13

EMPTINESS AND DEPENDENT ARISING

102

If I do this, the enemy will be vanquished!

If I do this, false conceptions will be vanquished!

I will meditate on the nonconceptual wisdom of selflessness.

So why would I not attain the causes and effects of the form body?

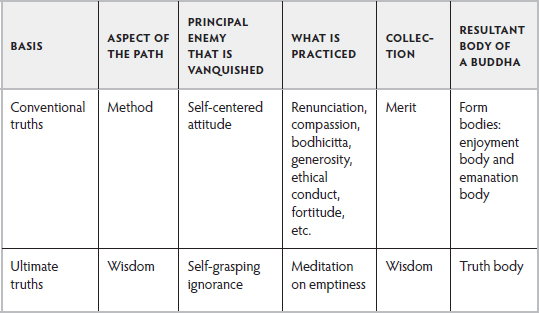

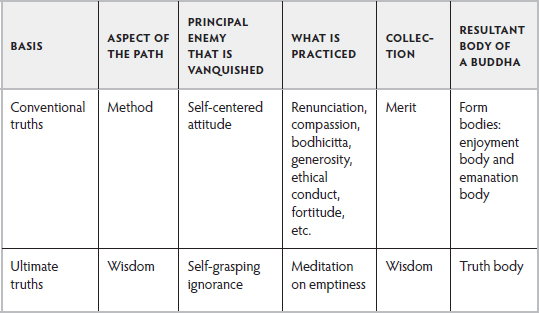

METHOD AND WISDOM are the two wings of the path that vanquish the two enemies of self-centered thought and self-grasping ignorance. As mentioned before, method refers to renunciation, bodhicitta, and all the practices we do to accumulate merit. Wisdom is the correct realization of emptiness that contributes to the collection of wisdom. These two collections—of merit and wisdom—lead to the kayas, or bodies, of a buddha. The method aspect of the path principally concerns our relationship with conventional truths—the people, things, and environments that we encounter on a daily basis, as well as all the conditioned path factors, such as generosity and so forth, that we develop in our practice. Through learning how to relate to these without clinging and with compassion, we create great merit through virtuous deeds. The collection of merit primarily leads to the form bodies of a buddha: the enjoyment body that a buddha manifests to teach the arya bodhisattvas in the pure lands and the emanation body that a buddha manifests to teach us ordinary beings. The wisdom aspect of the path principally concerns the realization of the ultimate truth—the emptiness of inherent existence that is the ultimate nature of all persons and phenomena. This wisdom eradicates self-grasping ignorance, which is the root of samsara. The collection of wisdom primarily results in a buddha’s dharmakaya, or truth body, which is comprised of a buddha’s omniscient mind and nonabiding nirvana.

This gives us an idea of the correlation of basis, path, and result with respect to method and wisdom as they are cultivated in the bodhisattva vehicle. Just as a bird needs both wings to fly, both aspects of the path need to be fulfilled in order to attain both the truth body and the form bodies. Thus, our daily Dharma practice should include both method and wisdom to be successful. This makes sense because a buddha is a well-balanced individual who has developed all excellent aspects of him-or herself. Someone who generates bodhicitta but neglects cultivating wisdom can enter the bodhisattva path, but cannot advance to its higher levels. Likewise, someone who realizes emptiness directly but lacks bodhicitta will practice the hearer path and attain arhatship, but cannot attain full buddhahood. Through practicing the method aspect of the path, bodhisattvas strengthen their minds so that when they meditate on emptiness, their wisdom has the power to eradicate all grasping at inherent existence. By meditating on emptiness, they reduce their grasping, which reduces prejudice and other blockages to generating great love and great compassion equally for each and every sentient being.

By meditating on the nonconceptual wisdom of selflessness supported by bodhicitta, we unite method and wisdom. In the tantric vehicle, the union of method and wisdom is meditating on subtle emptiness with an extremely blissful mind. This bliss is not ordinary samsaric pleasure. Rather it arises from dissolving the wind energies into the central channel, making manifest the fundamental innate mind of clear light. That extremely subtle mind is then used to realize emptiness. Through meditating on this repeatedly, the meditator actualizes the resultant form body and truth body of a buddha.

