DAIRY PRODUCTS: MILK, CHEESE, AND EGGS

Dairy products are foods made from milk. Because eggs and margarine are stored in the grocer’s dairy case, however, we have included them in this section as well. It is impossible to know when humans started to eat dairy products. Cows, goats, sheep, and yaks have been raised and kept for their milk for thousands of years. Today, the cow is the primary milk-producing animal worldwide, and the international dairy industry is built on the output of this friendly animal. Except where otherwise noted, any mention of milk here refers to cow’s milk.

MILK AND MILK PRODUCTS

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration calls milk “one of the best controlled, inspected, and monitored of all food commodities.” Truly, the milk industry is more carefully monitored by federal and state health authorities than any other food-related industry.

Whole milk is approximately 87 percent water and 13 percent solids, which include fat, protein, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. The daily output of a dairy cow ranges from about 12 to 25 quarts of milk. Holstein cows, which are among the most prolific milk manufacturers, can produce 40 quarts daily. The most milk produced by a single cow on a regular basis is 60 quarts per day!

Unless it is certified raw, milk typically undergoes three specific processes: pasteurization, homogenization, and fortification.

Pasteurization is the heating of milk at 161°F or above for fifteen seconds to destroy any pathogenic, or harmful, bacteria that may be present. Pasteurization destroys yeasts, molds, and almost all nonpathogenic bacteria as well as enzymes that promote spoilage. Thus, pasteurization makes milk a safer product and extends its shelf life.

Ultra-pasteurization is the heating of milk at 280°F for at least two seconds to ensure the total destruction of virtually all microorganisms. Ultra-pasteurization further extends the shelf life of milk while reducing its nutritional value somewhat, as the high heat can destroy vitamins. This process is used primarily with cream products.

Homogenization is a process by which the fat globules in milk are emulsified by mechanical means until they become so tiny that they remain suspended evenly throughout the product, thus maintaining uniform consistency. Homogenization is not required by law, but most milk sold commercially is homogenized. In nonhomogenized milk, the cream rises to form a layer on the surface.

Bovine Growth Hormone: Just Say Moo!

According to the Monsanto Corporation, cows are now living better through chemistry, pumping out as much as 25 percent more milk per day. This is thanks to recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH, also known as recombinant bovine somatotropin or rBST). This genetically engineered hormone is similar to one secreted in the pituitary glands of cows that plays an important role in milk production.

Though Monsanto and the Food and Drug Administration insist that rBGH is not biologically active in people, there is still great concern about its safety. Milk from cows treated with rBGH has a slightly higher level of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), the protein responsible for growth. A study in the January 1996 issue of the International Journal of Health Services concluded that consuming milk from cows treated with rBGH increased one’s risk of breast and colon cancer. Other studies have shown that IGF-1 is associated with glucose intolerance, hypertension, and swollen limbs. Cows given rBGH are subject to mastitis, and their milk is more likely to contain residues of antibiotics.

The National Farmers Union, several midwestern state legislatures, and many commercial dairies did not want rBGH approved. In 1988 the European Parliament recommended that meat and milk from animals administered this drug should not be fed to people or animals. The Netherlands has banned further research on the drug, and three Canadian provinces (Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta) have followed suit. The FDA, on the other hand, which bows constantly to commercial interests, approved the drug.

The result is big profits for Monsanto but almost certain economic homicide for many of the nation’s dairy farmers. Use of the drug increases milk production, decreases milk prices, escalates veterinary costs, and may well force a large percentage of smallto medium-sized dairy farmers out of business.

Fortification is the addition of nutrients, notably vitamins A and D. These vitamins are added to milk in the form of concentrates. If fortified, milk must contain not less than 2,000 international units (IU) of vitamin A and 400 IU of vitamin D per quart. These amounts must be stated on the label. The supplements used to fortify milk are synthetically manufactured and usually contain antioxidant preservatives.

Besides vitamins supplied by fortification, the primary nutritional factors in milk include protein, fat, carbohydrates, and calcium.

