4 Human Health: Mercury’s Caduceus

Industrialization increased people’s exposure to a wide variety of hazardous substances, including mercury. Some adverse human health effects of this exposure, especially those that occur at high doses, are readily apparent to observers and have been known to science and medicine for centuries. Other effects can be more difficult to discern, especially at low levels of exposure, in part because health outcomes can be separated in time and place from the use and release of hazardous substances. Knowledge of the toxicity of specific substances and their human health impacts is distributed unevenly across the world and at different times. Societal risk perceptions and responses also differ: private sector actors and regulatory agencies assess costs and benefits and respond in varying ways to human health dangers. Hazardous substances such as mercury continue to pose a wide range of health threats, involving all parts of the planet that are inhabited by humans. Ensuring good health is a primary goal of sustainability, and addressing and managing health risks from the products of modern society will continue to be a central challenge for ensuring future human well-being.

Dr. Hajime Hosokawa and municipal health official Hasuo Itõ classified the first official case of Minamata disease on May 1, 1956, without knowing its cause (George 2001). Local fishers had complained for several years that wastewater dumped into Minamata Bay from a local factory was killing fish, and they observed how cats that had eaten fish would dance crazily, jump into the sea, or die (Harada 1995). The fishers and their family members suffered from numbness, visual and hearing impairments, and loss of motor control, among other symptoms, and some had died (Takeuchi et al. 1959). The local committee to address the unknown problem, known as the Strange Disease Countermeasures Committee, designated the first 52 certified victims on December 1, 1956. By that date, 17 victims had died. Leaders of the local factory denied all responsibility for causing the illnesses, and held back information on their use and releases of mercury; the factory, owned by the Chisso Corporation, had used mercury as a catalyst to produce acetaldehyde since 1932 and to manufacture vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) since 1941. As local tensions grew, the Minamata-born poet Gan Taginawa suggested a parallel between Dr. Hosokawa and the small-town doctor in Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People, who was attacked for pointing out polluted water in the town spa, an enterprise critical to the tourist industry (George 2001).

City, prefectural, and national officials as well as many local residents who depended economically on the factory defended Chisso. One of those defenders was Hikoshichi Hashimoto, the mayor of Minamata, who had himself developed the mercury-based acetaldehyde production technique when he previously worked at the factory. The Japanese government did not officially acknowledge that pollution from the factory had caused Minamata disease until September 1968, a few months after Chisso had stopped using mercury in acetaldehyde production. The company continued to use mercury in VCM production until 1971. In 1969, 112 people representing 29 families filed a lawsuit against Chisso in Kumamoto District Court. Four years later, the court found Chisso responsible and established that all certified patients had a right to compensation. But many people who fell ill struggled to get certified. The legal process continued until 1988, when the Japanese Supreme Court found a former Chisso president and factory manager guilty of negligent homicide and gave them suspended two-year prison sentences. After an extensive remediation that involved removing contaminated sediments, the governor of the Kumamoto prefecture declared the fish in Minamata Bay safe for consumption in 1997, more than 40 years after the formal identification of the first Minamata disease patient.

The story of methylmercury poisoning in Minamata, where hundreds of people died, illustrates risks from the millennia-long relationship between mercury and human health. That relationship has manifested in two main ways. First, people have used mercury in medicine, with mixed results, in an attempt to improve well-being and longevity. Second, occupational and dietary exposure to mercury has caused severe health damages. In the title of this chapter, we echo the (often ill-advised) use of mercury in many medical therapies by referring to the irony in the mistaken use of the caduceus of Hermes (the Greek equivalent to Mercury) in place of the similar-looking rod of Asclepius as a symbol of the medical profession. Asclepius is the god of medicine, while Hermes/Mercury is the god of commerce and thieves. Asclepius’s rod features a serpent entwined around it; the caduceus features two serpents around a winged staff. Hermes’s caduceus was adopted in 1902 as the insignia for US Army medical personnel, for example. The mix-up between the two symbols goes beyond visual similarity, however, to suggest the complicated symbolism of the serpent throughout history, as a creature possessed of destructive and healing powers alike (Prakash and Johnny 2015).

Mercury harmed people in both preindustrial and industrial societies, and continues to adversely affect people throughout the world today. Mercury’s health impacts vary with both the forms and the amounts of mercury people are exposed to. The challenges of mobilizing actions to address mercury’s risks and impacts have changed with time. People adversely affected by mercury pollution have clashed with powerful economic and political interests when looking for support and compensation. In the case of Minamata, it took decades before the Chisso Corporation and relevant authorities took meaningful action to stop discharges of methylmercury into Minamata Bay. Negative health problems from mercury continue to affect populations living far away from any emission source—especially pregnant women and small children—who are nevertheless at risk from long-range transport of emissions and exposure because of the food they eat. Discussions about the burdens of human exposure and the strategies and costs of mitigation, from local to global scales, continue today in the context of the implementation of the Minamata Convention, which also recognizes future generations as a particularly vulnerable group of people.

In this chapter, we examine how human health is affected by mercury and mercury compounds, and we consider measures taken to reduce negative health impacts from mercury. First, in the section on system components, we outline how human, technical, and environmental components influence how people use and are exposed to mercury, and how institutions and knowledge are linked to mercury as a human health issue. In the section on interactions, we detail pathways by which the societal use of mercury and its presence in the environment harms human health through occupational, medical, and dietary exposure. Our discussion of interventions focuses on efforts to address mercury-related health problems, including those that have been taken to address high-dose occupational exposure in particular types of workplaces, to phase out mercury use in medicine, and to mitigate harms from low-dose dietary exposure from seafood. In the final section on insights, we look at how mercury’s inherent properties and system interactions influence mercury-related human health problems, how changing perceptions of the way mercury affects people’s health have led to largely incremental efforts to mitigate these impacts, and the need for multi-scale governance strategies to effectively address mercury’s human health dangers.

System Components

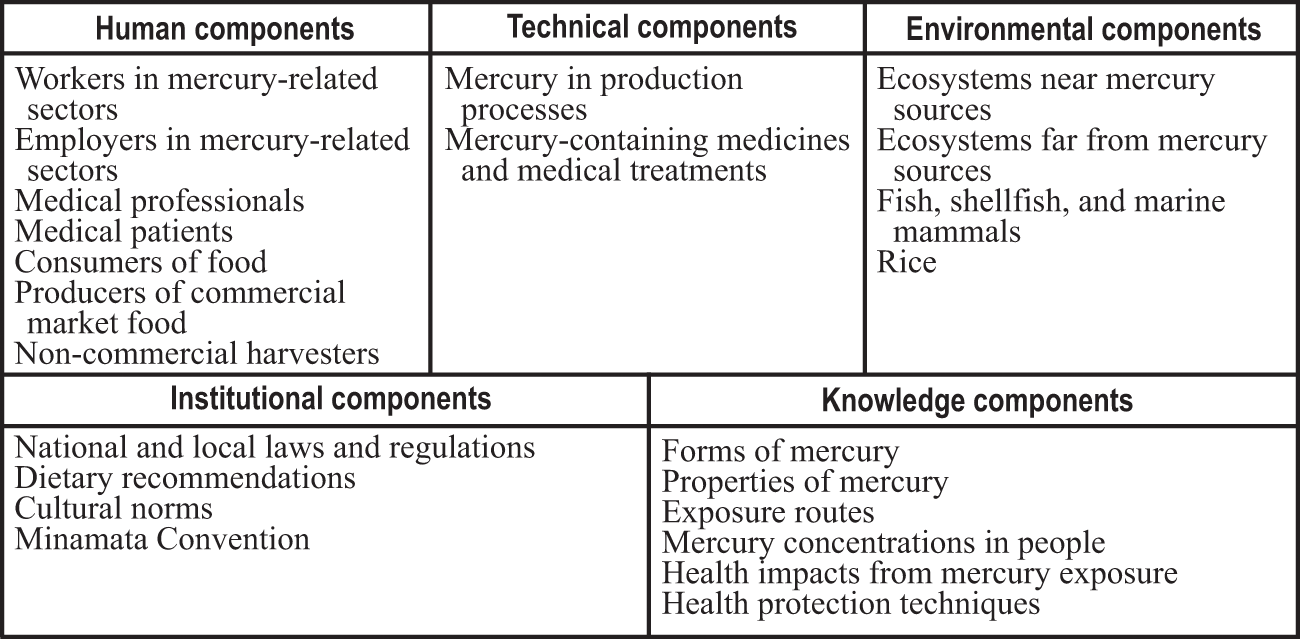

Mercury exposure has posed a threat to human health for millennia. It remains a current problem, and it will continue to be problematic for many generations to come. The forms of elemental mercury and mercury compounds that we discussed in chapter 3 have different levels of toxicity, with important implications for human exposure and health. People are exposed to varying levels of different forms of mercury. Exposure to both inorganic and organic mercury can be short-term or long-term and thus manifest as acute or chronic poisoning. The phrase “the dose makes the poison” applies to all forms of human exposure to mercury. That famous phrase itself is attributed to the Swiss physician Paracelsus (1493–1541), and has its roots in his laboratory work with mercury (Grandjean 2016). Figure 4.1 shows the main human, technical, environmental, institutional, and knowledge components for the mercury and health system.

