Wells, Conduits and Cordial Waters: drinking water sketches A.D. 43–1800

Your Petitioners doe humbly desire, for that there is great defect of water, in the said conduits: and that it is a generall grieuance, to the whole City…

(Water-Tankerd-Bearers, Citie of London, 1621)1

From the Roman City and throughout the incremental introduction of piped domestic water from the late sixteenth until the mid-nineteenth century, most Londoners’ water depended on vast quantities of daily labour, either expended by them or by others on their behalf. This chapter draws a historical map of some of the urban spaces tied closely to water access and traces when and where the issue of water quality arose. Traversing this expansive historical terrain, we will briefly dip into larger subjects, such as the early mineral water market and spa culture, which other researchers have documented in depth. My aim now is to set the drinking water scene in pre-modern, early modern and eighteenth century London. From here, some of the key themes in the city’s modern drinking water story begin to ripple out.

Londinium

Early Britons’ settlements on the river Thames pre-dated the foundation of the Roman city. This riparian, or riverside, community had no shortage of running water at its disposal. And below the ground, former waterholes contain material evidence of a spiritual culture. Vessels recovered from these underground pits, dated as early as 1500 B.C. are believed to have been offerings to the ‘netherworld of spirits’.2 Remnants of decayed food, tools and weapons found within the watery subsoil played a symbolic role in this community’s culture. After A.D. 50, pre-Christian forms of water worship persisted as Roman beliefs mingled with these pagan practices. For the Mediterranean inhabitants of Londinium, some may have viewed the Thames simply as a conduit to the mythological River Styx, a realm of the Gods. For instance, remains of the upper body of a marble sculpture of a male, from circa A.D. 150, are thought to represent a water god who inhabited the liminal space of the river, hovering between life and death.3 Water’s spiritual associations did not, however, displace its practical role in daily life. Plumbing was an important characteristic of Roman civilisation.

Geographically and geologically, ancient London was by no means parched. The Thames was naturally important for trans-portation; however the tidal river was not a likely freshwater source. Underground water supplies (aquifers) served that need, as well as two other rivers (surface water).4 Unlike other Roman cities, renowned for their hydro-geological engineering feats; Londinium had no need for aqueducts. The contents of the Chalk, London’s vast groundwater source, lay just metres below layers of brick earth, sand and gravel sitting above the impermeable London Clay. Within hours of digging, a task most likely performed by a slave, the water swilling underfoot added to resources from the Fleet and Walbrook rivers. The contours of the city’s two hills also meant that, in places, water rose very close to the surface.

Londinium was the only urban centre in Roman Britain with a watercourse running through its city centre, the Walbrook.5 On a recently revised map of Londinium (by the Museum of London), the Walbrook river and many tributary streams can be seen snaking under the ancient city’s walls and between the amphitheatre and the basilica, with the Temple of Mithras situated on its banks just before the river flows into the Thames (near modern-day London Bridge). Archaeologists are certain that Londinium’s urban designers were more than aware of the hydrological wonder underground and recent discoveries endorse their view.6 However saturated the ancient city might have been, were its inhabitants really water drinkers?

Vitruvius, a Roman architect, is the first recorded architectural critic and theorist in the west. He promoted water’s centrality to a high standard of living. In fact, he dedicated an entire chapter to the substance in his famous architectural treatise: Ten Books on Architecture (circa 20–30 B.C.). Even though Vitruvius wrote long before Londinium was founded and he wrote in balmier Mediterranean climes and drier landscapes than northern Europe, it is thanks to him that we have clear evidence that in Roman culture water use was not confined to the indulgent bathing practices of a leisured elite. They were definitely drinking water.

According to Vitruvius, water was not only consumed as a wine-diluter to keep Bacchus at bay, it was also consumed neat: ‘Water, offering endless necessities as well as drink, offers services all the more gratifying because they are gratis’ (his interpreters clearly enjoyed his intended pun).7 For Vitruvius, not all water was equal. He believed that the rainfall of stormy weather was particularly vital as a liquid. The architect’s writing offers strong evidence of Roman cultural beliefs that water was a substance of purity and health because of its ability to cleanse the inaccessible inner landscape of the body. Ingesting healthful waters, according to Vitruvius, could even cure defective internal organs. And Athenians apparently distinguished between the water sources from which its citizens could safely drink, and those for external functions such as washing.

Ancient springs were not always thought to be pure and nature’s raw bounty was recognised as both blessed and cursed. Environmental pollution caused by poisonous metals such as gold, silver, iron, copper and lead were known to seep into water supplies in certain geological areas. One Persian spring was even reputed to have caused its drinkers’ teeth to fall out.8 Drinking water also had pleasurable associations for Vitruvius. Some springs were thought to make people drunk ‘even without wine‘, whilst other sources were renowned for exciting erotic arousal.9 Whatever its effect, Vitruvius’ sommelier-like description of water endowed the liquid with a flavour spectrum ranging from a touch on the bitter to the outright delicious.