Protein accounts for about 38 percent of the nonfat solids of milk. The primary protein in milk, 82 percent of it, is casein, which contains all the essential amino acids. The essential amino acids are not manufactured by the body and must be obtained from dietary sources. Whey proteins make up the remaining 18 percent of milk protein. The proteins in milk are high in quality and play an important role in building and repairing body tissue and in forming antibodies, hormones, and enzymes.

Fat. Whole milk contains at least 3.25 percent milk fat. The composition of milk fat includes over five hundred various fatty acids, about 66 percent of which are saturated. These fats are a source of concentrated energy and are readily metabolized by the body. Milk fat, however, is also a source of dietary cholesterol. An eight-ounce serving of whole milk contains 33 milligrams of cholesterol as well as 150 calories. Because of its fat and cholesterol content, whole milk is to be avoided by dieters or those with a high blood cholesterol count.

Carbohydrate/Lactose. The primary carbohydrate in milk is lactose, otherwise known as milk sugar. Lactose accounts for about 55 percent of the total nonfat solids in milk. Lactose is a source of energy and promotes the growth of beneficial bacteria in the intestinal tract. About 20 percent of the U.S. population, however, is lactose intolerant. These individuals lack sufficient lactase, the enzyme that breaks lactose down into its component sugars. Common symptoms of lactose intolerance are stomach cramps, bloating, and diarrhea. The test to determine whether an individual is lactose intolerant involves measuring the amount of hydrogen expired in the breath after the person has ingested a quantity of lactose. Lactose intolerance is more common among blacks and Asians than among whites. To help with this problem, there are lactose-digesting enzyme products, in liquid and in tablet form, available in natural food stores. There are also some lactase-fortified milk products.

Storage and Handling

To keep milk products as fresh and usable as possible, observe the following guidelines:

Categories of Milk and Milk Products

CERTIFIED RAW MILK

In many states you can buy certified raw milk, which is not pasteurized but is regulated by the stringent standards of the American Association of Medical Milk Commissions. The production of certified raw milk involves regular veterinary examination of cows, sanitary inspection of milk production facilities, and medical examination of employees working at the dairy. These standards ensure a safe, wholesome product.

Dioxin in Milk

In the summer of 1988, Canadian scientist John Ryan determined that a form of dioxin called TCDD, which is found in cardboard milk cartons, migrates into the milk. Dioxin, the most potent cancer-causing agent known, gets into paper products during the chlorine bleaching process. The EPA says that 1 part per trillion of TCDD poses an unacceptable cancer risk. Avoid cardboard cartons whenever possible.

Often preferred by health enthusiasts, goat’s milk is sometimes tolerated well by those who cannot tolerate cow’s milk. Goat’s milk contains 165 calories and 10 grams of fat per cup, compared with whole cow’s milk at 150 calories and 7.75 grams of fat per cup. The fat globules in goat’s milk tend to be smaller than those in cow’s milk, which may contribute to enhanced digestibility. Goat’s milk is deficient in both vitamin B12 and folic acid but contains more vitamin A and calcium than cow’s milk. Goat’s milk has no “goaty” odor or taste if properly refrigerated after milking.

LOW-FAT MILK

Low-fat milk contains milk fat ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 percent. To be shipped interstate, low-fat milk must be pasteurized and fortified with vitamin A.

SKIM MILK

Skim milk is milk that has had as much fat removed as is possible by current methods. Pasteurization and fortification requirements are identical to those of low-fat milk.

LOW-SODIUM MILK

This is milk that has had approximately 95 percent of its naturally occurring sodium removed by ion exchange. It is pasteurized and homogenized.

FLAVORED MILK

Milk can be sold flavored, colored, and sweetened. Most flavored milks are sweetened with refined sugar. Some small dairies, however, make chocolate milk with whole cocoa and Sucanat or some other unrefined sweetener. Chocolate milk naturally contains approximately 5 milligrams caffeine and as much as 99 milligrams theobromine (a caffeinerelated alkaloid with diuretic and stimulant qualities) per cup.

