1

FAMILY

If you come to live with me you shall never want a shilling in your pocket, a gun to fowl, a horse to ride, or a whore.

ARTHUR ANNESLEY, fourth Baron Altham, n.d.1

At the time of his abduction, Jemmy Annesley was the putative heir to one of the greatest family fortunes in Ireland. Other than his father’s properties and peerage, he stood to receive extensive estates in Ireland, England, and Wales as well as four aristocratic titles, including the treasured earldom of Anglesea, one of two English peerages. By one estimate, the annual income from the lands approached the princely sum of £10,000, roughly comparable in today’s prices to more than £1,000,000. By contrast, in Stevenson’s Kidnapped, set in Scotland in the year 1751, the young protagonist, David Balfour, is due to inherit, following his father’s death, no more than an estate west of Edinburgh that includes the house of Shaws, a large but decrepit mansion.2

Just a century earlier in Ireland, the Annesleys had been newcomers—aspiring Englishmen with neither titles nor substantial riches. Apart from personal tenacity and ambition, their rise owed much to Ireland’s dramatically transformed social order. Following a new wave of Elizabethan conquest in the late sixteenth century, Protestant adventurers laid claim to confiscated estates, displacing the native Irish with English and Scottish tenants. Colonization, the English monarchy hoped, promised to relieve Britain of its impoverished masses and subdue the indigenous Catholic population—“that rude and barbarous nation,” remarked Elizabeth.3

In the “plantation” of Munster in southwestern Ireland, among the thirty-five grantees, or “undertakers,” seeking to better their fortunes was an army officer fresh from the fighting, Captain Robert Annesley of Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire. The younger son of a gentry family, he obtained in 1589, at thirty years of age, 2,600 acres in County Limerick. The grant was smaller than most. Another military man, Sir Walter Raleigh, a courtier, topped the beneficiaries with 42,000 acres in Cork and Waterford. But Annesley’s tract was a start, and, for an ambitious squire, a promising one.4

Greater glory awaited his son Francis, a favorite of James I, who became vice-treasurer of Ireland in 1625 and the recipient of two Irish titles: Baron Mountnorris, for the fort of Mountnorris that he had garnered in County Armagh, and Viscount Valentia, after an island once allegedly settled by the Spanish off Ireland’s southwestern coast. Those honors, however, paled next to the achievements of Arthur, his eldest son. After serving in the English House of Commons for a brief period during the Civil War, Arthur helped to choreograph the return in 1660 of Charles II. For his loyalty, he became not only a privy counsillor but also an English peer, the first Earl of Anglesea as well as Baron Newport Pagnell. Displaying a shrewd aptitude for political advancement, he was appointed lord privy seal in 1673, a traditional font of patronage.5

Already one of Ireland’s most powerful men, Arthur became, with the acquisition of fresh estates, one of its largest landowners. He was a figure of considerable learning and culture, adopting the motto, from Horace, of Virtutis Amore (With Love of Virtue) for the family’s coat of arms. Dinner guests at his London mansion in Drury Lane, lying just south of St-Giles-in-the-Fields, included the likes of John Locke and the Earl of Salisbury. A patron of the poet Andrew Marvell, the earl boasted the largest private library in England, some thirty thousand volumes, which he regularly consulted until his death from quinsy, a severe inflammation of the throat, in 1686.6

John Michael Wright, Arthur Annesley, 1st Earl of Anglesey, 1676.

Such were the heights attained by the house of Annesley over just three generations. Along with other “New English” families arriving after the Reformation, the Annesleys were charter members of Ireland’s Protestant Ascendancy, the Anglo-Irish elite that dominated the kingdom until the nineteenth century. Fundamental to the family’s success was its deepening involvement in court politics, coupled with a willingness to subordinate political principles and personal loyalties in pursuit of preferment and private gain. Although they were not men devoid of convictions, neither religion nor ideology hampered their quest. According to his diary, the Earl of Anglesea was a devout Calvinist, though he attended Anglican services, occasionally with the king. Nor did his nonconformist beliefs prevent the marriages of two of his daughters to prominent Irish Catholic nobles. Above all, the Annesleys, as responsible aristocrats, remained committed to furthering the family’s fortunes. Eager to establish titled households in both Ireland and England, Anglesea persuaded the king in 1673 to create an Irish barony for Altham, his second son. In the meantime, his eldest son, James, stood poised to inherit not only his father’s English and Irish titles but also the bulk of his estates, which, one observer later claimed, “far exceed any other” in Ireland.7

Annesley Coat of Arms, n.d. The crest displays a shield bordered by a Roman centurion on the left and a Moorish prince, a popular heraldic symbol, on the right. The profile of a Moor’s head crowns the shield, beneath which is the maxim Virtutis Amore (With Love of Virtue).

