4

Universal Jurisdiction: The Proceedings against Augusto Pinochet

A jurisprudential bombshell

General Pinochet grabbed the world’s attention in October 1998, this time not as the author of a bloody coup but due to his unexpected arrest in a London clinic. The former Chilean president ceased to be the director of operations, and instead became a bystander who for 503 days awaited his fate at the hands of Spanish and British judges and senior politicians. During this lengthy hiatus, politics and law became closely intertwined, eventually producing an outcome that would have serious implications not only for human rights in Chile, but also at a global level in the fight against impunity for heads of states. Rarely is the indictment of the former dictator described without the epithets ‘landmark’ or ‘historic’; one commentator has even described it as a ‘jurisprudential bombshell’ (Falk, 2009: Ch. 7), given that never before had a former head of state been arrested abroad on the grounds of universal jurisdiction. The Pinochet proceedings are therefore a key starting point for considering what has become an important component in the emerging international criminal justice system: trials in foreign courts under the principle of universal jurisdiction. This was a case where indictments for human rights crimes were impossible at the domestic level, due to a general amnesty and the reluctance of judges to prosecute, and foreign courts therefore provided an alternative arena for trial.

The proceedings against Pinochet forced jurists in Spain, the UK and several other European countries to confront head on uncharted questions of international criminal law; among them, the potential of foreign courts to act as a forum for trying perpetrators of heinous crimes committed thousands of miles away; the limitations to the impunity granted to a former head of state; and the scope of interpretation of the principle of universal jurisdiction in domestic courts. The decision of Spain’s Audiencia Nacional and the final ruling of the House of Lords both made it clear that former dictators could no longer expect an automatic safety blanket for human rights violations committed while in power, at least not when they left the confines of their own countries. The principle of individual accountability for heinous crimes began to take on practical significance.

The Pinochet case also invited serious objections, first and foremost concerning the right of foreign courts to meddle in another state’s delicate process of transnational justice. Many were outraged by the decision of the British authorities to arrest Pinochet for the challenge that it represented to state sovereignty. The reaction of the Chilean president at the time, Eduardo Frei, on hearing of the arrest, was to ask why, if the Spanish judges were so keen to prosecute heinous crimes abroad, had they not done so in relation to abuses committed during Spain’s own civil war between 1936 and 1939?1 It seemed as though double standards were being applied, with one set of laws for national crimes and another for extra-territorial crimes. Henry Kissinger was among the indictment’s most fervent critics, and he attacked the precedent for threatening to undermine Chile’s democratic reconstruction. He argued that ‘the instinct to punish must be related, as in every constitutional democratic political structure, to a system of checks and balances that includes other elements critical to the survival and expansion of democracy’ (Kissinger, 2001: 91). Were the fears expressed by Kissinger really well-founded in the case of Pinochet? Are transnational trials damaging to the reconciliation of a nation after a particularly fraught chapter of internal violence? Or, on the contrary, can foreign courts act as a catalyst for domestic justice and thus for a more complete process of truth and reconciliation?

This chapter will focus on the political ramifications of the Pinochet case and the role of the extra-territorial proceedings in reopening the discussion about the past at a national level. With General Pinochet’s absence from the country, his grip on national politics loosened and the possibility of a new perspective on human rights was opened up. The political winds shifted and new state and non-state actors were empowered; victims, human rights groups and judges all played a major role in advocating a new approach to transitional justice. The case also had an impact at the global level in terms of human rights advocacy and accountability, although the long-term potential for challenging impunity through universal jurisdiction is uncertain now that national legislators have seriously curtailed the scope of extra-territorial laws.

Figure 4.1 Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, 1976

Credit: Wikicommons

Testing the limits of universal jurisdiction

A pacted transition

The news of the coup d’état that deposed Chile’s first democratically elected socialist leader, Salvador Allende, on 11 September 1973, and resulted in his subsequent death at the presidential palace of La Moneda, stunned the world. Congress was dissolved and a military junta was established. The years which followed were marked by brutal killings, torture and disappearances which forced General Pinochet’s opponents into silence. An estimated 3,065 individuals died from political persecution during the seventeen-year dictatorship (National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture, 2011), but the number of Chileans who went into exile was far greater. Almost 200,000 people were forced to leave the country and many settled abroad permanently.

