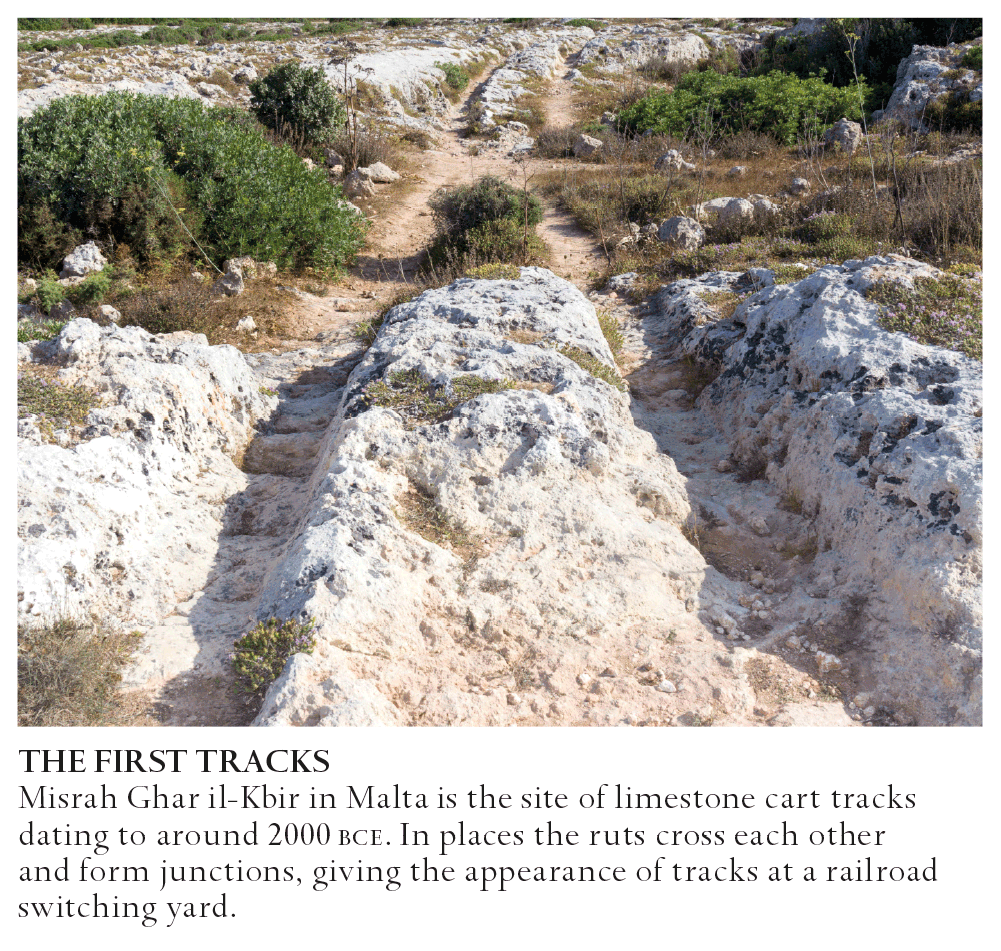

The world’s first railroad, the Liverpool and Manchester line, opened in England in 1830, at the end of the Industrial Revolution. It was the culmination of decades of experimentation with tracks, wagons, and engines, and proved beyond doubt that the railroad was the future of land transportation. But it was also an ancient technology. The wheel had been invented more than 7,000 years earlier, and had soon been given a track. By the time of the Ancient Greeks (600 bce–600 ce), the wheels of carts and coaches were running in specially dug out channels that prevented them from sliding off the road in wet weather, and similar tracks have been found in the ruins of Pompeii and Sicily. Myth has it that Oedipus slew his father when the two came across each other on one such road and argued over who had the right of way.

