First, let’s define our terms. For purposes of this book, our working definitions are:

These words date back to the 14th century and derive from petit, which means “small” or “minor” in Middle English/Old French. Numerous contemporary English-language dictionaries and thesauruses define the terms in similar but subtly different ways. These differences embody the nuances in petty behavior, further demonstrating the universality of pettiness as a phenomenon:

We might regard two 14th-century farmers squabbling over the rights to a pig’s lineage as petty (or petit), but back then the matter was probably incredibly important to them. Perspectives count—the personal as well as the etymological.

Today, we understand pettiness as a construct based on 20th-century theories of motivation and personality.

Today, we understand pettiness as a construct based on 20th-century theories of motivation and personality. Strap yourself in, because this chapter explores a number of psychological and psychoanalytical concepts essential for understanding petty behaviors. These include: neuroticism; emotional stability; stress and stressors; ability; motivation; valence; instrumentality; expectancy; outcomes; primal needs; social learning; self-image; conditional reasoning, affect; competencies; intelligence; personality traits and sub-traits; control; human behavior as quantifiable and predictable using replicable measurements; and a few more.

Using this background as a roadmap, we will arrive at our destination: a new theory of pettiness. Its four-quadrant model measures two key factors noted in the Introduction: the intensity of petty behavior, and the severity of outcomes associated with petty behavior. We’ll see how these four categories of pettiness—trivial, minor, major and significant—play out in real life, using actual examples from the workplace courtesy of your long-suffering peers.

Pettiness is an aspect of neuroticism, a concept that dates back to Freud and Jung, who were active from the early 1900s through the 1960s, and their successors in the field. Neuroticism is generally defined as emotional instability, especially in the form of behavioral responses to stressful situations.1 Several questions remain unaddressed by this definition: How much of a role do stressors play in manipulating personality? How are personality traits manifested in those responses? How does pettiness manifest itself in personality? To understand more, let’s take a look at how personality is conceptualized in the realm of psychology.

Psychologists have long identified two types of predictors associated with human behavior: ability and motivation.2 Ability predicts behavior so naturally that it is often expressed as a binary: one who has an ability to engage in a behavior is likely to be motivated to engage in it; one who lacks such an ability is unlikely to be so motivated and is unlikely to engage that behavior.3, 4 Motivation, however, is not so simple. The motives behind human behaviors vary as much as the theories of motivation that researchers have spent the better part of a century attempting to develop and codify.

Motivation, however, is not so simple. The motives behind human behaviors vary as much as the theories of motivation that researchers have spent the better part of a century attempting to develop and codify.

A chief example from the early days of theorizing on motivation is Expectancy Theory,5 which tries to codify why people behave in certain ways. Under Expectancy Theory, three variables determine motivation: (1) valence, or the value one places on desired outcomes; (2) instrumentality, or the degree to which one’s specific behaviors will lead to those outcomes; and (3) expectancy, or the likelihood of achieving those outcomes if one tries to do so (by engaging in those behaviors). The problem with Expectancy Theory is that it fails to predict how people arrive at their value judgments for each variable.6 What factors play a role in one’s determinations of value for valence, instrumentality or expectancy?

This failure led, for a while, to the resurgence of older theories of motivation.7 Needs Theory,8 for example, states that one’s primal needs for safety, belonging, esteem and self-actualization—the climb toward achieving one’s best view of oneself—explain one’s behaviors. This theory regards basic needs as predictors of people’s voluntary choices to act in certain ways, but it does little to explain why people behave in predictable ways toward others or how they make decisions about matters unrelated to their core needs.

