Private Water and Public Health 1800–1858

And so suspicious had several of the great metropolitan brewers become of Thames water that they had been forced, at vast expense, to look to wells for their supplies. 1 (Pollution and Control, Bill Luckin)

The brewers’ unease with polluted Thames water described by the historian Bill Luckin marked the specific shift in public attitude towards the river that occurred in the 1820s. It was in that decade that the sharp decline in the river’s stock of fish also had an impact on the fishing economy in central London.2 The culprit was obvious. A prohibition on household drainage connection to public sewers flowing straight into the Thames had been lifted in 1815.3 Unfortunately, this coincided with the rise in purchases of the flush water closet and improved water supplies to these facilities, at least for those who could afford both luxuries.

Prior to the 1820s, as James Graham Leigh comments in his account of London’s water companies’ machinations, ‘water quality does not seem to have been considered so important’.4 Population growth precipitated a rising demand for water for domestic and industrial uses. More labouring Londoners meant more call for refreshing beers and, consequently, that all-essential raw material. Between 1801, the year of Britain’s first census, and 1821, central London’s population rose from 959,310 to 1,379,543. A further 200,000 people were counted in Greater London.5 Industrial revolution and imperial growth, such as the Act of Union with Ireland in 1800, created a new flow of migrant labour into the capital to boost productivity.6 Many people continued to rely on the public resource of the parish pump, but as the century progressed, piped water, even if only to shared communal sources became a standard of modern London life. This chapter explores how notions of water quantity and water quality became contested as Britain’s public health movement emerged.

Before 1806, four private companies served piped water to wealthy households, at least those without the convenience of private wells.7 London Bridge Water Works and the New River companies were still going strong. Also serving homes and businesses north of the river, York Buildings Water Works started pumping supplies at the end of the seventeenth century, followed by the Chelsea Water Works Company in 1723.8 Early in the nineteenth century competitors to those established water providers surfaced in London’s water supply market. West Middlesex Water Works began pumping to homes in the affluent neighbourhoods of Hammersmith, Kensington, Marylebone and Paddington in 1806, whilst in 1807 the East London Water Works Company set its sights on serving the hydration needs of the less well-off side of the city by exploiting the natural resource of London’s other river; the Lee.9 Then, in 1811, the Grand Junction Company promised to supply water of a superior quality from the rivers Colne and Brent to consumers in Oxford Street and Drury Lane.10 Suburban companies included the Hampstead Water Company, the Shadwell Water Works and, on the south side of the river, the Lambeth Water Works and Borough Water Works.

Areas of supply were ungoverned and unregulated. Consequently, company pipes overlapped in neighbourhoods and those enterprises competed for neighbouring customers. This unsustainable system did not last for long. Between 1815 and 1818, the water companies hammered out agreements to carve London into water supply monopolies. Some corporations did not survive those negotiations.11 The companies left standing had extraordinary power. As water rates rose steeply in some areas rose following monopolisation, many educated residents were disgruntled.

Anti-Water Monopoly Association

Historians of nineteenth-century water consumerism, Frank Trentmann and Vanessa Taylor point to the mobilisation of residents in ‘affluent St Marylebone’ under the banner of the Anti-Water Monopoly Association in 1819 as an important, if brief, period of consumer activism. This episode shaped the future of London’s public water discussions by igniting ‘debate about the rights of householders’ of London’s middle classes.12 The minutes of the Anti-Water Monopoly Association’s inaugural meeting state that its purpose was ‘mutual protection against the arbitrary and oppressive proceedings’ of the West Middlesex and Grand Junction water companies.13 Petitioning about ‘supply of this first necessity of life’14 gained sufficient momentum for a parliamentary select committee enquiry in 1821, however it resolved that the companies’ prices were fair.15

We cannot say that this water debate was specific to drinking water; however the description of water as a ‘first necessity’ suggests its role in biology and basic health, along with other uses. Flushing toilets had been entering the homes of the wealthy in larger numbers alongside piped water supplies, however the removal of human waste with water rather than the earth was still a nascent idea, because a waterborne sewage system did not exist.16 Also, what might have been meant by good quality water at that pre-microbiological point is difficult to discern.

Perceptions of consuming water as a lone substance can be tricky to trace, particularly in terms of its use across the social strata, but the use of mineral water as a medicine was certainly still in vogue in the second decade of the nineteenth century. Mr Lambes Mineral Water Warehouse on fashionable New Bond Street was brimming with competing products, and he had been in business since 1799. One advert prescribing the use of Aluminious Chalybeate Water hints at contemporary thinking about drinking water quality: ‘The patient is to begin with one ounce of water, diluted with two ounces of pure rain water.’17 Specifying the use of rainwater for the ill certainly cast a shadow of doubt over the perceived health merits other sources, such as piped water. Late in the 1820s, any latent doubts Londoners generally might have about whether their water was good, bad or indifferent were awakened when an incendiary pamphlet was published.

