CHAPTER 3

From Earthly Land to Holy Land

The previous chapter discussed the central place of territory in the identity of Jewish writers of the Second Temple period; this chapter introduces a different—and even contradictory—area: the religious movements that were not bound to territory.

Territory serves as the platform and framework for all narratives in the Hebrew scriptures. However, the Hebrew Bible also provides inspiration for a different kind of Jewish identity, one that has no connection to territory. In the scriptural narrative, the nation does not emerge in the land but arrives from beyond it, beginning with the first of the nation’s patriarchs.1 A small group—Jacob’s sons and their families—descends into Egypt and becomes a nation before it returns, transformed, to the land.2 The Torah, with its national master narrative and foundational legislation, is given in the desert, before the nation’s entry into the land. The narrative of the books of the Prophets is the threat of the Jewish people’s exile from the land and their return.3

Thus, the Hebrew biblical perspective according to which the Jews are linked to their land is neither autochthonous nor indigenous; rather, it facilitates the view of a Jewish existence without a presence in the land of Israel, at least until the return from exile. However, while the nation may exist for long and repeated periods in exile, the memory of the territorial inheritance and the hope of repossession sustain them when they are outside it. As we saw in the previous chapter, throughout the Second Temple period, biblical territorialism found its way, in various creative permutations, into the writings of Jews in the land of Israel.

Yet this period also witnessed groups within Jewish society for whom territorialism was less central, occasionally even marginal. These groups largely transformed the physical land of the Jewish people, the territory in which it was supposed to live, into a conceptual apparatus. They developed a new type of Jewish identity. Informed by the contemporary need to live in the land and the obligation that fidelity to the Jewish scriptures imparted to interpret its territorial dimension, they nonetheless translated this duty into an ideal. Such groups sought to minimize the role of the land in their identity, and we find them among the movements active in the land of Israel during the Second Temple period and after the destruction of the Temple.

This chapter examines these movements in the context of one another, in Jewish society in and beyond the land of Israel, with attention to related ideological formations in emergent Christianity. All of these movements considered the Jewish scriptures to be authoritative, yet they developed an ideological apparatus that freed their identities from dependence on the physical territory of the Jews’ native land. This process transformed the actual land, to varying degrees, into a concept.

This process was not sudden and immediate. Below, I introduce the spiritual image of the land as presented in 1 Enoch and in the writing of the Qumran sect, which elected to leave Jerusalem. The shift from the land as a whole to the “city” of Jerusalem by the Jewish Hellenistic author of 2 Maccabees, as well as Philo, aligns with the Hellenistic atmosphere of Alexandria’s Jewish community. Philo reflects the exchange of the land of Israel for the “city” and the shift to universalism from territorialism. The birth of the term and idea of the “Holy Land” was also prominent in the Jewish Hellenistic world.

The evolution of Christianity, first as part of Jewish society and later with a separation from it, was accompanied by dramatic shifts in the view of territory. While the evangelical narrative took place in the land of Israel, that of Paul featured his wandering outside of the land and a shift in focus, for which the heavenly Jerusalem became far more central than the terrestrial city. During the second and third centuries, the Church Fathers who followed Paul altered the place of the land to an abstract concept and appropriated the religious status of the terrestrial land. Constantine’s revolution in the fourth century related to holy sites; from then on, Christian holy places shaped the map. This rise in the status of the holy sites was not, however, accompanied by a focus on the land within the borders. Thus, Christianity’s map of holy sites replaced that of the land.

“THE BOOK OF WATCHERS”: EARTHLY GEOGRAPHY WITHIN CELESTIAL GEOGRAPHY

While Enoch is mentioned briefly in Genesis and is most noteworthy for being raised to heaven by God (Gn 5:24), he appears in Second Temple literature as an exemplary figure and the focus of an elaborate narrative.4 The scattered fragments from Qumran that deal with the tradition of Enoch reflect his central place in the world of the sect,5 demonstrating the community’s familiarity with components of the Book of Watchers.6 The stories about Enoch, his visions, and his journeys in the heavens and on earth form the narrative framework for all the works included in the book we know as 1 Enoch or the Ethiopic Book of Enoch.7 The first work in the extant corpus, which includes five texts added later, is called the Book of Watchers for the fallen angels that function in this capacity. Expanding upon a biblical story from Genesis 6, it details their arrival and their improper contact with humans (1 En. 6–11). While its date of composition remains unknown, the relevant manuscripts found at Qumran suggest that it was composed at about the end of the third century or beginning of the second century B.C.E. Thus, this text likely precedes the Qumran community’s abandonment of Jerusalem and its establishment as a separate sect in the second century B.C.E.8

