Vexed again; perplexed again;

Thank God, I can be oversexed again.

Bewitched, bothered, and bewildered am I.

—Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers,

“Bewitched”

It is not uncommon for a studio to buy the screen rights to a Broadway play before it opens to get the jump on rival studios. Samuel Taylor’s play Sabrina Fair: A Woman of the World had been submitted to Paramount in typescript months before the New York premiere in November 1953. A reader in the story department turned in an enthusiastic report on the play, and this prompted Wilder to get Paramount to purchase the film rights immediately.

Wilder’s decision turned out to be a wise one; Taylor’s four-act play was a hit and eventually racked up 318 performances. Sabrina is the daughter of Thomas Fairchild, the chauffeur on the estate of the wealthy Larrabee family on Long Island. Sabrina nurtures a crush on David Larrabee, an irresponsible playboy, but eventually falls for Linus, David’s older, more sensible brother. Neither David nor Linus takes much notice of Sabrina, however, until she returns from a sojourn in Paris, where she has been transformed into “a woman of the world.”

Samuel Taylor was invited to Hollywood to collaborate with Wilder on the screenplay in the summer of 1953. He had absolutely no experience in writing for the screen and found Wilder an exacting taskmaster. For a start, Wilder wanted the film to be called Sabrina, not Sabrina Fair. Taylor pointed out that he drew the play’s title from John Milton’s masque Comus (1637). Sabrina is the ancient name of the goddess of the River Severine: “Sabrina Fair . . ./ Listen for dear honor’s sake, / Goddess of the silver lake.”1 Wilder insisted that Sabrina Fair sounded like one of those dreary English rural comedies, set at a country fair, that inevitably died at the box office in America. Wilder, as usual, got his way, and the title of the film was shortened to Sabrina.

Obviously, Wilder did not regard Taylor’s play as a sacred text, any more than he thought Bevan and Trzcinski’s Stalag 17 was scripture. Taylor was dismayed when Wilder began excising large chunks of the play’s text. Wilder explained that a four-act comedy was too long for a movie under any circumstances, since most stage comedies were three acts at most. What’s more, Wilder had to make cuts to make room for additional scenes in the screenplay; for example, he wished to dramatize on screen Sabrina’s stint in Paris. This episode is only referred to in the play, which is set entirely in the Larrabee mansion. Wilder also aimed to make the screenplay sharper and funnier than Taylor’s talky play, in which the dialogue overexplained everything. In this, Wilder succeeded.

Wilder and Taylor finished a preliminary rough draft by July 1953. By then Taylor had found working with Wilder too taxing. The frustrated playwright abruptly threw up his hands one day and announced that he was returning to New York to oversee the rehearsals of his play, scheduled to open on November 11, 1953. In the Broadway theater, Taylor reasoned, the playwright was respected and listened to, whereas in Hollywood the playwright had little control over how his work was recast for the screen. In 1974 I met Taylor in New York; by then he had received plaudits for his screenplay for Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Taylor confirmed that he had found Wilder difficult to work with. Nevertheless, he respected Wilder, like Hitchcock, “as a genuine auteur, the true author of every film he makes.”

Wilder heard from William Holden about Ernest Lehman, who had just completed the screenplay for Robert Wise’s Executive Suite (1954) at MGM. Holden was starring in the movie, which was still in production; he informed Wilder that, although Executive Suite was Lehman’s first movie script, he clearly had an ear for good screen dialogue. In checking on Lehman with a fellow screenwriter at MGM, Wilder learned that Lehman had graduated from City College in New York and had since been freelancing as a writer. The other writer recommended Lehman to Wilder, saying that, on the grounds of Lehman’s script for Executive Suite, it was evident that he had a gift for the tongue-in-cheek, wry repartee that had distinguished the best films of Ernst Lubitsch. That was all that Wilder had to hear to prompt him to phone Lehman and ask him to replace Taylor immediately.

Lehman told me when I met him at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976 that he inquired when Wilder wanted him to show up at Paramount, and Wilder replied, “How about this afternoon?” Wilder then explained to Lehman the sad state of affairs. Paramount had established a starting date for principal photography in the last week of September 1953, with shooting running through most of November. It was already August, and Wilder had completed only a preliminary rough draft of the script. So he had to get rolling on the final shooting script posthaste. Lehman moved over to Paramount from MGM that afternoon.

There is an old adage in Hollywood that it is suicidal to begin principal photography on a film before the final shooting script is completed. Wilder was violating that sage bromide in spades. The film was already in preproduction, and Wilder and Lehman would have to continue hammering out the final shooting script all the way through the production period. “This was a picture that was still being written and shaped as we went,” Wilder moaned. “I don’t write; I rewrite.”2

Lehman was no pushover when it came to defending his point of view; in this respect Wilder had met his match. Lehman could be “as stubborn as the director; and their collaboration was stormy when it wasn’t openly hostile,” writes Donald Spoto.3 Like Edwin Blum, Ernest Lehman never got used to the fact that Wilder dished out insulting wisecracks even to people he liked. Lehman told me that Wilder called him all sorts of nasty names, ranging from “a eunuch, a misogynist, and a queer” to “a middle-class Jewish prude.” Lehman concluded, “Wilder never grasped how his jibes offended his friends.” Not surprisingly, Lehman found collaborating with Wilder exasperating and exhausting. When Lehman tossed Wilder a line of dialogue, Wilder invariably replied, “Very good; but let’s make it better.”4 What Lehman did not know was that Wilder was telling Lehman what Lubitsch had said repeatedly to him.

Despite Wilder’s quarrels with Lehman, which recalled his arguments with Brackett, they turned out what Philip Kemp terms “a witty, literate, well-paced, and stylish” screenplay for Sabrina. Yet Richard Corliss has written off Lehman as a “mere service station attendant of other writers’ vehicles.” Kemp counters that Corliss’s view seems “singularly inapt,” in view of Lehman’s shrewdly gauged collaboration with Wilder on Sabrina.5

Since preproduction was in full swing when Lehman began working on Sabrina, Wilder was busy with casting the picture as well as writing the final shooting script. He settled on Audrey Hepburn to play the title role; as a matter of fact, Wilder considered the movie first and foremost a vehicle for her. Hepburn’s first big film was Roman Holiday, in which she played a runaway princess in Rome; it would not be released until September. But its director, William Wyler, assured Wilder that Hepburn had given a star-making performance. “I saw the test that Wyler made with her,” Wilder remembered, “and I was absolutely crazy about her.”6 In the test she radiates poise and beauty as she recalls studying ballet when she was growing up.

When Hepburn’s casting was announced, Wilder gave a press conference in which he decried “the number of drive-in waitresses” being groomed for stardom; they just “wiggle their behinds at the camera.” By contrast, said Wilder, Audrey Hepburn, at age twenty-four, was known for her grace and elegance. “God kissed her on the cheek, and there she was.” Hepburn had class and intelligence as well as beauty, he concluded. “She looks as if she could spell schizophrenia.”7 Later on he told Hepburn that, for him, it was love at first sight when she walked onto the set. He confessed that he talked in his sleep about Audrey, but fortunately his wife’s name was Audrey as well, “so I got away with it.”8 In Sabrina Audrey Hepburn grows up to be a fairy princess solely because of her “charm and beauty,” Peter Bogdanovich writes. Wilder retained the play’s Cinderella theme in his film; as he put it, there could be no more perfect Cinderella than Audrey Hepburn.9

Wilder had no trouble in convincing William Holden to do his third Wilder film, as David Larrabee. Casting Linus Larrabee, however, presented a knotty problem. Cary Grant had agreed to play the part of David’s older brother, but he changed his mind and bowed out one week before filming was to begin. Grant had decided he did not want to play a stuffed shirt like Linus who was in love with a much younger woman. Wilder needed a star of Grant’s stature, and Humphrey Bogart was available, so Wilder offered the part to Bogart. At fifty-four, Bogart was twenty-five years older than his wife, Lauren Bacall, and yet he had made four pictures with Bacall. So Bogart as Linus could be a credible love interest for Audrey Hepburn’s Sabrina.