The Dolphin ¦ Monster Soup

John Wright claimed that Mr Robson, a former director of the Grand Junction Water Company, had confided in him in 1826 that the source of the company’s supply was not from ‘the streams of the vale of Ruislip’ as its customers had been led to believe.18 Robson led Wright to the point at the Thames where the Grand Junction was extracting its domestic supply and urged him to expose the company’s corruption in his capacity as a writer and publisher. Wright’s polemical pamphlet, The Dolphin, or Grand Junction Nuisance was published in March 1827, just a couple of months after Robson’s death.

The pamphlet’s title was a reference to the decorative opening of the Grand Junction Water Company’s intake pipe in the Thames. An illustration accompanying the booklet showed the proximity of that pipe to the outfall of sewers. Wright condemned the private water monopolies as an ‘unholy alliance’ and the Grand Junction Water Company in particular for distributing ‘a necessary of life, so loaded with all sorts of impurities, as to be offensive to the sight, disgusting to the imagination, and destructive to health’.19 Though he was unaware of the precise impact of sewage on drinking water, Wright instinctively knew it was not a good practice for excrement and drinking water to mingle. The author viewed the Company as particularly corrupt because of its misleading adverts to supply ‘pure and excellent soft water’, when the source was evidently not as pure as the New River’s fairly priced and ‘wholesome’ water.20 Wright dramatically exclaimed: ‘The very sight of a glass of Grand Dolphin water serves as an excuse for a glass of spirits, to qualify the effects it may have on the stomach.’21 He also pointed out the capital’s water supply inequalities, on the basis that members of the nobility and gentry had private wells attached to their mansions.

The pamphlet’s dissemination led to a ‘numerously attended’ meeting of ‘respectable’, presumably concerned, people.22 Sir Frances Burdett raised the water quality exposé in Parliament and soon a Commission for Inquiry into the Supply of Water was launched to examine the truth of Wright’s claims.23

Throughout January 1828 The Times published extracts from a document that Wright had furnished the Inquiry with as a supplement to The Dolphin pamphlet. The serial was entitled The Water Question. This phrase would become synonymous with public and political discourse surrounding London’s water until the end of the nineteenth century.

In the first edition of The Water Question, Wright records his pleasure that the Dolphin pipe intake ‘in the Thames at the foot of Chelsea Hospital…is now almost as well known and as much pointed at, by passengers going up and down the river as the Royal Hospital itself’.24 He also declared that customers should have been informed about the new point of extraction and supplied with an analysis of the water. His latter point raised the important question of how quality was measured, and by whom?

Passionate as he was about his water pollution position, Wright had no scientific acumen to offer. In the next instalment of The Water Question, he claimed: ‘The impurity of the water, which so greatly injured the health of inhabitants, arose, not from particles of matter floating in the fluid, but from the quantities of matter held in chymical solution‘, adding that ‘no filtration could remove this species of impurity.’25 Unlike the eighteenth century water-testing doctor we met in chapter one, Charles Lucas, Wright saw matter in water as ‘impure’. Evidence was needed to back up this position.

Chemists were to become critical figures in the water quality and treatment debate, though the science was still an occupation populated by amateurs.26 Wright pronounced that one chemist, Dr Paris, agreed that filtration was pointless, however other experts did not concur. Those chemists who publicly defended the filtration solution in the scientific press were, in Wright’s mind, trying to extinguish the validity of the government Inquiry. Wright’s rhetoric reached fever pitch over this ‘doctored’, that is filtered, water.27 For him, consuming filtered water, which masked impurities, might make the English a filthy race and a mockery of the cleanliness-is-next-to-godliness maxim.

Grotesque imaginings of the Thames’ contents in this public debate was an irresistible subject for the leading caricaturist of the period, William Heath, or Paul Pry (his pseudonym). Published in 1828, Heath’s Monster Soup presented Wright’s claims with equal doses of humour and horror. The etching’s publisher, Thomas McLean, issued daily caricatures of popular political subjects, so it is likely that the image was widely circulated, for instance in coffee or teahouses, or perhaps even the public house, where beer consumers may have been keen to scrutinise the raw materials of their pints more closely.28 Those who were passed a copy of Monster Soup might well have dropped their cup or glass, like the caricature’s human subject. Hydras; gorgons and chimeras with razor-like teeth, over-sized eyes, spines and pincers presented an unsettling view of the teeming inhabitants of London’s main water source. Of course, it was satire, but was it exaggeration or merely magnification?