Centering on Enoch, who precedes Abraham’s appearance in the Jewish scriptures and thus the historiographic shift from universal history to the arc of Israel’s emergence, the apocryphal work has a more universal than national focus.9Along with this broader ethnic perspective, it features a recognizable intersection with proto-scientific inquiry into the natural world and the cosmos, and thus with Mesopotamian beliefs and opinions. Pierre Grelot referred to certain descriptions in the Book of Watchers as “mythical geography.”10 However, the actual locations within the fantastical geography of the work are all drawn from the land of Israel and its environs. These “real places,” at least as they are known in modernity, include Mount Hermon and its surroundings, the Arava or Jordan River Valley, the Dead Sea, Jerusalem and its surroundings, Mount Sinai, and most likely the Red Sea.11

One way to understand Enoch’s relationship to territory and geography is through Kelley Coblentz Bautch’s adoption of Peter Gold White’s theory of the “provincial principle,” according to which the mental map rooted in one’s consciousness is principally informed by the area in which he or she lives. However, Coblentz Bautch, like George Nickelsburg, tends to identify Enoch’s native region as Mount Hermon, based on the prevalence of associated locations in the work. Following this logic, the author’s demonstrated familiarity with Jerusalem and its surroundings, with their proximity to the desert east of Jerusalem, might lead one to conclude that his native location was Judea.12 At any rate, whether the author was a northerner or a Judean, most of the locations Enoch visits or envisions are within the boundaries of the land of Israel.

As noted above, when and where Enochian literature was composed remains unclear, as are the social and political circles of the author. Nonetheless, in the passages characterized by Mesopotamian views concerning the earth and the cosmology of the stars and the heavens, the author weaves a map of the land of Israel and its surroundings into the celestial geography of the world of the highest angels. Thus, it appears that Enoch constitutes the first expression of the perception of the land as a part of heavenly concept rather than as a terrestrial space.

QUMRAN: “EXILIC CONSCIOUSNESS” IN THE JUDEAN DESERT

Between 1947 and 1956, remains of approximately nine hundred scrolls were found in eleven caves near the northwestern edge of the Dead Sea. These scrolls are usually divided into two groups: biblical and extrabiblical scrolls. The extrabiblical scrolls can be divided further into two groups. Some bear “sectarian” characteristics particular to the ethos of those who, because of the corruption in the Temple and the city, left Jerusalem for the desert. The others do not bear sectarian characteristics.13

As soon as the scrolls were discovered, a scholarly consensus began forming that the Essenes, living at the Qumran site or near it, composed the scrolls.14 This has remained the principal assumption in Qumran research. In recent decades, differences and variants have been identified between the main sectarian compositions—that of Community Rule (Serek ha-Yaḥad or 1QS) and versions of the Damascus Document, and about the character of the Essenes as described in Josephus, Philo, Pliny, and other sectarian scrolls.15 This has led to the suggestion that subgroups existed under the general umbrella of the Essenes.16 As I shall show, at least as regards the issue of territory, the corpus shows significant heterogeneity, suggesting that a range of movements was represented in the Qumran library.17

The scrolls that have come into our possession do not suggest any orderly sequence. Researchers are guided by the beliefs and opinions they bespeak in their attempts to reconstruct the community’s ideology, and by the dominant position among scholars that the sectarian scrolls represent the ideology of a single movement.18 The question of their relationship to territory is also tied to this effort. Some view these scrolls as the creation of a single group that abandoned Hasmonean Jerusalem due to disapproval of its moral climate; they emphasize the pervasive sense of exile found in the texts. This is particularly evident in the scroll known as the Damascus Document, which opens by detailing the sequence of events that led to the community’s foundation. Researchers refer to this scroll as the “Damascus Rule” because of references to Damascus at several points in the text. For instance, it identifies the sectarians as “penitents of Israel who depart from the land of Judah and dwell in the land of Damascus.”19 If “Damascus” is a name for Qumran in this scroll, or other places in which groups from the same sect lived,20 then the reference is drawn from the book of Amos: “And you shall carry off your ‘king’—Sikkuth and Kiyyun, the images you have made for yourselves of your astral deity as I drive you into exile beyond Damascus, said the Lord, whose name is ‘God of Hosts’” (Am 5:26–27). Though still located within the physical borders of the land, the community understood itself as living in exile.