The worst period of human rights abuses occurred at the start of the military regime, between 1973 and 1977. The notorious Chilean secret service, DINA, was established towards the end of 1973 and initiated an organised method of political persecution, with left-wing activists as its main targets. The military government did not deny the existence of human rights violations, but justified its actions on the grounds that the country was on the verge of a civil war. In 1978 the military junta issued a self-amnesty absolving all its agents responsible for crimes committed from 1973. To this day the amnesty remains in place, although judges have found ways to circumvent it.

In 1990 General Pinochet stepped down from power following a referendum in which 54.7 per cent of the population voted against the prolongation of his rule.2 But the return of democracy did not mean the disappearance of Pinochet from politics; a pacted transition ensured that the military was granted an important role in many aspects of public life. As part of the deal with the new democratic government, the former head of state continued as chief of the armed forces until 1997. He was then named a lifelong senator, a role which under Chilean law granted him impunity. Key supporters of the military dictatorship kept their positions in public office, including in the courts.

As in the case of other countries struggling to overcome years of dictatorship, the new president, Patricio Aylwin, was confronted with the key question of how best to achieve reconciliation and the consolidation of democracy. Chilean society was, and still is, divided, so any attempt to reconstruct the country had to avoid exacerbating the existing polarisation. A considerable proportion of Chileans still supported Pinochet when he stood down, as shown by the fact that 43 per cent of the country voted to keep him in power in the 1988 plebiscite. Any successor therefore had to tread softly over the eggshells of the past. Argentina’s approach of putting the country’s highest-ranked military officers on trial in the mid-1980s persuaded the Aylwin administration to be more cautious in dealing with the past and to avoid outright prosecution.

In 1990, the National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation was established to investigate the human rights violations during the Pinochet years. It produced a tentative report, known as the Rettig Report (1991) after its chairman, which named the regime’s victims but not the perpetrators. For most of the 1990s, Chile’s strategy of reconciliation was based on no more than offering victims material reparations in the form of public health provision, pensions and education grants for the damages inflicted upon them, rather than through the legal channel of holding the perpetrators accountable. There was a total lack of political will on the part of the post-dictatorship governments to delve any deeper; one significant illustration of this tacit acceptance of the status quo is the fact that National Liberation Day, celebrating the 1973 coup, was not abolished until 1998.

Unwilling to challenge this political climate, the judiciary closed most cases relating to human rights violations during the dictatorship. A few prosecutions did take place in the early 1990s, but they targeted only a tiny minority: by 1999, although more than 5,000 lawsuits had been filed, only nineteen former members of the military had been convicted of crimes during the Pinochet era, and almost all of these were low-ranking officials indicted for offences that were not included in the amnesty (Chinchón Álvarez, 2007). For most of the 1990s therefore, national justice was able to reach only the small fry; the prospect of bringing Pinochet to account seemed a very long way off.

The proceedings in Europe

In many ways, the arrest of Augusto Pinochet in London came out of the blue. The proceedings were initiated as a symbolic struggle more than anything else. For years, a sprinkling of human rights groups and members of civil society had been fighting for the crimes under Pinochet’s military dictatorship to be recognised, but the calls fell on deaf ears as the government and society at large seemed intent on forgetting this chapter of Chile’s history. So what was the detonator for the Pinochet case in 1998? Among the main ingredients were a handful of extremely determined judges and the strong backing of a transnational network of human rights organisations prepared to work insatiably to see Pinochet stripped of his immunity. The principal countries that were to have a bearing on the General’s fate were Spain, the United Kingdom and Chile. The drama unfolded initially in two main theatres, Spain’s Audiencia Nacional and the British House of Lords, although allegations were also brought against the military dictator in France, Belgium and Switzerland. So divisive was the case that it had to be re-heard in three separate phases of litigation by the House of Lords, the UK’s highest court of appeal at the time.

