Conclusions and Questions

The Mayor’s vision is to encourage people to keep hydrated and reduce the demand for bottled water by ensuring free and easily accessible drinking water is made available across London.

(Greater London Authority, October 2010)1

High quality tap water is embedded in the network of technologies that serve the twenty-first century city. Understandably, our most common experience of accessing that resource is within our homes via our kitchen taps at a fixed price for an unlimited supply (for unmetered customers). The question of that water entering non-domestic spaces, whether private or public, indoors or outdoors, remains a fraught one. As we have seen, the free water access issue has arisen with green activism and politics in the first decade of this century. Even a modest public drinking fountain can therefore represent loaded social attitudes and values in tandem with its mere functional presence.

‘Free access to drinking water across London’, from which the above quote is extracted, is a Mayoral initiative that was launched in 2010 but has had little publicity to date (at least not at the time of writing in October 2012). As we have seen, public water provision is certainly not a new idea. It is worth briefly rewinding through some nodes of the narrative covered in this book’s earlier chapters to establish how distinctions between public and private water evolved.

In the medieval City of London, the Corporation’s involvement in the provision of outdoor water facilities was delivered in a marriage of private finance and public sector management. Conduits depended on the labour of human water carriers to transfer the liquid from public sources to homes and businesses, if it was not consumed outdoors (for instance in the thriving street market on Cheapside). The development of water pumping technologies in the sixteenth century saw the birth of London’s piped water supply corporations, whose founders invested in the creation of the city’s first network technology (as Mark Jenner pointed out). Though it was a long journey for this distribution system to democratically connect all citizens with even basic provision for domestic and sanitary water uses, piped corporate water indoors permanently transformed the basis for why public water sources outdoors might also be needed and used in London.

The seventeenth-century parish pump clearly represented the continuation of a free public water resource for consumption at street level, or for transportation into homes. As the private water network grew during the eighteenth century, bottled mineral water became an elite health commodity for the wealthy, or for desperate hypochondriacs. The commodity was dispensed by coffee houses or sold in exclusive shopping districts. This product was not an alternative to ordinary drinking water, even though it is difficult to ascertain how much domestic tap water was used purely for drinking. We do know that the eruption of public concern about London’s piped water quality did not occur until the late 1820s. At that point, groundwater pumps were still a part of daily life for many Londoners.

Then and until the mid-1850s, the parish pump brand of drinking water was considered by many consumers as superior to piped water, both in flavour and temperature. Post-cholera, the Metropolis Water Act of 1852 gave more of a guarantee that piped water did not contain London’s wastewater, when it could only be drawn from above Teddington Lock and also ‘effec-tually’ filtered. We have also learned that it is somewhat of an urban history myth that alcohol was widely considered to be safer than water by Victorian Londoners, though some may have held that view post-1854’s cholera epidemic and, three decades later, post-germ theory’s discovery. These were moments or spells of concern, rather than pervasive beliefs held over decades. Certainly, the disrepute that the common street water pump suffered as a result of John Snow’s research into cholera’s ‘mode of communication’ was one plank on which the Metropolitan Free Drinking Fountain Association rested its case for a better-managed form of public hydration in 1859. Even though the true motivation for the charity’s foundation, and swift progress, was to cure the drunkenness of the poor and working classes, its literature reveals a prevailing belief that corporate water was safer than the parish pump (this view failed to hinder John Snow’s evidence about piped water’s role in spreading the disease). Clearly, the construction of London’s revolutionary sewerage system in the 1860s also immeasurably transformed the likelihood of sewage and drinking water mixing. A sanitary problem that did dog this period in the city’s poorest communities was the fact that many people shared communal water butts fed by piped water. Therefore, many different, and some unwashed, hands and vessels potentially mingled to spread disease. 1871 marked a legislative turning point for more equitable domestic water supplies: companies were bound to provide a constant supply (even on Sundays) and landlords had to ensure that plumbing was in place to serve all tenants and all storeys of their buildings.

In the scientific and sanitary revolution that dominated the last fifteen years of the nineteenth century, the ethical debate over water’s control, ownership and quality assurance swelled into a full-blown political campaign. This eventually resulted in piped water’s transition from a corporate good to a rateable public service in 1902. Much of the ethical water question was focused on quality for public health. Achieving guaranteed tap water safety to all London homes was the task of the Metropolitan Water Board’s department of water examination — in the first two decades of the twentieth century — under Dr Alexander Houston. His team’s groundbreaking drinking water research made the provision of health-guaranteed piped water inside every Londoner’s home an imperative. Sustaining this standard of production was threatened during the economic climate of war, which led to the introduction of chlorination in 1916. London’s example influenced water engineers and examiners in other industrialised nations and the age of high-tech chlorination advanced during the 1920s. In these seismic changes focused on the democratisation of domestic water supplies, it not surprising that the issue of public fountains, at least in London, was not at the forefront of public analysts’ and sanitarians’ minds, or even architects, nor the new discipline of urban planning (in London anyway).

In the 1930s, the bubble jet fountain’s arrival did show a flutter of concern for the extra-domestic tap. Its design offered a more streamlined, modernist approach to the common drinking fountain suited to indoor workspaces, such as the 1937 Factories Act demanded. We also saw a revival of enthusiasm for public water provision post the Second World War, when London’s parks were revamped and socialist ideas were set into the built environment. The last example is the only government-led public fountain policy that I encountered during my research until that of Boris Johnson’s administration. The drinking fountain has therefore somehow managed to connect the political left and right across many decades as a civic idea.