According to the sectarian scrolls, its members left Jerusalem and chose to disconnect from the physical Temple due to its corruption—despite the fact that it remained accessible to them, not more than a day’s journey on foot from their new home in the desert, which was probably their central location. This move has been interpreted by scholars such as Daniel Schwartz as the sectarians’ way of dispensing with the need for a physical Temple in favor of an innovative approach that nullified the immediate need for national territory, especially if that need could only be satisfied through moral compromise.21 They therefore convert the Temple and Jerusalem into symbols of their apocalyptic yearnings.22 If this line of interpretation is correct, their abandonment of Jerusalem in favor of life in the desert can be understood as exile from the territory in which they ultimately wanted to live; moral degradation overrode the location’s material availability, a situation requiring eschatological redress. Thus, what may appear to us as a voluntary departure was necessitated by the intolerable moral conditions in Hasmonean Jerusalem. In this view, the community asserted the priority of moral and spiritual purity over a commitment to territory. The sect’s sense of exile, even if in a sense chosen, thus transformed the territorial dimension of their identity from an immediate requirement to an eschatological aspiration that might only be realized in a perfected postapocalyptic world.

This is true as regards the Temple. The neglect of the Temple and Jerusalem, however, does not necessarily mean neglect of the land. In the Qumran scrolls, “the land” is coextensive with “the Temple” and both are identified with the circumscribed space of the community’s settlement. David Flusser has demonstrated that the sect viewed itself as Civitas Dei—the “lot of God” or “community of holiness”—in essence, a substitute for the service in the Temple and sacrifices in Jerusalem.23 Thus, we see in their identification of the land and the idea of the Temple with their own space the beginning of the transformation of the land from an expansive physical region to an abstract concept dependent more on communal than geographic identity.24 Their place of residence supplants the Temple, enabling their location to become the new referent of the scriptural land of Israel; the physical expanse and borders of their historical national territory can now be read metaphorically as referring to themselves.

Despite the community’s redefinition of the Temple and the land as its own location in the desert, and thus potentially as a metaphor for the community itself, they still envisioned their abandonment of Jerusalem and disassociation from the Hasmonean state as “exile in the land.” Their biblical allegoresis is therefore less than thoroughgoing. The locations they chose included the northwestern edge of the Dead Sea, which lies in the very heart of the land of Judah and was an integral part of the land of Israel. Yet as they cut themselves off from Hasmonean Jerusalem and its Temple, they legitimized a principled separation from the Hasmonean state in favor of a sequestered existence on its geographical margins. Taking up residence still within the scriptural boundaries of historic Judea, they imagined themselves exiles in one sense and occupying the center of the nation in another, further sharpening the distinction between national space and cultural identity. Legitimizing their secession from the Hasmonean state on principle, they departed from Jerusalem and left the Temple behind.

HELLENISTIC-EGYPTIAN JEWISH LITERATURE: FROM THE “LAND” TO THE “CITY”

The Jewish works of Hellenistic Roman Egypt express a strong Jewish identity that, while anchored in a voluntary diaspora, remains conscious of the territorial component represented in the land of Israel. The compositions maintain religious loyalty to Jerusalem and the Temple, even without any link to proximate residence. The clearest representation of this approach in our possession is 2 Maccabees, written by a Hellenist Egyptian Jew sometime in the second century B.C.E.25 In contrast to 1 Maccabees—which was written in the land of Israel and emphasizes the “border of the land,” its geography, and its relation to various regions—2 Maccabees focuses principally on “the city,” with very little reference to the land.26

The centrality of “the city” in this work reveals a Hellenistic approach that sees the Greek polis as the foundation of identity. As such, 2 Maccabees relates to Jerusalem as a polis27 and elides the existence and expanse of the land of Israel. This conception of Jerusalem as a polis with a Temple strongly suggests the way in which Greeks viewed the city-state, an approach adopted by Philo 150 years later. In other words, the polis shaped the identity of Jews in Egypt, with Jerusalem functioning as the native city-state for diaspora Jews.

Another significant Egyptian work in which detailed descriptions of the city of Jerusalem and the regions of the land are found is the Letter of Aristeas. This work reveals the experience of the Jews of Alexandria in the second century B.C.E., in particular.28 It contains a flattering description of the Temple, Jerusalem, and its surroundings (Let. Aris. 83–111), as well as of the land and its rivers (112–18). This description includes mythographic features, like its description of the Temple as occupying a “towering mountain.” It bears distinct Hellenistic characteristics that distinguish it from a realistic description, as well—so much so that it raises the question of whether the author had ever visited the land himself. This description glorifies the Temple, Jerusalem, and the land in an attempt to represent the native land of the Jews as sublime. The key to understanding the character of the description of Jerusalem and the land is found in the argument of Sylvie Honigman, who shows it to be utopian according to the template of descriptions of Egypt and India in the Hellenistic literature. Thus, Jerusalem is described as an ideal polis, and the land of Judah and its surroundings are idealized as well, with an abundance of agriculture and a large population. With the depiction of an important river, the author compares the Jordan to the Nile. The author thus describes Jerusalem and Judah as resembling Alexandria and Egypt.29

Thus, both authors—of 2 Maccabees and of The Letter of Aristeas—relate to and describe Jerusalem and the land of Israel inspired by the template of Alexandria and Egypt, which they admired. In the process, the real land of Israel and Jerusalem become jumbled—it becomes a utopian vision, with added attributes of the Hellenistic polis and Hellenistic Egypt in which the authors lived.

The Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo, like the author of 2 Maccabees, was an Alexandrian of the first century C.E. (ca. 20 B.C.E.—50 C.E.).30 As typical diaspora Jews of the time, they never held the actual national territory of the land of Israel as central to their identity, but the city of Jerusalem played an important role in their worldviews. For Philo, the idea of Jerusalem was interwoven with Alexandria to create an identity featuring complex affiliations. In a sense, he managed this through Greek concepts, viewing Jerusalem as the mother city, the metropolis, and Alexandria as the father, the “patria.” This ideological arbitration parallels the Hellenistic perspective prevalent among the descendants from Greek city-states who had settled in various locations around the Mediterranean basin.31 These settlers saw their ancestral cities as their native ones—their metropoles—and the cities in which they lived as their homelands. Adopting this perspective enabled Philo to identify with the Alexandria in which he lived, his homeland, without abdicating his religious loyalty to Jerusalem, which functioned as his ancestral metropolis. These loyalties did not contradict but complemented or completed one another: Alexandria as his patris and Jerusalem as his metropolis.32

As his metropolis and as the focal point of ancient Judaism, the earthly Jerusalem was central to Philo. His connection to it was at once religious and related to the template understood by Greek emigrants, making it a destination for pilgrimage.33 The Greek emigrants saw their city of origin as a metropolis and the city to which they immigrated as the patria, or homeland; Philo presented Jerusalem as the metropolis and Alexandria as the homeland/patria. Much like the author of 2 Maccabees, Philo transferred his territorial focus from “land” to “city.”34 This shift was a natural one for someone living in Alexandria and educated in the tradition of the Greek polis. According to ancient Greek thought, the polis—and not the country—was the primary political and territorial unit, and thus the place with which the Greek citizen identified, making Philo’s primary identification with the city an expression of his Hellenism. The same can be said for the author of 2 Maccabees, who employed a narrative framework around the distress and rescue of “the city” rather than the land more generally.35

This Hellenistic focus on the city is also found in works composed after the destruction of the Temple, such as 2 Baruch,36 in which Jerusalem functions like a Greek polis as the primary territorial unit. “The city,” for Philo, was Alexandria, the place where he chose to live and with which he wholeheartedly identified—but “the city” was also Jerusalem, which functioned as a pilgrimage destination, something he considered personally and ethnically elevating.37 Yet Jerusalem itself38 is represented in all of Philo’s writings as having two strata, one earthly, accessible through pilgrimage, and one ideal, “not wrought of wood or stone” but to be sought “in a soul, in which there is no warring, whose sight is keen, which has set before it as its aim to live in contemplation and peace” (Somn. 2:250).

As for the land of Israel, Philo expresses his relationship to it, for instance, through the commandments of the Omer, the sheaf offering brought to the Temple during the wheat harvest. He represents this as the first fruits “both of the land which has been given for the nation to dwell in and of the whole earth, so that it serves that purpose both to the nation in particular and for the whole human race in general” (Spec. 2:162–63). As the priest is to the nation, Philo asserts, so is the Jewish nation to the sublime land, for it ministers as a priesthood to God. He thus employs the land as the source of a demonstration of the privileged relationship of Jews to the world, describing them as “the nation which has shewn so profound a sense of fellowship and goodwill to all men everywhere, by using its prayers and festivals and first-fruit offerings as a means of supplication for the human race in general” (Spec. 2:167).

While scripture associates the first fruits with the nation’s arrival in the land and its settlement there, in the place where it produces its fruit (Dt 26), Philo interprets this passage in a manner that transforms Jewish presence in the land from focused on its own particular identity to possessing a cosmopolitan mission. Accordingly, not only is Jerusalem a metropolis to the entire world, Israel in its land is a human emissary. The Omer and the two loaves of bread brought daily to the Temple acquire a dual function, being offerings that are both “brought to the altar as a first fruit both of the country which the nation has received for its own, and also of the whole land; so as to be an offering for the nation separately, and also a common one for the whole race of mankind” (Spec. 2:162). This contrasts with the way early rabbinic sages, following scripture, address the sanctity of the land in the Mishnah, according to which a Jew is obligated to bring the Omer, the first fruits, and the two loaves of bread as an individual religious obligation (m. Kelim 1:6). Philo’s perspective, both unknown to the sages and quite foreign to their biblically oriented approach, accords the first fruits a universalist dimension so that they are also brought “for their own land and for all lands” (Spec. 2:171). Even prior to the rabbinic sages, the uniqueness of the land in contrast to all others was expressed through the first fruits and Omer, yet for Philo they become an offering by Jews in their unique role acting on behalf of all humanity.39

