“HUMANITY GONE MAD”

IN THE WEEKS BEFORE the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many Americans stopped by their local movie theaters to see the most popular film of the year, Sergeant York. The film depicted a pacifist, Alvin York, on the eve of America’s entry into World War I. York had grown up on a hardscrabble Kentucky farm; after his father’s death, he met a beautiful girl and became evangelized, making a personal commitment never to kill. When York was drafted he recalled he “was worried clean through. I didn’t want to go and kill, I believed in my Bible.”1 He applied, unsuccessfully, for conscientious objector status. At basic training camp, two officers who recognized York’s talent with a rifle and were also, apparently, persuasive interpreters of scripture convinced him that killing was sanctioned in the Bible if the cause was just. On October 9, 1918, York killed twenty-eight Germans and single-handedly took 132 prisoners in the infamous Battle of the Meuse Argonne.2

Sergeant York was promoted as a film about war, but a strikingly large percentage depicted York’s life on his Kentucky farm, perfect for the intended audience of the time: rural Americans, particularly those from the upper Midwest and Great Plains states, who had resisted both the expansion of the Spanish-American War and American entry into World War I. Throughout the 1930s these Populist anti-militarists—called “isolationists” by their critics—had fought passionately against American participation in a second conflict with Germany.3 True to fifty years of Populist-inspired politics, they believed that war only served to profit the rich and expand the power of the federal government. Some had seen for themselves the carnage of war and the distinctly undemocratic nature of military life. In the 1930s their congressional representatives sponsored laws, including three Neutrality Acts, to ensure the United States did not intervene in any new international conflicts. But by 1940, as Hitler marched through Europe and bombarded London, President Roosevelt became desperate to persuade Americans to change their minds. He turned to his “men in Hollywood.” By producing Sergeant York, and “a few [other] good movies about America,” Jack and Harry Warner and other studio owners set out to do just that.4

But how could a film depicting a rural man reluctant to go to war convince other rural men to go to war? First, filmmakers were careful not to lampoon rural life. Rather than a dirt poor and ignorant “hillbilly,” like the ones satirized in the popular cartoon, Li’l Abner, they portrayed York as a thoughtful man with essential moral goodness.5 The director also rejected pinup girl Jane Russell for the part of York’s sweetheart, casting instead a 16-year-old newcomer, Joan Leslie, who neither smoked nor drank. The film elevated rather than diminished rural experience. It suggested, for example, that York’s skill as a backwoods hunter helped make him an effective soldier—using a turkey gobble to entice Germans out of hiding, for example. Most importantly, the film showed that leaving the countryside and going to war did not change Alvin York. He returned to his sweetheart and his pacifism after the war. In 1940, when he saw the film for the first time, the real-life York apparently liked everything about it—except the killing.6

In the end, Sergeant York succeeded beyond the filmmakers’, or the president’s, wildest dreams. It earned more money than any other film that year, won two Academy Awards, and was nominated for nine others. Best of all, Sergeant York convinced many a reluctant warrior to fight—some going directly from the cinema to the recruiting station. According to historian Lynne Olson, “in the process of making the film” York himself “became a convert to interventionism”—again.7

However inspiring, Sergeant York still left many anti-militarists in the Dakota countryside unsettled. A small handful, like North Dakota senator Gerald Nye, remained unconvinced that war against Germany was necessary even after Pearl Harbor.8 They called the film “an instrument of propaganda” and studios like Warner Brothers “the most gigantic engines of war propaganda in existence.”9 Senator Nye complained that the film was unrealistic. It did not show men “crouching in the mud … English, Greek, and German boys disemboweled, blown to bits.”10 Populist anti-militarists saw in the film the growing power of the federal government to control information, media, speech, and even political beliefs when a crisis “required” it. They saw what they had feared for more than two generations, through World War I and the Great Depression: that the United States was becoming more like the militarized states of Europe with powerful, sometimes despotic centralized governments, and permanent standing armies where “it was impossible … to be both militarized and free.”11

Nye and many others from the Northern Plains knew a different story about what could happen to conscientious objectors during World War I. They also knew Warner Brothers would never make it into a film. Josef and Michael Hofer were young Hutterite men from the Rockport colony in southeastern South Dakota. Like York, the Hofers applied for conscientious objector status based on their religious beliefs and were denied. Unlike York, no officers could ever persuade them to give up their pacifist beliefs. They were what military officials called “absolutists.”12 In 1918 a military court sentenced the Hofers to twenty years’ hard labor at the notorious federal prison on Alcatraz Island. When they arrived and still refused to wear a military uniform, the Hofers were imprisoned in small basement rooms with wet floors and given little water and no food for the first five days. They were also “high cuffed”: forced to stand for nine-hour stretches chained with their hands above their heads and only their toes touching the floor. Both men died within days of being transferred to Fort Leavenworth. Only then did the US military succeed in putting uniforms on them—in their coffins.13

Dakotans themselves shared some of the blame for the Hofer boys’ fate. Before the war they had largely lived in peace with their religiously absolutist neighbors, finding common ground in the view that working the land was good and war was bad. When the war arrived, however, some Dakotans became as suspicious of Germanic Hutterite practices as the military authorities.14 A few local people stole Hutterite cattle, set fire to their barns, and attacked their leaders. They ultimately succeeded in cleansing the countryside of these radicals, newly seen as “un-American.” In 1918 residents of Rockport abandoned the colony, relocating to Canada. But the memory of these attacks only reinforced anti-militarist fears, even in those who perpetrated them. Having witnessed the militarization of their society in the late 1910s, Dakotans resisted war even more ardently in the 1930s. They asked, as Chicagoan Jane Addams had in 1917, “Was not war in the interest of democracy … a contradiction in terms, whoever said it or however often it was repeated?”15

* * *

The “political prairie fire” of Populism and its political descendants has long captured the attention of historians, even as they have debated whether its legacy belongs to the American left or right. But these same historians have largely overlooked the movement’s extension of its critique of concentrated power to the military. Over the course of three wars between 1890 and 1941, agrarian radicals—at times with the consent and cooperation of their conservative opponents—made undeniably clear their dedication to anti-militarism and their opposition to a permanent standing army.16 It was a defining element of their political tradition, which once alienated from economic agrarianism, left the region vulnerable to being militarized itself.

