8

There It Is

JERRY MCCAULEY STRANGLED an enemy soldier with the chinstrap of his helmet. He managed to step aside and avoid the man’s bayonet thrust and then grabbed his helmet, which was strapped under the chin, and, with a tremendous surge of adrenaline, twisted the strap violently around his neck, held him down, and choked him to death. It took an agonizingly long time to do. Afterward he hardly gave it a second thought. It had been a life-and-death struggle, and if he felt anything, it was amazement that he’d had the strength and presence of mind to prevail. Not all of his kills left him that untroubled.

After the tower was taken, McCauley helped stand guard. It had been reduced to four tall heaps of charred brick and mortar, but it was still the highest point on the east wall. His machine-gun squad, part of Alpha Company, would creep up after dark and choose a new position every night at about ten o’clock. There were still enemy guns close enough to mortar them if they were discovered. They usually settled into existing spider holes, one dug by the Front before the marines arrived, or in between large chunks of what had been the tower. The wall below had crumbled, so the Dong Ba Gate was now impassable to vehicles. People, however, could still slip through.

The view from McCauley’s position was panoramic. The falling flares sketched the city in tones from silver gray to black. Roofs and walls had crumbled into piles of wood lathing, plaster, tile, and stone. Some of the outer walls still stood with empty black windows and doorways that opened on littered hollows. Here and there were shattered bamboo gardens with jumbled piles of scorched stems that looked like discarded pipes. In the middle of the night the ruins became spookily silent. There was the occasional pop of a rifle, but men on both lines did their best to stay still and quiet, so close to each other that it wasn’t safe to reveal exactly where they were. Sometimes enemy mortars would rise from outside the Citadel, arc over the walls, and crash into the neighborhoods inside. They were anything but precise. Some would explode against the wall; some skipped off the top and landed by pure chance inside, as likely to hit the Front’s own lines as marines. There was never a minute when death could not arrive without warning. McCauley spent those hours behind an M60 machine gun. They had strict orders to shoot anything or anyone—even any Americans—who tried to pass through the ruined gate.

“Anyone who tries to come through, you are to consider them the enemy,” they were instructed. “You are to shoot and kill them.”

There was cause to be suspicious of everything, and also to shoot without warning. Calling out gave away your position. And anyone exiting the fortress could be delivering useful intelligence to those mortar batteries outside.

But there were also civilians still trying to escape. Those in the killing zone faced a maze of gun positions, manned by fighters on both sides, all of them jumpy. One night up on the wall, McCauley and his assistant gunner spotted what looked like a Vietnamese couple with two children approaching the gate on the street below. It was two o’clock in the morning. The squad hesitated.

“Our orders are to kill them,” one of the men said.

They went back and forth about it, and one of the men said, “You have the gun, McCauley, you do it.”

He shot them down. He was relieved to learn later that the woman had a carefully drawn map of where the gun positions were on the streets leading to the gate. McCauley took that as confirmation that the couple were delivering intelligence, so he felt better about killing them. The map, of course, was also exactly what people would make before trying to pick their way out of a dangerous spot.

Chris Jenkins, the International Voluntary Services (IVS) worker from Philadelphia who had been hiding in a house just south of the tower ever since the first night of Tet, got back under his bed when his Vietnamese friends heard firing close by. Then someone knocked on the door.

An American voice shouted, “Are there any VC in there?”

Jenkins got up and identified himself. It was one of Thompson’s marines.

“You’re lucky we didn’t throw a grenade in the window before asking questions,” he said.

He was escorted to Captain Jennings, who asked with disbelief, “Did the marine really walk up and ask, ‘Are there any VC in there?’”

Jenkins nodded.

“It’s a great war,” said Jennings.49

The battle sputtered to a near halt again on Friday, February 16. After taking the tower, Thompson’s battalion had nine blocks between it and the fortress’s south wall. General Truong’s troops, which would soon be heavily reinforced, had about the same distance to cover on the west side. That would leave only the royal palace, which they knew was now the command center for Front troops inside the Citadel. With the triangle now almost fully recovered, if the army could do its job in the countryside to the west and north, the battle would at last be over.

Alvin Webb, the veteran United Press International (UPI) war reporter, wrote a personal account on Saturday, from the front lines inside the Citadel:

This is getting tough and terrifying. I don’t mind admitting I’m scared. I wish we knew what was going on on the outside. It is nine blocks from where I am sitting on the south side of the wall around the Citadel.

