CHAPTER FOUR Do You Believe in Magic?

Life is like a game of cards. The hand that is dealt you represents determinism; the way you play it is free will.

—Jawaharlal Nehru

Do you remember when you first fell in love? Not the boy or girl, but the moment? You know, that “Wait… what?” shock of a feeling when you’re suddenly slapped in the face and you’re wide-awake like you’ve never been before?

Man, the first time I ever felt that, I wasn’t looking at a girl or a boy. I was looking at some close-up magic, and the effect was instantaneous: I was in love. And magic has been the perfect balance, the perfect complement, the perfect escape, the perfect icebreaker, the perfect thing to separate me from the crowd ever since. From that moment on, magic wasn’t a hobby. It wasn’t band camp or chess club. Magic was mine and, in it, I found myself.

Shortly after moving to Garden Grove, California, to start seventh grade in 1993, I headed back to Washington state for a Little League all-star tournament. I was looking forward to seeing my old friends for the weekend, but I can’t say I was excited. It was hard for me to get excited about anything. In California, I hadn’t yet made any friends. See, I knew something other kids didn’t know; I knew about loss, and I knew that there was evil in the world. It made it kind of hard to just be. I’d changed my scenery, but to me, I was still the kid who knew too much. True joyousness requires suspending disbelief, right? You’ve got to be fully in the moment to bask in it. I wasn’t sad so much as I was having trouble finding my joy.

That weekend, I stayed with my old Little League all-star coach, Coach Bob Schmidt, and his family. They invited their sixteen-year-old neighbor, Michael Groves, over to the house to show off some magic tricks. In their living room, Michael did about thirty minutes right in front of me, and Coach Schmidt videotaped the whole thing. Right there on VHS, you can see my life change.

Michael Groves did card tricks, he made sponge balls appear and disappear from his hands, he lit a match and, when he looked at it, the flame shot up twenty feet as if out of a cannon. I was the perfect audience member, eyes bugging out in astonishment. It was a drastic excitement, the polar opposite of what I had been feeling for the last year.

Michael pretended to be struggling—the old bait and switch. He kept screwing up a trick, reeling me in and reeling me in. I was feeling bad for him. When he pulled it off—BOOM! I was hooked. I thought he’d been messing up. He wasn’t; he was making me care.

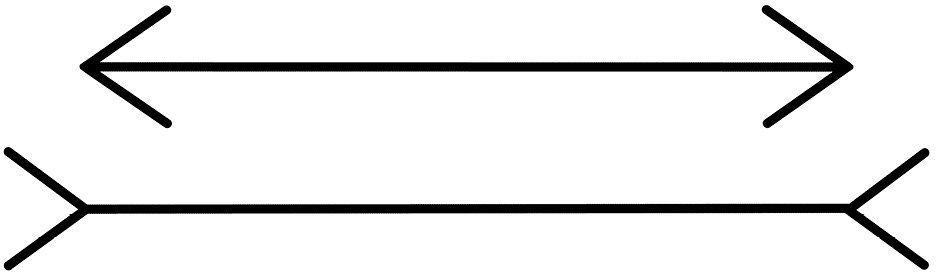

To me, that’s what magic is. It has nothing to do with pulling rabbits out of hats or pretending to saw dancing girls in half. On a very practical level, magic is the art of taking advantage of how much you trust your own visual sense. Most people will believe only what they see with their own eyes. Magicians, however, know that our visual experiences are far less reliable than we think. For example, take a look at what is known as the Müller-Lyer illusion:

The top line is shorter than the bottom, right? Think again. They’re exactly the same length. People often fail to see things—even when staring right at them. Many of our perceptions are, to one degree or another, illusions. My job as a magician is to exploit your illusions by misdirecting your attention, making sure you’re not seeing what I don’t want you to see.

That’s the technical part of magic. It’s what we practice ten thousand hours to master. But real magic is being made to care, being taken to a place where everything else in your life fades away and you’re invested in this story unfolding before you. Think about it: I was a scared, worried, thirteen-year-old kid; now I was given something to be joyous about. Maybe, if Michael Groves played the guitar, my jaw would have hit the floor over his rendition of “Amie” by Pure Prairie League. (Hey, it was the early nineties… every guitar player did a rendition of “Amie.”) But at the exact moment I needed it, I saw a magic trick and was transported. Because there’s something magical about magic.

The great ones get it. David Copperfield, Ricky Jay, Bill Malone. They don’t do tricks; they create a sense of wonder. When you’re making magic, there’s nothing better than hearing an audience member’s sudden intake of breath, shock mixing with delight at exactly the right moment.

