This summer I have spent many afternoons near the Louvre, in the Jardin des Tuileries, lying on the scorched grass, looking at the statues. I am not sure which mythical or biblical characters are depicted (though I guess that the one in chains might be Prometheus). My appreciation of the statues would be greatly improved, I am sure, by some kind of mythological guidebook or commentary, but even without one, the essential concerns of the statues are obvious: punishment and suffering, agony and ecstasy.

Tourists look up at the statues and photograph them. Sightless, the statues never return their gaze. In classical tragedy, blindness is a frequent affliction, and in the Tuileries, too, some of the statues seem either to have been blinded or—and it amounts to the same thing—to have been condemned to the lidless torment of never shutting their eyes.

Those who sentenced the statues to their varied fates—the gods? their sculptors?—have gone. Only the statues and the indifferent sky remain, endure. Always, in some way, the figures are resisting, or trying to rise. One—Prometheus?—strains against his chains, against gravity, toward the sky. This sense of strain is so great that the statues seem to be struggling to free themselves of the stone in which they are cast. The medium through which they strain to free themselves is the body in which they are imprisoned.

The statues are immersed so completely in their exertions that the rest of us, even those who jog past in shorts and trainers, seem engaged in a form of more or less active lolling. This is what gives the figures their enduring appeal.

In late August, with the sun blaring from a soundless sky, the World Athletics Championships begin. I have borrowed a television, and reception is poor; there is no aerial, just a coat hanger jabbed into the back of the set. The commentary is in French, and I understand little of what is said. Still, grateful to have a TV at all, I peer through a molecular buzz of snow as athletes strain to defy gravity, to push back the limits of the physical. Lacking the context-forming commentary, I watch Carl Lewis break the 100-meter record. Katrin Krabbe wins both the women’s sprints. In the final leg of the 400-meter relay, Kriss Akabusi charges past Antonio Pettigrew…

What with the poor picture quality and the French commentary, I am often unsure of exactly what is happening (contrary extremes of passion—tears and laughter, rage and celebration—curiously resemble each other) and so, each morning, I buy an English newspaper to check what occurred the day before. The morning after the 100-meter final, it was reported that, in post-race interviews, Lewis had cried several times when mentioning his dead father. A few hours before the race, Leroy Burrell, who came in second, had received news that, following heart surgery, his father had come out of intensive care. Drawn two lanes to the left of Lewis, he did not have a clear view of his rival because he is blind in his left eye. The article is accompanied by a photograph of all eight runners as Lewis crossed the line, arms raised in triumph and vindication.

For every image of triumph like this, however, there is one of dejection, for the strength and power of athletes coexist with extraordinary fragility. Jackie Joyner-Kersee falls and sprains her ankle in the long jump, crashes to the floor in her sprint heat; Steve Cram strains a groin—not in training but while he is getting off a train. The athlete’s body is a precipice, and victory involves advancing close to—and even, for Ben Johnson or boxer Johnny Owen, beyond—its edge.

I don’t know, but I suspect that the statues in the Tuileries are not particularly outstanding pieces of sculpture. If this is the case, then they reveal how, at certain moments in the tradition of any art, the expressive potential of the average can exceed that of the outstanding at earlier or later dates. Nowadays, for example, the human form cannot so readily be coaxed into such impressive attitudes; only an exceptional artist today could achieve the power routinely managed by the sculptors whose work is displayed in the Tuileries. (In sport the opposite is true: most top athletes now surpass the record-breaking feats of thirty years ago.) Partly this is because of internal, art historical exhaustion; but it is also because the hunger that such sculptures sought to assuage is now satisfied by sport. More precisely, sport both answers and simultaneously exacerbates that need in such a way that it is incapable of being satisfied by carved or molded stone. Most obviously, the increasingly sculpted bodies of athletes have now gone beyond the ideal that once could only be achieved in stone (the posing of boxer Chris Eubanks and the strength-sapping stillness and balance of gymnasts make this point literally). More broadly, in the age of mass media, only images of war and famine offer a starker revelation and depiction than sport of the human body in extremis as key moments are slowed down, expanded, replayed, and, ultimately, frozen. This enables us to dissect visually athletes striving to burst free of the confines and limits of the body. In slow-motion and close-up, the fleeting glimpses of straining sinews, swollen muscles, even that strange bobbing of the sprinter’s lower lip, are revealed and preserved. What remains of the 100-meter final, or Akabusi’s lunge for the line, is a succession of slowed or frozen moments, of photographs. Long after the event is over and the cameras have departed, the athlete remains captured in passed time, like a statue.