It may become the bloodiest nine blocks for the men of the U.S. Marine Corps since that other war in Korea when they fought and died in the streets of Seoul.

“Seoul was tough,” an old top sergeant who was there told me a few minutes ago. “But this—well, it’s something else.”

There is a kid marine on a stretcher about 10 feet from me. There isn’t much left of his left leg.

. . . “Five snipers,” Capt. Scott Nelson of Jacksonville, Fla., said. “That’s all it takes to tie us down completely.”

You can hear the whine of the snipers’ bullets and the eerie whoosh of B-40 rockets and feel the thunder of mortar rounds chewing up houses.

“This all looks terrible,” Cpl. Frank Lundy of Gravette, Ark., said. “We’re being eaten up. They gotta get out of here.”50

Progress was painfully slow. The big guns on the tanks and the Ontos and the skill of the marine artillery batteries had made progress inevitable—the marines could now batter enemy positions mercilessly before attempting to cross streets. Artillery would unload first, and then, following the pattern Cheatham had developed across the river, the tanks would roll out, drawing fire from every quarter. This would reveal the major enemy gun positions. Then the Ontos would race out in front and unload with all six barrels before scooting back to cover. The tactics worked by destroying everything in the marines’ path. The Front retreated to ever-shrinking ground.

Michael Herr, the Esquire writer, described Major Thompson at his command headquarters, just a few blocks behind the forward line:

At night in the CP [Command Post], the major who commanded the battalion would sit reading his maps, staring vacantly at the trapezoid of the Citadel. It could have been a scene in a Norman farmhouse twenty-five years ago, with candles burning on the tables, bottles of red wine arranged along damaged shelves, the chill in the room, the high ceilings, the heavy ornate cross on the wall. The major had not slept for five nights, and for the fifth night in a row he assured us that tomorrow would get it for sure, the final stretch of wall would be taken and he had all the marines he needed to do it. And one of his aides, a tough mustang first lieutenant, would pitch a hard, ironic smile above the major’s stare, a smile that rejected good news, it was like hearing him say, “The major here is full of shit, and we both know it.”51

The enemy was tenacious. The marines paid for every block, sometimes for every house. On one of these days, Calvin Hart, the marine who had volunteered for Vietnam in hopes of becoming a military policeman, faced a wrenching dilemma. Doc Rhino—Michael Reinhold—one of the platoon corpsmen, a man whose selfless acts of courage under fire had made him revered, finally tempted fate once too often. He was shot down as he ran from cover to reach two downed men. Reinhold was a tall, red-haired man from Arizona, a big target anyway, and he had gotten himself an army backpack that was twice the size of the ones issued to marines just so he could carry more medical supplies. The guys loved him. And now he was down in the open. He got up on one knee and was trying to pull himself upright when he was shot again. This time he lay motionless, clearly dead. He stayed there until dark, about twenty-five feet in front of them. A platoon sergeant then asked for volunteers to go out and bring Doc and the others back.

Hart desperately did not want to volunteer. It was a rule he’d embraced in boot camp that had been strongly reinforced by experience—never volunteer for anything. But on the other hand, he wanted to do the decent thing. If he were out there, he sure as hell would want somebody to come get him. Not raising his hand was a moral failure that he knew would haunt him. Why should somebody else have to do it? He was new. He had taken nowhere near the same number of risks these other men had. How could he not volunteer? It was quiet, but they had all learned during the day that the enemy was dug in all around. The sergeant’s challenge hung there for a long, excruciating moment. Hart kept his hand down and was grateful when three others raised theirs. As they prepared to go out, he waited behind his gun for all hell to break loose again and prayed that it would not. All hell did break loose, and Hart fired back with everybody else. Doc Rhino and the other two dead marines were dragged to cover without any of the volunteers getting hit, which was an enormous relief. Hart knew he would not have wanted to carry that around with him.

