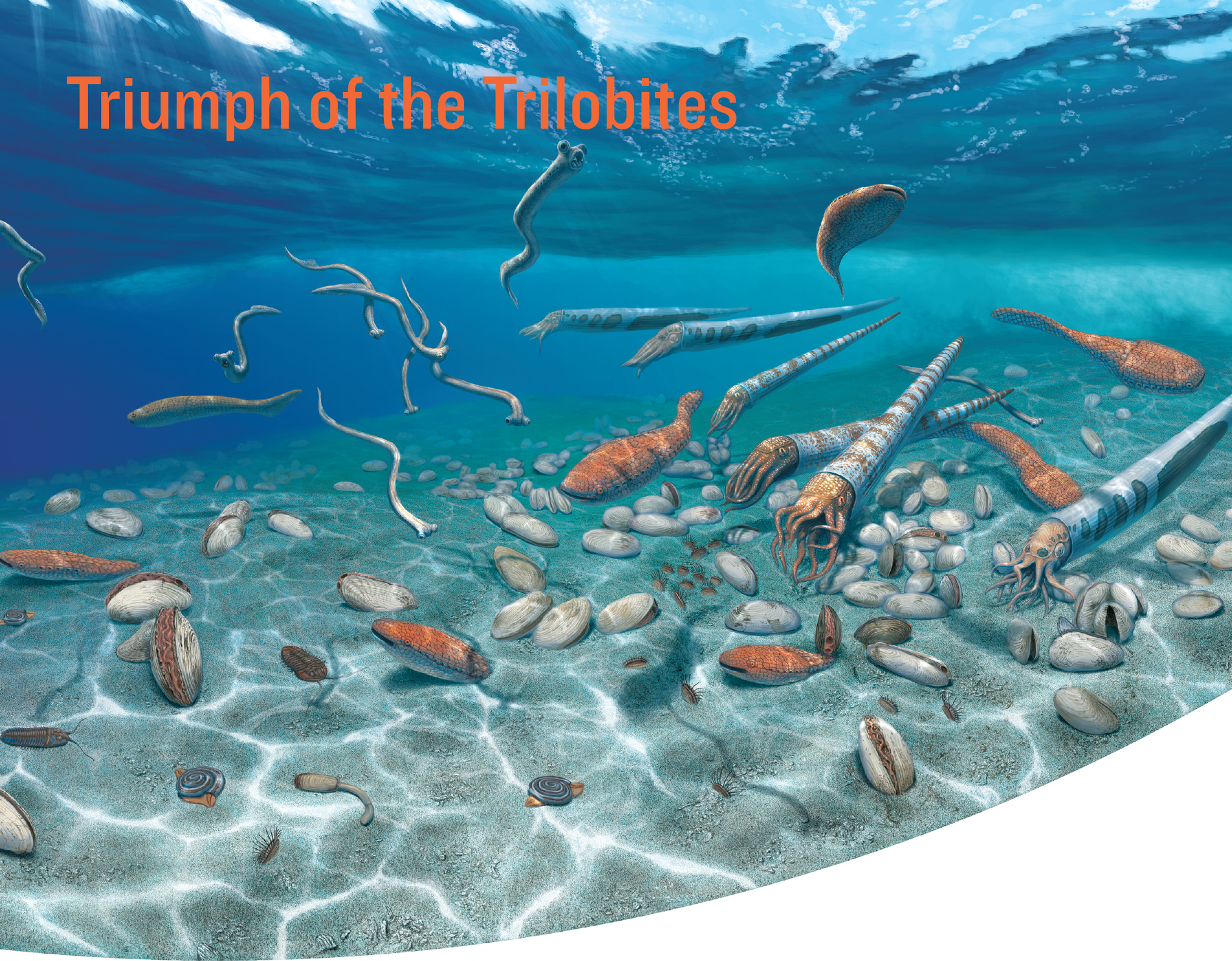

The next big burst of biodiversity occurred in the warm, shallow seas that covered continents during the Ordovician Period, when the number of marine species tripled within 25 million years. Life filled up space by swimming or burrowing into the seafloor. The planet’s first reefs formed from low-growing corals that provided habitats for bryozoans, crinoids, sponges, mollusks, and jawless fish. Among the earliest arthropods (a group that includes insects and spiders), trilobites thrived and peaked, developing an array of sizes, spines, and complex eyes. Trilobites’ time on Earth spanned about 300 million years and spawned more than 15,000 species. Earth’s first mass extinction, triggered by an ice age 448 million years ago, extinguished many marine species.

Also called sea lilies, crinoids like the Iocrinus subcrassus aren’t plants but relatives of sea stars. They capture plankton with feathery arms. They were the most abundant, diverse echinoderms of the Ordovician, but most kinds disappeared 252 million years ago.

The first fish had bony shields, like this Dartmuthia gemmifera, but no jaws. They sucked up particles from the seafloor. Today’s jawless lampreys and hagfish still represent their distant ancestors.

Rugose corals like Favistella alveolata helped form the first reefs, supporting thriving marine invertebrate communities.

During their history—twice as long as that of the dinosaurs—trilobites displayed diverse anatomy and behaviors. Bumastus decemsegmentus curled up like an armadillo for protection from predators.