The nascent scheme of Boris Johnson’s administration is heavily dependent on the goodwill and finance of charitable people (that is nothing new). Even though the scheme has not been publicised, those in the drinking fountain or anti-bottled-water campaigning realm are well aware of the Mayor’s project. Some have even tendered to deliver the vision. There is a catch for them. The Greater London Authority’s (GLA) policy document reveals that proposals have been sought from organisations ‘to assist in the delivery of the Mayor’s vision to provide free and easily accessible drinking water to Londoners on the move at no cost to the GLA or participating stakeholders.’2 Recalling my many conversations with fountain enthusiasts and passionate tap water and anti-bottled-water campaigners over the last two years, I wonder how precariously funded voluntary organisations can benefit from a scheme that offers no finance to support projects? Clearly it would be unwise for an organisation to snub such high profile political support. The attractions of Mayoral endorsement for the voluntary sector’s existing projects offers input from urban planning professionals and powerful publicity opportunities, yet after my research it is apparent to me that creating a viable alternative to the bottled water market in a large city requires significant investment in people, hardware and, potentially, new legislation. An impressive aspect of the GLA’s approach to the issue has been its consultation with various stakeholders, reflecting a respect for the knowledge and experience that already exists and therefore a democratic process, even if the project might well be inherently unsustainable. The niche social sphere of public drinking fountains and free water devotees is not free from its own politics.

John Mills, Chairman of the Drinking Fountain Association since 1982 (the current incarnation of the Victorian fountain charity), sounds a note of caution about the recent interest in public water. ‘Yes, suddenly everyone wants drinking fountains; Boris and then the Lord Mayor and all the local authorities. They think they’re going to do it for nothing. It comes and goes’, he professes knowingly.3 Mills is well aware that the delivery of any drinking fountain is not cheap in terms of materials, project management, maintenance, or even water supply (at least perma-nently). As an architect, Mills has designed drinking fountains in his day job. His architecture practice installed many a vandal-proof fountain for its client the Home Office, in Her Majesty’s prisons. They are one of the few buildings where drinking fountains must be provided by law. In his voluntary capacity, Mills also works on local fountain builds or restorations (when I meet him, he takes me into a room adjacent to his office where he is tinkering with adjustments to a stainless steel outdoor fountain prototype). He feels that community-led fountain projects often succeed where the public sector fails. ‘The local authorities are a bit disinterested [in drinking fountains]’, he states candidly. If this assertion is largely true, it does not bode well for Johnson’s vision. Both historical and contemporary examples, however, do testify to the influence of personalities on the fate of free water missions. Sustaining these projects until they become a social norm after initial passions have abated is more of a concern, from my evidence.

Before his re-election in 2012, the Mayor of London declined my request for an interview to discuss his drinking water vision. Some context for the scheme is provided in his administration’s London Plan (2011) and in the environmental policy, ‘Securing London’s Water Future’. The latter policy reiterates that if free drinking water does spring up, it will do so ‘at no cost to the taxpayer’.4 As precedents, the policy cites six public fountains that the GLA has recently facilitated to some degree, though not paid for directly.5 It is a modest number but a move in the right direction. A sudden proliferation of fountains in public realm design projects is unlikely, when the London Plan states that ‘social infrastructure’, in which drinking fountains are bracketed, should be incorporated into public realm design ‘where appropriate’.6 Appropriate is a rather loose term to interpret.

The GLA’s vague note signals the limits of where the organisation can prescribe the detailed design of places it does not govern. Limits on the state’s authority over the design and management of the public realm is partly a product of neo-liberal ideology that surrendered so much ‘public space’ to the marketplace. More recently, state agencies are fond of sub-contracting the maintenance of the public realm out various service providers. Civic oases are few and far between, regardless of their managers. Importantly in the ‘free’ (or affordable) water access debate, thinking of the often-blurred boundaries that morph between public or private and indoor or outdoor is critical. Spatial nuances matter. For instance, in a model where free drinking water access is mapped on a website and navigated on the internet, or with a mobile phone application and promoted via social media, another layer of public space mediates between the actual café or park fountain, whether privately or publicly owned. Like tapwater.org, Find-A-Fountain and similar international schemes, for example Blue W in Canada, private sector sympathy for free tap water access may provide a more pervasive solution than a public sector revival of civic drinking fountains; precisely because businesses occupy such a large percentage of the extra-domestic spaces we use. One can also see the attraction for businesses to brush up against progressive social movements, or even tout their involvement as a corporate social responsibility exercise. It goes without saying that businesses, business owners and employees are no homogenous mass. Their influence on how the city looks, feels and works is enormous. Individuals’ politics and influence play an important role in determining alliances. Whilst a water access lottery can create dynamic surprises, it also provides no guarantee that a café which joins a free water map will sustain this arrangement if it proves not to suit the business, or if the management, or even ownership, changes hands. Weighing up the evidence amassed during this book’s research, I believe this is a gamble for a public drinking water solution that actually requires legislation to force the hand of both corporations and the public sector. Systemic change is needed to alter the built environment, just as campaigners for better public toilet facilities advocate.

Despite the surrender of much ‘public’ space to commercial ownership, the public sector still retains a great deal of power over the design, use and management of vast swathes of London’s public realm (even by sub-contracts). Mayoral control over the daily operation of Transport for London and therefore the London Underground presents one example of a vast public spatial network that is ripe for a free drinking water trial. As we learned in chapter nine, the Hydrachill tap water vending machine promoters did not succeed in their mission. Embedded in the unit’s design is the inherent contradiction of charging (even nominally) for tap water access, coupled with a pretty undemocratic approach to tackling the broader question of drinking water access on the London Underground, by mooting only one design possibility. Yet these environmental campaigners raised a pertinent question about a powerful strategic target. Architects, planners, product designers, station managers, Thames Water and Tube users would all need to be involved in a sophisticated consultation process. Reminders for Tube passengers to carry bottles of water during hot weather could be rebranded to promote refill facilities within stations or even on platforms (rather than boost spring or mineral water sales).

