Barely fifty feet from the Dublin crypt containing the corrupted remains of James Annesley’s father, Lord Altham, stood a nondescript stone building known as the Four Courts. Ever since 1608, the central law courts of Ireland had been housed in the former two-story home of the dean of Christ Church. Located beside the cathedral, the building had last been renovated at the end of the seventeenth century. Simplicity itself, the main floor of the edifice was neither elegant nor functional. A French visitor pronounced the building and its denizens equally gloomy. The compact courtrooms faced a common hallway without doors or curtains. There was minimal ornamentation—arched doorways and windows, pilastered frames, and a dome in the center of the ceiling. On one side were the courts of Exchequer and Chancery; directly across the vestibule lay King’s Bench and Common Pleas—all “fill’d in term-time,” quipped Swift, “with those who defend their own estate or endeavour to get another’s.” The clamor must have been overwhelming. Adding to the noise, both the cellar and the upper floor of the building were leased to spinners and shopkeepers, a source of “great annoyance” to the lawyers and judges sandwiched in between.2

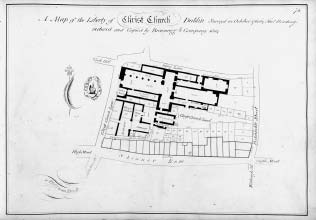

Thomas Reading, Map of the Liberty of Christ Church Dublin Survey’d in October 1761…, 1761. The drawing offers a detailed layout of the Four Courts as well as of Christ Church. The alley known as “Hell” appears as the “Passage from Christ Church Lane.”

An alleyway ran from Christ Church Lane (on the western edge of the cathedral) to the Courts’ rear. As dark as it was narrow, the passage, like a trench, lay partly below ground. Along the path, a door opened onto the central hall inside, just to the left of the Court of Exchequer. Owing either to the passage’s appearance or to its terminus, it was famously dubbed “Hell.” An advertisement for nearby lodgings announced the availability of “furnished apartments in Hell.” “They are well suited to a lawyer,” the ad declared.3

Crumbling plaster, decaying joists, and loose floorboards were among the problems besetting the Four Courts. In 1739, the courtroom belonging to Exchequer was found to be in “ruinous” condition. Beams had to be placed as “props” to forestall the ceiling’s collapse. Equally problematic were the building’s cramped quarters. On a June afternoon in 1721, the sight of billowing smoke from a clogged chimney sent persons from all four courtrooms spilling into the hallway, where one of the few doors was locked to prevent the escape of prisoners. More than one hundred men and women were injured, with between twenty and thirty either suffocated by the smoke or trampled to death in the crowd’s frenzy.4

The first week of November was windy and wet, followed by frosty temperatures and gusts from the north and northwest. A spell of “dark mizzling weather” then set in for most of the month—cold and drizzly. All the same, neither the weather nor, for that matter, the Courts’ physical deterioration could detract attention from the singular case Exchequer was set to hear. Since his arrival from the Caribbean, the saga of James Annesley had become a sensation throughout the British Isles—“the common conversation of the coffee-houses,” observed a London resident. Now, with another dramatic trial looming, public interest had only intensified. As early as January, Dr. Barry had written to the Earl of Orrery, “We all expect the trial with impatience.” Recent events at the Curragh, awaiting a separate hearing, fed the anticipation. “We hear from Ireland,” the Westminster Journal reported, “that the life of the Hon. James Annesley, Esq. has been twice attempted there.” 5

Certainly, there were no illusions about the contest’s significance. Ostensibly a dispute over competing leases, the case’s larger import—as the first step toward Annesley’s vindication—was apparent to all. Never, potentially, did any jury have five peerages and such an immense estate at its disposal, now worth by one account at least £50,000 a year. No less momentous in the public mind were the lurid allegations of aristocratic wrongdoing, which, for James’s following, had robbed a peer of the realm of his birthright and broken the chain of succession within the house of Annesley.

Richard’s circle, by contrast, bewailed the prospect of elevating a false claimant to the family’s hereditary honors, not unlike Jacobite efforts to place a Stuart heir on the throne. Opponents commonly derided James as a “pretender,” the slur attached to successive generations of Jacobite claimants. With the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession and renewed Protestant fears in 1743 of a Franco-Jacobite invasion of Ireland, the label “pretender” had widespread resonance.6

Plainly no previous peerage controversy, except for struggles over the throne itself, so captivated the popular imagination. The current contest, wrote Viscount Perceval to his father, the Earl of Egmont, was “perhaps of greater importance than any tryall ever known in this or any other kingdom.” 7

The court convened at eight o’clock on the morning of Friday, November 11, despite an attempt by Anglesea’s lawyers to obtain an injunction halting the trial. The first day occasioned, in the words of one correspondent, “the greatest concourse of people, hurry, and confusion in a court of justice that has been known in the memory of man.” Nearly everything about the proceedings suggested their enormity. Fearing violence, the lord lieutenant, William Cavendish, third Duke of Devonshire, stationed a military guard just across the street at the Tholsel. Parliament met sporadically at best for the duration of the trial, with many of its members among the throng that each day packed the courtroom.8

At least two of the three judges, attired in silk robes trimmed with miniver, were figures of weight and reputation. The chief baron of the Court of Exchequer was John Bowes, who besides serving as solicitor-general and then attorney-general had represented the borough of Taghmon in County Wexford in the Irish House of Commons, where he had been a staunch advocate for English interests. As a lawyer, he was praised for “the music of his voice, and the gracefulness of his elocution.” 9

Anonymous, John Bowes, Chief Baron of the Exchequer, mezzotint by John Brooks, ca. 1741.

