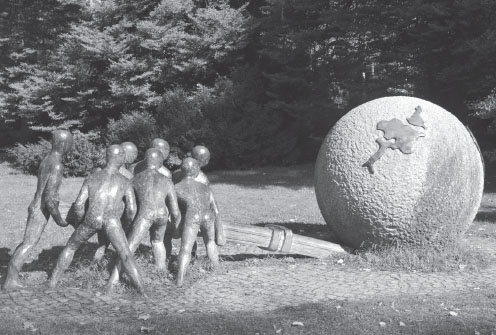

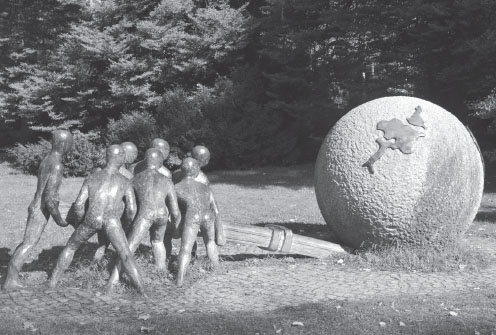

Children can move the Earth. PHOTO BEN KERCKX (PIXABAY).

The Global Peace Index—produced annually by the Institute for Economics and Peace—measures the state of peace in 162 countries according to 23 indicators that gauge the absence or the presence of violence. The 2016 Index (http://economicsandpeace.org) described a world that was less peaceful in 2015 than it was in 2008—a world increasingly divided between countries enjoying unprecedented levels of peace and prosperity while others spiraled further into violence and conflict. Eighty-one countries had become more peaceful, while seventy-nine had experienced conflicts. Europe, the world’s most peaceful region, reached historically high levels of peace with fifteen of the twenty most peaceful countries (including Iceland, Denmark, and Austria). At the same time, increased civil unrest and terrorist activity rendered the Middle East and North Africa the world’s least peaceful. (U.S. armed forces were active in the five least-peaceful countries—Syria, South Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia.) The intensity of internal armed conflict increased dramatically. The economic impact of violence in 2015 reached $13.6 trillion—13.3 percent of global GDP, equal to the combined economies of Canada, France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

The Index found that in countries with higher levels of “positive peace”—i.e., with attitudes, structures, and institutions that underpin peaceful societies—internal resistance movements were less likely to become violent and were more likely to successfully achieve concessions from the state.

The following list highlights some of the global initiatives designed to lead the world toward the goal of “positive peace.”

Numerous treaties have been created to protect portions of the global environment—the Kyoto Protocol, the International Framework Convention on Climate Change, the United Nations Law of the Sea, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora—but the series of major laws governing war and humanitarianism, the Geneva Conventions, fall short of protecting the natural world from the flames of war. Dr. Klaus Toepfer (former executive secretary of the United Nations Environment Programme) was among the first to call for a Green Geneva Convention, arguing that environmental security must be a fundamental part of any enduring peace policy and that those who deliberately put the environment at risk in war should face trial and imprisonment.

In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to incorporate the “rights of nature” in their constitution. Rather than treating nature as property, Ecuador believes that Pachamama (the Indigenous word for “Mother Earth”) has a legal “right to exist.” When environmental injuries occur, the ecosystem itself can be named as a defendant. Ecuador’s “Green Constitution” contains the following protections:

Article 1. Nature or Pachamama, where life is reproduced and exists, has the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions, and its processes in evolution…. The State will … promote respect towards all the elements that form an ecosystem.

Article 2. Nature has the right to an integral restoration.

Article 3. The State will apply precaution and restriction measures in all the activities that can lead to the extinction of species, the destruction of the ecosystems, or the permanent alteration of the natural cycles.

www.rightsofmotherearth.com/ecuador-rights-nature

On September 14, 2005, then representative Dennis J. Kucinich introduced H.R. 3760, a bill to create a cabinet-level Department of Peace and Nonviolence to promote nonviolent conflict resolution as an organizing principle to help create conditions for a more peaceful world. The Department would advise the president on matters of national security, including the protection of human rights and the prevention and de-escalation of unarmed and armed international conflict.

The mission of the Belgium-based Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP) is to promote, develop, and implement unarmed civilian peacekeeping as a tool for reducing violence and protecting civilians in situations of violent conflict. NP peacekeeping teams—currently deployed in the Philippines, South Sudan, Myanmar, and the Middle East—include experienced peacekeepers, veterans of conflict zones, and trained volunteers. NP’s Vision Statement reads, in part:

Our activities have ranged from entering active conflict zones to remove civilians in the crossfire to providing opposing factions a safe space to negotiate. Other activities include serving as a communication link between warring factions, securing safe temporary housing for civilians displaced by war, providing violence prevention measures during elections, and negotiating the return of kidnapped family members.