He was horrified from the first moment he entered Hue to the last. The things he saw! The Front’s snipers were extremely accurate, and they aimed for the head. Guys would be sitting on the floor and not even realize that the tops of their heads were visible through the window, and the next second they were dead and the tops of their heads were gone. One marine was hit in the head and toppled out of a second-floor window, except his foot was tangled on something so he hung upside down while the inside of his skull emptied. There was this one dead Vietnamese woman in the street. Both of her legs had been crushed flat by a tank. When Hart’s squad walked past her the first time, she was sitting upright, dead, with a surprised look. When they came back that way she had been run over so many times that you could no longer even tell she had been a person.

“There it is,” said one of the men in his squad. It was a sentence they nearly wore out.

Hart had come to Vietnam expecting to fight amateurs, little men in black pajamas and conical hats who were no match for United States Marines. But the enemy encountered in Hue was tough and professional, every bit their match. These fighters were uniformed and well-equipped, and they set up defensive positions and fields of fire as good as anything taught by the Corps. And they sure as hell seemed to believe in their cause. In his first few days Hart had seen some dragged live from spider holes where they had stayed behind to fight to the death. As tough as the marines were, they didn’t feel that kind of commitment. He and the other grunts, as far as Hart was concerned, at least half of them, had no clear idea why they were even there. None of them knew enough to write a paragraph about Vietnam. Maybe the officers did, but most of the grunts, it seemed to him, didn’t even really care to know more. They had enlisted, they were trained to fight, the country had sent them. Enough said. As far as Hart could see it, they fought mostly to finish out their tours and get their asses home intact. That was it. Still, there were situations like Doc Rhino’s that seemed to demand something heroic, even from him.

Who lived and who didn’t live, who got hurt and who seemed immune . . . it made no sense. Every day some of the smartest, most salty guys got hit, and others, well . . . take Leflar. He’d been in trouble since the day they came. The first days in particular, Leflar had seemed almost comically lost. But other than those scratches he kept whining about, the kid seemed invincible. In the middle of one grinding street battle a Patton clanked out into the street and slowly turned and then raised its big gun to aim at a house on the edge of their line. Hart knew that Leflar was upstairs on its second floor. And just as the realization hit—BOOM!—the gun blasted away half of the building. Hart and the rest of his squad found Leflar in the rubble, coated with pulverized mortar and dust but otherwise unharmed. A squared-away guy like Doc Rhino was dead, and Leflar? He seemed to have nine lives!

Captain Harrington’s company fought down the top of the wall in tandem with the marines advancing on the streets below. Harrington was surprised that the Front did not launch any counterattacks. With the pressure being put on the southwest sector, they could not have been getting much ammo or replacements anymore. The killing of the Front’s regimental commander in the artillery barrage had apparently created some confusion. But the fight didn’t get easier.

Webb, moving with Harrington’s men, wrote:

I am alive and intact, for the moment. But when I look around me I get the sinking feeling I am among a rapidly diminishing number of Americans in Hue who can say that.

The monsoon drizzle woke us this morning. It fell gently, making little puddles. There was a warming fire and the leathernecks sat around chatting in the wet gray dawn.

A marine stepped briskly into the circle. “Charlie is getting resupplied. They just advised us.”

He was followed by another, “Okay. Saddle up. We’re moving out.”

We moved out . . . We are in Finh Street.

On our right, Bravo and Charlie companies had pulled even with us.

“Let’s go!” somebody screamed.

The sky was suddenly filled with lead, steel, and explosions from both directions. [Greg] Jenkins was not with us this morning. The platoon leader lost some fingers on his right hand on Saturday. He will have a Purple Heart to go with his Silver Star. Neither was [John] Carlson here today. A concussion from a communist grenade had blown his ear drums.

A lot of others are not here this morning either. They were men whose faces I had come to know well. Their bleeding and dying in this war is over.

We went terrace by terrace . . . I timed my moves between rockets and dashed across the street and up a flight of broken stairs over a 2 ft high stretch of barbed wire. Bullets sang over my head.52

When the marines got to within four hundred yards of the south wall, the enemy was about as compressed and dug-in as it could be. That day marines found two dead enemy fighters chained to their heavy machine guns.53 Fred Emery, a reporter for the Times of London, was shown the bodies and the chains. It was the only instance of its kind, and the men may have been prisoners released weeks earlier and forced to fight, but the story quickly made the rounds, reinforcing the notion that the enemy was made up of soldiers who would fight to the last, not because they believed in their cause but because they were being compelled to do so.