Wilder went to Bogart’s home in Holmby Hills to convince him to take the part. Bogart accepted the role reluctantly; he had an inferiority complex about playing a part originally intended for Cary Grant. Still, Bogart was mollified in some degree by the substantial salary of $200,000 he would receive—considerably more than Holden ($80,000) and Hepburn ($25,000) were allotted. Bogart cited an old bromide attributed to Sam Goldwyn, “You must take the bitter with the sour.”10 Still, throughout the shoot, Bogart needled Wilder about preferring Grant to him. As a matter of fact, one of the handicaps Wilder and Lehman experienced in composing the final shooting script was that they had to tailor the role of Linus for Bogart, who, unlike Grant, had never played light romantic comedy.

This is not to say that Bogart was miscast as Linus Larrabee. Despite his tough-guy image in pictures, Bogart’s background was one of “inherited wealth,” as Richard Schickel is at pains to emphasize in Bogie. He grew up in a privileged, upper-class family in New York City. What’s more, he had often played classy romantic leads on the Broadway stage in the 1920s. He was probably the first stage actor to utter to his country club companions a line that has since become a cliché: “Tennis, anyone?”11

Wilder managed to corral for Sabrina three trusted associates who had collaborated with him on previous pictures: film editor Arthur Schmidt (Sunset Boulevard), composer Frederick Hollander (A Foreign Affair), and cinematographer Charles Lang (Ace in the Hole). Since Sabrina was scheduled to go before the cameras with two weeks of location work on Long Island, Wilder, Lehman, Lang, and Doane Harrison, Wilder’s longtime supervising editor, embarked for New York on September 22, 1953. The rest of the film unit would follow in a couple of days.

Wilder had no trouble securing an ideal location at Glen Cove, Long Island, to stand in for the Larrabee estate in the movie; it was the property of Barney Balaban, the president of Paramount. After shooting exteriors at Glen Cove, the cast and crew returned to Hollywood, where Wilder was scheduled to film interiors at Paramount for seven weeks. Filming resumed on October 6. The following day, Wilder submitted the shooting script to the front office. “But the shooting script was still not finished,” said Wilder.12

By day, Wilder directed the picture while Lehman labored on the script alone. In the evenings, they worked together, with Wilder kibitzing on what Lehman had written. The writing partners continued grinding out new pages in a frenzy. But they could scarcely keep up with the shooting schedule; they wrote some scenes the night before they were to be shot. Lehman’s nerves got increasingly ragged, while Wilder survived each night on black coffee and cigarettes. “It was agonizing, desperate work,” Lehman remembered, “and at times our health broke down from the effort.” Wilder had some sleepless nights when his back troubled him, as it always did when he was operating under a great deal of stress.

One afternoon, Wilder ambled up to Harrison, his right-hand man, and said casually, “Please get the electricians to invent some complicated lighting effects for the next scene that will take some time.” Puzzled, Harrison inquired, “What for?” Without raising his voice, Wilder replied, “We haven’t got the goddamed dialogue written yet!” Harrison then instructed Lang to have the crew create a varied range of gray and dark, shadowy tones for the night scene coming up, so that Wilder and Lehman could finish revising the scene. Little wonder that Lehman called Sabrina the scariest experience he ever had in his life.13

The shoot also proved to be an ordeal for most of the cast and crew, said Martha Hyer. She played David Larrabee’s fiancée, whom David largely ignores once he becomes attracted to Sabrina. “There was much friction, side-taking, and intrigues during the filming,” she said, especially from Bogart. Perhaps he was insecure because “he didn’t feel comfortable in the part.”14 Bogart’s son Stephen put it more bluntly. “Bogie seemed to bask in his role as a troublemaker,” and make trouble he did on the set of Sabrina.15 According to his biographer, Jeffrey Meyers, Bogart “was unstable, edgy, and somewhat paranoid” about playing high comedy. Furthermore, he was “drinking more than was good for him.”16 Bogart had always been a heavy drinker. He no longer drank his lunch, but he regularly had his secretary, Verita Petersen, bring him a glass of Scotch on the set at five o’clock, an hour before quitting time. As he sipped the whiskey between takes, Bogart became even more dyspeptic and surly.

As filming progressed, Wilder took to inviting Holden and Hepburn to his office for drinks at the end of the day. Bogart, whom Wilder did not find congenial company, was not included. When Wilder discovered that Bogart felt ostracized, however, he gave Bogart a belated invitation to join the group each afternoon. Bogart curtly turned Wilder down, since he had not been asked to join Wilder’s “clique” at the outset. From then on, the battle lines were definitely drawn. Bogart resented Wilder, Holden, and Hepburn as having formed a conspiracy against him.

Wilder shrugged off Bogart’s antipathy as best he could. “I get along very well with actors,” he declared, “except when I have to work with sons-of-bitches like Mr. Bogart. . . . He was crazy, Bogart was; I knew I was on his list of bastards.” But Wilder consoled himself that, once a picture is finished, a director’s relationship with an actor is over. After all, “you’re not married to them!”17

Bogart continued to snipe at Wilder and at his two costars. At one point Wilder handed Bogart the new script pages. After looking them over, Bogart inquired whether Wilder had any children. “Yes,” Wilder responded, “a thirteen-year-old daughter.” Bogart pitched the pages back at Wilder and barked, “Did she write this?”18

Bogart even maliciously mocked Wilder’s German accent. When Wilder was under pressure, his accent became more pronounced. One day he gave a direction to Bogart, “Giff me here a little more faster.” Bogart jeered at him: “Hey, Wilhelm, would you not mind translating that remark into English? I don’t schpeak so good the Cherman, jawhohl!”19 Bogart later explained to the press that he thought Wilder was too authoritarian. Wilder, he said, was “the kind of Prussian German with a riding crop.” Bogart continued, “He’s the type of director I don’t like to work with. He works with the writer and excludes the actor. It irritated me, so I went to work on him. One thing led to another. This picture Sabrina is a crock of crap anyway.”20

On another occasion, Bogart complained that Wilder strutted around the set like a “kraut bastard Nazi son-of-a bitch.”21 Wilder finally had had enough. After all, it was common knowledge in the film colony that Wilder’s mother, stepfather, and grandmother were victims of the Holocaust. Wilder addressed Bogart in measured tones: “Mr. Bogart, some actors are talented and some actors are shits. You, Mr. Bogart, are a talented shit.”22

Wilder told journalist Ezra Goodman a couple of years later that Bogart “surrounds himself with whipping boys, aspiring young directors like Richard Brooks,” who had directed Bogart in the Korean War movie Battle Circus (1953). “He exposes them to ridicule; and they have to like it,” because they want to direct an established star like Bogart. But experienced directors like Joseph Mankiewicz, who directed Bogart in The Barefoot Contessa (1954), and, of course, Billy Wilder, “don’t take that from him.”23

Bogart’s paranoia particularly focused on William Holden, who was the matinee idol Bogart had once been. Bogart accused Holden of trying to steal the picture by upstaging him during their scenes together. Moreover, Bogart noticed Holden puffing on a cigarette and was certain that Holden was attempting to make him cough when saying his lines. Bogart stormed at Wilder, “That fucking Holden over there, waving cigarettes around, blowing smoke in my face, crumpling up papers. I want this sabotage ended, Mr. Wilder.”24 Wilder, who wrote “Cum Deo” on the first page of every screenplay, began to think God was deserting him. He rolled his eyes to the heavens and did not reply to Bogart. In his effort to needle Holden, Bogart called him “lover boy,” ridiculing Holden’s good looks. Bogart implied that “pretty boy” Holden was merely a movie star and not a serious actor.