The political climate in these three countries was somewhat favourable for the proceedings to run their course (Roht-Arriaza, 2005). Both the British and Spanish governments were forced to choose between the obligation to uphold a professed commitment to human rights and international conventions on the one hand, and the prospect of damaging relations with a strong economic and former strategic power, Chile, on the other. In particular the UK had important arms deals with Chile, which in part explained why Pinochet travelled to London in 1998. However, the fact that the three governments at the heart of the proceedings were fairly centrist and committed to upholding due process allowed the lawsuit to run its course. In Spain, the right-wing People’s Party (PP) was keen to show the complete independence of the judiciary, especially as its actions were being so closely scrutinised by the Spanish public and press, who for the most part were in support of seeing Pinochet stand trial. In the UK, the Labour government under Tony Blair wanted to be seen as adhering to its so-called ‘ethical’ foreign policy. It would have been a very different story, for example, had Pinochet come to the UK a decade previously as a firm friend and ally of Margaret Thatcher. The former Conservative prime minister repeatedly called for the General’s release and as a gesture of solidarity even paid the former president a visit when he was under house arrest.3

In 1996, the first case of extra-territorial crimes was filed in Spain and concerned victims of the military regime in Argentina during the 1970s. The judge leading the investigation was Baltasar Garzón, who had already made a name for himself with the prosecution of Spanish state terrorists and drug traffickers. Victims of the Chilean dictatorship were keen to jump on the bandwagon, and an initial complaint against General Pinochet was filed by Juan Garcés, a lawyer with deep ties to Chile, and Manuel Murillo, representing the Salvador Allende Foundation. Several human rights organisations, including the Chilean Association of Family Members of the Disappeared (AFDD), were also instrumental in bringing the case to Spain. Among the alleged crimes were genocide, terrorism, torture and illegal detention from 1973 to 1990. Initially filed separately, the Argentinean and Chilean cases were eventually assimilated into a broader investigation, headed by Judge Garzón, into Operation Condor, a regional strategy aimed at obliterating left-wing opponents across Latin America in the 1970s.

So why were these initial complaints filed in Spain? In addition to close cultural ties and the fact that many political exiles had fled to Spain during the military dictatorship and established human rights networks there, the peculiarities of the Spanish legal system facilitated a judicial process which in other countries might have proved impossible (Roht-Arriaza, 2005). Spanish courts had the jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute extra-territorial crimes such as genocide and terrorism, or any crime that Spain had an obligation to prosecute under international treaties. The victims concerned did not necessarily have to be Spanish nationals, thus leaving a large window for investigating cases of extra-territorial human rights violations. Furthermore, under Spanish law, ordinary civilians can file a case through a procedure known as a popular action (acción popular), without having to prove a direct connection to the victims or incur costs. In the initial stages, the support of the public prosecutor is not required; a magistrate prepared to pursue the case is enough. This unusual feature allowed Judge Garzón to move forward with the investigations into Operation Condor despite the opposition of the public prosecutor. There was, however, one seemingly crucial obstacle under Spanish law: no trials are permitted in absentia. If any generals from the Southern Cone were to stand trial, they would have to be brought to Spain.

This explains why, when the news broke that Pinochet was travelling to London for a medical operation, events accelerated rapidly. Faced with the possibility of Pinochet once more returning to the safe haven that Chile’s justice system granted him, Judge Garzón decided to issue a warrant under the British Extradition Act. On the night of 16 October 1998, General Pinochet was arrested at the private clinic where he was receiving treatment.

The Audiencia Nacional’s public prosecutor, Eduardo Fungairiño, rapidly challenged Judge Garzón’s extradition warrant before the Spanish court. However, he lost his case when, at the start of November, the court’s eleven judges unanimously upheld Spain’s right to exercise universal jurisdiction, specifying that the country had a legitimate interest in hearing the case since more than fifty nationals had been murdered or disappeared in Chile.4

Meanwhile in Britain, Pinochet appealed Spain’s decision. The General’s lawyers pointed out a technical problem with Garzón’s warrant: the detention of Pinochet was for the crime of genocide, which is not an extraditable offence under British law. Under the rule of double criminality, extradition can only be sought when a crime is prosecutable under both the law of the requesting state and that of the state where the fugitive has taken refuge. The Spanish judge therefore issued a new warrant, this time for acts of torture and hostage-taking. But a British court quashed this on the grounds that Pinochet, as a former head of state, enjoyed absolute immunity from prosecution under British jurisdiction. The Crown Prosecution Service, representing Spain, appealed the decision and the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords was called upon to hear the case. The appeal court tended to deal with cases swiftly, but with the principle of universal jurisdiction at stake, the proceedings against the General involved three separate phases of litigation known as Pinochet I, Pinochet II and Pinochet III (see Figure 4.3).5