Components in the mercury and health system (referenced in the text in italic type).

People have come in direct contact with mercury in production processes as workers in mercury-related sectors. Most of this exposure, going back thousands of years, was to inorganic mercury and its compounds, including elemental mercury. Knowledge of how different forms of mercury have affected human health has developed over time; health effects resulting from exposure have long been observed in miners and other workers. For example, hat-makers who started to use a mercury-based felting technique in the seventeenth century suffered from repeated and dangerous exposure to mercury. It is often thought that the character known as the Mad Hatter in the nineteenth century books of Lewis Carroll behaved strangely because of mercury poisoning. Others believe instead that Carroll modeled the character on an eccentric furniture dealer and amateur inventor named Theophilus Carter, but the saying “mad as a hatter” nevertheless remains a common colloquial expression in English (Waldron 1983). Additional workers who faced particular risks from mercury use included gilders, potters, tinsmiths, painters, glass workers, mirror makers, and scientists (Goldwater 1972). Industrialization increased the number of workplaces in which workers were exposed to mercury, where employers in mercury-related sectors largely determined workplace conditions and thus potential mercury exposure.

Medical professionals have prescribed and applied mercury-containing medicines and medical treatments to medical patients over a long history. Shen Nong, the mythological father of Chinese medicine who was credited with writing the 40-volume Great Herbal in the twenty-eighth century BCE, included mercury among the many drugs he listed (Hayes and Kruger 2014). Early writings indicate that mercury was also used for medical purposes in ancient India, Greece, and Rome, and later in the Arab world and in medieval Europe (Goldwater 1972). The Greek physician Hippocrates (460–370 BCE), known for the Hippocratic oath that still guides the actions of doctors, was likely to have prescribed mercury compounds as ointments. The use of mercury-containing salves for treating skin lesions continued into the second half of the twentieth century (Goldwater 1972). Calomel (mercurous chloride) and other mercury compounds were used to treat a wide range of illnesses, including syphilis beginning in the fifteenth century. Calomel was also used in laxatives. Using cinnabar to tattoo the surrounding area was a treatment against pruritus ani (intense anal itching) by medical doctors well into the twentieth century (Granet 1940).

Mercury and mercury compounds were also used in other medical areas. Mercuric chloride was applied as an antiseptic to disinfect wounds, including during World War I and World War II (Hylander and Meili 2005). Phenylmercury compounds were used as disinfectants based on their ability to prevent bacterial growth. They were also used as vaginal spermicides beginning in the 1930s (Baker et al. 1939; Löwy 2011). Dental use of mercury likely began in China in the first century CE, and physicians in China and Europe wrote about its use in amalgam in the sixteenth century (Bharti et al. 2010). Mercury-based dental amalgams are still used to restore teeth affected by dental caries. Ethylmercury thiosalicylate (thimerosal, or thiomersal outside the United States) was introduced into vaccines in the 1930s as a preservative to prevent growth of bacterial and fungal contaminants (Baker 2008). Thimerosal is still used when vaccines against diseases including diphtheria, hepatitis B, and influenza are distributed in multiple-use vials where repeated syringe insertions can cause contamination (Clarkson and Magos 2006; World Health Organization 2011b). Thimerosal and other mercury compounds have also been used as preservatives in very small amounts in pharmaceuticals such as ear and eye drops, contact lens solution, nasal spray, and hemorrhoid relief ointment (US Environmental Protection Agency 2020).

People around the world are exposed to methylmercury as consumers of food, predominantly seafood, whether harvested from ecosystems near mercury sources or ecosystems far from mercury sources. The mercury in fish, shellfish, and marine mammals sometimes comes from local sources, as was the case in Minamata, but it can also come from long-range transport. The fish that people consume in modern societies originate from many different locations, as producers of commercial market food may sell their fish and shellfish worldwide. People are also exposed to mercury by eating seafood caught by non-commercial harvesters. For example, consumers of community-harvested marine mammals and whales in places such as the Faroe Islands and the Arctic are exposed to particularly high doses of methylmercury, as are subsistence fishers who catch their food in waters near point sources and contaminated sites. Methylmercury has also been measured in rice, where rice plants that are cultivated in submerged or flooded paddies have the ability to take up methylmercury (Meng et al. 2014; Kwon et al. 2018). This can be the dominant source of dietary mercury for some consumers of large quantities of rice where mercury concentrations are elevated.

Understanding the human health impacts of mercury depends on knowledge of the properties of mercury, different human exposure routes of mercury, and mercury concentrations in people. In living people, measuring mercury levels requires taking samples of bodily fluids or tissues. Urine is often used to identify elemental mercury exposure, whereas hair concentrations are a preferred indicator of methylmercury exposure (Clarkson et al. 2007). Both elemental and methylmercury have a half-life in the human body of a few months (Clarkson et al. 2003). Elemental mercury is most dangerous when it is inhaled in its gaseous form: it largely passes through the body when ingested in its liquid form (Ha et al. 2017). In contrast, methylmercury is almost completely absorbed into the bloodstream via the gastrointestinal tract (Mergler et al. 2007). Methylmercury travels throughout the body, including to the brain and to a developing fetus (Clarkson et al. 2007). Mercury is present in all people, but those who live near artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) activities and indigenous peoples in the Arctic have relatively high methylmercury concentrations, and elevated levels have been measured in seafood consumers in the Asia/Pacific region and the Mediterranean (Sheehan et al. 2014).

Knowledge of the health impacts from mercury exposure has developed through time. The term “erethism” was used until the early nineteenth century to describe the impacts of inorganic mercury exposure (Clarkson and Magos 2006). Its principal features were excessive timidity, increasing shyness, a desire to be unobtrusive, and anxiety. H. A. Waldron (1983, 1961) notes that victims of mercury poisoning “had a pathological fear of ridicule and often reacted with an explosive loss of temper when criticized.” High exposure, for example at levels experienced by miners, led to fatalities. Symptoms of organic mercury poisoning are different. Starting with numbness of the hands and feet, subsequent symptoms include lack of muscle coordination, loss of vision and hearing, and other signs of rapidly increasing damage to the central nervous system (Clarkson and Magos 2006). High dose exposure to methylmercury can be lethal. Methylmercury at low doses can cause neurological effects on small children and developing fetuses. Other kinds of health effects, for adults exposed to low doses, include cardiovascular problems, impacts on endocrine function, risks of diabetes, and immunological impacts (Eagles-Smith et al. 2018). Knowledge of health protection techniques, including occupational safety measures such as increased ventilation and wearing gloves and masks, can help limit exposure to some forms of mercury.

Institutions such as national and local laws and regulations include provisions that address mercury use in workplaces and in medicine, and also set labor and food safety standards related to mercury exposure. Governments and non-governmental organizations have issued dietary recommendations in the form of advice on the consumption of specific species of fish and types of seafood. Recommendations like these are designed to reduce human exposure and mitigate mercury risks, especially among more vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, small children, and people who regularly consume food containing relatively high levels of methylmercury. Dietary exposure to methylmercury can be influenced by long-standing cultural norms, especially for people in indigenous and other communities who hunt and consume seafood and marine mammals as part of their traditions and traditional diets. The Minamata Convention acknowledges the important link between mercury and human health, and contains several health-related provisions that are intended to guide its implementation in countries.