Firepower made all the difference. When it could, the air force now dropped napalm over neighborhoods still occupied by the enemy. It was more effective than bombs, which left piles of rubble into which the enemy could crawl and set up new firing positions. With napalm, the flames sucked all of the oxygen out of underground bunkers, suffocating anyone inside, while incinerating everything above that wasn’t made of stone. There was no ducking the onslaught.

And Harrington was right about resupply. By the third week of the siege the Front was depleted of both men and ammo. It could not compete with the marines’ ceaseless reserves of guns and bombs and men. Le Huu Tong, the bazooka gunner, had seen seven members of his squad killed by one tank round. Their bodies were torn into pieces and scattered so badly that his squad could not bury the men individually. His squad especially feared the Ontos. It came close and its aim was more precise. It could kill men hiding behind thick stone walls. During daylight they now spent as much of their time moving as fighting, saving their ammo, picking their shots.54 The Front’s tactics impressed the veteran marine officers. Under terrible conditions it maintained order and was still conducting disciplined maneuvers.

Grunts who had been eager for combat were sorely disabused. The conditions were hellish. Tommy Brown, who arrived a day or two after Leflar and Hart, joining Harrington’s company, had been so eager to get to Vietnam that when he was told it might be months before he shipped out he went AWOL out of disgust. He got caught six months later and spent a month in the brig before they gave him what he wanted.

Brown was now bewildered and revolted by what he’d sought. He spent the first night in Hue scared, damp, and cold, listening to the gunfire in the distance. His squad leader kept moving them. They would settle into a building, doze off, and an hour later be roused to move someplace else. But once the sun came up he relaxed, followed orders, and felt safer, surrounded by ruins that reminded him of photographs he had seen of European cities during World War II. They moved amid the detritus of everyday lives, vitamin bottles, a child’s backpack filled with homework smeared with blood, American candy bar wrappers, the contents of someone’s shattered wardrobe. It was nothing at all like what Brown expected—the Corps had prepared him for Vietnam by giving a course in jungle fighting. The city itself, the parts of it still standing, reminded him of Nashville, where he had grown up. He was struck by the images of the swastika he saw everywhere, not knowing that it was an ancient Buddhist sign for good fortune (and not noticing that it was an inverted form of the Nazi symbol).55 There were cars and trucks everywhere. The tops of the trees were nearly all blown away.

One of the first buildings Brown entered was a spaghetti factory. It had been blown up and everything inside was draped with strings of pasta. One of his squad mates exclaimed, “Mamma mia!” The factory was infested with rats. Another night they camped out at an abandoned Esso gas station.

All of this was just strange. What really shook Brown was the unremitting horror and cruelty. He watched as an enemy soldier who refused to come out of a spider hole voluntarily was blown out of it in pieces. In one very big, well-appointed house they found two dead children who had not been killed in an explosion; each had been shot multiple times. Who would be deliberately shooting kids?

“There it is,” one of the men said.

Dogs were shot by reflex—after you’d seen one rooting into a dead body it wasn’t hard to do. Brown watched a tank run over a big hog, which got caught up in the treads and carried along a distance before it fell out, its remains completely flattened by the tank behind it. People were run over, too, civilians mostly. He was walking behind Harrington and his squad leader, Sergeant Richard Morris, when they came upon a dead enemy soldier whom rigor mortis had frozen with one arm pointing up. Morris walked over to the body and kicked it, then turned to Harrington and said, “He won’t talk, sir.” Brown thought it was funny but the captain did not.

Every night there was booze. Bottles discovered in empty houses were opened and shared. Brown was just eighteen and had little experience with alcohol. Whenever they moved a few blocks behind each day’s firing line, there were children peddling beer in sixteen-ounce bottles. The men had been drinking brackish well water dosed with iodine pills or Kool-Aid packets they received in letters from home, mixing it in their canteens to cover up the bad taste, so even warm beer looked good. Brown discovered the wretchedness of a hangover. He saw marines looting; one ran out of a jewelry store with watches up his forearms to the elbow. Later, when the fighting inside the Citadel was over, Major Thompson declared that any object for which a marine had no proof of purchase would be destroyed. Men started smashing radios and watches and other loot against the walls, much to the dismay of Vietnamese civilians looking on.