The second baron, Richard Mountney, was a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, and a classical scholar before being called to the bar in 1732. Arthur Dawson, the court’s third baron and only native of Ireland, had served as member of Parliament for County Londonderry from 1729 to 1742. He was less well known for his legal expertise than for his authorship of a bacchanalian ditty that proclaimed, “Ye lawyers so just, / Be the cause what it will, who so learnedly plead, / How worthy of trust! / You know black from white, / Yet prefer wrong to right.” 10

Each side in the contest employed an imposing legion of lawyers. As barristers, all came from the upper ranks of the country’s legal establishment, in contrast to attorneys and solicitors, who were not allowed to plead in higher courts. Opponents of the earl later alleged that he had monopolized the city’s most eminent barristers; and, in fact, his fifteen counselors included the top four lawyers in the kingdom, not only the attorney-general and his deputy, the solicitor-general, but also the prime serjeant and the recorder of Dublin, all of whom had the right to accept private clients so long as the king was not a party. To represent Campbell Craig and Annesley, as the “lessor of the plaintiff,” Mackercher retained the second and third serjeants to lead a panel of thirteen lawyers. With some two hundred barristers in Dublin, nearly one in seven participated on one side or the other during the trial.11

Equally remarkable were the jurors brought from County Meath, site of the disputed estate. From a pool of twenty-four men of independent wealth, as required by law, twelve were selected, their names written on tickets picked out of a box. Included were many of the county’s biggest landowners, possessing estates collectively worth more than £70,000 per annum. Although several jurors reportedly stood to lose lucrative leases to pieces of the disputed property should Craig and Annesley prevail, they were not disqualified. Fully ten were members of the House of Commons. “Nor ever was there a jury composed of gentlemen of such property, dignity, and character,” reported a letter from Dublin.12

Once the jurors had been sworn in, Craig’s formal complaint, describing his ejectment “with force and arms,” was read in court. The events of May 3 were not contested by Anglesea’s lawyers. Instead, two other issues came to dominate the proceedings. Most important was whether James Annesley was the son and rightful heir of Arthur, Baron Altham; and second, whether, after a prolonged absence abroad, the lessor of land to Campbell Craig was in fact Annesley and not an impostor.13

Serjeant Robert Marshall gave the opening remarks for the plaintiff. Forty-six years old, he was a native of County Tipperary, which he had aggressively represented in Parliament since 1727. A practicing lawyer for twenty years, he spent close to an hour tracing the chronology of the case, beginning with the union of Annesley’s parents and concluding with his recent trial at the Old Bailey. As for his kidnapping, Marshall was deliberately coy, promising to reveal the villain’s identity in the course of the trial. “It will much more properly come out of the mouths of the witnesses,” he stated. Not scheduled to testify was Annesley himself—nor, for that matter, his uncle, the earl. In contrast to accepted practice in criminal trials, interested parties in civil proceedings would not be permitted to give testimony until the mid-nineteenth century.14

Over the remainder of the day and into the night, fourteen witnesses took an oath not to forswear themselves. Following the clerk’s admonition to “tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth,” each was required to kiss the Bible. Consisting, in the main, of former servants, neighbors, and family friends, most gave detailed descriptions of Lady Altham’s pregnancy and Jemmy’s birth. With the courtroom aglow in candlelight, two women, Mary Doyle and Ellen Murphy, claimed to have been in the room during the delivery. The absence of a parish register made such testimony critical. Memorable events, such as the festive celebrations following Jemmy’s birth and christening, stood out in the statements. The most compelling witness was Major Richard Fitzgerald of Prospect Hall in Waterford, on leave from serving in the Queen of Hungary’s troops in the Rhineland. On the day after the boy’s birth, he had visited Dunmain. Having been pressed to stay for dinner, he recalled kissing the baby and giving his nurse a half-guinea. Lord Altham, he testified, was “in high spirits with the thoughts of having a son and heir.” In contrast, however, to other witnesses, Fitzgerald recalled that the birth had occurred not in the spring but in the fall.15

In the late evening, the jurors also heard from the widow, Deborah Annesley, who twenty-five years earlier had refused to board Baron Altham at her Kildare estate. At sixty years of age, she was the aunt of Francis Annesley of Ballysax as well as Anglesea’s cousin. More important, she remained a figure of strict propriety and in the weeks approaching the trial had rejected her nephew’s urgent pleas not to testify as doing so, he claimed, would cause the family’s ruin.