EGGNOG

Eggnog contains milk products (usually milk and cream), eggs, and some sort of sweetener. It can also contain artificial or natural flavors, artificial colors, stabilizers, added butterfat, and salt. Some small dairies do make a “clean” eggnog at holiday time, using only milk, cream, eggs, and a natural sweetener such as honey, with a touch of vanilla. Eggnog must be pasteurized. It is absurdly high in fat and calories and typically delicious.

Low-Cholesterol Milk?

While whole milk contains approximately 532 milligrams of cholesterol per gallon, researchers at Cornell University have developed a process to reduce cholesterol in milk to just 40 milligrams per gallon. Dr. Syed Rizvi and his associates inject carbon dioxide into butterfat at high pressure. The butterfat, which is high in cholesterol, is removed from the milk, manipulated to extract much of the cholesterol, and then added back into the milk. The result is a much–lower-cholesterol milk with 2 percent butterfat, which tastes like any other 2 percent milk. The dairy industry is taking a serious look at low-cholesterol milk as the possible health wave of the future. Does this process destroy nutrients or otherwise harm milk? We don’t yet know.

EVAPORATED MILK AND EVAPORATED SKIM MILK

Milk is evaporated by heating, stabilizing the proteins, and concentrating the product in a vacuum to remove 60 percent of the water. It is then fortified and canned. Total milk fat is not less than 7.5 percent, and milk solids are not less than 25 percent. Evaporated milk must be homogenized and must contain 25 international units of vitamin D per fluid ounce.

Evaporated skim milk is skim milk that has undergone the same process. It contains not less than 20 percent milk solids, and not more than 0.5 percent milk fat. It does not need to be homogenized, but it must contain 125 IU of vitamin A and 25 IU of vitamin D per fluid ounce. Evaporated milk is not sweetened but is highly processed.

SWEETENED CONDENSED MILK

This is evaporated milk with sugar added and is not a particularly healthy product.

BUTTERMILK

Buttermilk originally was a by-product of the arduous manual butter-churning process. Known to have been consumed for more than five thousand years, buttermilk is now a cultured milk product. Buttermilk is typically made with lowfat or skim milk, which is pasteurized at 185° to 190°F and then cooled to 70° to 72°F. After cooling, cultured bacteria are added to the milk. These include Strep-tococcus lactis, Streptococcus cremoris, Leuconostoc citrovorum, and Leuconostoc dextranicum bacteria. The mixture is then incubated for about twelve hours at 68° to 72°F until the bacterium has converted some of the lactose into lactic acid, which gives buttermilk its characteristic tangy taste. The milk is then stirred and cooled to halt fermentation. Buttermilk may contain salt and stabilizers. Read the label.

ACIDOPHILUS MILK

Acidophilus milk is milk cultured with Lactobacillus acidophilus, a friendly bacterium that helps to maintain intestinal flora. Acidophilus milk has a slightly acid flavor and is typically drunk to enhance digestion.

NONFAT DRY MILK

This is pasteurized skim milk with all the water removed. The water is removed by either jet-spraying the milk into hot air or jet-spraying hot air into the milk.

LACTASE MILK

This is milk to which lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose (milk sugar) into usable component sugars, is added. Lactase milk is useful for those who are lactose intolerant.

YOGURT

One of the oldest fermented milk products known, yogurt is produced by heating milk to destroy harmful bacteria, cooling the milk down, and adding the live cultures Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. These cultures aid digestion, make milk more digestible for those who suffer from lactose intolerance, stimulate the immune system, and combat diarrhea.