High Street Wells

One beverage that was certainly consumed in the Roman City of London, and in no mean measure, was wine. Barrels were shipped up the Thames’ estuary from Germany and Spain, in vast quantities. Those barrels provided the materials for the construction of one system of wells (a second type had square shafts lined with timber). Once the wine had been quaffed, re-using the barrels involved removing their tops and bottoms so that the tightly bound strips of curved wood could be employed to reinforce the earthen walls of the well-holes reaching down into underground sources.10 Remnants of this system are preserved in the Museum of London, including fragments of a ladder used for descending into these watery shafts. One can easily imagine the staccato rhythms of bodies disappearing and reappearing from a cluster of eighteen wells, near contemporary Queen Victoria Street (it adjoins Mansion House tube station with Blackfriars bridge).11 Although most of Londinium’s wells are thought to have been associated with individual buildings, this cluster formed a definite centre for communal water access. Queues and jostling may also have occurred at this cluster and, no doubt, gruelling journeys with water vessels from the source to homes and places of work. Remains of plumbing infrastructure near some wells also suggest the conduction of freshwater supplies direct to local buildings. Pipes were constructed from different materials to visually distinguish the flow of fresh, inbound water and used outbound water from the city, with impressive sanitary nous.12

Wells were not all used in the service of the greater civic good. Some wells were entirely private and relate directly to the social inequalities embedded in Roman civilisation. Location was everything. The labour cost, in terms of time and energy, for those who had to transport their water from the public source to the point of use can only be imagined. As the classical historian Peter Marsden summarises: ‘There were three classes of people in Londinium apart from Roman citizens; the free, the freed and the slaves. The native Britons, who were free but had none of the special rights of a Roman citizen, were known as the Peregreni.’13 The Peregreni were essentially Londinium’s working class.

These inhabitants’ daily lives forged a very inner-city experience. They lived in tightly packed timber-frame ‘Mediterranean style’ houses. At Londinium’s height between A.D. 100 to 200, many of the city’s population — anywhere from circa 24,000 to 45,000 people — were working iron and leather for a living.14 This industrial activity was concentrated in the north of the city, close to modern-day Moorgate, on the banks of the Walbrook. Waste from this industry saw vast quantities of materials, such as iron slag and the by-products of tanning, entering the watercourse. Downstream of the tanners and ironmongers, the Walbrook’s contents would not have been appetising to dip into, no matter how dehydrated those workers were. Archaeologists have deduced that the underground water-fed wells, constructed a few metres away from the Walbrook, were an important source of drinking water. It seems plausible to imagine that they provided refreshment for these workers and for local residents own freshwater needs (both cooking and drinking).

Whilst the Romans and the Peregreni were in the bacteriological dark, we know from Vitruvius’s writing that the correlation between illness and the consumption of polluted water was understood on some level: ‘Deadly types of water can also be found; these, coursing through harmful sap in the earth, acquire a poisonous force in themselves.’15

Aqua Superior

Remains of a high-tech well in Londinium, one of two unique to Roman Britain in the city, suggest that effectively filtered water was pumped out of the earth close to the amphitheatre on Gresham Street.16 Although the engineering ingenuity of this ‘water-lifting mechanism’ sank to a similar depth to the crude ‘barrel’ wells, a great quantity and quality of water could be guaranteed thanks to slave labour. Operated by a chain-and-bucket system from above ground, this water would not be muddied by the boots of a person climbing down into the well shaft for instance.17

Only discovered in 1988, today one can roam around the amphitheatre’s ruins below the Guildhall Yard. Up to 6,000 spectators could be found here baying for blood at gladiatorial spectacles, or participating in less gory religious activities.18 Either pursuit equalled the production of lots of thirsty spectators. Calculations show that the mechanical wells would have produced two litres of water per second, or seventy-two thousand litres over a ten-hour period. Though the technology’s chain-and-bucket system has been praised for its early engineering ingenuity, it has also been noted that constant slave or animal energy was needed to turn its vast wheels.19 How much of this water was for drinking only cannot be known for certain. For instance, there was a bathhouse just south of Gresham Street that also needed a water supply, but evidence suggests the bathhouse was actually served by cisterns that drew directly from the underground supply.20 However, a design to extract water at a point of naturally high filtration through sand filtration suggests the organisation of the resource into hierarchies of quality for different uses and users. Possibly, the best drinking water in Londinium was reserved for those in the best seats in the amphitheatre. Labour was essential to the production of both that high quality commodity and water drawn from less high-tech wells. Although Vitruvius wrote that water was gratis, this human cost of hydration was evident in this northern outpost of the Roman Empire.

