Food and Power in the New Deal, 1933–42

“The city-dweller or poet who regards the cow as a symbol of bucolic serenity,” declared U.S. Circuit Court judge Jerome Frank in 1941, “is indeed naïve.” Presiding over an acrimonious legal battle involving the price of milk, Frank noted that the liquid gently coaxed from a cow’s udder might be “indispensable to human health,” but it was also responsible for “provoking as much human strife and nastiness as strong alcoholic beverages.” Frank had witnessed such nastiness firsthand as a member of the “Brains Trust” in Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal administration. As legal counsel for the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), Frank spent much of his time shaping federal milk policies, attempting to hammer out compromises among dairy farmers, milk bottlers, deliverymen organized in labor unions, and urban consumers. Earning himself a reputation as a “brilliant wild man” and a “potent left-winger” for his work on behalf of small black and white farmers, Frank worked to craft agricultural policies that would also benefit urban workers and consumers, even if those benefits came at the expense of large farmers and food processors. Frank’s prolabor and proconsumer efforts at the AAA put him at odds with the first administrator of the agency, George N. Peek, who pegged Frank as an intellectual city-boy and tried unsuccessfully to have him fired. Peek’s successor, Chester C. Davis, likewise saw Frank’s politics as counter to the USDA’s core constituency of commercial farmers, and in February of 1935 “purged” Frank and dozens of his like-minded colleagues from the AAA. Milk politics alone did not doom Frank’s career as an economic liberal within the Department of Agriculture, but his efforts to frame farm policy as an issue of concern to all Americans highlighted one of the central tensions within the New Deal.1

The bitter fights surrounding the price of milk during Frank’s brief tenure in the AAA represented a broader political struggle over farm and food policies during the early years of the New Deal. In response to the Great Depression, organized farmers, consumers, businessmen, and laborers all renounced laissez-faire ideology and demanded government intervention in the food economy. The New Deal policies erected in response to these conflicting demands engendered prolonged debates over the proper role of the state in regulating and administering the economy. Of particular concern was the decades-old dilemma of monopoly power in an age of mass produced and mass consumed food. Should the government break up monopolies such as the widely reviled “Milk Trust” or the “Big Four” meatpackers to protect the interests of small farmers and urban consumers? Or would action against these efficient businesses, which employed thousands of workers, actually do more harm than good in an economy reeling from underconsumption in the city and overproduction on the farm? The answers to these questions would dictate the future of New Deal economic liberalism, since government intervention in the food economy inherently affected every U.S. producer, consumer, and worker. Neither conservatives nor liberals could readily justify “free enterprise” in the farm economy at a time of worldwide economic crisis—yet neither could they agree on how the state could effectively intervene to benefit the greatest number of Americans.

From the beginning of Franklin Roosevelt’s term in office until the entry of the United States into World War II, antimonopoly and agrarian rhetoric clashed with the reality of farm policies that benefited large-scale farmers and powerful food processors at the expense of smaller farmers, urban workers, and consumers. Beset by conflicting demands from all of these groups, liberal New Dealers such as Jerome Frank and Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace struggled to balance the concerns of workers, consumers, and small farmers with the interests of corporate agriculture. Their efforts, though only partially successful, made government regulation of private farming and food processing enterprises a central but deeply controversial aspect of New Deal political economy. As later chapters show, the expansion of long-haul trucking transformed the nature of this political question, as powerful agribusinesses relied on unregulated trucking to develop “free market” solutions to the New Deal-era farm problem. To understand that transformation, however, we must first understand the roots of the farm problem and its implications for the political economy of the New Deal in an era of railroad-based transportation. Despite the economic liberalism that animated the New Deal in a time of depression, the material reality of a transportation infrastructure forged during the Gilded Age required significant compromises—particularly the acceptance of a certain degree of monopoly power within the farm and food economy.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION AND THE FARM PROBLEM

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 put farm prices and food costs front and center in U.S. politics, but the issue had deeper historical roots. The “farm problem” first became politically salient during the Populist movements of the 1880s and 1890s. Southern tenant farmers pressed by the credit squeeze of the crop lien system, along with northern plains farmers struggling to adjust to globalizing wheat markets, called for a strong federal government to countervail the power of the nation’s “money interests”—landlords, banks, and especially railroads. Although the Populists failed to elect their presidential candidates in the 1892 and 1896 elections, they successfully put the farm problem on the nation’s political agenda. Progressive reformers of the early twentieth century adapted many of the Populists’ ideas as new legislation and policies, from the strengthening of the Interstate Commerce Commission to the establishment of rural producers’ cooperatives to improve the leverage of farmers in agricultural markets. These policy efforts had some success in mitigating the farm problem, but even more important was the rising global demand for U.S. farm products that drove up prices in the 1910s. The period leading up to and through World War I witnessed a “golden age of agriculture” that significantly defused political agitation by farmers.2

The farm problem returned to the nation’s political consciousness with a vengeance in the 1920s. Huge surpluses created by production for World War I led to a postwar drop in farm prices and an agricultural depression. Congressmen from rural states in the South and West reacted by forming a “farm bloc” devoted to increasing farmer’s incomes, either by limiting agricultural production, by dumping surpluses on foreign markets, or by guaranteeing farmers a “parity” price for their crops. Attempts to pass legislation such as the McNary-Haugen Bill foundered in the 1920s, however, as farm representatives from different regions of the country could not reach consensus on the proper mechanism for assuring steady farm incomes. But when the Great Depression struck in 1929, desperate farmers called urgently upon the federal government for relief. Herbert Hoover’s Farm Board attempted to implement the least statist proposals of the McNary-Haugen era—particularly voluntary marketing associations to shore up farm prices—but with little success. Most farmers, as individual business owners, refused to cooperatively reduce their production to increase prices. The agricultural depression continued. As farm prices and credit structures collapsed, sending even formerly prosperous U.S. farmers deeply into debt, laissez-faire ideology lost its hold in the countryside, paving the way for heavy government intervention in the depressed rural economy.3

One of the Roosevelt administration’s first acts was to sign into law the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933. The legislation sought to shore up farmers’ incomes through both price supports and production controls, making centralized economic planning the cornerstone of New Deal farm policy. Price supports were meant to guarantee stability in the agricultural marketplace, with the visible hand of government creating what Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace called an “ever-normal granary” through federal purchases of surplus crops. Production controls, meanwhile, would force farmers to reduce the amount of acreage planted to crops through an unprecedented extension of government power. These policies—which combined government subsidization with planned scarcity—helped raise farm incomes for many commercial farmers, but at the cost of forcing thousands of small farmers, tenants, and sharecroppers off the land. Even as the AAA sought to limit farmers’ production, the scientific bureaus of the USDA continued to push farmers to use pesticides, fertilizers, hybrid crops, and tractors to boost yields. Encouraged by economists such as M. L. Wilson, who helped formulate the AAA production control policies, the USDA’s technological and scientific efforts from the late nineteenth century into the 1930s focused on creating giant industrial farms where commodities could be produced factory-style. New Deal farm policies reaped rewards for the Democratic Party by securing solid political support from large commercial farmers, but also pushed many small, “inefficient” farmers out of the market. The AAA consequently offended conservatives as an affront to free enterprise while liberals decried the programs for harming the most vulnerable members of rural society. As we shall see, this tension between large and small farmers, and between conservatives and liberals, would shape farm policy debates for several decades after the economic crisis of the Great Depression.4