If the Annesleys spent much of the seventeenth century advancing their fortunes, only the rapidity and scale of their ascent set them apart. After all, the Ascendancy was an imported Protestant elite imposed upon a predominantly Catholic population; in no sense was it a traditional aristocracy animated by an ancestral attachment to its lands. By the 1700s, only a small remnant of the leading families possessed either Old Gaelic or Old English roots (originating before the reign of Henry VIII). Most eighteenth-century grandees descended from families who had arrived in Ireland between the 1530s and the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642. With conquest and colonization came the elimination of ancient peerages, if not by the mid-seventeenth century then in the aftermath of the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, in which a larger Protestant army under William III defeated Irish and French forces commanded by James II, prompting Catholic Jacobite families, such as the Dillons, MacCarthys, and O’Briens, to begin leaving the country. The few remaining Catholic peers were forbidden to sit in the House of Lords, and by 1749, only six “Popish” lords, like the Earl of Westmeath and Viscount Mountgarrett, still resided in the kingdom.8

The influx of Protestant adventurers resulted, during the early Stuart monarchies, in a rapid inflation of fresh titles available from the Crown. A sizable number were put up for sale, regardless of the buyer’s personal qualifications. Whereas an English barony during the reign of James I cost as much as £10,000, an Irish title could be had for £1,500. More than two-thirds of new Irish peers bore no prior connection to the island, including some with no interest in ever residing there. One aspiring earl, Sir William Pope, could not decide the best town in Ireland for the name of his title. Having narrowed the choice to Granard or Lucan, he received a letter from his puzzled son: “[I] am certain that there is such towns as Lucan and Granard, but can not find it in the map.…If it is possible, we will change Granard for a whole county.” For his troubles, along with the sum of £2,744, Pope in 1628 took the name of an Ulster county and became the Earl of Downe.9

Although the Irish peerage during the eighteenth century was small, with slightly more than one hundred members, its recent origins had resulted in considerable fluidity. For many Protestant nobles, their primary identification with Ireland was one of material fulfillment and social advancement. Often, in fact, the wealthiest peers became absentee landlords, with titles and estates not just in Ireland but also in England. In 1704, at age twenty-one, John Perceval, the future Earl of Egmont, inherited 22,000 acres of land in Cork and Tipperary but spent the bulk of his life in London. As late as the 1720s, from one-sixth to one-fourth of Irish rents was annually remitted to absentees. In England, these lords intermarried with privileged families, only returning to their Irish estates for short spells.10

By contrast, the island’s resident peerage, along with greater numbers of knights and squires, lacked the cultivated gentility of England’s aristocracy. Like the American colonies, Ireland remained a borderland of the British Empire; the advance of metropolitan manners and values, even in Dublin, progressed slowly. “Till their situation or their manners are altered,” wrote John Boyle, fifth Earl of Orrery, an English native with extensive lands in Ireland, “I hope it will not be my ill fortune to live amongst them.” 11

Absent from the upper ranks was a strong sense of self-discipline; excess and intemperance set the standard. Cards and gaming, cockfights, hurling matches, and hunting parties filled idle hours. “A kennel of dogs is the summum bonum of many a rural squire,” wrote “Hibernicus” in the Dublin Weekly Journal. Entertainments were extravagant. Sumptuous dinners, larded with rumps of beef and saddles of venison, flowed with claret and whiskey punch. “The whole business of the day,” an essayist complained in 1729, “is to course down a hare, or some other worthy purchase; to get over a most enormous and immoderate dinner; and guzzle down a proportionable quantity of wine.” 12

Still, their improvidence masked a deeper insecurity. A visiting Englishman hinted as much in describing dinner parties: “They always praise the dishes at their own tables and expect that the company should spare no words in their commendation.” Another traveler commented upon the vanity of grandees “even from indifferent families.” 13

Many wellsprings fed the insecurity of the Irish aristocracy, including its ambivalent status within both Ireland and the empire. First and foremost, members of the Ascendancy preened themselves as loyal Englishmen, tied by language and law, faith, and blood to the land of their ancestors. In an essay intended for an English audience, Francis Annesley, an influential member of the Irish House of Commons, declared in 1698 that his fellow Protestants were “Englishmen sent over to conquer Ireland, your countrymen, your brothers, your sons, your relations, your acquaintance.” And yet, time and again the English parliament enacted legislation counter to Irish interests. Widespread poverty and economic instability only added to the elite’s want of self-confidence, as did the country’s turbulent heritage. In 1725, a Dublin newspaper reflected, “To be born in IRELAND is usually looked upon as a misfortune.” English commentators lost few opportunities to lampoon Irish “backwardness.” Jestbooks like Bogg-Witticisms, first published in 1682, popularized the comic figure of “Teague” (an English corruption of the Gaelic name Tadhg), a favorite target for years to come on the London stage. Of absentee landlords, a Dublin writer moaned “that many of our gentlemen bring home with them a scorn for our poverty and obscurity.” 14