No association has been made between Londinium’s decline and waterborne disease. But decline it did. The ancient city is believed to have been uninhabited after the gradual ebb of Roman occupation, circa A.D. 450, until the first Christian Saxon settlers arrived in the early 600s.21 During that interlude, dust settled over grand villas and wells alike.

Middle Ages

In that transition period, some minor evidence of early-Saxon presence in the former city has been detected — such as a lost brooch — but these traces were scattered by transient people.22 New foundation stones were only laid once more when Christian London became the seat of an archbishop in the seventh century. Evidence that water drinking was a common practice beyond London came in the form of bronze cups suspended from posts alongside springs on the ‘highway’.23 These cups were gifts from King Edwin of Northumbria, permitting the traveller to enjoy raw water supplies freely.

Saxons reoccupied London in the sixth century as Britain’s new religious culture deepened.24 St Paul’s Cathedral was founded in A.D.604 and during the eighth and ninth-centuries Christian beliefs were further inscribed in churches of a more modest scale inside the boundaries marked by the old Roman walls. Extramurally, Westminster was defined as a community in A.D. 785 for ‘the needy people of God’ and an order of Benedictine monks settled under the watch of St Dunstan, Bishop of London, in A.D. 960.25 When Westminster Abbey was completed in A.D. 1065, rudimentary plumbing conducted water for the ritualistic washing practices of the Benedictines. Remains of a tap excavated from the original site are believed to originate from a ‘water-filtering system’.26 No doubt general matter such as leaves and insects had to be strained away, but it is possible that water for cooking and drinking was also treated to some aesthetically superior version of the raw good.

Back inside the walled city, citizens of the City of London were granted a charter outlining their rights under William the Conqueror’s administration in 1066. During that century, the only hard water evidence of note in the Museum of London are water-collecting buckets dated from the Norman period, suggesting that new wells had been sunk or rediscovered. By 1215 a government for the Square Mile, with a Mayor and an elected Corporation was in place.27 Extramurally, parish ward boundaries, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields and St Dunstan, were drawn up during the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. By the end of the twelfth century, Christian London’s population was estimated at between 20,000 and 25,000 people, making it the most populous, and wealthiest, city in England.28

Twelfth century author William Fitz Stephen wrote of social life at ‘special wels in the Suburbs, sweete, wholesome and cleare, amongst which Holywell, Clarkes wel and Clements well, are most famous and frequented by Scholers and youthes of the Citie in sommer evenings, when they walk forth to take the aire’.29 Two of these wells related to locations of important nunneries founded in this century. Holywell was the site of a major nunnery and Clarkes well was situated just outside the walls of St Mary Clerkenwell, which was founded in 1144 on ten acres of land.30 Fitz Stephen’s reference to the taste of these waters confirms that they were drinking sources. Imbibing ‘holy’ water was part of Christian culture of this period, in which some wells were associated with the cult of the saints and miracle cures, many with pagan origins. The historian Alexandra Walsham describes how the grounds surrounding certain wells ‘became littered with crutches left behind by grateful pilgrims’, who presumably believed that they had been cured.31 External and internal uses of such waters were considered to be equally therapeutic, depending on the ailment.32

Fitz Stephen’s categorisation of the suburban wells as ‘special’ suggests that other un-holy wells related to ordinary water uses such as mere thirst relief or cooking. Within the City walls, the supply of ordinary, but sufficient, high quality, freshwater became a quest in the thirteenth century.

Conducting sweete water

Evidence suggests that the plans to convey water from Tybourne ‘for the profite of the Citty’ began as early as 1236 with donations from ‘Marchant Strangers of Cities beyond the Seas’.33 According to William Fitz Stephen, the City’s increasing populace ‘were forced to seek sweete waters abroad’.34 Significantly in this quote, the water’s quality ranking as ‘sweete’ obviously suggests its relationship to human consumption. The project he was referring to resulted in the construction of the City of London’s first ‘conduit’.

One interpretation of this early form of water engineering, provided by the London water historian H.W. Dickinson, is that the idea for a conduit was inspired by monastic water supplies.35

Tybourne was a village in Middlesex, named after the tributary of the Thames on which it was situated near contemporary Marble Arch, some four and a half miles to the west of London. The ambitious project of transporting water from the Tybourne to the City was not completed until 1285, almost fifty years after the donations had been gathered. Lead pipes, also referred to as ‘rods’, fed the water underground by gravity from the rural west to the urban east. Archaeologists discovered a section of pipe that was destined for the City’s conduit two meters underground, with a diameter of almost ten centimetres.36 Four hundred and eighty-four of these rods were reportedly involved in this ambitious civil engineering enterprise. The early road works must have been quite a labouring and logistical feat (no doubt plenty of medieval travellers were inconvenienced as their thoroughfares were temporarily dug up).37 Eventually, the receiving ‘conduit’ for the water rods was built at the junction of Bucklesbury, Cheapside and Poultry, at the heart of the medieval marketplace for food.38

The water-engineering historian Hugh Barty-King explains that conduits were simply based on the diversion of an existing watercourse and the employment of gravity. Conduit ‘houses’ received the diverted water. They consisted of ‘a large tank of lead or stone into which the water poured itself, and out of which, by a free-flowing spout or a controllable tap, it poured into a stone basin below’.39 Architecturally, conduit houses could be modest or monumental.