The earliest image of wooden tracks being used for transportation dates back to 1350 and can be seen in a church in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany. Within a couple of centuries, numerous wagonways (or paths made of such tracks) had been built in Germany and Britain to haul heavily loaded wagons out of mines. The first of these appeared in Saxony, which had become a major tin and silver mining region by the 14th century. Activity in the Saxon mines peaked in the 16th century, thanks to the development of the Leitnagel Hund—a four-wheeled mining truck that was far more efficient than its predecessors. It had an iron bar that projected from its underside into a groove between a pair of wooden tracks, to keep it from veering off course. Operating the truck demanded great skill, and there were inevitably accidents, but it soon revolutionized the German mining industry, making it possible to transport much larger quantities of ore to the surface for smelting. At first, this system was entirely dependent on manpower, but soon horses replaced men, enabling even heavier loads to be moved.

The next development was the introduction of rails for the trucks to travel on. The earliest of these, found in Germany and known as Karrenbahnen, were made of wood, and by the early 18th century, in the coal region of the Ruhr, they had a lip—an L-shaped flange that kept the wagons on the tracks. On some wagonways, the flange was fitted to the wheels of the trucks rather than the tracks, an arrangement that later became standard on the railroad.

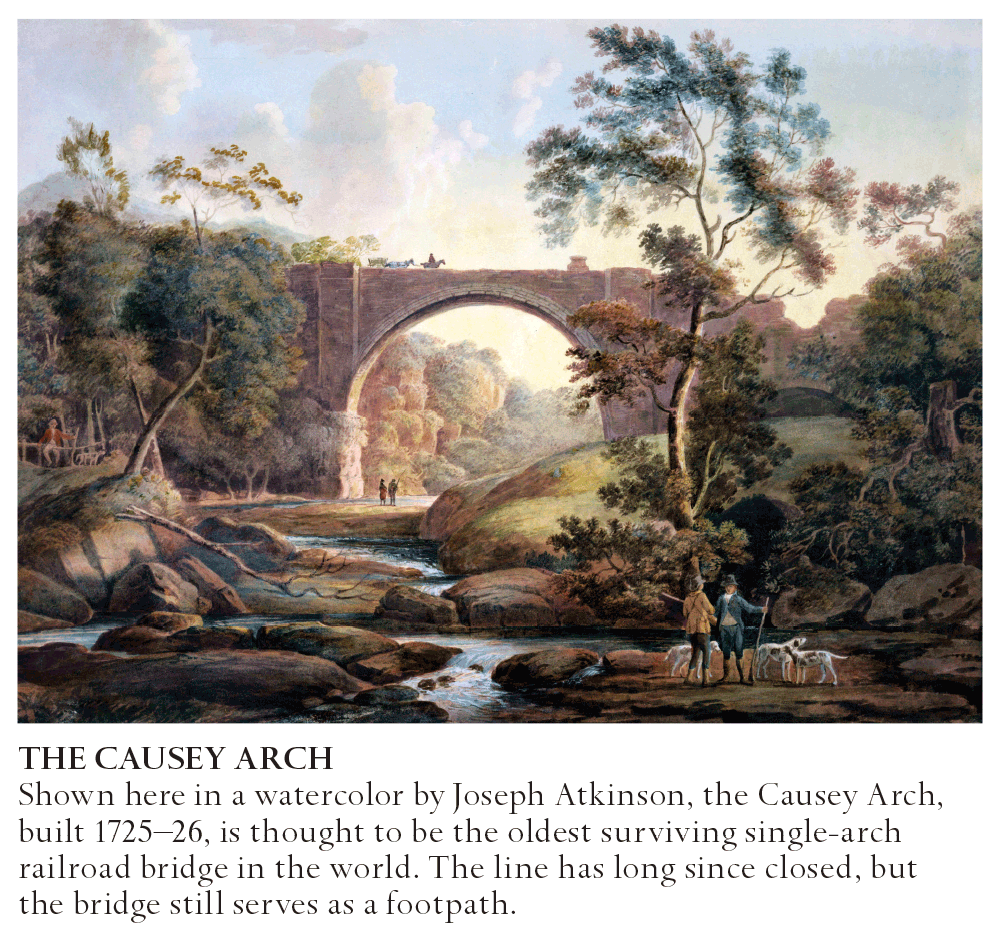

By the time the flange had been introduced, Britain had also developed a system of wagonways. It was based on the German system, but soon became more extensive than its precursor. Britain was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, and its wagonways connected an ever-expanding network of mines to an increasing number of factories, and to waterways that enabled coal and minerals to be shipped even further afield. This transportation system had a huge economic impact on Britain, and both the industrial and domestic consumption of coal increased tenfold between 1700 and the early 1800s. The network that emerged in the northeast of England in the 17th century was so busy with traffic that it became known as the Newcastle Roads. By 1660, there were nine wagonways on Tyneside alone, and several others in the Midlands to the south. In 1726, a group of coal mine owners called the Grand Allies went a step further by linking their collieries to a shared wagonway. They even created a “main line,” the Tanfield Wagonway, much of which had two tracks, permitting a continuous flow of inbound and outbound vehicles. The route linked several pits with the River Tyne, crossing the Causey Arch—a bridge with a 105-ft (32-m) span over a rocky ravine—en route. Costing £12,000 (around £1.5 million or $2.4 million in today’s money), the arch was built by stonemason Ralph Wood and still stands today. At the time it was the longest single-span bridge in Britain, and it is perhaps the oldest railroad bridge in the world. It accommodated two tracks—the “main way” to take coal to the river, and the “bye way” for returning empty wagons—and at its peak, over 900 horse-drawn wagons crossed the arch each day. There were several such wagonways in Britain and the rest of Europe, but cooperative ventures were rare—many pit owners deliberately built wagonways that prevented rivals from reaching the waterways.

