UPON opening his eyes late one summer morning the author was very much startled and astonished at an apparition he beheld upon the wall. He saw at one side of the room, in a waving circle of light, a horrible, gaping monster that was about to make a mouthful of a wriggling, big-headed creature, as large as a cat. Upon turning over in bed and facing the window, the cause of this strange phenomenon was seen. The “gaping monster” proved to be a tiny gar, and the wriggler nothing more nor less than a tadpole. The curtains of the window had fallen down upon each side of a glass globe in which some aquarium pets were quarrelling. A ray of the morning sun had found its way into the darkened room through the fish globe, and by some unaccountable means transformed the globe into a sort of magic lantern lens and slide, throwing the magnified reflections of the inmates of the aquarium upon the wall. The gradual change in the position of the sun caused the vision to fade away in a few moments, and the writer has never since been able to arrange the light so as to reproduce the same effect. Fortunately, however, some one else has discovered the principle, and from it evolved a simple magic lantern, which any boy can make for himself; an account of this invention lately appeared in the Scientific American, and the editors of that paper have kindly consented to allow the description to be used for the benefit of the “American Boys.”

All that is required for this apparatus is an ordinary wooden packing-box, A (Fig. 212), a kerosene hand-lamp, B, with an Argand burner, a small fish globe, C, and a burning-glass or magnifying-glass (a common double or plano-convex lens), D. In one end of the box, A, cut a round hole, E, large enough to admit a portion of the globe, C, suspended within the box, A, with the lamp, B, close to it. The globe is filled with water, from which the air has been expelled by boiling.

Now moisten the surface of a piece of common window-glass with a strong solution of common table salt, dissolved in water, and place it vertically in a little stand made of wire, as shown at F, so that the light from the lamp, B, will be focused on it by the globe, which in this case answers as the condenser. The image of the glass will then be projected on the wall or screen of white cloth, G, providing the lens, D, is so placed in the path of the rays of light as to focus on the wall or screen. In a few minutes the salt solution on the surface of the glass, F, will begin to crystallize, and as each group of crystals takes beautiful forms, its image will be projected on the wall or screen, G, and will grow, as if by magic, into a beautiful forest of fern-like trees; it will continue to grow as long as there is any solution on the glass to crystallize. Then by adding a few drops of any transparent color to the water in the globe, the image on the screen will be illumined by shades of colored light. If the room in which the experiment is performed be very cold, frost crystals can be made by breathing on the glass, F. Many other experiments will suggest themselves, and when tried will be found both entertaining and instructive.

A Home-Made Kaleidoscope.

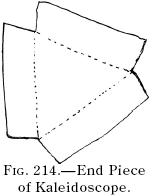

At all glaziers’ shops there are heaps of broken glass, composed of fragments of what were once long strips, cut with the diamond from pieces of window-pane, when fitting them for the sash. If you secure three of these strips of the same size, and tie them together in the form shown by Fig. 213, the strings will keep the glass in position. Cut a piece of semi-transparent writing-paper in the form shown by Fig. 214, so that it will fit on one end of the prism. With mucilage or paste fasten the overlapping edges to the glass; then with dark or opaque paper make another piece to fit upon the opposite end of the kaleidoscope; the opaque end-piece should have a round hole in its centre about the size of a silver twenty-cent piece—this is for the observer’s eye. All that now remains to be done is to cover the sides of the apparatus with the same paper used for the eye-piece, and the kaleidoscope is finished.

Drop a few bits of colored glass, beads or transparent pebbles in and turn the writing-paper end to the light; place your eye at the hole cut for that purpose in the opaque paper end, and as you look keep the prism slowly turning; the reflection in the glass will make the objects within take all manner of ever-changing, odd, and beautiful forms. A kaleidoscope made in the manner described is as serviceable and produces as good results as one for which you would have to pay several dollars at a store. One of the home-made ones can be manufactured in ten minutes if the pieces of glass be of the same length, and need no trimming to make them even.

The Fortune-Teller’s Box.

There exists in all countries a class of people who make their living out of the proceeds derived from tricks and deceptions practised upon the ignorant, credulous, or superstitious portion of the population.

In the by-streets of almost any large city may be seen signs posted up on dingy looking houses, which, if they were to be believed, would lead us to think that the gifted race that live in these dwellings can, by the aid of spirits, fairies, or by the signs in the heavens, give accurate information of all past or future events.

Some of these so-called mediums make such bungling attempts at magic and necromancy that it is a wonder that they are able to deceive any one. Others, however, perform some really wonderful tricks.

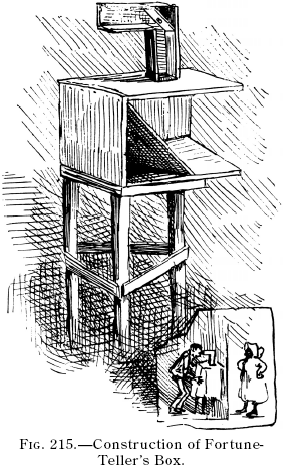

With a little trouble and no expense any boy may fit himself out as a fortune-teller, and have an unlimited amount of fun with his friends, who may be mystified and puzzled by simple contrivances, which, if explained to them, would be immediately understood. The professional fortune-teller will take persons into a dimly lighted room and ask if they wish to see their future wives or husbands, as the case may be; of course they do. The witch then leads them up to a table, which has an apparatus on top arranged so as to allow the dupes to peer in for a sight of their lover. When they really see what appear to be live, moving figures inside the tube, they go their ways rejoicing, fully convinced that there is truth in magic. One of these fortune-teller boxes can be made of any old wooden box. Such as is used for soap or candies is generally about the proper dimensions.