The farm problem, however, was not just a problem for farmers. The price of milk, meat, bread, and produce impacted every U.S. family trying to put food on the table during a devastating depression. The AAA’s focus on taming overproduction put farm policies at odds with other New Deal economic reforms, since raising farm prices increased the cost of food for urban industrial laborers and consumers, who were also members of the emerging Democratic coalition. Even as agricultural policymakers formulated plans for slashing production of midwestern wheat crops in the spring of 1933, unemployed factory workers queued up in breadlines in the nation’s largest cities. In the summer of 1933 bakers began charging eight to ten cents for loaves of bread that had previously cost five cents. Consumers around the country blamed farm policies for inflating the price of bread and flooded the offices of President Roosevelt and Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace with letters demanding change. In the fall of 1933 and spring of 1934, the farm program came under heated attacks when Wallace ordered six million hogs culled and one-quarter of the southern cotton crop plowed under to increase market prices. Critics of the New Deal ridiculed the Roosevelt administration for destroying food and fiber when millions of Americans were starving and poorly clothed. The federal government appeared to be subsidizing powerful farmers and rural landlords at city dwellers’ expense.5

In an effort to stave off a full-scale revolt against New Deal farm policy, Wallace appointed veteran trustbuster Frederic C. Howe to the office of AAA Consumers’ Counsel in June 1933. An ally of Jerome Frank, Rexford Tugwell, and other urban liberals in the AAA who hoped to transform the entire agricultural economy rather than merely raise farm prices, Howe gained the authority to investigate consumer complaints against food processors, distributors, and retailers. Although Howe’s actions had no direct impact on New Deal farm policies, his office energized a growing consumer movement. By publishing the Consumers’ Guide, a master list of food prices in the nation’s major cities, Howe hoped to “awaken public sentiment and put its power behind the drive to get more money for the farmer without gouging the consumer.” Howe worked assiduously to prevent profiteering in the food economy—so assiduously, in fact, that he was included in the “great purge” of liberals from the AAA in 1935. Although Secretary of Agriculture Wallace sympathized with and encouraged Howe’s antitrust harangues, AAA administrator George N. Peek believed that consumer purchasing power was outside the ambit of the farm program. As Peek put it, the AAA was part of the Department of Agriculture, not the “Department of Everything.”6

The split between agrarians and urban-industrial reformers within the Department of Agriculture in the early years of the New Deal was due in part to the divergent personal histories of the individual policymakers involved. Agrarian reformers—represented by farm leaders George N. Peek and Henry A. Wallace, economists M. L. Wilson and Howard R. Tolley, and sociologist Carl C. Taylor—were all born in the rural Midwest, had been educated at midwestern land-grant schools, and either began their early careers working as farm businessmen (Peek and Wallace) or as agricultural economists or rural sociologists in the USDA/land-grant college complex (Wilson, Tolley, Taylor). Wallace, for instance, was the grandson of Henry Wallace—the founder of the influential farm journal Wallace’s Farmer—and the son of Henry Cantwell Wallace, who served as secretary of agriculture under Presidents Harding and Coolidge. Before becoming Franklin Roosevelt’s first secretary of agriculture, Henry A. Wallace attended Iowa State College, wrote scientific articles and political editorials for Wallace’s Farmer, and in 1914 founded the hybrid seed corn company that later became Pioneer Hi-Bred. Wallace was no conservative—he firmly believed the federal government could and should intervene in the agricultural economy to nurture a Jeffersonian republic of landed farmers, and furthermore believed the government should play an active role in diffusing scientific knowledge to those farmers. Wallace’s politics were forged, however, in the rural Midwest, where white family farmers did not encounter the same racial tensions and extremes of poverty and wealth that plagued the farmscapes of the South and West and the industrial cores of the nation’s largest cities. The urban-industrial reformers who joined the New Deal Department of Agriculture, by contrast, formed their political consciousnesses in more cosmopolitan spheres far removed from heartland agriculture. Rexford G. Tugwell, Jerome Frank, and Frederic C. Howe were all born in the urbanized Northeast, attended prestigious private colleges, and spent their early careers practicing law or teaching in Ivy League universities. Jerome Frank, for instance, was born in New York City in 1889 to German-Jewish immigrants who later moved to Chicago. At the age of sixteen Frank entered the University of Chicago, where he studied political science before entering the Law School, from which he graduated with the highest grades in that school’s history. After spending several years on Wall Street practicing corporate law, Frank met Felix Frankfurter, an influential Harvard legal theorist who, like Frank, sympathized with the politically and economically disempowered members of U.S. society. Frankfurter, a personal friend of Franklin Roosevelt, encouraged Frank to join the Department of Agriculture in 1933 as Rexford Tugwell’s top legal aide. Frank took the job, and brought with him a host of like-minded cosmopolitan reformers, including a young Alger Hiss, Thurman Arnold, and Adlai Stevenson.7

Both the agrarians and the urban-industrial reformers denounced laissez-faire capitalism in the rural economy, but their political philosophies had little else in common. Agrarian reformers such as Wallace concentrated their concerns on the perceived plight of the white-owned, family-run, commercially oriented midwestern farm, which they understood to be the moral, political, and economic “backbone” of the nation. Antitrust actions against railroads and meatpackers and government stabilization of commercial farmers’ incomes formed the core of these agrarians’ political-economic philosophies. Urban-industrial reformers such as Tugwell and Frank, however, saw agricultural policymaking as part of a broader political package that could bring European-inspired progressive social reforms. Firmly planted in the intellectual Progressive political tradition of labor scholar John Commons, trustbuster Louis Brandeis, and legal realist Felix Frankfurter, the urban-industrial reformers within the AAA expected New Deal farm policy to help urban consumers lower their food costs, provide tools for African American and poor white landless farmers to rise up the “agricultural ladder” to land ownership, and foment European-style social democracy in labor organization as well as farm policy. For these urban-industrial reformers, the example of 1930s Swedish farm politics provided at least as much inspiration as the U.S. agrarian movements of the nineteenth century. In Sweden in 1933, the Social Democrats cemented a decades-long hold on political power by allying their core constituency of urban industrial laborers with farm interests in the Agrarian Party. Under the leadership of agrarian Per Edvin Sköld, the Social Democrats declared that Swedish farmers and workers suffered similar exploitation under capitalism and so had to unite as producers to attain mutually beneficial political power. The Swedish approach held little appeal, however, for U.S. agrarians such as George N. Peek, the first head of the AAA. Peek denounced Frank and his colleagues as a “plague of young lawyers” who had their “hair ablaze” with radical ideas about “collectivist agriculture”—ideas that animated the early New Deal but also ensured the intellectual city boys would have short careers within the tradition-bound USDA.8

The divisive nature of New Deal farm policies also reflected broader conflicts within rural U.S. society and politics in the 1930s. In the American South, cotton and tobacco production dominated a landscape in which landless farmers struggled to climb out of persistent indebtedness under the crop lien system established in the wake of the Civil War. Groups such as the Communist-led Share Croppers’ Union (formed in Alabama in 1931) and the Socialistled Southern Tenant Farmers Union (formed in 1934) sought to unite black and white tenant farmers in a mass revolt against racial and economic oppression in the cotton belt. Southern tenant and sharecropper farmers understood that the AAA’s production controls and price supports were unlikely to benefit them. They were soon proven correct. Planter elites took the vast majority of government price-support payments for themselves, while using the AAA’s acreage-reduction provisions to evict tenants from the land. Despite organizing a massive 1935 cotton-pickers’ strike, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union collapsed in 1939. The group faced not only terroristic reprisals from white southern elites but also internal divisions, as the group’s Socialist leaders sought collectivist agriculture while rank-and-file members wanted private land ownership. Radical organizations such as the STFU, furthermore, may have gained some sympathy from left-leaning agricultural policymakers such as Gardner Jackson within the AAA, but tenants’ pleas for land redistribution held little sway in Congress, even before the 1935 “purge” in which Jackson was included.9

