“To the dull mind all nature is leaden. To the illumined mind the whole world burns and sparkles with light.”

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

“Behold, I show you a mystery; We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye…”

—CORINTHIANS 15:51

For as long as I can remember, I’ve always dreamed of having the ability to help people change virtually anything in their lives. Instinctively, at an early age, I realized that to be able to help others change, I had to be able to change myself. Even in junior high school, I began to pursue knowledge through books and tapes that I thought could teach me the fundamentals of how to shift human behavior and emotion.

Of course I wanted to improve certain aspects of my own life: get myself motivated, get myself to follow through and take action, learn how to enjoy life, and learn how to connect and bond with people. I’m not sure why, but somehow I linked pleasure to learning and sharing things that could make a difference in the quality of people’s lives and lead them to appreciate and maybe even love me. As a result, by the time I was in high school, I was known as the “Solutions Man.” If you had a problem, I was the guy to see, and I took great pride in this identity.

The more I learned, the more addicted I became to learning even more. Understanding how to influence human emotion and behavior became an obsession for me. I took a speed-reading class and developed a voracious appetite for books. I read close to 700 books in just a few years, almost all of them in the areas of human development, psychology, influence, and physiological development. I wanted to know anything and everything there was to know about how we can increase the quality of our lives, and tried to immediately apply it to myself as well as share it with other people. But I didn’t stop with books. I became a fanatic for motivational tapes and, while still in high school, saved my money to go to different types of personal development seminars. As you can imagine, it didn’t take long for me to feel like I was hearing nothing but the same messages reworked over and over again. There appeared to be nothing new, and I became a bit jaded.

Just after my twenty-first birthday, though, I was exposed to a series of technologies that could make changes in people’s lives with lightninglike speed: simple technologies like Gestalt therapy, and tools of influence like Ericksonian hypnosis and Neuro-Linguistic Programming. When I saw that these tools could really help people create changes in minutes that previously took months, years, or decades to achieve, I became an evangelist in my approach to them. I decided to commit all of my resources to mastering these technologies. And I didn’t stop there: as soon as I learned something, I applied it immediately.

I’ll never forget my first week of training in Neuro-Linguistic Programming. We learned things like how to eliminate a lifetime phobia in less than an hour—something that through many forms of traditional therapy could take as much as five years or more! On the fifth day, I turned to the psychologists and psychiatrists in the class and said, “Hey, guys, let’s find some phobics and cure them!” They all looked at me like I was crazy. They made it very clear to me that I obviously wasn’t an educated man, that we had to wait until the six-month certification program was completed, go through a testing procedure, and if we were successful, only then would we be ready to use this material!

I wasn’t willing to wait. So I launched my career by appearing on radio and television programs throughout Canada and eventually the United States as well. In each of these, I talked to people about these technologies for creating change and made it clear that if we wanted to change our lives, whether it was a disempowering habit or a phobia that had been controlling us for years, that behavior or that emotional pattern could be changed in a matter of minutes, even though they might have tried to change it for years previously.

Was this a radical concept? You bet. But I passionately argued that all changes are created in a moment. It’s just that most of us wait until certain things happen before we finally decide to make a shift. If we truly understood how the brain worked, I argued, we could stop the endless process of analyzing why things had happened to us, and if we could just simply change what we linked pain and pleasure to, we could just as easily change the way our nervous systems had been conditioned and take charge of our lives immediately. As you can imagine, a young kid with no Ph.D. who was making these controversial claims on the radio didn’t go over very well with some traditionally trained mental-health professionals. A few psychiatrists and psychologists attacked me, some on the air.

So I learned to build my career in changing people on two principles: technology and challenge. I knew I had a superior technology, a superior way of creating change based on crucial understandings of human behavior that most traditional psychologists were not trained in. And I believed that if I challenged myself and the people I worked with enough, I could find a way to turn virtually anything around.