Called to the bar, Deborah stood her ground. Volunteering that she had never seen the baron’s boy—preferring, as she did, not to visit Kinnea—she nonetheless insisted that he was always thought to be Altham’s heir. Members of her household were known to drink Jemmy’s health. Her late brother, Deborah Annesley testified, “was a sober, grave man” who “would not have toasted the health of the child if he had been a bastard.” What’s more, on Altham’s death in 1727, they had “enquired what was become of that boy, but never could learn.”

Not until 11 p.m. did the court finally adjourn. Rarely, particularly in the short days of fall and winter, did courts sit so late. It was only the second time in memory that such a trial had extended beyond a single day, and there was no end in sight.16

All day Saturday and well into the next week, Sunday excepted, the court heard from a steady stream of witnesses for the plaintiff. Any notion that this would be a routine trial had long been abandoned. Sessions continued to run late, convening at 8 or 9 a.m. and not adjourning until long past dark, with only brief intervals for “refreshment.”

Among those to appear on Saturday was Joan Laffan, Jemmy’s former dry-nurse. In recounting the fracas preceding the baroness’s expulsion from Dunmain, she told of the cut inflicted upon Tom Palliser’s ear. Immediately afterward, she related, Jemmy had pointed to drops of blood on the floor. On cross-examination, Anglesea’s counsel questioned whether she had ever resided at Dunmain. Besides challenging her knowledge of other servants, he expressed surprise at her ignorance of one of Altham’s neighbors.

“Did not you know that he was reckoned a gentleman of estate and a justice of the peace?” demanded the defense.

“Well,” replied Laffan, without hesitation, “there are a great many indifferent men [who are] justices of the peace in our country.” 17

In this instance and others, cross-examinations, initially perfunctory in tone, grew sharper. Nor did opposing counsel shrink from impugning a witness’s social credentials. James Dempsey testified to his employment at Carrickduff as tutor to Jemmy for six months in 1721. Recently, he had been reintroduced to his former student, whom he had immediately recognized.

“Do you go to mass or to church,” asked the defense lawyer during cross-examination, playing upon anti-Catholic animus among the jury.

“I go to mass, but I did not know much of religion when I tutored Mr. Annesley, for during the six months that I staid in the house I neither went to church or mass, but I have a better notion of religion now,” he said, adding, “thank God.” 18

By contrast, Nicholas Duff, a tavernkeeper who had known Altham and his son during their residence on Cross-Lane, was ridiculed for his genteel pretensions. “Have you ever carried a chair?” questioned the defense.

“What of that? I am a gentleman now.”

“Are you a porter to Mr. Mackercher?”

“No, I don’t go of errands.”

“Do you open Mr. Mackercher’s door to people?”

“Sometime, I open it,” Duff confessed, “but I have no wages. I tend to oblige Mr. Annesley and Mr. Mackercher.”

If that was not humiliation enough, the counsel asked if he had ever swept the walk before Mackercher’s door.

“No!” came the angry reply.

“How long have you had the coat now on your back?” goaded the defense.

“Ever since I bought it last spring. Why don’t you ask me where I bought this wig?”

Finally, questioned at whose direction he stood at Mackercher’s door, Duff responded, “By my own directions, to divert me, for my own pleasure, for unless I did it I should go into an ale-house to drink.”

Of the exchange, a witness in the gallery reported that Duff’s posturing “made the court very merry.” 19

Moments of levity, however mean-spirited, were few. Lighter in tone was the testimony of Bartholomew Furlong, whose wife, he stated, had been interviewed years earlier by Lady Altham as a potential wet-nurse. Determined to cast doubt upon his testimony, the defense counsel pressed for accurate descriptions of Altham and his wife. The baron, Furlong replied, was a “very small faced, thin, little man, and spoke very loud.” Asked whether his wife was a “lean or a fat woman,” he replied, “She was not a fat woman.”

Pointing to a man in the audience, the counsel then inquired whether she was “as fair as that gentleman?”

“She was not so fair,” answered Furlong.

“Of what complexion is your wife?”

“She is a brown woman. Lady Altham was not of the same colour, [and] that they ought not (in one day) to be compared together,” adding, “to be sure, Lady Altham was fifty times beyond my wife, though my wife is more pleasing to me.” 20

By Monday afternoon, the court had heard thirty-nine witnesses for the plaintiff, evoking vivid memories of Jemmy Annesley at varying stages of his youth. Now, the focus of the testimony shifted abruptly to the period preceding his kidnapping. Still a butcher, brawny John Purcell approached the bar. What followed was a riveting tale of the months Jemmy had spent with Purcell and his family on Phoenix Street—and of the earl’s attempt to abduct the boy while under the butcher’s care.

Asked by the plaintiff’s lawyer whether he could identify James in court, Purcell pointed to Annesley and replied, “That is the gentleman there. I know him as well as I know the hand now on my heart.” During the cross-examination, the counsel directly challenged Purcell’s veracity. Why, he wondered, had the butcher not reported the attempted kidnapping in Ormond Market to the authorities? “If a man had come to take away your own child by force, would not you have gone to a justice of the peace to have given examinations against him?”