With southern Democrats in the driver’s seat of the congressional farm bloc, commercially oriented farm organizations did not need mass strikes to gain the ear of farm policy legislators. The most powerful farm organization, the American Farm Bureau Federation, was formally founded as a national group in 1919. The Farm Bureau united local and state farm educational institutions that had been founded during the Country Life Movement of the early twentieth century, when agricultural reformers such as Cornell horticulturalist Liberty Hyde Bailey aimed to enlighten supposedly benighted U.S. farmers in the science of farm productivity and farm management. With the 1914 passage of the Smith-Lever Act, nearly every county in the nation would soon have a federally funded county agent serving under the Federal Extension Service. These county extension agents, tasked with propagating the technical knowledge forged in the nation’s land-grant agricultural colleges, formed tight relationships with local farm bureau agents—relationships so tight that critics would decry the “Farm Bureau-Extension Axis” for making the county agent a “tool for politicians.” By the 1930s the Farm Bureau was the nation’s largest farm organization by far, maintaining an active lobbying presence in Washington and an “umbilical attachment” to farm policymakers at every level of governance. The Farm Bureau exerted more pressure than any other group on New Deal farm policy, but its power was diluted somewhat by internal divisions. As a national organization, the Farm Bureau tried to simultaneously represent southern cotton planters, northern grain growers, and western cattle raisers—farmers whose views on issues such as tariffs, production controls, and price supports were often in direct opposition. A host of other farm organizations, furthermore, added to the cacophony of voices heard in the halls of Congress. The National Farmers Union, founded in 1902, took root primarily among northern plains grain farmers in the 1910s by promoting European-style cooperatives dedicated to strengthening farmers’ access to credit and markets. Although commercially oriented and ill-disposed toward organizing mass revolts of black or white landless farmers, the Farmers Union claimed to represent the interests of small family farmers. Throughout the twentieth century the Farmers Union would criticize the Farm Bureau’s leaders as big businessmen intent upon using farm policy and federally funded science and technology to drive common farmers off the land.10

The tensions within 1930s farm politics revealed more than a clash of personalities in the AAA and differences among interest group lobbyists, however. Debates over interventionist farm programs revealed contradictions inherent to the political economy of the New Deal. Conservative critics of the New Deal predictably decried the farm program as a decisive step toward state socialism, even though congressional conservatives from southern and western states had written the enabling legislation of the AAA in consultation with the conservative American Farm Bureau Federation. For many Democrats though, the far more troubling concern was not right-wing attacks but the farm program’s potential to split apart the emerging New Deal coalition. While both liberal and conservative farm policymakers framed the agricultural depression as a result of overproduction, urban labor and consumer advocates pointed instead to the need to boost consumer purchasing power. Even labor- and consumer-friendly agricultural policymakers could not agree on how best to reconcile policies aimed at raising farmer’s incomes with urban Americans’ demands for affordable foodstuffs. Some liberal New Dealers, including Frederic Howe and Henry A. Wallace, advocated antitrust action against meatpackers to restore competition to the food economy. Others, such as Jerome Frank, called instead for the government to cooperate with monopolistic meatpackers and milk distributors to achieve efficiencies in the mass production and mass distribution of food. The only thing all could agree upon was that the federal government could and should play an active role in managing the farm economy.

These conflicts over the “problem of monopoly” were not confined to farm politics. Concerns over corporate power led to acute disputes over every major aspect of New Deal economic reform, from labor policy to antitrust action to regional planning initiatives. In labor policy, for instance, the 1933 passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) provided workers with an unprecedented state-guaranteed right to organize their own unions under section 7(a), while simultaneously providing business leaders with the tools to create legal cartels under “codes of fair competition.” The National Recovery Administration (NRA) quickly proved a dismal failure in stabilizing U.S. business, even before the Supreme Court declared the NIRA unconstitutional in 1935. Section 7(a) nonetheless provided impetus to the labor movement’s efforts to tie collective bargaining to economic recovery. New Deal labor advocates such as William Leiserson declared that a “living wage” for U.S. workers would raise consumer buying power, overcoming the problem of “underconsumption” that economists such as Paul H. Douglas, business leaders such as Edward A. Filene, and liberal politicians such as Robert F. Wagner (D-NY) understood as the underlying cause of the Great Depression. “Purchasing power” became a rallying cry after 1933 for workers who looked to the federal government to provide economic security. In 1935 Congress passed the Wagner Act, guaranteeing workers the right to organize their own unions and collectively bargain with employers. Recalcitrant corporate leaders refused to acknowledge a new era of labor empowerment, however, so workers had to wage their own fights for industrial democracy, and often relied on radical Communists to lead the battles. After a successful 1937 sit-down strike by militant General Motors employees, millions of inspired employees joined new industry-wide unions, many under the umbrella of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which promoted racial harmony as essential for mass unionism’s success. Millions more joined the older, craft-based American Federation of Labor (AFL), where racial and gender exclusion based on white male workers’ assumption of superiority hammered cracks in the façade of working-class cohesion. By the end of the 1930s, New Dealism had inspired a massive upswing in organized labor’s power on the shop floor and in the political sphere. New Dealism also cemented the resolve of liberals within the Democratic Party to boost purchasing power, even if that required redistribution of business profits into workers’ pockets.11

The laissez-faire approach to labor relations was officially dead after 1935, as New Deal economic liberals announced that capitalism could not survive without government intervention to assure a modicum of social justice and economic fairness. Deep, unresolved tensions remained within the New Deal labor universe, however. Corporate executives, conservative labor leaders, and southern Democrats in Congress remained hostile to the perceived radicalism of the militant CIO. White male workers in both the AFL and the CIO struggled to maintain their assumed prerogatives of masculinity and whiteness, while millions of southern and western workers of all races and genders remained unorganized. And although the politics of “purchasing power” could serve to boost labor’s claims to primacy within the New Deal coalition, it also held the potential to generate a political backlash among middle-class consumers and small business owners whose economic interests seemed threatened by state-backed labor power. All of these conflicts were built into the New Deal order from the outset, and as we shall see, would dog the ideas and practices of economic liberalism through the mid-twentieth century.12

New Deal economic liberalism also had contradictory roots and implications in the arena of government-business relations. The “problem of monopoly” took center stage in the early years of the New Deal. Trustbusters both inside and outside the federal government—including Roosevelt advisor Thomas G. “the Cork” Corcoran, Harvard law professor Felix Frankfurter, and Democratic Senator Joseph O’Mahoney of Wyoming—drew on Populist and Progressive-era rhetoric to call for curbs on corporate power. Economist Gardiner Means’s concept of “administered prices” resonated with this crowd, who sensed that modern corporations set prices according to their firms’ needs rather than in the public interest. Yet the exigencies of business bankruptcies in 1933 led the Roosevelt administration to downplay the problem of monopoly in its first effort to revive the industrial economy. The NRA, seeking to revive “business confidence,” allowed businesses to self-regulate their prices and wages through cartels that were exempt from antitrust laws. Business self-regulation failed to end the Depression, however, as the NRA “codes of fair competition,” even when businesses chose to comply with them, did little to stimulate production or boost consumption. By the time the Supreme Court killed the NRA with its 1935 Schechter Poultry v. United States decision, most New Dealers agreed that self-regulation was not a viable path to economic recovery. Meanwhile populist figures such as Senator Huey P. Long (D-LA) and Detroit “radio priest” Father Charles Coughlin attacked the New Deal for failing to rein in corporate power, pushing President Roosevelt to reconsider antimonopoly policies. After denouncing “economic royalists” for transforming private enterprise into “privileged enterprise” in his 1936 acceptance speech for renomination on the Democratic presidential ticket, Roosevelt cultivated closer ties to trustbusting New Deal advisors. One of the principal drafters of the “economic royalists” speech, Thomas Corcoran, became Roosevelt’s right-hand-man on economic affairs. Corcoran’s friend, Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes, delivered a blistering radio speech in December 1937 warning of the threat of a “big-business Fascist America—an enslaved America.” In 1938, Thurman Arnold, as the new head of the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, stepped up enforcement of existing antitrust laws; by 1940 Arnold had initiated 93 prosecutions and 215 investigations of economic concentration. Senator Joseph O’Mahoney, as chair of the Temporary National Economic Committee, carried out sweeping investigations of monopolistic practices in dozens of important industries from 1938 to 1941. The antimonopoly fervor of the late 1930s would fade, however, as the nation entered World War II, when the need to mobilize an “arsenal of democracy” made the bigness of big business a national asset rather than a liability.13

