Purity and Poison: 1948–1969

‘Fluoridation is undoubtedly the thin edge of a totalitarian wedge.’1

(London Anti-Fluoridation Campaign, 1966)

Visions for the post-war landscape were drafted even before the conflict had ended. The London County Council published the first version of its County of London Plan in 1943. Housing was naturally central to restoring the stock depleted during the Blitz, however there was also a striking emphasis on the value of outdoor space and how principles of health could be embedded in those designs. As the plan’s authors believed: ‘Adequate open space for both recreation and rest is a vital factor in maintaining and improving the health of the people.’2 Other post-war optimists were The Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association, still in business, which announced to supporters in its 1945 report: ‘We are looking forward to a future of great activity in replacing structures destroyed in the raids and supplying new ones to the many Playing Fields and Open Spaces that are now being planned by Local Authorities.’3 The charity was not disappointed. 63 fountains were ordered in 1948 which was the highest number in a single year that the charity had ever installed.4

Creating healthy public spaces in that year was an apt expression of a new, socialist medical era. Britain’s National Health Service was born in 1948. Concern for public health was paramount to the ideals of the new Labour Government’s nascent welfare state, in which free access to healthcare represented an economic commitment to the principle of social justice and equality. Enshrined in the National Health Service Act was the ideal of preventing, as well as curing, illness.5 This chapter investigates how drinking water became a focal point in the debate over how to deliver this health philosophy of prevention and social equality in a mode that some people were not willing to swallow, under any circumstances.

Visions of Sparkling Teeth

It was in America that the notion of engineering public water to actively improve a population’s health first gained ground. News was coming from health professionals across the Atlantic of research and then, in 1945, a trial of chemically enhancing tap water’s nutrients with a naturally-occurring ingredient: fluoride.6 By 1950 American dentists were optimistic about the test results: ‘The fluoridation of public water supplies as a partial protection against tooth decay is a tremendous step forward in the profession’s fight against dental decay.’7 The subject of fluoridation entered international public health discourse. Though it was a national issue in Britain, London’s experience was contoured by its symbolism as the capital, and also by the complexity of the city’s local government structures. Records of the Metropolitan Water Board’s (MWB) involvement in the national and local fluoridation debate reveal a period of high emotion, characterised by clashing ideologies about drinking water as an instrument of public health.

MacKenzie remained the MWB’s Director of Water Examination after the war. His title was de-militarised by the 1950s from Colonel to plain E.F.W. MacKenzie. The decade had already seen London’s post-war austerity relieved during 1951’s Festival of Britain celebrations, when the South Bank was transformed into a twenty-seven acre site celebrating ‘British achievement in science, technology and industrial design’.8 If MacKenzie had taken a night-time stroll along the river during the festival, as one of the eight million people who visited, he would have shared the popular sight of a light spectacle illuminating iconic Thames-side buildings, light-based artworks projected into the sky, and even onto fountains and pavements.9 Whether or not MacKenzie enjoyed this sight, the scientist certainly appeared to share the Festival’s curatorial vision that the cross pollination of science and technology could enlighten the future of humanity through new innovations.

In spring 1952 MacKenzie gave a lecture at the Westminster Hospital Medical School. Its subject was fluoridation. His lecture took place midway through the trip of a team that had been dispatched by the British Government to research that very issue. The team had a grand title: The United Kingdom Mission on the Fluoridation of Domestic Water Supplies in North America. Before MacKenzie knew the outcome of that Mission’s findings, he was already convinced about the benefits fluoridation could bestow on the teeth of young Londoners, not to mention its effectiveness in cutting the National Health Service’s 43 million pound dental bill. This water examiner seemed at ease with his potential role in dispensing an improvement in London’s public health. For him it was merely a ‘daily supplementation of the fluorine intake in areas where it was known to be insufficient’ (fluorine is the name of the chemical in its pure, gaseous form).10 Importantly to the debate that would ensue, MacKenzie explained that fluoride was already present in all water, but at inconsistent levels. In some parts of America, fluoride levels were naturally higher than others. The effect this had on locals’ teeth was a visible mottling of the enamel. Research, initially prompted by this discolouration issue exposed fluoride’s agency both as a preventer of dental caries and as the culprit for mottling. When consumed via water, different concentrations of the naturally occurring chemical produced vastly different results.