Cheapside Conduit was the latter. It was a major new civic landmark, as well as a practical resource. The archaeological discovery of the ‘long rectangular building’ gives us this view of what it consisted of and how the building was used: ‘The vault of this building was still intact and the carved greensand quoins and doorway survived at the eastern end. This led to a staircase which would have exited up to the medieval street. Londoners descended into the building to collect their water before climbing the stairs back to street level.’40 Though there was a practical need to cover the water tank, the scale of the conduit exceeded this function. This excessive mass ensured that the civic and charitable goodwill that had paid for the freshwater bounty could be publicly appreciated.

Did the new water source add to the area’s growth and definition as a market and commercial centre? Clearly the quantity of the water was a motivating factor for channelling water in this way, but there is compelling evidence that the quality of this rural water was perceived to be different, ‘sweete’, and therefore used for specific, dietary-related purposes. John Stow’s seminal early-modern urban study, A Survey of London (1603), includes this record of the Cheapside Conduit’s intended role in medieval water supply: ’…for the poore to drinke, and the rich to dresse their meate’.41 Clearly, the water was considered to be of a dietary quality, though we are left wondering whether the poor drank it only because they could afford no other beverage. One interpretation is that the water was free and publicly available to those on the street, or possibly even to those without a permanent home. However, as we now know, neither the lead leaching from the pipes or the conduit’s building materials were good things for human health.

London grew further in the 1300s, with the population doubling by 1340.42 Perhaps the greater mass of competitors for high quality water was one motivating factor for the Corporation’s installation of a Conduit Warden at Cheapside in 1325.43 Queues for water were likely to be more boisterous than when the Conduits staircase was first used for water seekers forty years previously. There is evidence that the queues were not always socially harmonious. During the 1330s, one group of regular conduit users was criticised because ‘the water aforesaid was now so wasted by brewers, and persons keeping brewhouses, and making malt, that in these modern times it will no longer siffice for the rich and middling, or for the poor, to the common loss of the whole community’.44 The use of water from the conduit to make ale or malt was subsequently banned.

Indoors, medieval Londoners could draw their water from chalk-lined wells within modest houses.45 Coupled with resourceful home-made guttering devices for rainwater harvesting — sometimes causing neighbourly disputes when they flooded adjacent properties — we know that the conduit was not the only water on offer for washing bodies, or clothes, but were these domestic sources considered to be good enough to cook with or drink?46 It is hard to know for certain, but they were definitely more readily accessible than the water from the city centre conduit, which could not serve residents living extramurally. So, the Great Conduit, as Cheapside became known, potentially served a number of practical functions including hydration for those working outdoors, or passing through London temporarily, and a high quality raw material in the centre of food production from a source untouched by urban pollution. The conduit was obviously considered to be successful, or indeed necessary, as the device was replicated elsewhere the following century.

‘A lusty place, a place of all delytys…’47

Just west of Cheapside, lay the other main strip in the medieval City. On Cornhill, the ‘tonne’ was adapted into a cistern in 1401, whilst retaining its penal use on the upper storey of the structure. On top, rogue bakers, nightwalkers and other ‘suspi-cious persons’ could be seen incarcerated in stocks.48 Conduits transcended from functional to festive as state pageants or religious celebrations related to these central features of urban life. During a 1421 pageant, King Henry the Fifth’s wife, Catherine of Valois, was greeted with high theatricality at the little Conduit by ‘giants of a huge stature ingeniously constructed to bow at the right moment, lions which could roll their eyes and…bands of singing girls’.49 The same account also recorded how the conduits flowed with wine instead of water during the pageant.