A cursory glance at the Omaha platform of 1892 might suggest that any discussion of the People’s Party’s foreign policy could be quick reading. Only a single “sentiment” mentions the military: “Resolved, that we pledge our support to fair and liberal pensions to ex-Union soldiers and sailors.” But the silence of Omaha platform and subsequent Democratic platform in 1896 about traditional matters of foreign policy also spoke volumes. Populists, like Alliance members before them and Midwesterners as a whole, were not unsophisticated rubes. They had a global perspective on markets and supported free trade. They certainly knew that global markets affected the price for crops and other agricultural commodities. A group of Kansas Populists even began its own colony on the west coast of Mexico.17 Likewise Populists in the late 1880s and 1890s knew full well of the Republican proposal to strengthen the navy and increase the United States military presence around the world, whether in Hawaii, Japan, China, or South America. Even so, they believed strongly that industrial-era economic transformations had to be ameliorated at home before any action could be taken abroad.18

As it did for many Americans, the Spanish-American War, which began with the media-enhanced “destruction” of the battleship Maine in Havana harbor, forced Populists to define their views on the American role in the world. David Lee Amstutz contends that Populists were “strongly opposed to empirical rule, or imperialism.” At the same time, they “accepted the idea of self-determination of nations, and they also thought fostering democracy would safeguard American security.”19 As a result, most Populist leaders supported the war in Cuba, expecting that a victorious US would grant Cubans full independence and would not pursue further imperialist adventures elsewhere. When conservatives in Congress advocated the annexation of Hawaii and the broadening of the war to the Philippines, Populists instantly lost enthusiasm for the war.20 Leaders from the Northern Plains, including William Jennings Bryan, Richard Pettigrew, and Andrew Lee, led the first Populist anti-imperialist movement in Washington and local capitals. As time passed and one war became another and then another, they learned both how difficult it was to fight against war—and to fight in one.

A national figure and a “godly hero” to many rural Americans even though he had come to Populism only through its decision to fuse with the Democrats in 1896, William Jennings Bryan’s views on war illustrate how rank-and-file Populists thought about war and imperialism. Throughout his life, Bryan believed that war-making was a violation of Christian principles. Moreover, his views on war overlaid his concerns about economic injustice, since, in his view, the upper classes profited from war while clerks and factory workers paid with their lives.21 Nevertheless reports of Spanish atrocities in Cuba and the loss of American life aboard the Maine convinced Bryan that the United States needed to intervene. He accepted the offer of a commission in the Nebraska National Guard and picked two thousand troops from the scores of local Nebraska residents, young and old, who had volunteered to fight with him. In the end, Bryan and his troops never saw battle in Cuba, stationed (he thought imprisoned) in Camp Cuba Libre in northern Florida for the duration. Bryan’s inactivity did not come from lack of commitment to the cause. Instead it reeked of political gamesmanship. Why would McKinley have given his rival an opportunity for glory during midterm elections if he did not have to?22 When Bryan finally resigned his commission and left to campaign again, he joked, “I had five months of peace in the Army and resigned to take part in a fight.”23

Fighting a limited war to “free” Cuba was one thing, but expanding it to the Philippines confirmed Bryan and his followers’ worst fears about McKinley’s original intent. They saw the war and subsequent treaty with the Philippines as nothing more than a naked imperialist land grab. Speaking to the Democratic National Convention in Kansas City, Missouri, in July 1900, Bryan argued that in light of the American tradition of self-government, colonization of the Philippines made hypocrites of all who called themselves lovers of freedom. He paraphrased Lincoln’s belief that our freedom does not depend on militarization: “the safety of this nation was not in its fleets, its armies, its forts, but in the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands, everywhere”; and he warned his fellow citizens that they could not “destroy this spirit without planting the seeds of despotism at their own doors.”24

Echoing George Washington’s concerns about “entangling alliances,” Bryan was most concerned about how the creation of a standing army would affect the politics and culture of the United States. Not only would a vastly expanded professional military require immense amounts of money, it would also change the culture of the peaceful land and its people: “The army is the personification of force, and militarism will inevitably change the ideals of the people and turn the thoughts of our young men from the arts of peace to the science of war.”25 For Bryan and his many followers, imperialism begat militarism, and it was militarism they feared most, however much they had benefited from their own military’s violent removal of Natives from the Plains.

Imperialists like Teddy Roosevelt and William McKinley were unlikely to take these criticisms lightly, especially when they came from such an esteemed figure. Rather than one-offs, however, their sharp responses foreshadowed attacks on anti-militarists throughout the twentieth century, including those who protested the war in Vietnam. They focused on anti-militarists’ patriotism. South Dakota senator James Kyle claimed in an interview to be “deeply grieved” by his colleague Richard Pettigrew’s “unpatriotic stand” on the war.26 But opponents also assailed Populist anti-militarists’ gender identities. As Kristen Hoganson has explained, they worked to make Populists and others who sought peace seem more and more out of the mainstream—not only of culture but also of gender.27 Populists, for example, were increasingly accused of being “old women.” Even the act of joining a third party (seen as an act of unmanly disloyalty) gave Populists the moniker of “she-men,” “eunuch,” and “man milliners.”28 In the presidential campaign of 1900, McKinley’s heroic Civil War record was held high, while questions raged about why Bryan had not stepped foot in Cuba. Later the Democrat Woodrow Wilson praised “the young men who prefer dying in the ditches of the Philippines to spending their lives behind the counters of a dry-goods store in our eastern cities. I think I should prefer that myself.”29 Of course, Populists feared the moral and economic consequences of militarism far more than they feared any kind of less “strenuous” future, and the campaign in the Philippines did nothing to dissuade them of this view.