“I believe not,” replied Purcell, “for I thought myself capable of vindicating that cause” (i.e., redeem or rescue, according to the biblical meaning). Left unsaid was the deep distrust that tradesmen, especially Catholics like Purcell, felt toward constables and magistrates. In a letter to Lord Orrery, a friend reported that the four-hour testimony of the “brave, bold butcher” had caused most persons in the courtroom to weep.21

Still more unsettling was the account given early Tuesday morning by two men, Mark Byrn and James Reilly, who had participated in Jemmy’s abduction. With remarkable candor, they related not only their role in the day’s events but also Anglesea’s—the first evidence to link the earl directly to the kidnapping. Nothing was held back, not the boy’s wrenching capture nor his plaintive cries for help. Reilly, a former servant, testified to Richard’s frustration soon after his brother’s death. “I have heard the present Lord Anglesea very often say, when people used to affront him for destroying the boy’s birthright, that he would…[get] even with him.” Subsequent testimony by a customs officer as well as that of a former clerk to the merchant James Stephenson left no doubt that Annesley had departed Dublin aboard the James on April 30, 1728.22

It was not until the afternoon that the court called John Giffard, one of the final witnesses for the plaintiff. Anglesea could not have contemplated without alarm the testimony of his former attorney. For twenty years, Giffard had represented the earl, in and out of court, most recently as the manager of James Annesley’s prosecution for murder.

Costs stemming from the prosecution had totaled £800, well short of the £10,000 pledged by the earl during his initial euphoria. But, livid over his nephew’s acquittal, he had doggedly refused to pay Giffard a final sum of £330, filing instead a suit at the Court of Exchequer in London contesting Giffard’s claim, daring him to “set forth particularly all the business that he hath done.” It was a colossal blunder. Not only did Giffard respond by documenting his grievance with a detailed schedule of costs, listing names, places, and dates, but he also answered a series of interrogatories put by the court—all of which Daniel Mackercher, ever on the alert, caught wind of. Although Anglesea’s involvement in the prosecution had been alleged at the Old Bailey, few people at the time realized the extent of his participation. Stunned by Giffard’s incriminating evidence, Mackercher presented the solicitor with two choices: either come to Dublin to testify or face being subpoenaed—or such, at least, was Giffard’s subsequent explanation for his startling appearance Tuesday afternoon.23

Certainly he gave no sign of being a reluctant witness. Barely seconds into his testimony, John Fitzgibbon (nicknamed Wily John) enquired about the shooting at Staines. The defense objected, and Fitzgibbon countered by telling the court that Anglesea had funded the prosecution of his nephew, despite the possibility of his innocence—an allegation, responded the defense, wholly irrelevant to the case at hand. At that juncture Serjeant Marshall rose to speak. Anglesea’s role, he declared, revealed a deliberate design to prevent his nephew “from any possibility of asserting his birthright.” “What we now propose to lay before your lordship and the jury,” he emphasized, “is the very extraordinary part that the Earl of Anglesea took in that trial.” 24

Taken aback, the barons promised to give their opinions in the morning on whether or not to admit Giffard’s testimony about the Staines shooting. “The immense consequence” of “the present cause,” noted Baron Mountney, “will incline me to hesitate upon such points, as I should otherwise be most extremely clear in.” Reported a Dublin newspaper the next day, “The great tryal between the Right Hon. the Earl of Anglesea and James Annesley, Esq. which begun last Friday in his Majesty’s Court of Exchequer, still continues; and we hear, they have not yet examined all the witnesses for the plaintiff.” 25

When court convened at ten o’clock, William Harward for the plaintiff immediately revived the controversy over the admissibility of Giffard’s testimony, provoking, once again, the defense’s opposition. Before ruling, the court appeared anxious to hear further arguments. The defense counsel Francis Blake put forth a new line of reasoning by claiming attorney–client privilege: “An attorney or solicitor might not, nor is he compellable to disclose the secrets of his client.” It is a privilege, he argued, “not merely and solely” inherent in the office of the counsel “but is, in law and reason, the right and privilege of the client.” 26

In fact, the concept of attorney–client privilege was neither broadly defined nor deeply ingrained in the common law by the eighteenth century. First invoked in Elizabethan courts, the privilege only gained wider recognition during the second half of the seventeenth century. Even then, judges did not routinely uphold the principle, nor was it ordinarily thought applicable to solicitors and attorneys, like Giffard.27

If both sides in the trial acknowledged the principle’s legitimacy, both also accepted the need for restrictions. Beyond that, there was little consensus, particularly in relation to permitting Giffard’s testimony. Counselors spent the rest of the morning in vigorous debate, introducing early precedents but also expanding the boundaries of current law in new directions.

For the plaintiff, privilege in the present instance was objectionable for three reasons. First, Anglesea’s conversations with Giffard bore only an indirect connection to the pending litigation, occurring, as they had, well before the filing of Campbell Craig’s suit. Second, the bulk of their discourse regarding the earl’s nephew had occurred under the guise of friendship. No cause, not even Annesley’s prosecution, was then underway. Finally, privilege, counsel argued, could not be invoked to shield illegal behavior, malum in se, on the part of an attorney and his client, including the planning of a malicious prosecution. “Surely there never was a stronger instance of iniquity,” admonished Harward, “than the present; a design of the blackest dye against the life of an innocent person.”