Rick Grissinger came to Hue on the same day as Brown. A small, skinny eighteen-year-old from Clearwater, Florida, Rick was a religious young man who didn’t drink, smoke, or swear. He’d been eager to come to Vietnam, but the war turned out to be a lot different from what he’d imagined. He was repulsed by the bodies floating in the Huong River. He reeled at a stack of partly burned Vietnamese bodies, soldiers and civilians. Someone had doused them with diesel fuel and set them on fire, but the effort had just left them charred. In the pile were also body parts. He could not sleep. An older sergeant, a large black man, took him into a bombed-out house on his first day and showed him a Vietnamese family, man and woman and children, all dead. They had been wired together before being shot and set on fire.

“I know what you learned in high school, but this is what Communism really is,” the sergeant said.

He watched bulldozers moving great piles of bodies into mass graves. The stench was so horrible, his stomach would turn just thinking about it years later.

“There it is,” he said.

On every block they found people hiding in holes. The marines were amazed that people could survive crowded together underground in spaces so small. In one, they found ten family members who said they had been there for two or three days. The family emerged screaming, terrified, with their hands over their heads. The marines checked them for weapons and sent them to the throngs now being managed by Truong’s forces.

It had become an enormous job. In order to avoid being infiltrated by the enemy, Truong’s men had to question every civilian. Those deemed true civilians were herded into several school buildings where they camped. Those deemed prisoners were bound and roped together. They sat squatting on their haunches, blindfolded or with their heads covered by burlap sacks, silent and stoical, waiting to be carried off by choppers to an uncertain fate. Some of the ARVN soldiers abused them, spitting on them, slapping them, kicking them, or poking at them with rifles.

Surrendering could get you killed. Felix Bolo, the Agence France-Presse bureau chief, described a scene he witnessed:

Hue. Feb. 21—He was waving a white flag, but it did not stop the bullets.

I watched him today, one of four civilians who emerged from houses burning after a napalm attack by United States Skyhawk fighter-bombers. The houses were in the bullet-riddled Sporting Club zone between two American positions.

One of the civilians ran to hide but the other three walked slowly, waving what appeared to be a white flag. From the United States marine sector came a hail of fire. Two of the civilians dived for shelter. The third stopped short at the top of some stone steps, turned slowly around, dropped the flag, and collapsed. He did not get up again.

Some 150 Vietnamese refugees, including 50 terrified children, hiding in the Sporting Club cellar watched through the cellar windows. “How sad. It was a civilian,” one of the refugees commented to me.

The Skyhawk attack was the first time since Friday that aircraft had intervened in the battle of Hue. The Skyhawks dropped bombs and napalm on the Citadel a few yards away from the Imperial Palace where the Vietcong flag continues to wave. Because of the bad weather the bombs hit a rocket dump from which enormous blue and green flames shot up.56

Washington Post reporter Lee Lescaze was with a group of Bravo Company marines as they camped in an affluent home. There was a Buddhist altar on one side of the first-floor living room, and on the other wall were Playboy centerfolds.

“He’s the Hugh Hefner of Vietnam,” one marine said, settling into an armchair.

They had found a full liquor cabinet and beer, much of which was gone the following morning when some of the owner’s servants came by. The civilians, eager to reoccupy their homes, seemed to know as soon as the marines had cleared them. These servants brought a note, in English, from the house’s owner.

“Let us take back my things and come back to the safe region,” it read. “Thank you very much. We wish you a happy new year and a complete victory.”

“The note said that rice and salt and other ‘precious things’ were to be salvaged,” Lescaze wrote. “Bravo company watched as the servants carried out the television set first, then the refrigerator, then several lamps, plates, and small decorations, then the radio, phonograph and finally a one hundred pound bag of rice. It took four of them three trips before they were finished. They took the Johnny Walker, but the Seagram’s bottle had been broken and the Marines had taken care of the beer.”57

The chaplain, Father McGonigal, failed to show up at Thompson’s quarters Saturday night, February 17. He had been all over the battlefield those first days, heedless of risk, rushing out to help carry the wounded, comforting them, and giving last rites to the dead. Marines in the worst of the fighting would find him at their shoulder, encouraging them. It was heroic, but also, Thompson thought, suicidal.58 The priest stayed with Thompson every night, and they talked.

“Chaplain, you’d better stay back a little bit,” Thompson advised him. “You’re going to get killed.”