Interactions

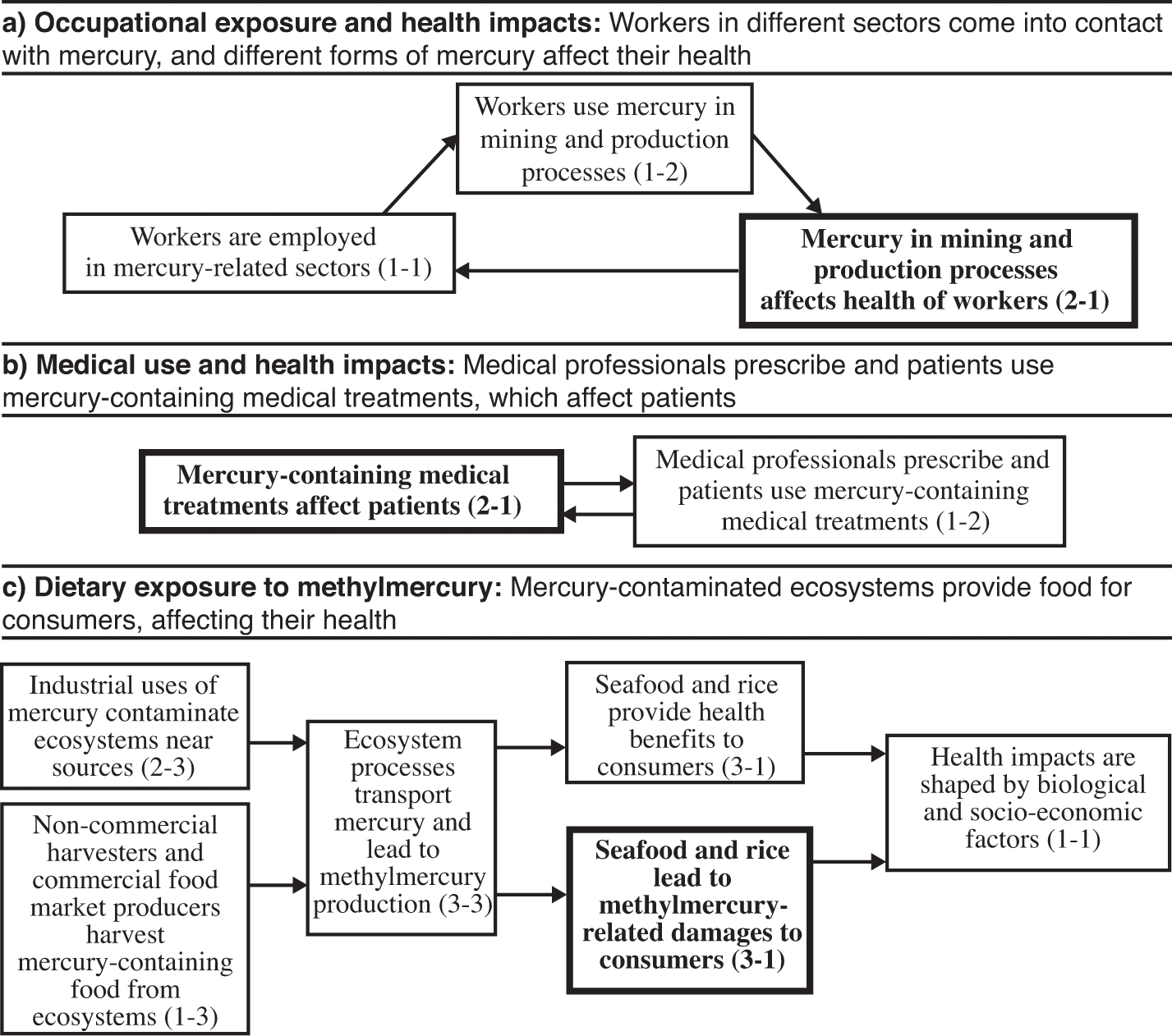

Mercury use and exposure affects human health in several different ways. Figure 4.2 shows interactions in the mercury and health system. We have selected three interactions in that matrix (the items in bold type in boxes 2-1 and 3-1) through which mercury affects people’s health; we then trace the pathways that influence these interactions, which we summarize in figure 4.3 (where the bold boxes correspond to the selected interactions). First, mercury in mining and production processes affects the health of workers (box 2-1), and this is determined by their employment in mercury-related sectors and use of mercury (boxes 1-1 and 1-2). Second, mercury-containing medical treatments affect patients (box 2-1), and this is influenced by the actions of medical professionals (box 1-2). Third, methylmercury-contaminated food affects consumers (box 3-1), as mercury is transported and transformed through ecosystems where human health impacts also depend on biological and socio-economic factors (boxes 2-3, 3-3, 1-3, 1-1, 3-1).

Interaction matrix for the mercury and health system.

Pathways of interactions for the mercury and health system. Bold box indicates focal interaction for each subsection.

Occupational Exposure and Health Impacts

Mercury in mining and production processes has affected the health of workers for millennia (box 2-1). As we mentioned in chapter 3, cinnabar may have been mined in Turkey at least as early as 6300 BCE, making miners some of the earliest workers employed in mercury-related sectors (box 1-1). Mercury mining in the Wanshan district in southwestern China goes back two millennia. The mine in Almadén, similarly, is believed to have been in operation for 2,000 years—the first known recorded reference to mining in the area dates back to the fifth century BCE (Coulson 2012)—and may have produced one-third of all mined mercury in the world. Mercury mining in Idrija began in the late fifteenth century. The various operators of the Almadén and Idrija mines used slaves, convicts, and salaried workers at different times to mine for cinnabar under extremely harsh conditions. One reason for the hazardous working conditions was that the mercury in the mines was not only embedded in cinnabar but also present in the ores as droplets of liquid elemental mercury large enough to be visible to the naked eye. This liquid form of elemental mercury was quick to volatilize into its much more dangerous gaseous form under the very warm conditions in mine shafts, with mercury vapor quickly reaching dangerous levels in the narrow and crowded shafts deep underground (Hamilton 1943).

Much human suffering also took place in the mercury mine in Huancavelica, Peru. Colonial Spanish rulers appropriated this mine in 1563 from the Inca, who had used it as a source of vermilion (Robins 2011). The Spanish introduced a mandatory system called the mita to conscript Indian labor into the mercury mine. This devastated indigenous populations through a combination of high mortality rates in mining and the flight of laborers to avoid conscription (Robins 2011). Potential miners considered a two-month stint at Huancavelica a death sentence: mercury exposure combined with accidents, the inhalation of silica dust, and carbon monoxide poisoning gave Huancavelica a reputation as the mina de la muerte (the mine of death) (Brown 2001, 468). Mercury mining expanded in the United States starting in the 1800s, including in the mines in New Almaden and New Idrija in California, feeding a growing demand from the gold rush. Mercury from large mercury mines further exposed many additional workers in the mining sector when it was subsequently used in silver and gold mining (box 1-2). We further discuss mercury use in contemporary ASGM in chapter 7.

Adverse human health impacts of mercury exposure were also seen in workers in other sectors, going back at least five hundred years, as workers used mercury in production processes (box 1-2). The doctor Ulrich Ellenbog expressed one of the earliest known concerns in a 1473 pamphlet, writing about the risk to goldsmiths of inhaling mercury vapor in his city of Augsburg, Germany (Goldwater 1972). In the German city of Fürth in 1885, 72 percent of the 7,500-plus sick days taken by mirror makers were reportedly the result of mercury poisoning (Teleky and Kober 1916). Effects of mercury poisoning were also frequently observed in hat makers who used a mercury-based fur-felting technique that was developed in France in the 1700s. This revolutionary technique for making fur hats subsequently spread to other European countries and continents. In the United States, Danbury, Connecticut, became known as “the Hat City of the World” in the mid-1800s (Wajda 2019). The tremors that workers in the many hat factories there experienced from mercury exposure gave rise to the expression “the Danbury Shakes” (Hightower 2009).

Worker exposure to mercury in several manufacturing industries continued, and in some cases increased, during the twentieth century. These industries included hat making as well as the production of mercury lamps and several kinds of manufacturing processes, which we discuss further in chapter 6. Incidents occurred in other workplaces as well. Several people at a seed packing facility in Norwich, England, in the 1930s were poisoned by methylmercury that was used as a disinfectant and preservative to protect seeds against mold (Hunter et al. 1940). Furthermore, members of the Lancashire Constabulary in England who specialized in taking and developing fingerprints using a mixture of mercury and chalk powder were found in 1949 to suffer from the effects of mercury exposure. Their symptoms included tremors in their hands, lips, tongue, and eyelids as well as loose teeth and “irritability and embarrassment which caused the men to blush easily” (Anonymous 1949, 231).

Health problems from industrial mercury use continue in more recent times. In one high-profile case, workers were exposed to mercury in a thermometer factory that was built in 1983 in Kodaikanal in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. This factory was built with equipment from a decommissioned US plant, and was initially operated by the US company Chesebrough-Pond’s. Former workers from the factory show symptoms of mercury vapor poisoning, and this exposure has been linked to premature deaths (Dev 2015). The Tamil Nadu Pollution Board forced manufacturing to shut down in 2001 after public protests. Advocates fought for compensation for exposed workers from the Indian subsidiary of the British-Dutch conglomerate Unilever, which had acquired the factory from Chesebrough-Pond’s in the 1990s. An out-of-court settlement was eventually reached in 2016, providing an undisclosed amount of compensation to 591 former workers (Agnihotri 2016).

Alchemists and scientists are another category of workers extensively exposed to mercury. Paracelsus, Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580–1644), Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), and Michael Faraday (1791–1867) are all thought to have suffered from chronic mercury poisoning without realizing what caused their condition (Giese 1940; Goldwater 1972). The difficulty in identifying mercury as the source of illness is influenced by the fact that mercury vapor is colorless and odorless, and symptoms can be caused by many different factors. Another person whose health has been alleged to have been affected by mercury is Isaac Newton (1643–1727), an avid alchemist who used mercury extensively in his experiments. Some scientists have speculated that the psychological illnesses Newton suffered in 1693 were a result of mercury poisoning (Broad 1981). Analysis of Newton’s hair centuries after his death revealed levels of mercury high enough to suggest that Newton suffered from chronic mercury poisoning (Johnson and Wolbarsht 1979). Other scientists, however, have questioned not only these measurements but also whether Newton’s symptoms were consistent with mercury poisoning or stemmed from other causes (Ditchburn 1980).