Defense lawyers hotly disputed the validity of such burdensome criteria. Instead of rebutting specific arguments, they argued for a broader application of privilege. After all, declared John Smith, the earl’s status as Giffard’s client had commenced from the time of his initial retention until that of his dismissal. “Whatever my lord said to him during that space of time, touching his affairs, was plainly said to him under confidence as his attorney.” 28

By mid-afternoon, the court was ready to render its verdict. In a landmark decision that would influence rulings on the issue for another half-century, the barons unanimously found in favor of the plaintiff, all but gutting the principle of privilege. Giffard would be allowed to testify. For the chief baron, no comprehensive rule as to privilege existed. Each case needed to be examined on its own merits. In the matter at hand, the principle only protected discussions relating to pending litigation and even then could not be employed to conceal a criminal act. “As this was in part a wicked secret,” he stated, “it ought not to have been concealed; though, if earlier disclosed, it might have been more for the credit of the witness.” On these points his colleagues strongly concurred, with Lord Mountney taking the opportunity to chastise the defense for misconstruing existing case law on the subject.29

Giffard’s testimony lived up to its billing: direct and devastating. Richard quit the courtroom just as his former attorney approached the bar. Testifying to Anglesea’s legal battles with other members of the family, Giffard related the earl’s decision to abandon his titles and estates in favor of removing to France. Worse, Anglesea had conceded his nephew’s right to both.

“And, pray,” asked the plaintiff’s counsel, “what altered his resolution then?”

“Why, on the 1st of May, Mr. Annesley had shot a man at Staines.” And thus began the sordid story whereby Richard had ordered Giffard to initiate a prosecution, irrespective of either the cost or Annesley’s guilt or innocence.

The cross-examination of Giffard was combative. Turning to his role in the prosecution, the defense only succeeded in fixing blame for countenancing Anglesea’s malfeasance.

“When my lord Anglesea said that he would not care if it cost him £10,000 so he could get the plaintiff hanged,” inquired counsel, “did you apprehend from thence, that he would be willing to go to that expense in the prosecution?”

“I did.”

“Did you suppose from thence that he would dispose of that £10,000 in any shape to bring about the death of the plaintiff?”

“I did.”

“Did you not apprehend that to be a most wicked crime?”

“I did.”

“If so, how could you, who set yourself out as a man of business, engage in that project, without making any objection to it?”

“I may as well ask you, how you came to be engaged for the defendant in this suit,” Giffard sharply retorted.

Moments later, counsel returned to the subject of Giffard’s culpability.

“Did not you apprehend it to be a bad purpose to lay out money to compass the death of another man?”

“I do not know but I did. I do believe it, Sir. But I was not to undertake that bad purpose. If there was any dirty work, I was not concerned in it.”

“If you did believe this, I ask you, how came you to engage in this prosecution without objection?”

“I make a distinction,” he parried, “between carrying on a prosecution, and compassing the death of a man.”

In short, not unlike Anglesea’s current counselors, Giffard, in his role as attorney, was merely following his client’s wishes, not conspiring to abet a crime—an argument at odds with that made by plaintiff’s counsel for waiving attorney–client privilege.

No matter. Linking Giffard to Anglesea’s misconduct did nothing to diminish the force of his earlier testimony. Nor did defense suggestions that he would profit by a finding for the plaintiff. “I desire to know,” demanded the defense, “if Mr. Annesley gets this suit, whether you will be paid your bill of costs [owed by the earl]?” “No, Sir,” Giffard replied, “I shall lose every shilling of it.” Asked why he had agreed to testify about a former client, he replied, “This bill of costs of mine [for managing Annesley’s prosecution] would never have come to light, had I not been obligated to sue for my right.” 30

Late Wednesday afternoon, St. George Caulfeild, the attorney-general of Ireland, rose in a black silk gown to deliver opening remarks for the defense. The son of an Irish judge, he had been educated at the Middle Temple and later served in the Irish Commons. No portion of the plaintiff’s case went unscathed. At the center of Caulfeild’s attack was the issue of Annesley’s birth, which he attributed to an adulterous relationship between Lord Altham and the kitchen-maid Juggy Landy, the servant whom opposing counsel had already identified as Jemmy’s wet-nurse. Landy, Caulfeild pointedly noted, had not been summoned as a witness for the plaintiff (in truth, the defense had no plans to call her either, having had only limited success trying to suborn her testimony). But hadn’t the boy been kidnapped and shipped to America? Nonsense, Caulfeild insisted. He had traveled abroad voluntarily “without the least interposition on the part of the earl.” Maliciously prosecuted for homicide? A web of deceit spun by a disreputable witness. By contrast, the counselor promised to produce testimony over the coming days from “persons of the best conditions in the neighbourhood of Dunmain.” 31

