Chapter 31

Hāmweard, ðu londadl hǽðstapa, in 22 days

Homeward, you landsick heath-wanderer, in 22 days

After four days, Conradi calls me over to the first precinct for an interview. I wait, but he is nowhere to be found. Maybe the officer sitting at the high desk legitimately doesn’t know where he is. Maybe this is some new kind of human game that I have not yet learned. Officer Buton simply nods me toward the row of upholstered chairs decorated with dark ellipses of old gum.

If there is anywhere in the world where humanity in all its excess and misery and general meatiness is more pungently represented, I don’t ever want to go there.

I sit next to a thin, bruised woman who smells like pepperoni and methamphetamine and fear. Another person of interest who is of interest to no one.

Half an hour later, I tell Officer Buton that I can’t wait anymore.

“Don’t leave town,” he says without looking up from his newspaper.

A few days later, I am called in for a repeat performance. This time, Conradi manages to show up. He sits across from me at a narrow table covered with faux-wood contact paper meant to cover up the chips and gouges in the previous surface. He has a map and a complex calculation that allowed him to reconcile my E-ZPass record with Janine’s murder.

“Why wouldn’t I have just driven up the Taconic? No tolls, no records. Leaves me on the east side of the Hudson?”

“And without an alibi.”

I push down a bubble under the contact paper with my thumb. It springs back up. Nothing I say is going to do anything to change his mind. He continues to focus on questions he has already asked. I continue to give him the answers I have already delivered.

Another detective I recognize as Hernandez sticks his head in the room. “Sam?” he says.

Samuel Conradi, I repeat to myself while peeling off the excess contact paper sticking over the edge of the table.

“Don’t do that,” Conradi says irritably.

The other detective looks briefly at me. “He’s leaving now,” he says. “I told him not to go anywhere.”

Popular refrain. I look at my watch. I’ve wasted two hours here already.

The other detective starts to close the door, but as he does, I am hit by the unmistakable stench of lavender breeze and the off-gassing of polypropylene carpets. I leap up, my chair flying behind me, and run to the door, loping after the scent, following it toward the door. Conradi yells behind me.

Tiberius is a Shifter-Pack mix. Larger than Pack and much larger than the typical Shifter, but any Shifter—because that’s who it must be—will still be larger than a human.

There’s no one here but two uniforms and a handful of humans. Two women talking to each other and a white-haired man in a neat suit halfway out the door, fishing for something in his pocket.

“Did you see a big man?” I yell at the policemen. They look at me skeptically. “I’m looking for a big man.”

“Me too, honey,” one of the women says. “Me too.”

Her friend and the two uniforms start to laugh.

Disgusted, I turn back toward the interview room. Conradi watches me from his perch against the doorjamb, his arms crossed in front of his chest. “Sorensson? How well do you know Daniel Leary?”

“Who?”

“Leary. Daniel Leary.”

“Never heard of him. What is he? An Irish poet?”

Conradi looks at me, trying to decide something.

“Don’t leave town,” he says.

• • •

Hāmweard, ðu londadl hǽðstapa, in 12 days

Homeward, you landsick heath-wanderer, in 12 days

I’ve been sleeping badly again, and the dream comes back to me almost as soon as I fall asleep. This time, I am in the interview room when the change hits. This time, instead of my legs changing, only my head does, but Conradi doesn’t seem to notice. He keeps yelling at me to tell him what I did with Janine. I feel my mouth’s high, narrow roof and its frilled black lips and sharp teeth. I try to respond, try to tell him that I am not the monster, that when I kill, I eat.

But all that comes is a howl.

The buzz of Thea’s text wakes me up, my heart pounding. I press on my chest with the heel of my hand. My fingers shake as I dial her number back, but the moment I hear her, my wild reaches his head up for the soothing stroke of her voice.

I make up excuses to keep her talking. I miss her so much. I miss her body and her voice and the times between when she isn’t speaking. I tell her I’m not sleeping well and that I need to listen to her. Just please tell me about what’s happening in the forest around her. How it’s waking up to spring.

Thea puts her phone on her little unfinished pine table with the charger so that I can hear her.