The documentation of health effects in scientists from mercury use and exposure in laboratories increased in the twentieth century. In 1926, the German chemist Alfred Stock wrote a vivid firsthand account of “insidious mercury vapor poisoning” that he and his colleagues suffered from for decades without knowing what caused their illness. Symptoms included memory loss; headaches; nervous restlessness; strong vertigo and visual disturbances; nose, throat, and sinus infections; loosening of teeth; sudden bladder pressure; and isolated bouts of diarrhea (Stock 1926). Scientists nevertheless continued to work with mercury. Clark Goodman at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology noted in 1938: “Mercury is such a common laboratory companion that little consideration is usually given to the possibility of the toxic effects which may result from handling it or from breathing the vapor which is inevitably emanating from the liquid metal” (Goodman 1938, 233). Gradually, scientists became more aware of the health risks. Arthur Giese at Princeton University warned in Science in 1940 about the dangers of mercury vapor in air in closed laboratories (Giese 1940).

Much of the human health concern expressed about the laboratory use of and exposure to mercury involved its metallic and inorganic forms, but scientists were also among the first workers who were exposed to organic mercury. When methylmercury compounds were first synthesized in London in the 1860s, two laboratory technicians died from poisoning (Clarkson 2002). In a more contemporary case with a lethal outcome, Karen Wetterhahn, an organometallic chemist and professor at Dartmouth College, died in 1987 from exposure to one or two small drops (less than half a milliliter) of dimethylmercury (Science News Staff 1997). This highly dangerous form of organic mercury penetrated not only the latex gloves she wore in the laboratory but also her skin. Her illness became apparent five months after the accident as it affected her balance, speech, vision, and hearing. Her condition worsened; she fell into a coma and then passed away 10 months after the minuscule spill (Clarkson and Magos 2006).

Medical Use and Health Impacts

Over long periods of time, mercury-containing medical treatments have affected patients (box 2-1). The intentional use of mercury in medicine began more than 2,000 years ago, and persisted through time. Exposure occurs when medical professionals prescribe, and patients use, mercury-containing medical treatments for various ailments (box 1-2). Chinese emperor Qin Shihuang, looking to discover an elixir of immortality, ingested a large quantity of cinnabar (Dubs 1947). This may have contributed to his death at age 49 in 210 BCE (Wright 2001). US president John Adams complained about mercury treatment for smallpox causing his teeth to loosen (US National Archives 2019); some historians have hypothesized that his contemporary, George Washington, may also have lost his teeth in part because of calomel use for smallpox or other ailments (George Washington Foundation 2017). Members of the Lewis and Clark expedition that started in 1804 from St. Louis carried 50 dozen laxative pills containing calomel made by Benjamin Rush, a renowned colonial physician and a signer of the US Declaration of Independence. The effectiveness of these pills earned them the nicknames “Thunderbolts” and “Thunderclappers” (Woodger and Toropov 2004). Two hundred years later, their use helped researchers trace part of the route of the expedition, by identifying latrine pits with elevated mercury levels (Fessenden 2015).

Mercury-containing medicines were extensively used in the past against syphilis. Calomel was administered to syphilis patients beginning in the fifteenth century by rubbing it on the skin, as well as by fumigation or in oral form (Goldwater 1972). Patients were often treated while sitting in a tub, and the children’s rhyme “rub-a-dub-dub, three men in a tub” is thought to be a reference to syphilis treatment (Magner and Kim 2017). Another remedy included wearing underpants coated on the inside with mercurial ointment (Parascandola 2009). High-dose applications of mercury for syphilis treatment led to mercury poisoning, but doctors and patients often mistook the symptoms for those of syphilis itself. It was also thought that these highly toxic and agonizingly painful treatment methods for syphilis were “peculiarly appropriate for a disease that was commonly regarded as the wages of sin” (Snowden 2006, 144). Drugs for syphilis were also prescribed for other ailments. Novasurol, for example, containing almost 34 percent mercury, and first introduced by Bayer in the early 1900s to treat syphilis, became widely used as a diuretic starting in the 1920s (Anonymous 1926). It was seen as an effective part of treatment for liver cirrhosis and kidney failure despite reports of fatalities from the 1930s onward. Novasurol may not have caused all of these deaths, however, because the drug was largely given to people with already severe and life-threatening conditions (Goldwater 1972).

Mercury compounds had several other medical uses in the twentieth century. Mercury solutions and ointments were used, for example, by US soldiers beginning in World War I to protect against the spread of venereal diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea. Soldiers were required to report to army prophylactic stations no later than three hours after sexual contact (Tone 2002). As part of the standardized treatment process, their genitals were washed with a solution of bichloride and mercury, liberally smeared with a calomel ointment, and wrapped in wax paper (Farwell 1999; Shaffer 1920). One treatment for those afflicted with gonorrhea involved injecting a solution containing mercury compounds into the urethra (Young et al. 1919). Starting in the 1930s, phenylmercury compounds were active ingredients in contraceptive suppositories, gels, and foams used by women. The product Volpar, for example, became commercially successful, and contraceptive uses of mercury compounds continued for decades (Löwy 2011). In addition, mercurochrome, the trade name for the phenylmercury compound merbromin, a red-colored disinfectant, was widely applied to prevent infection from minor cuts and scrapes.

In one particularly ill-fated study with human subjects, mercury was administered in an attempt to combat malaria (Snowden 2006). Two Italian researchers—Giacomo Peroni and Onofrio Cirillo—gained Mussolini’s personal approval in 1925 to carry out an experiment on workers in Apulia and Tuscany, two areas where malaria was endemic. The effort to eradicate malaria was a central part of the Fascist revolution, and the two researchers were convinced that mercury was a better remedy against malaria than quinine. Against established medical expertise, in a four-year project ending in 1929, a first group of workers received no treatment even though many of them suffered from life-threatening malaria. A second group of workers received mercury through intramuscular injection. In total, 395 people with malaria were administered mercury as an alleged treatment. Peroni and Cirillo claimed that their study was a great success, and wanted to treat the entire Italian army with mercury injections. However, an outside medical expert hired by the Italian authorities forcefully rejected all their findings, and their suggestion of mass vaccination with mercury was never carried out.

The use of mercury in medicine is linked to many additional unintended health problems. This includes the disease acrodynia in children, which was caused by chronic exposure to calomel and other mercury compounds in teething powders, in treatments against intestinal worms, and as diaper disinfectants. Also known as pink disease, acrodynia manifested itself through pink discoloration of hands and feet as well as painfully inflamed nerves and sensitivity to light—“a typical picture is that of a child with head buried in a pillow and continually crying” (Clarkson 2002, 16). Cases of acrodynia were recorded in Europe beginning in the late 1800s, and later also in Australia and North America, with documented fatalities up until at least the 1950s (Dally 1997). It remains unclear exactly why, but only some of the mercury-exposed children developed acrodynia. Symptoms could last for weeks and months, and the disease had an estimated mortality rate of 10 percent in the early twentieth century. It took roughly half a century for researchers to make the connection to calomel, and evidence suggests that at least some adult survivors suffered from chronic chest disease and infertility (Dally 1997; Black 1999).

Acute health effects have also been observed when people have taken mercury-containing medicines without medical prescriptions and recommendations (Goldwater 1972). This included people swallowing mercuric chloride tablets, having mistaken them for other (less harmful) pills. In other cases, people intentionally swallowed mercury-containing tablets for suicidal purposes. One study noted that in 1934, mercury was the fifth most common substance detected in poisoning cases at the Montreal General Hospital, behind lead, morphine, carbon monoxide, and alcohol (Rabinowitch 1934). In addition, pregnant women have taken cinnabar and other mercury compounds in attempts to induce abortions (Goldwater 1972; Severyanov and Anisimova 2013). People have even committed murders using highly toxic mercury salts such as mercuric chloride (Blum 2011). In Germany in 2019, a worker was sentenced to life in prison for using methylmercury and other toxic substances to poison his coworkers’ lunch sandwiches. One of his victims was in a coma with serious brain damage for four years before passing away; others suffered lasting kidney damage (Schuetze 2019; Stegemann 2019; Anonymous 2020).

Some mercury-containing medicines and medical treatments, together with the use of mercury-containing medical devices such as thermometers and sphygmomanometers, have had positive impacts on human health (see chapter 6). Mercury use in dental amalgam provided an effective treatment for dental cavities, greatly improving the ability of dentists to repair damaged teeth with many benefits for oral health. The antimicrobial properties of thimerosal and other mercury compounds have made them effective preservatives for different kinds of medical products, including vaccines as well as eye and ear drops. Historically, expanded vaccination has had tremendous health benefits in preventing the spread of serious and sometimes lethal diseases worldwide, and the presence of very small amounts of mercury facilitates the transport to, and use of, vaccines in remote areas. The application of eye and ear drops addressed a wide range of conditions for a large number of patients. All of these largely beneficial uses of mercury continued into the twenty-first century.