Over the decades, researchers turned their attention from the theoretical to the applied perspective, attempting to use measurements to triangulate behavior prediction.9 By focusing on things that could be measured easily, they could treat motivation the way they treated ability. The first researcher to use the measurement approach at scale, Bandura, applied an edict of psychological research—“if you can measure it, you can predict it”—to Social Learning Theory.10

Social Learning Theory explains how people are motivated to learn based on their self-image. Bandura started measuring self-esteem, self-efficacy and locus of control—states of mind—to predict behavior. His work turned prediction on its head; researchers realized they could look at things without worrying too much about how those things were defined conceptually. It became easier for researchers to examine other perspectives and concepts related to motivation.11

Psychological researchers soon looked at conditional reasoning, affect and competencies as ways to predict human behavior.12 They took another look at ability, which had been considered the best predictor, breaking it into many different little pieces,13 or intelligences.14 They considered what the second-best predictor might be—personality traits? Or states of mind? In order to make human behavior known and quantifiable, the psychology profession was carving it apart.

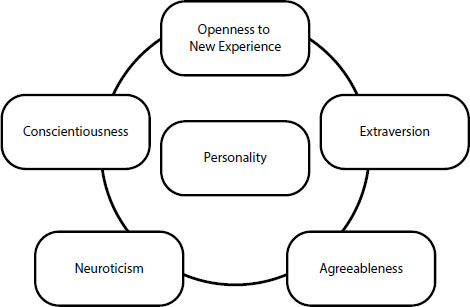

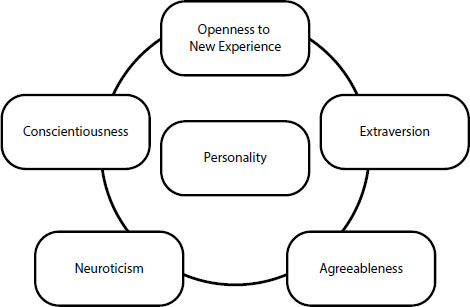

One group of researchers successfully made the claim that personality traits play a vital role in predicting behaviors.15 They conducted a meta-analysis (i.e., they aggregated the findings of all studies on the topic, correcting for artifacts that limited generalizability), and found a set of themes across disciplines—five immutable personality traits. The five traits could be defined easily, measured consistently, and utilized to predict human behaviors accurately. The resulting model, depicted in Figure 1.1, forever altered the way psychologists and other scientists conduct research into human behavior.

Over the subsequent 25 years, legions of researchers have explored the Big Five personality traits, disentangling each super-trait into smaller components.16 The Conscientiousness trait, for instance, consists of 16 constructs or sub-traits, ranging from dependability to boldness to remorse.17 The Neuroticism trait, however, has only two primary sub-traits: (1) general stability in the face of stressors;18 and (2) pettiness, defined most recently as the tendency to get agitated over trivial matters.19

Figure 1.1. The Big Five Personality Traits

Which brings us back to the subject of this book.

Seven hundred years after petty entered the vernacular, people are still “sweating the small stuff.”20 More evidence and increasingly refined conceptualizations in the professional literature prove that pettiness is a defining personality trait, which can predict human behaviors (such as social deviance and patriotism) as well as states of mind (such as depression and life satisfaction).21

Now there’s even a replicable way to measure pettiness consistently: a five-item scale has been developed to help identify the stressors most heavily correlated to pettiness. That gives me hope. Understanding these stressors—the antecedents to pettiness—can lead to a new way of understanding pettiness itself.

The body of research on pettiness provides us with an opportunity to redefine it. We can start thinking of pettiness as a potentially changeable state, rather than solely as an immutable trait. This will enable us to do more than identify petty people: we can change people’s petty ways.

The body of research on pettiness provides us with an opportunity to redefine it. We can start thinking of pettiness as a potentially changeable state, rather than solely as an immutable trait.

The established components of pettiness as a trait and a state are fairly important. But we have a moral imperative to describe pettiness in new ways that enable people to see it and stop it, thereby restoring civility.

Accordingly, I propose a new theory of pettiness as a behavioral motive, based on theories of expectancy plus an examination of the following two behavioral conditions or factors:

The model of the new theory, depicted in Figure 1.2, is based on some of the motivational theories outlined above. It is designed to help us understand how all petty behaviors fall into certain categories. Pettiness is redefined by the two newly identified dimensions of intensity and severity. The y axis measures the “intensity” of the petty behavior (from “simply offensive” to “vengefully malicious”) and the x axis measures the “severity” of the outcomes of the behavior (from “inconsequential” to “consequential”). Intensity and severity intersect to yield four quadrants, each quadrant a category of petty behavior.