A contemporary archivist noticed the caricaturist’s final stroke of humour: ‘The P.P. of the signature raises his hat to a tiny pump, saying, Glad to see you hope to meet you in every Parish through London.’ 29 This footnote might well have indicated that Heath, and others, thought pump water to be a safer bet than piped water. That view certainly tallies with Dr Charles Lucas’ analysis of London’s water sources back in 1756: ‘Well or pump water approaches nearest of that of springs or fountanes.’30 Despite the time lapse between these two pieces of evidence, it certainly points to a differentiation between water sources and therefore drinking water quality made by, at least some of, London’s citizens.

Monster Soup, commonly called Thames Water, 1828. William Heath

(1795–1840) Wellcome Library, London.

Monster Filter

In 1829 Chelsea Waterworks responded to the water confidence crisis by dismissing Wright’s negative position on filtration and employed a filtering system invented by James Simpson to treat its supply.31 We can consider this move to capture the minute or invisible contents of London’s raw water as the first step towards modern, industrial water treatment.

John Wright’s critique of London water suppliers alluded to the connection between drinking water and disease, mooted in some medical circles. For instance, he referred to a doctor’s report about army troops contracting dysentery as result of their drinking water supply.32 His question about disease striking London in the context of the water quality inquiry was prescient: ‘Although this enormous metropolis may at the present moment be, generally speaking, in a healthy condition, does it therefore follow that it will always remain so?’33 It was not long before his question was answered. Cholera morbus, also known as malignant diarrhoea, was a disease that had been previously associated only with ‘natives’ in the east.34 Cholera’s geography changed in 1832.

Caused by the Vibrio Cholerae bacterium, cholera’s symptoms were the same then as they are now in countries with poor sanitation or sewage-contaminated water supplies: Severe diarrhoea, followed by rapid dehydration, the malfunctioning of vital organs and then death within days, if untreated.35 William Marsden, a surgeon at the Free Hospital, founded as a result of the 1832 cholera outbreak, wrote of reactions to the disease’s arrival: ‘On the first appearance of this unknown disease in London, medical men of every grade, more particularly those in the higher walks of the profession, on viewing the afflicted patient, became terrified and panic-struck; and the public, in consequence of their professional advisers being ignorant of the nature of this malady, were completely bewildered and paralysed…the richly-endowed hospitals of this Metropolis closed their doors against the wretched sufferers, the affluent inhabitants fled, and the great wealthy members of the faculty dared not, or would not, condescend to visit the habitation of the afflicted.’36 The Free Hospital provided an open door to those who contracted cholera, in an act that was equally humanitarian and medically pioneering because treatments for cholera were still entirely experimental.

Marsden and his colleagues used a saline solution treatment, which involved copious rehydration with water before patients ingested the salty fluid.37 Presumably the Grand Junction Company’s supply was not being used if they were to have any success. Records of the hospital’s patients list those treated with the saline therapy as seventy-seven in total. These patients were all discharged. The Free Hospital’s experiment was stunningly important, as cholera’s treatment today is still the oral administration of water and salts.

From the scant coverage of the epidemic in The Times, it is clear that the disease was confined, at that point, to the ‘poor, the wretched, the dissipated, and the destitute’, as Marsden collectively referred to the victims.38 The hospital’s work certainly made no headlines. However, the subject was deemed worthy of attention by the satirist George Cruikshank. His 1832 illustration of the Water-King of Southwark represented Londoners decrying the condition of the Thames, as the source of their piped water. Crowds gather on the banks, with a chorus exclaiming: ‘Give us clean water!’, ‘Give us pure water!’, ‘We shall all have the cholera.’39 Cruikshank’s representation of a politically vocal public, probably of middle class economic status, was common for satirists at that time and clearly cholera was a current issue. Also in 1832, the first of Britain’s parliamentary Reform Acts was passed, widening the electorate to include all (male) property owners. Instinct told Cruikshank, and the public he was representing, that the condition of Thames and the outbreak of cholera was no coincidence. Connecting a particular water company with the disease suggested a relationship between the fatalities from cholera and the geography of the private water supply. Chelsea Waterworks, with its grand new filter, for example, was not satirised.