While all yogurts are made with live bacterial cultures, some yogurts are pasteurized after being cultured, thus destroying those bacteria. The World Health Organization and the Food and Agriculture Organization specify that yogurts must contain live, active cultures. In the United States, however, a product may be called yogurt even if the bacteria have been destroyed by pasteurization. You don’t want yogurt with dead cultures. Yogurt that has not been pasteurized after culturing will state on the label: “with active yogurt cultures,” “living yogurt cultures,” or “contains active cultures.” If a yogurt label doesn’t say this, then assume that the bacteria in that product are dead. Yogurt may contain additives, including nonfat dry milk, sweeteners, flavorings, fruit preservatives or purées, colorings, and stabilizers, including gelatin. If you are buying flavored yogurt, look for a product with live cultures, with a natural sweetener and fruit only. Avoid yogurts that contain artificial colors and flavors.

Yogurt with live cultures is valuable for those who have taken antibiotics. Antibiotics destroy important intestinal bacteria, and yogurt helps to replenish them.

Another cultured milk product, kefir has been in use for thousands of years in the Caucasus mountains in Russian Georgia, whence this marvelous drink originates. Kefir is made by inoculating heated milk with kefir grains, which are made from insoluble milk caseins removed from previous batches of kefir. Kefir is high in B vitamins, enhances digestion, and restores intestinal flora. Kefir is sold plain or flavored. As with yogurt, look for kefir that contains active cultures without artificial additives.

BUTTER

Butter is made from milk from which the cream is separated and churned, and contains not less than 80 percent milk fat by weight. It may be salted or unsalted. Butter has come under fire over the past several years because of its high fat and cholesterol content. One tablespoon of butter contains 36 milligrams of cholesterol. Although eating a lot of butter can be a direct route to a fat, cholesterol-laden body, butter is still better for you than margarine. If you want a spread for a piece of toast, use a small amount of butter. If you are used to cooking with butter, try using a very small amount of butter mixed with olive oil.

MARGARINE

This pseudo-butter was originally made from lard but is now typically made from hydrogenated vegetable oils. Hydrogenation is a process by which hydrogen is added to oils to turn them solid. This creates a saturated fat, which is the type of fat that causes the body to produce cholesterol. Margarine, which often contains artificial flavors and preservatives, offers no advantages over butter. Although heavily promoted on television as though it were healthful manna from heaven, margarine contains the same amount of calories as butter and may actually cause the body to produce more cholesterol than can be obtained from an equal amount of butter. This is because margarine is full of trans-fatty acids, which are by-products of the hydrogenation process. Recent studies have shown that trans-fatty acids raise the risk of heart disease even more than do the saturated fats in meat and dairy products. In 1994 two Harvard scientists announced that “Transfatty acids are so dangerous they should be eliminated altogether. These fats contribute to 30,000 U.S. deaths from coronary heart disease each year.”

The only reason a person should select margarine over butter is if that individual is eating a strict vegetarian or kosher diet. Otherwise, margarine is a product that makes no sense.

CRÈME FRAÎCHE

This is a heavy, cultured cream with a delicate, tart flavor. Definitely not a weight-watcher’s food, crème fraîche can be made at home by whisking together equal parts of heavy cream and sour cream. Chill the mixture in the refrigerator for about 24 hours or until it is thick. Crème fraîche is delightful spooned over fresh fruit, mixed into vegetables, or added to salad dressings.

CREAM

Cream is the fat layer of whole milk. Commercial cream contains not less than 18 percent milk fat. It is separated from liquid milk and may be adjusted with added milk, dry milk, skim milk, concentrated skim milk, or nonfat dry milk. Cream, in all of its various forms, is a very high-fat food and should be used (if at all) in moderation.

HALF-AND-HALF

This is a mixture of cream and milk. Half-and-half contains not less than 10.5 percent milk fat, but less than 18 percent. It must be pasteurized or ultra-pasteurized. Homogenization is optional.

LIGHT CREAM

Light cream contains between 18 and 30 percent milk fat. It is pasteurized or ultra-pasteurized. Homogenization is optional.

LIGHT WHIPPING CREAM

Containing between 30 and 36 percent milk fat, whipping cream is typically ultra-pasteurized. Homogenization is optional. Whipping cream may contain additives, so read the label.