Long after the last spasms of rebellion and conquest, brute force remained central to the Ascendancy character, not unlike the propensity for bloodshed characteristic of the English aristocracy during much of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. “Their long intestine wars, their constant and slavish dependence upon another kingdom, and their just dread of popery are some sort of excuses for the fire of their brains and the fury of their hearts,” observed Orrery.15

Quick to take offense, Protestant gentlemen in Ireland routinely dangled swords at their sides, whether in town or in the country. Nor was it uncommon for a neighborhood feud to end in violence. Gentry sons grew notorious for abducting young heiresses to wed and ravish at the point of a sword. Few of the perpetrators were prosecuted, much less punished. Indeed, laws often went unenforced owing to the connivance of landed magnates. Always vulnerable to abuse were social inferiors. Overcharged at a Cork inn for wine, a young Englishman gave the waiter a “hearty drubbing.” “It is some satisfaction in this country,” he marveled, “that a man has it in his power to punish, with his own hand, the insolence of the lower class of people, without being afraid of a crown-office[r], or a process at law.” 16

Dueling was the most obvious manifestation of this violent ethos. At a time when upper-class violence in England had given way to litigation as the preferred mode of combat, duels remained customary, especially in Dublin. Then, too, many adversaries fought not to uphold personal honor but to exact retribution. These were not set pieces of ritualized violence but bloody clashes more often waged on the spot with short swords than with pistols at a dignified distance. A County Cork combatant in 1733 was stabbed in the back as he lay floundering in the grass. Rarely was eighteenth-century etiquette observed or quarter shown. At a private party, two gentlemen fired pistols at one another in a bedchamber. “It is safer to kill a man, than steal a sheep or a cow,” complained Dr. Samuel Madden, the author of Reflections and Resolutions Proper for the Gentlemen of Ireland…(1738). 17

The first obligation of every aristocrat, instilled from childhood, was to transfer to the succeeding generation his titles and estates in a condition equal if not superior to that in which they had been received. The head of a noble house more nearly resembled a caretaker or trustee than a proprietor free to dispose of his property at will. Estates were not to be squandered or sold, but kept intact and improved to preserve family continuity. To do otherwise, owing to improvidence or negligence, was an act of betrayal to the line. As Lord Delvin, a County Westmeath grandee, observed, it was “a glorious thing to save an estate for a family, and eternize your name.” 18

Just as critical to the family, of course, was a sufficient supply of male heirs to keep the house and its honors from extinction. The Gaelic tradition of partible inheritance had been one in which estates were divided among male descendants; but upon Ireland’s conquest, primogeniture in tail male, whereby titles and the bulk of one’s property fell to the eldest son, became the established system in order to protect estates from subdivision and dispersion. With infant mortality a persistent danger, most families, nonetheless, favored an adequate number of sons—“an heir and a spare,” as the saying went. The more the better, in fact, so long as each understood his place in the chain of succession. The eldest son, in turn, was expected to provide lands for his male siblings until each had entered a profession.19

By any measure—honor, wealth, power—the first generations of Annesleys laid a formidable foundation both in Ireland and England for the family’s future success. No aristocratic house could have expected more from its forebears. Equally important, there was no apparent shortage of male heirs. In fact, besides James and Altham, the Earl of Anglesea and his wife were blessed with four additional boys, only one of whom died in infancy. By the close of the 1600s, James, who had become second Earl of Anglesea on his father’s death, had sired three sons of his own.20

All the same, it was the fortunate family that could sustain a direct line of male descent over several generations. The demographic vagaries of life, marriage, and death, even in the best of times, posed a continual threat to family continuity. As fate would have it, the period from 1650 to 1740 in Britain was one of declining marital fertility and rising mortality. Precise reasons are hard to find, though heightened exposure to diseases, via shipping from the New World, Africa, and Asia, might help to explain the mounting toll of deaths.21

Among the Annesleys, early signs of trouble arose soon enough within the households of James’s three sons, the family’s fifth Irish generation. Born in 1670, the eldest, also named James, became third Earl of Anglesea and fourth Viscount Valentia on his father’s precipitous death in 1690. At thirty years of age, he wed Lady Catharine Darnley, the illegitimate daughter of James II, well known for her prickly disposition. The unhappy couple had one daughter. Shortly before the earl died from consumption in 1702, Catharine claimed to the English House of Lords that he had tried to murder her.22