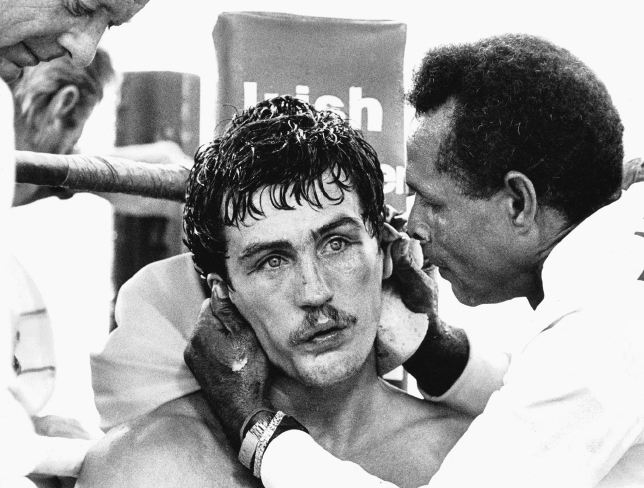

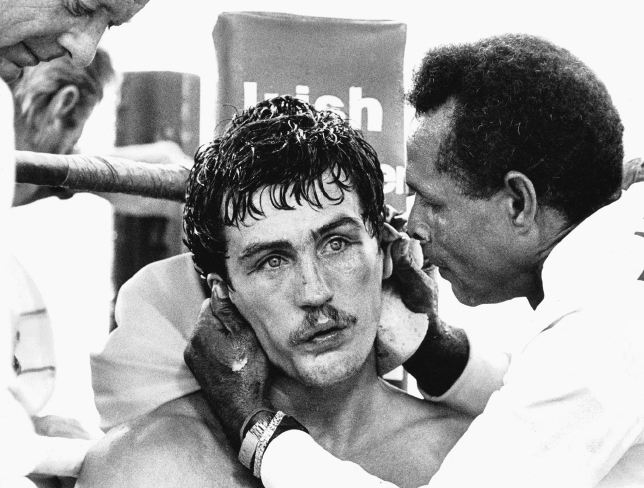

The extent to which photographs like these duplicate attitudes found in sculpture is often startling; in the case of a picture of boxer Barry McGuigan we actually have to draw on the art historical past to explain why it works on us so powerfully.

The photo was taken by Chris Smith just before the last round of McGuigan’s unsuccessful world featherweight title defense against Steve Cruz in Las Vegas in 1986. The effect of the photo is immediate and direct: there is pain turning into numbness, exhaustion—for any boxer physical exhaustion is always ontological exhaustion: he senses not just his energy but his being draining away—and a courage that, through years of training, is a matter of reflex. An active representative of our own compassion, the black trainer rubs the head of the white fighter (a reversal of the usual racial roles) as tenderly as a mother soothing her child. Perhaps he whispers encouragement, but at this distance from the everyday, words are meaningless.

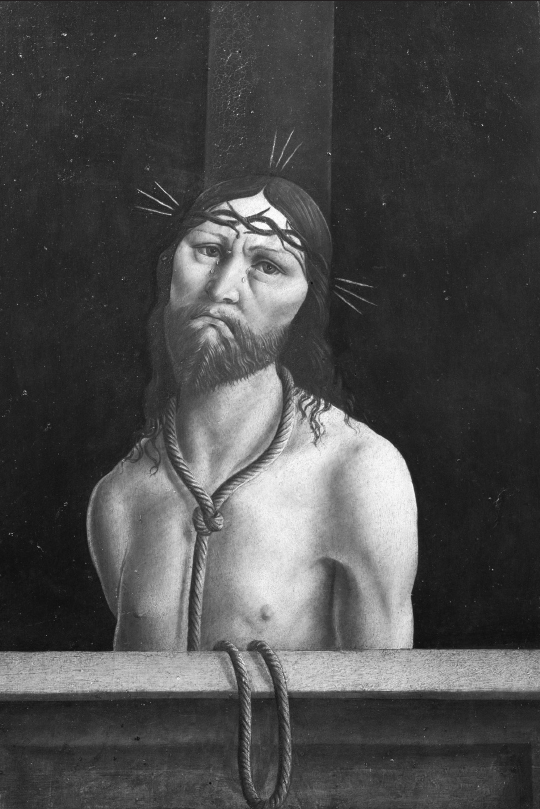

What makes the photograph so haunting, though, is the way that it conflates a number of common and closely related (so closely related they tend, in memory, like the statues in the Tuileries, to blur into each other) Renaissance representations of Christ. Most obviously, McGuigan’s glazed eyes are illuminated by the unfocused agony of the Passion (see, for example, Antonello da Messina’s Ecce Homo), with the corner post and top rope forming a cross just behind his head.