“I hated the bastard,” said Holden; “he was always stirring things up when he didn’t have to.”25 Still, Holden usually lived up to Wilder’s expectations as an agreeable and cooperative actor, except for those times when he was in his cups. Holden’s drinking problem had become more pronounced since Sunset Boulevard and Stalag 17. Bogart too was a heavy drinker, but he was more in control of his drinking than Holden. One afternoon, after he had had a liquid lunch, Holden showed up on the set bleary-eyed, in an alcoholic stupor. He was in no condition to work, and he kept forgetting his lines. “Methinks the lad has partaken too much of the grape,” Bogart sneered, adding that Holden was “a dumb prick.”26 Holden, enraged, threw a punch at his costar, and Bogart retaliated. Wilder, acting as referee, had to pull them apart; he then ordered Holden to retire to his dressing room and rest until he sobered up. Asked by a reporter for his opinion of Bogart, Holden answered with circumspection that Bogart was “an actor of consummate skill, with an ego to match.” Yet the antipathy between Bogart and Holden was never visible in their performances on the screen, and as Wilder was fond of saying, “What the audience sees is all that matters.”27

Not even the winsome Audrey Hepburn could escape Bogart’s wrath, since he saw her as part of the clique with Wilder and Holden. Wilder and Lehman were still falling behind in their revisions of the shooting script, and one morning when Hepburn arrived at the studio, she was handed new pages of revised dialogue. The pages had been ripped out of Lehman’s typewriter only a few hours before. When Hepburn fumbled her lines during the first take, Wilder was understanding, but Bogart, who had an uncanny facility to master his lines, smirked, “Maybe you should stay home and study your lines, instead of going out every night.” Hepburn smiled graciously; she was a young, inexperienced actress and Bogart was an old pro. She was not going to bicker with a cranky star. Bogart later said to a reporter, speaking of Hepburn, “Yeah, she’s great, if you can give her twenty takes.”28

Audrey Hepburn was not going out every night, as Bogart charged, but she did spend some nights with William Holden, with whom she was having an affair. They would meet in a small apartment that Holden had rented for their secret trysts. When the picture wrapped, Holden offered to divorce Ardis and marry Audrey. “When Audrey learned that Holden was no longer able to have children, her affection cooled,” writes David Hofstede. She wanted to be a mother as well as a wife; she ended the affair immediately.29 Wilder claimed that he was not aware of their love affair while he was shooting the picture; Holden and Hepburn made every effort to conceal it from him.30

Bogart’s “list of bastards” also included Ernest Lehman, since Bogart resented that Wilder spent more time conferring with his writing partner than with the actors. One day Lehman rushed onto the set to distribute the new script pages that he and Wilder had finished rewriting only that morning. He did not bring enough copies, however, and he ran out before he got to Bogart. “Where’s mine?” Bogart demanded. “I don’t have another copy,” Lehman mumbled sheepishly. Bogart hollered, “Get that City College bum out of here and send him back to Monogram [a Poverty Row studio] where he belongs!”31

Lehman, still a young screenwriter, was devastated by Bogart’s vicious outburst. Wilder called a halt to the rehearsal: “There will be no further shooting on this picture until Mr. Bogart apologizes to Mr. Lehman.” Bogart walked over to Lehman and said, “Come on into my dressing room for a drink later, kid.” The rehearsal resumed.32 Like Holden, Wilder acknowledged that Bogart was “a tremendously competent actor.” Nevertheless, Bogart was also a boor; “his barbs were uncouth.” Wilder continued, “I learned from the master, Erich von Stroheim”; compared to him, Bogart’s needling “was just child’s play. You have to be much wittier than Bogart to be that mean.”33

Not surprisingly, the pressure of reworking the screenplay under the gun was getting to be too much for Lehman. During one story conference, he collapsed from nervous exhaustion and began sobbing uncontrollably. Wilder put his arm around him and whispered, “Nobody’s ever worked harder than you, Ernie.” He told Lehman to grab a cab, go home, and rest; he then closed down production for a couple of days. Lehman’s physician, Raymond Spritzler, ordered bed rest for his patient. But the irrepressible Wilder sneaked over to Lehman’s house one evening to confer about the script. Soon the doctor arrived at the front door for a house call, and Wilder scrambled into the nearest closet before Spritzler entered the bedroom. After the doctor pronounced Lehman fit enough to return to work, Lehman said, “Well, Doc, I guess I can tell Mr. Wilder to come out now.”34 Wilder said casually that doctors simply did not understand the demands of the picture business.

In late November, production chief Don Hartman instructed Wilder that, since he was already over schedule, shooting must be completed by the end of the week. Wilder still had one scene that had not been revised yet. It contained a long speech, full of fatherly advice, delivered by Fairchild the chauffeur (John Williams) to his daughter Sabrina as he drives her to the pier to board the Liberté for her sojourn in Paris. Wilder saved the unfinished scene for the final day of filming, December 5. He and Lehman started reworking it during their lunch hour and completed it around dinnertime. Fairchild’s speech was lengthy and complex, and Williams could not get it right. Legend has it that Wilder filmed seventy-two takes before Williams got his lines down; Wilder remembered only about half that many. At 9:30 P.M. Williams at last got the speech perfect, and Wilder exclaimed, “Cut! Print! That’s a wrap!”35 Wilder ended up eleven days behind schedule, with a final budget of $2,238,813, close enough to the original budget to elicit no complaints from the suits in the front office.

The picture begins with Audrey Hepburn as Sabrina introducing the film, in Wilder fashion, in a voice-over on the sound track. This prologue has the flavor of a fairy tale, prefiguring Sabrina as a Cinderella who is transformed into a graceful fairy princess by the time she returns from Paris: “Once upon a time, on the north shore of Long Island, some twenty miles from New York, there lived a small girl on a large estate. There was a chauffeur named Thomas Fairchild, who had a daughter named Sabrina. The Larrabees were giving a party . . .” The elflike Sabrina is perched in a tree, gazing dreamily at the couples waltzing on the Larrabees’ terrace to the strains of “Isn’t It Romantic?” Sabrina yearns to be a part of the Larrabees’ high life, but she is an outsider, watching their elegant ball from afar.

Later in the picture, David Larrabee whistles “Isn’t It Romantic?” as he encounters Sabrina on her return from Paris, just as Captain Pringle whistles the same tune when he is on his way to a rendezvous with Erika in A Foreign Affair.

A full moon shines above Sabrina as she sits on a tree branch, foreshadowing her father’s repeated warning, “Don’t reach for the moon, child.” But Sabrina is doing just that, since she is mooning over David Larrabee, the younger of the two Larrabee sons. David, however, is little more than a feckless playboy; he is annually listed on his brother Linus’s tax return as a six-hundred-dollar deduction. This is Sabrina’s last night on the Larrabees’ palatial estate; the following day she departs for Paris and a two-year course in a cooking school, arranged by her father.

By the time Sabrina returns from Paris, Cinderella has blossomed into a fairy princess, and David notices her; she is an intriguing mixture of sex appeal and innocence. She has eyes only for David, who is a jaunty, devil-may-care chap. By contrast, Linus appears to be a stuffy, conservative businessman. He carries an umbrella even on a sunshiny day, indicating that he is overcautious, afraid to take a chance even on the weather.

Sabrina wonders if she stands a chance in marrying David. “It’s like a Viennese operetta,” she reflects. “The young prince falls in love with a waitress in a cabaret, and his family tries to buy her off.” As a matter of fact, Linus, ever the hardnosed businessman, endeavors to railroad David into marrying Elizabeth Tyson, heiress to a sugarcane fortune, which is overseen by her father, played by silent film star Francis X. Bushman (Ben Hur, 1925). This lucrative marriage would prove beneficial to a Larrabee Industries business venture. Linus pretends to court Sabrina, ostensibly to get her mind off David. But Linus’s plan backfires when he begins to fall for Sabrina himself, and Sabrina eventually reciprocates his affection.