It was not until the late eighteenth century that iron rails were first used, notably by mining engineer Friedrichs zu Klausthal near Hanover, Germany. Soon afterward, iron rails were laid to move trucks around the ironworks at the key industrial site of Coalbrookdale in the Midlands, England. The initial idea was to cover existing wooden rails with an iron cap so that they would last longer (they had previously been replaced every year), but advances in smelting technology soon made it possible to construct the entire rails from iron. It was around this time that the words “railroad” and “railway” were adopted for the wagonways of the Midlands, which now carried lime, ore, and pig iron as well as coal. Throughout this period, railroad cars also became larger and were able to carry loads of more than 2½ tons (2.5 tonnes), and the gauge of the tracks (the distance between them) was largely standardized at 5ft (1.5m). This width best suited the horses that hauled the cars (any wider and they were too heavy to pull), and it was close to the gauge that eventually prevailed across much of the world—4ft 8½in (1,435mm), or today’s “standard” gauge.

These iron railroads flourished for about 40 years. At their peak, thousands of miles of iron tracks stretched across Britain, as opposed to the mere hundreds of miles of wooden equivalents that preceded them, and they reached far beyond the coalfields, linking mines and quarries with ports, rivers, and canals. Their main purpose was to transport minerals to the nearest waterway, but a few carried passengers on a casual basis—usually workers hopping on for a ride to or from a mine or a quarry. Some lines, such as the Swansea and Mumbles line in South Wales, provided passenger cars for people, but the main business was freight.

A few canny mine owners devised more sophisticated railroad systems, involving cables and the use of gravity. Ralph Allen, the owner of a quarry above Bath Spa, designed a wagonway on which the loaded cars descending the hill into the city pulled the unloaded ones back up the incline behind them. Such “gravity railroads” became common in the 18th century. The simplest ones used gravity to roll the cars downhill, and horses to pull the empty ones back up. An entirely frivolous example was the Roulette, built for Louis XIV of France in the gardens of Marly, near Paris. The Sun King liked to entertain his guests by giving them a ride on the Roulette. Although technically a gravity railroad, this was really more like a rollercoaster built into a hill. The carved, gilded car thundered down an 820-ft (250-m) wooden track into a valley and then shot up the other side. The passengers boarded from a small, classical building that could lay claim to being the world’s first train station, then three bewigged valets pushed the car to the top of the incline, from where gravity took over, giving the aristocrats a novel thrill.

For all their variety, the early railroads still required horses or humans to pull them along. What they needed was an engine to drive them, and just such a device was being developed. This was the steam engine, which began life as a stationary machine that generated power to drive water pumps, but was soon adapted to provide rotary power to drive wheels. It was a small leap to connect the engine to the wheels it was driving, thus creating a self-propelling, steam-powered vehicle.