One particular psychiatrist called me a charlatan and a liar and charged that I was making false claims. I challenged this psychiatrist to suspend his pessimism and give me an opportunity to work with one of his patients, someone he hadn’t been able to change after working with her for years. It was a bold move, and at first he did not comply with my request. But after utilizing a little leverage (a technique I’ll cover in the next chapter), I finally got the psychiatrist to let a patient come on her own to one of my free guest events and allow me, in front of the room, to work with her. In fifteen minutes I wiped out the woman’s phobia of snakes—at the time she’d been treated for over seven years by the psychiatrist who attacked me. To say the least, he was amazed. But more importantly, can you imagine the references this created for me and the sense of certainty it gave me about what I could accomplish? I became a wild man! I stormed across the country demonstrating to people how quickly change could occur. I found that no matter where I went, people were initially skeptical. But, as I was able to demonstrate measurable results before their eyes, I was able to get not only their attention and interest but also their willingness to apply what I’d talked about to produce measurable results in their own lives.

Why is it that most people think change takes so long? One reason, obviously, is that most people have tried again and again through willpower to make changes, and failed. The assumption that they then make is that important changes must take a long time and be very difficult to make. In reality, it’s only difficult because most of us don’t know how to change! We don’t have an effective strategy. Willpower by itself is not enough—not if we want to achieve lasting change.

The second reason we don’t change quickly is that in our culture, we have a set of beliefs that prevents us from being able to utilize our own inherent abilities. Culturally, we link negative associations to the idea of instant change. For most, instant change means you never really had a problem at all. If you can change that easily, why didn’t you change a week ago, a month ago, a year ago, and stop complaining?

For example, how quickly could a person recover from the loss of a loved one and begin to feel differently? Physically, they have the capability to do it the next morning. But they don’t. Why? Because we have a set of beliefs in our culture that we need to grieve for a certain period of time. How long do we have to grieve? It all depends upon your own conditioning. Think about this. If the next day after you lost a loved one, you didn’t grieve, wouldn’t that cause a great deal of pain in your life? First, people would immediately believe you didn’t care about the loved one you lost. And, based on cultural conditioning, you might begin to believe that you didn’t care, either. The concept of overcoming death this easily is just too painful. We choose the pain of grieving rather than changing our emotions until we’re satisfied that our rules and cultural standards about what’s appropriate have been met.

There are, in fact, cultures where people celebrate when someone dies! Why? They believe that God always knows the right time for us to leave the earth, and that death is graduation. They also believe that if you were to grieve about someone’s death, you would be indicating nothing but your own lack of understanding of life, and you would be demonstrating your own selfishness. Since this person has gone on to a better place, you’re feeling sorry for no one but yourself. They link pleasure to death, and pain to grieving, so grief is not a part of their culture. I’m not saying that grief is bad or wrong. I’m just saying that we need to realize it’s based upon our beliefs that pain takes a long time to recover from.

As I spoke from coast to coast, I kept encouraging people to make life-changing shifts, often in thirty minutes or less. There was no doubt I created controversy, and the more successes I had, the more assured and intense I became as well. To tell the truth, I was occasionally confrontational and more than a little cocky. I started out doing private therapy, helping people turn things around, and then began to do seminars. Within a few short years, I was traveling on the road three weeks out of four, constantly pushing myself and giving my all as I worked to extend my ability to positively impact the largest number of people I could in the shortest period of time. The results I produced became somewhat legendary. Eventually the psychiatrists and psychologists stopped attacking and actually became interested in learning my techniques for use with their own patients. At the same time, my attitudes changed and I became more balanced. But I never lost my passion for wanting to help as many people as I could.

One day about four and a half years ago, not long after Unlimited Power was first published, I was signing books after giving one of my business seminars in San Francisco. All the while I was reflecting on the incredible rewards that had come from following through on the commitments I had made to myself while still in high school: the commitments to grow, expand, contribute, and thereby make a difference. I realized as each smiling face came forward how deeply grateful I was to have developed skills that can make a difference in helping people to change virtually anything in their lives.

As the last group of people finally began to disperse, one man approached me and asked, “Do you recognize me?” Having seen literally thousands of people in that month alone, I had to admit that I didn’t. He said, “Think about it for a second.” After looking at him for a few moments, suddenly it clicked. I said, “New York City, right?” He said, “That’s true.” I said, “I did some private work with you in helping you to wipe out your smoking habit.” He nodded again. I said, “Wow, that was years ago! How are you doing?” He reached in his pocket, pulled out a package of Marlboros, pointed at me with an accusing look on his face and said, ’You failed!” Then he launched into a tirade about my inability to “program” him effectively.