Dietary Exposure to Methylmercury

Seafood and rice consumption can lead to methylmercury-related health damages to consumers (box 3-1). As was the case in Minamata, industrial uses of mercury can contaminate ecosystems near sources (box 2-3). People who do not live near a major point source can still be exposed to dangerous levels by consuming seafood containing high levels of methylmercury because ecosystem processes transport mercury and lead to methylmercury production (box 3-3). As a result of such long-range transport, aquatic ecosystems far from point sources can contain much methylmercury. Non-commercial harvesters as well as commercial food market producers harvest mercury-containing food from ecosystems (box 1-3). Whale consumers in places such as the Faroe Islands and indigenous peoples in the Arctic can be particularly highly exposed, because they eat marine mammals that are high on the food chain, and methylmercury biomagnifies and bioaccumulates. People in all regions of the world who purchase and consume seafood from commercial markets are exposed to methylmercury, but in some places like China, exposure from contaminated rice can also be important (Rothenberg et al. 2014).

A recent study from the United States showed that roughly 45 percent of methylmercury exposure to the US population comes from consuming fish from the open ocean, 37 percent from domestic coastal systems, and 18 percent from aquaculture and freshwater fisheries (Sunderland et al. 2018). More than 95 percent of mercury in predatory fish is methylmercury, while the fraction that is methylmercury in shellfish can be lower (Bloom 1992; Sunderland et al. 2018). Methylmercury concentrations are particularly elevated in marine mammals and large fish, such as tuna and swordfish, near the top of food webs. Data from adult American women suggested in the early 2000s that more than 300,000 babies were born annually to women whose mercury levels exceeded the US guidelines intended to protect against adverse neurodevelopmental effects (Mahaffey et al. 2003). More recent studies suggest this number may have declined: although data from 1999 to 2000 showed that 7 percent of women had mercury concentrations above guideline levels, only 2 to 3 percent of women had concentrations that high in subsequent studies up to 2010 (Birch et al. 2014).

Ingesting very high doses of methylmercury through eating contaminated fish leads to symptoms like those seen in the victims of Minamata disease. A Swedish expert group, assessing evidence from Minamata and a similar poisoning case in Niigata, Japan, concluded that clinical symptoms of methylmercury poisoning occurred at blood levels above 200 micrograms mercury per liter, and with concentrations in hair as low as 50 parts per million (Swedish Expert Group 1971). These clinical symptoms include severe neurological symptoms such as numbness and paralysis and permanent damage to the nervous system (Clarkson and Magos 2006). In some other places that were not contaminated by a local point source, people who consumed large amounts of high-mercury fish were reported to have experienced deleterious effects (Korns 1972; Silbernagel et al. 2011). In a well-publicized but unverified case, the actor Jeremy Piven in 2008 stepped down from his role in the Broadway show Speed-the-Plow due to fatigue and exhaustion, which he claimed stemmed from high levels of mercury from eating large quantities of sushi and other forms of fish (Itzkoff 2008).

Exposure to methylmercury at lower doses also has health impacts, especially for fetuses and newborn children whose mothers were exposed to methylmercury during pregnancy. Much scientific evidence on the dangers of low-dose exposure comes from epidemiological studies in the Faroe Islands, where people have harvested and consumed large amounts of pilot whale meat and blubber since at least the sixteenth century (Fielding et al. 2015). In the present day, whale meat and blubber contain high levels of methylmercury. Studies that tracked children in the late 1990s linked prenatal exposure to methylmercury to cognitive deficits years later (Grandjean et al. 1997). Two other similar large-scale studies were also conducted around the same time. One of these (in New Zealand) found evidence of neurological impacts from methylmercury exposure while the other (in the Seychelles) did not (US National Research Council 2000). An integrated analysis of data from all three studies found a relationship between increased mercury exposure and decreased IQ (Axelrad et al. 2007). More recent epidemiological data show that methylmercury exposure may lead to neurological impacts at even lower doses than previously thought (Grandjean 2016). No threshold has been identified below which methylmercury exposure is safe (Sunderland et al. 2016).

Developing research since the 2000s shows that low-dose exposure to methylmercury can also harm adult non-pregnant fish consumers. Knowledge of low-dose methylmercury effects in adults is less certain than the effects that have been scientifically documented in newborns and small children in the epidemiological studies in the Faroe Islands and elsewhere. Nevertheless, there is scientific evidence that methylmercury is also damaging to adults (Sunderland et al. 2016). Evidence for methylmercury’s cardiovascular impacts continues to grow (Roman et al. 2011; Genchi et al. 2017). Studies have also demonstrated that methylmercury can cause damage to the immune system and the reproductive and endocrine systems, and increase risks for diabetes (Eagles-Smith et al. 2018). In addition, methylmercury has been identified as a possible carcinogen (US National Research Council 2000).

Health impacts from the dietary intake of methylmercury are shaped by biological and socio-economic factors (box 1-1). Scientific knowledge about such relationships is relatively recent, and still emerging (Eagles-Smith et al. 2018). Studies reveal that certain genetic characteristics—variations in a single element of a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence—can either enhance or decrease the impact of toxic substances (Basu et al. 2014). This has been shown to be important for mercury, where certain genetic variations are associated with higher and lower mercury levels in exposed populations, and thus with differing adverse health outcomes. Because the timescale of human health impacts from methylmercury can stretch across generations, a growing area of research involves epigenetics, which refers to genetic changes that can be inherited without underlying alterations in DNA (Baccarelli and Bollati 2009). Epigenetic changes as a result of environmental contaminants can have long-lasting, multigenerational impacts (Feil and Fraga 2012). Evidence of epigenetic effects is emerging in the case of mercury (Basu et al. 2014).

A number of studies in different parts of the world have estimated the population-wide impacts of low-dose exposure to mercury in different countries on IQ deficits as well as cardiovascular damages. Some researchers have extended this work to calculate monetary costs as a result of these exposures, or the monetary benefits of action to reduce exposure. One study estimated the burden of mercury pollution for population-wide IQ damages in Europe to be between 8 and 9 billion euro (Bellanger et al. 2013). In the United States, median cumulative benefits estimated in monetary terms to the year 2050 as a result of policies implemented under the Minamata Convention could reach over USD 300 billion (Giang and Selin 2016). For China, the benefits of reducing mercury exposure via emission reduction policies by 2030 were calculated to exceed USD 400 billion (Zhang et al. 2017). These estimates use different methods of analysis, and are not strictly comparable, but taken together they suggest that although the economic burden of mercury exposure in multiple regions of the world is large, it can be reduced. These benefits can far exceed the costs of reducing mercury emissions (Sunderland et al. 2018).

Seafood and rice also provide many health benefits to consumers, as these foods can be critical sources of important nutrients (box 3-1). These nutrients, including n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs), have been shown to have positive benefits for brain and visual system development in infants and reduce risks of certain forms of heart disease in adults (Mahaffey et al. 2011). If people stop eating fish or other forms of seafood, the reduction in the consumption of fatty acids, antioxidants, vitamins, and protein must be made up for with other food choices (Fielding 2010). In many indigenous communities, such as in the Arctic and around the Great Lakes on the US-Canadian border, fishing and eating fish and other kinds of seafood are not only important from a dietary perspective, but also economically, socially, and culturally (AMAP 2011; Gagnon 2016). In addition, for many people in the Faroe Islands, the communal hunting of pilot whales (the grindadráp) and the consumption of whale meat and blubber is a proud tradition linked to their national identity (Fielding et al. 2015).