In short, this verse explains that by practicing the causes (method and wisdom), the results (the two buddha bodies) will come about. Each of us has buddha-nature, the basic potential to attain buddha-hood. Since dependent arising is infallible, if we practice the path properly, accumulating merit and wisdom, why wouldn’t we attain the causes and effects of the form body and the truth body?

Understanding that buddhahood comes about through creating its concordant causes motivates us to remain focused on creating those causes without getting distracted by doubt, attachment, or self-preoccupation. If we put energy into creating these causes, the resultant state of a buddha will certainly come. We don’t have to worry about this. If we focus too much on the result, we may become impatient, wanting to attain it immediately. This infects our mind with grasping, which becomes an obstacle to progressing on the path. However, if we are content to create the causes, the result will naturally arise. When we plant viable seeds of a beautiful flower, water it, apply fertilizer, and make sure it gets the right amount of light and heat, the flowers will grow. We don’t waste energy digging up the seeds every day to see if they’ve sprouted yet, and we don’t waste time fretting over when or if the seeds will sprout. Instead we relax and enjoy the process of creating the causes for the beautiful blossoms.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama says that one of the biggest problems for Westerners is that we expect to gain realizations quickly without having to exert much effort. Such an unrealistic expectation actually slows us down because when our mind doesn’t change quickly, we become discouraged, thinking, “I’ve been practicing one year, and my mind is still filled with anger and attachment and jealousy. When am I going to be awakened?” When discouragement sets in, we stop practicing—that is, we stop creating the causes for awakening—so obviously the result won’t come about.

It is important to have a long-term vision and have the strength of mind and the courage to work toward our final goal of full awakening for the benefit of all sentient beings. When we want samsaric pleasure, we sacrifice a lot and work hard to get it. We go to school for many years, studying late into the night, and take exams to get a degree. Then we get a job where we also work hard, even working overtime to earn the money needed to buy what we desire. We remain focused on our goal through all the ups and downs, the discomfort, the weariness, and setbacks until we finally obtain what we want. Seeing that we can work hard to obtain what we value, let’s apply that same energy and perseverance to attain our spiritual aims, which will bring lasting happiness and joy to both ourselves and others.

103

Listen! All this is but dependent arising.

Dependent and empty, they are devoid of self-existence.

Like false apparitions, they change from one form into another.

Like a ring of fire [made by a rotating torch], they are like mere illusions.

Listen! Dharmarakshita is going to tell us something important: all this is but dependent arising. In samsara or nirvana, nothing exists inherently. Even an initial understanding of this statement begins to tear our cyclic existence to shreds. At present all phenomena appear to us to exist inherently, and we assent to that appearance by grasping them to exist in that way. Inherent existence is synonymous with independent existence: in other words, phenomena existing without depending on any other factors whatsoever. Independent phenomena would be self-enclosed entities, existing under their own power, unrelated to causes and conditions, parts, the mind that conceives and designates them, and so forth. Independent and dependent are mutually exclusive: nothing can be both. Thus, if all phenomena are dependent arisings, it is impossible for them to exist independently or inherently. Thus everything we currently take for granted as existing “out there” as objective entities that are cut off and distant from the perceiving mind do not exist that way in the slightest.

What does dependent arising mean? There are different levels of dependence. All Buddhists accept conditioned phenomena—impermanent things that are produced due to their respective causes and conditions—as dependent on these causes and conditions. The Buddhist teaching on the twelve links of dependent arising embodies this principle and describes the process by which we enter cyclic existence and the way we can free ourselves from it by stopping the causal sequence of events that leads to rebirth in samsara.

Dependence on causes and conditions also means that everything we encounter around us—people, their bodies and minds, things in the environment, desirable and undesirable situations and events—all arise due to their own causes and conditions. A sheet of paper depends on trees, loggers, a paper mill, and so forth. We exist dependent on our parents, the continuity of our consciousness coming from previous lives, the previous karma we have created, and the food we have eaten. Nothing happens causelessly. Everything exists only because the causes and conditions for it existed and gave rise to it. Because functioning things are dependent on their causes and conditions, they are empty of inherent existence.

On a deeper level, all phenomena—both impermanent products and permanent phenomena, such as permanent space and nirvana—exist dependent on their parts. What we call “I” has parts—the five aggregates, the body and mind. Similarly, our body is made of many parts: it is not one partless, unified object. Our mind too is made of many moments of clarity and awareness.