That’s what we’re after, an insight confirmed for me not long ago, after my buddy Paul Tessier and his wife, Natalie, had twins, a boy and a girl, Cade and Kara. I rented a Duffy boat and took his kids, who were all of maybe one year old, for a spin around Newport harbor. I’ll never forget holding Cade as his hands reached out and felt the ocean for the first time. He was transfixed, gingerly touching the water and staring so intently at this awe-inspiring sight before him. I remember realizing there are so many “firsts” we’re never aware of: first steps, first words. Cade will never remember the first time he touched the ocean, but I recognized what I witnessed him experience: that sense of pure awareness, of childlike wonder. It’s what every magician is intent on delivering. It also happens to be, as I learned in therapy, what life’s all about: figuring out ways to empty out our cluttered minds and get back to that place where we innocently discover things as if for the first time.

I suspect that, seeing my excitement, Coach Schmidt and his wife took Michael Groves aside and said, “Listen. This kid is really screwed up. You think you could come with us to the magic store?” Because, the next day, that’s what happened. We went into Seattle; walking into that magic store was like exploring a new world. I bought my first magic book, Modern Coin Magic, by J. B. Bobo, one of the fathers of coin tricks. And I bought a mini deck of cards—ten in all—and used that to practice my first-ever card tricks.

I was hooked, man. Back in California, my room was no longer a sad, solitary place. It was magical. I spent hours—I mean, hours—learning a lot of useless moves from the J. B. Bobo book, back palms and coin flips that I’d never end up using. I spent hours shuffling and reshuffling decks and learning tricks.

Even today, the most soothing sound in the world to me is the rippling swoosh of a deck of cards in shuffle. I’ve had times in my life where I’ve felt crushingly alone, at a deeper level than most people will ever feel. But once I started shuffling, I was okay with being alone. And then shuffling made me realize I wasn’t alone, not as long as I had a deck of cards in my hands. Cards have never let me down. They’ve always been there for me. For years, when I’ve had a big decision to make—what team to sign with, say—I go somewhere quiet and shuffle, emptying my mind for hours. After which—magically—my decision comes to me. My fifty-two buddies never lie to me and always tell me when I’m wrong.

Today, there are instructional DVDs, and it’s easy to learn a move when you can see it. But when I was thirteen years old, you had to learn by reading. Try following this instruction: “Take right forefinger 260 degrees, turn right over left wrist. Keep left index at 12 degrees, and hit interior pinky.” Dude, that is hard. I would read something for a week and I still wouldn’t be able to do the trick.

Making matters worse, most instructional books were written for right-handers. I’m a lefty. Which meant that every time I saw the word “right” I had to tell myself “left”—and my reading comprehension wasn’t too good to begin with.

What kept drawing me back? When I would go into that magic world, I didn’t think about anything else in life. Nothing. It didn’t matter how sorry I was feeling for myself. There was no voice in my head saying, My mom’s gone, my dad’s in prison. Nothing. I didn’t think of any of that. I just literally got lost in entertaining myself. That’s when I first started visualizing things, something that would help me on the football field and in all aspects of life; I’d close my eyes and see my hands, completing a trick. Magic showed me that no matter how difficult something is—because, let me tell you, it was really freakin’ hard to learn—you can do it if you believe. You know the one thing the person who believes he can has in common with the person who thinks he can’t? They’re both right.

In addition to losing myself in this newfound joy, I was driven by the shame of what my father had done. To many, especially in the Seattle area, the Dorenbos name was synonymous with a horrendous, evil act. I was going to do something that restored pride to the name. That’s why I’d dream of starring on the baseball field in the Kingdome and of performing sleight of hand before adoring crowds. Besides the sheer rush of it, I wanted to give Randy, Krissy, Aunt Susan, and Nonnie and Poppy something to be proud of.

Susan noticed this new passion of mine—how could you not? That’s when she asked Ken Sands, an ex-boyfriend of a friend of hers, to come over and meet me. He owned Magic Galore & More, a magic store in Orange County. He stopped by our condo one night with a deck of cards. He did a few tricks for my aunt and me, and my jaw must have hit the floor again. When he put a three of clubs on the kitchen table, turned it facedown, and then turned it back over… and it had changed to a six of diamonds, I was catapulted out of my chair and went running around the house, screaming like Linda Blair in The Exorcist… Are you kidding me right now?

“Ken!” I said, breathless. “Michael Groves did the same trick! He turned a card over and then it changed!”

If you think back on your life, it’s full of influences, right? Some people call them spirit guides, others call them mentors, or even coaches. They’re people without whom you likely would have been lost. They’re people who teach you not only a skill set, but values, too. Beginning that night, Ken Sands became my first coach.

