CHAPTER 9

HOW TO OUTSMART INJURIES

Back in 2002 I developed a case of patellofemoral pain syndrome, or runner’s knee, that plagued me for more than three years before I was able to silence the pain it caused and return to normal training. As frustrating as it was to lose three of my prime running years (I was thirty when the injury struck), I don’t regret the experience, because in overcoming the breakdown I developed the brain training method of injury prevention, which has helped me stay injury-free ever since, and will help you, too.

It began as a dull pain under my right kneecap, which first manifested itself in early November, when I was beginning to log some heavy miles in preparation for the Boston Marathon the following April. As with most overuse injuries, it introduced itself as a mild, local ache that emerged after five or ten minutes of running and went away as soon as I completed my workout. Like all too many competitive runners, I stubbornly continued to increase my running volume despite the pain, and as a result it became increasingly severe during my runs and lingered increasingly longer afterward. Eventually, even everyday activities became painful.

The wheels came off during a planned 16-mile endurance run. My right knee was tender from the first stride and became steadily worse. I kept running. By the time I reached the midpoint of my route the pain had become so intense that I began to fear I would never run again if I did not stop, so at last I pulled up. I was eight miles from my apartment in either direction. It was a long, agonizing, despondent walk home.

Running was impossible for the next few days. When mere walking was no longer painful I tried to resume running, but the pain quickly returned, so I backed off again and tried other treatments, turning to bicycling to keep fit. These other treatments included icing, which gave me only temporary relief, and acupuncture, which did as much good as lighting money on fire would have done. I persisted in believing that if I just gave the knee enough time to heal, and then eased carefully back into running, I’d be cured without ever having to know exactly what I was cured of or what had caused the injury. But after completing two full trips around the same circle of resting and then dipping my toes back into training, only to feel the knee degenerate all over again, I decided I needed to see an orthopedist.

The orthopedist first prescribed conservative measures: knee taping, anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy. None of these measures helped, so he scheduled me for arthroscopic surgery. During the surgery he found some fissured cartilage—a condition called chondromalacia—that might have been the cause of my pain, so he filed it down to make it smooth. When I recovered and resumed running, the knee degenerated yet again. Another magic bullet had missed its mark.

I never did find a magic-bullet cure for my injury. Instead, I pieced together a “cure puzzle” by finding individual measures that helped a little and accumulating them until, almost surprisingly, I had made a complete comeback. As I progressed through the long process of trying everything, discarding things that didn’t work and retaining things that seemed to help my knee, if only a little, I began to make slow, almost imperceptible progress. At last, some forty months after that abandoned 16-miler, I was able to complete an entire marathon and declared myself officially cured.

What were the particular pieces of my cure puzzle? Strength exercises that improved the stability of my hips during running represented one piece. A few small gait modifications—including tilting forward to correct a problem of overstriding—provided another. Switching to a pair of minimalist running shoes that allowed my feet to enjoy more freedom of movement turned out to be a third piece.

These corrective measures shared one common characteristic that I only observed in retrospect, after I learned more about how the brain controls the running stride: They allowed me to run more naturally. The strength exercises corrected muscle imbalances caused by my normal but unnatural lifestyle of spending most of each day sitting in chairs. The gait modifications corrected stride flaws that are caused by the historically unnatural act of running while wearing shoes. And my change of shoes also helped me run in a more barefoot-like manner.

The final piece of my knee cure puzzle was a zero-tolerance pain policy that I adopted during the cautious, yearlong training ramp-up that culminated in my comeback marathon. The reason the injury became as severe as it did in the beginning was that I tried to run through my knee pain instead of reducing my running in response to it. And one of the main reasons it took me so long to overcome the injury was that I kept on reacting to pain too slowly in each new attempt to resume normal training. Instead of cutting back again at the first hint of soreness, I waited until the pain was at least moderate. Sure, by doing so I was able to squeeze in a few more workouts before having to take time off again, but I had to skip many more workouts than I would have missed if I had reacted to pain (by backing off my running) with a hair trigger.