Knock one end of the box out, and cut a square hole in the lid in which to fit an inverted L-shaped apparatus. The L should be open at both ends, but tightly closed upon the four sides. A small mirror must be fitted in the L at the angle (see B, Fig. 215), and the L fitted in the square hole in the top of the wooden box in such a manner that any image cast upon the large looking-glass, A, in the wooden box, will be again reflected in the smaller mirror, B, at the angle in the L, and from thence to the observers eye when placed at the open end of the L. This can best be arranged by experiment. The open end of the wooden box must fit closely in a square hole cut in the partition or curtain that separates the young magician’s apartment from a room or closet occupied by an accomplice. Cover the box with a cloth which has a square hole in it, and fits snugly around the bottom of the L, covering and concealing the suspicious-looking, large box beneath. If the work has been neatly done, the machine will look like an ordinary table or stand with an innocent-looking peep-box on top of it.

Secure some friend for an accomplice, whom you know to possess a ready wit and a knack for “making himself up,” with the aid of burnt cork and a few old clothes, so as to take any comic character that the occasion may require, with only a few moments’ notice.

Supply him with what wardrobe he may require, burnt corks, flour, etc., and then fix up the programme between you, so that the boy behind the screen will know just what to do, from listening to what is going on in front, at the fortune-teller’s box.

When all is arranged, the fortune-teller may announce to what friends or visitors he may have, that, owing to the conjunction of certain planets, he is enabled to entertain them by showing to all who have any desire or curiosity to see such wonders, glimpses of the past and future, and to prove it, if any of the company would like to behold a life-like, moving image of a future wife or husband, he (the fortune-teller) can bring up the image in a magic telescope, which was obtained from a direct descendant of Aladdin. The young magician must, by preconcerted arrangement, bring a man or boy out for a first peep. At a private signal of a word or exclamation, the accomplice steps in front of the open end of the wooden box behind the partition, dressed as an old colored lady. The image is at once reflected upon the mirror at A, and from that to B, thence to the observer’s eye. After the latter has had a good look, the rest of the company may be asked to take a peep and see their fortunate (?) friend’s choice for a wife. When they see the old colored lady there will be a great laugh, in which the boy upon whom the joke has been played will join with all the greater zest, because he knows he will soon have a chance to laugh at some one else. The fortune-teller must guard with zealous care the secret of the box, and must discourage any too curious persons from handling or examining the apparatus. A little mystery is necessary to keep up the fun.

The Magic Cask.

After the fortune-teller has amused his friends sufficiently with his magic telescope, he may end the séance by inviting the company to another room and bidding them remain at the door while he examines something at the other end of the apartment—the something is covered with a cloth. Upon reaching the object, the magician must turn suddenly and face the guests in the doorway, and, in vehement language, accuse them of doubting the reality of the visions he has conjured up for them, stating that he overheard some among them say that it was nothing but a trick. Rather than be accused of such deception, he, the great wizard, prefers to perish! At this part the conjurer must quickly remove the cloth concealing the object in the corner, and disclose a barrel, marked in large letters, Gunpowder! Striking a match, the seemingly desperate wizard applies it to a fuse that hangs from the bung of the barrel, and, assuming a tragic attitude, awaits the result. The guests will be uncertain what to do, and, half in doubt whether to laugh or run, they will probably stand their ground, but anxiously watch the fuse as the light creeps up toward the bung of the terrible cask of gunpowder. When the fire reaches the barrel there is an instant of suspense; then some one in the secret lets an extensiontable leaf fall upon the floor in the hall or adjoining room, startling the guests and making a loud noise; instantly the staves of the barrel fly apart and fall upon all sides of the head, radiating out like the petals of a sunflower, from the centre of which the fortune-teller’s accomplice steps forth and greets the company.

How the Barrel is Made.

Any cask or barrel large enough to hold a boy in a crouching position will do to manufacture a magic barrel from. To make one of these trick-boxes requires no particular skill. It is necessary to remove one head for the top, and, after joining the parts of the other head firmly together by cleats nailed upon the inside (see Fig. 168.—Snow-ball Warfare), burn a hole with a red-hot poker through each stave near the bottom, then burn corresponding holes through the bottom head; make the staves fast to the bottom by tying them with pieces of heavy twine. Around the top of the staves of the barrel tie another piece of twine; remove all the hoops, and all that will hold the staves together will be the twine at the top (see Fig. 216); as soon as that is severed, the staves will fall asunder. Inside the barrel the accomplice crouches with open pen-knife in hand, and at the proper time he cuts the string by passing the blade of his knife between two staves. Left without support the barrel staves fall, exposing the gentleman within to the frightened spectators, who, when they discover that there really was no gun-powder in the cask, will welcome the new-comer most heartily.

In amateur theatricals the magic cask can be brought in very effectively with the aid of a red light and appropriate ceremony. The audience may be led to expect a most terrible explosion, and with bated breath watch the fuse as the light slowly creeps up nearer and nearer to the bung of the cask. When the time comes as much noise must be made as possible; then, as the staves fall on all sides and spread out like a sunflower, a red light suddenly thrown upon a boy dressed like a scarlet imp, makes a pretty as well as a mirth provoking transformation scene.

Before exhibiting it, the barrel should be tried to see that it works properly, and the boy in the barrel should rehearse his part, and not forget to have a sharp-bladed knife ready to cut the cord at the given signal, otherwise the whole scene will fall very flat.