I have to admit I was rattled! After all, I had built my career on my absolute willingness to put myself on the line, on my total commitment to challenging myself and other people, on my dedication to trying anything in order to create lasting and effective change with lightning-like speed. As this man continued to berate my ineffectiveness in “curing” his smoking habit, I wondered what could have gone wrong. Could it be that my ego had outgrown my true level of capability and skill? Gradually I began to ask myself better questions: What could I learn from this situation? What was really going on here?

“What happened after we worked together?” I asked him, expecting to hear that he had resumed smoking a week or so after the therapy. It turned out that he’d stopped smoking for two and a half years, after I’d worked with him for less than an hour! But one day he took a puff, and now he was back to his four-pack-a-day habit, plainly blaming me because the change had not endured.

Then it hit me: this man was not being completely unreasonable. After all, I had been teaching something called Neuro-Linguistic Programming. Think about the word “programming.” It suggests that you could come to me, I would program you, and then everything would be fine. You wouldn’t have to do anything! Out of my desire to help people at the deepest level, I’d made the very mistake that I saw other leaders in the personal development industry make: I had begun to take responsibility for other people’s changes.

That day, I realized I had inadvertently placed the responsibility with the wrong person—me—and that this man, or any one of the other thousands of people I’d worked with, could easily go back to their old behaviors if they ran into a difficult enough challenge because they saw me as the person responsible for their change. If things didn’t work out, they could just conveniently blame somebody else. They had no personal responsibility, and therefore, no pain if they didn’t follow through on the new behavior.

As a result of this new perspective, I decided to change the metaphor for what I do. I stopped using the word “programming” because while I continue to use many NLP techniques, I believe it’s inaccurate. A better metaphor for long-term change is conditioning. This was solidified for me when, a few days later, my wife brought in a piano tuner for our new baby grand. This man was a true craftsman. He worked on every string in that piano for literally hours and hours, stretching each one to just the right level of tension to create the perfect vibration. At the end of the day, the piano played magnificently. When I asked him how much I owed, he said, “Don’t worry, I’ll drop off a bill on my next visit.” My response was, “Next visit? What do you mean?” He said, “I’ll be back tomorrow, and then I’ll come back once a week for the next month. Then I’ll return every three months for the rest of the year, only because you live by the ocean.”

I said, “What are you talking about? Didn’t you already make all the adjustments on the piano? Isn’t it set up properly?” He said, “Yes, but these strings are strong; to keep them at the perfect level of tension, we’ve got to condition them to stay at this level. I’ve got to come back and re-tighten them on a regular basis until the wire is trained to stay at this level.” I thought, “What a business this guy has!” But I also got a great lesson that day.

This is exactly what we have to do if we’re going to succeed in creating long-term change. Once we effect a change, we should reinforce it immediately. Then, we have to condition our nervous systems to succeed not just once, but consistently. You wouldn’t go to an aerobics class just one time and say, “Okay, now I’ve got a great body and I’ll be healthy for life!” The same is true of your emotions and behavior. We’ve got to condition ourselves for success, for love, for breaking through our fears. And through that conditioning, we can develop patterns that automatically lead us to consistent, lifelong success.

We need to remember that pain and pleasure shape all our behaviors, and that pain and pleasure can change our behaviors. Conditioning requires that we understand how to use pain and pleasure. What you’re going to learn in the next chapter is the science that I’ve developed to create any change you want in your life. I call it the Science of Neuro-Associative Conditioning™, or NAC. What is it? NAC is a step-by-step process that can condition your nervous system to associate pleasure to those things you want to continuously move toward and pain to those things you need to avoid in order to succeed consistently in your life without constant effort or willpower. Remember, it’s the feelings that we’ve been conditioned to associate in our nervous systems—our neuro-associations—that determine our emotions and our behavior.

When we take control of our neuro-associations, we take control of our lives. This chapter will show you how to condition your neuro-associations so that you are empowered to take action and produce the results you’ve always dreamed of. It’s designed to give you the kNACk of creating consistent and lasting change.

“Things do not change; we change.”