In that final, successful return to full training I made a commitment to stop running as soon as I felt the least soreness in my knee (or pain anywhere else, for that matter) and to resume running only when I could at least start the workout pain-free. The plan was to run as often and as far as I could run without any pain, no matter how frequently I had to abandon workouts and take extra days off and no matter how frustrated I got by the regularity of these setbacks. When I began to execute this plan I found that the setbacks were indeed frequent and the frustration was, at times, almost unbearable, but I stayed the course. As a result, my progress was decidedly of the two-steps-forward-one-step-back variety, but it was progress nevertheless. It took many weeks to advance from 20 miles a week to 30, and from 30 to 40, and eventually I hit a hard limit at roughly 60 miles per week. As exasperating as this process often was, the only alternatives were quitting completely and the old cycle of rushing ahead and breaking down, so I celebrated it.

The journey was much longer than I would have preferred, but taking the slow route was the very thing that allowed me to eventually reach my coveted destination of being able to train for and complete marathons. Best of all, I am confident that because of everything I learned in dealing with my knee injury, I will never suffer another major overuse injury. In fact, this experience left me convinced that nearly every running injury is preventable. Behind the particulars of the methods I developed to beat my knee pain is a general injury-prevention strategy that, if practiced faithfully, can drastically reduce any runner’s risk of developing any type of running-related overuse injury. The two core tenets of this strategy are as follows:

1. Run more naturally.

2. Never run in pain.

If you do these two simple things you will outsmart potential injuries virtually every time.

As you might expect, the brain is at the center of both tenets of this injury-prevention strategy. The concept of running naturally is based on the understanding that the brain’s motor centers store preferred stride patterns that the body is not always able to properly execute for one reason or another; that this failure is a major cause of many running injuries; and that reactivating one’s natural, preferred stride patterns will prevent injuries. And pain is your subconscious brain’s way of telling your conscious mind that running is damaging tissues in a particular area of your body and therefore you need to stop running and/or change how you run. It’s amazing how often we runners act as if this fact were not perfectly obvious, and how much more healthily we can run when we begin listening to our subconscious brain’s warnings.

WHY RUNNING INJURIES AREN’ T NATURAL

In a widely publicized article published in the journal Nature, Dennis Bramble of the University of Utah and Daniel Lieberman of Harvard University argued that running was a key factor in the evolution of human beings from earlier hominid species. Most discussions of early human evolution focus on the brain. The growth and development of this organ in our immediate genetic ancestors is generally considered to be the pivotal factor in the emergence of humanity. The burgeoning brainpower of the last prehumans allowed them to create better and better tools and more and more sophisticated ways of cooperating with each other to increase their chances of survival on the African plains. But according to Bramble and Lieberman, changes from the neck down were no less critical than those that happened inside the skull. And the most important factor driving these changes may have been a selective pressure toward becoming better endurance runners.

Bramble and Lieberman pointed to the many changes in physiology that made us better runners as we evolved away from the tree apes, including the development of upright posture, longer legs, more rigid feet, and bigger buttocks. In addition, our loss of body hair and the development of one of the most effective sweating mechanisms in the entire animal kingdom gave us a tremendous capacity to maintain a safe body temperature while running for long stretches on the sun-baked African savanna. These changes are believed to have given us the ability to hunt down and kill prey, such as antelope, that were much faster over short distances but tired out quickly, as all sprint specialists do.

When I read this article, I bought into the argument immediately. But almost as quickly I found myself asking an obvious question: If humans are naturally engineered to run, why are running injuries so common? Surveys estimate that more than half of runners suffer at least one injury per year that’s serious enough to interrupt training—an injury rate that rivals that of tackle football. You would expect a species to demonstrate far greater durability in a pursuit for which it is genetically designed.

As a longtime student of the sport of running, and of running injuries, I was able to answer my own question. I concluded that the epidemic frequency of running injuries is due to the fact that our modern lifestyle, in relation to running, is unlike the lifestyle of our primitive ancestors in two key ways—we spend most of our nonrunning time sitting in chairs and seats, and when we do run, we wear shoes—and that these two factors cause us to run unnaturally, resulting in injuries.

HOW SITTING CAUSES RUNNING INJURIES

The average office worker spends almost nine and a half hours of each weekday sitting. The most notorious consequence of sitting too much and moving around too little is weight gain. One study found that men and women who spend more than seven hours of each day sitting are nearly 70 percent more likely to be overweight than those who spend less than five hours sitting.

There’s another major health consequence of excessive sitting that you don’t hear much about: muscle imbalances. Over time, spending hours of every day curled up in a seated position causes some muscles to become abnormally tight and weak and others to become just plain weak. Such imbalances are known to result in pain and dysfunction in the low back and other areas, reduced performance in sports and exercise activities, including running, and sports injuries, including runner’s knee.