Wilder and Lehman agonized over the pivotal scene in which Sabrina meets Linus in the board of directors’ conference room late one night and they realize that they are genuinely falling in love. Wilder arrived on the set after lunch one Friday with only a page and a half of dialogue ready for this crucial scene. He nonchalantly sauntered over to Hepburn and asked her to stall the filming of the scene “by feigning a headache and fumbling her lines.”36 Hepburn was even willing to play the prima donna in front of the cast and crew by retreating to her dressing room for a nap. Her apparently erratic behavior enabled Wilder and Lehman to revise the scene over the weekend.

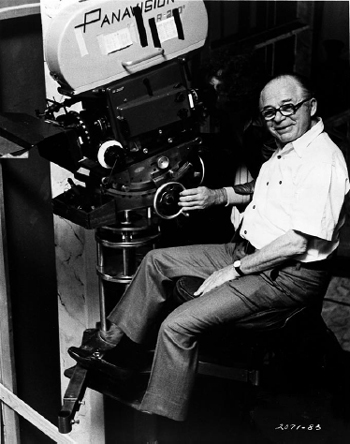

Billy Wilder on the set. (Author’s collection)

Greta Garbo and Melvyn Douglas in Ninotchka, which Wilder cowrote. It was directed by Ernst Lubitsch, Wilder’s mentor. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Don Ameche, Claudette Colbert, and John Barrymore in Midnight, which Wilder cowrote. It was directed by Mitchell Leisen, with whom Wilder clashed over script changes. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck in Ball of Fire, which Wilder cowrote. It was directed by Howard Hawks, a director whom Wilder admired. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

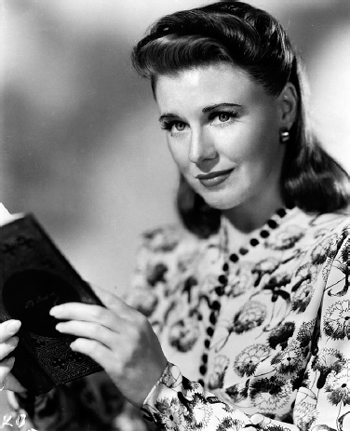

Ginger Rogers as Susan Applegate in The Major and the Minor, Wilder’s first film as a Hollywood director. Rogers in the course of the story had to disguise herself as twelve-year-old Sue-Sue and later as Sue-Sue’s mother. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Wilder, Erich von Stroheim, Anne Baxter, and Franchot Tone rehearsing Five Graves to Cairo. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Erich von Stroheim (center) as Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who was still leading the Nazi Afrika Korps when Five Graves to Cairo was made. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Miles Mander (Colonel Fitzhume), Wilder, Stroheim, and Ian Keith on the set of Five Graves to Cairo. Cinematographer John F. Seitz is behind Stroheim. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Writer Raymond Chandler and Wilder at work on Double Indemnity. Despite their fierce creative differences, they turned out a superior screenplay. (Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles)

Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity, a classic film noir. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson (Stanwyck) eavesdrops on Walter Neff (MacMurray) and Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) in Double Indemnity. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

MacMurray and Robinson in the scene that replaced the original ending of Double Indemnity. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Phillip Terry, Jane Wyman, and Ray Milland in The Lost Weekend. Milland won an Academy Award for playing an alcoholic. Wilder received Academy Awards for directing the film and coauthoring the screenplay. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Wilder clowning on the set of his Viennese musical, The Emperor Waltz. As for the film, critics were not amused. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Marlene Dietrich as Erika Von Schluetow, the former mistress of a Nazi officer in A Foreign Affair. Wilder had known Dietrich in Berlin in the 1920s. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Dietrich and John Lund (Captain John Pringle) in A Foreign Affair. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Cecil B. De Mille plays himself in Sunset Boulevard; Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond is seated behind him. (Movie Star News, New York)

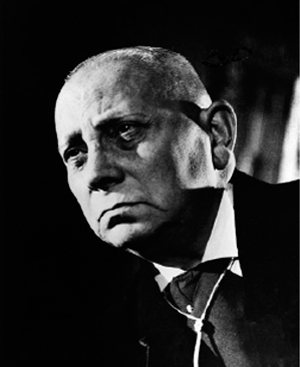

Erich von Stroheim as Max von Mayerling in Sunset Boulevard, the role for which he is most remembered. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Stroheim and Swanson in Sunset Boulevard. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

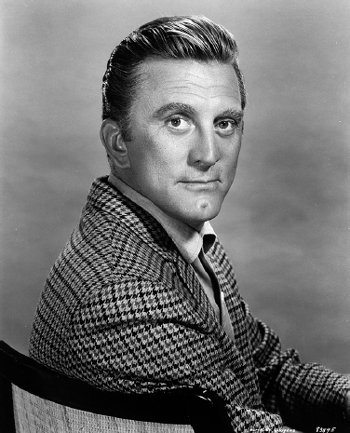

Kirk Douglas as Chuck Tatum, an opportunistic reporter, in Wilder’s exposé of “cheesy tabloids,” Ace in the Hole. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

William Holden won an Academy Award for his portrayal of J. J. Sefton, an inmate in a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp, in Stalag 17. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

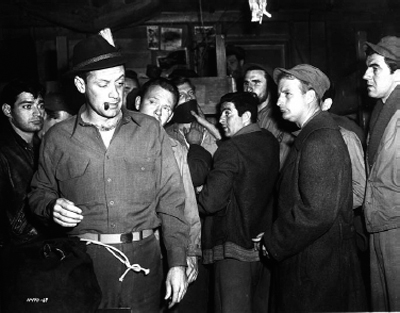

Colonel von Scherbach (Otto Preminger, center) views the corpse of a prisoner who attempted to escape from the POW camp in Stalag 17. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Wilder directs Otto Preminger, another director, as the commandant of the POW camp in Stalag 17. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Humphrey Bogart (Linus Larrabee) shares a toast with Audrey Hepburn (Sabrina Fairchild) in Sabrina. The tension between Bogart and Wilder was not evident in Bogart’s performance. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

This legendary photo of Marilyn Monroe with her dress billowing over a subway grating in The Seven Year Itch has been called “the shot seen round the world.” Tom Ewell looks on. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Audrey Hepburn (Ariane Chavasse) and Gary Cooper (Frank Flannagan) at the climax of Love in the Afternoon. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Charles Laughton) addresses the court on behalf of his client, Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power, far right), in Witness for the Prosecution. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Marlene Dietrich as Christine Vole in Witness for the Prosecution, testifying in court. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Tony Curtis as Joe/Josephine and Jack Lemmon as Jerry/Daphne in Some Like It Hot. (Cinema Book Shop, London)

Curtis and Lemmon in disguise as Society Syncopators. Marilyn Monroe (center) crowned her career with her performance in Some Like It Hot. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

George Raft (center) as racketeer Spats Colombo is confronted by Pat O’Brien as federal agent Mulligan in Some Like It Hot. Raft often played gangsters and O’Brien cops in gangster films of the 1930s. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine in The Apartment, the peak of Wilder’s career. Wilder received Academy Awards for directing the film, coauthoring the screenplay, and producing the best picture of the year. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Fred MacMurray discusses his role in The Apartment with the author. (Long Photography, Los Angeles)

J. D. Sheldrake (MacMurray) discovers that his secretary (Edie Adams) has been gossiping about his love affairs with the office staff in The Apartment. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

James Cagney (second from left) retired from the screen after making One, Two, Three. He is shown here with Horst Buchholz (right). (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Wilder reteamed Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine in Irma la Douce, his most commercially successful movie. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Dino (Dean Martin), Orville (Ray Walston), and Polly (Kim Novak) in Kiss Me, Stupid look over a ditty that Orville has composed. It was actually an unpublished song written by George and Ira Gershwin. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Walter Matthau won an Academy Award as Willie Gingrich, a crooked lawyer, in The Fortune Cookie. Here he badgers Ned Glass as Doc Schindler and Jack Lemmon as Harry Hinkle. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Sherlock Holmes (Robert Stephens) and Dr. Watson (Colin Blakely) in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, which was substantially cut before its release. This still is from one of the missing episodes. (Author’s collection)