Figure 4.2 London rally urging the extradition of General Pinochet after he was arrested in London, October 1998

Credit: Carlos Arredondo

Figure 4.3 Justice abroad: the Pinochet proceedings in Spain and the United Kingdom (1998–2000)6

The principal issue at the first set of hearings was whether Pinochet, as a former head of state, enjoyed sovereign immunity from arrest and extradition proceedings in the United Kingdom. Since Pinochet was in power during the period of the alleged crimes, the Law Lords considered whether these could be deemed part of his official functions, or whether they fell outside of the scope of his duties. On 25 November 1998, with a vote of three to two, the House of Lords ruled that acts of torture, hostage-taking and crimes against humanity went beyond the ambit of his official functions, and therefore that Pinochet could not be granted immunity from extradition for these crimes. Although a close battle, it was a momentous ruling in relation to the principles of individual accountability and universal jurisdiction. In his opinion, Lord Nicholls clearly asserted that the principle of sovereignty does not shield political leaders from prosecution for heinous acts:

International law recognizes, of course, that the functions of a head of state may include activities which are wrongful, even illegal, by the law of his own state or by the laws of other states. But international law has made plain that certain types of conduct, including torture and hostage taking, are not acceptable conduct on the part of anyone. This applies as much to heads of state, or even more so, as it does to everyone else; the contrary conclusion would make a mockery of international law.7

By contrast, the two judges presenting the dissenting view argued that Pinochet was acting in a sovereign capacity, and expressed scepticism about the implementation of universal jurisdiction.

In accordance with British law, however, it was Home Secretary Jack Straw who was obliged to have the last word as to whether Pinochet should be returned to Chile or sent for trial in Spain. By sending him back to Latin America, the government risked breaching the UK’s commitment to the principles of international law, but by denying such a move, the country faced uncertain diplomatic consequences as the United States and Chile were both exerting strong pressure for the defendant to be returned home.8 Despite this pressure, Straw maintained that legal questions rather than political matters should decide the case.

While human rights’ advocates lauded the Law Lords’ decision, the principle of judicial independence was questioned in Pinochet II. It emerged that one of the five Law Lords was a director of the Amnesty International Charitable Trust, thus raising the question of his possible bias, since the NGO had acted as an intervener in the first set of hearings. Automatic disqualification had never before been the result of non-pecuniary motives, but the case was too important to ignore the charge of unfair justice. A new panel was convened comprising seven Law Lords who had not previously been party to the case.

The third phase of litigation, in contrast to the first, focused on much narrower technical issues relating to UK law rather than to international customary law. On 24 March 1999, after several weeks of deliberation, six of the seven judges handed down a judgment upholding the decision to deny Pinochet immunity. However, the court concluded that all crimes filed against General Pinochet prior to 29 September 1988 – the date when the International Convention against Torture was incorporated into British law – did not constitute extraditable crimes. In this way, important limitations were imposed on the number of crimes for which Pinochet could be extradited.

Commentators have pointed to the final ruling as representing, from a political standpoint, a shrewd decision, in which the Law Lords attempted to placate all those involved in the narrowest possible terms (Roht-Arriaza, 2005). At a time of serious legal shakeup in Britain, an overturning several months later of the decision made in the first hearing would have seriously undermined the credibility of the British legal system (Byers, 2000). Therefore the final ruling, which recognised the limits of Pinochet’s impunity but in concrete terms found him extraditable for just a small percentage of the initial allegations, was a practical compromise.