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU

What are the two changes everyone wants in life? Isn’t it true that we all want to change either 1) how we feel about things or 2) our behaviors? If a person has been through a tragedy—they were abused as a child, they were raped, lost a loved one, are lacking in self-esteem—this person clearly will remain in pain until the sensations they link to themselves, these events, or situations are changed. Likewise, if a person overeats, drinks, smokes, or takes drugs, they have a set of behaviors that must change. The only way this can happen is by linking pain to the old behavior and pleasure to a new behavior.

This sounds so simple, but what I’ve found is that in order for us to be able to create true change—change that lasts—we need to develop a specific system for utilizing any techniques you and I learn to create change, and there are many. Every day I’m picking up new skills and new technologies from a variety of sciences. I continue to use many of the NLP and Ericksonian techniques that I began my career with; some of them are the finest available. Yet I always come back to utilizing them within the framework of the same six fundamental steps that the science of NAC represents. I created NAC as a way to use any technology for change. What NAC really provides is a specific syntax—an order and sequence—of ways to use any set of skills to create long-term change.

I’m sure you recall that in the first chapter I said that one of the key components of creating long-term change is a shift in beliefs. The first belief we must have if we’re going to create change quickly is that we can change now. Again, most people in our society have unconsciously linked a lot of pain to the idea of being able to change quickly. On one hand, we desire to change quickly, and on the other, our cultural programming teaches us that to change quickly means that maybe we never even had a problem at all. Maybe we were just faking it or being lazy. We must adopt the belief that we can change in a moment. After all, if you can create a problem in a moment, you should be able to create a solution, too! You and I both know that when people finally do change, they do it in a moment, don’t they? There’s an instant when the change occurs. Why not make that instant now? Usually it’s the getting ready to change that takes people time. We’ve all heard the joke:

Q: How many psychiatrists does it take to change a lightbulb?

A: Just one… but it’s very expensive, it takes a long time, and the lightbulb has to want to change.

Garbage! You and I have to get ourselves ready to change. You and I have to become our own counselors and master our own lives.

The second belief that you and I must have if we’re going to create long-term change is that we’re responsible for our own change, not anyone else. In fact, there are three specific beliefs about responsibility that a person must have if they’re going to create long-term change:

1) First, we must believe, “Something must change”—not that it should change, not that it could or ought to, but that it absolutely must. So often I hear people say, “This weight should come off,” “Procrastinating is a lousy habit,” “My relationships should be better.” But you know, we can “should” all over ourselves, and our life still won’t change! It’s only when something becomes a must that we begin the process of truly doing what’s necessary to shift the quality of our lives.

2) Second, we must not only believe that things must change, but we must believe, “I must change it.” We must see ourselves as the source of the change. Otherwise, we’ll always be looking for someone else to make the changes for us, and we’ll always have someone else to blame when it doesn’t work out. We must be the source of our change if our change is going to last.

3) Third, we have to believe, “I can change it.” Without believing that it’s possible for us to change, as we’ve already discussed in the last chapter, we stand no chance of carrying through on our desires.

Without these three core beliefs, I can assure you that any change you make stands a good chance of being only temporary. Please don’t misunderstand me—it’s always smart to get a great coach (an expert, a therapist, a counselor, someone who’s already produced these results for many other people) to support you in taking the proper steps to conquer your phobia or quit smoking or lose weight. But in the end, you have to be the source of your change.

The interaction I had with the relapsed smoker that day triggered me to ask new questions of myself about the sources of change. Why was I so effective throughout the years? What had set me apart from others who’d tried to help these same people who had equal intention but were unable to produce the result? And when I’d tried to create a change in someone and failed, what had happened then? What had prevented me from producing the change that I was really committed to helping this person make?

Then I began to ask larger questions, like “What really makes change happen in any form of therapy?” All therapies work some of the time, and all forms of therapy fail to work at other times. I also began to notice two other interesting things: some people went to therapists I didn’t think were particularly skilled, and still managed to make their desired change in a very short period of time in spite of the therapist. I also saw other people who went to therapists I considered excellent, yet were not helped to produce the results they wanted in the short term.