If a state or a public-private partnership did come to fruition, it would be the first professionally planned scheme of free drinking water in London.

The GLA’s current vision does acknowledge that conventional drinking fountains may not be the sole solution to affordable water access, equally parading the notion of ‘refill stations’. What should the fountains of the twenty-first century look like, who should be responsible for funding them and how might they succeed where others have desiccated? Some recent projects have got the ball rolling and deserve to be mentioned.

Ultimate Designs

During my research for this book, the Royal Parks embarked on an international architecture and drinking fountain quest (there has certainly been a strong zeitgeist propelling this history book into the present tense). Once the Freeman Family Fountain project in Hyde Park was in situ, the Chief Executive of the Royal Parks Foundation, Sara Lom, was hooked on the free drinking water topic.7 About that time, Tiffany ¦ Co. Foundation had set its sights on the Grade One-listed environs of Hyde Park for a project to mark its tenth anniversary. Following a stroll around Hyde Park with the person from Tiffany’s, Lom consulted the Park managers about the prospect of splashing this cash on more drinking fountains. Hey presto, in 2010 a competition for an ‘ultimate drinking fountain’ was launched to find a design suitable for replication throughout the Royal Parks.8 Under the banner of Tiffany’s Across the Water, £1,000,000 was donated for the development of a new drinking fountain template, along with the restoration of 43 historic drinking fountains in the Royal Parks and some decorative water features. In collaboration with the Royal Institute of British Architects, the competition attracted over 150 entries from 26 countries. The specialist design and sanitary-ware expert judges could not settle upon an ultimate design: joint winners had to be declared. Announced in 2011, prizes were awarded to the elegant, elongated bronze Trumpet by Moxon Architects and the granite human-and-dog-friendly Watering Holes of Robin Monotti Architects.9 In January 2012, the first Trumpet was inaugurated with a live fanfare by the Band of Life Guards in Kensington Gardens and a Watering Hole was ready for drinkers to use in Green Park by June. Olympics year was not the reason for these celebrations but it was certainly another motive to get the amenities installed and functioning.

A little trumpeted fact about the Royal Parks is the precedent of an existing drinking fountain restoration in Regent’s Park for the Millennium.10 Originally installed in 1869, the opulent structure of the Readymoney fountain, situated prominently on the main pedestrian thoroughfare of Broad Walk, was bequeathed by a gentleman from India’s Parsee community during the philanthropic fountain craze.11 Back in 2000, anti-bottled water debate was not high on the environmental agenda when climate change was still gaining profile as the issue of the new century. Consequently, this restoration was not heralded for its green credentials. The restored fountain is not just a heritage showpiece. Readymoney dispenses water constantly, particularly on hot days, to Broad Walk’s walkers and bikers. If the

Royal Parks does roll out the ultimate fountains across its hectares of land, the popularity of Regent’s Park facility bodes well for their use. Waste reduction could be significant if drinking fountains prevent bottled water sales in the Royal Parks because 37 million visitors a year reportedly enjoying these environmental lungs.12 In order for large-scale behaviour shift to occur people have to be aware of these amenities. No easy alternatives would help, such as retailers selling bottled water within metres of drinking fountains. On my last trip to Hyde Park, in September 2012, I checked the café outlets and found that they were well stocked with Harrogate Spa water at £1.60 for 500ml. Parting with this sum for a convenient bottle of chilled, quality-assured, drinking water has simply become habitual. Beyond Hyde Park, retailers who align themselves with environmental policies of waste reduction, or addressing food provenance, often still stock bottled water but of so-called ethical brands. Even for those who claim to be environmentally responsible consumers, purchasing water in a bottle seems to reassure them. Conversely, many café and restaurant staff now make a point of serving tap water to show they are doing their bit to lubricate culture, and therefore, behaviour change. Bottled water is usually still available alongside their offer.

Readymoney drinking fountain, Broad Walk, Regent’s Park, 2010.

Author’s own photograph.

This study could not stretch to learning more about the reasons that motivate complex consumer choices in London today, but it is clear that, outside of commercial retail spaces, tap water access is problematic. Long-term, for free tap water resources to dent the bottled water demand and supply equation, they have to become a basic expectation in public places. In short, drinking fountains or any tap water refill facilities must be plentiful and located where they are most likely to be heavily used and well advertised. Only then can they make their transition from novel to normal.

Tiffany’s and the Royal Parks also hope that its template fountains might crop up in parks and public spaces internationally, as a legacy of their competition. The ultimate drinking fountain quest certainly seems to have breathed fresh inspiration into what twenty-first century drinking fountains might look like, how they function and why they should be supported by public space managers. Enquiries from abroad have started, though Sara Lom is coy about divulging from where. Given Tiffany’s involvement with funding the incredible High Line Park, on a disused railway line in New York, these prototypes could spring up in some equally fantastic locations on Tiffany’s home turf, America.

Illustrious fountain locations understandably attract benefactors more readily than more banal public environs. Who, for instance, will fund fountains in railway stations? Some are, admittedly, more glamorous than others. In 1949, the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association announced its triumph of installing fountains in London’s mainline train stations. Euston, St Pancras, Victoria, Liverpool Street, Fenchurch Street and King’s Cross all received donated fountains.13 British Rail evidently had more of a penchant for easing this civic provision than its successor, Network Rail. Now, every available square metre of space in railway stations, save platforms and essential thoroughfares, is filled with retail ‘opportunities’. In the freshly regenerated St Pancras, the cathedral-like station is awash with drinking water choices, as long as you are happy to pay for your choice of bottled water brand from the saturated shop shelves. Nowhere in that bastion of modern, world-class, public space is even a small drinking fountain to be found. Under the new canopy of its refurbished neighbour, King’s Cross, the impressive expanse of a spider’s web-like white steel structure is not a shelter for even a minor hydration amenity. Both stations have been re-designed by internationally acclaimed architectural and urban master-planning practices whose work spans other cities of global stature such as Dubai, Moscow and Shanghai.14 In architectural and engineering projects on these scales, the minor detail of a drinking fountain might simply be overlooked or specifically unwanted by clients. Such omissions pose a deep challenge about how to argue the design of this amenity into daily life, like they must appear in prisons or are more commonly found in primary schools (the latter is, incredibly, not a legal requirement despite the obvious case for sufficient hydration easing mental concentration).15 Contrast King’s Cross station with a similarly traffic filled public building, which has embedded the need for hydration into its very skin.