Interventions

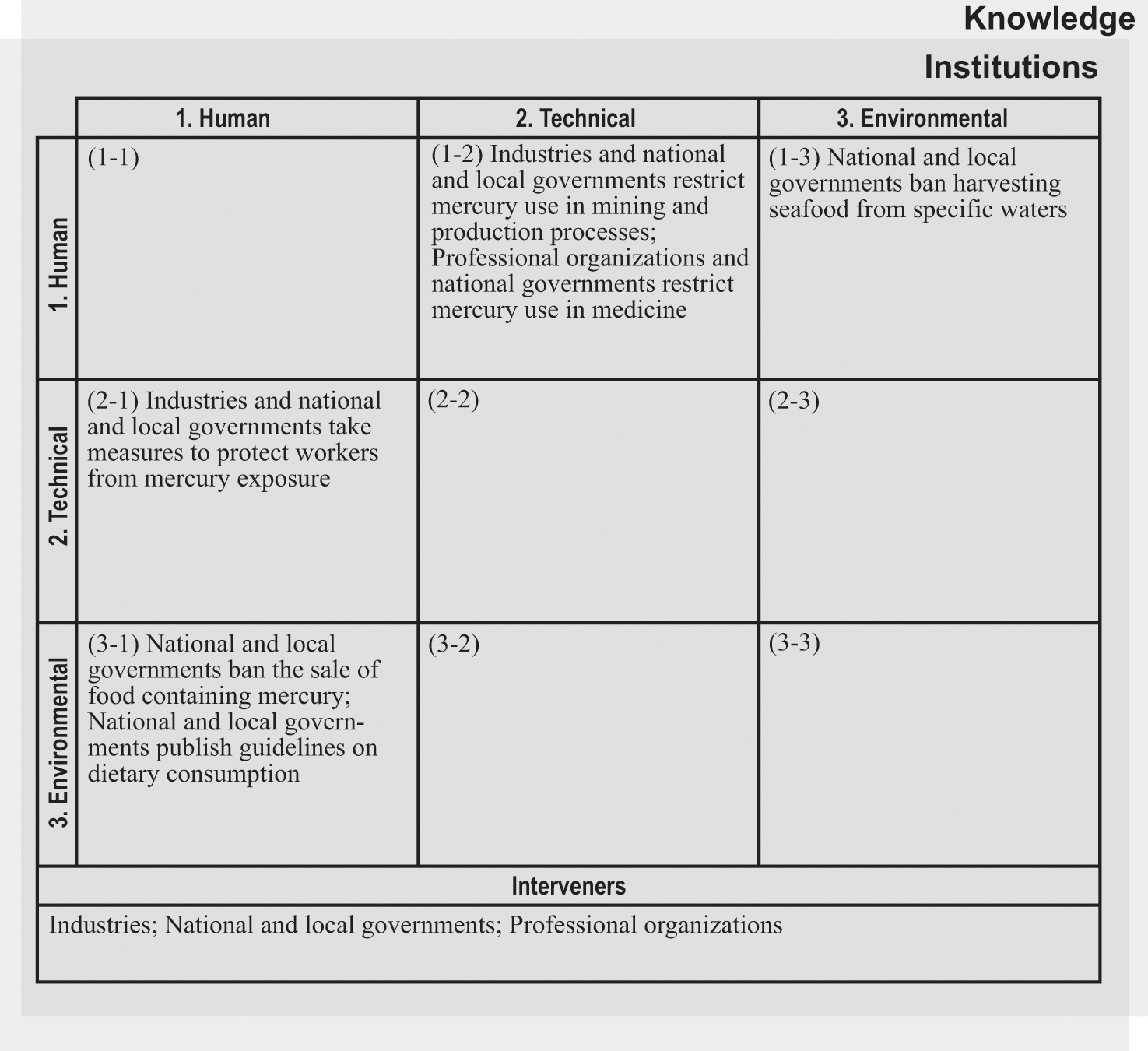

In varying ways, interveners including industries, governments, and professional organizations have aimed to reduce mercury-related health damages and improve human well-being by targeting different routes of mercury exposure. Figure 4.4 identifies key interveners and their efforts to address the human health impacts of mercury. First, we discuss actions to address exposure to elevated levels of mercury in specific locations (boxes 1-2, 2-1, and 1-3). We next examine efforts to restrict mercury use in medicine (box 1-2). We then discuss interventions to mitigate the harms of exposure through dietary consumption, including to lower doses from long-range transport (box 3-1).

Intervention matrix for the mercury and health system.

Addressing Elevated Exposure to Mercury in Specific Places

Industries as well as national and local governments have taken measures to protect workers from mercury exposure (box 2-1). Mining is one major sector of mercury exposure where interventions to reduce health risks have been applied (see chapter 7 on ASGM for a related discussion). Some early human health–related interventions in the mercury mines in Almadén and Idrija focused on prolonging the ability of miners—many who were slaves and convicts, and thus forced into mining—to labor under brutal conditions. These interventions included actions to limit each miner’s exposure to mercury vapor in the underground mining shafts: daily working hours in the mercury mine in Idrija were reduced to six hours in 1665 due to health concerns (Goldwater 1972). Working hours were gradually limited in other mercury mines as well: one system in Almadén counted eight days of four-hour shifts in the mines as equivalent to a month’s work (Hamilton 1943). In addition, the royal miners’ hospital in Almadén opened in 1752, and the first doctor in Idrija was hired in 1754.

Spanish colonial authorities in the early 1600s debated how to address the dangers to indigenous workers in the mercury mine in Huancavelica, and in the silver mine in Potosí in Bolivia. Arguments made for and against action appealed to conscience, on the one hand drawing attention to the moral obligations of protecting indigenous lives (even as they worked as slaves), and on the other hand weighing the loss of those workers as a labor force relative to the benefits of mercury in the silver mining economy (Brown 2001). Spanish authorities closed underground shafts and returned to open pit mining in Huancavelica in 1604 (Robins 2011). The economic benefits of silver production, however, prompted authorities to reintroduce shaft mining just a few years later, trumping any human health concerns about the risks to the forced workers (Brown 2001). Rotations among jobs in the mine area were introduced to prevent workers’ continuous exposure to the most toxic areas underground (Brown 2001). The opening of new tunnels increased the productivity of the mine as well as the ventilation, but only modestly improved the very harsh (and often lethal) conditions for workers, who continued to inhale mercury vapors and other hazardous materials such as silica dust (Robins 2011).

With more workers exposed to mercury and other hazardous substances in manufacturing and industrial production came calls for better worker protections. In the United States, Alice Hamilton played a pioneering role in advocating for workers’ rights in the early twentieth century (Sicherman 1984). Her research was among the earliest in the United States to document many occupational risks, including from mercury (Hamilton 1943). Because of her groundbreaking work, Hamilton became in 1919 the first woman hired to the faculty at Harvard University, where she took up a position in industrial health. Hamilton expanded her work at Harvard to address the risks to workers in mercury mining and mercury-using industries (Hamilton 1943). She visited the mercury mines in New Almaden and New Idrija, and traveled to workplaces that produced mercury lamps and felt hats using a mercury-based technique. The US Post Office issued a 55-cent stamp featuring her image in 1995 in recognition of her contributions to society.

Some of the actions Alice Hamilton and other early advocates called for to protect workers in the manufacturing sectors from mercury exposure were taken by governments long after the occupational dangers of mercury use were first known by health professionals and factory owners. Public authorities, consistent with Minamata Convention provisions, today interact with workers in multiple sectors to develop guidelines for the handling of remaining mercury use, consistent with International Labour Organization (ILO) guidance on occupational exposure. Governments also increasingly require firms that use mercury to put procedures in place for the environmentally safe storage and disposal of excess mercury to prevent human exposure as well as environmental discharges. Scientific laboratories and dental practices in many countries are required, as part of worker safety standards and codes, to ensure good ventilation to protect against mercury vapor, to immediately clean up mercury spills, and to provide appropriate protective clothing such as face masks and rubber gloves.

In some cases, industries and national governments have taken action to restrict mercury use in mining and production processes (box 1-2), and we discuss many of these actions focused on the use of mercury in products and processes in chapter 6. For example, the use of mercury in the hat industry was eventually banned in the United States in 1941 (Goldwater 1972). Some actions included addressing the mining of mercury itself. The phaseout of primary mercury mining helped mitigate much damage to workers’ health. This process included the closings of the world’s two leading mercury mines in Idrija in 1995 and Almadén in 2002, but also mines in Huancavelica in 1974, in Monte Amiata in Italy in 1982, and in the United States and elsewhere during the late twentieth century. The last mercury mine in the US, the McDermitt Mine in Nevada, closed in 1992 (Tepper 2010). Yet many environmental and human health consequences of mercury mining persist. A sign in the municipal museum in Idrija, which is largely dedicated to the city’s mining history, notes: “River Idrijca is still flushing away mercury-laden slime, burdening the environment all the way to the Gulf of Trieste.” Some of this mercury may be converted into methylmercury and continue to cause harm to seafood consumers.

Closed mercury mines are increasingly seen as historical sites, although some mining continues. The two mines at Idrija and Almadén were jointly given World Heritage Site status in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), noting the worldwide importance of mercury extraction to gold and silver mining and to industry, finance, and technology. In 2019, local authorities in China applied for World Heritage Site status for the Wanshan mercury mine, which closed in the early 2000s. Formal mercury mining is ongoing in a few places, including in China and the Kyrgyz Republic, and illegal mining occurs in Indonesia and Mexico. This results in continuing exposure to miners. Because the Minamata Convention allows for existing mercury mining up to 15 years after a country becomes a party, China, as mentioned in chapter 3, plans to continue mercury mining until 2032.

Some national and local government interventions included bans on harvesting seafood from specific waters (box 1-3). The detection of high mercury levels in fish in the Great Lakes region caused both Canadian and American authorities to act in 1970 (Anonymous 1970). The Canadian government first placed an embargo on all fish from Lake St. Clair and the St. Clair River, banning commercial and sport fishing (unless it was for catch and release). Authorities in Michigan and Ohio shortly thereafter also stopped all fishing in Lake St. Clair as well as in the Detroit River and parts of Lake Erie. The need for North American governments to ban the harvesting of seafood because of mercury contamination is not just a thing of the past. In 2014, the Department of Marine Resources in the US state of Maine banned the harvesting of lobster and crab from a seven-square-mile area of the Penobscot River due to elevated mercury levels. The size of the ban area was further expanded in 2016 (Overton 2016).

Lack of scientific knowledge and economic and political interests at times affected responses to mercury pollution, as in the case of Minamata. Researchers at Kumamoto University put together in 1957 a list of 64 possible substances (including mercury) that might cause Minamata disease (George 2001). The researchers, unaware of prior work on organic mercury poisoning, did not pay much attention to mercury initially because they assumed that the factory would not waste such a valuable substance. The British neurologist Douglas McAlpine, however, who visited Kumamoto University in 1958, speculated that the patients’ symptoms were similar to those of methylmercury poisoning, also referred to as Hunter-Russell syndrome. These effects had been described in 1940, and the name Hunter-Russell syndrome came from the 1930s study of workers at the seed packing facility in Norwich, England, who were exposed to methylmercury (Hunter et al. 1940; Rice et al. 2014). Kumamoto researchers paid more attention to organic mercury after McAlpine’s suggestion because of a possible link between Minamata disease and Hunter-Russell syndrome (Takeuchi et al. 1959).