Nicaragua has an Autonomy Law that recognizes Indigenous sovereignty and an Ecological Battalion in its army that serves to protect the Bosawas Rainforest, a UN-designated World Nature Preserve. The forest was under siege by colonizers, farmers, cattle-ranchers, loggers, and miners until the deployment of 580 “eco-soldiers” in 2012. The mission, Operation Green Gold, is Central America’s first initiative to use soldiers to combat climate change by protecting Indigenous lands, wilderness, and native habitat. The armed eco-force has successfully reduced deforestation and illegal logging. Today 14 percent of Nicaragua’s undeveloped land is under armed protection.

The Worldwatch Institute has called for the Pentagon to provide “all documentation pertaining to the environmental conditions of U.S. bases” at home and abroad and commit to long-term, post-closure cleanup agreements. This would include comprehensive environmental assessments, conducted in collaboration with democratically appointed representatives from host nations. Worldwatch also calls for contaminated nuclear sites and test ranges to be permanently sealed off as enduring reminders of the folly of nuclear proliferation.

Plowshares policies would call for the diversion of tax dollars from weapons production to environmental restoration. If such policies were adopted, weapons labs would be required to cease military production and concentrate on mitigating the environmental damage caused by military activities. California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), a major designer of nuclear weapons, devotes just 2 percent of its budget to environmental restoration. In 1983, nearby residents formed Tri-Valley CAREs, a citizen’s watchdog group. Tri-Valley CAREs monitors radioactive pollution released by the LLNL while campaigning to transform the site from a weapons plant to a research center that addresses real-world solutions to energy, food, and health problems.

In 2012, in response to growing pressure from peace and human rights activists, the U.S. State Department established an Atrocities Prevention Board. In 2015, the State Department declared: “Preventing mass atrocities is a core national security interest and moral responsibility of the U.S.” The State Department now oversees a Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, a Complex Crisis Fund, and other “non-militarized strategies” that can be used in lieu of the armed escalations that still dominate U.S. foreign policy. As the Friends Committee on National Legislation notes, “Investing early to prevent war is far more cost-effective than military intervention after a crisis erupts.” Proactive peacebuilding efforts have proven successful in Kenya, Burundi, Sri Lanka, and Guinea, but continued funding for these programs remains uncertain.

With the bulk of the U.S. budget supporting costly military programs (while cuts are made in food stamps, social security, housing, and education), it’s time to consider a question posed by UNESCO: “What does the world want and how can we pay for it using military expenditures?” In 1978, UNESCO calculated that redirecting 30 percent of the world’s military expenditures ($780 billion) could solve most of the planet’s persistent problems, including: eliminating starvation; providing health care; offering shelter to the homeless; guaranteeing clean safe water; eliminating illiteracy; providing clean, safe, renewable energy; retiring all developing nation debts; stabilizing population growth; stopping erosion; halting deforestation; preventing ozone loss and acid rain; addressing climate change; removing land mines; providing refugee relief; eliminating nuclear weapons; and building democracy.

www.unesco.org; www.worldgame.org

In 2015, the International Institute for Strategic Studies reported the Pentagon’s $581 billion budget accounted for more than one-third of all military spending on Earth. For every $1 billion spent on the military, twice as many jobs could be created in the civilian sector. Investing in infrastructure—roads and bridges, schools, hospitals, clean water, and renewable energy—is wiser than pouring the money into single-use items like bullets and bombs. One billion federal dollars invested in the military creates 11,200 jobs: the same investment in clean energy could yield 16,800 jobs. The Borgen Project estimates that ending world hunger would cost $30 billion per year—the same amount the Pentagon burns through in eight days.

The Global Campaign on Military Spending is calling for the transfer of military money to fund five broad areas critical to a global transformation toward a culture of peace: disarmament and conflict prevention; sustainable development and anti-poverty programs; climate stabilization and biodiversity loss; public services/social justice, human rights, gender equality, and green job–creation; and humanitarian programs for the disadvantaged.

Since 1999, Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) has repeatedly introduced a Nuclear Disarmament and Economic Conversion Act (NDECA) requiring the United States to “dismantle its nuclear weapons” and redirect the savings “to address human and infrastructure needs such as housing, health care, education, agriculture, and the environment.” The NDECA would require the United States to “undertake vigorous, good-faith efforts to eliminate war, armed conflict, and all military operations.” Norton’s campaign has won the support of Physicians for Social Responsibility and the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (winner of the 1998 Noble Peace Prize).