But this was not quite the end of the story, and the case would after all come to rest on politics rather than on the legal hearings. Determined to see Pinochet brought back to the country, the Chilean government finally got its way. After the General’s medical condition had deteriorated somewhat, the British government allowed the former president to undergo a medical inspection. British doctors declared Pinochet unfit to stand trial and he was released on humanitarian grounds at the start of March 2000. His health would be the subject of intense debate over the next few years, with his opponents claiming he had feigned illness to escape extradition. He was even awarded a symbolic Oscar for his performance by protesters in Santiago.9 In the end, General Pinochet was not to become the first head of state to stand the test of universal jurisdiction in a European court, but neither would he find himself as sheltered from justice as he had once been.

Bringing justice home

A new climate of transitional politics

When Pinochet landed in Chile on 3 March 2000, among the first words he said to his son Marco Antonio were ‘the air is different here’.10 Although it was an expression of joy at having returned to the more favourable climate of his home country, the General would soon find that the air had undergone profound changes in the months of his absence. After years of obscurity, the claims of the victims had entered the public realm for the first time, and Pinochet’s power and peace were now shattered by the number of court cases that had stacked up against him. As the New York Times put it, Pinochet returned to Chile as the ‘emperor with no clothes’.11

Transitional justice in Chile can be time-lined into two separate phases (Collins, 2010; 2013). The first, between 1990 and 1998, was a static period during which justice, in the words of President Aylwin, was done ‘to the extent possible’12 through a national truth commission, the Rettig Commission, while avoiding human rights trials. It was very much a period of forgetting and moving on, of restorative justice with a curtain drawn over the past. This approach was influenced by the argument of transitional justice theorists that human rights trials were destabilising to the consolidation of transitional democracies (Huntington, 1991). According to this view, prosecutions were counterproductive – and even threatening – to the rebuilding of institutions and society. The very real fear of another coup meant there was very little retributive justice in the decade following Pinochet’s resignation. The Rettig Commission was conservative, failing to address the issue of torture for the survivors of the regime, while the amnesty was firmly entrenched, with judges reluctant to challenge it. Pinochet’s sway over politics was still tight in these years.

The year 1998 was therefore a turning point, after which the non-judicial mechanisms in place were no longer deemed sufficient for a full reckoning with the past. In this second phase of transitional justice, prosecutions since Pinochet’s arrest have not been a total success, with ‘a rough kind of justice’ being done at a national level (Roht-Arriaza, 2005: 96); statutes of limitation have prevented some cases from being heard; and the amnesty law continues to be a clear hurdle. Nevertheless, since 1998 the search for individual criminal accountability has gained significant momentum, and a broader approach to transitional justice combining retributive sentences and renewed truth endeavours, as well as symbolic measures of reparation, has been adopted.

Pinochet’s arrest seems like the clear-cut division between the two periods of transnational justice, but the merit for initiating the second phase cannot solely be attributed to external agents since significant developments were already occurring at a national level (Pion-Berlin, 2004). In the mid-1990s, reforms concentrated on creating specialised chambers to hear appeals on closed cases and on establishing a new relationship between civilian and military courts. The number of judges in the Supreme Court rose from seventeen to twenty-one, and there was a change in its composition. With eleven new judges incorporated by the end of 1998, the majority of Supreme Court judges had been appointed after Pinochet’s time in office. The change in the composition of key judicial organs meant the gradual loosening of judges’ loyalty towards the military and a greater willingness to proceed with human rights trials.

There were several other significant developments in early 1998 prior to Pinochet’s arrest, including a lawsuit directly implicating the General in human rights violations and a Supreme Court ruling on how to tackle the issue of the ‘disappeared’ during the military regime.13 At the start of 1998, Judge Guzmán began investigating the crimes committed by the ‘Caravan of Death’, the special military unit in charge of hunting down political opponents in the regime’s early days (Verdugo, 2001). For the first time ever, General Pinochet’s name was linked to several of these crimes, and although he still enjoyed parliamentary immunity at the time, the case would eventually lead to his indictment in December 2000, an event which for many years had proved unimaginable. In another ruling a month before Pinochet’s detention in London, the Chilean Supreme Court ruled in favour of reopening a case, the Poblete Córdova proceedings, concerning the disappearance of a left-wing activist during the dictatorship. As well as stating Chile’s obligations under international treaties, the ruling was crucial in providing a way to circumvent the 1978 amnesty laws. It considered that for the amnesty to be applied, the whereabouts of the victim had to be known; otherwise a ‘disappearance’ constituted an ongoing crime which could be investigated.