With my wolfish senses, I listen as she makes her dinner and washes her dishes. She tells me about the first wail of the loon and the gruk-gruk of the mergansers and the almost living sound of ice as it twangs and cracks. She’s seen newts, she says, sunning in black water, and ground bees and partridgeberry and liverwort and speedwell. A clutch of eggs. The promise of peepers.

She says she misses me too. Then against the soft crumple of pages turning, I fall well and truly asleep and do not dream.

• • •

Hāmweard, ðu londadl hǽðstapa, in 7 days

Homeward, you landsick heath-wanderer, in 7 days

“The mail’s in, Mr. Sorensson,” says Gregori, the doorman.

I’ve become one of those people. The people for whom the arrival of mail gives rhythm to otherwise rhythmless days. Because my bills are all paid electronically, I used to gather it once a week and run it through the shredder in the mail room. For the first time, I look at the offers for credit cards and the Dear Valued Customer notices.

One postcard sports a photograph of a peaceful glade with overhanging willows.

Dear Neighbor, it says in ostentatious lettering. Have you thought about where your final resting place will be?

I feed it into the shredder, because I know where my final resting place will be. I’ve always known. My final resting place will be in the descending colon of a coyote.

“Elijah?”

Oh shit. Mutton.

And sure enough, Alana stands at the mailboxes in that raw wool poncho. But it no longer has any power over me. Except for the salivating; that simply can’t be helped.

“Hello, Alana.”

“What are you doing home at this hour? Did you lose your job?”

“Nope, just taking some time off.”

“Is this about the…you know? Transience?”

Oh god.

“No, just some time off. Actually, though, I’ve got an appointment coming up—”

“Did you know there’s a rat in the laundry room?”

“What were you doing in the laundry room?”

“Inez found a lump and took the day off? I saw it? It ran right between the dryers?”

“Have you thought about taking Tarzan downstairs and letting him have a crack at it?”

She cocks her hip and rolls her eyes like a juvenile. “Don’t be ridiculous. Tarzan’s not meant for that kind of thing.”

I don’t ask what the hell Tarzan’s actually meant for. Nor do I ask what exactly makes her think that I was “meant for that kind of thing.” I know. She is still angry with the super over his inability to fix her remote control. Now Luca is unavailable, and because I was stupid enough to sleep with her, I have to play backup husband.

But my downtrodden wild, now woken by mutton, stretches out his front paws, his tongue lolling out the side of his mouth. Whining.

“I’ll take care of it.”

Thankfully, she doesn’t ask how I, Elijah Sorensson (JD, LLM), propose to get rid of the rat.

At 3:00 a.m. when the building is asleep, I pull on my bathrobe and white slippers bearing the name of a hotel I don’t remember visiting and head down to the laundry room with a big bag of sheets I don’t need to wash but to explain why I’m skulking around in the basement. The laundry room is bright with a warm, tiled floor and a big farm sink. Looking between the dryers, I find the hot-water pipe leading down to the subbasement.

Careful to avoid the cameras, I dart down the stairs into the subbasement, to the big, dark room where the boiler and elevator, HVAC and other mechanicals that support the stage set of the building live. In the middle is a forest of struts from a planned storage area that was abandoned when the subbasement flooded during Hurricane Irene and again during Hurricane Sandy. To the side are mountains of ductwork covered in blue plastic.

The concrete is cold and damp on my now-naked body, but I don’t care. I stretch out my arms, the heel of my palm straight and long. My skin starts to tingle and my hands narrow and lengthen and bones become rubbery and bend where the muscle tightens. My nose itches. The boiler growls menacingly and is the last thing I hear as my ears and eyes migrate into their wild form.

When I come out, I bound, tossing myself into the air and down again. I bound without incident along the full length of the subbasement, over rolls of baffling and piles of screens and the low drainage gutters, until one hind foot catches on a pile of tiles left over from some renovation project and they fall over.

I listen to make sure no one heard. Then, with my shoulders low and my nose to the floor, I race among the giant trunks of steel oozing their oily sap into the ground until I light upon the dusty, musky fragrance of rat.