Despite shifting antimonopoly politics, however, by the end of the 1930s New Dealers had fundamentally transformed the government’s power to regulate and administer the nation’s economy in the name of “the public interest.” Besides strengthening the power of older agencies such as the Interstate Commerce Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Antitrust Division, New Dealers erected powerful new regulatory bodies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Communications Commission, and the Civil Aeronautics Authority. But if New Deal economic liberals forged a consensus regarding the need for government intervention in private enterprise, deep contradictions remained. Large corporations such as General Motors or Ford might have deserved censure for making private enterprise into “privileged enterprise,” but they also effectively used techniques of mass production to make consumer goods such as automobiles affordable to the nation’s masses. After the labor movement’s successes in the mid-1930s, furthermore, such giant corporations provided good wages and secure employment to millions of organized American workers. Federal antitrust action, meanwhile, was often more effective as a means of courting popular approval of the New Deal rather than actually serving “the public interest.” The chain-store food and clothing stores that dominated U.S. retailing in the 1930s, for instance, underwent constant antitrust investigations and anti-chain legislation through the decade, and yet probably did more to keep consumers’ expenses for necessities in check than any government agency during the Depression. Although the New Deal cemented the role of the federal government in regulating and administering the nation’s economy, contradictory ideologies and definitions of “the public interest” posed inherent challenges to economic liberalism even at its highest tide.14

Despite the contradictions, the New Deal brought unprecedented intervention in the agricultural economy, transformations in labor relations, and upended the nineteenth-century laissez-faire tradition of government-business relations. By setting the United States on a liberal political-economic course in response to the global crisis of capitalism of the 1920s and 1930s, New Dealers raised the stakes of ideological and political conflict over the proper relationship between a democratic federal government and capitalistic private enterprise. By delving further into the nature of the “farm problem” of the 1920s and 1930s, however, we can see that the battles waged among farmers, consumers, business leaders, and policymakers over the shape of New Deal economic liberalism were not simply the product of long-standing ideological divides or of predictable interest-group politics. The intractability of the farm problem in the 1930s was, in important ways, a product of the material structure of the farm and food economy—namely the centrality of the railroad in U.S. food distribution. In an era when most urbanites did not raise or process their own crops or livestock, transportation technology was an essential factor in determining the prices farmers received for their commodities, the wages workers earned in food industries, the profits to be had by food manufacturers and distributors, and ultimately the prices that consumers paid for foodstuffs. Transportation technology did not act as a force outside of human society to determine the shape of political and economic conflict, but the technological structure of a rail-bound nation established the framework within which such conflicts took place during the New Deal era. A close look at the milk and beef industries, both of which involved intense political struggles over monopoly power within the food economy of the 1930s, reveals the extent to which the politics of the farm problem—and by extension, labor, consumer, and business politics—were inextricable from the nation’s reliance on railroad technology.

THE “FAIR PRICE” OF MILK

In the early twentieth century, Progressive reformers convinced city dwellers that cow’s milk was necessary for human health. This was news to many urban consumers, who had for several decades considered cow’s milk to be a “babykiller,” produced by diseased animals fed on distillery wastes (or worse). The introduction of refrigerated rail transportation in the 1890s, however, along with pasteurization and sanitary glass bottles, helped dairy farmers and enterprising milk dealers transform the feared “baby-killer” into “nature’s perfect food” in the early twentieth century. Consumers who had previously shunned cow’s milk began to demand high-quality milk, delivered year-round, at prices that working families could afford. Milk dealers such as Borden and National Dairy Products offered to meet these needs by pasteurizing, bottling, and delivering milk to consumer doorsteps for a profit. To do so, however, bottlers had to make significant capital investments in processing and distribution technologies, and expected to capture market share proportionate to their investments. Dealers also had to pay premium prices to dairymen to enable farmers to invest in disease-free cattle herds, quality feed, and clean barns. Furthermore the extreme perishability of milk, especially in the days before most consumers owned refrigerators, required daily delivery services by milkmen—teamsters who, along with coal and ice wagon drivers, had developed craft unions that were among the most successful in the country in gaining wage concessions from employers. As long as consumers felt they were paying a fair price for a quality product, and as long as farmers, bottlers, and teamsters believed the profits to be gained were fairly divvied up, milk might not have caused animosity. But conflicting interpretations of what constituted a “fair price”—conflicts that were at their heart based on the geographical structure of dairying in an age of railroad transport—meant that milk production and marketing was one of the most deeply politicized economic concerns of the first half of the twentieth century.15

The cost of transporting this highly seasonal and highly perishable product structured much of the conflict within the milk economy of the early twentieth century. Transportation costs were first defined as the key factor in milk pricing by Johann Heinrich von Thünen in his 1826 essay The Isolated State. Von Thünen, a Prussian gentleman farmer seeking to understand what made some farms more profitable than others, imagined a city surrounded by perfectly flat and uniformly fertile farmland. What a farmer decided to raise at any particular location in this imaginary world, predicted von Thünen, would depend on two variables: the price city consumers were willing to pay for a particular food and the cost of transporting those foods to market. A farmer located close to a city would profit most by producing fruits, vegetables, and fresh milk, considering that consumers were willing to pay a premium for these highly perishable foods, thereby offsetting the high costs of daily transportation. Farther away from the city, where land rents were lower, a farmer could make better profits producing grains, meat, and manufactured dairy products like cheese and butter. Although they brought lower prices in the market, these less perishable commodities had sufficiently lower transportation costs to make up the difference.16

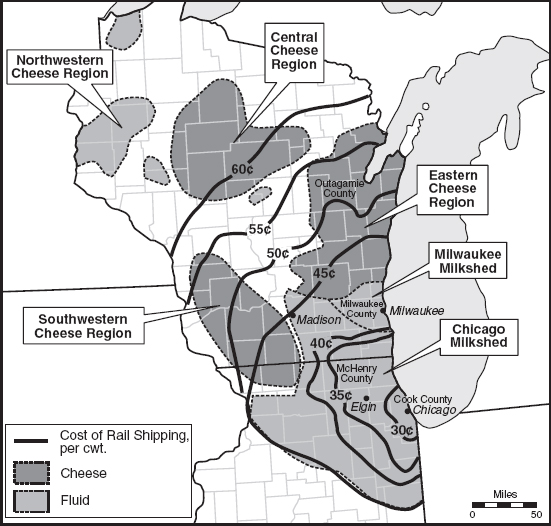

Von Thünen’s abstract model, which imagined farmers located in a series of concentric “rings” surrounding cities, has been criticized by geographers and historians as unrepresentative of a world in which cities are not isolated in the center of featureless plains. Nonetheless von Thünen’s theory was remarkably accurate in predicting the geographical outlines of city milksheds that developed in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was because railroad transportation was the only effective means of delivering fluid milk to the nation’s expanding cities. Railroad transportation costs were directly tied to a farmer’s distance from the city, enforcing compliance with von Thünen’s rings. The rates charged by railroads for delivering milk to cities increased with distance, making shipment of fluid milk from beyond approximately 100 miles prohibitively expensive for outer-ring farmers (see figure 1.1). As a general rule, dairy farmers close to major cities such as Chicago and New York City, who benefited from lower transportation costs, could invest capital in the equipment and quality herds necessary for sanitary milk. Farmers located farther from the city, however, faced high transportation charges that prevented them from culling tuberculosis-prone cattle from their herds—these farmers needed all the milk they could get. Farmers deeper in the dairy hinterlands of northern Wisconsin and upstate New York thus focused on producing lower-quality milk suitable only for butter and cheese manufacturers located in rural districts. Through the 1910s and 1920s, local and state officials cemented this geographical division by imposing strict railroad rate structures and public health codes that ensured that dairy farmers in the inner ring would produce tuberculosis-free milk for drinking, while outer-ring farmers would only produce milk for eating as cheese or butter.17