Waiting in the wings was John, who acquired his elder brother’s titles and most of his property. Although married, he, too, fathered no children other than a single daughter before his own death in 1710. That left the all-important business of producing an heir to the family’s lands and titles to the youngest of the three brothers, Arthur (b. 1678), who now became fifth Earl of Anglesea and sixth Viscount Valentia, with an annual income estimated at £6,000 from his Irish estates alone, which in County Wexford approached 20,000 acres. Already a leading Tory politician with influence both in Dublin and London, he had been a gentleman of the privy chamber and selected in 1702 to carry the canopy at the funeral of William III. An esteemed scholar of Latin poetry at Cambridge, he represented the university in the House of Commons for eight years, even defeating Sir Isaac Newton for the post in 1705. Arthur was the preeminent figure in an extended family of nearly two dozen households scattered across Ireland and England.23

Wedded in 1702 to his English cousin Mary, daughter of Sir John Thompson, Baron Haversham, Arthur was the family’s last hope to preserve a line of descent from his father James, great-grandson of the adventurer Robert Annesley. If, on the other hand, he and Mary failed to conceive a male heir, the family’s hereditary honors might still endure, including the Annesleys’ most esteemed title, the earldom of Anglesea; but rather than descending directly on the main stem of the genealogical tree, the line would instead fork sideways to an uncle or a cousin. Either path was problematic, depending upon the heir’s age, character, and upbringing. For an idle relation not trained from infancy to assume the family honors, the acquisition of a peerage could be both dizzying and dangerous. The risk was that the new lord might prove indifferent to customary constraints and put his own well-being above the long-term interests of the family. Still, for the time being at least, the catastrophic loss of one or more peerages would be averted.24

Arthur’s uncle, first Baron Altham, would have received precedence had he not expired in 1699, as did his infant son soon afterward. In their stead, occupying one of the tree’s few remaining branches, was yet another uncle, Richard Annesley, dean of Exeter cathedral. Although Richard died two years later in London at the age of forty-six, his wife, Dorothea, had given birth, years earlier, to not one boy but two, Arthur and Richard. If no son was born to the fifth earl, the fate of the mighty house of Annesley lay with them: the future father and uncle, respectively, of Jemmy Annesley.25

One might have expected more from this remote bough of the family tree. Richard Annesley the elder, after all, was no scoundrel. He had received an enviable education, attending, like his father Arthur, Magdalen College, Oxford, where in 1671 he took the degree of Master of Arts. Later, he returned to the university to earn his Doctor of Divinity degree, serving in the interim in a succession of church offices, including that of a prebendary (clergyman) at Westminster Abbey (his final resting place in 1701). Following in the path of his deceased brother, Richard inherited the baronetcy of Altham. Not that his life always stayed above the fray. After a fracas in a London tavern, he was chastised for swearing obscenely at another clergyman. Consequently, only because of his father’s intervention as lord privy seal did Richard in 1681 obtain his deanship.26

Arthur, his eldest son, was born eight years later. Little is known of his childhood in Exeter, other than the painful impact, at age twelve, that his father’s death must have had. Autobiographies from the period bear witness to the trauma of the loss of a parent, as do descriptions of funerals. “The cries of the children at the funeral moved most that were present,” noted a Lancashire clergyman at the burial of a widower in 1659.27

Worsening mortality rates meant that numerous sons became fatherless at a tender age, with all the attendant opportunities and responsibilities. Many young men stood to inherit their father’s property sooner in life. By the late 1600s, the median age of male heirs had plummeted from twenty-nine a century earlier to just nineteen. Barely an adolescent, Arthur became fourth Baron Altham, bereft of the strong guidance that his father might have provided. Nor would parental approval now be necessary in Arthur’s choice of a wife.28

Had consent been required, Altham might have been spared years of unhappiness. In April 1703, at just fourteen, he wed a cousin, Phillipa Thompson, another daughter of Lord Haversham, in St. Margaret’s Church, next to Westminster Abbey. Among the aristocracy, early marriages were promoted in order to secure a suitable partner. Arthur’s match enjoyed the family’s blessing, but after Phillipa’s death one year later, he wed again in July 1707, this time over the angry protests of his mother. His new wife was Mary Sheffield, tall in stature, with dark brown hair and an olive complexion. A pleasing young woman, she may have been an impulsive choice. Mary was the illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Buckingham, so more than love alone, quite possibly, played a role in the baron’s decision.29