On the Find-A-Fountain website’s drinking water map, a blue-grey dot on the Euston Road marks the British Library. The dot represents one of only 28 indoor working fountains logged by volunteer researchers across London (not a lot for a population of millions).16 Each floor of the Library contains two robust, yet elegant, stainless steel fonts. They are set into the walls of the communal areas where the library’s users, known as ‘readers’, frequently pass by. These amenities are required for a building where water cannot be permitted to enter the reading rooms containing rare books. What is so notable about the British Library’s drinking fountains is their integration into the current building, designed by Colin St John Wilson architects. Not clumsily piped in as an afterthought; these fountains are stitched into the fabric of the building. Readers and other visitors can sip perfectly chilled water at the spotless fonts either by using the thin, biodegradable paper cone-shaped cups supplied, or by refilling their own vessels. These fountains are heavily used. Located in close proximity to the building’s toilets, they are just far enough from the loo doors to endow them with entirely sanitary associations. Even so, the British Library’s restaurant, cafés and vending machines continue to stock bottled water choices (sadly like the Royal and Olympic Parks). Given the regular use of the amenities, with short queues often forming, one wonders what would happen if bottled water was totally withdrawn from the building’s shops? A riot?

In the current consumer and retail climate, I wonder if we can ever imagine a shop not selling bottled water? Given that even environmentally progressive retailers opt for ‘ethical’ water brands such as Belu or One water, for instance, to propose the complete absence of the product seems revolutionary. Notably, that revolution has started in Bundanoon, a town in Australia just a couple of hours north of Sydney where shops agreed to stop stocking bottled water in July 2009.17 This move might be the only way that customers will be forced to think about why they purchase expensive bottles of water and for stockists to think about how its drinking water profits can be met, if needed, some other way.

Back in central London, just west of the British Library along Euston Road, another dot for an indoor fountain on the Find-A- Fountain website represents University College Hospital. Inside the clinical white and mint-green-hued tower, which opened its doors in 2005, a cathedral-scale atrium with equally vast floor-to-ceiling windows permits natural light to flood in. Tucked in the corner of this state-of-the art medical facility’s entrance, an inconspicuous Water Logic mains-fed dispenser cowers. On an early field trip for this book, I find that it is out of cups. When prompted, the receptionist rummaged around in a few cabinets before producing some plastic disposable vessels. While I should commend any free hydration resource — sighting one was extremely rare at the outset of my research in 2010 — it seems remiss of the designers for such a recent building, and its client (the National Health Service), to not have included a purpose-built public water source functionally and symbolically for human health. Also in the University College Hospital atrium, a newsagent is conveniently situated to relieve those thirsty medical professionals, patients or visitors who, unsurprisingly, fail to notice the Water Logic cooler (as I mentioned, it is rather slight in stature). Whilst I was parked on a stainless steel bench observing the mains fed water cooler’s use over half an hour on a warm day, not one person approached it. Conversely, people emerged from the atrium’s in-house newsagent equipped with their choice of bottled water product. Aqua Pura from Cumbria at £0.90 for 500ml, Volvic at £1.20 per litre, or the charmingly named Very English Spring Water from Kent at £1 for a small bottle were all available. Without conducting an intrusive survey, I cannot be sure if their water purchases were a deliberate choice of bottled over tap water, or potentially for the convenience of a portable container.

Either way, Dame Yves Buckland, Head of the National Consumer Council for Water would lament their choice. In an interview with The Guardian back in 2008, she noted that ‘it’s really hard to get a glass of tap water if you’re in a hospital, or if you’re in a railway station. You’re almost compelled to buy bottled water because there’s nothing else available’.18 She is an advocate of the high quality offer we have on tap. Perhaps at least some NHS Primary Care Trust executives or estate managers tuned into the podcast and were inspired by her words, but without a design commensurate with the grand proportions of spaces such as the grand UCH atrium, the mains fed cooler is practically invisible and therefore unlikely to be used. Good design matters and off-the-shelf solutions do not always fit with the space in question, as functionally adept and low maintenance as they may be.

The Hospital example is even more galling because indoor public buildings are ripe for fountain experimentation. Praise must be bestowed on a neighbour of UCH, the Wellcome Trust medical history centre, which has installed two big, striking stainless steel (chilled) tap water fountains in its library in attractive and, importantly, highly visible units. As a tribute to London’s stunning contribution to the sphere of drinking water’s role in health internationally, the Trust might also consider providing such a resource in its busy lobby, perhaps through a commission of a fountain artwork, to draw attention to the drinking water issue symbolically as well as functionally.

Indoor fountains –particularly in London’s temperate climate –are pragmatic because they provide plumbing, shelter and, hopefully, maintenance staff. If the managers of publicly used buildings, and architects of the future, emulate the principles of the British Library fountain model to any degree, there may be hope that widespread, high quality facilities in public buildings could stimulate a change in the perception of drinking fountains and, consequently, behaviour. On a practical basis, indoor facilities potentially provide a more stable environment and infrastructure to support drinking fountains. Yet that comfort has not stopped some optimists from the challenges of outdoor spaces.

