In a vast ocean rife with reefs, Devonian Period fishes developed jaws for catching or crushing prey, such as squidlike ammonoids. On land, the first plants appeared, with short stems and lacking leaves, roots, flowers, and seeds. Early trees, like Archaeopteris, spread by spores and grew tall in moist places. The fishlike ancestors of tetrapods (“four-footed” backboned animals) evolved their legs and feet while still living in the water. These pioneers would give rise to all land-dwelling vertebrates. As microbes and plants provided food and created habitats, more animals started to come ashore—gradually adapting to a life with sun, air, and gravity.

Armored fish called placoderms, some with lethal, bladelike jaws, dominated Devonian seas. Bothriolepis canadensis was quite abundant, but it and all the placoderms mysteriously went extinct.

The first tree with a woody trunk, Archaeopteris minor sprouted roots that anchored it in the soil. Newly abundant plant life may have caused cooling that killed off many marine species.

Aquatic Acanthostega gunnari had six-digit hands and feet that it used to paddle or come ashore. One of the oldest tetrapods, Acanthostega is a key link in a sequence of fossils that shows the transition from fin to limb.

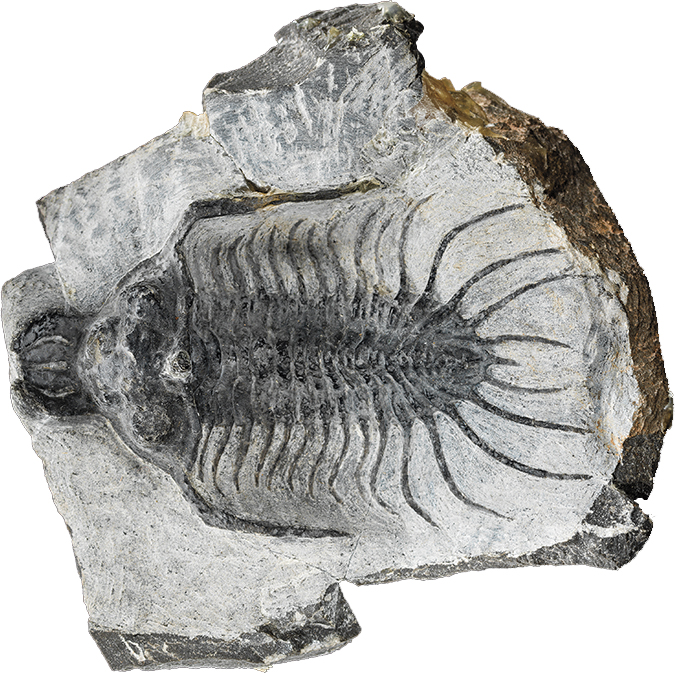

The trilobite Quadrops flexuosa may have used a rakelike projection on its head to sift through sediment for food.