The heirloom recipes in this book are reflective of Hyderabad’s ancient, multi-cultural history and before I give you more practical tips and pieces of advice on the recipes, I thought it might be interesting to delve into some history – of Hyderabad, and of our family.

What we recognize as Hyderabadi food today owes its origins to the Qutub Shahi dynasty which ruled over the erstwhile kingdom of Golconda for 169 years, from 1518 to 1687 before being conquered by the Mughals. Before the Qutub Shahi era, the region was ruled by the Kakatiya dynasty of Warangal and had also been a part of the Bahmani kingdom, which was based in Bidar that is now part of Karnataka. Sultan Mohammed Quli, a Qutub Shahi king, built Hyderabad in the 1580s, and was inspired by the beautiful, legendary Persian city of Isfahan. Poets, travellers, kings and common men alike sung praises of this new city, which though ruled by devout Shia Muslims, was very secular, multi-cultural and a haven for arts and literature. The Qutub Shahi rulers were also great connoisseurs of food and their cuisine married Turkish and Persian influences with local ingredients and culinary traditions.

When the Mughals defeated the Qutub Shahi rulers and staked their claim over the kingdom, they chose to move the centre of power from Golconda to Hyderabad and appointed a governor for South India, with the title of Nizam-ul-Mulk. Eventually, the governor’s title was changed by the Mughals to Asaf Jah, giving birth to the Asaf Jahi dynasty, which ruled over Hyderabad for two centuries, from 1724 to 1948, when the state was annexed by a newly independent India. The Nizams were, also, discerning gourmets and brought in culinary influences from Telangana, Marathwada and Karnataka.

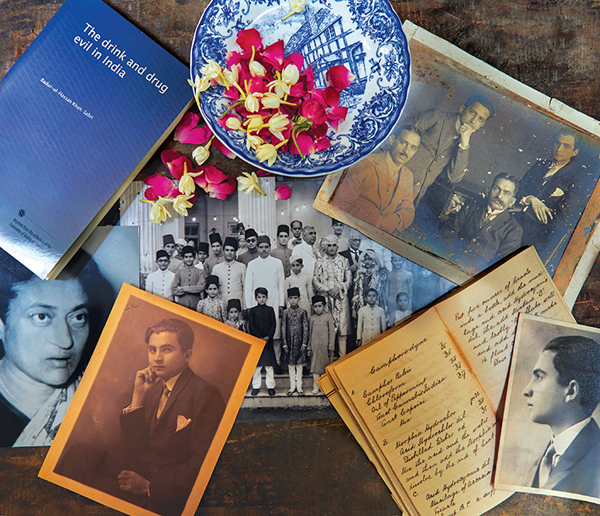

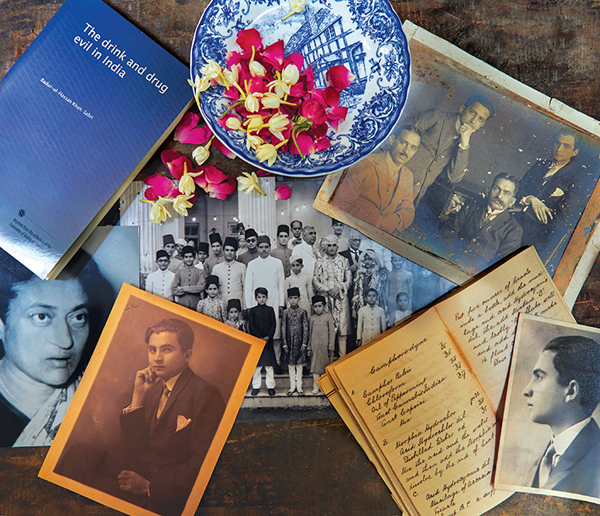

Our family, the Hassans, have been a part of Hyderabad’s history and played a role in India’s fight for independence. We have been told by older members of the family that when Peter’s father and his siblings were growing up, Hyderabad was a staunchly secular kingdom, embracing the traditions and cultures of all religions. Peter’s father, Syed Khurshid Hassan, was one of ten children born to Syed Ameer Hassan, a commissioner in Hyderabad under the Nizam’s rule, and his Iranian wife, Fakhrul Hajia Begum, who was from Shiraz. They were one of the first families to boycott British goods and burnt their British-made possessions in a bonfire in front of the family home, Abid Manzil.

At a time when aristocratic families patronized fine fabrics from Europe, the Hassans favoured Indian textiles. Peter’s grandmother, a strident and respected matriarch, was so staunchly anti-British that she sent her sons to Germany for higher education, and was an early supporter of the movement to spin and wear khadi. Three of Peter’s uncles – Badrul, Hadi and Abid Hassan – were particularly involved in the Indian independence movement. A close associate of Mahatma Gandhi’s, Badrul Hassan owned the first Cottage Industries Emporium in Hyderabad as well as the city’s first bookshop, The Hyderabad Book Company.

Hadi Hassan was a botanist and a scholar of Persian literature, while also playing a very important role in the independence movement, winning the admiration of leaders like Gandhi and Sarojini Naidu. He inherited a love of Persian from his Iranian mother and was decorated in 1960 with the Nishan-e-Danish of the First Order, which is Iran’s highest academic award. He also established a medical college at Aligarh Muslim University.

Abid Hassan, who was also known as Abid Hassan Safrani, was Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s personal secretary and interpreter. He took on the role out of admiration for Netaji’s revival of the Indian National Army, which had been set up in Japan by a group of Indian prisoners of war led by Captain Mohan Singh during World War II. He chose to add ‘Safrani’ to his name as a mark of communal harmony and is credited with creating the greeting ‘Jai Hind’ after Netaji requested him to think of a secular phrase that Indians could use as a mark of national pride.

For a family that was immersed in the politics and public life of the time, the Hassans retained their sense of humour and a great love for food, family and friendships. When I spoke with Peter’s cousins, Bizeth and Sanjar in Hyderabad while researching the book, they told me that while the men were illustrious and authoritative outside of the house, at home it was the women who commanded absolute respect.

From them, I have learnt that what makes Hyderabadi food so delicious and unique is the attention paid to every detail and technique, from marinating the meat and grinding masalas to the process of cooking, and then the garnishes, as well as how the dish is served. For example, the secret of a good saalan lies in the grinding of its masala, which must have the texture of silk. The stories of legendary hospitality and rich feasts are far too many to recount, and we have attempted to retain that vibrant spirit of the family through the recipes in this book.