Muscles tend to work in pairs of agonists and antagonists. When a muscle or group of muscles shortens and moves a joint, it acts as an agonist. The muscle or group of muscles on the opposite side of the joint that stretches to allow this joint movement acts as an antagonist. When the joint is moved in the opposite direction, the roles switch: The agonist becomes the antagonist and vice versa.

The agonists and antagonists that act on each joint should have a good balance of strength. If the muscles that move a joint in one direction become significantly stronger or weaker than those that move it in the opposite direction, a muscle imbalance exists and the potential for joint breakdowns is greater. It’s like a bicycle wheel that becomes “out of true,” hence dysfunctional, because the spokes on one side are tighter than those on the other side.

Muscle imbalances develop when a person uses a certain muscle group much more than the opposing muscle group. During sitting, certain muscles tend to be active, while other muscles that oppose these active ones remain inactive. As a result, particular muscle imbalances are frequently seen in men and women who spend a lot of time sitting. The most prevalent ones are weak deep abdominal muscles, tight hip flexors, weak buttocks and hips, tight hamstrings, and weak quadriceps.

The deep abdominal muscles wrap like a corset around the midsection of your body. Their job is to maintain upright trunk posture and stabilize the pelvis and lumbar spine during activities. When you sit in a chair or seat, however, you don’t naturally use your deep abdominal muscles unless you make a conscious effort. Consequently, these muscles tend to become weak in those who spend a lot of time sitting. It’s the hip flexors, which are muscles that cross the hip joint in front of the body, that do the job of keeping the trunk upright when we sit in chairs and seats. As a result of using our hip flexors for multiple hours every day, these muscles become really tight. (Interestingly, the deep abdominals are much more active, and the hip flexors less active, when we sit cross-legged on the floor, as our ancestors probably did commonly before the La-Z-Boy was invented.)

There is a common misconception that a tight muscle is structurally shortened. In fact, a tight muscle is simply one that holds tension due to a constant low-level activation by the brain. In the case of tight hip flexors, the brain spends so much time activating these muscles during sitting that it loses the ability to fully relax them.

Tight hip flexors create problems for body alignment by causing a forward tilt of the pelvis. When you’re standing, the hip joints should be in a neutral position relative to the pelvis. But due to tight hip flexors, the vast majority of us stand with the hip joints slightly flexed. When you stand with your hip joints slightly flexed, your center of mass is in front of your balance point, so the body compensates by tilting the pelvis forward and arching the lower back. This postural compensation puts a tremendous strain on the hamstrings, which become active in pulling down on the rear side of the pelvis to correct for its forward tilt. As a result of constantly holding tension when you stand, the hamstrings become relatively strong compared to their antagonists, the quadriceps.

The muscles of the buttocks and outer hips are required to relax and stretch as you sit. As a result of spending so much time relaxed and stretched, these muscles, like the deep abdominals, become weakened.

All of these imbalances have consequences for your running performance and injury risk. Running involves heavy use of the hip flexors and hamstrings, so it tends to strengthen these muscles, thus exacerbating their tightening and the strength imbalance between the hamstrings and quadriceps that sitting causes. Runners with tight hip flexors are unable to fully extend their hips in the push-off phase of the stride. You should be able to achieve a 10-degree backward extension of the hip during push-off. If, like most runners, you cannot, then you can’t completely use your strong extensor muscles—your gluteus maximus and your hamstrings—to generate thrust. In addition, tendonitis of the hip flexors often develops in runners with tightness in these muscles.

Weak quadriceps muscles are commonly implicated in causing patellofemoral pain syndrome, or runner’s knee—the injury I know all too well from personal experience (and the most common running injury of all). One of the four quadriceps muscles, called the vastus medialis oblique (VMO), is responsible for pulling the kneecap into alignment with the femur as the leg extends. Weakness in this muscle often results in improper tracking of the kneecap during running, meaning the kneecap fails to come fully centered as the leg extends and the foot makes ground contract, causing chafing between the kneecap and femur, like an askew door that gouges its frame every time the door is shut.

Weak buttock and outer hip muscles compromise the stability of the hips, pelvis, and even the knees. An excessive internal rotation of the thigh is often seen in runners with weakness in these areas, a compensatory movement that is known to cause iliotibial band syndrome, hip and pelvic injuries, and runner’s knee.

Runners with weak deep abdominal muscles frequently exhibit an excessive forward tilt of the pelvis when running. This error may contribute to various injuries, including low back pain and hip flexor tendonitis.