MacKenzie relayed to the Medical School audience that extensive American-based research into fluorine during the 1930s and 40s had moved to water treatment in some States. America’s fluoride research had revealed how precise levels of the added chemical needed to be, in order to achieve the desired effect. As the Director explained from the conclusions of American scien-tists: ‘…reduction of caries’ incidence in school children might be expected from concentrations of fluorine of between 1.0 and 1.5 p.p.m.’ and critically that ‘no further appreciable benefit was obtained by a higher fluoride content.’11 Research underway in the United Kingdom, in the few places where fluorine was at high enough levels to compare with the American studies, was corroborating this view.

Equalising the natural substance involved using an artificial compound: sodium fluoride. Injecting the water supply with fluoride, according to MacKenzie, should not cause any controversy in Britain because of precedents demonstrated by other dietary supplements: ‘The ethics of so-called mass medication had been satisfactorily settled in such matters as improvement of flour by calcium, addition of vitamins to margarine or of iodine to salt.’12 One note of uncertainty that MacKenzie did sound was about the ‘possible harmful effects’ of fluorine.13 But there was no doubt from his speech that he was vociferously pro-fluoridation. In his closing words, he posed the American Public Health Association’s question about the un-fluoridated States: ‘“What are the rest of us waiting for?”’14 ‘The same question might well be asked, and indeed is being asked, in this country today’, Mackenzie concluded.15 During his sales-pitch, the Director of Water Examination neglected to mention one critical piece of information. Some segments of the American public were firmly opposed to mandatory fluoridation.

The tale of America’s Fluoride Wars interprets public response to the first artificial dose of fluoride in Michigan neatly: ‘For most, it was another blessing bestowed on us by modern science. But for some, it was one chemical too many.’16 Members of the United Kingdom’s fluoridation mission to the U.S. were well aware of the controversy the subject had ignited there. The visit coincided with the deliberations of a U.S. Government Select Committee, appointed to Investigate the Use of Chemicals in Foods and Cosmetics. 17 In media coverage of the Committee’s proceedings, opponents to fluoridation were prominent as the national fluoridation debate ramped up. The U.K. investigators also felt the formidable force of local pressure groups, whose members engaged in public deliberations about the merits of fluoridation. Anti-fluoridation lobbyists in Seattle held enough sway to swing the pendulum completely against the proposed additive.18

Tampering with the Tap

Within the MWB’s records, the first murmur of opposition to fluoridation in London came from the manager of the Housewives Today publication, the mouthpiece of the British Housewives League. In January 1953, a letter sent to the Board, penned by Mr H.F. Marfleet from Stepney Green in East London (clearly not a housewife himself), raised this concern: ‘I’ve heard a rumour that the water supply of the metropolitan area is to be treated with fluorine, which is supposed by some people to be a preventative of dental caries.’19 Marfleet wanted to reassure Housewives Today’s readers that the rumour had no basis. The Board’s response left the rumour open to further speculation: ‘There are no regulations regarding the amount or quality of any substance that may be added to the water. The possibility can, however, be envisaged of the Ministry making regulations in such matters.’20 It was quite a revelation that additions to the water supply were, in fact, totally unregulated. Chlorine was simply accepted as a necessity.

Four months later, Mr Marfleet issued a complaint: ‘As a consumer of Metropolitan Water, I write to register my strong disapproval, and respectfully to ask you to represent this opinion to the Board.’21 Marfleet feared ‘mass medication’ would soon be pouring out of his kitchen tap. The same year, the U.K. fluoridation mission to America published its report, which MacKenzie shared with his water examination committee. Fluoridation’s positive impact on dental health was endorsed, as a health measure to top up levels of the substance in areas where it was deficient. MacKenzie acknowledged that public suspicion had to be addressed because of the ‘flood of propaganda leaflets and articles’ opposing the measure.22 So despite the endorsement of America’s fluoridation policy, the U.K. Mission and the Government remained cautious.

Examples of public opposition in America were cited as grounds for the suggestion that Britain needed its own trials, to supply British-based evidence. A flicker of scientific doubt was also expressed in the U.K. Mission’s report: ‘…evidence of harmlessness is so strong as to be almost conclusive.’23 Almost harmless was clearly not the same as absolutely harmless. The state’s line was to encourage more research about the long-term health effects of ‘low levels of fluoride’.24

The Times reported from the House of Commons in December 1953 that the Minister for Health, Mr MacLeod, had announced that ‘selected communities’ would soon experience fluoridation trials. Later on, Norwich was revealed to be one of those trial communities. However, the motion to commence the experiment there was defeated by Norwich City Council in June 1954. ‘City refuses to be Guinea-Pig’ ran the Manchester Guardian’s banner headline.25 Fifty complaint letters had been received by the Council and none of them were positive about the fluoridation plans.