HEAVY CREAM

Heavy cream, also used for whipping, must contain at least 36 percent milk fat. It is pasteurized or ultra-pasteurized. Homogenization is optional.

SOUR CREAM

This is cream that has been pasteurized and cultured with Streptococcus lactis. Cultured sour cream contains not less than 18 percent milk fat.

CREAM CHEESE

This is a pasteurized cultured cream product. At 37 percent milk fat by weight, cream cheese is so high in fat and cholesterol that you can almost feel it pumping like thick sludge into your arteries as you eat it. You can eat it on bagels or just apply it directly to your hips and abdomen. Eat it once in a blue moon, but not more often.

ICE CREAM

Containing 10 percent or more milk fat by weight, ice cream is one of America’s favorite snack foods. However, many commercial brands contain artificial flavors, including some bizarre additives that are believed to cause health problems. Virtually all ice creams are loaded with refined sugar. Though you can obtain ice cream with unrefined sweeteners, from a nutritional standpoint it doesn’t matter much whether your ice cream is sweetened with honey or refined sugar. In either case, the product will still be high in fat and calories. Look for brands that use all-natural ingredients for flavoring, including fruits and nuts. You should definitely steer clear of artificial additives.

FROMAGE BLANC

A fresh spreadable cheese with a flavor between cheese and yogurt, fromage blanc has 36 milligrams of sodium, 20 calories, and just 0.05 grams of fat per ounce. By government standards, fromage blanc is a non-fat food.

CHEESE

One of the most popular foods in the world, cheese comes in more than two thousand varieties, many of them named after the locale from which they originated. Roquefort, France, is the village in which a cheese with visible veins of blue-green mold was first made. Stilton, England, and Gorgonzola, Italy, are both known for their distinguished cheeses.

Cheese is a fresh or matured product made by draining whey after coagulating casein, the primary milk protein. Various kinds of milk are used in cheese making. Skim milk is used to make cottage cheese, whole milk is used to make Cheddars, and a variety of cheeses are made from goat’s milk and sheep’s milk. The coagulation of milk casein is accomplished with milk-clotting enzymes, or by acid from microorganisms. The resulting curd is then cut, heated, drained, and salted.

Uncured cheese, such as cottage cheese, can be eaten right away. Ripened cheeses, however, are exposed to specific temperatures and degrees of humidity for varying periods of time. They are often further modified by the action of specific enzymes, yeasts, and molds to produce the specific desired characteristics and texture of the final product. With all of its subtle manipulations, cheese making is a highly sophisticated science. Cheese is the wine of milk products.

Cheese in the Diet

It can take as much as nine or ten pints of milk to make a single pound of cheese. This makes cheese a concentrated source of calcium, protein, vitamin A, and riboflavin. Unfortunately, this also makes cheese a concentrated source of fat and cholesterol. An ounce of Cheddar cheese has about 9 grams of saturated fat and contains about 110 calories. Because cheese is cured with a great deal of salt, it is also usually a concentrated source of sodium. Just one ounce of Cheddar cheese can contain 200 milligrams of sodium. Due to the high fat, cholesterol, and sodium value of most cheeses, cheese should be eaten in moderation rather than as a staple food.

Fat Labeling

Be observant of fat claims on cheeses. Just because a cheese label says “lower fat” or “reduced fat” does not mean that the actual fat content is low. These delineations mean only that the particular cheese product at hand is lower in fat than the original version. A Havarti cheese with its fat content reduced from 60 percent to 55 percent can be labeled “lower fat,” but it is still a high-fat food. Additionally, be wary of labels that read “made with part skim milk.” The cheese may also contain a high quantity of cream.

Even if a cheese is “lower fat,” a majority of the calories in that product will still come from fat. Gram for gram, fat contains twice the calories of protein or carbohydrates. More than 66 percent of the calories in a cheese with a 50 percent fat content will come from fat, most of which is saturated.

Look for the fat content on cheese labels whenever available, and remember that each gram of fat contains 9 calories.