Cows, however, remained unwilling to cooperate with the rhythms or politics of industrial society. Before the widespread adoption of growth hormones that made the dairy cow amenable to industrial production in the latter half of the twentieth century, cows tended to produce far more milk during the spring than in other seasons. During spring, cows ate the juiciest grasses and produced great quantities of milk in expectation of feeding their calves. Milk dealers trying to supply consumers with year-round milk consequently had to pay farmers to overproduce in the spring in order to have a sufficient supply later in the year. This surplus milk could, of course, be turned into Euro-American society’s oldest convenience foods—cheese and butter—except that farmers who lived farther away from cities, and were consequently shut out of urban milk markets by transportation costs and health regulations, already produced milk for cheese and butter. These more distant dairy farmers did not need the expensive equipment, the spotless barns, and the tuberculosis-free cows required to meet the health standards that city officials demanded for fluid milk supplies. Nonetheless these distant farmers had to accept a lower price for their milk than city milk producers, and consequently suffered when the spring surpluses of city farmers flooded cheese markets and drove down prices. Dairymen located close to cities likewise resented more distant farmers who tried to evade public health regulators and sell lower-quality milk to city dwellers at cut-rate prices. Furthermore some farmers located somewhere between cheese and fluid milk dairymen tried to get the highest price possible for their milk by selling either to cheese factories or to city milk dealers, depending on the season. Milk dealers, for their part, relied on this market instability to force down the price they had to pay the rest of the year to inner-ring farmers. The cow’s refusal to produce evenly throughout the year, coupled with the inherent geographical tension between the fluid milk and the manufactured milk markets, led to constant power struggles among farmers—struggles that would shape the elaborate milk politics of the 1930s.18

Figure 1.1. Wisconsin and Northern Illinois Milksheds, 1932.

The cost of shipping milk by railroad established a radial geography of milk production. Fluid milk producers clustered close to metropolitan centers, while cheese and butter producers remained in the “outer rings” (Sources: Wisconsin Cartographers’ Guild, Wisconsin’s Past and Present: A Historical Atlas [Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998], 48; H. A. Ross, The Marketing of Milk in the Chicago Dairy District [Urbana: University of Illinois Agricultural Experiment Station, 1925], 470).

Events of the early 1930s transformed these related issues of seasonal surpluses and geographical tensions into a contentious issue of New Deal-era political economy—the so-called milk problem. Sustained droughts ravaged pastures in the Midwest and Northeast, reducing the average milk production per cow by 9 percent between 1929 and 1933. In order to regain their production levels, dairy farmers increased their herd sizes—primarily by choosing not to kill or sell off low-yielding cows. When pastures began to improve, farmers consequently faced unprecedented surpluses produced by extraordinarily populous dairy herds. Meanwhile consumers hit hard by the Depression spent less money on dairy products—especially cheese and butter, which lower-income Americans tended to cut back on during hard times, when they chose substitutes such as oleomargarine. Oversupply and slack demand drove down the prices farmers received for their milk by 51 percent between 1929 and 1933. Cheese and butter farmers saw their incomes drop rapidly, with the wholesale price for butterfat dropping by 58 percent in the same period. In early 1933, with the combination of low prices and large surpluses raising the stakes of competition in dairying, the longstanding division between inner-ring and outer-ring farmers predicted by Johann von Thünen set the stage for desperate action.19

Impoverished farmers began violently demanding higher prices for their milk in 1933, paving the way for massive government intervention in the nation’s milk markets. Farmers in New York, Illinois, Michigan, and elsewhere withheld their milk from market, often dramatically dumping it on the road, in efforts to drive up the price dealers paid for their milk. One of the first and most spirited milk strikes occurred in Wisconsin in February 1933, when a group of several thousand farmers organized the Wisconsin Cooperative Milk Pool. The leader of the Milk Pool was Walter M. Singler, a “firebrand” who traveled around the state wearing a red blazer, cowboy hat, goatee, and spats while whipping farmers’ rallies into a frenzy with tirades against the Milwaukee and Chicago “Milk Trusts.” Singler, in concert with Milo Reno of the Iowa-based Farmers Holiday Association, called upon farmers to withhold their products from market, forcing buyers to offer a “fair price plus profit.” On February 15, 1933, Singler told his followers that a statewide strike would be necessary to achieve this. Singler first proposed a five-day “peaceful strike,” but his lieutenant in the Milk Pool, A. H. Christman, recommended “literally knock[ing milk dealers] over the head with a club.” Within days, Milwaukee area farmers took up Christman’s call to arms, withholding their milk from market and “swarming over the roads of Outagamie County [north of Milwaukee], dumping truckload after truckload of milk and roughing up [truck] drivers.” Farmers blocked roads with heavy timbers, threatening milk factories with dynamite and diesel fuel in their storage vats. Sheriffs hastily deputized locals to escort milk trucks to town with shotguns and tear gas to prevent a “milk famine” in Milwaukee.20

The violence of the Milk Pool strike dramatized one of the key conflicts at the heart of the “milk problem”—the division between outer-ring cheese farmers and inner-ring fluid milk farmers. The inner-ring farmers who provided milk for the urban markets of Milwaukee and Chicago were already organized into two strong cooperative associations, the Milwaukee Cooperative Milk Producers and the Pure Milk Association, which maintained exclusive contracts with city milk dealers and thus held no animus toward companies like Borden or National Dairy Products—the members of the so-called Milk Trust. The inner-ring farmers who belonged to the Milwaukee Milk Producers and the Pure Milk Association tended to be larger, relatively prosperous farmers who “despised” farmers who were “[Milk] Pool-minded.” One such prosperous dairy farmer remembered in an oral history that members of the Milwaukee Milk Producers were “pretty well satisfied” with milk prices in the 1930s while Milk Pool members tended to be “the farmers that didn’t run a good operation.” In less subtle words, there was a recognized class division between well-off inner-ring milk farmers and poorer upstate cheese dairymen.21

The Milk Pool strike of 1933 set the stage for federal regulation of the nation’s milksheds. Organized dairy farmers and city milk dealers in Chicago sought an opportunity to prevent a recurrence of the strike by regulating upstate cheese farmers out of the city milk market. The Agricultural Adjustment Act provided the tools to do so. The day after President Roosevelt signed the act, representatives of the Pure Milk Association and their allies, the large milk dealers of Chicago, petitioned Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace to begin administering milk prices in the Chicago milkshed. Wallace responded by establishing a Dairy Section of the AAA, headed by economist Clyde L. King, and by calling a series of regional hearings to negotiate an agreement among the dairy farmers and milk distributors of the Chicago milkshed. From that agreement would emerge a system of milk marketing orders that, for the next thirty years, would invoke federal government power to uphold the milk monopoly of inner-ring dairy farmers and urban milk dealers. Although the railroad-based “Milk Trust” predated the New Deal, policies erected during the earliest days of the New Deal effectively cemented the power of this innerring milk coalition—at least until trucking technology upended the economic geography of milk distribution in the 1960s.22

The marketing orders that emerged in 1933 drove a federally administered regulatory wedge between outer-ring cheese dairymen and inner-ring fluid milk farmers. Government administrators, cooperating with milk dealers and organized inner-ring dairymen, would prevent future outbreaks like the Milk Pool strike by establishing a firm price difference between milk used to manufacture cheese or butter and milk sold to city consumers in bottles. The federal system stabilized milk prices by preventing farmers in either the outer or inner rings from dumping their seasonal surpluses on each others’ markets. Inner-ring farmers enjoyed protection from the intrusions of outer-ring farmers on their markets, and vice versa. Milk dealers agreed to cooperate in the milk marketing agreements even though it meant they would be forced to buy from inner-ring farmers at higher prices, because the system guaranteed them a reliable source of disease-free milk at government-stabilized prices. The first federal milk marketing agreement went into effect in Chicago in 1933, and although it quickly broke down due to lack of enforcement, it was copied in cities around the country including Boston, Indianapolis, Detroit, New York, and Philadelphia, and was soon reinstituted in Chicago. After Congress passed the 1937 Agricultural Marketing Act, bolstering the constitutionality and enforceability of the marketing orders, USDA administration of prices in the nation’s milksheds became a permanent policy for dealing with the “milk problem.”23