John Stow, who recorded the rise of conduits before and during his lifetime, reflected on the disappearance of the natural environment under the increasingly built-up City and extramural neighbourhoods. He wrote of the demise of the Walbrooke Stream for instance: ‘This water course hauing diuerse bridges, was afterwards vaulted ouer with bricke, and paued leuell with the Streetes and Lanes where through it passed, and since that also houses have beene builded thereon, so that the course of Walbrooke is now hidden vnder ground, and thereby hardly knowne.’50 As water within London submerged from view, Stow recorded donations for new conduits rising steadily from the late-fifteenth century at the start of the Tudor period and into the Elizabethan period, up until the mid-sixteenth century. Celebrations aside, for many of the City’s workforce and residents, the conduits were associated with the gruelling physical task of transporting water. As the historian Mark Jenner has asserted of early modern London (spanning 1500–1725): ’…for most households the cost of water lay in the hours spent fetching it…’51 Energy and time could be displaced, if a household could afford to pay some other body to expend that labour on its behalf.

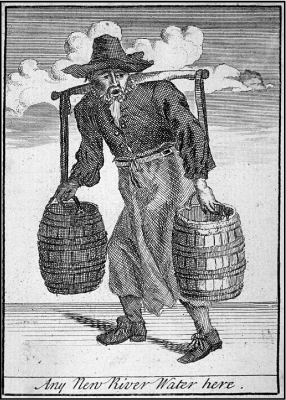

Collecting water from the conduits created an economy and an official workforce of water-bearers, answerable to the City’s Corporation. After 1543, when the City was granted the right ‘to exploit all large springs within a five-mile radius’ to boost conduit resources, the quantity of work for the water bearers was also boosted and their role in urban water collection provided a much-needed employment opportunity for those teetering on the lower rungs of London’s economic ladder.52 A water bearer appeared as a minor character in Ben Johnson’s 1598 play Every Man In His Humour in which he was clearly shown to be of a low social rank.53 Water bearers served wealthy households as dedicated individual servants, or as teams employed by larger companies or institutions. Though water as a raw substance remained free, its transportation to the point of use elicited a charge. Quantity was controlled by the regulated size of tankards that the water bearers had to use. Those standardised tankards bobbing through the Elizabethan street throng, on the shoulders or heads of their carriers, was surely a common sight in early modern London. What exactly the water was used for when it passed from conduit to client is more difficult to ascertain. If the conduits’ bounty did indeed remain ‘sweete and wholesome’ as was intended, then the likelihood of its ingestion is certainly a greater possibility.

We know that people drank at least some pure water in the sixteenth century, because during the Reformation, supping from ‘holy’ wells was banned as a Catholic practice.54 The custom, which had continued from medieval times, became associated with anti-Protestant forms of worship such as idolatry, deifying nature and saints as opposed to one God.55 Waters curative powers were seriously questioned as part of the Reformation’s religious revolution. Then in 1542, this time from a secular perspective, more doubt was cast on water’s valuable properties. Andrew Boorde, the Duke of Norfolk’s physician proclaimed that ‘water is not holsome by it selfe for an Englysheman…water is colde, slow and slake of digestion’.56 Boorde’s health ‘regyment’ also discussed the importance of the use of particular water for dressing meat and baking. He was emphatic that such water must be from a running, rather than a stagnant, source and that for the best results he advised that inferior water should be strained ‘through a thick linen cloth’.57 Boorde seemed to eye the contents of wells with suspicion. Were they stagnant?

By the Elizabethan period, post-Reformation, parish wells had a strong civic function as local domestic water sources and were maintained under the watch of church committees (church vestries became formal governing bodies for parishes from the mid-sixteenth century).58 The well sources were possibly considered to be inferior to ‘rural’ grade water from the conduits, as they was not associated with the labour of water bearers. How preoccupied Londoners were with that quality distinction is difficult to know, though no doubt evidence exists somewhere. Mark Jenner has recorded the switch from well to pump as taking place gradually between the early sixteenth to seventeenth centuries.59 As that low-grade technology evolved, a far more ambitious mode of water supply was also in development.

‘A most artificial forcier’60

Advances in water engineering were moving beyond the conduits’ gravitational system to the use of wheel-based technologies. Now, water could be transported from a lower gradient to the required point of use, particularly when using the new technology in tandem with the natural power of a tidal river.

The engineer Peter Morris was to push the notion of a convenient water supply into completely new territory. Morris, sometimes appearing as Marsh or Maurice in different historical records, had a nationality as uncertain as his surname. Whether he was Dutch, German or English — all of which have been proposed — the land drainage engineer saw an opportunity to exploit new urban water demand with a massive resource that was currently untapped; the Thames. By the 1570s Morris convinced the Corporation of the City to co-invest in a large-scale experimental waterworks scheme to pump from the river at London Bridge. When construction ran behind schedule, officials were reluctant to part with the second half of the finance but luckily for the entrepreneur, he happened to be in the service of the Lord Chancellor, who had a direct line to Queen Elizabeth I. A state hearing of Morris’ predicament, in 1580, concluded that the City Corporation was unfairly withholding monies when the engineer had also personally risked large sums.61 The next year Morris was granted a 500-year lease for the arch under London Bridge where his giant waterwheel was eventually constructed.62