Yet Philo’s ascription of a universal function to the land of Israel as the source of offerings brought on behalf of all humanity potentially eroded its status for Jews. While Jerusalem continued to function as a focal point for Jews throughout the world, its Temple was now conceived as serving the entire world,40 so that through the Temple the land and the specific commandments relating to it acquired a universal function that potentially superseded its national significance. Philo could not ignore those Torah commandments, the performance of which depended upon presence within the land’s boundaries. These included the first fruits and the biblical portion relating to them, which emphasizes arrival in the land and the blessing of its fruits. This was developed by the rabbinic sages into an understanding of the unique sanctity of the land itself. Yet Philo’s more universalistic perspective subordinated both the land and the nation to the service of the entire earth and its inhabitants, bending national function to transnational purpose. This perception, which saw the influence of the Jews as universal, blurred the lines between Jews and gentiles by introducing the Jews as an integral part of the world.

THE LAND OF ISRAEL AS “HOLY LAND”: THE BIRTH OF THE IDEA

The author of 2 Maccabees relates to the “Holy Land” in the opening of his book (1:7) and amplifies the significance of Jerusalem as the “Holy City,” but other works dating to the period after the destruction of the Second Temple go even further.41 In 2 Baruch,42 Jerusalem is depicted as a heavenly city (4:1–7); it is similarly depicted in 4 Ezra43 (8:27–54) and Pseudo-Philo (or Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum), an additional work dated to the end of the first century (LAB 19:10).44 The idea of the heavenly city serves to raise the spirits of the nation after the catastrophe it has just experienced. The image of the heavenly city, in contrast to the Temple and the “city of destruction,” persists. By invoking it, 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch strive to console and encourage a despondent nation after the destruction of its main city and religious center.

Tracing the development of nomenclature for the city and the land proves instructive vis-à-vis the ability of Jewish identity to adapt to life in the diaspora in the wake of the historic calamity. In 2 Baruch, the expression “Holy Land” appears occasionally, referring to the land of Israel (63:10; 84:8).45 The land is referred to as the “holy border” in 4 Ezra (13:48). Robert Wilkin has argued that the concept of the “Holy Land” is more prevalent in the works of Philo than any other Jewish author in antiquity.46 However, employment of the “Holy Land” in the works of Philo and other Jewish authors in Hellenistic Egypt—such as 2 Maccabees, the Sibylline Oracles47 (3:266), and the Wisdom of Solomon (12:3)—affirms the enduring place of the land in their consciousness. Yet the concept of holiness is charged with a sense of isolation,48 so that it shifts the idea of the land from a natural place in the life of the nation to a place that belongs to another dimension. The popularity of the concept of the “Holy Land” demonstrates the diminished status of physical territory.49 This terminology, which is not found in rabbinic literature,50 characterizes the physical territory of the land of Israel as inherently sacred, transmuting it into something else, which is not tangible territory.

This sanctification into transcendence evokes the way in which contemporary groups of ultra-Orthodox Jews employ the idea of the “holy tongue.” They view Hebrew as the language of prayer and study, a tongue reserved for ritual purposes, while they speak Yiddish or English in their daily lives. Hebrew for them is not a practical language—just as the “Holy Land” is sanctified, but is not the land upon which they live. Rather, it is a transcendent, sanctified idea—at least until the End of Days, when the entire people of Israel will live there in peace.51

THE “PARTING OF WAYS”: CHRISTIANITY AND THE LAND

Near the end of the Second Temple period, Christianity began to develop in parallel with other religious movements.52 Its approach to the land was shaped in the second and third centuries primarily by Justin Martyr and Origen, and later in the third and fourth centuries by Eusebius of Caesarea and Jerome. These thinkers constructed a religious identity detached from any particular territory; it favored Christian universalism, significantly undermining the religious status of the physical land. Christianity’s separation from Judaism over the course of the first centuries of the Common Era occurred in tandem with its dissolution of territorial orientation. These entwined processes find expression in Christian scriptures, especially in the Synoptic Gospels,53 where the land of Israel serves as the stage upon which the story of Jesus’s life plays out. The area of interest includes Nazareth and its environs, the Sea of Galilee, the Mount of Olives and Jerusalem, the Judean desert, the Jordan River Valley, and part of Transjordan.54 Bethlehem, the Mount of Olives, and Jerusalem are “locations of remembrance”55 that tie Jesus’s activities to locations associated in the Hebrew Bible with King David; their mentions demonstrate that Jesus is the heir of David. When Jesus goes to Tyre and Sidon, and when his family takes him to Egypt, he exits the land to go abroad, sharply defining the central venue of his narrative.56 Accordingly, the land of Israel—and, in effect, only the land of Israel—functions in the synoptic literature as an integral part of Jesus’s figure and identity.