Four other trials were imminent: Anglesey (North Wales), Kilmarnock (Western Scotland), Andover (Hampshire) and Watford (Hertfordshire).26 London remained exempt, as Watford lay beyond the MWB’s boundaries. Before the trials began, in July 1955 the Ministry of Health issued a ‘reference note’ to equip health, local governments and water authority officials to defend the virtues of fluoridation.27 State rhetoric was pitched against increasingly public anti-fluoridation sentiment, encapsulated by one emotive Picture Post article entitled ‘Hands Off Our Drinking Water’. Could fluoride enter foetuses or infect breast milk, asked its author?28

Language was carefully employed in the Ministry of Health’s Reference Note to neutralise the polarised debate. Controlled ‘demonstrations’ rather than ‘experiments’ were to take place.29

Emotional anti-fluoridation arguments were also addressed in the note, including the belief that fluoridation was poisonous. The Ministry’s experts argued that only ‘exceedingly high concentrations of fluoride’ i.e. of the kind used in industrial processes were known to cause any harm to the human skeleton.30 It also reassured readers that most fluoride would be excreted in bodily fluids or absorbed as a natural component of the bones. The point that fluoride naturally occurred in all water supplies, and therefore already entered the human body was driven home: ‘What is proposed is to make good a deficiency in those water supplies which lack this beneficial element…’ [publication’s bold].31 Fear was also tackled by the assurance that the fluoride compound to be used in the demonstrations was ‘indistinguishable from the naturally-occurring fluoride ion’.32 Highlighting the chemical composition of water in its raw state ruptured the notion of purity to which anti-fluoridationists clung. What was pure drinking water? The Ministry of Health’s answer was crystal clear: ‘If it is argued that the addition of fluoride to water affects the “purity” of the water, it can be answered that water in nature is never chemically pure and that most waters have to be treated chemically before they are suitable for supply, about thirty chemicals being used in water works to produce clear and wholesome water suitable for domestic and industrial purposes.’33 (This was quite an admission.) Of those chemicals, chlorine was paraded as a precedent for why adding substances to raw water, as well as taking them away, could be so beneficial to public health. Like chlorine’s prevention of bacterial havoc, the experts argued, fluoride was an equally preventative measure for the health of future generations.

Fluoridation in Andover officially commenced after the trials in 1956 but was arrested by summer 1958 due to public pressure and local councillors failing to be re-elected over this single issue.34 In Darlington, the Council’s decision to try out fluoridation was reversed before trials even began, inspiring other fluoridation opponents to keep campaigning, such as the British Housewives League.35 In 1959, the League published a pamphlet entitled Fluoridation — Why and How to Stop It. The focus of its opposition was now focused on enforcing fluoridation without individual consent: ‘The “doctoring” of the public water supply with a substance intended to affect the human body without consent and contrary to the wishes of many consumers, is a violation of such a [human] right.’36

Whilst the Housewives League pamphlet was circulating, unbeknownst to its authors, the MWB had commenced fluoridation tests.37 An internal report divulged that some trials had been made on live works but that the water had not been released into supply. These decisions were under the watch of a new Director of Water Examination, Edwin Windle Taylor. His perspective on fluoridation was less gung-ho than MacKenzie‘s, but it was evident that he was poised to flick the fluoridation switch if the other English trials were evaluated as successful.

Before those results came through, in 1960 H.F. Marfleet had resumed correspondence with the Board and was told that a decision about fluoridation had been suspended until the results of the trials were made public, due in 1961.38 Seemingly unsatisfied by this assurance, Marfleet changed tack. A further letter demanded that he be supplied with a list of the 88 names and addresses of each Board member. Anticipating the deluge, the Board’s Clerk primed members with a missive about the unfriendly post they might receive. If Mr Marfleet did indeed hammer 88 letters out on his typewriter, copies have not been preserved for posterity in the MWB’s archives. Also in 1960, the anti-fluoridation movement consolidated under the umbrella of the National Pure Water Association and the battle marched, with more troops, into a new decade.39