When he failed to show up, there was a search. He was found alone in a building near that day’s front line with a hole in the back of his head. A bullet or a piece of shrapnel had found him.

Nineteen-year-old Donny Neveling was put in charge of a ten-man squad when his lieutenant, Moe Green, was shot in the neck. He was proud but quickly learned that with status came responsibility. When a small pig wandered into their camp one afternoon and his men attacked it with bayonets, for fun, the butchery was witnessed by a disgusted battalion master sergeant, who bellowed, “Who’s in charge here!” Neveling, who had dozed off, poked his head out of a window and said, “I am, Lance Corporal Neveling.”

He was summoned that night by Captain Harrington, who chewed him out royally and fined him twenty-five dollars.

The marine Whitmer found in the body bag at Phu Bai, Dennis Michael, had been with Berntson when he died. The combat correspondent had interviewed him days earlier about the second and final assault on the tower. The twenty-year-old private from Vacaville, California, described sitting in a hole with another marine when two ChiCom grenades landed between them. One had rolled off his leg. They had piled out in a panic, but both grenades were duds.

“They’re lousy grenades,” Michael told him. “A lot of times they don’t go off. But when they do, they’ll kill you.”

On Monday, February 19, Berntson was running down the street with a platoon of marines, helping with cover fire, pushing farther down the east wall, when Michael, who was on top of the wall, was shot through the throat. Berntson heard a corpsman calling for help, and ran up the stile to find him kneeling by Michael, who was choking and gasping for air. Rounds were chipping stone around them and kicking up clots of dirt.

“We’ve got to get him down off this wall,” the corpsman said.

They lifted Michael and were trying to carry him down the narrow stairs to the street, when three civilian correspondents, Webb, Charlie Mohr, and Dave Greenway (who had returned to the city after leaving with Roberts), came running. The five of them ran with Michael to a truck that had been blown over on its side and set him down behind it. The corpsman began to perform an emergency tracheotomy. Michael was still choking and gasping. There was lots of blood.

Berntson stood. He saw a wooden shutter blown off a tall window that might work as a stretcher, announced he was going to fetch it, and . . . woke up with ringing ears flat on his back several yards away smelling cordite and burned flesh. Then he felt a searing pain in his arms and back. He tried to get up, but his legs wouldn’t move. The taste of blood was in his mouth. He looked down and saw a large piece of shrapnel projecting from his right arm. The corpsman and the correspondents were still back beside the truck, and Berntson screamed, “For God’s sake, get me off the street before they shoot me!”

He was pulled back to cover. The corpsman must have given him a serious shot of morphine, because the next thing Berntson knew he was at the battalion aid station at Mang Ca, flat on his back in the cold drizzle surrounded by other wounded men. One of his arms was badly mangled. The other was strapped down and connected to an IV tube. He could move neither. He felt stoned, spacey from the morphine. Around him was a world of misery and death, marines groaning and crying in pain, some dying, some already dead. There were not enough body bags for the dead, so doctors would pull the poncho up and over the head of those who expired, and they would be carried off to the dead pile. Every once in a while a gust of wind from a helicopter rotor would blow the ponchos up and their pale, vacant faces would stare across the tarmac.

Michael was near Berntson at the LZ, still alive but dying. He wasn’t going to be evacuated. Triage had sorted him; there were too many others badly wounded with a better chance of making it. The man alongside Berntson already had his face covered.

When a gust of wind blew his poncho up and over his own face, he panicked. He could not move his arms to pull it off. One of the surgeons nearby was complaining bitterly that there were badly wounded Vietnamese soldiers being left to die because his orders were to tend to Americans first. Berntson called to him pitifully, “Captain, don’t let them put me on the dead pile!”

Greenway and Webb were also wounded in the blast.59 They rode back to Phu Bai with Berntson, the Storyteller, in a helicopter.