The Great Outdoors

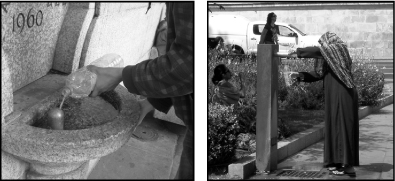

Another researcher has, helpfully, spent some time observing public fountains from the perspective of urban design. Could they, he asked, ‘reduce the city’s carbon footprint’ by reducing the use and consequent waste of bottled water?19 In June 2011, Roberto Cantu’s first case study was on Trafalgar Square. This fountain was bequeathed to the square in 1960 by the Drinking Fountain Association and retrofitted to working order by the Greater London Authority. The amenity is a low-key mural design, only slightly ruffling the smooth lines of Trafalgar Square’s eastern wall. The mural fountain is practically camouflaged in comparison to the way this world heritage site’s bombastic ornamental fountains flaunt themselves. Visually, there is little to draw thirsty people to the free water source, instead of opting for the plethora of packaged water brands in nearby newsagents. Over three hours, Cantu counted a mere thirty drinkers on a mid-summer’s day. One of those drinkers was a local street cleaner.20 The snapshot in Cantu’s report of that fountain user reminds me of Charles Melly’s claim about urban labourers before his fountain was installed on Liverpool Docks: ‘It was almost impossible for anyone to procure a glass of water without going into a shop and buying something — spending, in fact, what he might otherwise have economised’ (1858).21 Whilst his point is uncannily resonant today, the street cleaner’s sup from the fountain is further layered with the irony that Westminster City Council’s street cleansing team, some of who we met in chapter nine, are employees of the sub-contractor Veolia Environmental Services, in turn a subsidiary of French-owned multinational Veolia Environnement which is one of the largest water management operators on the planet.22 Aside from the question of who is controlling and managing the civic provision of ‘free’ water, those who work outdoors are an important user group to consider in the public drinking fountain equation. At least this street cleaner did know about the resource but others may not have realised it was available. Over time, it is likely that word-of-mouth would play a role in promoting the use of clean, functioning fountains such as this one.

Cantu concluded that one reason for the Trafalgar Square fountain’s low level of usage was a lack of signposting to the facility, compounded by its poor visibility. The researcher also noted that the proximity of an open rubbish bin to the fountain was unappealing. However, he rated the device’s automatic sensor highly on his ‘usability’ register, encompassing a range of differently enabled users, whilst pointing out that the 1960s design did not account for the needs of wheelchair users in terms of access.23

Left: Trafalgar Square drinking fountain, 2011. Photograph by

Right: Carter Lane Gardens drinking fountain, City of London, 2011.

Both photographs by Roberto Cantu, reproduced with kind permission.

At the designer’s next observation post, the bottle-refill fountain on Carter Lane Gardens — which we attended the inauguration of in chapter nine — access standards were better. Cantu chalked up 191 drinkers on his chart. Unsurprisingly, it was the hottest day of 2011.24 His data affirms that an attractive, functional fountain will be used given the right weather conditions and the visibility of the amenity, as long as the user has a vessel handy to refill. At the City of London Corporation, there is no lack of investment in maintaining the appearance and cleanliness of the public realm of global finance’s mise en scène. Many local authorities do not have this wealth. Even so, the money potentially saved by eliminating the cost of clearing up and processing water bottles as waste or recycling is one avenue for arguing the financial sense of installing and maintaining some strategically-located fountains. Routine maintenance, of a high standard, is critical to promoting the use of facilities, if built, and therefore potentially stimulating behaviour to change from bottle to tap water consumption. A conventional promotion campaign could also raise the profile of the modest fountain as a topic for public debate.

Funding-wise, Thames Water’s shareholders might be convinced to part with some of their profits for public fountains as part of a corporate social responsibility strategy? In the financial year 2010–11, Thames Water Utilities Limited made a profit of £225.2 million and in 2011–2012 the corporation’s Chief Executive Officer, Martin Baggs, earned almost £900,000 in salary and bonuses combined.25 The cost of a few, or many, drinking fountains is clearly a drop in the ocean of Thames Water’s profit margins. It would certainly be an appropriately civic gesture from the company’s shareholders to Londoners, not to mention being a positive endorsement of its excellent product. Another incentive for the water industry to engage with drinking fountains is, perhaps counter-intuitively, to promote water conservation.

With good designers, materials and maintenance, drinking fountains should play an important role in rising to the twenty-first century’s climate change and freshwater challenges. The fact that we only drink what we need from a fountain makes it sustainable both in terms of reducing bottled water waste and freshwater use. A well-designed, well-located, well-maintained drinking fountain gives appropriate access to ‘little water’, to invert Zoe Safoulis’s term for the inhumane scale, and socially detached stance, of ‘big water’ engineering.26 The social historian John Burnett reminds us in Liquid Pleasures (1999): ‘Water remains the principle liquid drunk in Britain, although this takes a very small proportion of total water usage of 135 litres per person per day.’ (Large uses are activities such as toilet flushing, bathing or showering).27 The 1995 survey that Burnett quotes found that average tap water use was 1.14 litres. This figure was not broken down into water used in the home or outdoors but, even so, we know that the quantity of public drinking water that we need to counter bottled water is small fry in the bigger freshwater demand equation. More problematic is the promotion of unnecessary levels of hydration to rationalise the pallet-loads of bottled water that are shifted from juggernaut, to warehouse and newsagent fridges daily.