These significant advances at a national level cannot, therefore, be excluded from the picture. But the international community’s sudden attention on Chile provided a much-needed impetus in the fight for accountability; with foreign governments watching to see whether Chile would uphold its professed commitment to justice, the government felt ashamed and pressured its own courts into delivering justice (Pion-Berlin, 2004).

Pressure from outside was accompanied by intensified action by civil rights groups within Chile. Thousands of protesters took to the streets of Santiago demanding that General Pinochet be put on trial. The proceedings abroad helped empower victims, granting them an important voice in the public sphere. With the developments in Europe, human rights groups, such as AFDD and the Association of Families of Executed Political Activists (AFEP), regained a prominent role by providing evidence for Pinochet’s indictment.

Addressing human rights abuses in Chile

So what, in concrete terms, was done to tackle human rights abuses under Pinochet’s military rule? One of the most significant moves, initiated under the government of Ricardo Lagos, was the creation of a second truth commission.14 Between 2003 and 2004 the Valech Commission investigated political imprisonment and torture. In contrast to the first truth commission of the early 1990s (which produced the Rettig Report), the Valech Commission was instructed to identify the survivors of the military dictatorship (as opposed to only the dead), as well as the methods used and the locations of torture chambers. The Commission did not altogether abandon the cautious approach of the early years: a law of secrecy protected testimonies, which could not be used in trials for fifty years, and torture victims were only recognised as such when they had suffered physical abuse in political prisons, rather than in their homes or temporary detention centres. But despite its limitations, the Valech Commission successfully identified more than 28,000 victims of the military dictatorship, including children, the elderly and women (National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture, 2004).

The Pinochet effect was not just a short-term attempt by the Chilean government to satisfy spectators abroad; confronting the human rights abuses of the military dictatorship has become a definitive obligation for the country’s government. This has occurred, according to Collins (2013), not because the executive has been an active architect in tackling past violations, but thanks to the interaction between accountability actors and justice institutions.

Governmental measures to address the Pinochet years have included the passing of legislation of symbolic and economic value and the creation of sites of remembrance. Two initiatives of note were the opening of the National Institute for Human Rights in 2010 and the inauguration of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago de Chile during Michelle Bachelet’s first presidency. The museum has been visited not only by political figures who have always declared themselves against the military dictatorship, but also by right-wing politicians such as former president Sebastián Piñeda, indicating a new political climate. As human rights lawyer Roberto Garretón pointed out, the museum has provided a vital collective space for remembrance: ‘This museum is a step in the positive direction for the reconciliation between the Chilean State and the victims.’15