ANTI - SITTING

Fortunately, what is tightened can be loosened, and what is weakened can be strengthened. There might not be much you can do about the amount of time you spend sitting each day. But by learning to sit differently, and by practicing a few simple stretches and strengthening exercises, you can reverse the imbalances that sitting causes and avoid their painful consequences.

The first thing you can do is to improve your sitting form by activating your deep abdominal muscles. As you’re sitting, think about drawing your navel toward your spine. Make sure you continue breathing normally. You’ll feel more stable in your sitting and you’ll sit taller. When you stand up, do the same thing. For example, when you’re waiting in line at the grocery store or at the bank, pull your navel toward your spine and pull your pelvis upward. It’s a small enough movement that no one will notice what you’re doing, but if you conscientiously counteract your automatic postural tendencies in this way whenever you think of it, you will greatly improve your posture and core stability over time.

You can get the job done a lot faster with corrective stretches and strengthening exercises, however. The following stretches and strengthening exercises will correct the underlying muscle imbalances that are caused by excessive sitting more quickly because they really challenge your tight muscles to stretch and your weak ones to work against resistance. (Not included are strengthening exercises for the deep abdominals, which are the focus of the core workouts presented in chapter 5.) Do the stretches once a day and the strengthening exercises two or three times per week. You can do them anytime; I like to perform both the stretches and strengthening exercises while watching ESPN in the evening; another option is to do the stretches immediately after your runs and the strength exercises in the context of your strength workouts.

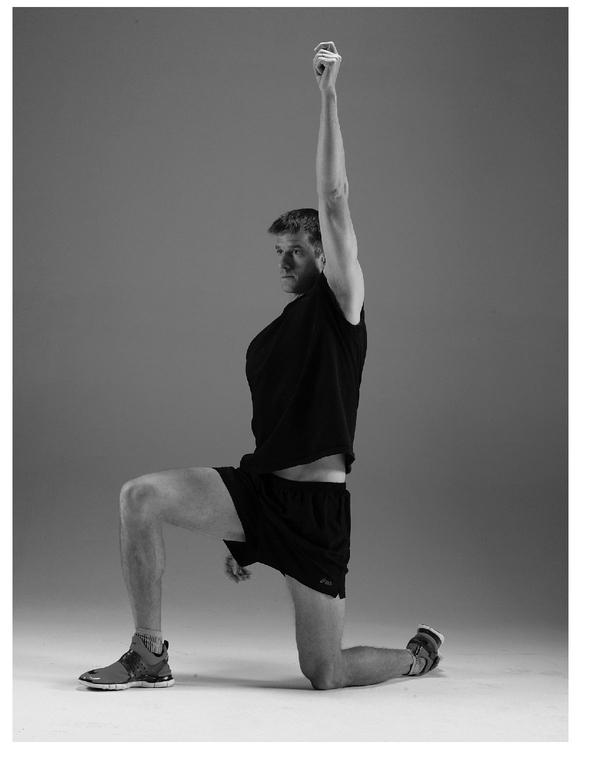

Lunge Stretch

Loosens tight hip flexors

Kneel on your left knee and place your right foot on the floor well in front of your body. Draw your navel toward your spine and roll your pelvis backward. Now put your weight forward into the lunge until you feel a good stretch in your left hip flexors (located where your thigh joins your pelvis). You can enhance the stretch by raising your left arm over your head and actively reaching toward the ceiling. Hold the stretch for twenty seconds and then repeat on the right side.