On her Promenades Dans Londres the radical French socialist Flora Tristan noted Chelsea’s ‘monster filter’, designed to produce ‘clear’ water, as she termed it, for Londoners.40 She critically observed that good quality water was not available to all citizens. In her London Journal, Flora Tristan recorded a lack of ‘sumptuous and monumental fountains’ like Paris but described the alternative: ‘…one does encounter iron pumps in many streets. An iron chain is affixed to the post with a dipper…This dipper is the economical goblet offered to the pauper by his lord and master, the rich man.’41 From Tristan’s interaction with London’s wealthy inhabitants, she gathered that they were not in the habit of water drinking from the pumps. She quoted the following, possibly from an anonymous source but more likely as a shorthand for their general view: ‘“…here water costs the people nothing, they may drink at their convenience without going to draw water from the river”’.42 One gets the impression that what she really felt about the inequity of London’s segregated water supply was not uttered in polite conversation: ‘In a country where scarcely one person in twenty-five can drink wine, and one in seven drink beer, is it not ironically insulting to offer the people of London water which has been dirtied by all the drains in the city?’43

Flora Tristan’s account of 1830s London generally documented some of the living conditions that would preoccupy Britain’s public health movement. As she wrote about St Giles Parish, which was hidden from the view of genteel eyes down an alleyway off Oxford Street: ‘In St Giles one feels asphyxiated by the stench; there is no air to breathe nor daylight to find one’s way. The wretched inhabitants must wash their own rags, and they hang them out to dry on poles that stretch from one side of the alley to the other, so that fresh air and sunlight are completely blocked out.’44 Tristan’s visceral account of the ghetto, a place that became increasingly associated with Irish immigrants post-famine, was consistent with the descriptions of urban squalor that the social researcher Edwin Chadwick would horrify, and entertain, middle and upper class readers with in his 1842 book The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain.

Edwin Chadwick’s role in Britain’s public health movement is extremely well documented therefore this account only briefly references how his concerns bore on the drinking water debate. Firstly, Chadwick was highly critical of the ‘capitalists’ who sold water in London.45 He believed that water provision should be a municipal affair to improve drainage and support the ‘promotion of civic, household and personal cleanliness’.46 Improving standards of hygiene was closely connected in the sanitary reformer’s mind with improving standards of morality. Chadwick argued that an abundant water supply was the answer to disease amongst the ‘labouring population’. His gaze on water was trained on the quantity needed to wash ones body and home, and drain ‘filth’ away, rather than a concern about the quality of water that might be ingested for drinking or cooking. Legislation soon followed his unsanitary account.

1844’s Metropolitan Buildings Act concurred with the Chadwickian drainage position. All new buildings were to have improved, covered drainage systems but, problematically, waste from properties with water closets was to be drained into the Common Sewer.47 This drainage legislation preceded an effective sewage system. That issue was not considered more deeply until the members of a Royal Commission met in 1847 to discuss how the health of London’s inhabitants might be improved. The same year, the national Towns Improvement Clauses Act was passed, with a clause that would be detrimental to river water. Under its terms, the new Metropolitan Commissioners of Sewers was empowered to ensure that the ‘effectual draining’ of London was carried out.48 To achieve that end, these Commissioners were free to enforce the connection of sewers ‘to communicate with and empty themselves into the Sea or any public River…’.49 Whilst a full scheme for achieving that effectual draining was being planned, the move positively encouraged even more raw sewage to flow into the Lee and Thames. It only added to the problem of water closets becoming ever more normal features of middle class London homes. The engineers’ task was unenviable and the scale of what had to done and how it could effectively be achieved, would not be resolved overnight. Cholera erupted again in 1849.

In the City of London alone, more than eight hundred people died from the bacterium’s violent assault between June and October.50 The Free Hospital’s treatment method was clearly not in use by the doctors who saw these patients, if they received any treatment at all. One reason for this disconnect between 1832 and 1849 was the rise of an idea from the Chadwickian school of public health.

Miasma theory proposed that fatal diseases such as cholera were being transmitted via the air. This belief laid the blame for disease firmly on the doorsteps of the poor. Their dirty environments were producing the filth that was mobilising in air and infecting not just them, but now other classes too. Only one person ventured to posit a different argument during the 1849 cholera outbreak. This doctor was convinced that cholera was being transmitted via drinking water. His name was John Snow.