In 1962, the long-awaited report on the United Kingdom’s fluoridation trials was delivered.40 The Director of Water Examination reported to his team that the results wholly endorsed American research and that, in the trial areas, five-year-olds’ instances of caries had halved since 1955–56.41 Windle Taylor also wrote that ‘no information was received from doctors practising in the areas indicating any harm arising out of fluoridation’.42 A decision was due on whether the Board would fluoridate London, or not. The legal-technical structural problem this presented mobilised the British Waterworks Association, the national umbrella body for the waterworks industry, of which the MWB was a member. In October 1962, it called for Parliament to act on the matter, on the grounds that fluoridation extended water providers’ remit beyond providing wholesome water.43 The Association argued that legislation was needed ’…before any water authority can accept responsibility for the addition of fluoride to the public water supply’.44

On 10th December 1962 the Minister of Health, then Enoch Powell, announced to Parliament that, under Section 28 of the National Health Service Act, he was approving ‘proposals from the local health authorities to make arrangements with water undertakers for the addition of fluoride to water supplies which are deficient in it naturally’.45 In the House of Lords, Lord Douglas of Barloch was clearly outraged by the decision, when he spoke: ’…may I ask the noble Lord whether consideration has been given to the problem of whether it is legal to add medicines or drugs to public water supply? May I also ask why fluoride should be forced down the throats of everybody, whether they have teeth or not?’46

Within days the MWB received a letter from the Ministry of Health permitting it to commence fluoridation, reassuring the Board that local authorities and water undertakings would both be indemnified against any Court proceedings post-fluoridation.47

However, that year a question mark hovered over the MWB’s future as legislation was being fine-tuned for a major restructuring of London’s governance.48 In 1963, the London County Council was abolished and replaced with the Greater London Council, which would function alongside 32 local borough councils.49 From 1965, London’s geography would be defined by 610 rather than 117 square miles. This political restructuring embedded health within the new borough councils, which would also function as local health authorities.50 These authorities would therefore decide whether to fluoridate, or not. Around this vast conurbation, the MWB would still serve up the vast majority of the population’s water (apart from some peripheral areas) irrespective of borough boundaries. Perhaps anticipating that fluoridation would prove to be an emotive topic in local politics, in May 1963 the Board clarified an important practical point about the prospect of London moving to fluoridation. Internally, the Water Examination Committee’s Clerk declared: ‘I am informed by the Chief Engineer that if the Board decide to adopt a policy of fluoridation, there is little or no possibility of keeping the supply to any particular area free from fluoride. In other words, none of the local health authorities could opt out of the scheme.’51

Just days later this private statement became public policy. The MWB would not be ‘required to make a decision on the compulsory administration of fluoride to 2,500,000 people’ without the unanimous approval of London’s health authorities.52 Doubts about transcending its duty as a supplier of pure water rationalised the decision, along with examples of international controversy. Of these, America’s legal battles were cited along with opposition from medical professionals in Australia. The latter was an important example of anti-fluoridation opinion within the peer-reviewed sphere of the scientific establishment, rather that the spurious factual claims delivered by some lay opponents.

Despite London’s fluoridation stalemate, in June 1963 the Ministry for Health issued unequivocal approval for all local health authorities to start introducing the measure as soon as possible.53 Authorities were to instruct their water undertakers and simply inform the Ministry when, rather than if, fluoridation would be commencing. The Ministry of Health also issued a publication, simply entitled Fluoridation. The booklet confronted the core criticisms of ‘a small but vocal minority’ and its tone was urgent.54 For instance to the question ‘Is fluoride a poison?’, the anonymous author retorted: ‘It would be necessary to drink at one time two and a half bathfuls of water containing fluoride at a concentration of 1p.p.m. before any harmful effects due to fluoride would be experienced.’55 Scornful, if slightly comical, statements such as this seemed out of place in an official state publication, perhaps only hinting at what views might have been less-delicately expressed behind the Ministry’s closed doors. Fluoridation also contested the interpretation of an adjective favoured by the anti-fluoridation lobby: ‘pure’.56 Readers were reminded that raw water contained traces of many chemicals. But the more pervasive question about fluoridation had moved to more ideological territory: ‘Are personal liberties infringed?’57