In general, by the early 1700s, members of the English aristocracy, in the selection of mates, proved more open than earlier generations to affairs of the heart, though increasing one’s income or status still remained an important consideration. “Who marries for love without money has good nights and sorry days,” averred an English proverb. Aside from the bride’s “natural” birth, opposition from the Annesleys probably arose over Buckingham’s recent marriage to the widow of James Annesley, whose allegation of attempted murder before the House of Lords, just a few years earlier, still irked the family (as Buckingham’s third wife, the duchess was thirty-four years his junior). It did not help that the duke had already attracted the enmity of his fellow High Tory, Arthur, the future Earl of Anglesea. This was an era of intense political strife, within as well as between parties, and Arthur desperately tried to thwart his young cousin’s wedding.30

Whatever his own misgivings, Buckingham, a grand lion of court politics, not only consented to the union but also promised a generous dowry of £2,000 once his son-in-law turned twenty-one, the age of majority (the father of several illegitimate children, the duke faithfully supported them all). According to custom, the groom, in turn, pledged a jointure that would afford his wife an annuity of £400 in the event of his death. A more immediate source of income for the young lord consisted of property, leased by tenants, in two Leinster counties. Besides 1,800 acres in Meath, he possessed in Wexford a prominent portion of the town of New Ross, a prosperous inland port on the River Barrow some seventy miles southwest of Dublin. In 1701, only days after the death of Richard Annesley, Altham’s cousin James had bequeathed these properties to him, to the dismay of others in the family. Then, also, according to his father’s own will, Altham, on his twenty-first birthday, stood to receive additional lands in Ireland and England.31

But those estates, like his wife’s dowry, lay in the future. In the meantime, expenses at the couple’s London home rapidly mounted. A short, homely man of slight build with gray eyes and black eyebrows, the baron delighted in low pleasures. He was not one to stand on ceremony. A favorite haunt, to judge from an unpaid debt of nearly £20, was a Chelsea alehouse. Like other budding blades, he also seems to have enjoyed gambling, including the fashionable card game basset, first introduced in Venice during the fifteenth century. In 1706, a popular London comedy, The Basset-Table, was dedicated in his honor, though the playwright, Susanna Centilivre, declined to expound upon her patron’s “personal virtues,” a task, she wrote (perhaps ironically), “to which I freely own my ability is unequal.” 32

Larger financial obligations ensued, including, by the terms of the original marriage contract, £800 drawn against his wife’s dowry, now mostly squandered. Quarrels erupted at home, which the couple shared with Altham’s mother and sister. By the following year, he was heavily in debt. Adopting a frugal lifestyle appears to have been out of the question, as was the likelihood of entering a profession. By definition, a nobleman born to inherited privilege was a gentleman of leisure with neither the need nor the taste for the pursuit of worldly success. “It was the essence of a gentleman’s character,” wrote Samuel Johnson, “to bear the visible mark of no profession whatsoever.” In the end, the baron followed the one path open to an impoverished young rake. He deserted his wife and fled London.33

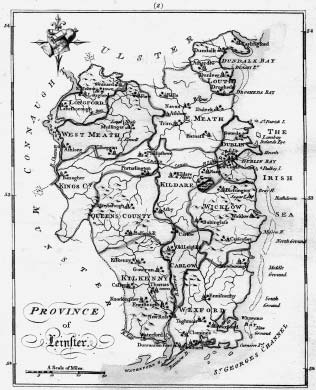

Bernard Scalé, Province of Leinster, 1776.

That Altham should take up residence in Ireland, in which he had not previously set foot, testified both to his poverty and to his troubled marriage. In recent decades, the wealthiest Annesleys had become absentee landlords. For the first Earl of Anglesea and many of his lineal descendants, court society in London exerted a powerful pull, as did membership in the House of Lords. And, too, many Annesley men married into aristocratic English families, as did a number of the women.34

With property in New Ross, Altham removed to County Wexford. Bounded by St. George’s Channel and the Irish Sea on the east and the Atlantic to the south, much of the countryside consisted of lowlands with scattered hills and ridges stretching north from the coast to the Blackstairs Mountains. Hedgerows and groves of trees helped to break the uniformity of the undulating landscape. In the south and east, the rich soil commanded some of the highest rents in Ireland, producing oats, wheat, and barley as well as providing grazing land for cattle and sheep. Contrary to popular thought, potatoes, while common, did not dominate the Irish diet. A seasonal foodstuff, unlike bread for instance, they were limited mostly to winter and spring.35

With the seaport of Wexford twenty miles to the east, New Ross lay on the county’s far western border, separated from the county of Kilkenny by the Barrow. Unusually deep, the river permitted large ships to dock beside a small quay. Major exports included wool, butter, and beef. The town sat on a sloping hillside, with steps descending to the water’s edge. Although called New Ross (in contrast to nearby Old Ross), crumbling battlements bore witness to the community’s medieval origins. When Oliver Cromwell laid siege in 1649, the inhabitants wisely surrendered after the Aldgate received three blasts of cannonfire (it now bears the name of the Three Bullet Gate). As for “society or amusement,” observed an eighteenth-century writer, New Ross was “no place for either.” 36