Ken was in his thirties at the time, with a dark curly mullet pulled back into a ponytail. He was super chill and really quick-witted—in person and while performing. I didn’t know it at the time—how could I?—but I found out later that Ken had been having his own troubles when he met me. He’d divorced and had been battling depression. He’d had thoughts of taking his own life. Now he had this wide-eyed kid focused on him like a laser beam.

You never know the impact you might have. I knew I needed him. But later in life, Ken told me that he needed me back then. In the same way that studying magic took me out of my head, shutting down that soundtrack of victimhood, teaching magic to me took Ken out of his head.

Ken had something called an answering machine. That was this thing back then, in those pre–cell phone, e-mail, and voice mail days, on which you’d leave a tape-recorded message for someone if they weren’t home. Because, kids, as strange as this sounds, at one time in America you weren’t able to reach everyone you wanted to at exactly the moment you needed them.

A couple of years ago, Ken told me: “Man, you were like that Glenn Close character in Fatal Attraction—‘I will not be ignored!’ ” he said. He’d come home and find twenty-one messages from me on his answering machine. Meantime, I’d be waiting by the phone in Susan’s condo, counting the minutes until he called back.

I’d spend hours in Ken’s magic store. He was always teaching me, but in subtle ways—like any good coach. He wouldn’t show me a trick; he’d challenge me to figure it out. He never said the words “you have to earn it,” but that’s what I felt: I needed to prove to him that I was worthy of the secrets. He’d tell me to work on a trick—“The next time I see you, I’ll observe where you are.”

What I heard was a challenge. I’d think to myself, I need to show him I’m motivated. I need to show him I’m worthy. I need to show him something he doesn’t expect from me. I wanted to make him proud of me, and prove he’d made the right decision in mentoring me.

Damned if, years later, those weren’t the exact same thoughts running through my brain doing drills during practice on Andy Reid’s Philadelphia Eagles. X-and-O’ing plays, just like devising intricate card tricks, ain’t what coaching is really about. Getting guys to run through brick walls for you—that’s the secret to coaching. And that’s what Ken Sands did for me: He made me want to prove to him every single day that I could do this thing.

There’s this move, it’s called a hotshot cut. It’s a one-hand cut of the deck in which you end up shooting a card like a missile from the middle of it. I saw David Blaine do it on TV. Ken showed it to me. I spent hours on the hotshot cut; to this day, I can’t do it. But here’s the thing: in playing around with it for hours, I discovered I could shoot a card real smoothly off the top of the deck instead of from the middle. I figured out that I could mask it so it looked like the card was coming from the middle. It was a much cleaner way to do the hotshot cut than the traditional way. I’d found a way to actually cut the cards and shoot a card out of it. It wasn’t the hotshot cut; it was even better… the Dorenbos Cut.

Susan dropped me off at Ken’s store, and I remember running in, all breathless and sweaty. “Ken, Ken, Ken,” I stammered, gasping. “Check this out, check this out. I put a card in the middle and then I can cut to it from the center so it’s on top and I can shoot it out and catch it, like this!” The card went flying up and back down in a straight line.

I remember Ken doing a double take. “Wait, show me that again,” he said. This was me, discovering a way to improve a move. And it was mine, all mine—nobody else was doing it this way. I remember Ken smiling and shaking his head in wonder, like, Holy shit. Maybe this kid has got something.

Around this time, I saw the greatest freakin’ trick of all time. I was sitting cross-legged on the floor of Susan’s living room, inches from the screen of the twenty-seven-inch TV, watching David Copperfield’s prime-time special Fires of Passion. He brings a woman from the audience—Tess—onstage and sits her on a stool. He explains that when he was a tiny little boy, he wore sneakers that he calls his “Air Coppers.” He shows the crowd this tiny baby shoe and then puts it in his back pocket. When he was a baby magician, he says, he would make his friends’ rings disappear—only to reappear tied to the laces of his Air Coppers. He asks Tess for her ring. It’s a gold panda coin ring, and ripping one-liners that have the audience in stitches, Copperfield makes it disappear without his hands ever leaving his side or Tess’s view. Sure enough, he turns around and the ring is tied to the lace of the shoe in his back pocket.

What the…? To this day, it’s the most amazing trick I’ve ever seen. I just loved the whole premise, and the interaction David had with Tess. And the fact that before this trick, no one had ever heard of a freakin’ panda ring before, and now there are magic geeks across the globe trying to collect them. I loved that trick so much as a kid that a few years ago, I put out a public call on my website for someone—anyone—who could get me an invite to Copperfield’s private warehouse. I just wanted to hold that little baby shoe in my hands. Sure enough, not long ago, it happened, and I get teary-eyed whenever I think about it. This dude, Mike Michaels, who helped me set up a trick in my act, had seen what I’d written on my website.