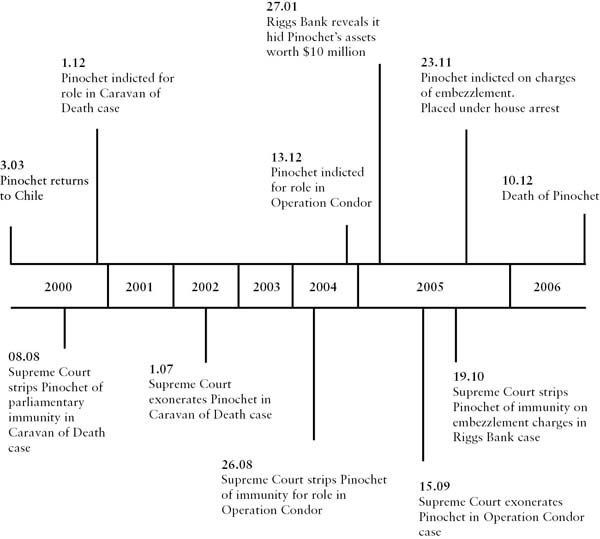

This political shift provided a new impetus for the judiciary to prosecute, starting with Pinochet himself. Judge Guzmán was the first to file a petition to have Pinochet’s immunity lifted on 3 March 2000, the same day the General returned to Chile. Many were sceptical both within and outside Chile about the chances of breaking Pinochet’s shield of impunity. But this scepticism was initially dispelled when, in August 2000, with a vote of fourteen to six, the Supreme Court stripped the General of his immunity. A few months later, he was formally indicted for participating in eighteen kidnappings in the Caravan of Death case. His immunity would be removed a number of times between 2000 and 2006, but legal proceedings suffered a rollercoaster ride over the next few years, as he was released on several occasions on the grounds of ill health. Added to the various human rights cases, he was indicted in 2005 for embezzlement, after the US Senate revealed he had stashed millions of dollars in offshore accounts with Riggs Bank. This was a major political blow, as his supporters found it increasingly hard to defend a corrupt man (Roht-Arriaza, 2009). Figure 4.4 shows a timeline of the most important cases brought against General Pinochet, including the indictment for his role in the Caravan of Death and Operation Condor. He would never stand trial by the time of his death on 10 December 2006, but by then his image had been seriously discredited.

Figure 4.4 Justice at home: proceedings against Pinochet in Chile (2000–06)

Lawsuits against other key figures of the military regime have been similarly stop-go processes with mixed successes. There have been important convictions such as that of Manuel Contreras, the ex-head of the secret police DINA in 2006, and the conviction in 2013 of eight military officers for their role in the murder of fourteen detainees in the Caravan of Death case. But a Human Rights Observatory at the University of Diego Portales (Observatorio DD.HH., 2014) highlights a number of reverses in human rights prosecutions between 1990 and 2014, due in large part to inconsistencies in the interpretation of the law. Among the major obstacles to cementing accountability for crimes committed during the dictatorship are the sharp differences in the Supreme Court over statutes of limitations and the application of international law principles. The lack of consensus on these legal questions means that verdicts are dependent on the composition of the Court on the day, which is hugely frustrating for victims. Faced with these conditions, several victims have chosen to appeal their case at the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) over Chile’s failure to investigate and to make reparation for acts of torture. Obstacles remain on the political front too. The biggest sore is still the 1978 amnesty law, which has not been overturned despite this being a key promise made during President Bachelet’s election campaign. The Pinochet proceedings had an impact in modifying perceptions of the dictatorship, but there are still very visible fractures from that period being played out along political lines today.

Global impact of the proceedings

The Pinochet case clearly captured the imagination of the public across the globe. Chile had for a long time been of interest to Europeans due to its democratic traditions resembling Europe’s political spectrum with a clearly defined left and right, in contrast to other Latin American countries with a stronger populist tradition. There was genuine shock when the coup d’état brought Chile’s long-standing democratic tradition to an abrupt halt. When Pinochet was arrested in October 1998, public opinion was quickly mobilised. Chilean exiles, as well as members of the British and Spanish public, took part in anti-Pinochet demonstrations, while others backed pro-Pinochet marches; the media also got fully on board, perhaps because there were few other gripping stories to report at the time (Byers, 2000). The drama was well-documented in public broadcasts, and for the first time in British history a Law Lords’ decision was shown on live television. Public interest in the case was such that while Jack Straw was considering his final decision regarding Pinochet’s release, more than 70,000 letters and emails were sent to the Home Secretary (Roht-Arriaza, 2005).

Similarly to what occurred in Chile, the Pinochet proceedings empowered victims across the world to initiate lawsuits against perpetrators of heinous acts. Victims began to look for justice alternatives beyond their own borders, many following the Pinochet path of transnational prosecutions. The structural characteristics of transnational prosecutions, which rely heavily on testimonies and the gathering of evidence from victims, as opposed to the ‘top-down’ strategies adopted by prosecutors, have given survivors a crucial role in the fight for justice. Judges and lawyers are also of fundamental importance in making trans-border prosecutions possible. According to Ellen Lutz and Kathryn Sikkink (2001), transitional prosecutions are not the result of a natural evolution of international criminal law; rather, they are the product of individual figures – judges and human rights lawyers, the so-called ‘norm entrepreneurs’ – pushing the boundaries. In Spain, Judge Garzón proved to be one such ‘norm entrepreneur’, and in Chile Judge Guzmán’s interventions were important in testing the limits. They inspired others around the globe to challenge the scope of international law.