Just seven miles south of the town along a “very indifferent road” lay Dunmain, which Altham chose for a country home. The estate belonged to the Colcloughs, an ancient Catholic family with extensive property in the county. Containing nearly 400 acres of mostly arable land amid small knolls and bogs, Dunmain was let to a tenant, Aaron Lambert, for the yearly sum of £17, plus “a fat hog, a summer sheep, and a couple of fat hens.” Lambert, in turn, sublet the estate to the baron. Far from making a profit, however, he would lend Altham £500 in coming months, a testament to the clout of even a poor nobleman.37

George Holmes, New Ross, Co. Wexford, 1791. Long after the arrival of Baron Altham, New Ross remained a modest inland port.

The house, which still stands, was no turf cottage. Constructed in the late seventeenth century, the two-story gray structure boasted a formidable stone façade with a steeply pitched gable roof. Massive granite steps thrust forward from double doors in the center. Like sentries, twin turrets with conical roofs stood watch, one on either side of the main edifice, which contained a dining room, kitchen, parlors, and several bedchambers. Along with basement quarters for servants, the turrets themselves contained small rooms on each floor. In the rear of the house, a high wall enclosed the yard and stables, suggesting lingering fears of military conflict at the time of the manse’s construction.

Anonymous, Dunmain House, n.d. The exterior of Dunmain still appears much as it did three hundred years ago, except for the addition of the front portico.

Though a newcomer, the young lord quickly embraced the full-blooded life of a country squire. Although appointed a justice of the peace in 1712, he had little enthusiasm for the office’s duties, much less any interest in pursuing a higher post in Dublin other than attending the House of Lords. Unlike justices who faithfully frequented sessions to hear cases and tend to administrative matters, he regarded the office more as a sinecure than a stepping stone. Power was not Altham’s abiding passion, as it had been for others in the family. Nor, like some country magnates, did he feel a paternalistic need, through public service, to justify his privileged status. It is telling, as a sign of his isolation, that he barely knew Nicholas Loftus, scion of one of the most politically prominent families in the county, despite the proximity of Loftus Hall, just ten miles south of Dunmain on the Hook peninsula (not once did Altham or Loftus ever visit the other’s seat). Instead, the baron’s priorities were more mundane, best expressed perhaps upon offering a servant employment. “If you come to live with me,” he promised, “you shall never want a shilling in your pocket, a gun to fowl, a horse to ride, or a whore” (the offer was accepted). 38

Rural sports occupied Altham’s days, especially hunting, for which he kept a half-dozen horses and a kennel of prized hounds along with a huntsman and a dog-boy named Smutty. By law, as in England, blood sports remained the preserve of the landed elite. Favorite game included deer, fowl, and hares. He also relished the ancient sport of hurling. The variety known as báire or ioman was native to southern Ireland and played during the spring and summer. Players wielded wooden sticks (hurls) to strike or carry a soft ball of animal hair, a sliothar, to score goals at opposing ends of an immense green. It was a fast-paced, skillful, and, at times, violent contest requiring agility, speed, and strength. A Wexford critic claimed, “I’ve heard of several persons being killed on the spot, and others never recovering from the bruises.” Drawing large crowds, matches were fought between teams representing local magnates. Players for Caesar Colclough of Tintern Abbey wore yellow sashes, for which they were called “yellow bellies,” a term still used today for residents of County Wexford. Lord Altham, in addition to recruiting players, typically sponsored a match on St. George’s Day, celebrated every April in honor of England’s patron saint. Foot races and dancing accompanied the contest.39

Such “merriments” showcased the baron’s generosity. Clearly, he delighted in the unaffected camaraderie of country folk, Catholics and Protestants alike. A critic later remarked that “he was naturally inclined to low company.” “He was a very free man,” attested the keeper of a drinking house, close to the soil in both speech and manner. Often, after a day’s hunt, Altham would visit the home of a Catholic priest for a cup of whiskey punch. Alcohol lubricated most social gatherings, including occasional dinners at Dunmain where toasts were the order of the night. Guests might include farmers along with a handful of landed gentlemen. The lord bore a reputation for suffering no one to depart before dawn. Stragglers might linger for a breakfast of mulled wine in a nook nicknamed “Sot’s Hole.” 40