After a few years of witnessing thousands of transformations and looking for the common denominator, finally it hit me: we can analyze our problems for years, but nothing changes until we change the sensations we link to an experience in our nervous system, and we have the capacity to do this quickly and powerfully if we understand…

What a magnificent gift we were born with! I’ve learned that our brains can help us accomplish virtually anything we desire. The brain’s capacity is nearly unfathomable. Most of us know little about how it works, so let’s briefly focus upon this unparalleled vessel of power and how we can condition it to consistently produce the results we want in our lives.

Realize that your brain eagerly awaits your every command, ready to carry out anything you ask of it. All it requires is a small amount of fuel: the oxygen in your blood and a little glucose. In terms of its intricacy and power, the brain defies even our greatest modern computer technology. It is capable of processing up to 30 billion bits of information per second and it boasts the equivalent of 6,000 miles of wiring and cabling. Typically the human nervous system contains about 28 billion neurons (nerve cells designed to conduct impulses). Without neurons, our nervous systems would be unable to interpret the information we receive through our sense organs, unable to convey it to the brain and unable to carry out instructions from the brain as to what to do. Each of these neurons is a tiny, self-contained computer capable of processing about one million bits of information.

These neurons act independently, but they also communicate with other neurons through an amazing network of 100,000 miles of nerve fibers. The power of your brain to process information is staggering, especially when you consider that a computer—even the fastest computer—can make connections only one at a time. By contrast, a reaction in one neuron can spread to hundreds of thousands of others in a span of less than 20 milliseconds. To give you perspective, that’s about ten times less than it takes for your eye to blink.

A neuron takes a million times longer to send a signal than a typical computer switch, yet the brain can recognize a familiar face in less than a second—a feat beyond the ability of the most powerful computers. The brain achieves this speed because, unlike the step-by-step computer, its billions of neurons can all attack a problem simultaneously.

So with all this immense power at our disposal, why can’t we get ourselves to jeel happy consistently? Why can’t we change a behavior like smoking or drinking, overeating or procrastinating? Why can’t we immediately shake off depression, break through our frustration, and feel joyous every day of our lives? We can! Each of us has at our disposal the most incredible computer on the planet, but unfortunately no one gave us an owner’s manual. Most of us have no idea how our brains really work, so we attempt to think our way into a change when, in reality, our behavior is rooted in our nervous systems in the form of physical connections—neural connections—or what I call neuro-associations.

Great breakthroughs in our ability to understand the human mind are now available because of a marriage between two widely different fields: neuro-biology (the study of how the brain works) and computer science. The integration of these sciences has created the discipline of neuro-science.

Neuro-scientists study how neuro-associations occur and have discovered that neurons are constantly sending electro-chemical messages back and forth across neural pathways, not unlike traffic on a busy thoroughfare. This communication is happening all at once, each idea or memory moving along its own path while literally billions of other impulses are traveling in individual directions. This arrangement enables us to hopscotch mentally from memories of the piney smell of an evergreen forest after a rain, to the haunting melody of a favorite Broadway musical, to painstakingly detailed plans of an evening with a loved one, to the exquisite size and texture of a newborn baby’s thumb.

Not only does this complex system allow us to enjoy the beauty of our world, it also helps us to survive in it. Each time we experience a significant amount of pain or pleasure, our brains search for the cause and record it in our nervous systems to enable us to make better decisions about what to do in the future. For example, without a neuro-association in your brain to remind you that sticking your hand into an open flame would burn you, you could conceivably make this mistake again and again until your hand is severely burned. Thus, neuro-associations quickly provide our brains with the signals that help us to re-access our memories and safely maneuver us through our lives.

“To the dull mind all nature is leaden. To the illumined mind the whole world burns and sparkles with light.”

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

When we do something for the first time, we create a physical connection, a thin neural strand that allows us to re-access that emotion or behavior again in the future. Think of it this way: each time we repeat the behavior, the connection strengthens. We add another strand to our neural connection. With enough repetitions and emotional intensity, we can add many strands simultaneously, increasing the tensile strength of this emotional or behavioral pattern until eventually we have a “trunk line” to this behavior or feeling. This is when we find ourselves compelled to feel these feelings or behave in this way consistently. In other words, this connection becomes what I’ve already labeled a neural “super-highway” that will take us down an automatic and consistent route of behavior.