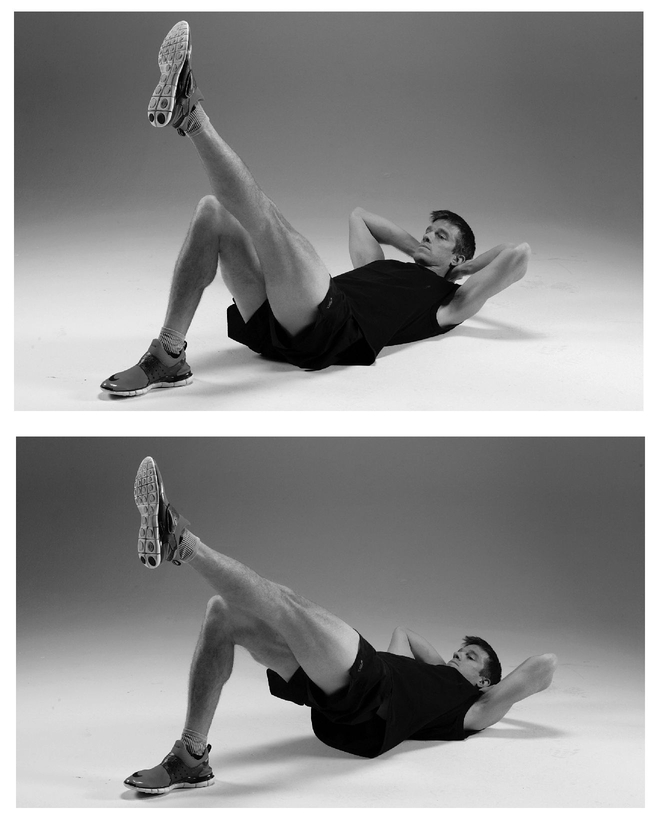

Supine Hip Extension

Strengthens weak buttocks

Lie faceup on the floor with your knees bent, both feet flat on the floor, and your arms folded on your chest. Straighten your left leg fully so that your left thigh remains in line with your right thigh. Press your right foot into the floor and contract your buttocks, causing your hips to lift until your torso comes in line with your thighs. Pause for one second and relax, keeping your left leg extended. Complete ten to twelve repetitions and then switch legs.

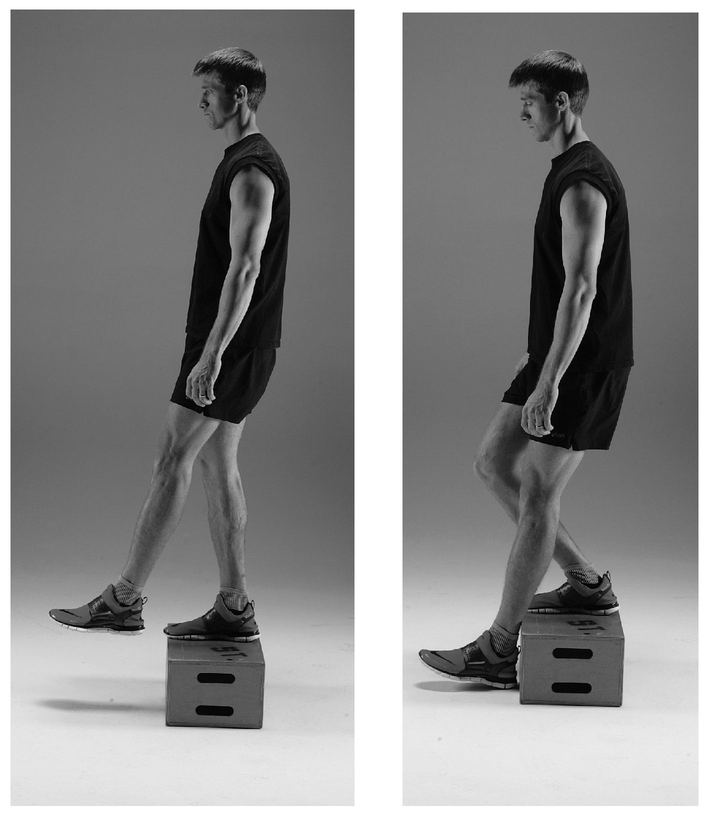

VMO Dip

Strengthens weak quadriceps

Stand on an exercise step that’s eight to twelve inches high. Pick up your left foot and slowly reach it toward the floor in front of the step by bending your right knee. Allow your left heel to touch the floor but don’t put any weight on it. Return to the start position. Complete eight to twelve repetitions and then switch legs.