Though John Snow’s evidence supporting his theory of cholera’s waterborne transmission was still accruing in 1849, he was moved to publish his work-in-progress, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera immediately after the epidemic. He dismissed the ‘miasmists’ because their view that cholera could be ‘inhaled and absorbed by the blood passing through the lungs’ necessitated a predisposition for ‘a great number to breathe it without injury’.51 To Snow, this was not plausible because cholera’s symptoms did not manifest in the manner of other blood poisoning diseases. He believed the symptoms pointed to its transmission in the alimentary canal and he suspected the disease’s form was related to ‘the continuity of molecular changes, by which combustion, putrefecation, fermentation, and the various processes in organised beings, are kept up’.52 His interpretation sounded distinctly microbiological, even though that realm of knowledge was in its infancy. This first published thesis about cholera was drawn from fresh evidence of the 1849 epidemic. Snow believed that it followed the pattern of 1832’s outbreak, in which he saw a connection between company water serving east and south London that was drawn from the sewage-contaminated river. Two neighbourhoods where cholera levels were curiously inconsistent in their spread featured in his pamphlet.

The first neighbourhood was a poor community. Thomas Street in Southwark lay opposite the Tower of London, where two courts of modest housing lay adjacent to each other. As Snow wrote: ‘Now in Surrey Buildings the cholera has committed fearful devastation, whilst in the adjoining court there has been but one fatal case.’53 The only difference that Mr Grant, the assistant surveyor of the Commissioners of Sewers noticed in his report, studied by Snow, was that in the courtyard of Surrey Buildings ‘the slops of dirty water poured down by the inhabitants into a channel in front of the houses got into the well from which they obtained their water’.54 The neighbouring courtyards did not share the water source, but clearly the cheek-by-jowl conditions suggested the air quality shared between the residents was the same. Snow’s second case, significantly, introduced a neighbourhood that would not have been deemed unsanitary by Chadwickian standards into the equation.

Albion Terrace in Wandsworth, as described by John Snow, consisted of ‘genteel suburban dwellings of a number of trades-people’.55 The community’s twenty fatal cases of cholera were blamed, by Snow, on the contamination of a shared water tank by a leaking cesspool which the surveyor Mr Grant found when the ground was opened up. In fact, Snow wrote that the victims themselves ‘attributed their illness to the water’, noticing it was impure but consuming it anyway; obviously without the knowledge that it could be fatal.56 The doctor explained how secondary infection could spread via hands and food once the cholera ‘evacuations’ had contaminated anything that might be subsequently ingested. He countered Dr Milroy’s report to the General Board of Health that Albion Terrace’s mortality was caused by an open sewer in Battersea Fields transmitting cholera into the air, by pointing out that the houses surrounding the exclusive water supply of the affected houses, were ‘quite free’ from cholera.57 Snow concluded in his pamphlet by a persuasive argument that his theory was more optimistic: ‘What is so dismal as the idea of some invisible agent pervading the atmosphere, and spreading over the world?‘58 He proposed that, ‘if the writer’s opinion be correct, cholera might be checked and kept at bay by simple measure that would not interfere with social or commercial intercourse…’59 Despite Snow’s pragmatic stance, the miasmists were firmly attached to their pessimistic worldview. When cholera vanished again, Chadwick and his colleagues may well have agreed that a storm had simply cleansed the air.

Water became more politicised in London as a result of the epidemic. Educated professional citizens and official sanitary reformers alike sheltered under the umbrella of the Metropolitan Parochial Water Supply Association in 1850. Its concern, liker the Anti-Water Monopoly Association before it, was the control of water by private corporations, rather than the quality of the supply. Publicly controlled water and ‘a constant supply at high pressure’ was the Association’s goal.60 But in London’s scientific community, others were convinced by John Snow’s thesis and were consequently preoccupied with the finer constituents of water.

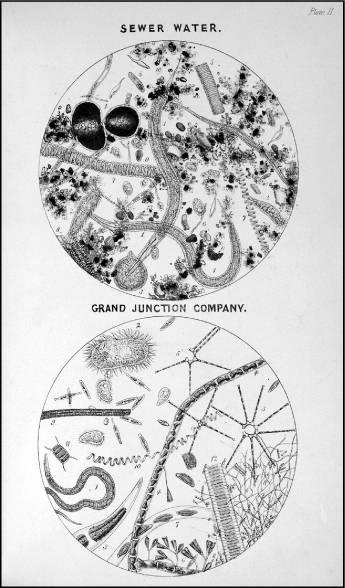

One result of the waterborne movement was that microscopist Arthur Hill-Hassall examined London’s corporate water supplies, publishing the results of his study in 1850. He qualified that his experiment was needed because of the public focus on the ‘defective condition of the water supply of London’.61 The physician-cum-microscopist was dissatisfied that the only information chemists produced about organic matter referred to ‘traces’. What were traces? Like Snow, he thought there was more to the science of water analysis: ‘It will become apparent that these traces…are complex in organisation, endowed with life and in many cases possessed of active powers of locomotion.’62 Also referring to these microscopic inhabitants of London’s water supply under their popular title, ‘animalcules’, Hill-Hassall admitted that nobody knew what they were.