Permanent phenomena are also dependent on their parts. For example, emptiness is permanent—it does not change from one moment to the next—but emptiness has different “parts”: the emptiness of the table, the emptiness of the person, the emptiness of functioning things, the emptiness of permanent phenomena.

In addition, phenomena are mutually dependent: long and short, teachers and students, causes and effect, the three times (past, present, and future)—all depend on each other. A seed could not be considered a cause unless there is the possibility of it producing its effect, a sprout. Samsara and nirvana exist mutually dependent on each other. So do a reliable cognizer and a reliable object that is cognized. The emptiness of the table is dependent on the table, the conventional object that is empty. Without one, how could we have the other? Because all phenomena depend on their parts and depend on their relationship to other things around them, they do not exist independently or inherently.

Going even deeper, dependent arising means that all phenomena depend on the mind that conceives and designates them. An easy-to-understand example of this is a person becoming the president or prime minister of a country, which occurs only after the people of that nation agree to designate that term to him or her. There is nothing inherent in that person that makes him or her the president; their having the power and responsibility of the president occurs only when that group agrees to designate him or her as such on the basis of being elected by the population.

Similarly, all phenomena exist by being designated with a term in dependence on a basis of designation. Nothing exists independently, without being merely designated by the mind. A flower exists by our agreeing to refer to the collection of petals, stigma, stamens, and filament and so forth by the name “flower.” In dependence on the association of a body and a mind, we designate “I” or “person.” While we designate a collection of parts in a particular formation as being a certain object, there is nothing in that collection of parts that is the actual object. Because all phenomena depend on being conceived and designated in dependence on a basis of designation, they do not exist inherently, in and of themselves.

For example, when an engine, wheels, axle, hood, and so forth are arranged in a particular formation that can be used to transport people and goods, we call it a “car.” That collection of parts is the basis of designation. However, when we look into that basis of designation, there is nothing that individually and in isolation can be identified as the car. And the car cannot be found somewhere separate from that collection of parts either. The car exists by being merely designated in dependence on that collection of parts. “Merely” eliminates the car having any existence that is independent of its being designated on that basis of designation.

Although we designate objects, it is as if we have forgotten that we gave them that name, and instead we believe they are that thing; we think the designated object is the basis of designation or can be found in that basis of designation. If we label a particular constellation of events “problem,” we react to it as if it were a truly existent problem. We feel heavy, burdened, and even depressed. If we call the same events “opportunity,” we relate to it in a totally different way, approaching it with eagerness and creativity. That combination of events, in fact, is in and of itself neither a problem nor an opportunity. It is empty of inherent existence.

Although we may intellectually agree that phenomena exist dependently in these ways, the way they appear to us is as if they had their own essence or nature. Our ordinary minds go along with that appearance and grasp them as existing in that way. This brings many problems, especially the deleterious arising of afflictions and the generation of polluted karma. The understanding of dependent arising is a most wonderful tool that can destroy the ignorance that grasps inherent existence, and thus dependent arising is termed the “monarch of reasonings.”

In our view, things then become very solid, leading to many conflicts. For example, border disputes between two countries that may even devolve into wars are basically quarrels over which term to call a certain segment of dirt. Do we call this piece of dirt “India” or “Pakistan”? Criminal trials are deciding what term to designate someone: “innocent citizen” or “convicted criminal.” According to the term we give someone or something, we create an image of who that person is and impute a wide array of prejudices and expectations. All of this is a product of the human mind; it does not exist inherently within a person or object.

Forgetting that we created these categories, we respond to what seems to us to be an objective reality with attachment, fear, aversion, and so on, as our mind proliferates with more and more projections dependent on the term we have designated. Realizing that countries, situations, and people are merely designated helps us to understand that they lack their own inherent nature. This gives us more mental space to clear away false projections and to relate to things in a more relaxed and realistic manner.

Many people become upset when others act in a way they consider rude. However, “polite” and “rude” are mere dependent arisings. For example, in Tibetan culture, blowing our nose the way we do in the West is considered rude; that behavior is labeled “rude.” Covering our head and face and then blowing our nose is called “polite.” In Western culture, if we put our jacket over our head and blow our nose, people would look at us strangely and consider our behavior rude. In fact, neither behavior is intrinsically polite or rude.