Popular concern about environmental toxicity was linked to the health-food zeitgeist. A resident of Stoke Newington, an area associated with alternative culture and politics, wrote to the Board in August 1963: ‘Surely the only and best way to combat decay in children is more fresh fruit and vegetables, 100% whole-wheat bread, regular meals and brushing clean after each?‘58 Her view was representative of an international swell of concern about industrialised food production. In America, for instance, the publication of Silent Spring by the scientist-cum-environ-mental-activist Rachel Carson in 1962 is credited with inspiring the organic food movement and creating the scientific discipline of ‘environmental toxicology’.59 Public outrage caused by the revelations in Carson’s best-selling book about chemicals entering the food chain, and killing wildlife, influenced John F. Kennedy to launch a U.S. Government enquiry into pesticides’ impact on the environment.60 This issue infected British scientific and public discourse, but the response in London was also a product of post-war and Cold War concerns about state interference in the private lives of individuals

By the 1960s, one of the more inflammatory phrases used in anti-fluoridation literature in Britain was ‘compulsory mass-medication’.61 In a document entitled The Ethical Question is Paramount, the National Pure Water Association wrote the following: ‘…it is subversive of personal freedom and medically, socially and politically unethical to use the public water supply as a vehicle for administering to the public any substance which is intended to treat the human body.’62 Reaction to fluoridation’s green light by the Ministry of Health in summer 1963 was met with this and many more arguments.

In August 1963 the Board wrote to the London Anti-Fluoridation Campaign (LAFC) complaining that one of the Board’s customers had received a postcard from the Campaign with the following message: ‘It is proposed to put a poisonous substance in your water supply.’63 With barely concealed exasperation, the Board’s Clerk wrote that the LAFC was warning people that London’s water was about to be treated with fluoride, when it already knew that no such decision had been made; at least not by the Board.64 The Clerk requested the Campaign to stop issuing the postcards, however, by November some 20,000 of these postcards had fluttered through Londoners’ letterboxes. The Times reported the story, quoting from the besieged Clerk: ‘Dozens of people have written to us saying, “Why are you trying to poison us?” and “Stop it immediately“. Many of them are extremely angry.’65

This correspondence was the start of many years of heated communication between the LAFC’s Chairman, Patrick Clavell-Blount and the MWB. Having served in the RAF as a catering officer, Clavell-Blount did not believe that the war had been fought for a Welfare State system that was, in his view, corrupt.66 Several anti-fluoridation activists were serial correspondents to the MWB, however Blount was especially prolific. He produced missives such as Fluoridation: A Monstrous Violation of Human Rights. That publication claimed that ‘fluoridation was one of the greatest infringements of individual freedom ever to have been attempted in a civilised country’.67 More understandable was his and others concerns about the long-term health impacts of artificially fluoridated water. The LAFC was somewhat dominated by the voice of Patrick Clavell-Blount, but more powerfully placed anti-fluoridation organisations also bore on the fate of London’s water supply and, consequently, its population’s dental health. Lord Douglas of Barloch, as the President of the National Pure Water Association, wrote to the Board promptly following the Minister’s instructions to health authorities to proceed with instigating fluoridation. The Lord claimed that under existing legislation it would be ‘illegal for water undertakers to add fluorides to their supplies’.68 His warning was bound to make London’s water supplier nervous about the solidity of the Ministry of Health’s legal protection.

In the records of the Board, the file entitled ‘Fluoridation: Supporters’ is noticeably slimmer than any of the many ‘Fluoridation: Objectors’ files. One of the few supporters was Marjery Abraham, who wrote: ‘I enclose [a] cheque for my colossal rate. I shall feel it is worthwhile when [you] have made up the fluoride content of the water. You have delayed far too long in my opinion. The propaganda against it is misleading and disgraceful.’69 A second letter pronounced the anti-fluoridation lobby to be ‘ignorami and fanatics’.70 Unsurprisingly amongst other supporters were the British Dental Association and the Royal Dental Hospital.

Whilst London’s water remained ‘pure’, in 1964 Birmingham took the fluoridation plunge. It was the first city to adopt fluoridation as an outright policy, rather than a demonstration. Birmingham’s health authority was convinced that it was a sound preventative health-care investment, in a place where ‘three-quarters of the city’s children had dental caries by the age of five’.71 Calculations showed that upwards of £90,000 was likely to be saved by the city’s health authority in the move from treatment to prevention.

In November 1965, the Minister of Health, Kenneth Robinson addressed the London Boroughs Committee. His speech applauded the capital’s complex democracy but decried that it was resulting in the denial of social justice to young citizens. He pleaded with the councils resisting fluoridation: ‘I hope all concerned will recognise in their turn the vital importance of their decision to the children of London…[and] not deny the community they serve.’72 ‘All concerned’ were not ratifying national health policy and, despite his pleas, London’s fluoridation question was still unanswered in 1968.