Sewer water and Grand Junction Company, Plate 1

A microscopic examination of the water supplied to the inhabitants of London and the suburban districts, Arthur Hill-Hassall (London: Samuel Highley, 1850) Wellcome Library, London.

Christopher Hamlin, a historian of nineteenth-century water analysis, pinpointed that the importance of Hill-Hassall’s book ‘was to make microscopic life a new category of impurity, and a great deal of debate in 1851 and 1852 was concerned with what exactly such creatures signified’.63 At this point chemists and microscopists were competing in the water analysis sphere, but neither knew how to conclusively explain the significance of the revelations produced under the lenses of their microscopes.

Hill-Hassall’s lurid microscopic drawings were presented to Parliament, possibly during the 1851 Metropolis Water Supply Bill’s debate when there was much discussion of animalcules.64 Whether the politicians involved were of the Chadwickian or Snowian schools of thought, the state of London’s water was equally problematic. Much of the debate revolved around the provision of more water to purify the slums, or ‘disgusting dens’ according to one speaker in the House of Commons. Water’s cost was also noted: ‘Nine different companies distribute water into the houses at exaggerated rates, and the poor people who cannot meet the demands of the companies are often obliged to drink the hard disagreeable water of the wells.’65 For that speaker, the well water was still not perceived to be unhealthy per se but he was clearly indicating that piped, softer water was more palatable. Quality was important to other debaters. Mr Moffat referred to evidence in the Board of Health’s reports which claimed that ‘the quality of the water was very objectionable and unwholesome, and that organic and vegetable matter was found in it of a highly prejudicial character’.66

Beyond the House of Commons’ debating chamber, many an M.P. may have been enjoying a premium glass of drinking water at the Great Exhibition during the summer of 1851. The Exhibition was the social event of that year. Over six million people attended, many travelling by train from outside London and internationally. Covering twenty-six acres of Hyde Park a monumental glass structure, known as the Crystal Palace, was designed by the architect Joseph Paxton to showcase the wares of more than one thousand exhibitors from every nook and cranny of the British Empire. At this Great Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations, the burgeoning fashion for teetotalism was reflected in the catering specification: ‘The contractor at each area must supply fresh filtered water in glasses gratis to visitors, and keep a sufficient supply at each area…no wines, spirits, beer or intoxicating drinks can be sold or admitted by the contractor.’67 Schweppes was awarded the contract to keep the refreshment rooms supplied with this free water, though its origin was not described. Those who wanted to pay for their water at Schweppes’ concession could opt for soda water, an innovation made possible by the company’s development of carbonation and the mass production of fizzy soft drinks.68 A live soda-water aeration performance by one Mr Cox was also reported to be pulling in the Exhibition’s crowds, possibly because he gave away free samples.69 A water purification outfit also exhibited its wares.70 Teetotalism, otherwise known as temperance, was also present in a guerrilla stunt at the Great Exhibition’s centrepiece, the Crystal Fountain, where a mass of teetotallers ‘thronged from all parts of England into the metropolis in the pursuance of a half business-like, half-festive “temperance demonstration” ’.71 The demonstrators ritualistic surrounding of the Crystal Fountain — though it was a decorative rather than a drinking fountain — offers a curious insight into water’s symbolic potency as public health was becoming increasingly tied to social reform. From a practical perspective, more teetotallers meant a greater demand for quality-assured drinking water.

Back at the House of Commons’ debate about the Metropolis Water Bill, a statement by Sir W. Clay drove to the heart of the issue: ‘The only question for the House was, what conditions they ought to impose on those to whom the supply of water was entrusted?’72 In the legislation that followed, London’s corporate water supplies were regulated for the first time and public health principles became legally tied to the supply of urban water. Following the vigorous exchanges of medical, public health and political opinions about water during the debate, the Metropolis Water Supply Act became law in 1852. By 1855, companies would be required to ‘effectually’ filter their water, transport it in covered aqueducts or pipes and provide a constant supply.73 From a quality perspective, the most significant clause picked up on the argument of Joseph Wright, that the point of abstraction in the Thames was critical: ‘No water company after August 31, 1855, should take its supply from the Thames below Teddington Lock.’74 This point on the river, in west London, was where it ceased to be tidal and therefore where, upstream, the water was entirely free from salt.