* * *

Bryan was well-known in his day and is historically well remembered. Even so, it was not Bryan but the almost entirely forgotten (and Indian-artifact-collecting) Populist senator from South Dakota, Richard Pettigrew, who led the anti-imperialist forces in the Senate. In fact, even after Bryan had given up, Pettigrew fought against increasing the size of the military and expanding the military beyond North America. He resisted the annexation of Hawaii, the war in Cuba, and the annexation of the Philippines. In each of these cases, his views demonstrated how the economic and political concerns at the heart of the Populist movement—regulation of trusts and the power of corporations; protection of American farmers and workers; maintenance of white supremacy—informed, even determined, its anti-militarism. As Kenneth Hendrickson argues, Pettigrew and other Populist anti-imperialists were “convinced that the plutocrats of Wall Street sought overseas frontiers for exploitation, and that the vehicle through which they worked was the Republican Party.”30 They were countered with the full ire of that party; in 1900 it coughed up a half million dollars to defeat him. Infuriated, he wrote an ally: “These fawning sycophants without brains who act as McKinley’s advisers are disgusting in the extreme. They want to carry out the idea that their President is a sort of emperor and that loyalty to him is the only way of expressing loyalty to flag and country.”31

Pettigrew took on the annexation of Hawaii first. This was nothing more, he claimed, than a deceptive play by the “sugar trust” to decrease competition and increase profits. As a Populist, he was against all trusts, of course. But this one hit home, as small farmers on the Northern Plains were trying to harvest sugar beets. He also perceived the hand of the American capitalist elite at work in the Hawaiian revolution, which had quickened calls for annexation. The first constitution for the government allowed for wealthy property owners alone to serve as elected officials or to vote. To Pettigrew this indicated just one thing: “They established an oligarchy.”32

Pettigrew also wondered why the military needed to expand naval bases into the Pacific, which Hawaiian annexation would allow. To him and many other Populists, an expanded military merely allowed large corporations to increase their monopolies and profits. After all, who would profit from a major expansion of American sea power? The steel trust. Hendrickson explains, “Pettigrew viewed domestic exploitation and expansion as one and the same conspiracy, thinking that imperialism was merely a sham to increase the need for military spending … and increasing government purchases of armor plate from the steel trust.”33 Pettigrew supported the effort of the US military to “free” the people of Cuba from Spanish dominion.34 But he also saw the naval vessels sunk in that conflict and needing replacement as yet another way in which expansionists could press for a larger military presence around the world. Last, he accused the military of dishonesty, of firing the first shot and then denying it.

Pettigrew’s partner in Populist anti-militarism and anti-imperialism at home in South Dakota was Governor Andrew Lee. Once the war was declared, Lee had to muster troops and pay for them. As it happened, he was already struggling to cover state expenditures, since two years before, corrupt administrators had raided the state treasury. Lax taxation of railroads and the 1890s recession had also left South Dakota coffers nearly bare.35 Even so the federal government asked for the same number of troops—one thousand—from new states in the West as it did from long-established states in the East. Lee complied and mustered the First South Dakota Volunteer Infantry in May 1898. Its members arrived in Hawaii just in time to shake the hand of the new American governor, Sanford Dole, before heading to the Philippines. While the war with Spain was officially over when they arrived, the First South Dakota was nevertheless put to work fighting insurgents in the Filipino jungle.36

Governor Lee’s troubles had just begun. Lee was shocked that the government would use the First South Dakota in an action that had not been authorized by Congress, or by him.37 True to his Populist perspective, writes R. Alton Lee, he also claimed that “any further use of the troops would only benefit capitalists.”38 McKinley thought little of Populists, of course, and less of their concerns about imperialism. The South Dakota soldiers fought on for 126 days, facing illness, injury, and death in a land unimaginably different from their homes on the Northern Plains. When his troops finally landed in San Francisco, Lee discovered the federal government had no intention of paying for the rest of their journey home, which cost the state $27,000.00. The bill was eventually repaid, sort of. After suing the federal government, South Dakota received $15,573, less a 20 percent attorney’s fee.39 Far from the Populists’ ideal of an empathic, “people first” state, the American government seemed as eager to steal their money as banks and corporations.

Local politics further complicated Lee’s and Pettigrew’s reactions to war. Melvin Grigsby lost the Populist nomination for governor and served a contentious term as attorney general, including what Lee called “scandalous conduct on board of a sleeping car on a trip from Pierre to Huron.”40 With the outset of war, however, Grigsby wondered how service in war might improve his political position nationally. Grigsby, well-known for having escaped from two southern prison camps during the Civil War, mustered a volunteer force of horseback riders from several Northern Plains states, calling them “Grigsby’s Cowboys.” But unlike Theodore Roosevelt’s famous Rough Riders, Grigsby’s cowboys never made it out of camp in Chickamauga, Georgia. Far worse than the frustration men felt at seeing no combat was the poor sanitation, water, and food. Several men died of disease, when they were ordered to stay in camp even after the war in Cuba had ended. Hundreds of members of the soldiers’ families wrote to Lee and Pettigrew demanding that the soldiers be mustered out. They couldn’t understand why Grigsby would make his men stay. Lee and Pettigrew suspected that Grigsby was considering switching to the Republican Party so that McKinley could promote him to brigadier general or endorse him for Pettigrew’s Senate seat.41 When the South Dakota “cowboys” finally headed home, Lee wrote, “doubtless [Grigsby would] have allowed the boys to remain there until they were all dead in order to draw his salary.”42