“Hey, I’m friends with Dave, we’re going to get you into his warehouse,” he said.

So there I was, in February of 2018, in David Copperfield’s sixty-thousand-square-foot Vegas warehouse at 11:30 at night. A magic freak’s wet dream, with hundreds of millions of dollars of memorabilia, including just about everything Harry Houdini ever owned. Dave only takes four to eight people through at a time, doing tricks and telling stories all the while. He describes his visits as an aspiring magician to Tannen’s Magic Shop in New York City back in the day, and he re-creates the first trick he ever saw there… and you’re really there: he’s transported the store into his warehouse. Here’s the original counter, and on it sits the original cash register. What a trip. By the time we get to the Air Coppers, I’m a blubbering mess. Why was this so emotional for me? Because it drew a direct line to that scared kid with a bursting heart in front of that TV at Aunt Susan’s. Magic brought that kid from there along to here. I was crying because thanks to magic, that kid—with all his wonder—was still… me.

What are the odds that a thirteen-year-old aspiring magician would one day be standing in front of David Copperfield for a late-night close-up magic-show booty call? The only way to explain it is to buy into the old adage If you believe it, you can achieve it. I think about that kid who followed tragedy by getting lost in the world of magic, and I know that he was doing exactly what actor Will Smith is talking about when he inspires others by explaining the secret of his success. “You don’t try to build a wall, you don’t set out to build a wall,” Smith has said. “You don’t say ‘I’m gonna build the biggest baddest wall that’s ever been built.’ You say, ‘I’m gonna lay this brick, as perfectly as a brick can be laid,’ and you do that every single day, and soon you have a wall. It’s difficult to take the first step when you look at how big the task is. The task is never huge to me, it’s always one brick.”

That’s some deep advice, right there. And it was what I was doing each time I sought out Ken for advice or feedback over the most minor of moves. I was laying brick upon brick, man.

By the time my eighth-grade talent show rolled around, I’d become obsessed with another Copperfield trick. He’d take a piece of paper and make it float all around him; then he’d unfold it, and it would suddenly have been transformed into the shape of a rose. He’d levitate it again, before lighting it on fire… and out of the flames, he’d produce a real rose. No shit—an actual rose. I told Ken I had to learn this trick for the talent show.

Ken told me the trick had actually been created by a magician named Kevin James, who had a VHS instructional tape on the market. Aunt Susan bought it for me, but Ken had warned both of us: the floating-rose trick was dangerous. It involved fire and flash paper. I remember the word “flammable” was spoken. Aunt Susan said I could work on the trick, but only when she was in the house.

Well, that lasted about two weeks. Home alone, I singed a twelve-by-twelve patch of the living room carpet black. When Susan got home she was kinda pissed—especially when I lamely tried to blame Krissy for it. Finally, I relented and copped to the crime. How cool was Susan, though? “Let me give you some advice,” she said. “If I’d have done this, Nonnie would have freaked out. So here’s what I would have done. I’d have taken a pair of tweezers and pulled up each little piece of carpet. Just give it a haircut. Just enough to take off the singed top. If you had done that, I never would have even noticed.”

Now that’s a parenting lesson, right there. She may have grounded me, but she also got across that she was on my side. And it wasn’t the end of the world. Remember what I said about coaching? How it’s really about getting guys to run through brick walls for you? Susan was a coach.

Our eighth-grade talent show had some dudes lip-synching Boyz II Men’s “I’ll Make Love to You” and another group doing air guitar to Ace of Base’s “The Sign.” Heather Wallace and Erin Dodd sang “The Rose” by Bette Midler, and they nailed it. Well, here I come, galloping up onstage. By now, I was an awkward man-child, towering over my classmates at six feet tall. I’d grown my hair long and had shaved it on the sides; in the back, I had a ponytail. And I was wearing a silk shirt tucked into black slacks—’cause magicians have long hair and wear silk shirts, right? Oh, yeah, I also had both ears pierced. Yep. Killin’ it.

I came onstage to the tune of “Return to Innocence” by Enigma, kind of my theme song:

Don’t care what people say

Follow just your own way

Don’t give up, don’t give up

To return, to return to innocence

I’d once been afraid to be seen as different—the kid whose dad killed his mom—but now I was embracing standing out. No one else was into magic, no one else had this kind of mulletlike hairdo—yet—no one else was quite so tall. But it was all good, because, every day, magic brought me a sense of wonder and obsession—much to my teachers’ chagrin, especially when the sounds of my shuffling a deck of cards interrupted quiet reading time in the classroom. Magic really was my return to innocence.