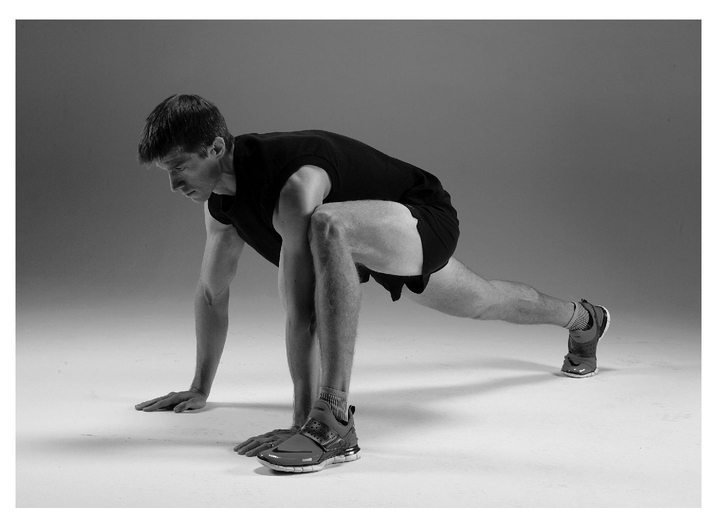

Spider Stretch

Assume a standard push-up position. Pick up your left foot, sharply bend your left knee and flex your left hip, and reposition the foot next to your left hand on the pinky side. Allow gravity to sink the weight of your body toward the floor slightly until you feel a warm stretch in your left hamstrings. Hold the stretch for 20 seconds. Now reverse your position and stretch the right hamstrings.

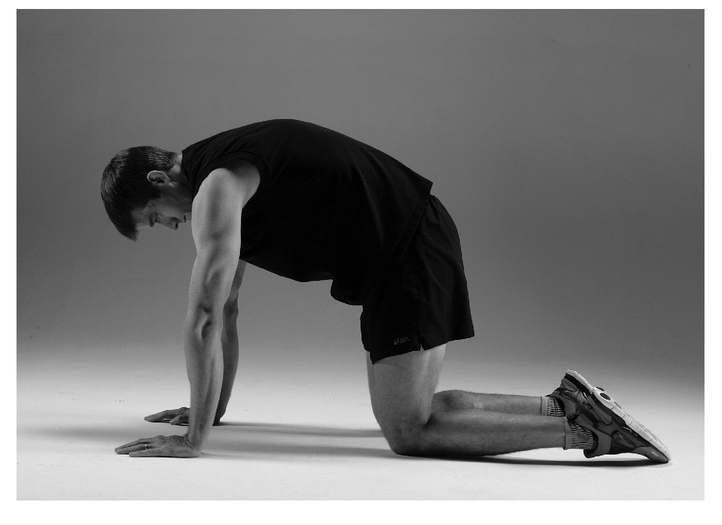

Cat Stretch

Loosens tight lower back muscles

Kneel on your hands and knees. Begin with your spine in a neutral position. Now round your back like a scared cat, pushing your mid-spine as high toward the ceiling as you can. Hold the stretch for five seconds and relax. Repeat the stretch five times.

HOW SHOES CAUSE INJURIES

Until relatively recently in history, humans ran exclusively barefoot. There is a major difference between the way humans run with shoes and the way we run barefoot. Specifically, people tend to overstride when wearing shoes, but not when barefoot. Exactly zero percent of runners overstride, landing heel-first with the foot ahead of the body, when running barefoot. The reason is simple: If you land heel-first while running barefoot you will experience significant pain in your heel and quickly bruise it. But with shoes on, 80 percent of runners overstride and land heel-first.

Why does the switch from barefoot to shod running cause so many of us to change the way we run? I suspect that running shoes confuse the brain in a way that causes it to select the wrong motor pattern—namely, a motor pattern that is meant for walking, which involves a heel-first footstrike whether the foot is shod or unshod.

The heel of the foot contains proprioceptive nerves that transmit information about the hardness of the running surface and the force of impact to the brain. This information probably helps the brain decide whether to adopt a running gait or a walking gait. A slower pace results in a less forceful impact and a greater likelihood that the brain will determine a walking gait is most appropriate. But cushioned running shoes produce a softer impact at any speed. Again, the foot always lands heel-first during walking. So when we run with cushioned running shoes, the actual pace demands a running action, in which both feet lose contact with the ground at certain moments, but the softness of impact encourages a heel-first landing, as in walking. Consequently, 80 percent of us adopt a hybrid, overstriding walk-run action that increases injury risk by increasing ground contact time, reducing joint stability, and causing a more abrupt and extreme concentration of impact forces in the joints and other susceptible tissues.

This explanation is somewhat speculative. But what is certain is that shoes make most of us run unnaturally, specifically by overstriding, and this is a major cause of overuse injuries. The rigidity of shoes also prevents the foot from deforming upon ground contact in the natural wavelike pattern that the unshod foot normally uses to absorb impact. As a result, impact forces are sent shooting up the leg, concentrating in the knee, hip, pelvis, or even the lower spine.