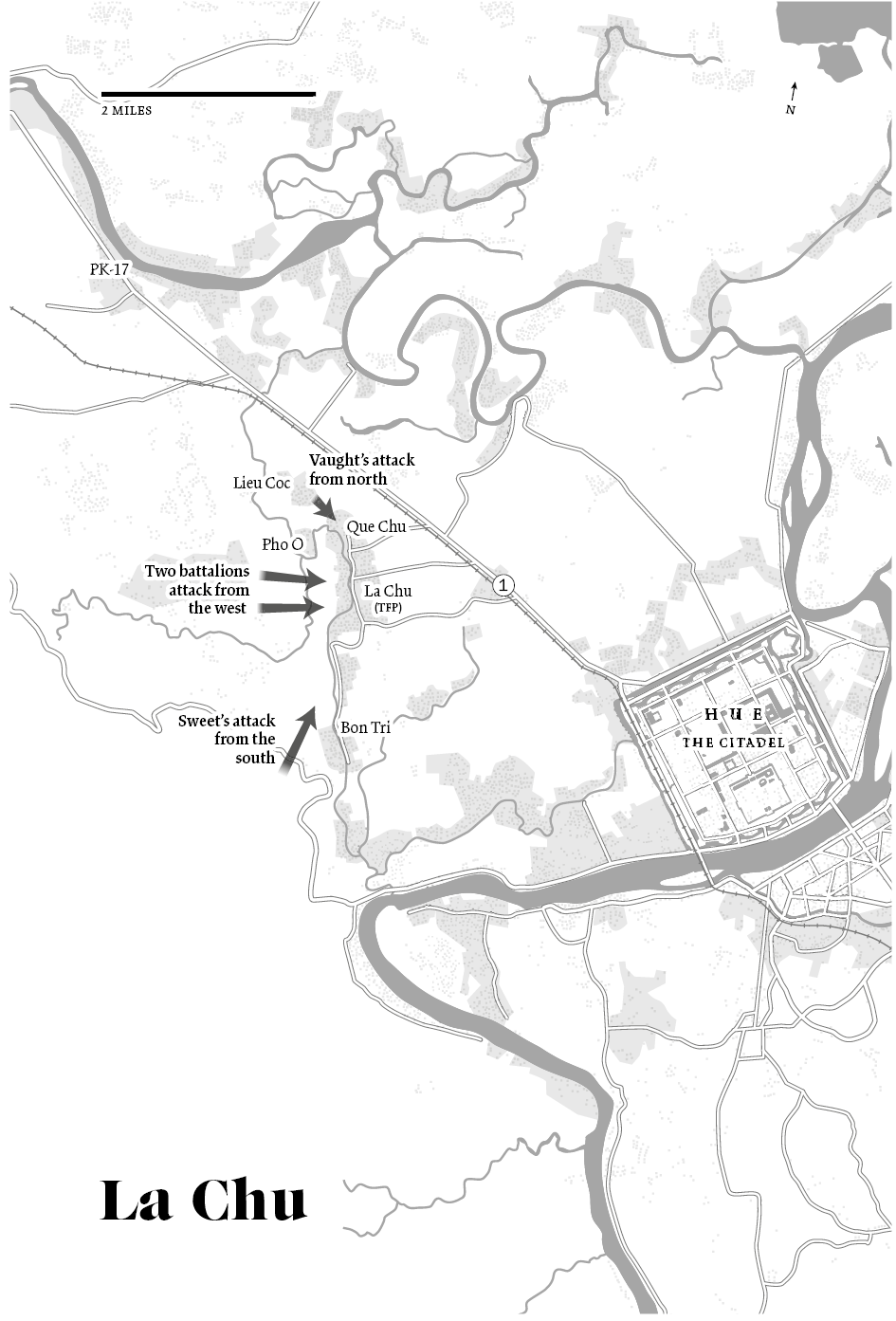

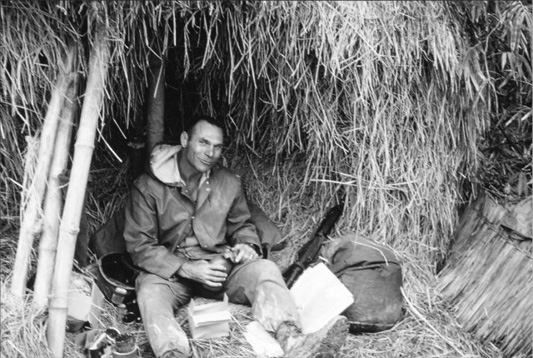

Army Colonel James Vaught on the road to La Chu,

where he would lead the final assault on the Front’s command center.

John Olson’s photo of marines wounded in the Citadel. In the foreground,

shirtless, is Alvin Bert Grantham, who had been shot through the chest.