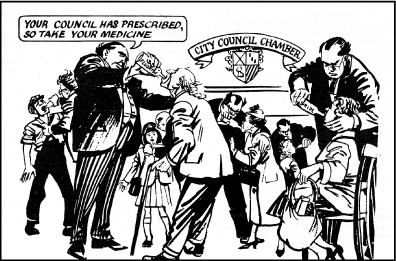

Front cover of London Anti-Fluoridation Campaign pamphlet, 1966

Author unknown. City of London, London Metropolitan Archives.

In the meantime, the Metropolitan Water Board issued numerous stock responses to concerned members of the public stating that health authorities rather than the supplier were ultimately responsible for that fluoridation decision.73

Un-Britishness

To clarify the uneasy position of the Board, it wrote to each of the local health authorities to establish which were in favour of fluoridation or not.74 Responses were tallied in spring 1968. Twenty-four were pro-fluoridation, two had approved it in principle and nine were against the measure.75 The influential City of London Corporation was an anti-fluoridation island surrounded by boroughs favouring fluoridation such as Southwark and Tower Hamlets. Other opposing borough and county councils were curiously concentrated on the outer edges of the city; Brent in the north and Sutton to the south. Inner city poverty, with resultant poor oral health of many young people may well have been more visible to those in central London. Translated into approximate populations, the opposing areas added up to 918,100 people whilst the pro-fluoridation majority was 6,219,600.76 Still, the principle remained that the water supply could not be cordoned off to exclude those areas, such was the nature of the technological network and water’s very nature as a fluid.

On 26th April 1968 the Board declared an amendment to its own stance on fluoridation: ‘That it be recommended to the Board that they take no policy decision with regard to the fluoridation of London’s water supply pending the outcome of the Birmingham fluoridation scheme, or the introduction of government legislation on the subject.’77 In May 1968, a small article in London’s Evening News publicised the Board’s policy decision with the headline ‘No Fluoride for Londoners’ Teeth’.78

As legislation, or a change of mood, in the opposing councils was awaited protest continued into 1969. A statement issued by Patrick Clavell-Blount’s London Anti-Fluoridation Campaign was decorated with a list of prominent signatories from the Houses of the Lords and Commons, including the violinist Yehudi Menhuin. ‘…we do not consider such medication has any place in the British way of life’, declared LAFC’s supporters.79

Even in 2012, fluoride has yet to be artificially added to London’s supply. The latest enquiry into the subject, convened by the Greater London Authority, published a report in 2003 and advised against the chemical’s introduction. This recommendation was made on the basis of the consent needed from five strategic health authorities in collaboration with four water suppliers.80 Mass medication was not cited as a reason for the enquiry’s conclusion, yet the subject of environmental toxicology is, rightly, remains a current concern.

Public Fountains in Decline

During the span of the anti-fluoridation campaign, a sense of pride and trust in the quality of public water is apparent. That sentiment was perhaps unknowingly reinforced by an international set of Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, which were first published by the World Health Organisation in 1958. One reason for their establishment was the rise in debate about drinking water safety amongst those enjoying international air travel in the 1950s.81 Although the United Kingdom was one of the key nations informing the science for these standards, at that point no law for precise drinking water standards had been passed. Faith in tap water did not appear to be affected by absence of legislation in the 1950s and 60s.

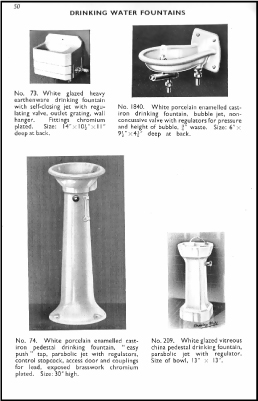

Outside the home, drinking water was promoted by modern fountain designs suitable for a variety of potential indoor, public locations. As demonstrated by the drinking fountains in Thomas Crapper’s 1954 Puritas range, the modernist bubble jet invented in the 1930s was still in vogue. In gleaming white porcelain and china, the bounty of pure water produced by modern industrial nations could be relished from these hygienic objects.

Drinking Water Fountains. Crapper Puritas, Catalogue No. 30, Thomas

Crapper and Co. Ltd. 1954, p. 50.