I learned about these injury-causing effects of running shoes while researching a chapter on shoes for my book The Cutting-Edge Runner. From that point forward I often wished that one of the major shoe manufacturers would develop a “barefoot running shoe” that encouraged the wearer to run more naturally. Then Nike came out with a running shoe called the Free 5.0, a revolutionary piece of technical footwear for runners that fulfilled my wish exactly. Nike promoted the Free 5.0 as a foot-strengthening tool designed to be worn only once a week. But I was not fooled. Nike couldn’t very well admit that the Free 5.0 was really designed to allow the wearer to run naturally, thus reducing injury risk, because in doing so they would have to admit what their other shoes were doing: causing injuries! Fair enough.

The Nike Free 5.0 had minimal cushioning—no more than was needed to run pain-free on asphalt, which is probably less than you think you need. It was extremely flexible, and provided no lateral stability. In other words, it had none of the features that runners have been taught to think of as virtues in a running shoe, but really aren’t, because it’s these very features that make wearing a running shoe unlike running barefoot. For example, the only reason conventional running shoes require stability features such as a heel counter is to overcome the instability that running shoes cause in the first place by elevating your feet above the ground on a narrow, mushy platform. If you get rid of the excessive cushioning, your running shoe has no more need for stability features than barefoot antelope hunters on the African savanna of twenty thousand years ago needed stability features added to their feet.

I bought a pair of Free 5.0s the day they became available to the public and immediately started wearing them for every run except track workouts (in which I continued to wear super-lightweight racing flats). Sure enough, I discovered that when my feet landed on the ground they were able to pronate and deform as they were evolutionarily designed to do, and as a result my feet and ankles absorbed much more impact force than they ever did in conventional running shoes, and consequently transferred less impact force to my long-suffering knees and hips. Despite Nike’s dire warnings not to run more than 20 minutes in the Free 5.0s, I ran as much as 60 miles a week in them, and I even ran my comeback marathon in them, and far from creating any problems of their own, these shoes clearly helped prevent injuries that my previous shoes were contributing to.

Interestingly, when Nike came out with the Free 4.0—an even more minimalist running shoe —the company dropped the whole foot-strengthening shtick and provided guidelines for gradually making the Free 4.0 one’s full-time running shoe. The latest version of the Free, the 3.0, is lighter and more flexible still. I now split time between this shoe and something called the Vibram Five Fingers (

www.vibramfivefingers.com), which is not a shoe but a sort of foot glove that makes the Nike Free 3.0 seem bulky by comparison. I rave to other runners about the Five Fingers all the time, but most are afraid to run in something that allows them to literally feel the texture of the twigs, leaves, and pebbles they step on. There are, however, less-extreme options available to runners who are willing to move in the barefoot direction, but prefer to do so cautiously. Specific models include the Puma H Street (not technically a running shoe) and the Adidas ZX Racer.

While I am fully convinced that minimalist running shoes are less likely to cause injuries than conventional running shoes, this proposition has not been subjected to formal scientific evaluation. Therefore, rather than give you an unqualified recommendation to make the same transition I have made, I will leave you with the following footwear suggestions:

• If you are currently uninjured, do not have a significant injury history, and like your current running shoes, keep using them.

• If you are currently injured, have a significant injury history, or do not like your current running shoes for any reason, consider buying a pair of minimalist running shoes and wearing them once a week for a short run.

• If you find the minimalist shoes comfortable and they don’t cause any problems, consider increasing the number of runs you wear them for, one by one. Don’t feel compelled to wear them for every run or even for more than one run per week. Any amount of time you spend in them will likely reduce your injury risk.

• If you do not like the feel of the minimalist shoes or if wearing them does not seem to reduce your injury risk, you may need to consider going in the opposite direction: switching to a shoe with more cushioning and/or more stability, and possibly having a sports podiatrist fit you for prescription orthotics.

As a general rule, the running shoe you find most comfortable will be the one you’re least likely to get injured in. The feeling of comfort in a particular running shoe represents your proprioceptive system’s way of telling your brain that the shoe is allowing your muscles and connective tissues to move in more or less the way they prefer to move.

RETRAINING YOUR GAIT

Merely correcting your muscle imbalances and switching your footwear will not automatically make you run more naturally. These measures will make you better able to run more naturally, but in order to actually run more naturally you must consciously modify your stride. Because you repeat the stride action so often as a runner, the motor patterns that govern your stride are deeply ingrained within the motor centers of your brain. Correcting your muscle imbalances and changing your shoes will alter these patterns slightly by providing altered proprioceptive feedback to your brain, but the only way to make significant improvements to your stride, such as correcting overstriding and internal thigh rotation, is to proactively retrain your gait. Use the guidelines provided in chapter 5 to correct your unnatural stride patterns with proprioceptive cues and technique drills.