A competitor to the water companies’ river-derived source, the London (Watford) Spring Water Company promptly saw an opportunity to cash in on public concern about animalcules. The company employed two leading microscopists to dip their test tubes in the Thames above Teddington Lock and analyse the results. They reported that it was ‘a water much contaminated with organic matter…one of the last sources to which the Metropolis should look for a supply of pure water’.75 Watford Spring’s contents, on the other hand, were found to ‘be free from organic matter as any water can be in its natural state’, conveniently for those on the water company’s payroll.76 But before the new abstraction and effectual filtration systems were in place, cholera broke out again in 1854.

This time cholera struck in the heart of John Snow’s own cosmopolitan, central London neighbourhood of Soho. In the course of ten days between August and September 1854, cholera bacteria multiplied wildly within a short radius of a water-pump at the junction of Broad Street and Cambridge Street. Snow’s claims, in conjunction with the fieldwork of Reverend Whitehead, about the pump’s role in dispensing the disease convinced the local vestry to have the handle of the pump removed on the 8th September.77 Snow’s famous cholera map was based on the lives that the epidemic claimed in relation to that Broad Street pump.

His insights into the consuming habits of Soho’s residents prove that, despite water’s bad press, earlier in the century, its consumption was a widespread practice in daily life. However, as Snow himself reflected about consumption habits: ‘The English people, as a general rule, do not drink much unboiled water, except in warm weather.’78 The outbreak occurred at the height of summer during this outbreak and the range of people ingesting the Broad Street pump’s water cold was clearly recorded by John Snow as he mapped the pattern of consumption and cholera contraction. It was consumed in a local coffee house at dinnertime, as a mixer for shops selling sherbet, or to dilute quick nips of brandy or other spirits in nearby pubs.79 That pump’s water quenched the thirst of workers in local percussion-cap and dentistry material manufactories, but plain water consumption was not confined to those who, economically at least, had no other choice.80 It was enjoyed by an army officer dining in Wardour Street and an ‘eminent ornithologist’ who lived on Broad Street, though he decided against drinking it after noticing the offensive smell around its vicinity on 2nd September.81 An ex-Soho resident living in Hampstead was even brought a bottle from the pump by her visitors, as she apparently preferred its taste to her local supply.82 Snow’s record of these consumer habits shows the centrality of the pump to neighbourhood life, despite the availability of piped water. This suggests at least two things. One is that the pump was reliable for a fresh supply given the intermittent nature of the corporate water. Or that the underground supplies were perceived to be more drinkable and tasted noticeably different to river-derived water. The popularity of the pump is mirrored by a detail in 1828’s Monster Soup caricature in which the stick figure of Paul Pry, who we have already met, doffs his cap to a parish pump.

There is little doubt that some Londoners preferred pumped to piped water. Still, Snow’s second tranche of evidence about 1854 also shows that drinking piped company water was habitual. Either way, water drinking was evidently a commonplace way to quench ones thirst and it was not widely associated with disease at that point.

John Snow explained that since cholera had disappeared in 1849, south London’s domestic water supply had significantly altered. Southwark and Vauxhall Company and the Lambeth Company were in competition, just like the pre-monopoly era at the beginning of the century. Their pipes ran side-by-side in certain districts. The parallel supply of different water provided an opportunity for Snow to further his thesis about the cholera tragedies recurring in London, and elsewhere. As he wrote: ‘Each Company supplies both rich and poor, both large houses and small; there is no difference either in the condition or occupation of the person receiving the water of the different companies…as there is no difference whatever, either in the houses or the people receiving the supply of the two water companies, or in any of the physical conditions with which they are surrounded, it is obvious that no experiment could have been devised which would more thoroughly test the effect of water supply on the progress of cholera…‘83 To aid his research, the Registrar General’s office agreed to provide the physician with the addresses of people as they died from cholera in those districts. Snow set about tracking the damage caused by the Lambeth Company’s water, whilst a doctor called John Joseph Whiting volunteered to take on the districts supplied only by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company. Snow recounted: ‘Mr Whiting took great pains with his part of the inquiry, which was to ascertain whether the houses where the fatal attacks took place were supplied with the Company’s water, or from a pump-well, or some other source.’84

One frustration for the duo was that residents often did not even know which company they, or their landlords, were paying. If the dwellers could not find any receipts for bills, Snow had a back up plan. He took a sample of water from each of the cholera-struck properties and performed a chemical test. Results were matched with the average sodium and chloride levels that he had already established in the two companies’ supplies. Over the four weeks of the epidemic, three hundred and thirty-four people died from cholera in the area that the two companies supplied. Snow and Whiting established that 286 of the households affected were supplied with water by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, whilst the Lambeth Company was found to be responsible for only 14 cases of infection.