This doesn’t mean that we should say, “Manners are empty of inherent meaning, so let’s discard manners all together.” That would lead to chaos. Wherever we live, we relate to people according to their culture. This creates harmony and well-being in the world. However, instead of automatically calling certain behavior “impolite” or “obnoxious,” and thinking it is inherently so, we should consider that it is only labeled as such and depends on culture conditions.

It is helpful to apply this understanding to our afflictions as well. We often think of our psychological states as solid, saying, “I have suppressed anger,” as if there were concrete, permanent, unchanging anger inside of us. However, anger, too, is a dependent arising. The seed of anger—that is, the potential to become angry in the future—exists in the mindstreams of us ordinary beings. When the seed gets activated by our interpretation of external events, we experience a series of mind moments that have similar qualities—based on the exaggeration of the negative aspects of a person, situation, or thing, we want to strike at it or flee from it. We designate “anger” in dependence on these similar mind moments. Anger is only what is merely designated in dependence on those moments of mind. It is nothing more. Understanding dependent arising in this way makes us more flexible.

Because things arise dependently, they are empty of inherent existence. Because they arise dependently, they exist: they arise dependent on causes and conditions, parts, and the mind that conceives and designates them. In this way dependent arising shows that emptiness and conventional existence are compatible. Dependency negates existing from its own side; dependency also establishes existence dependent on other factors.

Everything that exists, exists dependently. If it were not dependent, it would be independent and unrelated to any other phenomena. If it were unrelated to any other phenomena, it would be difficult to say it existed, because no mind or person would perceive it.

While phenomena are empty of inherent existence, they appear to be inherently existent to our minds that are polluted by ignorance. Thus they are like false apparitions in that they appear one way but exist in another. If things were inherently existent, they would be fixed and unable to change because they would be unrelated to causes and conditions. However, in fact they change from one form into another. They are like mere illusions in that they falsely appear to have their own objective essence although they do not. If we take a torch or a stick of incense and whirl it in a circle, a ring of fire appears to be there. However, no ring of fire exists; it is only an appearance.

Only when we analyze, do we discover that what appears to be there—a ring of fire—is not there. When we don’t analyze, the ring of fire falsely appears. Similarly, when we don’t analyze, people and phenomena appear to exist out there, as objective, independent entities. Only when we analyze, do we realize they are empty of existing in that way. When we don’t analyze, however, people and phenomena appear and function. How do they exist? Dependently, falsely, conventionally, as mere appearances.

104

Like a plantain tree, life force has no inner core;

Like a bubble, life has no inner core;

Like a mist, it dissipates as one bends down [to look];

Like a mirage, it is beguiling from a distance;

Like a reflection in a mirror, it appears tangible and real.

Like fog, it appears stable and enduring.

A plantain tree resembles a banana tree; however, it is actually a bush, not a tree, and has a deceptive appearance. From the outside, it appears to have a solid trunk, which is in fact layers of leaves. For that reason, when the “trunk” is split open, it is hollow and has no core. Just as a plantain tree can easily break, our life force can also easily shatter. Externally, we appear to exist so solidly. We think of who we are at this moment as being a very real person who is impervious to death and who will live for a long time. We believe this false appearance to be true, when in fact, the life force that sustains us is fragile. We lack an unchanging inner core as well as an inherently existent nature.

A bubble looks so real, and then suddenly—pop!—it is gone. There is nothing substantial about it. Similarly our life lacks any truly existent, permanent core. While we may feel, “Here I am, real and in control,” how much can we really control? Can we prevent ourselves from falling ill, aging, or dying? Can we sit down and make our mind concentrate? To what extent can we control our emotions? In fact, our life is under the influence of causes and conditions. It does not last forever and is without an essential, stable nature. It is here one moment and gone the next, just like a bubble. Although we feel we are so important, we can die at any moment, and the world and everyone in it will continue on without us. We feel we have every right to be angry at someone who is late for an appointment, yet a hundred years from now, no one will even know our name.

We want people to remember us, to write about us, to keep photos of us for future generations to see. Is this really important? Many of the most famous people on the planet have died and been reborn in unfortunate realms. While people may talk about them now—praising their talents or fame—that doesn’t help in the least to stop their suffering if they have been born as hell beings, hungry ghosts, or animals. We want to secure our posterity and legacy, but after we die, these things do not benefit us in any way. Only our karma and mental habits come with us into future lives, and sadly we neglect cultivating virtuous traits and actions while we are alive. In short, what others think of us and our pride in our worldly attainments don’t matter at the time of death. Only the karmic seeds of our actions do. These follow us into the next life, not our photographs, trophies, and reputation.