Even though their political leaders were skeptical, ordinary young Dakota men were excited to join the war effort. Echoing advocates of the “strenuous life,” conservative newspaper editors stressed the opportunity of war to make South Dakotans more “virile.” The Rapid City Journal, for just one example, reminded readers that “many a man was made in the war of the rebellion.”43 As happy as they were to take on the manly pursuit of soldiering, South Dakotans nevertheless discovered that democracy and self-governance ended at the muster tent’s door. Upon arrival in Sioux Falls to join the First South Dakota, many discovered that “Uncle Sam’s” rations were not exactly home cooking and, worse, as Herman Krueger of Lake Country put it, were “carefully doled out, no help yourself.”44 The men resented the absolute authority of elite officers—who often enough were dangerously incompetent. Krueger wrote again and again to his brother about such concerns. He began by telling of the officers who chose a spot well-known to flood to make camp. It flooded. He also told about the time when the officers built a privy so unstable that several men fell in. The final straw was when the officers transported an injured man by dray rather than ambulance and the jostling caused him to bleed to death.45

Krueger and Thomas Briggs of Mitchell, South Dakota, also observed that militarization literally demoralized some of their companions. Briggs was surprised to learn, for example, when he was on board a ship to Hawaii, they had no “Sunday services” and that some men played cards to pass the time instead. In Manila, Briggs commented that many men were openly attracted to “the Spanish ladies, some of them extremely handsome, bareheaded [and] dressed in the light gauzy fabric proper to the climate.”46 Krueger was angrier about the hardening of character he saw as a requirement of military service. This desensitization became much worse after months fighting insurgents in the jungle. Krueger was shocked by the attacks some infantrymen made on native Filipinos, including prisoners.47 He concluded in one of his last letters home, “Grant said ‘war is hell.’ It is. May God save our home country from war.”48

* * *

As the “lamps” went out “all over Europe” in August of 1914 and the “Age of Catastrophe” began, voices of resistance to militarism in the United States gathered strength across the country.49 By 1914, as historian Michael Kazin describes, a complex and “ever-widening circle” of socialists, pacifists, feminists, anti-imperialists, immigrants, Southern Populists, and Midwestern Progressives had come together from every region in the country to create the “largest, most diverse, and most sophisticated peace alliance to that point in US history.”50 Moreover, the strength of the coalition and the unwillingness of some of its members to end their resistance to the war once it had been waged provoked the strongest state repression of dissent in our history thus far, presaging the “surveillance state” so familiar in the post-9/11 world. The well-known struggle against radicalism that followed the First World War—and would also follow the Second World War—began with a crackdown on Americans who stood against war itself.

Among the most influential of the anti-war groups were those whom Kazin calls “Midwestern progressives”—Republicans Robert Lafollette and George Norris, and the Democrat William Jennings Bryan. By 1915 Bryan had failed twice more to become president, but became secretary of state under Woodrow Wilson. His principled anti-militarism, informed by his Christian worldview, hardly diminished as the war intensified. Bryan’s reluctance to give aid to the Allies even after the sinking of the Lusitania isolated him in Wilson’s cabinet and ultimately cost him his post. But it barely diminished his support in the upper Midwest: after tendering his resignation, Bryan received hundreds of letters of support from farmers, workers, and small-town people, equally fearful of the advent of a world war. One traveling salesman in Minnesota wrote, “For 20 years when asked what I thot of anything you have done, my reply has always been, ‘The King can do no wrong, you are my King.’ ”51

In 1914 and 1915 Dakotans were not just conflicted about the war; they were conflicted about which side they preferred. Germans and ethnic Germans from Russia and Hungary together represented more than a third of the foreign-born population in the Dakotas; largely rural communities still boasted German-language churches, newspapers, and school curriculum. Not surprisingly some of these immigrants sided with Germany early on or hoped for America to stay neutral, still a legitimate geopolitical strategy at the time.52 Others, however, had fled their countries because of their militaristic and imperialistic political cultures and supported the Allies, believing that the horrors of the war were inevitable in a society built on its glorification. Even the editors of the staunchly conservative and probusiness Fargo Forum expressed ambivalence about choosing a side in the first few months of 1914.53 As late as February of 1917, after Germans had renewed unrestricted submarine warfare, the editors maintained a somewhat open mind toward local pacifists, contending that the term “un-American did not apply to them.”54

But once the US had entered the war in April of 1917, Dakotans found attempts at “common sense and moderation” a difficult line to walk. Both states’ small but influential socialist organizations echoed the anti-war rhetoric of their European counterparts who saw the war as pitting one group of capitalists and imperialists against another in pursuit of wealth, with the poor and working classes sacrificing their lives. In Bowman, North Dakota, Kate Richards O’Hare said that men who volunteered for the military were seeking to become “fertilizer” and their mothers “were no better than brood sows.”55 Local pacifists also doubled down on meetings and public lectures—although they increasingly found that both private and public facilities were closed to them.56