Steven Johnson, author of a recently-published interpretation of Snow’s legacy, The Ghostmap, summed up the lukewarm response to the physician’s theory in those post-cholera years thus: ’…miasma retained its hold over many, and Snow himself was often subjected to derisive treatment by the scientific estab-lishment’ (for instance peers writing in The Lancet medical journal).85 The ideological gulf between the two schools of disease transmission continued but one clear decision was made as a result of the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers fieldwork. London’s ‘filth’, quite crudely, its faeces, needed to be removed.

In the same year that Snow’s revised, and now seminal, thesis On the Mode of Communication of Cholera was published, 1855, the Metropolis Management Act was passed. The Act’s implications were seismic. It would institute a governance structure for building the modern world’s first citywide underground water-based sewerage system, under the governance of the Metropolitan Board of Works. Painstaking surveying and designing by the Metropolitan sewer commissioners, including Joseph Bazalgette, had translated into a coherent set of plans for radical underground sewage works. New housing would be condemned if water closets failed to be ‘furnished…with suitable water supply and water supply apparatus’.86 Sewage was to be removed from sight, and therefore from contact with the air, and, most critically, it was to be discharged into the Thames in locations far removed from London’s population. These locations would also, therefore, be distant from points of water abstraction. Miasma theory was still going strong, but the vast plumbing system was equally instrumental in preventing water-borne disease transmission.

Governance to build London’s sewage system was in place, but the essential finances were not. Consequently, the subterranean makeover made a sluggish start. Sewage farms were already in vogue at that point, but any waterborne sewage entering the Thames, pre-1858, was raw. In 1856 the Board of Health’s Medical Officer, John Simon, published a report which examined the plausibility of cholera’s waterborne transmission, and though he was not entirely convinced about the veracity of John Snow’s theories, he admitted that more evidence pointed towards disease transmission via water rather air. On that basis he wrote: ‘Whether water can be securely drunk from rivers polluted by urban drainage, interests more or less every part of the country and whatever facts can terminate this doubt, bear upon every plan for the water supply of a population, and upon every plan for the drainage of a town.’87 In essence, Simon was questioning the natural capacity of a river to recover from sewage pollution. The answer lay in a method for examining water that could offer a definitive ruling on its quality for human consumption, but that science was still floundering.

Plans for sewers to bypass central London were still on the drawing board when the famous ‘Great Stink’ occurred. As temperatures rose in the summer of 1858, the stench from the Thames wafted into national newspaper headlines. The Era vented its disgust by suggesting that the Thames be renamed ‘the great sewer of London’.88 A visceral verse from The Morning Chronicle also conveyed the inhaling horror to its readers. Those remote from the Thames certainly got a vicarious whiff:

‘Piff, piff-piff! how horrid

Is thy filth, thick as cream,

Baked by Summer’s sun torrid,

It reeks with foul steam!’89

The excretions of two million people must have been quite a convincing olfactory argument, especially when they were lapping up against the river’s north bank at the Houses of Parliament. Promptly, the Government rushed through a bill to unlock funds for the Metropolitan Board of Works to get things flowing, out of central London.90 The historian Bill Luckin argues that the motivation to clean up the Thames was not only a result of the river’s impact on the quality of local life, but because of its secondary role as a symbol of the heart and power of the British Empire.91 A polluted Thames was a source of international humiliation. As Luckin argued: ‘To save the river was to consolidate the new urban-industrial order.’92

Within that industrial order, steam engines had by then revolutionised control over water distribution through vast pumping technology and therefore modes of production and consumption in turn. New technological water innovation would also be ushered in with the Local Government Act of 1858, which acknowledged that urban municipalities needed to invest in large-scale infrastructure to treat sewage before it entered rivers.93 On the sewerage front, London’s revolutionary sanitary engineering project led by Joseph Bazalgette transformed underground infrastructure during the 1860s, creating embankments such as Chelsea to house the pipes. How soon water quality would be transformed by sewerage and diseases like cholera extinguished remained to be seen.

Above ground, a minor clause in the 1855 Metropolis Management Act raised the issue of public water access: ‘Every Vestry and District Board shall have full Power and Authority to cause any Wells to be dug and sunk in such public Places as they think proper, and also to erect and fix any Pumps in any public Places, for the gratuitous Supply of Water to the Inhabitants of the Parish or District.’94 What this water might be used for was not specified, though it seems likely that it was intended largely for cleansing, of streets for instance, rather than primarily for drinking. If the sources were imagined for drinking use, it was a worrying proposal given the Broad Street example. Quite separately from the dictates of the state’s public health administration, public fountains were about to become extremely fashionable.