Holmes pretends to be homosexual to fend off the Russian ballerina’s demand that he father her child. The ballet company’s impresario (Clive Revill) looks on. (Jerry Ohlinger’s Movie Material Store, New York)

Pat O’Brien as Hildy Johnson and Adolphe Menjou as Walter Burns (left photo) in the first film version of The Front Page (1930);

Jack Lemmon as Hildy and Walter Matthau as Walter (right photo) in Wilder’s remake (1974). (National Center for Film Study, Chicago)

Wilder, on the set of The Front Page, analyzes a comedic point for Matthau and Lemmon. (National Center for Film Study, Chicago)

Wilder gives Lemmon the proper nuance for an upcoming scene in The Front Page. (National Center for Film Study, Chicago)

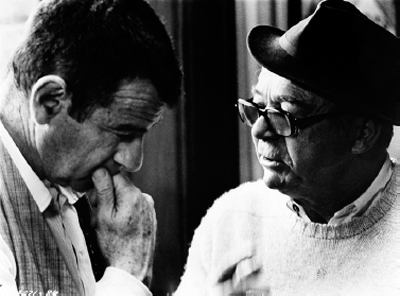

I. A. L. Diamond (left) on the set of Avanti! with Wilder. Diamond and Wilder cowrote a dozen films. (Film Stills Archive, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Marthe Keller, in the title role of Fedora, confers with William Holden as Barry Detweiler, a failure in the picture business, recalling his role in Sunset Boulevard. (Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Los Angeles)

Walter Matthau ponders Wilder’s direction on the set of Buddy Buddy, Wilder’s last film. (Bennett’s Bookstore, Hollywood, California)

Wilder received the coveted Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, one of the several life achievement awards bestowed on him in his later years, at the Academy Awards ceremony in 1988. (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills, California)

When Monday rolled around, Wilder was prepared with the script pages, and the scene came off very smoothly. Bogart played Linus as the self-sufficient, middle-aged bachelor who is forced to acknowledge his need for love, and Hepburn brought out the charm and gentleness in Sabrina that attracted Linus. The important scene was written and acted with exceptional finesse.

Linus is ashamed that he initially romanced Sabrina for an ulterior motive. Consequently, he encourages her to return to David. Sabrina, however, decides that she is fed up with both of the Larrabee brothers and opts to take the Liberté back to Paris. At the finale, David confronts Linus in the conference room and insists that he will not take Sabrina back because she is a gold digger who has plotted to marry into the Larrabee fortune. Outraged, Linus slugs David, who falls backward and somersaults all the way down the long conference table. “You are in love with her!” David proclaims; “I was just helping you to make up your mind!” Linus’s kayoing David is a nod to Bogart’s screen image as a tough guy. David hands Linus his hat and cane and tells him to rush down to the dock and board the Liberté before the ocean liner sets out for the open sea. Once on board, Linus joins Sabrina on deck and tells her the ocean voyage will be their honeymoon. As for his taking David’s place in her life, he reflects, “It’s all in the family.”

By the time Sabrina premiered in September 1954, Audrey Hepburn had collected an Academy Award. Hence the cast of Sabrina was headlined by three Oscar winners: Holden for Stalag 17 (1953), Hepburn for Roman Holiday (1953), and Bogart for The African Queen (1951). Sabrina was hailed by the critics as a charming and hugely entertaining love story; Frederick Hollander’s dreamy score and Charles Lang’s slick visuals were the icing on the cake. Hepburn was toasted as the alluring Sabrina that the story was waiting for.

Although Bogart still had nothing but scorn for Sabrina, Schickel points out that “the pictures he made thereafter are best left in something like near silence.” Sabrina was the last blockbuster in which Bogart appeared before he retired from the screen in 1956. His final five movies lacked “the livewire energy” of Wilder’s stylish high comedy.37 Bogart succumbed to cancer on January 13, 1957. Lauren Bacall phoned Wilder shortly before the end to say that Bogie wanted to see him. Bogart wished to be reconciled with Wilder, and he apologized for his ill-tempered behavior while making Sabrina. Wilder replied generously, “There is nothing to apologize for; we don’t have court manners around a movie set. I fight with a lot of people.” Wilder always thought of Bogart afterward as a brave man because he endured his last illness “with great dignity.”38

It goes without saying that Lehman did not wish to collaborate with Wilder again anytime soon. Sabrina “began in disarray and finished in sheer panic,” he commented.39 When I spoke with Lehman, he reflected, “Billy always got his own way. Somehow Sabrina turned out the way he wanted it to, and I never figured out how he did it.”

Sabrina was the last picture in Wilder’s current contract with Paramount; he decided not to renew his contract but rather to leave the studio. After eighteen years and seventeen pictures at Paramount, he believed it was time for a change. Once Sabrina had been launched, Wilder drove his Jaguar through the Paramount gate at 5451 Marathon Street, never to return. He was looking for fresh challenges at other studios.

Wilder was not interested in signing a long-term contract with any one studio, as he had done at Paramount. Instead, he preferred to make a deal with a major studio for one picture at a time. Each studio would arrange the financing and distribution of the film he made for it. Wilder set up shop as an independent producer-director. He would now exercise more control over the screenplay, the casting, and the direction of each film he chose to make.

While he was shopping around for his next property, Wilder was contacted by Irving “Swifty” Lazar, a Hollywood agent. Lazar had earned his nickname from the speed with which he could put together a production package for a studio. He informed Wilder that George Axelrod, the author of The Seven Year Itch, a smash Broadway hit, would like Wilder to consider directing the film version. The play had premiered at the Fulton Theatre in New York on November 20, 1952, and it went on to run for 1,141 performances. There was little risk in choosing to film The Seven Year Itch; it seemed almost guaranteed to be a blockbuster movie. The story is set in New York City during a boiling hot summer. Asked what attracted him to the play, Wilder said of the heroine, “The girl keeps her underwear in the frigidaire! Wow!!”40

The story centers on Richard Sherman, a middle-aged man who becomes infatuated with a woman who lives in the same apartment building while his wife and son are away for the summer. (Because The Seven Year Itch is a May-December romance like Sabrina, Wilder had Linus Larrabee arrange to take Sabrina to see The Seven Year Itch on Broadway.) When a Hollywood reporter parodied the title of the play The Seven Year Itch as “The Lust Weekend,” Wilder was convinced that the project was made to order for him. Charles Feldman, who had produced the film version of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), was now producing at Twentieth Century–Fox. Feldman, who was also an agent, had arranged to buy the film rights for The Seven Year Itch from Axelrod for five hundred thousand dollars as a vehicle for Marilyn Monroe, one of his clients.

Wilder, along with George Cukor and Joseph Mankiewicz, was one of the few directors Monroe was willing to work with, and she very much “wanted to work with Wilder on The Seven Year Itch,” notes Barbara Leaming.41 Since Monroe had an exclusive contract with Twentieth Century–Fox, Wilder would have to make the picture there. Lazar brokered a deal with the studio for Wilder to direct the movie, cowrite the screenplay with Axelrod, and coproduce the film with Feldman. Darryl Zanuck, the Twentieth Century–Fox studio chief, earmarked $250,000 for Wilder as director, cowriter, and coproducer of the picture—the same salary Wilder had gotten from Paramount for Sabrina.