In a seriously water-stressed place like London, the idea of providing a resource where people can drink just enough for their hydration needs fits with forward-looking strategies of organisations such as Waterwise. Bottled water-sized packages are prescribed portions of water, but, when using a well-designed fountain, we can have agency over the quantity water we consume with the simple push of a button. Freshwater resources sucked out of the ground into bottles hundreds of miles away can be saved, as can the energy to transport them to us and for refrigeration. Water is heavy, as so many people around the world well know. Whilst refilling and carting around water is not a problem for some, for others who are already cycling with heavy loads, walking with luggage, or dealing with pushchairs and associated baby paraphernalia, water is an extra burden for the pedestrian and not an inconsiderable one. It is also easy to forget to bring water out, hence many impulse sales of bottled water (these add up over the years). But in order to make these choices, we have to know that drinking water is widely available and accessible, everywhere beyond our kitchens.

A hydration lottery will not work, as people will simply revert to bottled water. The bottled water market relies on our instinctive craving for water, often in favour of any other hydration product. For public water resources to change London’s consumption and waste habits significantly, and those of other cities or towns in Europe and beyond, fountains are not only needed as amenities in parks, they need to be provided in indoor, or at least sheltered, locations in the city and beyond; such as motorway service stations, shopping centres, supermarkets and train stations to name but a few places. Where is free drinking water to be found in the vast swathes of space owned by Asda, Sainsbury’s, Tesco or Westfield? With decent budgets from such wealthy corporations, a whole new fountain, public tap, or refill station lexicon could be unleashed (I have a particular fantasy about rain-water harvesting drinking fountains that, somehow, purify in situ). Through planning legislation, the Community Infrastructure Levy could certainly be another fountain funding stream, which all developers of publicly used buildings must pay towards civic infrastructure (at a fee per square metre). Section 106 fees that property developers must pay to local authorities are also a source of cash for this much-needed ‘social infrastructure’.28 How that need is translated successfully into the built environment for the benefit of users and the managers of buildings and public spaces does need further analysis and research to ensure sustainable solutions. Legislation may well be the only way to force those owners of our most frequently used daily spaces to actively promote the de-commodification of drinking water and make one healthy contribution to a more sustainable city. Similarly to the hospital example in terms of scale, supermarkets or shopping malls would need to install a highly visible fountain in order to distract any consumers from bottled water.

Drinking water ethics

Through whatever combination of fountains, refill stations, or water transported by individuals from their own homes, a permanent public drinking water revolution for London could actually eliminate the need for bottled water. A perpetual flow of piped tap water and bottled water into the city is simply not necessary. Of course, this mirrors the story of many packaged, highly profitable consumables but the difference with water is that we really do need some of it, if not in those quantities or through those modes of production.

A mirror of the overlap between this city’s public and private space interests was seen in the planning for the 2012 Olympic Games, particularly because of its public-private funding partnership. Some eco ambitions were thwarted by Coca-Cola’s sponsorship which dictated that its product had to be supplied alongside free tap water. Tales from inside the Olympic Park recounted impossibly long queues for the free water sources, with one of my interviewees explaining how her mother had given up the wait and bought a bottle of Schweppes Abbey Well, in order to make it to the next event (tickets were hard fought for).29 Culturally, there is a certain resignation to parting with £1.60 for a bottle of water, simply because the products are so ubiquitous and it is hard to imagine a time when they were not available, like so many disposable consumables. Positively, ticket holders at London 2012 were permitted to bring empty plastic bottles into the Park. Also, at the temporary hydration stations, no cups were provided to help combat unnecessary waste production. The efforts of the sustainability people working inside the Games can be felt in these important, intelligent choices. My inside observers concurred that demand for the free water well exceeded what was available during busy spells. If bottled water had not been available, more free drinking water sources would have been essential, particularly in the light of the airport-style security preventing ticket holders from bringing their own tap water into the venues. The strain between sustain-ability rhetoric and the stake of, some, sponsors is evident in the twin drinking water arrangements.

Coca-Cola met potential accusations of hypocrisy head on, in a now-familiar style of corporations acknowledging inherently unsustainable practices. A form of reverse psychology is employed to green-wash what is really un-green-washable. Take this statement in one of London 2012’s sustainability reports: ‘Millions of drinks will be consumed during the Olympic and Paralympic Games and the company recognises that their product packaging will contribute significantly to the recyclable waste stream. The Coca-Cola Company is therefore working in partnership with LOCOG to develop a compelling campaign to encourage visitors to recycle.’30 The corporation certainly seemed confident from this statement that the tap water choice would not dent its sales at the Games. This paradigm shows how ludicrously profitable drinking water has become in London, and globally. One persistent defence from bottled water manufacturers is that their product is essential in emergencies, which is unfortunately true for places such as Haiti. There, the 2010 earthquake led to an outbreak of cholera which is reported to have caused more than 7,000 deaths and has been mired in controversy about where responsibility for the cause and cure for the disease should lie. The United Nations itself has been accused of causing the spread of cholera.31 It is immoral and unacceptable that such a poor nation has to rely on bottled water for an assured supply of safe drinking water. Like many places where water quality cannot be guaranteed, the poorest people are forced to buy bottled water or use the services of water ‘vendors’, who profit from these endemic infrastructural malaises. Those are political and environmental failures that most developed world nations are extremely fortunate not to confront.

Drought is a natural disaster that must be considered in the U.K. and other developed world nations and hence the concept of a national water grid is rightly on the environmental, political and water industry agenda. That is simply not a drinking water issue because of the quantities of consumption in question. As stated at the beginning of the book, hosepipe bans are an inconvenience but not being able to pour a glass of water out of the tap is practically unimaginable and could soon be solved from alternative sources without the need for emergency bottled water, with appropriate planning.