This neuro-association is a biological reality—it’s physical. Again, this is why thinking our way into a change is usually ineffective; our neuro-associations are a survival tool and they are secured in our nervous systems as physical connections rather than as intangible “memories.” Michael Merzenich of the University of California, San Francisco, has scientifically proven that the more we indulge in any pattern of behavior, the stronger that pattern becomes.

Merzenich mapped the specific areas in a monkey’s brain that were activated when a certain finger in the monkey’s hand was touched. He then trained one monkey to use this finger predominantly in order to earn its food. When Merzenich remapped the touch-activated areas in the monkey’s brain, he found that the area responding to the signals from that finger’s additional use had expanded in size nearly 600 percent! Now the monkey continued the behavior even when he was no longer rewarded because the neural pathway was so strongly established.

An illustration of this in human behavior might be that of a person who no longer enjoys smoking but still feels a compulsion to do so. Why would this be the case? This person is physically “wired” to smoke. This explains why you may have found it difficult to create a change in your emotional patterns or behaviors in the past. You didn’t merely “have a habit”—you had created a network of strong neuro-associations within your nervous system.

We unconsciously develop these neuro-associations by allowing ourselves to indulge in emotions or behaviors on a consistent basis. Each time you indulge in the emotion of anger or the behavior of yelling at a loved one, you reinforce the neural connection and increase the likelihood that you’ll do it again. The good news is this: research has also shown that when the monkey was forced to stop using this finger, the area of the brain where these neural connections were made actually began to shrink in size, and therefore the neuro-association weakened.

This is good news for those who want to change their habits! If you’ll just stop indulging in a particular behavior or emotion long enough, if you just interrupt your pattern of using the old pathway for a long enough period of time, the neural connection will weaken and atrophy. Thus the disempowering emotional pattern or behavior disappears with it. We should remember this also means that if you don’t use your passion it’s going to dwindle. Remember: courage, unused, diminishes. Commitment, unexercised, wanes. Love, unshared, dissipates.

“It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well”

—RENE DESCARTES

What the science of Neuro-Associative Conditioning offers is six steps that are specifically designed to change behavior by breaking patterns that disempower you. But first, we must understand how the brain makes a neuro-association in the first place. Any time you experience significant amounts of pain or pleasure, your brain immediately searches for the cause. It uses the following three criteria.

1. Your brain looks for something that appears to be unique. To narrow down the likely causes, the brain tries to distinguish something that is unusual to the circumstance. It seems logical that if you’re having unusual feelings, there must be an unusual cause.

2. Your brain looks for something that seems to be happening simultaneously. This is known in psychology circles as the Law of Recency. Doesn’t it make sense that what occurs in the moment (or close proximity to it) of intense pleasure or pain is probably the cause of that sensation?

3. Your brain looks for consistency. If you’re feeling pain or pleasure, your brain begins to immediately notice what around you is unique and is happening simultaneously. If the element that meets these two criteria also seems to occur consistently whenever you feel this pain or pleasure, then you can be sure that your brain will determine that it is the cause. The challenge in this, of course, is that when we feel enough pain or pleasure, we tend to generalize about consistency. I’m sure you’ve had someone say to you, “You always do that,” after you’ve done something for the first time. Perhaps you’ve even said it yourself.

Because the three criteria for forming neuro-associations are so imprecise, it is very easy to fall prey to misinterpretations and create what I call false neuro-associations. That’s why we must evaluate linkages before they become a part of our unconscious decision-making process. So often we blame the wrong cause, and thereby close ourselves off from possible solutions. I once knew a woman, a very successful artist, who hadn’t had a relationship with a man for twelve years. Now, this woman was extremely passionate about everything she did; it’s what made her such a great artist. However, when her relationship ended and she found herself in massive pain, her brain immediately searched for the cause—it searched for something that was unique to this relationship.

Her brain noted that the relationship had been especially passionate. Instead of identifying it as one of the beautiful parts of the relationship, she began to think that this was the reason that the relationship ended. Her brain also looked for something that was simultaneous to the pain; again it noted that there had been a great deal of passion right before it had ended. When she looked for something that was consistent, again passion was pinpointed as the culprit. Because passion met all three criteria, her brain decided that it must be the reason the relationship ended painfully.