Categories of Cheese

Semifirm Cheese These are dense and firm in texture. Cheddar, gruyère, and swiss are examples. These cheeses are good for melting.

Soft-ripened Cheeses These have a white crust on the exterior and ripen from the exterior to the interior. Soft-ripened cheeses should be ivory colored inside, with a smooth, buttery texture. If the crust develops an ammoniated scent, then the cheese is overripe and should be discarded. Brie and Camembert are the best known of the soft-ripened cheeses.

Semisoft Cheeses Similar to soft-ripened cheeses but firmer. Havarti, Provolone, and Edam are examples.

Double-Crèmes To qualify as a double-crème according to French law, a cheese must contain at least 60 percent butterfat. These cheeses are particularly smooth, creamy, and rich. There are many double-crème Bries.

Triple-Crèmes These cheeses contain at least 75 percent butterfat, making them the fattiest of all cheeses. Explorateur and St-André are the two best-known triple-crèmes. These cheeses are rich and creamy beyond compare, with a consistency close to that of pure butter.

Specialty and “Diet” Cheeses With an increasing awareness of fat, cholesterol, and sodium in the diet, consumers are looking for more healthful cheeses. Some lower-fat, reduced-sodium cheeses are available, including Lorraine Swiss, New Holland, and salt-free Gouda.

Grating Cheeses These are hard cheeses with a grainy texture. Romano cheese, made from sheep’s milk, and Parmesan are the best-known grating cheeses.

Blue-veined Cheeses The blue-green veining of cheeses is achieved by inoculating them with Penicillium molds, then storing the cheeses under controlled temperature and humidity. Roquefort cheese, ripened in caves in the otherwise barren Causses area in Aveyron, France, is the original blueveined cheese. Many cheese lovers consider Roquefort to be the finest cheese in the world. Unfortunately, Roquefort made for export has a higher salt content than the original variety. If you want a traditional Roquefort at its height of perfection, you’ll have to take a trip to France. Stilton, Bleu de Bresse, and Gorgonzola are other blue-veined cheeses.

Processed Cheeses These imposters are tinkered with by the liberal addition of salt, emulsifiers, lactic acid, preservatives, colorings, sugar, and other additives. Processed cheeses are typically very high in sodium. Avoid them. There is no reason to eat processed cheeses when real cheeses exist. Processed cheese is to real cheese what pressboard is to fine hardwood lumber.

Cottage Cheese

Cottage cheese has been a traditional favorite farm cheese because it is relatively easy to make and tastes delicious. The home kitchen method involves scalding skim milk and then letting it sit at room temperature for a couple of days until it sours. As souring occurs, whey separates from the curd. Boiling water is added to the pot, and the liquid is allowed to cool. With the curd settled and the whey separated, the mixture is poured through a cheesecloth and allowed to drain. The remaining dry curds are then mixed with a little cream and salt, and voila!—cottage cheese.

Commercial cottage cheese is made in much larger batches under controlled conditions. Culturing and direct acidification are the two methods used to settle the curd. Culturing involves adding Streptococcus lactis, Streptococcus cremoris, Leuconostoc citrovorum, and rennet to pasteurized milk. The milk is kept at 72°F for sixteen hours until the curd settles.

Acidification involves the addition of one or more acidifying agents, sometimes with additional enzymes, to pasteurized milk, to coagulate the curd. Cottage cheese is made by mixing dry curds with a pasteurized cream mixture. The finished product contains at least 4 percent milk fat. Low-fat cottage cheese is made in the same manner but has a milk fat content ranging from 0.5 to 2 percent.

Cheese Storage and Handling

Cheese should be refrigerated between 35° and 40°F for maximum freshness. Cut cheese should be tightly wrapped with plastic, waxed paper, or aluminum foil to keep it from drying out. Containers with locking seals are also good for storage, particularly for cheeses with strong odors, such as Limburger.

Hard cheeses such as Cheddar, Parmesan, and Swiss will keep for several weeks under refrigeration. Soft cheeses, however, such as Neufchâtel, Brie, ricotta, and Camembert are highly perishable and should be used within a few days of purchase.