By 1585, water was being pumped from Morris’s wheel-based technology directly into the houses of paying clients; London Bridge Waterworks was in business. It was the first mechanically transported water to enter private houses in the capital. The only limitation of the new convenience was the distance that the waterwheel could propel water, so customers had to be resident in the near vicinity of the Thames, and naturally with sufficient income, to enjoy this luxurious supply. John Stow’s praise for Morris’ enterprise seemed somewhat muted, describing it merely as ‘Thames water conueyed into mens houses by pipes of leade from a most artificial forcier’.63

London’s social stratification of water access had certainly entered a new phase, but what is known of its consumption and use? Though Morris did specify that his machinery was pumping water from the bottom of the river, it is unlikely that the contents of the Thames was considered to be palatable for cooking with or for drinking neat. Also, as he was extracting water from the tidal part of Thames it would have had some measure of salinity. Perhaps his engineers worked with the tides to reduce the salt content? Still, its use for bathing is plausible. Perhaps even a degree of salinity was embraced for that purpose. It could also have been used as a laundry resource, but it is unlikely that river water was consumed as a beverage. Naturally, the river was a dumping ground for all manner of waste and a busy shipping highway but the idea of using it as a source for pressurised piped water had caught on. Bevis Bulmer installed his pumps in 1593 at Broken Wharf, a little further upstream.64 For wealthy householders, pumped water could be used for one set of functions in abundance, whilst water bearers could still be dispatched to fetch superior water from conduits for ‘sweeter’ water needs.

Morris’s civil engineering innovation would become normalised as the convenience and profitability of water’s private supply was demonstrated. The next private water entrepreneur borrowed a bit from Morris and mixed it with a dash of the first conduit philosophy, producing convenient domestic water on tap, but of a purer quality and salt free. Work on the New River’s construction commenced in 1606.65

The New River was a man-made channel conducting water from underground springs in the Hertfordshire countryside north of London to Islington in the expanding suburbs. After many years of development, with funding from City goldsmith Hugh Myddleton, its opening festivities took place in 1613.66 A statue of the entrepreneur still graces the junction of Upper Street and Essex Road in Islington and a Georgian square is named after him. The New River charter protected the water quality, from which no doubt its profitability could be assured: ‘No person to cast into the rover any earth, carrion, nor wash clothes or annoyeth the current, nor convey any sink into the same or lay any pipe to draw off the water, nor dig any ditch, pond, pitt or trench nor plant tress within 5 yards of the river.’67 If these terms were monitored and upheld, one can imagine that the notion of drinking from this pure new water source might have been entertained more readily than the Thames. Piped, corporate supplies’ introduction was followed by more illicit forms of water extraction, which were not appreciated by the London’s community of water bearers.

Quills

Undercover, unsanctioned tapping of pipes feeding the conduits was a form of private water supply that mimicked the premise of the new corporate water, but the big difference was that its users had no bill to pay, or a ‘fine’ as the New River’s charge was called.68 In 1621 the water-bearer ‘brotherhood’ presented a petition to Parliament, protesting that the appropriation of conduit water for private use was affecting their business, because ‘most of the said water is taken, and kept from the said Conduits in London, by many priuate branches and Cockes, cut and taken out of the pipes, which are layed to conuey the same and laid into priuate houses and dwellings, both without and within the City…and many times suffered to runne at waste, to the generall grieuance of all good Citizens’.69 The brotherhood’s frustration was understandable. Some quills tapping the conduit supplies were blatantly illegal, whilst others were sanctioned for the supply of some influential householders, by the Corporation itself.70 Quoting the law governing the management and use of the conduits, the water bearers believed that this private appropriation of public supply contravened the statute book. In particular, they pointed a collective finger at a plumber on the City’s payroll, one Mr Randoll who, ‘out of fifteen branches running into private houses’ had apparently confessed to laying three of them personally.71 It sounded as if some palms may have been well greased to extract such favours. Corrupt water siphoning was not the water bearers only problem. Their ‘broth-erhood’ was also unsettled by the arrival of rogue bearers onto London’s water scene. They claimed that these imposters were serving single institutions, such as Newgate Prison, and therefore unevenly draining the supplies of certain conduits.

Such petty disputes were eclipsed by the devastation caused by the Great Fire of London in 1666, in which 13,200 homes were decimated. Casualties of London’s water infrastructure in the 1666 fire included Peter Morris’s wooden waterwheel and the Great Cheapside Conduit’s structure was also gutted. Like all professions, the water bearers and their dependents — a community of four thousand people in total –must have experienced the effects of the fire’s devastation on London’s social as well as its built fabric. Reconstruction of London Bridge Waterworks soon began and Cheapside was also rebuilt in some form. The illicit practice of quill-laying also resumed. In 1677 Thomas Duncomb swore in an affidavit to the Corporation of the City of London that he did ‘dig a trench in the night time’ to divert a supply from Lamb’s Conduit to a publican’s brewhouse.72

Fresh water seller, ca. 1688. Marcellus Laroon (1653–1702) City of

London, London Metropolitan Archives.

