cosmology (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998), xxiv.

22. On the significance of the deliberate homage paid by Shahjahan’s title “sahib-qiran-i sani” (Second Lord of the Auspicious Planetary Conjunction) to Timur, its first bearer (“sahib-qiran”), see A. Azfar Moin, The Millennial Sovereign: Sacred Kingship and Sainthood in Islam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 23 et passim.

23. “Yasfiku d-dimaʾ” is a Qurʾanic phrase from the Surat al-Baqara. In this verse, the angels express consternation at God’s decision to invest humans with temporal authority, objecting (no doubt, quite rightly) that political power wielded by human beings would be a bloody business:

And [mention, O Muhammad], when your Lord said to the angels, “Indeed, I will make upon the earth a successive authority [khalifa].” They [the angels] said, “Will You place upon it one who causes corruption therein and sheds blood, while we declare Your praise and sanctify You?” Allah said, “Indeed, I know that which you do not know.” (Q. 2:30, Sahih International)

24. “Buland-iqbal,” (he whose fortune is great) was an official title given to Dara Shukuh by Shahjahan in one of several public demonstrations of his esteem and preference for his eldest son during the years leading up to the wars of succession. See Fisher, The Mughal Empire, 182 et passim.

25. “Ula al-amri min-kum,” from the Surat al-Nisaʿ; echoing the previous Qurʾanic reference, this verse also attempts to allay any doubts concerning the authority of those in power:

O you who have believed, obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you. And if you disagree over anything, refer it to Allah and the Messenger, if you should believe in Allah and the Last Day. That is the best [way] and best in result. (Q. 4:59, Sahih International)

26. Occasionally, some secondary literature and older translations of Mughal texts provide equivalents for Islamic (hijri) dates using the older, pre-1582 Julian calendar, which lags behind the modern Gregorian calendar during this period by ten days. The date of Dara Shukuh’s execution (the twenty-first of Zi l-hijja, 1069 AH) is therefore sometimes given as August 30, 1659 (Julian), and sometimes September 9, 1659 (Gregorian). All Islamic (hijri) dates here are converted to their Gregorian equivalents. For the history of various calendar systems, see Reza Abdollahi, “Calendars ii. In the Islamic Period,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica; see also M. Athar Ali, F. C. de Blois, et al., “Taʾrikh,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed.

27. This epithet is applied to Dara Shukuh several times throughout the Ma’asir. Typical Persian terms for “heresy” (in the Oxford English Dictionary sense of the term, defined on the basis of Christianity as any “theological or religious opinion or doctrine maintained in opposition…to that of any church, creed, or religious system, considered as orthodox”) include “ilhad” (mentioned in this text), “zandaqa,” “ghuluvv” (exaggeration), “bidʿat” (innovation), and others, many of which have historically specific meanings. The use of “zalalat” here, in the etymologically laden sense of “error, deviation,” has Qurʾanic resonances: words with the root ḍ-l-l appear in many verses, including the Surat al-Fatiha, which closes with an invocation to God to “guide us to the straight path [sirat al-mustaqim] / the path of those upon whom You have bestowed favor, not of those who have evoked [Your] anger or of those who are astray [al-dallina]” (Q. 1:6–7, Sahih International). It is likely that the Ma’asir stresses the heretical leanings of Dara Shukuh in this way to provide sufficient narrative justification for his eventual execution—the official reason for which was heresy. On Dara Shukuh’s trial and execution for heresy, see Craig Davis, “Dara Shukuh and Aurangzib: Issues of Religion and Politics and their Impact on Indo-Muslim Society” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 2002), 29 et passim, for a nuanced reading of the charges leveled against Dara Shukuh in the Ma’asir and the ʿAlamgir-nama.

28. A measure of distance in premodern South Asia, more familiarly known in Hindavi as “kos”; the exact length varies by region, but it is roughly equivalent to one-third of a mile. Compare entries by Hobson-Jobson, 261, and Giyath al-Lughat.

29. The phrase in its entirety, “nasrun min allahi fathun qarib,” is from the Surat al-Saff (Q. 61.13).

30. This is likely a reference to Aurangzeb and Jahanara’s exchange of letters, demonstrating Aurangzeb’s acquiescence to his sister’s suggestion that he formulate his wishes to Shahjahan in writing.