Laboratory experiments by researchers at Kumamoto University showed that methylmercury and ethylmercury produced Minamata disease–like symptoms in cats. One puzzling factor, however, was that the Chisso factory used inorganic (not organic) mercury as a catalyst in its chemicals production. Not until a few years later did the researchers figure out that the inorganic mercury was converted into methylmercury inside the factory during the manufacturing process and then subsequently discharged with the wastewater, something that people at the factory were aware of but hid from the researchers and the public. The finding that methylmercury was discharged from the factory was published in an English-language article in the Kumamoto Medical Journal in 1962, and was picked up by the Japanese media in early 1963 (Irukayama et al. 1962). A former factory manager testified during the trial against Chisso, which started in 1971, that he had already detected a causal connection between the wastewater and the damage to fish around 1954, but that no one took any steps to further investigate the exact cause (George 2001). Instead, Chisso attempted to discredit researchers and resisted regulatory controls.

Phasing Out Medical Uses of Mercury

Professional organizations and national governments have taken measures to restrict mercury use in medicine (box 1-2), yet heated arguments have taken place for centuries over continuing applications. Medical societies in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries opposed mercury-based syphilis treatments (Crosland 2004). These treatments were largely carried out by alchemists, barber-surgeons, and “an array of charlatans” rather than by formally trained doctors (Goldwater 1972, 220). Therapeutic uses of mercurial drugs increased in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and this “resulted in the production of a literature of prodigious proportions” (Goldwater 1972, 244). In an article from 1930, three scientists at Boston City Hospital and the Harvard Medical School noted that mercury and its salts ranked “among the most widely used drugs in medicine” and that their therapeutic value was “well established” (Young et al. 1930, 539). Almost all medical doctors and governments agree today that most mercury uses in medicine should be eliminated, but evidence exists that cinnabar is still included in some traditional medicine, in China for example (Liu et al. 2008).

On some occasions, doctors voluntarily phased out certain medical uses of mercury when they believed that there were better and (sometimes) safer alternatives for treating patients. Many doctors began to use arsenic or bismuth instead of mercury for treating syphilis beginning in the 1910s. Penicillin, a much superior treatment option for syphilis and other illnesses, became the common choice in the medical profession by the 1940s (Svidén and Jonsson 2001). Regulatory interventions by governments drove the phaseout of medical uses of mercury in some cases, especially in the second half of the twentieth century. For example, public authorities in the 1950s began to ban the use of mercury compounds in teething powders to address problems with acrodynia in children (Black 1999). In 1980, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) identified over-the-counter vaginal contraceptives containing phenylmercuric acetate or any other mercury compound as “not generally recognized as safe” to use (US Food and Drug Administration 1980). These were formally removed from the US market in 1998, together with mercurochrome and other mercury-containing topical antimicrobials and diaper disinfectants (US Food and Drug Administration 1998). Phenylmercury compounds have been phased out in eye drops and other antibacterial applications, but some uses continued into the 2010s (Kaur et al. 2009; Ezenobi and Chinaka 2018). Mercurochrome and other mercury-containing antimicrobials were also still in use in some countries outside North America and Europe in the 2010s (Bell et al. 2014). The Minamata Convention mandated the phase out of mercury in topical antiseptics by 2020.

The continuing use of mercury, both in dental amalgams and in vaccines, remains a high-profile issue. A growing number of dentists began to use mercury-containing amalgams in the early nineteenth century, but some who preferred the older gold-based method of filling cavities resisted the change. This led to the “Amalgam War” in the United States in the mid-1800s, as dentists who used mercury-based amalgams were expelled from the American Association of Dental Surgeons. At that time, if affected teeth were not removed, cavities were often filled with gold foil that was “pounded into cavities, a process which was time-consuming and painful” (Goldwater 1972, 279). Use of mercury-containing amalgams increased around the world in the late 1800s with the development of more reliable amalgams. A second round of amalgam-based disputes started in the 1920s when some chemists who were concerned about mercury vapor, including Alfred Stock, argued that mercury amalgam constituted a serious health threat to patients and dentists (Goldwater 1972). Nevertheless, mercury amalgam remained common because of its durability even as other mercury uses were phased out during the twentieth century. Dental amalgam accounted for one third of all mercury use in Sweden, for example, by the late 1990s (Hylander and Meili 2005).

Current scientific evidence does not support the argument that the typically very small amount of mercury vapor inhaled after being released from mercury amalgams is dangerous to patients’ health, except in a very small number of people developing contact allergies (Clarkson and Magos 2006). However, dentists can be highly exposed if they do not take appropriate measures to protect themselves, and mercury waste from dentistry can enter the environment if not properly disposed of. Dental interest groups continue to weigh in on both sides of the debate. Large organizations such as the World Dental Federation and the American Dental Association support the continued use of mercury in some instances. In contrast, smaller groups such as the World Alliance for Mercury Free Dentistry advocate for banning all mercury amalgams (Mackey et al. 2014). A substantial argument against bans is the cost of substitutes, which tend to be more expensive. The World Health Organization (WHO) argues that in low- and middle-income countries, the extra cost could put necessary dental treatment out of reach for people who need it (World Health Organization 2010). Based largely on the WHO’s position that mercury-based amalgam still plays an important role in many parts of the world, the Minamata Convention stipulates a phase-down of dental amalgam use, but without setting a deadline (H. Selin 2014). However, discussions continue, with some parties in favor of taking stronger action under the Minamata Convention on dental amalgam.

Governments in some countries and regions including Europe have taken steps to phase out mercury in dental amalgam to protect the environment as well as for precautionary reasons related to human health. In 2009, Sweden introduced a national ban on mercury in products, but kept an exception for the use of dental amalgam for special medical reasons. This exception was removed in 2018, but dentists can continue to apply for dispensation for dental amalgam on a case-by-case basis (Swedish Chemicals Inspectorate 2017). A European Union (EU) regulation prohibits the use of mercury-based amalgams for vulnerable populations (pregnant or breastfeeding women and children under the age of 15). The EU also mandates the use of pre-dosed encapsulated amalgam and amalgam separators in dental clinics to prevent mercury releases into sewage systems and water bodies. After other mercury uses were phased out, dental amalgam was the largest category of mercury use in the EU by 2018 (European Environment Agency 2018). The European Commission is required in 2020 to report to the European Parliament and the member states in the Council of the European Union on the feasibility of ending all dental amalgam use by 2030 (European Commission 2017b).

The contemporary discourse on mercury in vaccines is similar in focus to debates about the use of dental amalgam: how to appropriately balance clear and important health benefits of specific mercury uses in the medical sector with sensible precautionary actions to protect human health. Specifically, this issue concerns the use of very small amounts of thimerosal as a preservative in vaccines to remove the need for refrigeration. The addition of thimerosal, as noted above, makes it much easier to store, transport, and safely use life-saving vaccines, especially in remote and less populated areas. Ethylmercury, the type of mercury in thimerosal, is different from the other mercury forms, such as methylmercury, that are well known for their toxic effects. As a result, it distributes differently in human tissues and metabolizes at a different rate from methylmercury (Clarkson and Magos 2006). The low levels of ethylmercury that US infants were exposed to through vaccines exceeded health guideline levels set for the different form methylmercury (Baker 2008), but no comparable guideline for ethylmercury exists.

Mercury is intertwined in a growing public discourse about vaccine safety. Vocal parents and advocacy groups surrounding children with autism have influenced public controversies about mercury, which are connected to a discredited but publicly influential study in 1998 by the British gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield. This study, which was retracted in 2010 after it was found to be falsified, linked autism with the measles-mumps-rubella vaccination. It did not specifically focus on mercury, as that vaccine never contained thimerosal. Yet, some US parents who connected the features of autism with those of mercury poisoning published a study alleging a link between thimerosal and autism in the controversial journal Medical Hypotheses (Bernard et al. 2001; Kirby 2006). This publication reflected an organized movement against the use of mercury in vaccines. One example of an advocacy organization focused on this issue is the US-based SafeMinds, created in 2000 to argue that toxic substances (including mercury) play a role in autism. American attorney and environmental activist Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has also repeatedly alleged that mercury in vaccines is poisoning American children, a controversial position sharply rebuked by other members of his famous family (Mnookin 2017; Epstein 2019).

Some medical associations and authorities acted on thimerosal starting in the 1990s. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention proposed in 1999 that despite no conclusive evidence of harm, thimerosal should be removed from vaccines (Baker 2008). This precautionary measure prompted manufacturers to eliminate thimerosal from routine childhood vaccines in the United States by 2001 (Halsey and Goldman 2001), but it also contributed to the continued public debate over the safety of vaccination more generally. Thimerosal is still used in the United States in some common vaccines, including sometimes against influenza. The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products in 1999 recommended that although no evidence exists of harms from thimerosal in vaccines, thimerosal-free vaccines should be used for infants and toddlers based on the precautionary principle (EMEA 1999). In Australia, childhood vaccines have been thimerosal-free since 2000, with the exception of a minute amount in vaccinations against hepatitis B (Australia National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance 2009).