Crapper’s catalogue does not tell which organisations purchased and installed the Puritas models, but the range of four designs suggest a demand for drinking fountains as a somewhat utilitarian sanitary ware. Puritas fountains may well have been exported internationally, but it is likely that some of these designs could be found later that decade in schools, hospitals or other public institutions and places of work. Certainly the 1937 Factories Act stipulated that a supply of wholesome drinking water had to be supplied by employers.82 Though the word fountain did not appear in the legislation, a device featuring an ‘upward jet’ was specified. Thomas Crapper’s elegant ceramics would not have survived for very long outdoors, where the public fountain idealism of the post-war years was facing some challenges.

The Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association pointed out the ‘menace of vandalism’ to supporters in its 1968 annual report: ‘It is a regrettable fact that, without close supervision at all times, fountains are only too likely nowadays to be put out of action at the hands of hooligans. Consequently our activities are now largely directed towards the provision of fountains in parks, public gardens, playing fields and children’s playgrounds, which can be closed and secured when not in use.’83 The organisation’s retreat from the street had been prefaced by a move from Victoria Street, where it had been based since 1872, to the suburbs in 1960.84 Though a high profile office location was surrendered that year, a prestigious new pair of drinking fountains were also inaugurated within the walls of London’s most iconic public space: Trafalgar Square. The Association’s 1960 report noted that its Chairman ‘was again invited by the B.B.C. to appear on television in connection with the installation of the fountains’.85 A public drinking fountain in a striking location was evidently still a newsworthy item.

In an informal survey conducted for this book, many Londoners of the post-war era testified to using drinking fountains habitually. Ron Brooker confirmed that fountains flowed in his south London borough during the ‘50s: ‘At that time Croydon’s Park Department ran and maintained the town’s parks very well.’86 One respondent commented on water pressure problems with his local fountain, but still recalled using it. David Khan remembered using the bubble jet ‘press-down tap that allowed a flow to bubble upwards, enabling a drinker to partake without any direct contact with the actual outlet’.87 Hygiene fears did not seem to preoccupy many respondents, who described how they freely drank from the clunky metal cups, many of which were still firmly affixed to nineteenth-century models. Lesley Ramm remembered of Priory Park, in Hornsey: ‘As children we used the old metal cups, attached by chains, to scoop water from basins on hot summers days after playing.’88 And in Clapham Common, Peter Skuse also used the fountain’s metal cups, with this proviso: ‘My Dad had told me to dip only my lips into the water in the cup.’89 At that four-sided fountain, a strict protocol surrounding the cups’ use developed: ‘As we grew older, we would collectively adopt one cup, and take it in turns, leaving the others free for other children; indeed I recall once at least where we defended a cup against bigger boys, letting smaller girls and boys drink while they had to wait for another to become free. Someone saw us that day, and gave us a bag of Sharps toffees for being public-spirited!’ By 1960, he claimed that the fountain was dry, but other areas of London were still in receipt of public hydration. For instance, Virginia Smith recalled of her Hampstead neighbourhood and elsewhere: ‘You would always expect to have a fountain in a park, though some were fancier than others.’90 Bernard Pellegrinetti clearly remembered the ‘old fashioned fountain’ near Kenwood House, also in Hampstead, where he and his brother regularly refreshed themselves.91 Lesley Ramm noted a gradual disuse and total disappearance of public fountains: ‘I think they were working into the 1970s but when the council withdrew Park Wardens and Gardeners, the park became a no-go area and much was vandalised.’ Ron Brooker concurred that ‘in later years, one noticed park drinking fountains not working and that was probably due to neglect by the local councils’. The ideals of the welfare state’s healthy urban parks were slowly rotting, as the investment in public services from the state dwindled.

One thing that is certain from the 1950s and ‘60s era of fluoridation and fountains is that Londoners were drinking water, whether it was indoors or outdoors. Valerie Scott, who also responded to the fountain survey, pointed out ‘there was no alternative in the days before bottled water’.92 The anti-fluoridation campaigners were possibly so worried about the proposed additive because they were aware of how intrinsic tap water was to their diets and daily lives. Bottled water’s proposition as a more ‘natural’ product than tap water did not arise in the records of the fluoridation debate that this chapter’s research consulted. Possibly this was because fluoride naturally occurs in mineral or spring water sources but, more likely, because bottled water was uncommon and expensive. Mineral waters from Bath or even Schweppes Table Water remained elite, not everyday products. So how did Londoners develop such a penchant for bottled water by the late 1980s?