As well as countering the flow of bottled water products, issues of social justice and welfare also need to be factored into the hydration equation even in industrialised nations. If we forget to refill a bottle from the tap to bring outdoors with us, should our only hydration recourse be to pay an unethically high price for drinking water, or to beg an employee in a café to hand over some free water? What if that thirsty person is ill, heavily pregnant, elderly, a toddler, penniless or homeless? Or what if that person is none of those vulnerable categories, but simply a thirsty citizen in need of a modest quantity of water to rehydrate? Water is fundamental to maintaining all of our bodily functions, so how can citizens be effectively denied access to it? How does the United Nations landmark announcement in 2002 that access to safe drinking water is a core human right translate to the context of the developed world globalised city?

Published in 2001, economist Riccardo Petrella’s polemic The Water Manifesto argues for a World Water Contract to ensure basic and consistent access to water ‘for every human being and every human community’.32 His critique of the transition of water’s management in many countries from the public to the private sector and its valuation in market-based terms, rather than as a ‘non-substitutable common social asset’ remains valid in

England and Wales today (notably not in Scotland, where the water and waste-water industry was not privatised in 1989). As a Dubliner originally, I was downcast to read in Petrella’s account of water’s commodification that an international agreement about re-categorising water as an ‘economic asset’, convened by the United Nations, was forged in 1992, in my home city.33 Less than ten years later, this economist was making a different plea to the international community, on the basis that water is not interchangeable with other commodities, particularly water needed for drinking. In Petrella’s words: ‘Basic access for every human being means that he or she can enjoy the minimum quantity of fresh drinking water that society considers necessary and indispensable to a decent life, and that the quality of this water is in accordance with world health norms.’34 His thesis has been hugely influential. In 2003 the United Nations published its conclusions from a committee interrogating drinking water’s place in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: ‘The Human Right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity’. The Committee further resolved that ‘the right to water is also inextricably linked to the right to the highest attainable standard of health’.35 Even though we might imagine that the need for this right to be addressed by the United Nations was legitimately focused on global injustices, particularly between the northern and southern hemispheres, the committee elaborated that the organisation had been ‘confronted continually with the widespread denial of the right to water in developing as well as developed countries’ (I emphasise that the health inequities between countries with and without adequate water and sanitations are intolerable and unjust).36 The United Nation’s recommendation about water rights within the covenant does, however, define the limits of that human right to water spatially to the ‘household, educational institution and workplace’.37 If this spatial definition was broadened, then it could legally oblige public and private bodies to provide drinking water in the environs they own and manage. Employers, for instance, have to ensure that sufficient drinking water is available for their staff, as a statutory health and safety requirement.38 Hence the success of water cooler companies whose workers can be seen unloading their wares from vans in most of London’s office districts on a daily basis. Water coolers are children of America.

Fountains Abroad

Across the ‘pond’, there has been prolific anti-bottled-water activism in the last decade. The town of Concord in Massachusetts followed Bundanoon’s example and banned bottled water from its shops in 2010.39 A particularly vocal critic of the bottled water industry’s ethics and the decline of public drinking fountains is the water scientist and environmental campaigner Dr Peter Gleick. He is clearly incensed by the ubiquity of bottled water in his book Bottled and Sold: ‘Water fountains used to be everywhere, but they have slowly disappeared as public water is increasingly pushed out in favor of private control and profit.’40 Gleick concludes: ‘If public sources of drinking water were more accessible, arguments about the convenience of bottled water would seem silly.’41 The environmental journalist Elizabeth Royte is equally incensed by the murky ethics of bottled water production. Her book, Bottlemania cites aspirational water drinking as one reason for the success of imported products in America when she recalls a time when ‘ordering imported water was classy; it improved the tone of a dinner party. Once that idea took hold in America, there was no going back’.42 Some anti-bottled-water activism in the U.S. has focused on the use of oil in bottle production. For instance, the documentary Tapped exposes the horrific health impacts of poor air quality on residents living beside a plastic bottle manufacturer, with evidence of high rates of premature deaths from cancers associated with this industry’s production of air pollution.43

The Pacific Institute, of which Dr Peter Gleick is President, recently launched a website, in partnership with Google, to map America’s public drinking fountains and a downloadable app, called WeTap Map. At the time of writing, the project is in its infancy but it adds to information in the public domain about free water sources and is a stimulus for viral communication.

On WeTap’s blog, one enthusiastic contributor has posted a link to a list of Paris’s public fountains. Tourist blogs about Paris wax lyrical about the free hydration offer of Les Fontaines Wallace, or the Wallace Fountains. Their benefactor, the Anglo-Frenchman, Sir Richard Wallace donated the fountains to Paris following the destruction caused to the city during the Franco-Prussian War in the 1870s. Sir Richard was politely offered advice from the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain Association but the playful aesthetic of his fountains suggests that he did not pay much heed to the English style of public fountain.44 His interpretation of the amenity type was rather different from England’s sombre granite fountains. Generously, Wallace personally financed over a hundred fountains to be built across Paris and his payback has come with immortalisation in a much-loved social architectural offering. They still serve the city today. Les Fontaines Wallaces’ distinctively decorative style in delicately wrought, yet robust, ivy-green cast iron features four Caryatids — female figures employed as structural supports — representing kindness, simplicity, charity and sobriety, who guard the precious public water. These fountains are lauded as a part of Paris’ architectural heritage and benefit locals and tourists alike. Their visual flamboyance seems to attract users and suggests that a little novelty factor can work well in some contexts. Also, the water they dispense is evidently trusted. A recent visitor to Paris told me that she and her extended family availed of the Wallace Fountains on their holiday trek around the city over several days and saw others using them constantly. She recalled that they did buy bottled water initially, but then re-used those containers once they had located the fountains (not an uncommon practice and a reason why the refill bottle market jostles with lots of great designs, but, like umbrellas, water containers tend to go missing).