The marketing orders initiated by Chicago’s inner-ring dairy farmers and corporate milk dealers, however, ignored the interests of two very important groups—organized urban milk deliverymen and city consumers. The USDA’s single-minded focus on dividing farmers into abstract geographical rings did not address the wage demands of urban labor unions. This was no small matter, since Teamsters controlled the house-to-house distribution of milk in the presupermarket era. In the negotiations that established the Chicago order, the issue of Teamster wages had been thoroughly discussed. In particular, Jerome Frank, the general counsel for the AAA during the drafting of the orders, advocated adherence to section 7(a) of the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act to include workers’ demands for decent pay as an integral component of the marketing order system. Milk dealers in Chicago originally agreed to maintain high wages for organized deliverymen in that city—less out of sympathy for the labor movement than out of pragmatic fear of the powerful Teamsters locals in Chicago, who threatened to derail the negotiations. Over the previous two decades, Chicago’s Teamsters had proven willing to use anything from fists to dynamite to protect their economic interests; for milk dealers, paying decent wages to drivers was a matter of survival. Jerome Frank nonetheless rightly feared that if the Chicago marketing order did not include a written guarantee of the right of dairy employees to bargain collectively, milk deliverymen in other cities might suffer. Urban teamsters who had not developed the strength of the Chicago deliverymen might suffer wage cuts, Frank argued, if milk dealers used the pretense of the orders to pass onto labor the higher costs of their federally administered milk supplies. An urban liberal who viewed the AAA as a means of achieving a European-style social welfare state rather than as a mere tool for raising farmers’ incomes, Frank would be included in the famous “purge” of liberals from the USDA in 1935. Without Frank, the USDA would administer all of its future milk marketing orders with little effort to appease organized labor—an oversight that would remain unresolved until the 1960s, when milk dealers would rely on highway transportation to make the Teamsters obsolete in the milk economy.24

Consumers, like the Teamsters, called for government policies that benefited not only corporate food processors but also average Americans during the 1930s and 1940s. The federal milk marketing orders, consumers protested, were undisguised attempts by the Milk Trust to increase the retail price of milk and boost their own profits. Before the milk orders, chain grocery stores such as the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company and independent “cash-and-carry” stores began competing directly with milk dealers such as Borden and National Dairy Products. At a time when the cost of home delivery accounted for over a third of the price of a bottle of milk, while dealer profits took five cents and payments to farmers took forty cents of every consumer dollar spent on delivered milk, eliminating home delivery provided the simplest means for milk retailers to cut milk prices without harming profit structures or infuriating organized inner-ring dairymen. By not delivering directly to consumers’ doorsteps, Chicago’s chain stores and cash-and-carry outfits were able to sell a quart of milk for only nine cents in 1932—two cents less than the home-delivered price. Chicago’s milk dealers, having written the nation’s first milk marketing order on their own terms in 1933, sought government support to eliminate this competition by requiring all retailers to sell milk at the price of a home-delivered quart. In pushing for a minimum price for store-bought milk, dealers claimed that chain stores were able to sell their milk cheaply only by using it as a “loss leader” and by “sweating their labor.” Upon the advent of the milk marketing order, store milk prices rose from nine cents to eleven cents per quart. When the USDA called a hearing in Chicago in November of 1933 to assess the system’s strengths and weaknesses, consumer representatives lodged bitter complaints against this minimum retail price. The most succinct protest came from one Sylvia Schmidt, who saw price fixing as an unfair tax on consumers: “People who want the privilege of having their milk delivered should pay for that privilege and people who are willing to take the inconvenience of getting their milk [from a store] should be allowed the difference in price.” Chicago resident Rose Fourier agreed, noting that “consumers are quite angry” at being “compelled by the Government” to pay higher prices for milk from powerful dealers such as Borden. Robert S. Marx, representing the Kroger Grocery chain, pointed out that his company was “forced to charge the consumer for a [home] delivery service that we don’t give him, that he does not want, that he cannot afford to pay for.”25

Chicago consumers’ protests against the injustice of the minimum retail price convinced the USDA to eliminate the policy from future iterations of its milk marketing orders. However, the primary goal of the Dairy Section of the AAA was to stabilize farmers’ prices, and under the leadership of Clyde L. King, the USDA believed this could best be achieved by cooperating with the largest milk dealers. This meant that when milk dealers in cities throughout the country petitioned their city or state milk control boards to set minimum retail prices for milk, the USDA made no effort to stop the de facto reinstitution of price-fixing arrangements. In 1939, Fortune magazine surveyed 129 cities and found that half of them had retail price-fixing laws, forcing the average chain store to sell a quart of milk at four cents over cost, even though most chains believed one cent would be a reasonable margin. Consequently most consumers had little choice but to pay an extra three or four cents for the “convenience” of having their milk delivered to their doorsteps. The milk marketing order system, dedicated to boosting the incomes of organized inner-ring dairy farmers, made no room for lower-cost distribution methods, thus entrenching the economic power of monopolistic milk dealers—at least until supermarkets began using long-haul trucks to circumvent the power of milk dealers in the 1950s.26

The federal milk policies of the New Deal era did not effectively solve the milk problem, because the milk marketing orders did not take into account the interests of either workers or consumers. While organized inner-ring dairy farmers and urban milk dealers gained the support of USDA administrators, workers and consumers were forced to take the problem of a “fair price” for milk into their own hands. The late 1930s saw numerous strikes by organized Teamster milk delivery drivers in Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, New York, and Cleveland—all asking for, and gaining, a greater portion of the milk dollar. Milk dealers such as Borden remained dependent on the Teamsters to deliver milk from the processing plant to consumer doorsteps, and so generally responded to drivers’ wage demands by increasing the price of milk to consumers. With federal administrators encouraging dairy farmers, milk bottlers, and Teamsters to increase the price of milk, consumers cried foul. Given the New Deal’s focus on the problem of strengthening consumer “purchasing power” to overcome the Depression, consumers demanded federal investigations into the assumed price predations of the Milk Trust.27 Consumer outrage at the prices charged by national dairy chains like Borden and National Dairy Products culminated in 1939 with vitriolic antimonopoly hearings before the Senate’s Temporary National Economic Committee, chaired by Wyoming senator and inveterate trustbuster Joseph O’Mahoney. The following exchange between O’Mahoney and Frederic C. Howe, former Consumers’ Counsel of the AAA, captures the gist of the hearings, which resulted in antitrust actions against the national dairy distributors:

O’MAHONEY: Is it your conclusion, after all your studies, that distributors maintain the price of milk at an excessively high figure which is not warranted by the cost of production?

HOWE: It is.28

The USDA’s efforts to stabilize the dairy industry satisfied only a powerful minority of those affected by the price of milk—that is, organized inner-ring farmers and city milk dealers. Consumers, Teamsters, and outer-ring farmers shut out from the federal milk marketing orders all continued through the early 1940s to agitate for a “fair price” for milk. Despite massive government intervention in local milk economies, the milk problem remained fundamentally unsolved by New Deal policies.

In 1942 journalist Wesley McCune, a liberal sympathetic both to the demands of organized farmers and organized labor, sought to understand “Why Milk Costs So Much?” He found a ready answer: USDA milk marketing orders, having been hijacked by inner-ring dairy farmers and their corporate allies in the milk bottling industry, had resulted in “a plain conspiracy to raise prices.”29 But the milk marketing orders did not emerge primarily from nefarious collusions between agricultural policymakers and corporate milk dealers. Instead agricultural policymakers within the AAA Dairy Section intended the orders to realize and reify the geographical theories of Johann von Thünen—to use the power of the federal administrative state to enforce an economic division between outer-ring and inner-ring dairy farmers to stabilize farm incomes. Consumers and Teamsters had no reason to accept the federal milk marketing orders, however, since von Thünen’s model sought only to predict how to maximize farmers’ profits in relation to transportation costs. Within the theoretical space of von Thünen’s concentric rings, there was no room for real-world political and economic contests among consumers, workers, farmers, businessmen, and government officials. These endemic conflicts over the fair price of milk would continue to plague economic liberals seeking to resolve the milk problem through the end of World War II. As we shall see in later chapters, it was not until truckers began hauling most milk in refrigerated trucks that the milk problem would cease to animate consumer and worker attacks on regressive New Deal farm policies.