The international debate about the use of thimerosal in vaccines continued in the 2010s. During the negotiations of the Minamata Convention, a group called the Coalition for Mercury-free Drugs argued that allowing continued use of thimerosal reflected a double standard where children in developing countries were not protected by the precautionary principle applied to children in developed countries (Sykes et al. 2014). Yet, eliminating all multi-use vials containing mercury could jeopardize critical public health interventions in developing countries, where vaccine distribution faces challenges because cold storage is not readily available in all areas (Tavernise 2012). In response to arguments about the need for its continued use in global health protection, the use of mercury in vaccines is specifically exempted from requirements on mercury in products under the Minamata Convention. This decision was in large part influenced by the continued support for the use of thimerosal in multi-dose vaccines by the WHO, GAVI (The Vaccine Alliance), and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), three organizations that collectively argued strongly against a ban (GAVI 2012; Earth Negotiations Bulletin 2013a; Vaccine News Net 2013).

Addressing Exposure through Dietary Consumption

National and local government interventions that addressed dietary mercury exposure included bans on the sale of food containing mercury, including fish (box 3-1). Fish bans began in the 1960s, but food-focused interventions addressing mercury go back to at least 1938, when the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare set a “zero” tolerance for mercurial pesticide residues in food (Goldwater 1972). The Swedish Medical Board in 1967 halted the sale of fish from 40 lakes and rivers due to high levels of methylmercury, and warned that people should moderate their consumption of freshwater fish (Barnes 1967). The US FDA in 1969 set an action level for banning the sale of fish that contained more than 0.5 ppm mercury. In 1970, the FDA removed tuna and later swordfish from the market because of mercury contamination (Mazur 2004; Bell 2019). A lawsuit by swordfish distributors challenged the limit, arguing that mercury was naturally occurring in fish and should not be seen as a contaminant (US Court of Appeals 1980). Partly as a result of industry pressure, the FDA raised the limit to 1 ppm in 1979. The FDA stopped routine testing for mercury in 1998, though many fish on the US market exceeded 1 ppm (Braile 2000). The EU maximum safe limit for mercury is 0.5 ppm for most fish species, but concentrations of 1 ppm are allowed for select species, including swordfish, tuna, and shark (European Union 2006).

National and local governments have recently focused on publishing guidelines on dietary consumption (box 3-1). These guidelines are issued either as a complement to or as a replacement for setting allowable concentrations of mercury in commercial seafood. The WHO develops guidance on balancing the risks and benefits of fish consumption, together with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (FAO/WHO 2011). Domestic dietary guidelines also weigh the risks of methylmercury against the health benefits and cultural importance of seafood consumption. Many national authorities in Europe have issued varying dietary guidelines to minimize methylmercury exposure. In the United Kingdom, pregnant women and children under 16 are advised to avoid eating shark, marlin, and swordfish, and minimize consumption of tuna to four medium-sized cans or two steaks per week (European Environment Agency 2018). Swedish authorities recommend that pregnant or nursing women avoid eating high-mercury fish more than two or three times a year (Sweden National Food Agency 2019). In France, pregnant and breastfeeding women are cautioned to limit their consumption to one portion (defined as 150 grams) per week of fish likely to contain high levels of methylmercury, including tuna, sea bream, halibut, and monkfish (French Agency for Food 2016).

Authorities set dietary guidelines using a process that combines information on methylmercury concentrations in fish, fish consumption, and body weight. A person’s intake of methylmercury is calculated by multiplying the concentration of mercury in food by the total intake of mercury-containing food, and dividing that number by body weight. A concentration of 1 ppm is equal to 1 microgram of methylmercury per gram of food. If a person who weighs 50 kilograms (110 pounds) eats 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of fish with a concentration of 1 ppm, it would result in a dose of 2 micrograms of methylmercury per kilogram of body weight. This individual methylmercury dose can then be compared to a reference dose: an amount derived by calculating the lowest level at which effects are observed in epidemiological studies and then reducing that level for safety to account for variability among exposed individuals. The US National Research Council in 2000, using epidemiological data from the Faroe Islands study, set a reference dose at 0.1 microgram of methylmercury per kilogram body weight per day (US National Research Council 2000). This equals 0.7 micrograms per week. The meal described above would exceed this guideline. Some researchers argue that this reference dose should be halved based on more recent data on the dangers of methylmercury (Grandjean and Budtz-Jørgensen 2007; Grandjean 2016). The existing US level, however, is lower than some international guidelines. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives in 2003 set its estimate of a provisional tolerable weekly intake of methylmercury to 1.6 micrograms per kilogram for childbearing women.

The US FDA and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2017 agreed on coordinated advice for pregnant women and children; the advice highlights which fish are “best choices,” “good choices,” or “choices to avoid” based on the differences in methylmercury levels between species. Some US states also formulate their own recommendations on the consumption of fish from local waters that contain elevated levels of methylmercury. The 2017 guidelines were the latest revisions of federal-level voluntary guidelines; previous versions met much opposition from the private sector. In the mid-2000s, the tuna industry lobbied the FDA to exclude canned tuna from dietary guidelines, and funded a $25 million campaign to make the case for the benefits of eating fish. The industry’s efforts included placing newspaper ads targeting the public, and funding scientific work at the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis that questioned the relative importance of mercury risks. In a related effort echoing others that have questioned risk-based government policies, the Center for Government Freedom, a nonprofit organization founded by the tobacco industry, created a website to argue that standards for mercury in food were unwarranted (Mencimer 2008).

Well-intended efforts to implement sound dietary advice can have unintended consequences. A study in the United States found that a 2001 federal advisory on mercury content in fish resulted in an overall decline in total fish consumption by pregnant women (Oken et al. 2003), but consuming fish during pregnancy can have important nutritional benefits. To minimize potential unintended consequences, today’s communication on the risks of methylmercury consumption for pregnant women and children emphasizes balancing the benefits and risks of fish consumption. People are encouraged to eat fish low in mercury to maximize positive benefits and minimize negative impacts. A point made by Pál Weihe, a local physician and researcher who worked on many of the Faroe Islands studies, sums up the importance of dietary choice: “For every portion of whale you could eat 100 portions of cod” (Fielding 2010, 436). More recent dietary advice also acknowledges the complexity and variability of risk, including approaches to protect sensitive populations. Emerging scientific knowledge about the genetic markers that influence a person’s sensitivity to mercury may be used in the future to better identify susceptible subpopulations, and thus guide intervention efforts (Basu et al. 2014).

Insights

The Minamata pollution story that opened this chapter captures the dangers to human health that mercury and mercury compounds pose, as well as the societal struggles to effectively address them. In this section, we draw insights from the multiple ways that mercury has affected human health. First, the dangers that mercury poses are determined by its inherent properties as a hazardous substance as well as its interactions with technology and society. Second, understanding and implementing transitions toward greater human well-being relate to how harms from mercury to human health are valued, and transitions focused on enhancing human health protection have largely been incremental to date. Third, governance to protect human health from mercury involves integrating risk reduction strategies at levels from local to global, using various types of interventions.

Systems Analysis for Sustainability

Understanding how people are harmed by mercury requires examining the ways in which people’s exposure to differing forms and amounts of mercury is influenced by technologies, knowledge, institutions, and environmental processes. Interactions between workers and employers, for instance, led to changes in working conditions that affected mercury use and exposure. In some cases, technological change, such as increased ventilation in mines and workplaces and the use of protective equipment, lowered people’s exposure to mercury. In other cases, the use of scientific and technical knowledge about mercury’s properties to develop new mercury-based products and manufacturing processes increased the number of workers who came in contact with mercury. But as knowledge of mercury’s toxic properties and techniques for health protection improved, local exposure to mercury in laboratories and other workplaces decreased. The dispersal of mercury through the environment, however, connects sources of mercury to health impacts in remote locations. Environmental processes transform mercury into methylmercury, which contaminates fish; dietary choices to eat or not eat certain species of fish influence people’s intake of methylmercury; and dietary recommendations from governments or agencies can influence these consumption choices.

The mercury health system has shown a resistance to change over time, even though continuing mercury use has largely resulted in harms to human well-being. Mercury mining, and uses of mercury in silver and gold mining, other workplaces, and in medicine, continued for centuries despite much evidence of health dangers. The environment responds slowly to changes in discharges, and people (and other organisms) are not able to biologically adapt to higher exposures to mercury. Some resistance to change, however, can be seen as beneficial to human health. The WHO and many dentists and doctors oppose calls for immediate bans on the use of mercury, both in dentistry and vaccines, on the grounds that such measures would end up harming human well-being. However, some adaptations, like dietary changes, can have short-term health benefits by reducing methylmercury exposure. All such changes are more supportive of human health when implemented carefully, as less-informed changes can be detrimental. This was the case when pregnant women ate less fish because of methylmercury advisories, thereby forgoing nutritional benefits from eating fish.