When we look at a valley shrouded in mist, the mist seems very real. However, when we walk into the mist and bend down [to look at it], it dissipates and we don’t see it. Similarly, when we look at conventional phenomena without analyzing their mode of existence, they appear to have a findable, real essence. Yet, when we analyze them, investigating, “What is that car really?” and search for the car within the collection of parts, we cannot locate a car. The appearance of a real car evaporates. We cannot identify what exactly the car is: it is not the engine, the tires, the axle, or any other individual part. It is not the collection of parts, but it cannot be found separate from its parts either. Only a car that exists by mere designation is there. No matter how much we search, we cannot find anything more than this that is a car.

Feeling great thirst while traveling through a desert, we see a mirage. We rush toward it, thinking that water is there, but find only sand. We are equally beguiled by the pleasures of cyclic existence, believing these seemingly desirable things to be truly existent and doing whatever necessary to obtain them. We are sorely disappointed when they disappear due to their impermanent nature or when they fail to fulfill our craving due to their being unsatisfactory by nature. We thought they had an abiding essence of happiness, but they do not.

A mirage appears to be water due to causes and conditions—the sand, the sun, the angle of the light, and so forth. Similarly, the enjoyments of cyclic existence appear and exist due to causes and conditions, but no enjoyments that exist from their own side or under their own power are there. Just as desert travelers approach the appearance of water with great expectations that cannot be met, so do we approach the appearance of delightful objects with the anticipation of pleasure but discover we have been deceived by false appearances.

When we look at our reflection in a mirror, though it appears tangible and real, we know that it is not our face. Nevertheless, we may react to it as if it were, generating much emotion regarding our appearances. In the same way, we believe there is a real me and agonize about the conditions of our lives: “Why can’t I have what others have? Why are they better than me? Why are my needs and desires unfulfilled?” Yet when we investigate, we discover there is no inherently existent person there: there never has been and never will be. Exactly who, then, is the person we fret so much about? Yes, we exist, but not in the way we think we do. There is a dependently arisen person here who acts and experiences the results, but no matter where we look, an independent person who exists without depending on other factors can nowhere be found.

Morning fog in a valley appears stable and enduring, like it will endure all day, yet when conditions change, the fog lifts. Each moment the fog is arising, abiding, and disintegrating simultaneously. It cannot exist there forever even if we wanted it to.

All these examples illustrate false appearances: they appear to exist one way but in fact exist in another. Similarly, all phenomena appear to have their own inherent nature, although they do not. While such inherently existent things do not exist, dependently arisen things do. Since things function and causes produce their corresponding effects, we must pay attention to the actions we do, for they cause the experiences we will undergo.

105

This butcher enemy, the self, too is just the same;

Though ostensibly it appears to exist, it never has;

Though seemingly real, nowhere is it really;

Though appearing, it is beyond reification and denigration.

Consider the example of a tree: it looks like there’s a real tree in the yard, but in fact there is a trunk, branches of various sizes, and leaves. There is the bottom of the tree and the top of the tree. None of these parts are a tree, and the collection of the parts also isn’t a tree. A tree appears to us because we designate “tree” in dependence on these parts arranged in that particular formation. Only that merely designated tree is there, not a real tree that exists from its own side. However, when we think of our self-centered mind, our self-grasping ignorance, our low self-esteem, attachment, or resentment, they appear very real and solid to us. They certainly seem to exist with their own nature, independent of the mind that conceives and designates them.

However, none of these exist in the way they appear to our mind that is obscured by ignorance. Sometimes our low self-esteem seems so real: there is a real me who is inherently deficient, incapable, and unlovable. But look again: what we call “I” or “me” is simply a collection of different factors—a body and mind. If we search to see if I exist as something findable within the body and mind or as a totally separate entity from the body and mind, we cannot find a person. Yet, when we don’t analyze, a person appears. Although that person appears to our conventional reliable cognizer, that appearance is mistaken. The person does not exist objectively as it appears to.

Furthermore, can we isolate something that is low self-esteem? Is there a truly existent thought that is low self-esteem, or is there just a series of moments of mind that have the similar quality of criticizing ourselves? Similarly, is our selfishness solid and real? Or is it merely designated in dependence on different moments of consciousness that have the similar function of placing our own interests before those of others?