The Nonpartisan League (NPL), the fastest growing radical agrarian organization on the Northern Plains in the 1910s, made what historian Michael Lansing has called a “nuanced” argument about the war—though, unsurprisingly, few of their conservative opponents thought it so.57 Like Populists Pettigrew and Lee a generation earlier, the leaders of the NPL believed that war was the tool of corporations, banks, and the elite to increase their wealth and power. Governor Lynn Frazier said simply that “North Dakota is not in favor of war”—indicating that war itself, as opposed to this particular war, troubled his constituents.58 NPL founder A. C. Townley told a crowd that in wartime the US was “working, not to beat the enemy, but to make more multi-millionaires.” He added that “in the heat and haste and confusion of war, they multiply their millions many times at your expense.” The LaMoure, North Dakota, editor described American soldiers as being “farmed by the capitalist class.”59 In Iowa a speaker borrowed from a speech given by Georgia Populist Tom Watson, “On the pretext of sending armies to Europe, to crush militarism there, we first enthrone it here.”60

But the radicals of the North Plains tried time and again to demonstrate that, even if they had been against the war—all war—they would not be disloyal to the American cause. Townley described this approach in 1917: “This nation of farmers are so patriotic that even though the government today may be in the hands and the absolute control of the steel trust, and the sugar trust, and the machine trust … we are going to do our best by producing all we can.”61 In fact Dakota farmers bought more than their share of war bonds and sent more than their share of soldiers to the front. Unlike some white men in the American South, the vast majority of Dakotans did not evade or refuse the draft.62

But few of the League’s opponents desired to understand the subtleties of the NPL’s position on the war. Instead big-business opponents of the League strategically attacked it for disloyalty to impede their economic reforms. Even George Creel, the leader of Wilson’s Committee on Public Information, and no fan of the NPL, noted that opponents seemed to be doing his work for him, by attacking leaders for disloyalty.63 Radical leaders were singled out throughout the region. Former South Dakota Populist senator and anti-imperialist Pettigrew was arrested after telling a reporter “there is no excuse for this war. We should back right out of it. We never should have gone into a war [while] the Schwabs make forty million dollars per year.”64 A. C. Townley and his manager were arrested for suggesting that wealth as well as men should be conscripted. Throughout the region NPL meetings were shut down by mobs, their leaders run out of town, in some cases tarred and feathered by mobs that knew they would face no retribution. In Bonesteel, South Dakota, two NPL organizers were captured and given to the sheriff, who in turn handed them over to a mob. In a rural area southwest of Mitchell, South Dakota, NPL organizer Emil Sudan was stripped naked, tarred and feathered, and dragged behind a wagon for miles.65

More complex were the attacks on Germans and German Americans on the Northern Plains, many of whom had recently joined the NPL due to its anti-war position. Beginning in 1917, and with the implicit permission of the federal government’s Committee on Public Information (CPI), “patriotic” Americans across the United States sought out Germans and other immigrants from nations of the Central Powers and violently enforced their loyalty. States with large populations of Germans, like North and South Dakota, passed laws against teaching or speaking German, or possessing German-language books. As we have seen, small colonies of religious sects, such as the Hutterites in South Dakota, faced particularly intense discrimination.66

But the cruelty of mobs knew no religious test. German Lutherans, German Catholics, and even some Scandinavians dubbed “German-Swedish” faced attack. In Wentworth, South Dakota, local officials outlawed an NPL meeting because so many Germans were planning to attend. The local newspaper reported that the participants used “the German tongue exclusively in their homes, in their religious services, and insist[ed] on being educated in German and speak[ing] a broken English.”67 The council of defense in South Dakota, although significantly less active and violent than their counterparts in neighboring Nebraska and Minnesota, nonetheless simultaneously subpoenaed thirty-five people to investigate their loyalty. A German farmer and his wife fainted when the sheriff arrested them.68

Through the efforts of “Wild Bill” Langer, North Dakota prevented some of the worst of these kinds of attacks. As historian Charles Barber has shown, Langer, then attorney general, could speak German himself and regularly sent and received letters in German. He also took steps whenever possible to protect Germans from discrimination. When the county superintendent closed a few schools in Cass County because they taught summer catechism in German, Langer immediately intervened, explaining that “the Constitution of the United States provides that religious liberty cannot be interfered with and that children who cannot speak English have a right to know God even though they are taught in German.”69 When he learned that Reverend Denninghoff, a registered “alien enemy of the government,” was teaching and administering a school under the auspices of the German Evangelical Church, he wrote him that “it would be advisable for you to discontinue this school immediately.” But he added, “This is not an order or anything of that sort, but is just a suggestion and I will be glad to have you come down to Bismarck at any time and talk this over with you.”70

Recent historians have contended that the wartime attacks on the NPL, its members, and the German community only served to help it recruit more members.71 In the short run, that may well have been true. And yet, when state and local governments violently attacked League organizers and threw them out of town if not into jail, they adopted a strategy that would become all too familiar and all too effective in the postwar period. Americans concluded that radicalism of any kind, and particularly the kind that looked to reform capitalism while at the same time bringing an end to war, was the antithesis of patriotic Americanism.

* * *

As they had in the Spanish-American War, Dakota men and women who served in the First World War saw firsthand both the undemocratic nature of military life and the inevitable horrors of war. At first glance, North Dakota farm boy David Nelson seemed an unlikely anti-militarist. From a relatively affluent family whose members almost certainly did not belong to the NPL, Nelson went to Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, and then to Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar. He arrived in the fateful fall of 1914 and almost immediately chose to work for Herbert Hoover’s Commission for the Relief of Belgium. For months, he wrote his mother, a German American, that reports of German aggression and atrocities were simply propaganda. But after a visit to occupied regions of northern France, his views changed radically and he began to see the true danger of a militaristic culture. He wrote, “militarism was in command … and militarism had hypnotized the people.” To Nelson, no less than the Hofer boys who had refused even to put on a military uniform, war imperiled the very nature of humankind. “[War is] humanity gone mad…. How then believe in human kind? How reconcile [war] with any living creed or faith? These little crosses, this line ‘mort pour la patrie’ … this weeping mother, wife, or child—no do not tell me … that all this sacrifice signifies nothing, that I could stand indifferent by.”72