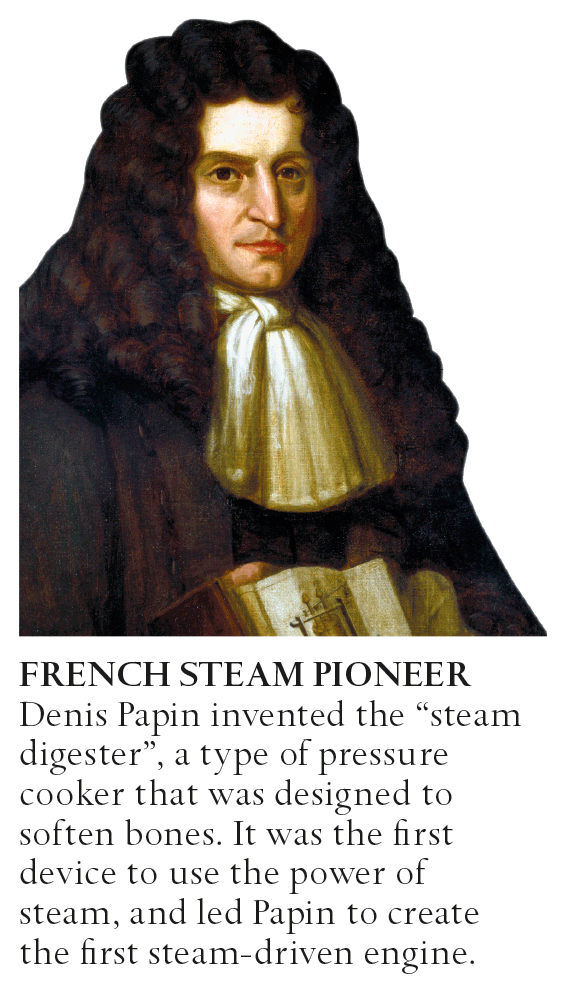

The idea of steam power goes back to Classical times—Archimedes recognized it, and Hero of Alexandria experimented with it—but it was only in the late 17th century that Frenchman Denis Papin harnessed it with his “steam digester,” a crude pressure cooker that he adapted to make an “atmospheric engine”—essentially a cylinder containing a piston that could oscillate under the pressure of steam expanding and condensing. Applying the principles that Papin had documented, Thomas Newcomen, an ironmaster from Devon working in the early 18th century, developed the idea of producing steam engines to pump water from mines, and made 60 of them. After Newcomen died and the patents ran out, engineers copied his ideas and his engines were built in many countries, including the US, the German states, and the Austrian Empire, where one was used to power the fountains for Prinz von Schwarzenberg’s palace in Vienna. However, it was Scottish engineer James Watt who first made steam power commercially viable, by making a series of technical improvements to Newcomen’s designs so that they could be adapted to carry out a wide variety of tasks. He formed a partnership with English manufacturer Matthew Boulton, and soon their engines were powering looms, mills, and ships across the world.