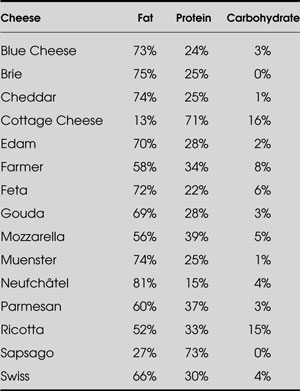

Caloric Values of Cheese

The calories from cheese come from fat, protein, and carbohydrates. The following list shows the percentage of calories obtained from each of these sources in fifteen different cheeses. Note that the percentage of total calories obtained from a source is not the same as the percentage of that source in the product. In other words, a cheese may be 50 percent fat by weight, but almost 70 percent of its calories may come from fat.

Most cheeses can be frozen. If you freeze cheese, seal it in a moisture-proof container to prevent dehydration. Some cheeses, especially the blue-veined cheeses, become crumbly after freezing and thawing.

With the exceptions of cottage cheese, cream cheese, and Neufchâtel, which should be served cold, cheeses are best served at room temperature. This allows for full aroma and flavor.

EGGS

Philosophers have banged their heads in vain over the age-old question: which came first, the chicken or the egg? While we may never know the answer to that brain-teaser, we do know that eggs have stirred up more than just philosophical controversy. In recent years, eggs have come under fire because of their cholesterol value, their possible contamination by salmonella bacteria, and the manner in which egg-laying chickens are raised, including the heavy use of drugs.

Taking Eggs to Heart

Eggs are concentrated nutrition. A whole egg has 6 grams of protein, 5.6 grams of fat, and about 270 milligrams of cholesterol. The amount of cholesterol in eggs has hurt the reputation of this food, for good reason. Dietary cholesterol is linked to arteriosclerosis and heart disease, including heart attack. A single egg contains more than 25 percent of the amount of cholesterol produced by the body daily. This is a significant amount of added cholesterol.

The American Egg Board has fought back against the cholesterol issue by pointing out that our bodies need cholesterol. This is true, but we manufacture as much cholesterol as we need. There is no evidence whatsoever that extra dietary cholesterol is beneficial in any way. There are many studies, however, that link dietary cholesterol to cardiovascular disease.

Bad Bacteria

In 1989 the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued a warning that eggs may contain salmonella bacteria. The USDA urged consumers to refrain from eating raw eggs in any form and recommended the thorough cooking of all eggs. The danger was apparently due to salmonella-contaminated breeding stock. Salmonella bacteria have previously been detected on the shells of some eggs, but this poses no real health hazard. If a shell is cleaned, the egg can be cracked and used without concern. There is some evidence now, however, that a small percentage of eggs may actually contain salmonella bacteria inside their shells. Thus, it is important to cook eggs thoroughly, for a minimum of 3 minutes. Forget about 1-minute eggs, or eggs sunny side up with runny yolks. For safety’s sake, avoid runny yolks.

Low-Cholesterol Eggs?

The American Heart Association recommends that Americans consume no more than 300 milligrams of dietary cholesterol per day. That’s bad news for egg producers, because a single egg can contain anywhere from 210 to 275 milligrams of cholesterol. That’s over twice the amount of cholesterol in two 4-ounce pork chops.

Because of public concern about cholesterol in eggs, industry sales have plunged from $4.1 billion in 1984 to $3.1 billion in 1989. To combat the sales slump, egg producers are attempting to manipulate the dietary intake of their chickens to produce a lower-cholesterol egg. Some producers say they have already accomplished this.

The federal standard for cholesterol in a Grade A large egg is currently 274 milligrams of cholesterol. A few commercial hatcheries in Pennsylvania have been marketing their eggs as lower in cholesterol than the federal standard, claiming that their eggs contain between 185 and 210 milligrams of cholesterol. The difference, they say, is due to a secret feed formula.