And Lady Altham? The baron’s wife remained marooned in London with modest assistance from her father, the duke. Lord Altham seems to have entertained the thought of divorce after receiving dubious tales from his mother of Mary’s infidelity. That, however, would have been difficult to obtain, for the Anglican church only sanctioned formal separations, which did not permit parties to remarry, even in instances of adultery or physical abuse, unless a spouse disappeared for a span of seven years and was presumed dead (should the spouse reappear, however, the original marriage resumed precedence). For a divorce, the sole expedient was a private act of Parliament, though these were rare and expensive. Between 1670 and 1750, only seventeen such acts were passed.41

By 1713, Altham was willing to attempt reconciliation, promoted at the time by Buckingham. Whatever the baron’s regard for Mary, he had reason to expect, having attained the age of majority, the remainder of her dowry. Still more critical, reconciliation held out the hope of a male heir, placing not only Altham but his son in line to inherit four additional titles, including the earldom of Anglesea. The incumbent, his older cousin Arthur, remained childless, even though he and his wife had been married for eleven years.42

Early December ushered in Dublin’s “dirty days”—cold, wet, and short. At Buckingham’s urging, Lord and Lady Altham agreed to meet, in the city, for the first time in five years. Just south of Christ Church, they reunited at the home of Captain Temple Brisco and his wife. Brisco was the duke’s man in Dublin; there, in Brides Alley, Mary had resided for the past six weeks. The reunion was a happy one, as the captain could report to Buckingham—the entire family having seen the couple to bed one evening. After several days, lord and lady took lodgings in Temple Bar, close to the Liffey, until, finally, on Christmas Eve, they returned by coach to Dunmain as bonfires lit the darkness and servants turned out in welcome.43

Within aristocratic circles, the institution of marriage underwent a gradual transition in the eighteenth century. With greater allowance for personal preference, no longer were adolescents invariably consigned to unhappy unions by hopes of preferment and financial advantage. Companionship became more common between couples, with wives performing a valued role in managing the household. The drawbacks of traditional matrimony, in turn, were vividly portrayed in the popular play The Beaux’ Stratagem by the Irishman George Farquhar, first performed in 1707, the year of the Annesleys’ wedding. Among the central characters were Squire Sullen and his wife, whose marriage portion of £10,000 only produced indifference and neglect from her sodden husband. In the end, they were formally separated, though not before the squire was forced to forfeit the handsome dowry.44

Of course, many “companionate marriages” also ended in failure, especially when embarked upon at a young age. Nor, in the case of Lord and Lady Altham, is it clear that mutual affection was the original basis of their marriage. And yet during the winter prospects for a successful union were encouraging. Rarely in the past had Altham been so attentive to his wife’s wishes. Though a proud woman, Mary seemed determined to make the best of life at Dunmain, joining her husband at hurling matches and entertaining local landowners over dinner. On Sundays, she frequented a nearby church at Kilmokea. Despite their isolation from London, she betrayed no evident sign of homesickness or regret. Besides her maidservant, Mary Heath, a slight woman with black hair, the baroness enjoyed a staff of more than a dozen servants, from the housekeeper Mrs. Settright to “little black Nell,” the so-called weeding wench known for her swarthy complexion.45

A hopeful start, but just that. There were limits to Altham’s gallantry, which did not come naturally. As more than one person noted, he was a highly-strung man with a sharp temper. In the spring, Mrs. Brisco and her daughter Henrietta visited from Dublin. Having befriended the young couple, the captain’s wife may have felt an obligation to stay informed, if only for the sake of Mary’s father.46 But at dinner one evening, the lord erupted in fury over the housekeeper’s choice of saucers on which to serve sweet-meats. The china, acquired years earlier by Altham, was decorated with a series of obscene images, and, following Mary’s arrival, he had issued orders never again to use it. Altham hurled the saucers into a fireplace, barely missing his wife at the opposite end of the table. One senses in his anger a glimmer of embarrassment for Mary, who, erupting into tears, retreated to the bedchamber. Worse, having only recently become pregnant, she miscarried later that night.47

This misfortune was not the last. In July, she again miscarried, this time following the baron’s return late one night from a drunken rout, when he threw a bed stool in the direction of her maidservant. “You have done a fine thing, my lady has miscarried,” Mary Heath later scolded him, adding that her mistress “would be as fruitful a woman as any in the kingdom,” were it not for his “ill-usage.” It was only that autumn, after his wife became pregnant for a third time, that Altham attempted to make amends by curbing his nights at a nearby alehouse. Among other small acts of kindness, he purchased for Mary a pair of low-heeled slippers to prevent an accidental fall and yet another miscarriage. A cane lent added support. Without doubt, the baron was anxious for a son, or, as he liked to predict, “an Irish bull.” “By God,” he exclaimed, clapping a servant on the back in November, “Moll’s with child!” 48