Having linked this as the cause, she resolved never to feel that level of passion in a relationship again. This is a classic example of a false neuro-association. She had linked up a false cause, and this was now guiding her current behaviors and crippling the potential for a better relationship in the future. The real culprit in her relationship was that she and her partner had different values and rules. But because she linked pain to her passion, she avoided it at all costs, not only in relationships, but even in her art. The quality of her entire life began to suffer. This is a perfect example of the strange ways in which we sometimes wire ourselves; you and I must understand how our brain makes associations and question many of those connections that we’ve just accepted that may be limiting our lives. Otherwise, in our personal and professional lives, we are destined to feel unfulfilled and frustrated.

Even more insidious are mixed neuro-associations, the classic source of self-sabotage. If you’ve ever found yourself starting to accomplish something, and then destroying it, mixed neuro-associations are usually the culprit. Perhaps your business has been moving in fits and starts, flourishing one day and floundering the next. What is this all about? It’s a case of associating both pain and pleasure to the same situation.

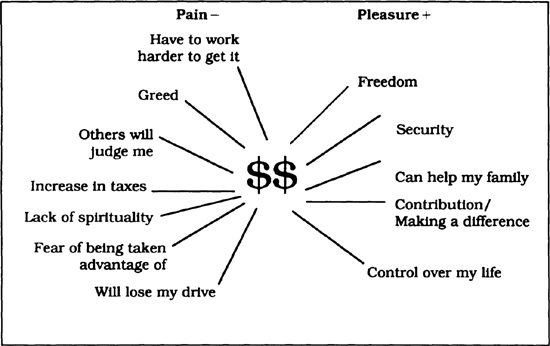

One example a lot of us can relate to is money. In our culture, people have incredibly mixed associations to wealth. There’s no doubt that people want money. They think it would provide them with more freedom, more security, a chance to contribute, a chance to travel, to learn, to expand, to make a difference. But simultaneously, most people never climb above a certain earnings plateau because deep down they associate having “excess” money to a lot of negatives. They associate it to greed, to being judged, to stress, with immorality or a lack of spirituality.

One of the first exercises I ask people to do in my Financial Destiny™ seminars is to brainstorm all the positive associations they have to wealth, as well as all the negative ones. On the plus side they write down such things as: freedom, luxury, contribution, happiness, security, travel, opportunity, and making a difference. But on the minus side (which is usually more full) they write down such things as: fights with spouse, stress, guilt, sleepless nights, intense effort, greed, shallowness, and complacency, being judged, and taxes. Do you notice a difference in intensity between the two sets of neuro-associations? Which do you think plays a stronger role in their lives?

When you’re deciding what to do, if your brain doesn’t have a clear signal of what equals pain and what equals pleasure, it goes into overload and becomes confused. As a result, you lose momentum and the power to take the decisive actions that could give you what you want. When you give your brain mixed messages, you’re going to get mixed results. Think of your brain’s decision-making process as being like a scale: “If I were to do this, would it mean pain or pleasure?” And remember, it’s not just the number of factors on each side but the weight they individually carry. It’s possible that you could have more pleasurable than painful associations about money, but if just one of the negative associations is very intense, then that false neuro-association can wipe out your ability to succeed financially.

What happens when you get to a point where you feel that you’re going to have pain no matter what you do? I call this the pain-pain barrier. Often, when this occurs, we become immobilized—we don’t know what to do. Usually we choose what we believe will be the least painful alternative. Some people, however, allow this pain to overwhelm them completely and they experience learned helplessness.

Using the six steps of NAC will help you to interrupt these disempowering patterns. You will create alternative pathways so that you’re not just “wishing” away an undesired behavior, or overriding it in the short term, but are actually rewiring yourself to feel and behave consistent with your new, empowering choices. Without changing what you link pain and pleasure to in your nervous system, no change will last.

After you read and understand the following six steps, I challenge you to choose something that you want to change in your life right now. Take action and follow through with each of the steps you’re about to learn so that you not only read the chapter, but you produce changes as the result of reading it. Let’s begin to learn…