When Axelrod reported to Wilder’s office at Twentieth Century–Fox for their first story conference in April 1954, Wilder began ribbing him from the get-go, just as he had done to the long-suffering Ernest Lehman on Sabrina. Axelrod had brought a copy of his play along, tucked under his arm. “I thought we might use the play as a guide,” he said. Wilder took the play and dropped it on the floor, replying, “Fine; we’ll use it as a door-stop.”42 Wilder’s insults had offended other writers Wilder had worked with. But Axelrod merely shrugged off Wilder’s barbs: “He sees the worst in everybody; but he sees it funny.”43 So the partners got along just fine.

Moreover, Axelrod did not believe he had much cause for complaint about Wilder’s plans to alter his play for the screen. Wilder assured Axelrod that he would retain the fundamental narrative structure of the play and as much of Axelrod’s original dialogue as the censor would allow. “For Billy I had awe,” Axelrod remembered; “I didn’t stand up to him” the way that Lehman had.44

The action of the play is limited to a single room in Richard Sherman’s apartment, but Wilder decided to open out the play for the screen by having a composite set of the whole apartment constructed. In this fashion Wilder could move the action throughout the apartment. In addition, he decided to play some scenes outdoors, to avoid the charge of merely making a “photographed staged play.” Wilder solved the problem of having a lengthy scene played in the same setting, such as in Richard’s living room, by never allowing the pace of the action to slacken during the scene. Moreover, he gave the scene variety by covering all aspects of the action from various camera angles.

The principal problem Wilder and Axelrod encountered in adapting the play for film was coping with the industry censor. In the play, while Richard’s wife Helen and his obnoxious son Ricky take a seaside vacation in Maine, Richard must stay behind in New York and endure the scorching heat. Nonetheless, he looks forward to his newfound freedom as a “summer bachelor.” After seven years of marriage, Richard has developed an itch to have a fling. Specifically, Richard yens for the blonde who has sublet the apartment above his in a Manhattan triplex for the duration of the summer. He invites her to his apartment with seduction on his mind. Significantly, Richard refers to her as the Girl, implying that, to him, she is a nameless, ethereal goddess who seems just beyond his reach.

Axelrod said that he and Wilder had “a horrible problem . . . with the Breen office” in developing the play’s spicy plot for the movie version.45 In fact, Geoffrey Shurlock had replaced Joseph Breen as film censor a few months earlier, and so it was with Shurlock, not Breen, that Wilder had to negotiate. To begin with, Shurlock contended that adultery was not an appropriate topic for comedy. Adultery had reared its ominous head in Double Indemnity too, but that was no comedy. In the stage play, Richard does in fact have an extramarital affair with the Girl. But the industry’s censorship code would not permit Richard’s flirtation with the Girl to be consummated in the movie. Wilder and Axelrod were forced to substitute fantasy sequences in their screenplay in which Richard imagines that he seduces the Girl.

Wilder had hoped at least to hint that Richard did have a sexual encounter with the Girl. “I remember spending a night wondering what to do,” and he finally came up with a solution to the problem. He went to Zanuck and said, “Try this: The maid of Richard’s apartment is making up the bed and finds a hairpin.” Wilder concluded, “And you know that they have committed the act.”46 But Zanuck refused to consider the idea, fearing that Shurlock would reject it too. Hence Wilder complained that he was straitjacketed in adapting the play for the screen: “The Seven Year Itch is a film about adultery, but the narrowminded morals of the 1950s made sure the climax only took place” in Richard’s overheated imagination.47

Wilder sent the completed screenplay, dated August 10, 1954, to Geoffrey Shurlock. (He had vowed never again to go into production with a rough draft of the script, as he had done with Sabrina.) Shurlock objected to some naughty phrases cropping up in the script that were prohibited by the censorship code. He took exception, for example, to the Girl’s line, “I feel so sorry for you with those hot pants.”48 Wilder contended that she was referring to the summer heat, not the heat of passion. Besides, Wilder maintained, some of the words and phrases that Shurlock considered improper for the film proved quite acceptable to theater audiences when they were spoken from the stage. As Axelrod put it, “We managed to bring the play in unscathed,” meaning that there were no censorship problems with the dialogue in the Broadway play.49 But Shurlock was intransigent, so phrases like “hot pants” disappeared from the movie’s dialogue. Be that as it may, Wilder had a knack for saucy innuendo, which he had learned from Lubitsch, so the script as approved by the censor was “still able to offer moments of risqué dialogue.”50

While casting the picture, Wilder was looking very hard for a suitable leading man to play Richard Sherman. He tested a young actor named Walter Matthau, who he thought was hilarious in the part. But Matthau was not as yet a star, so Zanuck insisted that they go with Tom Ewell, who had originated the role of Richard on the stage. “He knows where all the laughs are,” said Zanuck.51 Feldman, Wilder’s coproducer, agreed with Zanuck, so Ewell was cast. Matthau, however, was destined to make his name as a major actor in other Wilder pictures, starting with The Fortune Cookie.

Wilder and Feldman were in harmony on the rest of the casting. Evelyn Keyes (The Jolson Story, 1946) was given the role of Richard’s wife, Helen. Robert Strauss, who was selected to play Kruhulik, the superintendent of Richard’s apartment building, “offers only a slightly more articulate version of his ‘Animal’ in Stalag 17.”52 The director of photography for this picture, Milton Krasner, had just filmed Jean Negulesco’s Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) in CinemaScope and color.53 When this wide-screen process was introduced in the early 1950s, director George Stevens quipped that “the dimensions of the widescreen were better suited to photographing a boa constrictor than a human being.”54 But Wilder was committed to wide screen as well as color for this film.

The CinemaScope process was not particularly useful in the scenes set in Richard’s apartment. Wilder employed it to better advantage in the fantasy sequences, as when Richard dreams of making love to the Girl on an expansive seashore. Wilder quickly learned that the first rule of utilizing the format was that, if the action in the center of the frame was blocked out properly, the action taking place on either side would pretty much take care of itself.

Principal photography began on location in New York on September 3, 1954, and ran for two weeks. “Personally, I would prefer to shoot in the studio, because I am in control,” Wilder observed years later.55 After all, when shooting occurred in a real location, crowds of onlookers often flocked to watch the filming and got in the way. That is just what happened when Wilder was filming in the streets of Manhattan. One location scene takes place when Richard and the Girl are strolling on a sidewalk in downtown Manhattan on a hot summer night. The Girl finds the heat too much for her and decides to cool off by standing over a subway grating. As Douglas Brode describes the scene, “A train rumbles beneath, blowing the cool air upward,” and sends the Girl’s skirt fluttering to reveal her gorgeous legs. “Laughingly, she struggles—but not too hard—to keep it down as Richard looks on, his mouth hanging open like a hound dog’s.” It is in scenes like this one, Brode concludes, that Monroe proved herself to be the most authentic blonde bombshell to hit the screen since Jean Harlow.56

Sheer pandemonium resulted when this scene was filmed on location. Wilder had chosen to shoot it at the corner of Lexington Avenue and Fifty-second Street in the wee hours, when presumably the streets would be deserted. But Harry Brand, Twentieth Century–Fox’s intrepid publicity chief, planted a notice in the newspapers of the metropolitan area that Marilyn Monroe would be filming at the site at two o’clock on Thursday morning, September 15. Consequently, nearly two thousand fans were on hand to watch the Hollywood superstar do the scene. The milling crowds were kept behind barricades, but they nevertheless were noisy and unruly.