Investigate the relationship between the I that has low self-esteem and the low self-esteem itself. Am I low self-esteem? Do I have low self-esteem? If I am low self-esteem, am I one and the same as the low self-esteem? That can’t be so, because there are many aspects of me. Do I possess low self-esteem? If I do, I and my low self-esteem are two different things: I am the possessor of low self-esteem, and low self-esteem is my possession. In that case, who is the I who has the low self-esteem? Is it my body? Is it my mental consciousness? It feels like I and the low self-esteem are both objective, independent entities, yet when we look, we cannot find a distinct thing to identify as either of them.

Given how much our low self-esteem affects us, questioning its existence as an independent, identifiable entity can be unnerving. This afflictive mental state is very familiar and gives us a sense of identity that we hesitate to relinquish even though it is painful. “I’m the person with low self-esteem. Don’t tell me I have buddha potential. Don’t tell me I can do things well. Don’t tell me I’m not awful; I know I am. That’s my identity.” Grasping at a truly existent image of low self-esteem keeps us trapped, when, in fact, there is no inherently existent person or inherently existent low self-esteem that can be found when searched for.

Discovering that we do not exist in the way we thought we did may sometimes trigger fear in us. If that occurs, see the fear itself as just an appearance. Fear is simply the self-grasping ignorance putting on its firework display to distract us. We don’t need to follow the fear or believe in it. It arises dependent on causes; it is not permanent and does not exist under its own power.

In the same way, this butcher enemy, self-grasping, ostensibly appears to exist as having its own essence and existing under its own power. But it, too, cannot be found when we ask, “What really is the self-grasping?” or “To what does the word ‘self-grasping’ actually refer?” All we find is moments of consciousness that have a similar aspect. There is nothing findable we can isolate as being self-grasping.

Contemplating this gives us a different feeling about those aspects of ourselves that we don’t like and the mental states that interfere with our attaining liberation and full awakening. We see that there is no solid enemy to hate or fight with inside ourselves. There are just series of similar moments of mind that we call “anger,” “selfishness,” “self-grasping,” “low self-esteem,” and so forth.

Though an inherently existent person, inherently existent self-esteem, inherently existent self-centeredness appear, they do not exist as they appear. All these things—like all phenomena everywhere—are beyond reification and denigration in that they are neither inherently existent nor totally nonexistent. They exist dependently, as appearances, nominally. They are like reflections of a face in a mirror. Just as there is no face in the mirror, yet the appearance of a face there enables us to comb our hair, there is no inherently existent person, yet a person exists as a mere appearance. This person creates karma and experiences the results. A person that exists by being merely designated by mind cycles in samsara and attains liberation.

Reification refers to the extreme of absolutism, eternalism, or permanence—thinking that all phenomena are truly existent. Denigration refers to the extreme of annihilation or nihilism, thinking that nothing whatsoever exists. That is, reification imputes a type of existence onto phenomena that they don’t have, while denigration denies the level of existence they do have. The former doesn’t negate enough; the latter negates too much. These two ways of thinking appear to be the opposite of each other, but they actually share an important premise—both hold that if something does not inherently exist, it does not exist at all, whereas if it exists, it must inherently exist. Both confuse emptiness with total nonexistence and conflate conventional existence with inherent existence.

Nagarjuna lived in the second century, when the great majority of philosophical systems asserted inherent existence. To help people overcome this wrong view, he wrote his Treatise on the Middle Way, where he presented multiple arguments that refute inherent existence. At the same time, he explained dependent arising, showing that phenomena exist. When Buddhism first spread to Tibet, some people misunderstood emptiness and fell to the extreme of nihilism, asserting that since phenomena did not exist inherently, nothing—including emptiness itself—existed at all. Delving into Nagarjuna’s texts, Je Tsongkhapa showed that the reasoning of dependent arising disproved both reification and denigration. Even the word “dependent arising” refutes these two extremes. Because phenomena are “dependent,” they are not independent or inherently existent—this negates the extreme of reification. Because they “arise,” they exist—this disproves the extreme of denigration. In short, all phenomena lack inherent existence, yet exist conventionally, on the level of appearance, dependently, nominally.