Several cases brought before Spanish, Dutch and Belgian courts at the end of the 1990s seemed to have been a direct result of the Pinochet case; in particular those of Hissène Habré of Chad, Desiré Bouterese of Suriname, Abdoulaye Yerodia Ndombasi of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Efraín Ríos Montt of Guatemala (Roht-Arriaza, 2005). Activists realised the potential of universal jurisdiction in Europe for putting leaders from powerful countries on trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Lawsuits were also filed against sitting heads of state including Ariel Sharon and George W. Bush. The cases filed resulted in a few landmark sentences, such as that of Adolfo Scilingo, the ex-Argentinian navy officer, who was convicted in 2005 by Spanish courts to 640 years’ imprisonment for crimes against humanity. But it soon became clear that the Pinochet precedent was not going to open the way for easy extra-territorial justice across the globe. On the contrary, European governments became wary that generous laws on universal jurisdiction could lead to an avalanche of similar requests from across the world and create tricky diplomatic situations.

As a result, national legislators have placed more stringent limits on the exercise of universal jurisdiction. Spain and Belgium have imposed greater conditionality on its application, in effect linking the principle to nationals or residents and abolishing the possibility of appeal in cases which have been dismissed. The United States exerted much pressure on Belgium to repeal the country’s universal jurisdiction law in 2003, with Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld threatening to pull NATO headquarters out of the country if the Belgians did not comply (Anon., 2003; Halberstam, 2004). Likewise, Spain placed new limits on universal jurisdiction in both 2009 and 2014 after diplomatic pressure was exerted by Israel, China and the United States to reduce the scope of its laws (Langer, 2011). Spain’s second reform on universal jurisdiction came shortly after the Spanish authorities had released an arrest warrant in November 2013 against five Chinese officials who stood accused of participating in genocide against the Tibetan people.16 The upshot of these reforms has been the virtual removal of universal jurisdiction from the Spanish legal system (Alija Fernández, 2014). In such ways, justice for the victims of heinous crimes has often been traded for political and diplomatic interests.

A parable for universal jurisdiction

If measured by the delivery of a final sentence, the case of Augusto Pinochet would seem like an abysmal failure. The General died peacefully at home in 2006, without having been convicted by either European or Chilean courts. But although Pinochet never faced trial, the proceedings against him achieved what few other international criminal trials have: the discrediting of the dictator’s name and a new approach to dealing with crimes committed during his dictatorship. Whereas in the years immediately following Pinochet’s relinquishing of power the demands of individual victims in Chile were largely ignored in favour of the wider project of democratic reconstruction, this absolute trade-off is no longer deemed satisfactory, nor in fact successful, in healing the wounds of the past (Landman, 2013). The Pinochet case had the effect of accelerating a new stage in transitional politics in which there was a notable shift in notions of individual criminal responsibility and a new relationship between the state, the judiciary and the victims of the military dictatorship. Successive Chilean governments have been forced to adopt a more extensive human rights agenda and have multiplied the number of symbolic and economic reparation measures. In parallel, the judiciary has been more willing to prosecute, although justice remains unpredictable and partial, with victims continuing to look towards European and inter-regional courts in the absence of decisive verdicts at home. These changes were propelled from the bottom-up, by civil society along with judges determined to challenge the status quo of impunity which had dominated during the early transition to democracy.

At a global level, the case of Augusto Pinochet constituted a pioneering example. Civil society had defied the Chilean state and territorial confines by bringing the case against Pinochet to a global audience. This in turn empowered victims all over the world, from Guatemala to Chad, to challenge the impunity of perpetrators of human rights violations in foreign courts. But despite the possibilities that universal jurisdiction seemed to be offering at the turn of the century, its scope has since been limited, with few heads of state, present or past, actually tried abroad. Does this mean that universal jurisdiction’s brief heyday has already come to a close? The conviction of Hissène Habré by the Extraordinary African Chambers in Senegal in May 2016 shows that it still has the potential to deliver justice in the face of impunity, if very late in the day. It may even have transformed justice in Africa.17 But the world’s most powerful countries – most significantly the United States and China – still have enough influence to shield themselves from the ramifications of universal jurisdiction by exerting strong pressure on foreign governments to change their laws. Their campaigns have succeeded, such that the prospects of seeing powerful leaders tried on the principle of universal jurisdiction are more limited today than they were at the turn of the century.