Over the course of the last year, my research team and I have conducted a broad study to identify pettiness and how it manifests itself in the workplace. We consulted more than 15,000 business professionals from a wide array of industries and disciplines and asked them to share their stories of pettiness so that we could learn firsthand what they considered to be petty behavior. The participants described actual incidents and chose a category based on one of the quadrants of the model.

Figure 1.2. The Four-Quadrant Model of Pettiness

The four categories of incidents are:

What we learned was absolutely astounding, as you will see for yourself when you read the stories in the next chapters and review the findings of the 2019 SHRM Pettiness in the Workplace Survey at the end of the book.

Here’s what really jumped out at us from our research:

The big picture was no less surprising. First and foremost, it’s clear that pettiness abounds in all enterprises, like an endless negative energy source.

Second, pettiness takes many shapes and forms, which relates to third: people are extremely creative, both in the intensity of their petty behaviors and in how they interpret the severity of the outcomes of those behaviors.

People are extremely creative, both in the intensity of their petty behaviors and in how they interpret the severity of the outcomes of those behaviors.

Fourth, people want to eradicate pettiness, but aren’t always sure how to go about it. (Hint: the place to start is from within yourself; then with Chapter 8.) When there is no action taken in response to pettiness, its targets and witnesses eventually distrust their leaders and lose their morale—and the behaviors continue.

To discourage petty behaviors in the workplace, organizations must point them out and describe their effects. Management and HR can implement intervention techniques, such as individual coaching sessions and performance improvement plans. You’ll read about some of these organizational responses in the next chapters. You’ll also read about the substantial number of people who continued their petty behaviors, for whom the ultimate intervention was implemented: termination of their jobs.

Best lesson learned from this project: People are funny! Many of our survey participants apparently shared their experiences both as a means of catharsis and as an excuse to tell a wild tale. Some incidents rival the best shaggy-dog stories you’ve ever heard.

We painstakingly culled this dubious treasure trove down to the funniest, most interesting incidents of pettiness ever reported. We interviewed the reporters to gather more background and context. We double-checked their categorizations. Finally, we removed information that could identify the people and organization involved. All the stories you are about to read are true; they’re only missing names and some extraneous details. This was done to protect the storytellers as well as ourselves—not a petty consideration.

Additional fun fact: It only seemed fair to include a couple of stories recounting my own battles with pettiness. Enjoy trying to figure out which ones they are!

Chapters 2 to 5 recount actual stories of everyday, real-life petty behaviors in the workplace, as told by witnesses to the events or by the players themselves. Names, locations and other uniquely identifying details have been removed, but these anecdotes are 100 percent authentic.

Some accounts are cringeworthy, some are darkly amusing, some end on a positive note. But they are not surprising. All of us can recognize our own missteps in these tales; who among us has never succumbed to short-circuited thinking or done something just plain mean? Our fellow humans were there to see what happened, or they bore the brunt of it. They lived to tell the kinds of tales collected in these pages.

Practicing HR professionals were asked to share their stories so that we could learn firsthand what they considered to be petty behavior. The contributors work in a wide array of industries and disciplines across the U.S. and around the world, occupying positions at every level of authority and responsibility from intern to CEO. They were asked to categorize their incidents based on the intensity of the petty behavior and the severity of the outcome, as described in the Four-Quadrant Model of Pettiness introduced here.

Close to 300 incidents were compiled and compared for common threads and themes. We chose a representative sample of the issues that people encountered most often, and from that list culled the most interesting to feature in the book. We excluded incidents of behavior that was clearly illegal (but see Chapter 6) or subject to civil penalties.

In reviewing these incidents, we discovered that petty behavior is everywhere. It’s a worldwide problem that must be managed by organizations everywhere, every day. From the tales told herein, there are lessons to be learned.