Despite many calls for nuclear disarmament, the United States has done little to reduce or rein in the nuclear threat. There are treaties banning biological and chemical weapons, but there are no treaties banning nuclear weapons. Nuclear arms control agreements have reduced the world’s atomic arsenal from 56,000 to 16,300, but the White House (under both Obama and Trump) has called for spending $1 trillion on a new generation of atomic weapons and delivery systems. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) is working toward multilateral negotiations for a treaty banning nuclear weapons by engaging with humanitarian, environmental, human rights, peace, and development organizations in more than ninety countries.

The Humanitarian Pledge was issued on December 9, 2014, at the conclusion of the Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons, attended by 158 nations. This important document provides governments with the opportunity to move beyond fact-based discussions on the effects of nuclear weapons and into the start of treaty negotiations. As of February 2017, 127 nations had endorsed the Pledge.

In 1987, thanks to the influence of Dr. Helen Caldicott, the first president of Physicians for Social Responsibility, New Zealand’s Labour government passed a Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Act—thereby making New Zealand the world’s first nuclear-free nation. On February 28, 2000, Mongolia became the world’s second self-declared nuclear-weapon-free nation. There are five treaties establishing nuclear-weapons-free zones (NWFZ): the Treaty of Tlatelolco (Latin America and the Caribbean); the Treaty of Rarotonga (South Pacific): the Treaty of Bangkok (Southeast Asia); the Treaty of Pelindaba (Africa); and the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia. These NFWZs now cover 57 million square miles—56 percent of the planet’s land area. There also is a Treaty on the Prohibition of the Emplacement of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction on the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor.

The concept of recognizing special conflict-free sanctuaries goes back to the ancient Egyptians, Polynesians, and Hebrews and remains prevalent today. In 1987, the United Nations designated a vast stretch of the South Atlantic—reaching from the coast of Africa to the shores of South America—a “Zone of Peace.” In January 2014, thirty-three Latin American and Caribbean nations met in Cuba to renounce the use of war and proclaim a regional Zone of Peace. In December 2014, India called for designating the Indian Ocean a Zone of Peace. And there is an ongoing campaign to declare the Middle East a nuclear-free zone.

www.uia.org/s/or/en/1100016029

The $70 billion-per-year trade in weapons contributes to the escalation of violence and terrorism. The global arms trade aids dictatorships, creates international instability, and perpetuates the belief that peace can be achieved by arms. The world’s main arms exporters are the United States, Russia, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Arms manufacturers enjoy federal subsidies and lucrative government contracts, and they are free to sell weapons on the open market—sometimes arming both sides of a conflict or even “enemy” forces (as when the U.S.-armed Mujahedeen evolved into al-Qaeda, and U.S. arms for Iraq ended up in the hands of ISIS). As part of the UN mandate to protect “international peace and security,” the Campaign Against Arms Trade and other peace groups are calling on UN Security Council to add the arms trade to the International Criminal Court’s list of “crimes against humanity.”

www.caat.org.uk; www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/arms-control

In 1999, a commission of Nobel Peace Prize winners led by former Costa Rican president Óscar Arias drafted legislation to control global arms sales. The Arms Code of Conduct requires that countries wishing to buy arms must first meet certain criteria—including a respect for democracy and human rights. The code, which bans sales to dictatorships and oppressive regimes, poses a dilemma for America’s “military-industrial complex.” According to Demilitarization for Democracy [www.dfd.net], the Clinton Administration exported $8.3 billion in arms to fifty-two “non-democratic regimes”—including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Egypt, Thailand, and Pakistan—while providing military training to forty-seven dictatorships. The Obama Administration provided billions of dollars of weapons to oppressive regimes in Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates. Members of the European Parliament have challenged the United States to abide by an Arms Trade Code of Conduct adopted by the European Union.

The planet’s first peace park, the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, was established in 1932 to mark the friendship between the United States and Canada. There are now 143 peace parks in 42 countries. The United Nations and the International Union on the Conservation of Nature require that peace parks promote nonviolence and biodiversity in areas that have experienced “significant conflict.” After a 1995 border war between Peru and Ecuador in the Cordillera del Condor (a mountainous region rich in biodiversity), environmentalists and indigenous groups brokered a peace treaty that created parks on both sides of the disputed border and set the stage for a shared binational park that has served to ensure a lasting peace. Today, eighteen peace parks straddle countries with shared borders. Large transboundary peace parks link Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. Other parks share the borders of Albania/Kosovo/Montenegro, China/Pakistan, Costa Rica/Panama, and Mexico/United States. West Africa’s “W” International Peace Park has helped to reduce wildlife poaching and deforestation in the Niger River Basin. The Selous-Niassa Elephant Corridor protects critical wildlife areas between Tanzania and Mozambique.