So I walked out onstage with a candle. It was dead quiet; I could hear the stage floor creak underneath my feet. The music kicked in and I lit the candle, took the paper out, folded it up, and sure enough… it started floating around me. It floated over to my index finger; I snapped, and it landed perfectly in my hand. I unfolded it and, amazingly, it was in the shape of a rose.

Now I held the candle to the paper rose floating in front of me. I lit that bitch on fire, causing a huge, bright flame to explode. And now, the climax: once the flame disappeared, there in its place was… a real muthafuckin’ rose. Excuse my language, but c’mon: that’s what it was, a real muthafuckin’ rose.

As cool as that sounds, there was dead silence in the auditorium. Shit, I blew it, I thought. They saw how I did it. But then, after that nanosecond of stunned silence, there was a roar and the audience was out of their chairs, cheering and stomping their feet. What a rush, man.

I won the grand prize—a twenty-five-dollar gift certificate to Soup Plantation. Yeah, that’s what I’m talkin’ ’bout. Liv-in’ large. Ken was in the audience, and afterward we dissected everything about my performance. It was an early lesson in underpromising and overdelivering. The audience wasn’t expecting a thirteen-year-old to walk out onstage and pull off a David Copperfield trick. “I think you stunned them for a moment,” Ken said, explaining the silence that initially met my reveal of the rose.

What an adrenaline rush. Until then, I’d been addicted to the challenge of learning tricks. Now I’d felt the thrill of performing. I was hooked. And it wasn’t just the adoration from the crowd that drew me in. It was also the surge of energy you feel working without a net. Unlike a card trick that goes bad, there’s no covering up a mistake when lighting a floating rose on fire. If you screw up, you look like a dumbass. That’s either terrifying or something to lean into—and I loved leaning into it the first time I took the stage. It was what I’d go through years later when snapping on a football field. They might not know who the hell you are, but all eyes are on you. And it’s do or die. Do it, or go home. Well, let’s go.

I started to study what made for successful performances. I spent hours watching Bill Malone on The World’s Greatest Magic TV special. It was an annual Vegas gig of countless magicians that was taped and shown on TV. Bill Malone was the featured card guy. And he was everything I wanted to be as a performer. He wasn’t some cool dude with wavy hair who wanted you to believe he had real magical powers. No, Bill Malone was all about having fun in the moment. He was a quirky-looking dude who audience members would yell out to, and he’d hit ’em back with classic one-liners. It was nonstop fun, and that’s how I longed to present myself. I was a fan of David Blaine, but I had no interest in being him—or anyone else, for that matter. I wasn’t about to levitate in the middle of Times Square or push over a palm tree in Vegas with my finger. But what I could do… was bring you along for a great, fun, laughter-filled ride.

One day, while I was working all this out, I had an aha moment. Naturally, I couldn’t wait to share it with Ken. This was so big I had to tell him in person. At the store, I could barely stop the words from streaming out of my mouth.

“Ken, I’ve figured it out,” I said. “I’ve got the secret of magic.”

His eyes narrowed. Here we go again, he must have thought. More grandiose thoughts.

“You can never screw up,” I said.

“What?” he asked, a little exasperated. After all, there were probably some paying customers in the store.

“In magic, you can never screw up,” I repeated. “It doesn’t matter what we do, as long as the audience is entertained. You can’t mess up if the audience doesn’t know you messed up, and what does that mean, Ken? It means the whole thing is about the audience. It’s not about us, or the trick. We spend all this time routining everything and we forget to see things from the audience’s point of view.”

Now, that may not sound like some grand epiphany. But it made me realize that magic was just the tool for me to connect to people. I could get in front of ten thousand people and the same move could either get a golf clap or a standing ovation—and the difference between the two had to do with our relationship, the audience and me.

It was truly eye-opening, and, I’d learn later, it extends to all aspects of life. Everything really is about relationships. How you treat people is how you’ll be treated. Put the audience first, show them love, and you’ll get love back. Screw getting up and just doing a collection of tricks. Tell an ongoing, openhearted story, and you feel the love, in life and magic.

That’s what I learned in seventh and eighth grades as magic brought me out of my shell. Now, what to do with all that pent-up energy I’d been tamping down ever since Dad killed Mom?

Well, that’s where football comes in. Magic had transported me. Now it was time for football to let loose on the world all of the emotions I’d been keeping way down inside.