By 1698, some tensions between the conduit and piped water systems were apparent in a petition issued by Cheapside’s residents and water-bearers to the City of London Corporation. The residents claimed that they were in ‘great distress for want of water because several of them have their kitchens two and three pairs of stairs high, which is beyond the power of the New River or Thames Water men to raise their water so high’.73 And the water bearers claimed that if any water was available at the Cheapside Conduit, they could earn a wage and serve the needs of those whom the private water companies were failing. This tension characterised how public and commercial water supplies rubbed against each other in early modern London. Mark Jenner points out how the new water corporations ‘individuated and privatised households, reducing their involvement in the hurlyburly of the public water sources, but they were also the first network technologies, binding thousands of households into a common system’.74

These shifts in the equality of water access in London had a contemporary resonance with the influential political theories of John Locke. In his Second Treatise on Civil Government in 1690, Locke argued that what had been produced by the ‘spontaneous hand of nature’ was altered when it was mixed with labour.75 As he elaborated: ’…though the water running in the fountain be every one’s, yet who can doubt that in the pitcher is his only who drew it out? His labour hath taken out of the hands of Nature where it was common.’76 Certainly evidence suggests that the conduits’ contents were prized on the basis of a quality cooking and drinking product, so in their case labour mixed with the value of a particular grade of water. Maintaining the infrastructure that assured the continual flow of high quality water contributed to its cost as a civic water source.

Cordial and Healthful Waters

From a drinking water perspective specifically, by the end of the seventeenth century an elite commodity entered English culture. The social historian Phyllis Hembry charts how the fashion for hot mineral water bathing enjoyed by Elizabeth I, escalated into the health-related Grand Tour. This activity grew in popularity amongst the gentry between 1585 and 1659. As the historian Alexandra Walsham has argued, the Reformation’s suppression of the association between water and healing did not last for long and both the church and the state participated in the culture of reviving a therapeutic water culture.77 Endorsed by medical men for internal as well as external physical benefits, drinking spa water became a fashionable, healthy habit. Back in England, Hembry explains how in the early sixteenth century a ‘shortage of places for bathing led to a movement for drinking cold mineral water’.78 Bath’s famous Pump Room, for instance, started trading drinking water cures in 1706, though its water was thermal.79 Bottled, English spa waters soon emerged as a new product that could be supped remotely from the spa.

London’s coffee houses, well established as centres for social and political discourse by the early eighteenth century, presented themselves as ideal shop fronts for purveyors of bottled water. A roaring trade in both English and Continental spa waters was in motion by the 1730s.80 Hembry’s research mapped London as the centre of bottled water demand. A dozen bottles of mineral water from Bath could be purchased for 7s.6d. (approximately £30, or £2.50 a bottle in modern currency).81 This new market was clearly highly profitable, so it is not surprising that many miraculously healthy springs were ‘discovered’ around London later in the century by wily entrepreneurs. Public ownership of natural water sources was fast becoming a quaint old idea.

A whole host of popular entertainment developed around London’s own ‘spas’, for which season tickets could be purchased.82 Spring water could be enjoyed at the spas themselves but products such as the Hampstead Flask ensured that healthy waters could also be enjoyed remotely from the spas for thruppence (or about £1 today).83 As Georgian culture segued into the aesthetics of the Regency period, spas morphed into ‘pleasure gardens’. Though water drinking was the rasion d’être of these leisurely places, they were by no means alcohol free. Drinking water alone would not have occasioned such festivities for which the London ‘Spaws’ became renowned. New tastes in alcohol were also being explored.

Eliza Smith’s renowned cookbook The Compleat Housewife, first published in 1729, contained a panoply of recipes involved, or based on, water. The growth in the popularity of distillation meant that a whole host of ‘cordial’ waters could be brewed at home. Smith listed recipes galore to cure all manner of ailments, including giddiness of the head and revival from near-death. Her medicinal recipes’ ingredients reveal their high alcohol content. Smith’s instructions for brewing ‘lemon wine’, which could pass for ‘citron water’ if a disguise was required, included a generous two quarts of brandy.84 ‘Plague water’ was also infused with a gallon of white wine. As homemade medicines, which were commonly administered by women in the seventeenth and, well into, the eighteenth century,85 some of the cordial waters were intended as cures for serious maladies such as breast cancer, or to aid labour during stillbirths.86 Despite the amount of alcohol in the concoctions, Smith specified that spring water should be used as a base. Her specification fitted with the fashion for taking mineral water as a healthy remedy and shows how drinking water’s value as a commodity was increasingly tied to its provenance. Spring water consumption by the gentle-womanly and middle class readers of The Compleat Housewife was part and parcel of the material comfort their classes enjoyed, but it sounds like a small bottle could have gone a long way. The apparently refined use of distillation, however, was not a practice enjoyed by all Londoners.