BEEF AND THE PROBLEM OF MONOPOLY

As in the case of milk, the cost of transporting beef from farmer to consumer played a fundamental role in the farm and food politics of the New Deal era. The refrigerated railcar, introduced in the 1870s, provided a means of sending relatively inexpensive dressed beef from the cattle-producing regions of the Midwest to the beef-consuming Northeast. However, the rapid perishability of fresh beef required a distribution system of unprecedented scale and technological integration that laid the foundations for what came to be known as the “Beef Trust.” From the 1870s until the 1950s, a handful of giant firms dominated every aspect of converting western cattle into eastern steaks and roasts, from buying and selling in stockyards to slaughtering the animals and distributing carcasses to retail butchers. During the height of New Deal economic liberalism, the “Big Four” meatpackers drew repeated attacks from farmers, consumers, small businessmen, and politicians who demanded an overthrow of monopoly power in the meat industry. But as in the milk industry, the structure of the railroad-based beef economy prevented New Dealers from satisfying the diverse demands of all interested parties. In contrast to milk, however, the federal government made little effort to intervene directly in the beef economy.

The rise of monopoly power in meatpacking was tied to the industry’s reliance on an extensive system of refrigerated railcars to distribute their product to the masses. Uncured beef begins to rot immediately after slaughter, so achieving a tasty steak in the nineteenth century required that a cow be kept alive until just before it was distributed to consumers. No form of transportation was speedy enough to allow a mid-nineteenth-century meatpacker to mass-slaughter western cattle and deliver the beef to eastern consumers in edible form at a reasonable price. Furthermore the cow is a long-legged beast with about 45 percent of its weight taken up by inedible hide, bones, gristle, entrails, horns, and hooves. Carrying such a low proportion of saleable meat, the bulky beef steer did not make for transport economics efficient enough to justify long-distance shipping, especially since cattle were apt to die or be injured in railroad cars and needed repeated watering and resting on a lengthy trip. As a consequence, the slaughter and distribution of beef in urban centers was a highly atomistic, small-scale industry carried on mainly by neighborhood butchers who slaughtered cattle only as needed. The development of the refrigerated railroad car made mass distribution possible for the first time in the 1880s and set the stage for the monopoly power that would define beefpacking until the 1950s. Gustavus Swift, the key figure in this technological revolution, was determined to find a way to ship dressed beef rather than the entire steer to eastern consumers, thereby eliminating the cost of transporting the inedible parts of the animal. Building on the work of earlier inventors and entrepreneurs, Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase, who perfected the refrigerated railcar in 1878, using an innovative combination of insulation and ventilation to provide cool, dry air that kept beef carcasses fresh between Chicago and New York. By 1884, Swift was the largest shipper of dressed beef in the country, though he soon faced competition from giant Chicago meatpackers George Hammond, Nelson Morris, and Philip Armour. With the deployment of the refrigerated railcar, beef slaughter began a geographical shift from the small butcher shops of the East to the enormous meatpacking factories of Chicago.30

Dressed beef was cheap for consumers, but came at the cost of economic concentration of the industry. The reduced costs of shipping dressed beef allowed the Chicago packers to sell meat profitably in New York at prices 5 to 10 percent lower than local slaughterers. The mass distribution of dressed beef was no simple task, however. Enormous capital investments in technology were essential if the dressed beef packers were to achieve the low prices needed to overcome resistance to the new product. Eastern consumers distrusted dressed beef from Chicago, delivered over a thousand miles by an unseen butcher and touched by an unknown number of railroad men. Only a very low price could trump the presumed risk of food poisoning. Eastern butchers, meanwhile, saw a direct threat to their livelihood, and generally refused to carry dressed beef in their meat markets. Railroads were also uncooperative. In their effort to increase traffic volume in the West during the 1860s and 1870s, railroads had made large investments in livestock cars and urban stockyards. Dressed beef would make this equipment obsolete while taking half of their western routes’ most lucrative cargo. Facing such resistance, the Chicago packers constructed their own infrastructure to bypass the wholesale butchers and railroads. Swift erected hundreds of “branch houses,” or cold storage stations, in eastern cities and towns. Branch houses received carloads of dressed beef, then immediately distributed the meat to local retailers before spoilage set in—all without the need for wholesale butchers. To circumvent the railroads that refused to provide refrigerated railcars, Swift and his competitors built their own. Swift also found an ally in the Canadian Grand Trunk Railroad, which unlike the New York Central or the Pennsylvania Railroad had no significant investments in the livestock business, to send its dressed beef to New York. With an enormous, tightly integrated technological system, the dressed beef packers achieved economies of scale that made inexpensive meat both a widely accepted food and a highly profitable line for the packers. In short, the introduction of the refrigerated railcar sowed the seeds of monopoly in beefpacking.31

From the beginnings of dressed beef in the 1880s to World War I, a handful of Chicago meatpackers sought to dominate the entire trade. These firms, led by Swift and Armour and known as the “Big Five”—and after 1923, the “Big Four”—used capital and technology to maintain a tight grip on the nation’s meat business.32 With their branch houses, the Big Five dominated the wholesale distribution of beef in both large and small cities located on railroad lines throughout the heavily populated areas of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. Independent meatpackers were almost entirely shut out from the branch house system. The Big Five also owned most of the railroad car routes connecting packing houses to distant branch houses—in 1918, the Big Five owned 90 percent of such routes, making it nearly impossible for smaller packers to market their product over a long distance. By maintaining this stranglehold on the infrastructure of distribution, the Big Five achieved control of 73 percent of the nation’s interstate meat trade by 1916. Significantly most of the profits gained by the big packers through their monopoly power were immediately reinvested in their distribution systems—building more branch houses and refrigerator cars—in order to gain economies of scale and increase their control over marketing. Dressed beef marketing was inherently big business.33

The capital investments required for nationwide mass distribution compelled the packers to slaughter unprecedented numbers of cattle to achieve economies of scale in mass production. With its giant Union Stock Yard, built in 1865, Chicago gained a reliable source of cattle from the grasslands of the West. To further assure reliable supplies, the Big Five invested in stockyards in other major cattle markets such as Kansas City, St. Louis, and Omaha. When the Federal Trade Commission investigated the Big Five’s monopoly power in 1917, officials discovered that the firms owned a majority of shares in twenty-two of the fifty largest stockyards, with more than eight of every ten cattle passing through yards in which the big packers held an interest. The Big Five located their slaughtering plants strategically in the railroad centers that connected the marketing channels of the populated East with the livestock production areas of the West. Their control of stockyards allowed a relatively small number of cattle buyers to have a disproportionate control over the prices offered to livestock sellers. Economists call this situation—in which a few buyers control a market with many sellers—a monopsony. The Big Five quickly established monopsony power over livestock buying, complementing their monopoly power in beef marketing. Livestock sellers repeatedly complained that packer buyers at the major urban stockyards manipulated the price of cattle through illicit and arbitrary means. For instance, a Kansas livestock feeder in 1918 received a call from the yards in St. Joseph, Missouri, to ship as many cattle as possible for immediate slaughter. Sorting and loading a large cattle shipment took time, so the livestock feeder only managed to send four railcars on the first day, for which he received $14.85 per hundredweight. The next day he shipped the remaining 33 carloads, but received only $13.00 per hundredweight for the same quality of cattle—a price drop of $20 per head that made him regret the shipment.34