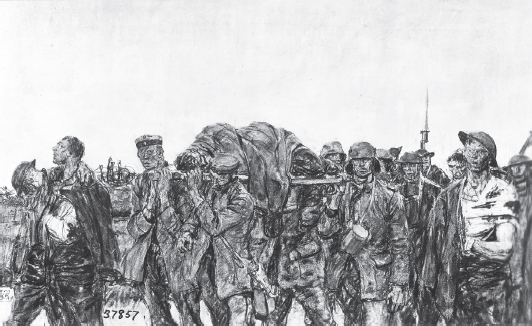

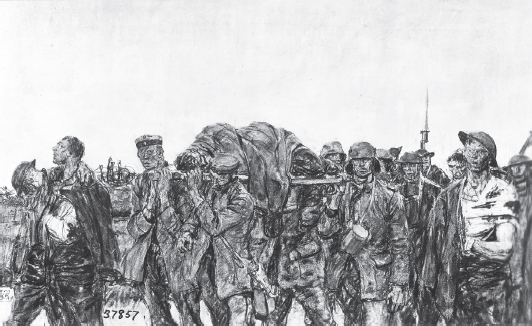

The artist Harvey Dunn saw what Nelson saw but he used a different medium to describe it. Long before he painted sentimental, yet inspiring, images of “pioneers” on the Northern Plains—evocative of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books—Dunn served as a combat artist; in that context his images were not heroic or romantic in the slightest. In fact, they could not “have been further from the kind of art” his employer—the War Department—had hoped he would create.73 Dunn had grown up on a South Dakota farm in the same county made famous by Laura Ingalls Wilder, but he sought every opportunity to follow his passion for art, eventually paying his own way through the Art Institute of Chicago and then volunteering for the American Expeditionary Force. His orders were to act much like a journalist, drawing what he saw, showing “war as it really is” but getting nowhere near actual combat.74 Somehow Dunn moved up to the front lines anyway and, while initially thrilled by the courage of the soldiers and the righteousness of the Allied cause, he soon became overwhelmed by the carnage and needless suffering on both sides. His charcoal sketches reveal a universal anti-militarism, an opposition to war itself—but also a refusal, in Nelson’s words, “to stand indifferent by.”

Many of Dunn’s anti-war paintings and drawings show the cost of war on individual men, what he called “the shock and loss and bitterness and blood” of it.75 The Sentry (1918), for example, shows a gaunt, haunted young man who surrounds himself with weapons, as if for luck. But Dunn’s most important and expressive anti-militarist painting shows the cost of war to a large group of men, to the community of humanity, without regard for nation or uniform. Prisoners and Wounded (1918) shows both injured Allied soldiers and captured German men. But the two opposing “sides” are rendered indistinguishable in the one-dimensional rain-soaked background and the monochromatic foreground of khaki uniforms, wet blankets, and blurred faces with corpse-like gaping mouths. The men are also fully anonymous, random arms and torsos blending into one another until the line of men is more like a blob. In this way the painting takes on an even darker tone than the better-known John Singer Sargent masterpiece Gassed (1919), in which each living man in the line remains a distinct human being. As David Lubin suggests, Dunn’s work resembles more closely John Stuart Curry’s 1938 painting Parade to War, An Allegory in which the legs, arms, feet of soldiers headed to war blur all together but their faces—actually, skulls—are distinct. Like Dunn, Curry was from a small town on the Great Plains—the heart of Populist resistance to war.76 As it happened, he was Dunn’s student too.

FIGURE 4. Harvey Dunn, Prisoners and Wounded, October 1918. Watercolor, charcoal, and pastel on paper. Dunn was a sketch artist for the army but often got closer to combat than he was commanded, so that he could show the reality of the war. Courtesy National Archives.

* * *

When the war ended most Dakotans, like many others all over the world, hoped it would be “the war to end all wars.” Only such an epochal outcome would justify the unspeakable suffering and loss. With that aim in mind, they created monuments in dozens of small towns, most of which did not glorify the war as much as encapsulate its horrors. The War Mothers Memorial (1924) in Bismarck-Mandan, North Dakota, like the celebrated Kathe Kollwitz sculpture The Grieving Parents (1932), primarily associates the war with loss; the cause is secondary; the idea of glory in war missing entirely. The town chose granite because boulders that had “withstood the storms and stress of the ages … best typif[ied] a mother’s love.”77 Its inscription reads, “In Memory of Our Sons and Daughters who lost their lives in the world war so that liberty might live.” A similar monument in the tiny town of Steele, North Dakota, reads simply “Our Boys.”78

But Dakotans also created a living appeal to peace, one which for a time became known around the world: the International Peace Garden. Eastern activists in the peace movement initially imagined planting a garden on the American-Canadian border to demonstrate how a world with peaceful boundaries—or no boundaries—might flourish. North Dakotans quickly suggested a location near the Turtle Mountains, thirty miles from the geographic center of North America. At that spot, they had already formed an “international peace picnic organization” and families from both countries were accustomed to meeting, eating, and playing sports together. As members of the memorial committee wrote, the four thousand miles of border between the US and Canada stretches “free from soldier, fort, and cannon” unlike almost any other in the world.79 More concretely, once the garden was in place, with fifteen hundred acres on each side, the border itself would be “wiped out.” The garden would become a place without a country “inculcating” peace around the world. Fifty thousand people gathered for the opening ceremony to which both President Herbert Hoover and Canadian prime minister William Lyon sent congratulations.