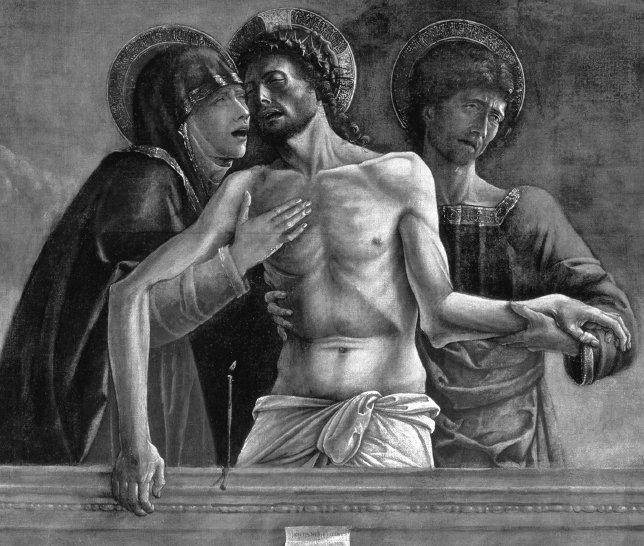

More generally, the arrangement of the figures in the photograph is uncannily reminiscent of any number of Pietàs or Depositions in which the dead Christ is taken down from the cross and mourned by the Virgin and others. Earlier I wrote that the trainer’s touch was as tender as any mother’s; in Smith’s photo and in paintings by Giotto and Bellini (whose Christ has the sinewy body of a featherweight) there is the same attempt to breathe life back into the battered body, to restore it to life. There is even a similarity between the simple accessories of the trainer—sponge, ointment, towel—and the traditional instruments of the Passion (nails, sponges, and so on).

Though Christ is dead when he is taken down from the cross, the Resurrection is often implicit in representations of the scene (in Bellini it is as if Christ is being helped to his feet). For McGuigan, the Resurrection of the last round—short-lived though it will be—is only seconds away, and in Smith’s photo he shares with images of the Resurrected Christ the devastating look of someone who has gone beyond the physical limits of the body.

Smith’s is not a great photograph because of these art historical parallels (like all great photographs, it has something startlingly felicitous—lucky—about it). However, for two thousand years the single most potent image in Western culture has been of a man, almost naked, in the extremes of exhaustion and pain—on the very brink of life and death—while others look on. With this in mind, it is not surprising that the photograph holds us. Moreover, boxing, with its naked suffering and triumphs, lends itself to a vocabulary at once relentlessly violent and strangely religious: the vocabulary of the Bible (the Old Testament primarily), of tragedy. After the devastating Ali-Frazier fight in Manila, one witness recalls finding Frazier lying in bed in semi-darkness:

Only his heavy breathing disturbed the quiet as an old friend walked to within two feet. “Who is it?” asked Joe Frazier, lifting himself to look around. “Who is it? I can’t see! Turn the lights on!” Another light was turned on, but Frazier still could not see. The scene cannot be forgotten; this good and gallant man lying there, embodying the remains of a will that had carried him so far—and now surely too far. His eyes were only slits, his face looked as if it had been painted by Goya. [My italics.]

Or by Holbein, specifically his Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, the painting that so disturbed Dostoyevsky: “In the picture the face is terribly smashed with blows, tumefied, covered with terrible, swollen, and bloodstained bruises, the eyes open and squinting.”

Years later, Frazier looked back and elaborated further: “I’m a hard man. I can look at you hard enough to make tears come out of your eyes. And I’m a proud man. I do whatever I got to do, whatever it is that’s got to be done. That’s the kind of man I am.… I hit [Ali] punches, those punches, they’d of knocked a building down. And he took ’em.”

Looking back on the first Madison Square Garden fight of 1971, Ferdie Pacheco, Ali’s doctor, observed: “He [Ali] was going to get up if he was dead. If Frazier had killed him, he’d have gotten up.”*

Earlier I wrote of how photographs of sport replicate gestures from the art of the past. This is fascinating but it provides the means to go further and see how sport, serving the same needs as the myths and religious traditions utilized by sculpture and painting, offers its own culture of parable, tragedy, and redemption—its own art; how sport affords the same potential for the expression of genius, passion, and vision that our culture often considers the preserve of opera, sculpture, painting.

There is a fair at the edge of the park. The air is full of screams from girls on the rides; the statues, meanwhile, maintain a stony silence. Summer is almost over. Many of the tourists have departed; tanned Parisians are returning from their holidays. I am reading on the grass. Nearby, some boys are annoying everyone by playing football. A miskick curls the ball toward one of the statues. Neck muscles tensed, the stone figure appears to be straining up to reach for the ball. There is a cheer as he heads clear and then play continues. I wish I had a camera to record that moment, to capture it.

1991

* All quotations about Ali and Frazier are from Thomas Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (1991).