Wilder called out, “Roll ’em!” and a train passed underneath one subway grating—actually a wind-blowing machine manned by a special effects technician. The gust of wind sent Monroe’s billowy white dress flying above her shoulders, accompanied by raucous cheers from the gawking bystanders. “The scene wasn’t working,” Wilder remembered, so “we reshot it several times” over the next three hours.57 Each time Marilyn’s skirt blew upward, the spectators roared like the crowds at the Roman circus. Joe DiMaggio, Monroe’s husband, was among the onlookers. She had been married to the legendary New York Yankees baseball hero for eight months, and their marriage was already on shaky ground. DiMaggio was outraged at what he considered his wife’s indecent display. One of his friends, who was boozed up, said to DiMaggio, “Joe, what can you expect when you marry a whore?” DiMaggio yelled in response, “I’ve had it!”58 After the next take, DiMaggio whispered something in Monroe’s ear and marched away in a huff. Asked if her husband’s angry departure had worried Monroe, Wilder replied, “No; she loved the crowds”; she was at heart an exhibitionist.59

Nonetheless, when Monroe returned to hotel suite 1105 at the St. Regis Hotel a couple of hours later, she had to pay the piper. She and DiMaggio had a horrendous quarrel, with DiMaggio denouncing the crass exhibition his wife had put on. Cameraman Milton Krasner, who was trying to sleep next door, “heard shouts of anger through the wall.”60 As a matter of fact, “within hours after the famous scene was shot,” writes Fred Lawrence Guiles, Monroe’s first biographer, “the marriage was over.”61 Two weeks later, Monroe filed for a divorce. When DiMaggio’s friends told him that he had overreacted on the night when the controversial scene was filmed, he said, “I regret it, but I cannot help it.” DiMaggio, who had been brought up in a morally conservative Catholic home, was convinced that the skirt-blowing scene had publicly humiliated him. “I would have been upset if I had been her husband,” said Wilder in DiMaggio’s defense, considering the raucous comments that were being made that night by some of the bystanders, including one of DiMaggio’s friends.62

Tom Wood, among other Wilder biographers, believes that “Billy was perhaps indirectly responsible” for the breakup of Monroe and DiMaggio’s marriage because he shot the scene in which “a blast of air sent her skirt soaring.”63 Wood seems less than fair to Wilder. The director believed that DiMaggio had for some time nursed ambivalent feelings about being married to a movie star–sex symbol. “I don’t know if he was jealous of other men” giving his wife the once-over or “jealous of her getting more attention than he did. Probably both.”64

Leaming states baldly that the sequence filmed on Lexington Avenue was nothing more than “a spectacular publicity stunt,” since the footage had to be largely reshot in the studio.65 As Wilder pointed out, however, he had every intention of using the material he filmed that night, until he discovered that much of the footage was unusable because of the chaotic conditions in which it was filmed. What’s more, the censor was nervous about the sexual implications of the scene and would not approve the location footage because Monroe’s skirt blew up past her waist. After all, Shurlock emphasized, the script states merely that “a subway train roars by, the breeze from it blows her skirt a little” (emphasis added).66 Therefore, after the film unit returned to the Twentieth Century–Fox Studios in Hollywood on September 17, Wilder said, “We constructed a corner of the street on the back lot; and it was perfect.”67 George Axelrod added, “We used the original location shots of Marilyn,” which were more revealing than what was filmed in the studio, “in the ads.”68

Shooting would continue on the soundstages at Twentieth Century–Fox throughout the rest of September and into October. As always, Wilder worked out in advance with Doane Harrison how he would compose the shots and select the camera angles for each scene.

Monroe had an acting coach, Paula Strasberg, the wife of Lee Strasberg, the director of the Actors Studio in New York. Monroe leaned heavily on Paula Strasberg and demanded that she always be with her on the set. Hence Strasberg hovered over Monroe and was off camera giving her signals while Monroe was filming a scene. Wilder resented Strasberg’s intrusive presence on the set, and he saw it as an obvious sign of Monroe’s insecurity as an actress. But the front office had approved this arrangement, so Wilder had to put up with it. Still, he was frustrated by Monroe’s unprofessional behavior during the shooting period. Her growing psychic instability made her increasingly difficult to deal with; it was manifested especially in her chronic habit of showing up several hours late and not knowing her lines when she finally did report for work.

Howard Hawks, who directed Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, agreed with Wilder that Monroe had an inferiority complex about her acting ability. “She had to be convinced that she was good,” Hawks said. He remembered not being able to find her one day when it came time to shoot a scene. After looking everywhere, it occurred to him to lift up a table in the corner of the soundstage, “and there she was, hiding like a frightened girl.”69

It was not surprising that, by October 21, the movie was nine days behind schedule. It was largely Monroe’s fault. Wilder observed that “she had trouble concentrating because there was always something bothering her.” Understandably, “she was on the edge of a deep depression” because of the collapse of her marriage to DiMaggio.70 As her tensions grew, the dosage of her sleeping pills increased, and she started mixing her medication with alcohol. Leaming writes that, as time went on, Monroe “built up a tolerance to medication, driving her to ever larger doses.” Some days she showed up on the set in a groggy or dazed state. She sometimes seemed disoriented and would stumble over the simplest lines of dialogue. In short, she was a “sick, mixed-up girl.”71

Wilder now looked back nostalgically on his quarrels with Bogart while making Sabrina. “At least Bogart was there on time; and he was there all day,” Wilder mused. He endured such agonies while working with Monroe that Bogart seemed “amiable” by comparison.72 Wilder was convinced, however, that “it was worth going through hell” while making fifteen to twenty takes with Monroe because, when she finally got it right, “it was the best it could be.”73 Wilder found that, once Monroe finally emerged from her dressing room, he could work with her effectively. In fact, he managed to elicit a very good performance from her in The Seven Year Itch.

The production at long last wrapped on November 4, 1954, thirteen working days over the original thirty-five-day schedule, and more than $1 million over budget—mostly thanks to Monroe’s erratic and unpredictable behavior. So Wilder got going on the editing of the footage posthaste. Because he had planned the editing of the film with Harrison while shooting the picture, the two of them, plus editor Hugh Fowler, accomplished the final edit in record time.

Only one obstacle surfaced during postproduction: Wilder had to cope with the Legion of Decency, a Roman Catholic organization that rated the moral suitability of movies for its Catholic constituency. “Although the Legion was never officially an organ of the Catholic Church and its movie ratings were nonbinding,” Bernard Dick explains, “many Catholics were still guided by the Legion’s classifications.”74 In addition, in the absence of an industry rating system, which would not come to pass until 1968, the legion’s ratings were followed by many non-Catholics. The studio bosses tended to do the legion’s bidding to avoid receiving an objectionable rating from the legion for a movie, which would damage the film’s chances at the box office. The Seven Year Itch was Wilder’s first serious run-in with the legion. It would not be his last.

After the legion members attended a private screening of the movie, Monsignor Thomas Little, the legion’s director, registered a complaint with Twentieth Century–Fox. So Zanuck arranged for Little to meet with Wilder. The offending scene was one in which the Girl, while taking a bubble bath, gets her toe stuck in the faucet. A plumber (deadpan comedian Victor Moore) accidentally drops his wrench into the suds and has to feel around in the water to find it. When he retrieves it, he takes the phallic wrench firmly in hand. The plumber’s dropping the wrench in the bathtub is not in the shooting script, and therefore it must have been invented on the set. The screenplay merely says, “An elderly, shriveled plumber in overalls is trying to free her toe, working on the faucet with a monkey wrench.”75 Consequently, Wilder could not maintain that the gag the legion had found offensive was integral to the sequence. He grudgingly agreed to cut the shots of the plumber dropping the wrench in the tub and groping around in the soapy water for it. Still, The Seven Year Itch helped to pave the way for more artistic freedom in the making of Hollywood movies. “The picture could be done today without censorship,” Wilder opined years later; “one can now tackle more daring themes.”76

Wilder engaged Saul Bass, who was justly famous for designing the opening credits for many films, to create the title sequence for The Seven Year Itch. Recalling the old-fashioned French sex farces, in which a lothario is discovered hiding behind the closed door of a lady’s boudoir closet, Bass designed a patchwork of multicolored doors “that one by one slide aside to reveal the film’s credits lurking coyly behind them.”77

After the credits, Wilder forged ahead with a prologue for the movie that is nowhere suggested in the play. A narrator explains that it was the custom among the Native Americans on Manhattan Island “to send their wives and children upriver for the summer. . . . The husbands would remain behind to attend to business.” We see the Indian men, after they have loaded the women and children into large canoes, turn their attention to a sexy Indian maiden walking by. “Actually our story has nothing to do with Indians,” the narrator explains; “it plays five hundred years later. We only wanted to show you that nothing has changed in Manhattan; husbands still send their families away for the summer.” Richard Sherman puts his wife, Helen, and son, Ricky, aboard a train at Grand Central Terminal bound for Maine. He returns to his apartment to face another sweltering New York summer.