In the first decade of the garden’s formal existence, people around the world embraced the idea of a borderless world, even as threats to their own borders grew. In 1938 Glasgow, Scotland, hosted the Empire Exposition where an estimated eight million people viewed a replica of the International Peace Gardens. At a second opening ceremony in 1935 a member of the Canadian parliament commented, “If they had a string of peace gardens in Europe, do you think we should have a Mussolini moving into Ethiopia?”80 However overly optimistic, even naïve, such statements were, they reinforced the commitment to peace and, more enduringly, to anti-militarism among people on the Northern Plains—in both the US and Canada. None could see at that moment that far from being triumphant, the movement against war was in its last stages of power and influence. North Dakota would remain “the Peace Garden State,” even after nuclear weapons poisoned the soil beneath it.

* * *

There is no way to know how many Dakotans saw the anti-pacifist film Sergeant York in the weeks before Pearl Harbor, nor how many of the young men in the audience went directly from the cinema to the recruiting station, as filmmakers claimed. But we can know without a shred of doubt that the people of the Dakotas, along with other rural people in the Midwest, were its intended audience. Unlike the anti-war and anti-imperialist organizations in the 1890s and 1910s that brought together Americans from many different regions, the Populist anti-militarist movements of the 1930s centered in the broad middle of the country, perhaps even the Dakotas. Historians in our time blame the length of the war and its terrible cost in lives—including Jewish and Soviet lives—on America’s delayed entry, even calling anti-interventionists “Hitler’s American friends,” and taking little time to understand their views more completely.81 Populist anti-militarists did not come to their views quickly; nor were they attributable to their alleged ignorance of foreign affairs or the antisemitic beliefs they shared with many other Americans. While misguided in the context of Hitler’s imperial and genocidal ambitions, they carried forward a tradition steeped in fifty years of resistance to militarization, fear of concentrated power, and experience in combat.82 These were amplified by their simultaneous struggle against the increased power of the central government in the Great Depression.83 John Simpson of the Farmers Union had worried that agricultural programs might usher in an “army of workers” from the government to oversee their businesses. He surely knew that was but a glimpse of the kind of army workers might be forced to join if the US went to war once again.

In the 1930s leaders of the isolationist movement made familiar attacks on the idea of going to war—and many of the leaders were familiar too: Populist, Progressive, and NPL figures from the rural Midwest. In North Dakota Governor Langer was joined by the entire North Dakota delegation to Congress—William Lemke, Lynn Frazier, Usher Burdick, and Gerald Nye—to argue that war was nothing but murder, a means to line the pockets of eastern bankers and capitalist elites while young men went to their graves. They believed that the nation’s experience in World War I proved their point. With broad support in the region, in 1934 Senator Nye led a “special committee to investigate the munitions industry.” For two years the “Nye Commission” collected evidence that munitions manufacturers, Wall Street investors, and other “profiteers” had manipulated Wilson into declaring war in 1917. While they never found the conspiracy they sought, their well-publicized efforts were persuasive nonetheless. According to a 1937 Gallup Poll, 70 percent of Americans had revised their initial feelings of pride at their victory and believed instead that the US’s entry into World War I had been a dreadful error.84 The well-known Kansas publisher William Allen White warned “the next war will see the same hurrah and the same bowwow of the big dogs to get the little dogs to go out and follow the blood scent and get their entrails tangled in the barbed wire.”85 Reflecting these broadly held views, and revealing the degree to which many believed that simply not taking a side remained a viable option, Congress passed—and revised—neutrality laws in 1935, 1936, and 1937. As Elwyn Robinson wrote, by 1939 “what the country editors of North Dakota had written in their weeklies from 1914 to 1917 was the law of the land.”86

North Dakotans may have led the way, but South Dakota’s entire congressional delegation also adamantly resisted the idea of going to war or creating international alliances. Furthermore, they made sure the president and other interventionists understood that they were expressing their constituents’ views. Senator Francis Case, for example, read into the official record of the Senate a resolution by the American Legion of South Dakota—a newly minted veterans organization—at its annual meeting in Pierre: “Resolved, that it is the sense of this assembled conference of the American Legion, Department of South Dakota, that as to the European situation, the foreign policy of these United States be: To mind its own business, become involved in no entangling alliances, and let Europe settle its own problems without our interference or intervention.”87 Case’s counterpart, Senator William Bulow, used frontier imagery to argue against the Lend-Lease Act. He suggested that many South Dakotans would like to hang Hitler like a horse thief from a “sour apple tree.” But “before [we] would get our hands on Hitler to hang him, we would sacrifice several million of our own good American boys, who are worth more to us than all of Europe.”88 In the week after Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” address in early 1941, South Dakota congressman Chad Gurney read anti-war editorials from the Yankton Press into the official record of the House. The editor of the Press found Roosevelt’s words stirring, but he also wondered why Roosevelt thought it was the duty of the United States to bring democratic ideals to the world—“something we failed miserably to do some twenty years ago.”89