After nearly two hours, the first witnesses were called, including Colonel Thomas Palliser, Sr. A former sheriff, he evidently harbored no ill feelings, at least toward Anglesea, for Lord Altham’s thrashing, years earlier, of his son Tom. Just the opposite. The baron’s only offspring, Palliser testified, was Landy’s bastard. What’s more, not long after the birth, she had been dismissed from Dunmain for “whoring”—an “infamous woman” whom the colonel “would not trust for the value of a potato.” Cross-examined for three hours, Palliser proved vague in many of his recollections, a consequence, intimated the defense, of his advanced age. During the testimony, he was permitted to deliver his remarks from a chair before the court finally adjourned at ten o’clock in the evening.32

Much of Thursday’s evidence continued to revolve around Juggy Landy’s illegitimate son. That she had borne a boy, counsel for the plaintiff had never disputed. But a sailor, they’d insisted, had fathered the child. Moreover, the infant was slightly older than James, and he had died at three years of age from smallpox. In fact, contended the defense, Juggy’s bastard—Jemmy Annesley—had been born in the Landys’ ramshackle cottage. Only after Lady Altham’s departure was the boy given a home at Dunmain and his father’s name. According to William Elmes, a neighbor, the baron forbade any intercourse between Landy and her son lest “the child should know his mother.” Once, on discovering her near the great house, Altham had threatened to set his hounds on her.

So different was this from the testimony of Joan Laffan that the court ordered her to return. Resworn after curtsying to the bench, she recalled only briefly encountering Elmes at Dunmain, though she judged him an honest man. For his part, Elmes, a former high constable, testified that Laffan had previously been charged with theft. He also described her as a laundry-maid, which she strongly denied, having been the boy’s dry-nurse. As for Jemmy, he was attired, she testified, as a nobleman’s son, usually in a silk or velvet coat, which Elmes claimed never to have observed.

He also disputed the condition of the Landys’ dwelling. “I saw no furniture at all. There was a wall made up with sods and stones.”

“Oh fie! Mr. Elmes,” exclaimed Laffan, clapping her hands. “I wonder you’ll say so. By the Holy Evangelists there was never a sod in the house!”

As with most of the defense’s witnesses, Elmes was questioned by counsel for the plaintiff by right of voir dire (“to see to speak”). This entitled counsel to probe whether the witness had an interest in the trial’s outcome. In Elmes’s case, he denied leasing land from Anglesea. Others responded along similar lines, disputing, as well, any expectation of compensation for their testimony. “I am no way concern’d to the value of a farthing,” responded one indignant witness.33

With evening coming on, Anne Giffard, the next person called, introduced a fresh line of defense. Lady Altham could not have given birth in the spring of 1715, for she, Giffard, and other ladies had traveled to the town of Wexford for a week to attend the assize trial of two men indicted for Jacobitism. Giffard even recollected that they had sat next to the young squire Caesar Colclough.

At eight o’clock, the court adjourned, though not before the chief baron forcefully urged opposing counsel to expedite their examination of witnesses. The case, he noted, was “of so extraordinary a nature that the business of the whole nation was postponed on account of it.” So ended the first week of a contest that was barely half over. “If Mr. A[nnesle]y carries it,” reported an observer, “it will be with the good will of all people here.” Nevertheless, he added, “What will be the event of it is impossible to determine.” 34

Over the next three days of testimony, a total of twenty-eight defense witnesses paraded before the court, most called to dispute either the birth of a son to Lord and Lady Altham or the quality of James’s upbringing. As a group, the witnesses were every bit as diverse as the plaintiff’s supporters, including not only a Dublin alderman but also servants and tradesmen, most of whom resided in County Wexford. Again and again, they affirmed the absence of a legitimate heir. Unlike Landy’s bastard, no such child had ever been seen or spoken of. Notably absent from the witness pool were any members of the Annesley family, including the earl’s cousins Charles and Francis, who may have chafed at the prospect of perjuring themselves.

The defense waited until Friday to call its prime witness. For thirteen years, Mary Heath had been the personal servant to Lady Altham, from the time of her arrival in Ireland until her death. Heath’s portrait of the Althams’ marriage, which consumed most of the afternoon, suggested little affection, much less love.

“Was there ever a child,” queried defense counsel, “either christened or living at that home while you were at Dunmain?”

“No, never.”

“Did my lady ever talk to you any thing of her being with child, or having had a child during that time?”

“No, never a word.”