Over the creaking and knocking of steam heat and the burbling of the pump comes a slight scritching from somewhere behind a stack of plasterboard propped against one wall. Because the wall got wet and then dried out again, it doesn’t take much for me to claw out a hole big enough for my muzzle. I sniff once again to make sure I’m right, and then I wait, legs tense, chest leaning forward.

Half an hour later, the rat risks creeping out.

He is delicious.

When my change is done, I pick up my dirty clothes bag. The super’s wife watches me leave the laundry room through a crack in her door.

In the bathroom as I wait for the hot water, the mirror fogs up. I rub my fingers through my hair gray with plaster dust and lick the dried blood dribbling down my chin.

• • •

“The mail’s here, Mr. Sorensson. And I believe you have a package,” says Gregori, handing me the thing I’ve been waiting for: a large box from Great North LLC, Plattsburgh.

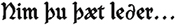

As soon as I get back to the apartment, I slice open the tape with my seax, releasing the scent of deer hide and black walnut. There’s an envelope inside with the instructions that Gran Jean promised to send. What she sent was a photocopy of the original Old Tongue instructions written out in tiny, archaic script.

It takes fifteen minutes of migraine-inducing squinting just to get through Nim þu þæt le∂er… “Take you that leather…” I doubt anyone has actually used these instructions. Gran Jean learned how to make our braids at the knee of Gran Wulfwyn, who learned at the knee of Gran Sæþryþ, who learned at the knee of Gran Dagmar, who probably learned at the knee of whatever Mercian sadist originally wrote this.

“Take you that leather.”

Screw it. Leaning over the counter, I rub my finger along the trackpad until I line up the half-dozen YouTube videos I need to take the place of that ancient wolf. It takes me a couple of hours to make a smooth lacing. The deer hide is soft in spots, and I have trouble keeping the pressure consistent, so it is not a single thong, but in the end, I have six lengths. I make three slightly longer.

Just in case my seax was dulled by opening the box, I give it a few more passes on the whetstone before rinsing it, drying it, and slicing it along the length of my sternum. As the blood beads, I lay the first leather thong into the gash, holding it tight with the flat of one hand and dragging it through with the other. It is painful, but the constant abrasion keeps the wound from healing before I can finish with all six. I don’t know if blood stains marble, but because of our fund manager’s admonitions about resale value, I am careful to lay them out on a piece of plastic from the dry cleaner.

In a proper Bredung, the long, single thong would be stained with the blood of the Alpha before being tied around the couple, who would then mount until the leather was stained once more, this time with the results of their coupling. It is all very symbolic: the hide and the oak tannins represent our land; the blood, our pack; the seed, our mates.

Instead, in the shower stall, I close my eyes and imagine that proper Bredung, in which Thea’s naked body is tied to mine. Under the spruces, where the needles make a soft, fragrant bedding. She rides me hard until her ironwood eyes soften and cloud, and her body clenches around me. A feral howl reverberates through the luxury condominium, and someone bangs against the shared wall. Panting and shaking with one forearm propped against the marble panel, I come to my senses long enough to anoint the six strands.

Why is this so important for me to get right? It’s not because Pack will ever acknowledge it. Not because Thea will even know what it means. I want to get it right because this woman who knit back my unraveling heart and body and wild is my mate. Doesn’t matter if I’m the only one who ever knows it. She is.

I spend the night braiding and unbraiding until I am content with the shape and size and smoothness. Each has a loop made of a braid of three, then the two loose ends are braided into a six-strand braid. The larger one I leave on the Tiffany tray (To Elijah Sorensson with Gratitude from Americans for Progressive Packaging). The smaller one, the one I braided and rebraided until it was as perfect as I could make it, I coil into the padded overnight envelope with a casual note. Had some time on my hands, so I made this, I write as though it was an afterthought. Hope you like it.

Two nights later, she sends me a picture of the perfect gold column of her neck, with my braid. It’s a little twisted from its day spent coiled in transit, but it will relax soon against the warmth of her skin. Then it will lie flat around the base of my mate’s throat.

In my icy, sterile bathroom, I fumble, threading the knot at one end of my own braid through the loop at the other. I slide it around so the fastening is at the back, hidden under my hair. As I put my hands on either side of the marble sink, I flex my shoulders. There are wolves in the Great North who will challenge my right to wear the braid.

But they will do it only once.