In popular discourse, the moniker “Beef Trust” represented all that was despised about this combination of monopoly and monopsony power. In a best-selling 1905 book, journalist Charles Edward Russell famously labeled the meatpackers the “Greatest Trust in the World” for their “great brute strength.” Even though dressed beef was generally cheap beef, the apparent ability of the Beef Trust to set prices based on their costs rather than according to the laws of supply and demand led consumers in cities throughout the country to blame the trust for any rise in price. Organizations such as the Ladies’ Anti-Beef Trust Association, formed in New York in 1902 to protest a 50-percent rise in meat prices, pointed an accusing finger at “the Trust” for “taking meat from the bones of your women and children.” Many consumers felt they simply could not trust the Beef Trust, located hundreds or thousands of miles away from the neighborhood meat shop. This was most famously illustrated by the public response to Upton Sinclair’s 1906 exposé of the Chicago meatpackers in his novel The Jungle. Intending to illustrate the plight of immigrant workers in the packinghouses, Sinclair instead disgusted his middle-class readers with images of rats scampering about the kill floors below vats of adulterated sausages. The book consequently helped lead to the 1906 passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act, but did not inspire the socialist political movement Sinclair had hoped for; as he later quipped, “I aimed at the public’s heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Nonetheless Sinclair’s work added to the growing consumer displeasure with the distant, unseen meatpackers and their power to affect daily food choices in nearly every city in the United States.35

Antitrust sentiment thus united both livestock raisers and urban consumers in their animus toward the Beef Trust, which reached the height of its unpopularity during World War I. Consumer concern over the soaring cost of living dominated the domestic politics of the war, with inflated food prices inflicting painful sacrifices for working- and middle-class consumers. Under pressure from both outraged consumers and from organized cattlemen, President Woodrow Wilson directed the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate the profits of the packing industry in 1917. The FTC report on the meatpacking industry, published in five thick volumes from 1918 to 1920, confirmed the worst suspicions of both consumers and cattlemen. The Big Five had garnered substantial profits during the war, averaging a 4.6 percent return on each dollar invested, or 350 percent more than prewar earnings. The FTC recommended sweeping government action to restore competition to cattle buying and beef marketing—outright public ownership of railroad livestock and refrigerator cars, terminal stockyards, and branch houses. Congress opted not to undertake this potentially expensive populist solution, so instead the Justice Department began antitrust proceedings against the Big Five in 1919. Facing both popular anger and the strongest government threat to date, the meatpackers capitulated in 1920, signing a Consent Decree. Under this agreement, the packers would not be prosecuted for violations of antitrust laws if they divested of their holdings in terminal stockyards, pulled out of the retail meat business, and agreed not to conspire to restrain interstate trade. Over the next several decades, however, the Consent Decree proved toothless. The big packers continued to expand their ownership of refrigerated railcars and branch houses in an effort to maintain market share. Despite the Consent Decree’s prohibition of mergers, the packers continued to absorb their competitors; in 1923, the Big Five became the Big Four when Armour bought out Morris. The packers also proved loath to dispose of their holdings in the public stockyards that provided them with their cattle supplies; by 1925, they had only sloughed one-quarter of their yards.36

The packers’ defiance pushed livestock producers to petition Congress for additional regulations, putting the USDA rather than the Federal Trade Commission in the driver’s seat of antitrust policy for the rest of the century. Seeking to bolster public confidence in the federal government’s ability to restrain the Beef Trust, Congress passed the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921. Congress intended the act to supplement the Consent Decree by conferring broad antitrust powers to the secretary of agriculture. The intent of the act was further clarified in 1922 when the Supreme Court affirmed its constitutionality, with Chief Justice William Howard Taft arguing that the “chief evil feared is the monopoly of the packers, enabling them unduly and arbitrarily to lower prices to the shipper who sells, and unduly and arbitrarily to increase the price to the consumer who buys.” In practice, however, the Packers and Stockyards Administration proved rather friendly to both the packers and the stockyards. Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace (the father of New Dealer Henry A. Wallace) publicly declared in 1922 that his department would “not assume that men are rascals until they have been proved to be such. We take it for granted that the various people who are under the supervision of this law will be glad to co-operate with us.” The problem of monopoly had become a significant state concern, but had not yet produced any effective state action.37

During the Great Depression, however, the meatpackers’ monopoly power took on added urgency, provoking farmers and consumers to push for antitrust action against the Big Four packers. While farmers received disastrously low prices for their cattle in the early 1930s, consumers found prices of fresh beef increasingly out of reach. The prices of sirloin steak and round steak, for instance, increased 5 percent between June and July of 1933. From August 1933 to August 1935, the average price of sirloin increased by more than a third, with round steak up 40 percent. At a time when up to one-quarter of the workforce was unemployed, such price rises forced many families to buy less meat. Between 1929 and 1935 per capita meat consumption dropped from eighty-five pounds to seventy-seven pounds, and with lowered consumption farmers suffered from lower cattle prices. Purchasing less meat was one form of resistance to high prices, but in a nation where beef had been transformed from a luxury to a prerogative of the American way of life, many consumers sought more active political solutions. In 1935, activists in New York, Detroit, and Boston organized extensive meat boycotts. Picketing housewives shut down butcher shops, demanded lower prices, and called for thorough investigations of the Beef Trust. The Women’s Auxiliary of the United Auto Workers mounted further protests against beef prices in 1937–38 in a nationwide campaign known as “No Meat Weeks.” Livestock raisers generally sympathized with consumers’ outrage, since high retail prices reduced demand. An Iowa cattle feeder, bewildered by rock-bottom cattle prices at a time when consumers could not afford to buy beef, wrote Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace in 1933 to offer his take on the problem: “I do not blame any one but the packing industry.”38

Faced with the protests of both cattle raisers and consumers, Henry A. Wallace came under constant pressure in the 1930s to use his antitrust power to deal with the Big Four’s apparent control of meat pricing. Ironically the first approach of New Deal agricultural policymakers was to consider relaxing antitrust efforts rather than strengthening them. With the milk marketing agreements as a model, agricultural policymakers gave significant thought to creating a legalized monopoly in beef marketing, providing the big packers with immunity from antitrust actions in exchange for a guarantee of higher prices to farmers and reduced prices for consumers. Economists believed this might be possible to achieve, considering that the big packers would have incentives to increase capital investments in their operations without fear of state intervention, thereby achieving greater economies of scale that would benefit farmers and consumers while still allowing a “reasonable profit” for the packers. Perhaps the most surprising advocate of this approach in 1933 was the liberal Jerome Frank, legal counsel for the AAA who was also active in crafting the milk marketing agreements. Writing to fellow liberals at the AAA—Rexford Tugwell, Mordecai Ezekiel, and Frederic C. Howe—Frank recommended in June of 1933 that the entire concept of antitrust be reexamined. Rather than consider the profit structures of the big meatpackers, Frank suggested a more appropriate strategy was to “restrict our attention to precisely computable savings affected by [economies of scale] and require that some portion of these savings be given to the farmer and some to the consuming public.” For a year, the USDA actively courted the meatpackers’ opinions on this approach through private negotiations led by Frank.39

Unsurprisingly the packers proved quite receptive to the idea. Frederick H. Prince, a majority stockholder in the Armour company and the Chicago Union Stock Yard, argued that “the most complete monopoly power that could possibly be granted” was necessary to achieve the New Deal goals of “fair profit on manufacturing” (a central tenet of the National Industrial Recovery Act) while still maintaining high farm prices (the main goal of the Agricultural Adjustment Act). Prince drafted a detailed proposal for this “most complete monopoly,” to be known as the Union Purchasing and Distributing Company. This company was to be owned by the Big Four packers and would “do all of the purchasing for the packers, fix the price to be paid for all commodities purchased, and have complete control of all shipments…. The company is also to fix the prices to be charged for all products sold.” According to Prince, retail prices of meat would plummet with the savings in transportation and distribution costs achieved by shared facilities.40