Over the last 150 years, revolutionary new methods of nonviolent conflict management have been developed to end warfare. The Alternative Global Security System would replace the failed weapons-based national security approach with a concept of “common security” based on three broad strategies: (1) demilitarizing security, (2) managing conflicts without violence, and (3) creating a culture of peace. World Beyond War’s 2015 book, A Global Security System: An Alternative to War, describes the “hardware” of creating a peace system and the “software” (values and concepts) needed to operate and expand the system globally. The program includes detailed strategies to demilitarize countries, manage conflicts peacefully, reduce poverty, and promote environmental stewardship.

http://worldbeyondwar.org/alternative/

In Why Civil Resistance Works (2011), Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan demonstrated that over a span from 1900 to 2006, nonviolent resistance was twice as successful as armed resistance in creating stable democracies, with less chance those states revert to violence. History offers numerous examples of unpopular governments removed through nonviolent struggle—from Mahatma Gandhi’s campaign against the British to the overthrow of the Marcos regime in the Philippines and the rise of the Arab Spring. In 2015, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, a coalition made up of a labor union, a trade confederation, a human rights league, and a lawyers group that used nonviolence to establish a “peaceful political process at a time when the country was on the brink of civil war.”

The Pentagon’s global footprint of foreign bases, naval fleets, missile installations, and military interventions feeds hostility abroad. “Defense spending” primarily directed at “projecting U.S. military power worldwide” is not defensive. A first step toward demilitarizing national security would be to establish a “non-provocative defense” limited to defending national borders. A defensive military posture would eliminate long-range bombers, nuclear submarines, carrier fleets, and intercontinental missiles. Twenty-two countries have disbanded their militaries. Costa Rican president José Figueres Ferrer abolished the military in 1948 and invested heavily in cultural preservation, environmental protection, and public education. Costa Rica now boasts one of the highest literacy rates in the Americas.

www.peacesystems.org; peacemagazine.org

The United States has between 700 and 1,180 bases in more than 60 countries around the world. Eliminating foreign military bases—a goal of the Alternative Global Security System—goes hand in hand with nonprovocative defense. More than seventy years after World War II, the United States continues to maintain twenty-one military bases in Germany and twenty-three bases in Japan—bases that are a frequent source of resentment among local residents. Withdrawing from the military occupation of foreign countries would save billions and reduce the War System’s ability to inflame global insecurity.

www.tni.org/en/publication/foreign-military-bases-and-the-global-campaign-to-close-them;

U.S. drones are regularly used for targeted killings in Pakistan, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Somalia. The justification for these attacks (which have killed hundreds of innocent civilians) is the questionable doctrine of “anticipatory defense.” The White House claims the authority to order the death of anyone deemed a terrorist threat—even if the United States has not declared war on the countries attacked; even if the targets are U.S. citizens. Targeted killings violate the Constitution’s guarantee of due process. Ultimately, drones are counterproductive. As Gen. Stanley McChrystal (former commander of U.S. and NATO Forces in Afghanistan) has observed: “For every innocent person you kill, you create ten new enemies.”

www.stopdrones.com; http://nodronesnetwork.blogspot.com

The occupation of one country by another is a fundamental threat to security and peace that can provoke resentment and local resistance, ranging from street protests to armed resistance and “terrorist” assaults. The resulting conflicts often kill more civilians than insurgents while creating floods of refugees. The UN Charter outlaws invasion (unless they are in retaliation for a prior invasion—an inadequate provision). The presence of troops of one country inside another—with or without an invitation—destabilizes global security and makes armed conflicts more likely. Invasions and occupations would be prohibited under an Alternative Global Security System.

www.un.org/en/charter-united-nations/index.html

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization is a Cold War relic. The Warsaw Pact was disbanded following the collapse of the Soviet Union, but NATO (in violation of Western promises) has continued to expand and now encroaches on Russia’s borders. NATO has undertaken military exercises well beyond Europe’s borders—in Eastern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. An Alternative Global Security System would replace NATO with new international institutions designed to manage conflict without violence.