31. Surat al-Nisaʾ (Q. 4:59). Part of this sentence, “uli l-amri min-kum,” was quoted by Jahanara in her letter to Aurangzeb (see Note 24).

32. “Qasab al-sabq-i bar-tar-i” refers to the Arab custom of planting a reed in the ground for which two horsemen race, trying to see who can first tear it out and throw it in front of him. Compare Hans Wehr, A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, 897, and Dehkhoda, “Qasab al-sabq” entry.

33. The “kalima tayyiba,” that is, the shahada, (statement of faith): “La ilaha illa l-lah, Muhammadun rasulu l-lah”: “There is no god except God, Muhammad is the apostle of God.”

34. “Verily is [this] kingdom God’s, he gives it to whomever he wills.” Compare the end of Qurʾan 2:247 (Sahih International): “Wa l-lahu yuʾti mulka-hu man yashaaʾu wa l-lahu wasiʿun ʿalimun” (“And Allah gives His sovereignty to whom He wills. And Allah is all-Encompassing [in favor] and Knowing.”

35. Aurangzeb may have had Akbar’s precedent in mind: in 1584, Akbar introduced the tarikh-i ilahi (divine era), a new calendric system based on the solar year, whose months were taken from the pre-Islamic Persian calendar. The first day of the ilahi year was the Persian festival of Nouruz, and the calendar began with Akbar’s accession. This ideologically potent action of “clearing the calendar” upon accession would not have been lost on Aurangzeb (see M. Athar Ali, “Ilahi Era”, Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed.). Aurangzeb did not abolish the ilahi calendar, but he did try to expunge all of its “un-Islamic” aspects, especially Nouruz.

36. In Goldziher’s definition, ahl-i ahvaʾ is “a term applied by the orthodox theologians to those followers of Islam, whose religious tenets in certain details deviate from the general ordinances of the Sunnite confession” (Goldziher, “Ahl-i Ahwaʾ”, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed.).

37. That is, his son’s other son; this grandson’s birth is mentioned in the Ma’asir..

38. The precise meaning of “both sides” here is ambiguous; he is alluding, perhaps, to his own succession war with his brothers.

FURTHER READING

Alam, Muzaffar. The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India: Awadh and the Punjab 1707–1748, 2nd ed. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Alam, Muzaffar, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam, eds. The Mughal State, 1526–1750. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bernier, Francois. Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656–1668. Translated on the basis of Irving Brock’s version and annotated by Archibald Constable (1891). London: Oxford University Press, 1934.

Bhargava, Meena. ed. The Decline of the Mughal Empire. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Bhimsen, Tarikh-i dilkasha:Memoirs of Bhmisen Relating to Aurangzib’s Deccan Campaigns. Ed. V. G. Khobrekar. Trans. Jadunath Sarkar. Bombay: Department of Archives, Government of Maharashtra, 1972.

Dara Shukuh, Prince Muhammad. Majmaʿ-ul-bahrain, or, The Mingling of the Two Oceans. Ed. M. Mahfuz-ul-Haq. Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1929.

——. Sirr-i-Akbar (Sirr-ul-Asrar): The Oldest Translation of the Upanishads from Sanskrit into Persian by Dara-Shukoh. Ed. Tara Chand and S. M. Reza Jalali Naini. Tehran: Taban Printing Press, 1957.

Dryden, John. Aureng-zebe. Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey, 1994.

Faruqui, Munis D. The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Kamboh, Muhammad Salih. ‘Amal-i-Salih, or Shah Jahan Namah, a Complete History of the Emperor Shah Jahan. Ed. Ghulam Yazdani. 4 vols. Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1923–1946.

Kinra, Rajeev. Writing Self, Writing Empire: Chandar Bhan Brahman and the Cultural World of the Indo-Persian State Secretary. [especially chap. 6]. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015.

Manucci, Niccolao. Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India, 1653–1708. Trans. William Irvine. 4 vols. London: J. Murray, 1906–1908.

Moin, A. Azfar. The Millennial Sovereign: Sacred Kingship and Sainthood in Islam. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Sarkar, Jadunath. Fall of the Mughal Empire. 4 vols. Calcutta: M. C. Sarkar & Sons, 1949.

——. History of Aurangzeb Based on Original Sources. 5 vols. London: Longmans, Green, 1920.