Paul, a member of the Jewish diaspora in Asia Minor before the destruction of the Temple, disseminated the message of Jesus around the Mediterranean Basin. It was Paul who dissolved the necessary affiliation to the borders of the physical land, paving the way for non-Jews, whether from Judah or abroad, to join Jesus’s movement (Gal 3:7, 28–29). After Paul, one was not required to have a genealogical relationship or to take on the historical religious practices and obligations in order to become a member of the ethnic community. As the land no longer held special significance, abrogation of the commandments relating to it and the cancellation of the requirement of ethnic descent went hand in hand with the erosion of its status.

This process of breaking territorial along with ethnic boundaries is expressed in the literary structure of the eighth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles. This is not a Pauline text; rather, Paul is depicted by the author of Luke. The focus is on the disciples’ activities in Jerusalem. Thereafter the action moves to Caesarea, Samaria, and Gaza, all of which are more liminal regions. With the inclusion of the centurion Cornelius in chapter 10, ethnic borders are ruptured, for the “holy spirit” now inspires gentiles as well as Jews. Paul appears in chapter 7, and the plot moves beyond the geographical borders of the land altogether. Thus, together with the opening of the ethnic structure of the people of Israel, the story breaches the boundaries of the land, inaugurating a transition from the Kingdom of Israel to the Kingdom of God.57

The Pauline approach differs from that of the Synoptic Gospels in that Paul explicitly censures the Sinaitic Covenant and its commandments glorifying the celestial Jerusalem in contrast to its earthly counterpart. In the Epistle to the Galatians (4:21–31),58 the “Jerusalem that is above” is cast in relation to Isaac, the son of free woman Sarah, as opposed to the derisive association of the earthly Jerusalem with Ishmael—called “the son of the slave woman” Hagar—who was cast into the desert. The desert is the place of the Sinaitic Covenant, established there with the commandments, which shackles the believer. The Epistle to the Hebrews casts it as a “foreign land” in contrast to the promised land of Jewish scriptures, which is now in heaven. These verses present the patriarchal narrative about the lives of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as a model for anagogical ascent. For all three indeed reach and live in the promised land (Heb 11:9), but as foreigners and exiles (11:13) in a “foreign land” (11:9). In fact, the text relates, “they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one” (11:16), which awaited them as God “has prepared a city for them” (ibid.). Abraham is now depicted as seeking heaven, “looking forward to the city with foundations, whose architect and builder is God” (11:10). In its final chapter, Hebrews annuls the status and location of the existing physical city and aspires to a future city: “we seek one [city] to come” (13:14).

Yet the spatial displacement of Jerusalem to heaven and its temporal removal to the eschaton proves only temporary. The Christian scriptural canon closes with a vision of how the celestial New Jerusalem will ultimately be established on earth as “the Holy City Jerusalem that descends from Heaven” (Rv 21:2, 10). Even in this vision, the city is still located in a land. It may be that this city is the same one Justin Martyr claims will be the location of the bodily resurrection in his Dialogue with Trypho, the “Jerusalem, which will then be built, adorned, and enlarged” (CXXX). At every point in this dialogue, the different aspects of Jerusalem are shown in contrast—the “promised land” that Abraham traveled to and in which the patriarchs lived as foreigners, the city that God prepared for them as its divine architect and builder. In other words, the land is replaced by the city, and the earthly city begins to become or be replaced by the celestial one.

While the process by which the physical land’s sublimity is downgraded through the abrogation of territorialism begins in the Pauline epistles, it is important to note that for Paul, the terrestrial city maintains a role as the subordinate of the superlatively important celestial city. This process reaches its peak when Origen, in early third-century Caesarea, engages the prophetic vision of a spiritual “heavenly city,” as well as a “heavenly land.”59 The author of the Epistle to the Hebrews had already disavowed aspirations to rule over a swath of earthly territory and a country with borders (9:11, 24; 13:14), obscuring the obligation to perform directives related to the land or commandments in sancta like the Temple. Thus, even when the long-awaited city descends from heaven, the land will have no significance. In his aforementioned Dialogue with Trypho, a second-century text, Justin Martyr employs the term “Holy Land” for the first time in Christian literature, in reference to an eschatological land, to combat Joshua’s division of the land with a future apportioning by Jesus. Accordingly, the process that transformed the land in early Christian consciousness from a physical location to a spiritual one, thus disavowing territorialism, took place over approximately 150 years.60