Richard soon encounters the Girl, who has sublet the apartment upstairs for the summer. In one of their chats she mentions that she is a model and also does TV commercials. The Girl later discovers a photo of herself in U.S. Camera and shows it to Richard. She calls it “one of those art pictures.” (This seems to be a reference to the nude photograph of Monroe that appeared as the Playmate of the Month centerfold in the first issue of Playboy in 1950. “All I had on was the radio,” Monroe recalled later.78) An explicit reference to the offscreen Monroe appears later in the movie when someone inquires about the identity of the vivacious blonde Richard has been hanging around with. “Wouldn’t you like to know?” Richard retorts. “Maybe it’s Marilyn Monroe!”

Richard is determined to remain faithful to Helen. (“I’m probably the most married man you’ll ever know,” he boasts.) Nevertheless, he fantasizes that he is a successful Casanova. In one of Richard’s daydreams, he pictures himself making love to a beautiful young woman on a sandy beach. His playmate emotes, “Richard, your animal attraction will bother me from here to eternity.” Louis Giannetti calls this fantasy a “delicious parody-homage” to Wilder’s old friend Fred Zinnemann, since it is modeled on a sequence in From Here to Eternity in which Burt Lancaster romances Deborah Kerr on the seashore. Richard’s middle-age spread, Giannetti adds, “presents an absurdly comical contrast to Burt Lancaster’s manly physique.”79

After he finally summons the courage to make his fantasies a reality, Richard invites the Girl down to his apartment for a drink. Before she arrives, he puts a recording of Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto on his phonograph, muttering, “It never misses.” The concerto conjures up a fantasy of Richard suavely sporting a scarlet smoking jacket and playing the concerto on the piano. The Girl, wearing an evening gown festooned with black stripes, struts around like a tigress in heat. But she is soon overcome by the strains of the lovely concerto, and she melts into Richard’s arms. They kiss passionately as the daydream fades. French filmmaker François Truffaut (The 400 Blows, 1959), who was a cinema critic before he became a director, wrote in his critique of The Seven Year Itch when it was released in France that Wilder, “the libidinous old fox,” parodies in this fantasy Brief Encounter, “the least sensual and sentimental film ever wept over.” Wilder’s movie, like David Lean’s, is “beyond smut and licentiousness” and treats the lovers “with good humor and kindness.”80

When the Girl really arrives, she notices Richard’s wedding ring and mumbles, “A married man won’t get drastic.” But Richard fully intends to get drastic. He uncorks a magnum of champagne, and the foaming liquid gushes out of the bottle—another phallic symbol supplied by Wilder, “the libidinous old fox.” Richard turns on his trusty Rachmaninoff recording, but the Girl shuns classical music—”No vocals,” she explains. In yet another of Wilder’s inexhaustible supply of baseball metaphors, Richard says, “Maybe we should send Rachmaninoff to the showers.” He invites the Girl to sit next to him on the piano bench while he tickles the ivories. He makes an abortive pass at the Girl; they topple over backward onto the floor. With sublime understatement, he says apologetically, “I’m afraid this wasn’t a good idea.” He politely asks her to leave.

Undaunted, Richard invites the Girl to take in a movie with him. As they stroll back to their apartment building afterward, the Girl casually mentions that she has just appeared in a TV commercial for Dazzledent toothpaste. “Every time I show my teeth on TV,” she says proudly, “more people see me than ever saw Sarah Bernhardt. It’s something to think about!” She adds that Dazzledent leaves her breath “kissing sweet” and demonstrates by kissing Richard full on the mouth. He returns the favor.

But Richard ultimately abandons his endeavor to become a swinging summer bachelor; seized by propriety, he decides to join his family in the boondocks of Maine. When he bids farewell to the Girl, she confesses in a speech that is not in the play that she is drawn to him because he is the “shy, gentle type” that she finds “tender and kind and sweet. . . . If I were your wife,” she concludes, “I’d be jealous of you.” Sarah Churchwell comments on the Girl’s perceptive observations about Richard, “She is not as dumb as some writers make out. The Girl is artless and unsophisticated; but she is not stupid.”81 The Girl gives Richard an affectionate good-bye kiss, and he dashes off to catch his train.

In April 1955, two months before The Seven Year Itch premiered, Marilyn Monroe was interviewed by Edward R. Murrow on CBS-TV. Monroe said, “One of the best parts I’ve ever had is in The Seven Year Itch. I knew when Billy Wilder wanted me for the part that it would be very important for my career.” She continued, “Billy Wilder is one of the best directors I have ever worked with. A good director contributes a lot when he is with you every moment on the set, helping you with your performance.” She added, “I enjoy doing comedies, but I would like to do dramatic parts too.”82

The studio brass decided to open The Seven Year Itch on June 1, 1955, Monroe’s twenty-ninth birthday, at Loew’s State Theatre on Broadway. DiMaggio accompanied Monroe to the premiere only as a publicity ploy, since they were already divorced. Twentieth Century–Fox had erected a blow-up of Monroe’s skirt-blowing pose on a billboard fifty-two feet high, which towered above the theater. When she saw the poster, Monroe grumbled, “That’s what they think of me.” She was tired of the image of the blonde bombshell that the studio had created for her. Monroe and DiMaggio showed up half an hour late for the movie—much to Wilder’s annoyance. “Marilyn made a grand entrance,” he complained, “thereby taking everyone’s attention away from my picture.”83 Still, there was a standing ovation at the end of the movie, which eventually grossed $5,734,471 worldwide. Zanuck had good reason to overlook the $1 million budget overrun.

The Seven Year Itch was enthusiastically received by reviewers as a sizzling sex farce beautifully mounted in CinemaScope. Milton Krasner’s cinematography is suitably lush, with bright reds and luminescent greens, befitting Richard’s garishly provocative daydreams. The Wilder-Axelrod dialogue delights in swerving off on unexpected tangents until the moment of truth is reached, while the plot is masterfully orchestrated throughout. The imaginative and inventive score was composed by Alfred Newman, head of the Twentieth Century–Fox music department. Because The Seven Year Itch is a romantic comedy, Newman’s fulsome melodies resemble the tunes one hears in elevators. It is particularly attuned to Richard’s florid fantasies.

The public adored Monroe in the picture, and she was never more radiant. Truth to tell, however, she was weary of playing sexpots that were none too bright. After Monroe completed The Seven Year Itch, “in a gesture of defiance against Fox, she went to New York and began attending acting classes at the Actors Studio,” under the direction of the Strasbergs.84 Twentieth Century–Fox lured her back to Hollywood in December 1955 with a lucrative contract that also gave her approval of the directors she worked with. Billy Wilder was on her short list of acceptable directors.

For his part, asked whether he would consider directing Monroe again after the anguish she had caused him while making The Seven Year Itch, Wilder replied that he was willing to forgive and forget. In The Seven Year Itch Monroe gave a fine-spun performance in one of her most appealing roles. Admittedly, “Marilyn Monroe was never on time; not once,” he concluded. “Of course, I’ve got my Aunt Ida in Vienna, who was always on time for everything; but who would want to see her in a movie?”85

Wilder would indeed work with Monroe again, a few years down the road; in the meantime, he had signed with Warner Bros. to make The Spirit of St. Louis, a movie about Charles Lindbergh. Axelrod shuttled back to Broadway with a play titled Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1955). And so it was that Wilder was looking for yet another collaborator on his screenplay.