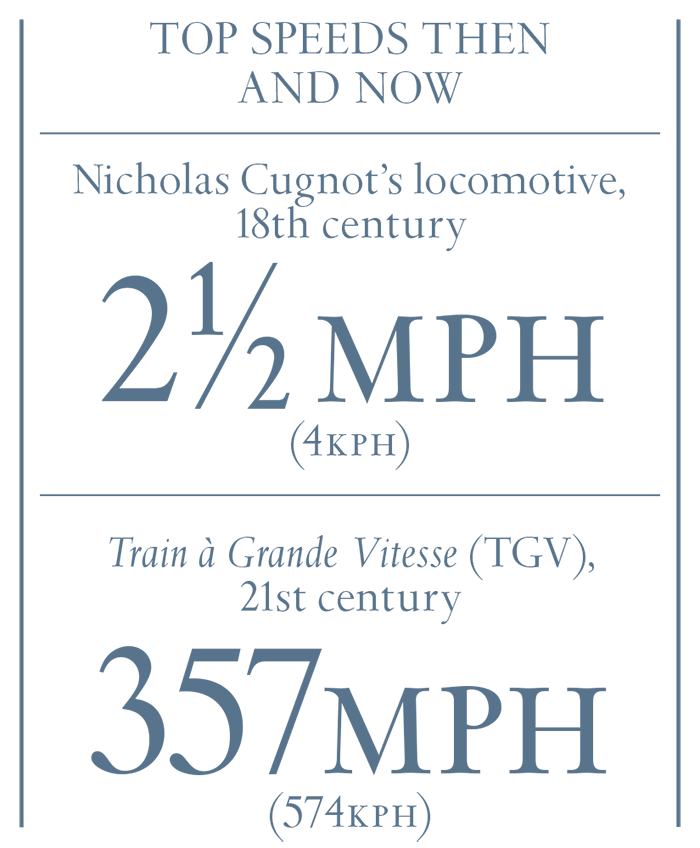

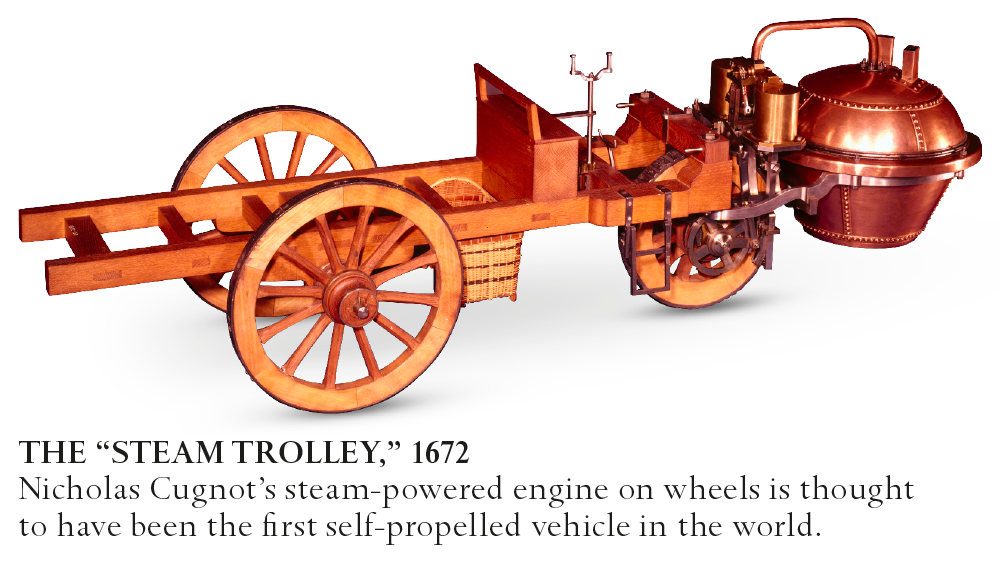

Nicholas Cugnot, an artillery lieutenant from eastern France, made the first attempt to put a steam engine on wheels around 1672, when he designed what he hoped would be a motorized gun platform. On a test run in Paris, his engine propelled itself slowly forward, but then it veered off course and overturned, prompting the city authorities to ban it as a public danger. There were various other attempts, both in Britain and the US, to build steam-powered road vehicles, but they were so heavy they destroyed the roads—a problem that was solved by Cornishman Richard Trevithick, who first put the engine on rails. Trevithick had a setback in 1801, when his “road carriage” caught fire, but three years later he produced a locomotive that traveled at 5mph (8kph) at Pen-y-Darren, an ironworks in Wales. Later still, he demonstrated his invention on a circular track near the present site of Euston station, London, playfully calling it Catch Me Who Can. Like Louis XIV’s Roulette, however, it was more of a amusement park ride than a serious commercial enterprise, and Trevithick went off to develop stationary steam engines for the gold and silver mines of Peru.

By the time Trevithick left England, all the technology needed for a modern railroad was in place. Like railroad tracks, the steam locomotive was slow to develop—indeed, it seemed for a while that horses would power the railroads. It took time for new methods to replace the old, and for many years the railroads were a patchwork of iron and wooden tracks, with steam locomotives being tested while horse-drawn lines were being built. What the railroads needed was a genius to bring these disparate elements together. That genius was civil engineer George Stephenson—a great synthesizer of ideas, who was soon dubbed the “father of railroads.”