‘Gin mania‘, as the social historian John Burnett calls it, gripped London from 1720–51. As he writes: ‘The immediate causes of the epidemic were the ease of manufacture by hundreds of small distillers, the low duty of 2d. a gallon, and the absence of any requirement for a retail licence. In 1725 there were a reported 6,187 premises selling spirits in London, excluding the City and Southwark, and in Westminster and St Giles one in every four houses were said to be dram shops.’87 The inner city neighbourhood of St Giles was portrayed by William Hogarth in Gin Lane (1751), as part of a campaign against the spirit’s negative social consequences. His engraving famously depicts the debauchery unleashed by the cheap liquor on London’s poorer inhabitants. In Hogarth’s engraving a mother is shown nodding off with a dreamy, drunken smile on her face, as her baby is falling to the ground from her breast. Other details in the image depict financial ruin-by-gin and death-by-gin, whilst the pawnbroker and undertaker profit.88

That decade was also significant in terms of less toxic drinking issues. Medical historian Anne Hardy highlights 1756 as a pivotal year in her pioneering study of London’s relationship between water and public health in the eighteenth century.89 In this year, the medical doctor Charles Lucas’ Essays on Waters was published. Lucas retaliated against prevailing water snobbery by studying, as he explained ‘medicinal quality and uses of simple waters’.90 Mineral water profiteers cannot have been pleased with this attempt to endow un-bottled water with equally medicinal virtues. The physician examined London’s water as part of his project.

Though Charles Lucas siphoned murky water from the Thames, its appearance did not equate with contamination in his eighteenth century eyes. Apparently it was still acceptable in this state for ‘drinking or bathing…for dressing of food…making malt and for brewing, for preparing medicines’.91 Anne Hardy notes that, for this physician, the solid content in the water samples he drew from the river, ponds, pumps and springs — all sources that Londoners were consuming from –was not perceived to present any danger to health. Significantly, the other 1756 event Hardy points to was a publication by another physician warning of ‘drinking beer brewed with well water’.92 Whether it was purported to be good or bad for health, water’s drinking quality seemed to be under a new level of scrutiny, in medical-scientific circles at least.

The next significant event in Hardy’s account was in the 1790s, when she argues that the emergence of New Chemistry propelled quality analysis forward. New Chemistry was propelled forward by the research of Antoine Lavoisier in France, who reduced chemical substances into a simpler set of elements in a forerunner of the periodic table. Through his experiments, he showed that air could be further defined as oxygen and that water a compound of hydrogen and oxygen.93 This focus on substances’ minutiae brought attention to water’s organic contents. Was this a source of impurity? Hardy asserts that such thoughts permeated beyond medical and scientific circles, for example to the architect James Peacock. Peacock patented the theory and hardware for a water filtration system in 1791.94 His invention pre-dated any use of large-scale filtration technology. In 1793, the designer self-published A Short Account of a New Method of Filtration by Ascent. Peacock’s aim was to produce a soft water that was not turbid, on the grounds that it was healthier for human consumption than hard water: ‘Many are sensible of the indelicacies of turbid soft water; and are thence driven to the use of hard water, although they are not apprized of the probable danger to their health, from the petrifying quality, or from the metallic, or other mineral taints too frequently suspended and concealed therein.’95 It was certainly an alternative position from the wonders of minerals that the bottlers of spa waters were glorifying. ‘Indelicacies’, however, were not quite diseases.

James Peacock was promoting his filtration cistern as a domestic product: ‘This little apparatus will yield an ample sufficiency of perfectly clear soft water for every necessary use of a small family, of six to eight persons.’96 The architect envisaged transforming the quality of water in homes by capturing the supply as it entered the service pipe. Peacock’s cistern was an elite product intended for those residences that were already plugged into the corporate water network, rather than one designed for water fetched from the parish pump to be poured into. The invention did not make the architect a household name but his notion of filtering water was truly ahead of his time. Sadly for Peacock, he would have enjoyed a more lucrative career a few decades later.

Such technological entrepreneurship in last decade of the eighteenth century was consistent with the age of the industrial revolution that was transforming Britain’s economic and social fabric. The growth of cities to fuel the labour for this industrialised society and to transport its products abroad would mean a new demand for water and sanitation facilities.

Consequences for water quality soon became apparent as nineteenth-century London swelled along the banks of the Thames.