Origen’s spiritual disciple Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 260–339 c.e.), is an outstanding representative of the Pauline movement, for which the idea of holy places is foreign. Peter Walker helpfully describes the personal difficulty that Eusebius faced on this issue. Though leader of a movement that largely disavowed sacred geography, as bishop of Caesarea he was forced to participate actively in the establishment of Christian religious ritual. For instance, he was required to deliver a dedication speech for the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the pinnacle of Emperor Constantine’s project to mark locations considered holy with the founding of churches.61 As author of the Onomasticon, the Pauline Eusebius paradoxically became the first to formalize the relation of Christianity to the physical geography of the land, the territory in which the Christian past is rooted.62 However, the general perspective of the Onomasticon demonstrates disregard for the borders of the land. As the land lacks borders, it is not a distinct region, and the Christian presence has no impact on it as a whole. Therefore, the work is, in effect, a reference book for students of the holy scriptures solely interested in the specific locations of biblical geography.63

The fourth and fifth centuries were characterized by a continuation of Constantine’s campaign in the “discovery” of holy places—after the Council of Nicaea—which began to function as pilgrimage sites.64 The dramatic revolution begun by Constantine early in the fourth century, and its attendant “discoveries” of holy places, was supplemented by liturgy, the reading of specific verses and hymns on specific dates, in the second half of the fourth century. Thus were time and space further combined with text.65 But this process did not restore the status of the land as a territorial unity in Christian political or religious consciousness;66 it was only seen as a sort of aggregation of holy places.

This is also evident in the writings of the Church Father Jerome (342–420 C.E.). In his “Epistle 108,” written in 404 C.E., Jerome describes Paula’s pilgrimage to holy places in minute detail.67 And yet, in “Epistle 129,” he struggles with the idea of the “promised land.”68 Jerome contrasts the “Kingdom of Heaven” to the physical land, which is degraded. In the latter epistle, he creates a clear distinction between the description of the borders in Numbers 34 and those that were promised.69 In this way, he differentiates the land and its boundaries, which he views negatively, from the holy places he deems worthy of visitation and prayer; these, in his opinion, will be spiritually elevating and meritorious.70

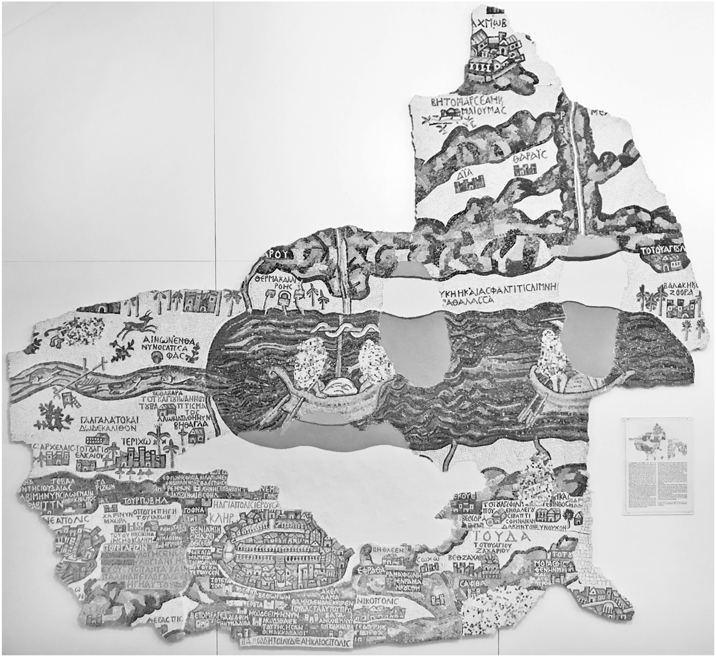

Though one might assume intuitively otherwise, in actuality pilgrimage to holy places does not of necessity entail territorial affinity with the land where they are found. As we have seen, the land of Israel was for Christians no more than the general region containing a collection of localized sacred locations. This view is diametrically opposed to the approach widespread among the rabbinic sages, for whom the entire land was inherently sacred. Aaron Demsky identifies an instructive divergence between depictions of the land in two different mosaics.71 The floor of a synagogue in Rehov, approximately five kilometers south of Scythopolis (Beit Shean), is decorated with a verbal and halakhic description of the land.72 Demsky compares this with a map mosaic from Madaba, which was incorporated into a church in the sixth century. Where the halakhic description focuses on the external borders of the land, the Christian cartographic depiction highlights the variety of “holy sites,” without representing the borders of the land at all.