Given that Paris, like London, is awash with bottled water, it seems naïve to imagine that decades of habitual purchases of mineral and spring water will suddenly cease. My recent visit to Athens during the sweltering summer of 2012 showed a city also awash with bottled water but, curiously, there is a rather humane pact between sales outlets that all bottles retail for €0.50. This price is considerably less outlandish than bottled water sells for in most capital cities. In Greece’s dismal economic situation, even that price seems immoral when temperatures are 38 degree centigrade plus. I spotted a sole public fountain during a week in Athens (admittedly, that was not the focus of my trip), at an entrance to the national gardens. The amenity was not in great condition but one man, who appeared to be homeless took a long drink from its upward pointing jet. I followed his lead. The water tasted good, particularly because that gulp was free. A fridge in the kiosk just next to the fountain glistened with rows of water bottles.

If Athens had its own Fontaines Wallaces, would bottled water sales fall in the summer months? Unfortunately, no such studies have been conducted (at least that this researcher has located). Studies of Geneva’s and Rome’s rich public water bounties could provide valuable data about water drinking behaviours. At least those cities have retained their historic civic fountains, so people there are free to choose whether to trust public water supplies or pay for bottled water. In Spain, such architectural heritage has rapidly declined according to a group of artists based in Madrid. Luzinterruptus claim that 50% of the city’s public fountains have desiccated during the last thirty years. To highlight their demise, the collective staged a provocative guerrilla artwork for four hours in January 2012 and called for the restoration of the city’s stock of drinking fountains. The temporary protest-cum-artwork Agua que has de beber — which translates literally to ‘water you must drink‘45 — was mounted during the night for maximum visual effect. Cascades of small recycled glass jars were attached to the spouts and dry bowls of four unused public fountains and illuminated to simulate flowing water.46 At the base of the objects, more identical jars spread out into a ‘pool’, seeping into the street. Skilfully, the image simultaneously conveyed both water waste and the unnecessary flow of water bottles into the city, and the waste the latter produces. Photography of the protest preserves the sculptural interventions on the artists’ website for further dissemination after the fountains carcasses were restored to their normal state of dysfunction. The artwork’s lament for the loss of simple civic amenities more broadly symbolises the decline in the management of public spaces for citizens’ benefit. It also reminds us that not all ‘progress’ is good.

Return to the Thames

Luzinterruptus is unlikely to have received an invite for its members to travel across from Madrid to Barcelona for Zenith International’s 9th Global Bottled Water Congress in October 2012. There, The Coca-Cola Company, Danone and Nestlé Waters, amongst others, were scheduled to discuss how to keep on top of the market ‘by unlocking more natural value’. 47 In November 2012, Zenith International’s tour continued with the UK Bottled Water Industry conference in London, entitled Green Light for Bottled Water. Alongside brand development tips, delegates could attend a session on ‘improving recycling’ with a speaker from the Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (yes, the government department), or hear how to reduce the environmental impact of plastic packaging with a senior technologist from the Waste and Resources Action Programme (also a U.K. government agency).48 Positively, credible sustainability advocates are on board the corporate water road show; however their presence is also an admission that bottled water is with us for the foreseeable future. Rather than the ‘polluter pays’, this policy seems to be ‘work with the polluters’ because we have no hope of stopping them.

On a website promoting the UK Bottled Water Industry conference, the sole image is a night shot of the London Eye.49 The photograph shows the illuminated big wheel structure glazed with a neon-pink hue in a tranquil expanse of the Thames. The river itself is not shown in a critical light. In fact, it looks clean, even pristine in a shade of peaceful midnight blue. After my long trawl through London’s drinking water history, I cannot help but find the choice of image somewhat ironic. A bottled water conference for London is not advertised with the aid of an image of a rural water wilderness hundreds of miles from the city but with a thoroughly urban representation of the city’s water source. Actually, to me, the image is an apt reflection of the parallel drinking water stream that flows wastefully on into the twenty-first century city’s second decade.

I remain optimistic that the Water Framework Directive’s implementation will improve the quality of London’s raw water sources by 2015 and, in doing so, begin to modify the environmental cost of water treatment practices in this century. But I do not believe we should idealise the era of pre-water treatment era. This industrial system has evolved in a large part to pragmatically cope with an industrialised society. Even all being well on the pollution front, we have to consider the impact of natural or industrial disasters on water catchments, for instance those increasingly wrought by climate change, such as flooding. Those freshwater ‘gardens of Eden’ owned by the bottled water companies presents land ownership and water abstraction licence issues that need further scrutiny, globally. In terms of the Water Framework Directive, citizens should have free access to information and progress on that monumental project. If raw water intended for drinking is effectively protected from pollution and treatment measures are reduced, the argument that bottled water is superior to tap water will seriously falter.

As an ordinary water consumer, I would have been completely unaware of the radical ambitions of the Water Framework Directive without my foray into the professional, jargon-laden spheres of the Environment Agency and the water industry. Understandably, those organisations are the preserve of engineers and other scientists but water, and particularly drinking water, is too critical a natural resource for consumers not be consulted about very openly. The privatisation of the water industry in England and Wales is unlikely to be reversed any time soon, but the boundaries of that private preserve need to be tested so that more scrutiny and dialogue about how that industry relates to the city and its inhabitants can take place for drinking water and other freshwater uses. Behaviour change alone cannot solve problems that are inherently systemic. In my struggle to find a neat ending to tie up this book, I realise that London’s water questions are still far from resolved in the twenty-first century despite incredible progress on some fronts.

London’s private and public drinking water is a vital node in the global freshwater conservation challenges of this century. I can only hope that this contribution to those global conversations offers a springboard for others to dive into these questions and to surface with some fresh suggestions for the future of this city, and for other cities.