Spring brought the birth of a baby boy, just days after the spectacular solar eclipse in late April of 1715. If any in the house thought it an ill omen, like other celestial marvels, no one seems to have said so. Brought to bed at dusk in the upstairs chamber called the Yellow Room, Mary, who felt ill, was first bled by a surgeon, in keeping with common medical procedure, to relieve a harmful build-up of blood, the supposed source of myriad maladies. Once the vein was lanced, a narrow stream of blood trickled from her arm onto a pewter plate. Later, kneeling on a sheet, she endured a relatively brief labor of three hours with the aid of a seasoned midwife, Mrs. Shiels, from New Ross. Bathed in a mixture of water and brandy, the infant was given the name of James in honor of Altham’s late cousin and benefactor. “That is a strong boy,” remarked an attendant, “hear how strongly he cries.” 49

The following night, dinner guests celebrated the heir apparent to the Earl of Anglesea with wine and whiskey. Milk pails brimming with ale were carried outside. To the joyful sound of fiddles and uileann pipes, laborers and servants drank, danced, and frolicked by a large bonfire in a clearing beyond the house. Five cart-loads of furze and timber fueled the blaze. They drank, recalled the servant Patrick Closey, “to the safe uprising of…Lady Altham and long life to her new born son.” The baron was seen to toss his hat in the air. Strangely—probably he was drunk—he ordered that all bottles and glasses be broken, an act that in Gaelic tradition portended ill fortune. Before the night was out, more than a few revelers lay intoxicated in ditches, one of whom was found dead the next morning.50

Three weeks later, the parish minister christened the baby in the large parlor at Dunmain amid plum cake and wine. From landowners and substantial tenants, there were gifts of money, and from others, eggs and live chickens, symbols of childbirth and motherhood. In attendance were three “gossips,” the traditional term for godparents. Selected for their friendship and loyalty were the county squire Anthony Colclough, Anthony Cliff, a New Ross lawyer, and Mary’s confidante, Mrs. Piggot. At dinner, healths were drunk, a British custom popular after the Restoration, whereby mother and son—the “lady in the straw” and the “young Christian”—were each toasted. Outdoors, servants and laborers drank from piggins and pails of punch.51

Among the island’s ranking families, it was common to enlist a wet-nurse for a newborn’s care. As in England, aristocratic women found breastfeeding inconvenient and degrading. Some feared that it aged one’s appearance. Equally important, as contemporaries recognized, lactation ordinarily delays the onset of ovulation. Despite the risk to their health, wives were repeatedly encouraged to augment the family’s male line, with often just eighteen months separating one birth from the next. As one historian has written, “Rich women [were] tied to perpetual pregnancy and poor mothers to perpetual suckling”—sometimes resulting in insufficient nourishment for their own infants.52

Finding an experienced wet-nurse of good character was a time-consuming task. With the help of a doctor, Lady Altham interviewed several candidates from the neighborhood, including one in poor health and another whose milk tasted bitter. Proximity to the great house was essential. One nurse declined interest on learning of the lord’s “very bad character”—for which “she would gain no credit being in his service”—only to be upbraided later for her foolish judgment. “It would have been worth a hundred pounds a year to her,” insisted a friend. “Though Lord Altham’s fortune was but small, yet if his son lived till after the death of Arthur…Lord Anglesea, he would have a very large one.” 53

The choice fell on a young kitchen-maid on the estate named Joan, or “Juggy,” Landy, known for bearing some of the “best milk” in the parish of Tintern. A single mother, Landy and her son lived with her parents just two fields from Dunmain, a short distance beyond the dog kennels. There, in a small thatched cottage—partitioned for privacy and freshly whitewashed for cleanliness—she cared for the infant for a year, nursing, bathing, and dressing him “in the English way,” according to Lady Altham’s instructions (probably in keeping with the growing prejudice against swaddling in order to permit babies greater freedom of movement). A stone chimney was constructed for added warmth, and a plain looking glass hung on a wall. Servants also laid a new coach road, made of gravel with drains on either side, which ran from the cottage across a bog, called the Currah, to permit easy visits back and forth, including deliveries of jellies to sweeten Landy’s whey (the liquid residue, rich in protein, from curdled milk). Not permitted were greens, potatoes, or roots. Afternoons often found Lady Altham having tea at the cabin. On returning to Dunmain for good, Jemmy, with leading straps fastened to his clothing and his mother’s help, learned to walk on the bowling green out front. He also joined her on occasional jaunts to New Ross. Playmates at home included the children of servants, one of whom—the son of a coachman—recollected years later how “very fond” Mary was of her young son.54