However, Glen Bowersock’s analysis characterizes the Madaba Map as emphasizing the significance of the region’s cities in their space and their urban structure; he does not view it as biblical in nature.73 Moreover, the mosaic may not necessarily be dedicated to the Holy Land; its missing elements may well go far beyond the land and depict cities in Asia Minor. The map does, nonetheless, include Christian theological features, reflected in its emphasis on the churches in Jerusalem and depiction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher at the center of the city. The divergence between the Madaba Map and the Rehov inscription is instructive. The latter is dedicated to halakhic borders; the former focuses on cities rather than borders and is grounded in a Christian approach to sites and traditions. The disparity between them illuminates the conceptual disparity between the sages and Christianity.

FIGURE 2. Reconstruction of the Madaba Map. Akademisches Kunstmuseum-Antikensammlung der Universität Bonn. Photograph by Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah.

The difference identified between these mosaics presents an opportunity for further analytical comparison. As introduced above, Eusebius’s Onomasticon stands at the forefront of Christian articulation of its relationship to space. In addition to the features already discussed, this fourth-century work written in Caesarea contains a hierarchical list of places mentioned in the Jewish scriptures and the New Testament, describing each individually in relation to these sources. This approach is reflected in the Madaba Map. But no parallel is found in rabbinic literature. The focus of the textual mosaic from the Rehov synagogue, describing the borders of the land and the status of peripheral areas, involves an important rabbinic legal principle. Halakhah maintains fidelity to the biblical distinction between the land of Israel and the places outside of it. Some commandments apply specifically and uniquely inside the borders of the land. The principle governing rabbinic engagement with geography is therefore neither academic nor exegetical, as in the Onomasticon. Rather, it serves to indicate borders for legal purposes, to designate where commandments specific to the land of Israel must be observed and where they must not.

THE SHIFT FROM EARTHLY LAND TO HOLY LAND

The development of religious groups for which territory took a marginal role is not necessarily linear. In this chapter, we followed the trends that diminished the place of territory in their lives, Jewish religious communities in the land of Israel, and the diaspora in the Second Temple period. From there we journeyed to the Christian writing of the first century C.E., beginning with the Pauline movement and ending with the revolution of Constantine regarding holy sites.

The discussion of these communities moved chronologically with the literature, beginning with Enoch, the oldest composition, which interweaves an Israelite geography of a mythic geographic style and space. The Qumran scrolls reflect an approach that viewed the congregation or community as Godly, a replacement for territory and Temple. The Qumran community—which perceived the world through a division between “light” and “darkness”—neutralized and replaced the distinction between the land and the world outside of it, a central organizing dichotomy found elsewhere. As such, the War Scroll states that the world’s great victory will be accomplished in the rooting out of evil, not the recovery and resettlement of the land. But this idealization proves neither absolute nor final; neither explicit cancellation nor affirmation of the territorial dimension can be found. The territorial dimension is not effaced, but transformed and demoted into a secondary—yet still critical—concern, a necessary means to a greater end.

Jewish literature from the end of the Second Temple period comes to us primarily from Hellenistic Alexandria. The Alexandrian works discussed above, 2 Maccabees and the writings of Philo, display a common attitude to territory. Living by choice in Alexandria, their authors make the orientation to the land of Israel secondary to loyal affiliation with Jerusalem according to the template of the Greek polis.

Yet immediately following the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple in 70 C.E.—indeed, as its ruins were still smoldering—writers in the land of Israel composed 2 Baruch and 4 Ezra. These works were intended to reassure Jews who had absorbed the great blow of the destruction of their principal city and its Temple. The concept of a celestial Jerusalem, which was imagined as above and thus beyond harm, became their primary concern. Along with the Alexandrian works and others of the same period, including Pseudo-Philo, they inaugurated the term “Holy Land.” This nomenclature demonstrates the process by which the physical land was transformed into a religious concept and occasionally excluded from the temporal world and the mortal sphere altogether.

The process of Christianity’s separation from Judaism was multifaceted; moreover, it occurred in different places. One of its characteristics was the erasure of the role of the physical land in Christian literature. Even Constantine’s revolution, which established the map of holy places of pilgrimage, did not ascribe importance to the land in which they were all to be found, neglecting entirely to define its borders and obscuring its identity as a unified and continuous expanse. This would become a major distinction between the approaches of the sages and the early Christians.

In contrast to the territorialist movements in Jewish compositions in the Second Temple period, examined in the second chapter, these groups minimized the territorial dimension in their Jewish or Christian identity. In the coming chapters we will study the place of territory in the world of the sages—first looking at the way in which the sages in the land of Israel and the Babylonian exile perceived the land in the early centuries of the Common Era and then examining the place of holy sites in the world of the sages.