http://worldbeyondwar.org/outline-alternative-security-system

Social injustice, high youth unemployment, and economic desperation can create a seedbed for extremists. The imbalance between the affluence of the Global North and the poverty of the Global South could be righted by democratizing international economic institutions and taking care to conserve the ecosystems upon which all economies rest. Competition for limited resources stokes tensions between nations and within nations. Using natural resources more efficiently and developing non-polluting technologies can reduce ecological stress. As the former UN under secretary general for Disarmament Affairs Jayantha Dhanapala has said: “Wars claimed more than 5 million lives in the 1990s, and nearly 3 billion people, almost half the world’s population, live on a daily income of less than $2 a day. Poverty and conflict are not unrelated; they often reinforce each other…. Even where there is no active conflict, military spending absorbs resources that could be used to attack poverty.”

www.un.org/disarmament/education/activities.html

A Global Marshall Plan (GMP) designed to achieve economic and environmental justice worldwide could democratize international economic institutions. The goal would be similar to the UN Millennium Development Goals: to end poverty and hunger, develop local food security, provide education and health care, and achieve stable, efficient, sustainable economic development. To prevent the GMP from becoming a policy tool of rich nations, the work could be administered by an independent, international nongovernmental organization. The GMP would require strict accounting and transparency from recipient governments.

The United Nations’ failures to solve the planetary threats facing humankind are due to its very nature. The United Nations has no legislative powers—it cannot enact binding laws. It has failed to solve the problems of social and economic development, and global poverty remains acute. It has not stopped deforestation, climate change, fossil fuel use, global soil erosion, or ocean pollution. Instead of promoting disarmament, the United Nations requires members to maintain armed forces that can be called upon for “peacekeeping” missions. The World Court has no power to bring disputes before it. The General Assembly can only “study and recommend” and lacks the power to change anything. The United Nations must either evolve or be replaced, perhaps by a nonmilitary Earth Federation composed of a democratically elected World Parliament with power to pass binding legislation.

www.earthfederation.info; http://worldparliament-gov.org

In 1999, the United Nations General Assembly approved a Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace. Article I called for: “Respect for life, ending of violence and promotion and practice of non-violence through education, dialogue and cooperation; … [c]ommitment to peaceful settlement of conflicts.” The UN General Assembly has identified eight action areas: fostering a culture of peace through education: promoting sustainable economic and social development; promoting respect for all human rights; ensuring equality between women and men; fostering democratic participation; advancing understanding, tolerance, and solidarity; supporting participatory communication and the free flow of information and knowledge; and promoting international peace and security. The Global Movement for the Culture of Peace, founded by UNESCO in 1992, is a partnership of civil society groups working to make militarism obsolete.

www.culture-of-peace.info/copoj/

The prowar bias commonly seen in schoolroom history texts also infects mainstream journalism where many reporters, columnists, and news pundits promote the fable that war is inevitable and that it brings peace. “Peace journalism” (conceived by scholar Johan Galtung) encourages editors and writers to explore nonviolent alternatives to conflict. In contrast to war journalism’s “good guys versus bad guys” approach, peace journalism focuses on the structural and cultural causes of violence and explores peace initiatives commonly ignored by the mainstream media. Examples include the Center for Global Peace Journalism’s Peace Journalist magazine and the Oregon Peace Institute’s PeaceVoice.

www.park.edu/center-for-peace-journalism; http://blog.orpeace.us

Let them march all they want, as long as they continue to pay their taxes.

War-tax refusal has a long tradition among religious and secular opponents of war—including Quakers, Mennonites, and Brethren. Conscientious Americans have refused to pay taxes for virtually every U.S. war. (Henry David Thoreau was famously jailed for refusing to finance Washington’s war on Mexico.)

In 1984, the War Resisters League issued an Appeal to Conscience that read, in part:

It is clear that the U.S. government’s ability to threaten, coerce, and, if deemed necessary, make war on other nations is a direct result, not only of our economic might, but also the unprecedented size of our military arsenal, which is now far larger than that of all our allies and “enemies” combined. It is equally clear that the maintenance of this arsenal depends upon the willingness of the American people—through their federal tax payments—to finance it…. Refusal to pay taxes used to finance unjust wars, along with refusal by soldiers to fight in them, is a direct and potentially effective form of citizen noncooperation, and one that governments cannot ignore.

Homo sapiens constitute a single species, with a marvelous diversity of ethnic, religious, economic, and political systems. With climate-stressed global disasters already under way—including massive deforestation and unprecedented rates of extinction—we face a planetary emergency. We need to place the long-term health of the global commons above the short-term goals of national interest. Protecting the commons is best achieved by voluntary consensus and a recognition of mutual respect that arises out of a sense of responsibility for the planet’s well-being. Conflict does not have to lead to war. We have established nonviolent methods of conflict resolution that can provide for common security—a world free from fear, want, and persecution, and a civilization in balance with a healthy biosphere.