WHEN PAIN STRIKES

Pain is unpleasant by definition, and it is usually thought of as a negative thing. But the ability to feel pain is really a gift and an asset. Pain is almost always caused by damage to body tissues. The fact that we feel pain enables us to react in ways that help us prevent further damage.

There is a difference between feeling pain and reacting to pain. It is possible to reflexively react to pain signals without consciously feeling pain, and to feel pain without reacting to it. Simple organisms such as worms have pain receptors that enable them to shrink away from painful stimuli, such as being poked with a needle, but they do not have the mental apparatus to experience pain in a way that is even remotely similar to the way we do. The advantage that conscious awareness of pain confers is that it enables us to respond to pain in far more sophisticated ways—including ignoring pain in some instances!

The human body is filled with millions of specialized pain receptor nerves. When these nerves are activated by pressure or another such stimulus, they send an electrical signal to the brain. (Interestingly, the brain itself does not contain pain receptors, and for this reason brain surgery can be performed without anesthesia.) You might assume that these signals travel to a specific brain region that is responsible for producing the conscious feeling of pain. In fact, no such brain region exists. The conscious experience of pain appears to be produced as a result of activity in multiple brain regions.

TABLE 9.1 Common Running Injuries

The following table provides information to help you identify and overcome six of the most common running injuries.

Much like fatigue, pain seems to represent a brain “decision” to respond to a pain stimulus. The feeling of pain lets you know that the brain has already executed some kind of reaction to it (such as pulling your hand away from a flame) and also discourages efforts to consciously override this reaction.

The fact is, however, that you can override pain in two ways. First, your brain can simply fail to produce a conscious feeling of pain when this feeling might do more harm than good. This is what happens in a state of shock, in which pain is delayed for several minutes or more following a grievous injury. In cases of shock, temporary numbness enables the injury sufferer to take lifesaving actions that might be impossible if a degree of pain commensurate to the injury were experienced. It is also possible to feel pain yet override the natural stimulus response to that pain in situations where the natural response might only make matters worse. The classic example is the pain felt when picking up a full pot of boiling soup by its hot iron handle. In this case, the natural stimulus response of dropping the soup pot might only make matters worse.

Competitive runners often override the pain message of injuries, as I did when my forty-month knee injury began. Competitive runners place high value on achieving race goals, are hyperaware of the fact that consistent training is required to achieve these goals, and have a high tolerance for pain, thanks to their familiarity with the discomfort of extreme exercise fatigue. These factors make the decision to ignore injury pain understandable and all too feasible, but they do not make it wise. Take it from one who learned the lesson in almost the hardest way possible: You will come out ahead in the long run (so to speak) if you adopt a zero tolerance policy toward injury pain (or localized musculoskeletal pain, which is totally distinct from fatigue-related pain), and react to it with a hair trigger by ceasing your running as soon as the pain reaches red-flag level and not running again until you can do so without pain.

Some injuries are caused by too-sudden changes in training. For example, bone strains (better known as shin splints) typically occur when running mileage is increased too quickly. Achilles tendinosis often coincides with the abrupt introduction of high-speed running. Injuries caused by doing too much too soon can be overcome easily with a reduction in training followed by a more gradual ramp-up. Let pain be your guide.

When muscle imbalances, shoes, and/or stride flaws are the major causes of an injury, simply backing off your training and easing back into it after your pain symptoms have subsided may not be adequate to overcome the injury. Traditional treatments such as icing and anti-inflammatory medications will also do you little good in this regard. Until and unless you fix the underlying cause(s) of the injury, it will probably return each time you attempt to ramp up your running workload beyond a certain level. Your first step is to identify the injury. Once you’ve identified the injury, a sports medicine specialist and/or sports physical therapist can help you identify muscle imbalances, stride errors, and footwear-related issues that may have caused the injury. Table 9.1 provides some very basic guidelines to identify and correct six common running injuries.

In the meantime, stay fit by replacing your running workouts with similar workouts in a nonimpact aerobic activity such as bicycling or deep water running that you can do pain-free. Doing so will not only keep you fit while your injury heals and you correct its causes, but it will also greatly reduce the temptation to resume running too quickly.