Nearly as protracted was Heath’s cross-examination, though it was of little value to the plaintiff. A formidable witness, she had, by the end of the day, proved equal to the task, confirming not only the absence of an heir but also, for good measure, Lady Altham’s trip to Wexford in the spring of 1715.35

With the defense resting on Monday, plaintiff’s counsel exercised their right to call rebuttal witnesses. Right from the start, they attacked Heath’s testimony. According to Caesar Colclough, neither the baroness nor Mrs. Giffard had attended the Wexford assizes. If they had, he would have remembered them. “In a country town of that sort, if a lady of distinction comes, everybody hears it.” In his view, it was rare for women of privilege to attend such trials. As for the veracity of Mrs. Giffard, Colclough observed, “The family is reduced and very poor; their circumstances are altered, and so may their honesty.” 36

Worse, a London acquaintance of Heath, John Hussey, was also called to challenge her testimony. A reluctant witness, he had been subpoenaed late one night at his home in County Kildare. (As soon as the messenger pretended to bring news from Hussey’s sister, he had grudgingly opened his outer gate.) To the court, he testified to a conversation that he had with Heath over tea at her Holborn home in late 1741. Of Annesley’s arrival from the Caribbean, she had remarked, “Nobody knows that young man’s affairs better than I, because I long lived with his mother, the lady Altham.” In fact, Heath had “expressed a great deal of concern for him.” And, too, that during their final meeting in London, she had reported plans to travel to Ireland to testify, inexplicably, on behalf of the Earl of Anglesea.

The cross-examination was withering, but Hussey was adamant. A prolonged inquiry ensued into the nature of his trade, in which he denied ever having been a tailor but professed instead to deal in fabrics. He had also served as a steward aboard one of the royal yachts, Hussey proudly volunteered, thereby handing the defense an unexpected opening.

“You mentioned, that you had an employment under the Crown,” countered the counselor. “Pray, what is your profession in point of religion?”

“My Lord, I desire to know if that is material,” Hussey protested, “and I appeal to the court whether I must answer the question or not.”

“It is criminal,” interjected Serjeant Marshall for the plaintiff, “if a man accepts of an office under the Crown, and is not a Protestant,” adding, however, that Hussey was not required to incriminate himself. After further debate over the nature of his royal commission, Hussey at last attested to being a Catholic.

Minutes later, Heath was resworn to answer his allegations. Acknowledging their acquaintance, she related an altogether different set of conversations. “I have several times talked about it [Annesley’s reappearance], and said what a vile thing it was to take away the earl’s right, and that my lady never was with child; and I cannot say no more if you rack me to death.”

Turning to Hussey, she declared, “I never thought that you were such a man; I’ve heard people say that you were a gamester, and lived in an odd way, but I would never believe it till now. But I always took your part, and said you behaved like a gentleman.”

“I am a gentleman,” he insisted. “I can bring several people to justify me to be a gentleman, and a man of family; indeed I have heard you say it [i.e. that Annesley’s rightful inheritance had been usurped], and speak it with all the regret and concern imaginable.” 37

For the remainder of the day and all of Tuesday, more witnesses followed, rebutting as best they could pieces of the defense’s case. Thomas Higginson, a former surveyor for Baron Altham, swore to having seen Lady Altham, “big belly’d,” at Dunmain in the spring of 1715. A few charged the defense with soliciting perjured testimony, the most sensational instance involving an elderly Catholic priest by the name of Michael Downes, the member of an old Wexford family. According to the priest of a neighboring parish, Downes had accepted a bribe of £200 for swearing falsely to Annesley’s illegitimate birth—a grave sin for which he reportedly intended to seek absolution. (Of his accuser, Downes responded in court, “He is a vile, drunken, whore-master dog.”) Finally, at 6 p.m., both parties rested, with the court announcing that they would reconvene on Thursday the 24th, after a day’s respite.38

The trial’s penultimate stage commenced at eight o’clock with closing arguments by three counselors for either side. For eight hours, defense lawyers, led by the prime serjeant, Anthony Malone, recounted the testimony of the previous ten days. A prominent member of Parliament for County Westmeath, Malone was a polished orator. Along with other members of the defense, he expressed persistent surprise that the birth of a lawful heir had not attracted greater attention among neighbors and other members of the Annesley family. “It is impossible it should be a secret to all the world,” contended Malone, “except [for] two or three of the meanest servants.” Indeed, he asserted, not one person in the vicinity of New Ross worth more than £10 a year had testified to the boy’s birth. No more credible was Altham’s constant neglect of the child in Dublin. Such cruelty toward a legitimate son was inconceivable, as was the failure of John Purcell and Richard Tighe, among others, to bring the baron to account for his negligence. After all, “no man [was] more odious to the people generally [and] to people of power universally,” stated the solicitor-general, Warden Flood (if such harsh words about his late brother gave Richard pause, there is no report).

Vainly, however, did the defense rebut the two most glaring weaknesses in their case: Jemmy’s kidnapping and his subsequent prosecution for murder—“the only colours for this suit,” Malone claimed. “Were they out of the question,” he insisted, “I dare venture to say that this cause would be hooted out of court.” Flood likened the incidents to “a romantic cobweb.” All three counselors emphasized the enormity of the jury’s decision—“a cause, perhaps, of the greatest moment that ever was tried in a court of justice in this kingdom, and a stake of the greatest value that ever was in the disposal of any jury before.” Not only was the estate the largest ever contested in court, but numerous lives stood to be injured by a finding for the plaintiff, including those of countless tenants. Even more alarming was the potential danger to the social order. Personal property and the country’s system of inheritance, sanctioned by custom and the common law, stood imperiled should the plaintiff prevail, setting a precedent whereby every illegitimate son might be tempted to contest a lawful bequest. All the more reason, then, for the plaintiff’s evidence “to be proved beyond all contradiction.” Otherwise, asked Malone, “What family can be safe?” Echoed Flood, “Is not putting a suspicious man into a family, not only an injustice to posterity, but to the first founder of the family?” 39