Populist anti-militarists from the region also fell back on antisemitism to make their points against the war. In sadly familiar terms, Nye and others warned against the international banking conspiracy, the influence of Jews on world affairs, and the impact of Jewish producers in Hollywood.90 He joined many others in Congress to vote against allowing Jewish refugees from Europe to settle in the US. Together with William Lemke and Karl Mundt of South Dakota, Nye joined Minnesota’s aviator-hero Charles Lindbergh’s America First Committee and spoke on its behalf, including to packed houses at Madison Square Garden, Chicago’s Soldiers Field, and the Rose Bowl. Lindbergh, of course, denied that he was antisemitic, while openly discussing the threat to peace that Jews represented and warning white Christians throughout the world to band together.91 Privately he was even less oblique, writing several passages openly hostile toward Jews, including, “We feel that … it is essential to avoid anything approaching a pogrom; and that … it is just as essential to combat the pressure the Jews are bringing on this country to enter the war. This Jewish influence is subtle, dangerous, and very difficult to expose…. they invariably cause trouble.”92 After a particularly virulent speech in Des Moines that drew national outrage, Nye doubled down on his commitment to the cause. Coming to “Lucky Lindy’s” defense, Nye blamed the interventionists for inserting a discussion of religion into the debate about war; he repeated that he himself was not antisemitic.93 He was far from alone: 90 percent of the thousands of letters to Lindbergh after the Des Moines speech supported and even extended his antisemitic views. The Petersons from Minneapolis explained, for example, “[Jews] did wrong in Germany and Germany got rid of them because of it.”94

Finally, Populist anti-militarists on the Northern Plains connected their experiences in the First World War with their struggles in the Great Depression, fearing that a new war could be yet another mechanism for the expansion of federal power. Populists were not anti-statists—far from it. Throughout the first fifty years of statehood, radical farmers had contended that the state could be put to beneficial, democratic, and anti-plutocratic use. But it had to be done under structures of local leadership and control. The New Deal was only acceptable, if at all, because many programs, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) in particular, were administered through county boards. But farm supporters and their conservative opponents alike resented the way New Deal programs empowered a distant federal bureaucracy. As the 1930s wore on, even some farmers who benefited from Roosevelt’s programs withdrew their support for the New Deal. They worried too about the increased power of a president who ran and won an unprecedented third term, asking if Roosevelt had not brought European-style totalitarianism to America’s shores.95

As the crisis in Europe grew, Dakotans suspected that Roosevelt and his planners were increasingly blurring the lines between domestic planning and military preparedness. They were not wrong. Historian Ronald Schaffer has shown that many New Deal programs flowed seamlessly from the governmental structures that had been designed for the “wartime emergency” of 1917. The requirements of the National Recovery Administration, for example, borrowed heavily from the price supports and regulatory structures of the War Industries Board; FDR even staffed it with WIB veterans. The Civilian Conservation Corps, what FDR called “Our Forest Army,” was set up so much like an actual army—with its tents, rations, platoons, and uniforms—that many Americans complained that they actually were wartime preparedness facilities. In some cases they actually were.96 Even the Agricultural Adjustment Act was merely the inverse in its purpose—to decrease production—to the wartime commodities programs’ purpose—to increase production.97 Montana senator Burton Wheeler saw a direct connection between the coercive statism of the First World War, the New Deal, and a new military imperative. In a direct reference to the AAA’s requirement in spring of 1933 that farmers “plow under” their crops, he declared that Roosevelt’s “triple-A foreign policy” would “plow under every fourth American boy.”98

Populist anti-militarists on the Northern Plains were also concerned that overlaps between peacetime and wartime bureaucratic structures would create a permanent increase in executive power. When FDR ordered Atlantic patrols to enter war zones and to “shoot on sight,” Charles Lindbergh accused him of conducting “government by subterfuge.”99 Nye saw the power of the wartime state at work in places where men and women would never expect: the movie theater. In short, Populist anti-militarists perceived a possible synergy between the increased authority of the federal government and growth of the military state to influence all parts of American life. For many reasons, Populist anti-militarists on the Northern Plains were wrong about delaying intervention in the war. Some of their reasons for doing so likewise were unjustifiable and the consequences are an inexorable part of our world today. But about their fear that such a war would usher in a permanent national security state and empower an imperial presidency, they were correct.

What they couldn’t have imagined was that, by the time it did, few Americans would see anything wrong with it.

* * *

Pearl Harbor came as a shock to all Americans, none more than the leaders of Populist anti-militarism who, like Lemke, had believed that “there is no nation or combination of nations that are a threat to the United States.”100 Nye and Lindbergh continued to believe that Roosevelt had known about Pearl Harbor in advance or perhaps had even played a role in planning it. They had little company. The vast majority of ordinary Dakotans quickly silenced their remaining doubts, accepted the legitimacy of the war and the wartime government, and rallied to the American and Allied cause. They followed the example of Senator Karl Mundt and shredded—either literally or figuratively—any evidence that they had been involved in anti-militarist activities. Then, also like Mundt, they would do everything they could to support the Allied war effort. In the end families on the Northern Plains would sacrifice men and money in larger amounts proportionately than Americans in most other regions.

The entry of American forces into the war silenced most—though not all—talk of the United States as a “fortress” nation that should stay separate from the world. In 1963, Robert Wilkins wrote that the occasional “isolationist” argument from Langer, Case, or Burdick—regarding the Marshall Plan, the United Nations, or the war in Korea—had sounded like echoes from “a living fossil.” In some corners these old Populist anti-militarists “drew snickers rather than applause.”101 Likewise, in Michael Kazin’s words, the term “isolationism” itself “became a synonym for anyone blind to the dangers of well-armed evils from abroad.”102 To Brooke Blower, it became “a cautionary tale for the post–Pearl Harbor future, not an accurate depiction of the past.”103 A new generation of leaders in the Dakotas, men like Republicans Mundt of South Dakota and Milton Young of North Dakota, learned quickly that “loyal” Americans embraced the mission of an interventionist military and, in the context of the Cold War battle against communism, rejected radicalism of all kinds. Rather than fearing a permanent standing army, Dakotans soon dedicated themselves to creating a place for it in their communities. When they did, they broke the bond between Populist agrarianism and Populist anti-militarism. Except for a highly controversial restoration during the Vietnam War and a far more muted one during the Farm Crisis, the proud Populist tradition would go forward unhinged from what had been its most distinctive element.