But are there really low-cholesterol eggs, or is the federal standard simply higher than the average cholesterol value of most eggs? According to a year-long study conducted by the Department of Agriculture and the Egg Nutrition Center in Washington, both regular eggs and those labeled “low cholesterol” actually contain the same amount of cholesterol. The eggs sampled contained between 210 and 230 milligrams of cholesterol apiece, regardless of how they were grown.

Chickens on Drugs: Just Say Cock-a-Doodle-Doo

Although some chickens are raised in hen houses in which they have the run of the floor area, many egg-laying chickens are housed in cramped cages in which their movement is severely restricted. The cage system is favored for its efficiency as far as egg production is concerned, but is highly criticized as inhumane. In today’s egg-laying facilities, light, temperature, and humidity are carefully controlled. The hens live in windowless, insulated, force-ventilated housing, with an artificial day/night light cycle designed to stimulate egg production. Caged birds are suspended over troughs that catch their fecal droppings. In these crowded conditions the hens exhibit cannibalistic tendencies. To combat this, their beaks are clipped by a machine that cauterizes the beak.

The egg industry claims that such housing actually protects the chickens from the elements, disease, and predators.This rationale is so thin that no further comment is needed. In these cramped, unnatural conditions the hens are fed rations that typically contain antioxidant preservatives, mold inhibitors, and antibiotics. Antibiotics are particularly important, because in such close living quarters chickens can easily spread disease. Chickens are fed such a high quantity of antibiotics that the drugs pass into the feces, which discourages flies from breeding in the waste. Chicken feed may be contaminated with high levels of pesticides, but these residues most often go undetected because of lack of feed testing. Some of the chemicals in chicken feed wind up in the eggs.

Making the Grade

Eggs are graded and sized according to the quality of the egg and its shell, and the size at the time of packing.

Grade AA eggs stand up tall when cracked. They have firm, stand-up yolks. The area covered by the white is small. There is more thick white than thin white. These eggs are sometimes labeled “Fresh Fancy.”

Grade A eggs are just a little less firm than Grade AA. The yolk is still thick and upstanding, and there is more thick white than thin white.

Grade B eggs are thinner and spread out more. Their yolks tend to be flat, and there are about equal parts thick white and thin white.

Egg Sizes Based on Net Weight Per Dozen

| Jumbo: | 30 oz per dozen |

| Extra Large: | 27 oz per dozen |

| Large: | 24 oz per dozen |

| Medium: | 21 oz per dozen |

| Small: | 18 oz per dozen |

| Pee Wee: | 15 oz per dozen |

Fertile Eggs

Fertile eggs are from chickens that have had sex. So at the very least, the hens are happier than their sexstarved counterparts at most commercial hatcheries. If allowed, a fertile egg will hatch, whereas a non-fertile egg will not. Beyond this fact, there appears to be no nutritional difference between fertile and non-fertile eggs. Fertile eggs contain a small amount of male hormone.

Brown Eggs vs. White Eggs

Despite the fact that brown foods just look more natural than white foods, there is no qualitative difference between white-shelled and brown-shelled eggs. Shell color is due to different breeds of hens. If feed rations between breeds are the same, there will be no nutritional difference in the eggs.

Eggs in the Diet

Because eggs are a good source of protein, they can be of value in a healthy diet. Unless you suffer from high blood cholesterol or some form of cardiovascular disease, you can most likely eat as many as three eggs per week. With eggs, as with other highcholesterol foods, the key is moderation.

Sunny, Runny, and Raw

Perhaps you like your eggs sunny side up with a runny yolk. Or maybe you are used to tossing a fresh, raw egg into a blender to make a protein shake. Or maybe you just like hollandaise sauce. Think again. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, salmonella contamination of eggs is a problem. It is unwise, and potentially unsafe, to eat raw eggs and raw egg products. Additionally, raw eggs contain avidin (part of the egg protein), which inhibits the absorption of biotin, one of the B vitamins. Cooking eggs thoroughly inactivates avidin.