After a half-hour’s refreshment for the jury, Serjeant Marshall rose to speak for the plaintiff. Straightaway he declared his belief that “there has scarce been an instance in any age of such a scene of iniquity, cruelty, and inhumanity as this.” Apart from reviewing the evidence on both sides, Marshall contrasted Annesley’s disadvantages in going to trial with the wealth and influence of his uncle. The passage of time had only compounded the difficulty of the task. After so many years, the serjeant wryly noted, “it is impossible for any man to keep his witnesses alive.” More surprising was the earl’s failure to produce a single member of his family to dispute the boy’s lawful birth. As for those witnesses whom the defense did call, “the most favourable construction,” argued Serjeant Philip Tisdall in his remarks, “is that they are ignorant of a fact so notorious to the rest of the country.”

Most important of all, testimony regarding Annesley’s kidnapping, a deed that “speaks stronger than words,” had gone uncontroverted, as had allegations respecting his prosecution. The uncle, “being of a proud avaricious disposition, tempered with cruelty,” proclaimed Marshall, “could not bear that a boy in those low circumstances should succeed to Altham’s estate and title, or be presumptive heir to the Earl of Anglesea.” It was an extraordinarily blunt indictment of a nobleman. At 10 p.m., the defense rested.40

Until their summations on Friday morning, the court’s barons had remained silent during much of the proceedings, except for ruling on the admissibility of John Giffard’s testimony. The chief baron, on occasion, had expressed dismay over the contradictory nature of the testimony and once admonished a defense witness for suggesting that the earl himself was James’s father. “This dirt will do the defendant’s cause no service,” scolded Bowes.

Judicial summations, while not critical in legal proceedings, frequently helped to guide a jury’s deliberations. The bench was obligated to identify the trial’s salient issues and to evaluate the relevant evidence, all the while clarifying basic points of law.

Bowes spoke first and at great length, followed by extended comments from Mountney. Although Dawson, the last to talk, took less than an hour, the three summations consumed most of the day. All noted the gross inconsistencies in testimony. Seldom, in all likelihood, had so many persons in a court of law lied so brazenly and with such apparent conviction. A witness for the defense, at the outset of her testimony, was seen to kiss her thumb rather than the Bible, only to have the oath administered a second time. “One or the other must speak false,” observed Bowes of the two camps; “which of them have done so, God only knows.” And, as a consequence, all three justices attached great weight to the known circumstances of the case—particulars that had emerged from the legal crossfire largely intact.

According to the common law, circumstantial evidence, in the absence of “positive proof,” was both a proper and necessary substitute as long as it led to a “violent” (extremely strong) “presumption” as to the act in question. “Light, or rash, presumptions,” William Blackstone later wrote, “have no weight or validity at all.”

One of the circumstances, in Bowes’s view, favoring the defense was the seeming ignorance of James’s birth among the distant relations of Lord and Lady Altham. On the other hand, Bowes laid great stress upon the youth’s kidnapping, adding, however, that Anglesea may have acted merely to avoid the “trouble he might have from this lad,” notwithstanding his illegitimate birth. For Mountney, however, both the prosecution and the kidnapping created a violenta presumptio that Annesley was his father’s lawful heir. Addressing the jury directly, the baron declared, “Witnesses, gentlemen, may either be mistaken themselves, or wickedly intend to deceive others. God knows, we have seen too much of this in the present case on both sides! But circumstances, gentlemen, and presumptions, naturally and necessarily arising out of a given fact, cannot lie.” In sharp contrast, Dawson stressed the implausibility of Annesley’s legitimacy, owing to witnesses able to contradict his birth at Dunmain. “You will consider,” the baron told the jury, “how far the transportation [to America] will make you give credit to a fact you should otherwise think improbable.” 41

The trial was the longest ever known in the British Isles. For twelve days, the jury had listened to testimony and diligently taken notes. They had been sequestered from family and friends, with the injunction to ignore anything that might be heard outside the courtroom. At long last, with the summations completed, the case was the jurors’ to decide as they withdrew to a nearby chamber late that afternoon.

As if on cue, Dublin’s weather had dramatically improved by the final week of November, reverting to the welcome warmth of summer, with a gentle breeze from the south and southwest. At 5 p.m., in less than thirty minutes, the jury had its verdict.

“Hear ye, hear ye,” proclaimed the clerk. “Gentlemen, which do you find, for the plaintiff or the defendant?”

“We find for the plaintiff,” announced the foreman.

That evening, as the Earl of Anglesea prepared to leave Dublin in disgrace, church bells pealed and bonfires lit up the streets. So quickly had word of the verdict spread, a newspaper reported, “all the streets seem’d to be in a blaze.” 42