Both the person who has fallen to the extreme of absolutism and the one who has fallen to the extreme of nihilism cannot see emptiness and dependent arising as complementary and compatible. However, when we have gained the right view, we can see that dependent arising, or nominal existence, and emptiness are two sides of the same coin. They exist together in a complementary fashion. At that time, we do not fall to either extreme view.

106

So how can there be a wheel of karma?

Although they are devoid of inherent existence,

Just as the moon’s reflection appears in a glass of water,

Karma and its effects too manifest in diverse false guises.

So within this mere appearance, I will follow ethical norms.

If things are empty, how can karma function? Emptiness does not mean nonexistence. It means lacking independent existence and implies dependent existence. It is precisely because karma is empty and lacks inherent existence that it can bring effects. If our actions and their results were truly existent, they would be self-enclosed phenomena, independent of all other factors. In that case they could not arise due to causes and conditions and could not produce results. Being produced by causes and conditions means they depend on those causes and conditions; producing results means they change due to causes and conditions.

If things were truly existent, there would be no way a seed could grow into a tree, or an infant into an adult. We could not mix various ingredients together and make a cake. Nothing would be able to function, because every phenomenon would have its own independent essence, unrelated to everything else, unable to change. It is because things are empty that they can function. As Nagarjuna said, because phenomena are empty, everything is possible.

This is expressed by the analogy of the moon’s reflection appearing in a glass of water. There is no moon in the glass of water, but the reflection of the moon appears due to causes and conditions. The reflection depends on the water, the light from the moon, and the position of the moon and the glass of water in relation to each other. While the glass of water is empty of a moon, the reflection of the moon exists as a deceptive appearance; it does not exist as it appears.

Likewise, karma and its effects manifest in diverse false guises. All the situations we find ourselves in are influenced by our previous karma. They arise in dependence upon the causes we created in the past and the particular constellation of conditions in the present. For example, the activity of hearing teachings is dependent—on the teacher’s voice, on the lineage of masters, on the room, on us understanding language, and so forth. The situation is a dependent arising. There is not one partless, isolated activity of listening to teachings; it consists of numerous moments that are in constant flux. Even though we cannot identify a single thing that is the event of listening to teachings, it is happening and will bring both immediate and long-term results. We know this, because if we spent this time watching television instead, the results would be different.

Although actions and their results exist conventionally, they cannot be found when we search for them with ultimate analysis. We cannot isolate one moment or one factor and say, “This is the action of killing,” or “This is the action of generosity.” But when we don’t search for a particular thing that the word “killing” or “generosity” refers to, we can talk about them and understand what each other means. They are appearances, existing due to the mind conceiving and designating them in dependence on a basis of designation.

Saying that things exist by being merely designated does not mean we can call something anything we want. Conventionally as a group, we have agreed to call certain arrangements of parts by a particular name and have given them specific definitions. We have agreed to call a yellow citrus fruit a “lemon.” If I decided to call it “golf ball” instead, no one would know what I was talking about, and my saying “mix the juice of a golf ball with sugar, chill it, and drink it on a hot day” would be considered gibberish. The name “golf ball” does not fulfill the definition or the function of a yellow citrus fruit.

In our normal perception, we consider happiness and suffering to be truly existent, when in fact they are also mere appearances that cannot be isolated and identified when analyzed. For example, we say, “I’m happy.” What is that happiness? Does it exist on its own? Is it in my body? In my mind? Is it a primary consciousness? A mental factor? If it is a mental factor, can this mental factor exist independently of a primary consciousness? Why did this happy feeling arise at this moment? It must have a cause; thus it is changing moment by moment and is dependent on other factors.

Furthermore, happiness and suffering are designated and identified in relation to each other. Does one exists first, or are they defined in mutual relationship to each other? Do you call a particular feeling “happiness” one day and “suffering” the next, depending on whether you have felt a preponderance of happiness or suffering the previous day? A healthy person says, “Walking is painful,” after he bumps his ankle against a pole, while a person recovering from a broken leg says, “I’m pretty comfortable when walking,” even though he has a cast on and cannot go very far. The person with the broken leg may be experiencing more pain than the one who bumped his ankle, but in relation to what he experienced when he first broke his leg and his expectations of how he should feel now, he finds the present sensation somewhat comfortable.

Even though things do not truly exist and are unfindable when searched for with ultimate analysis, within this mere appearance, we should follow ethical norms. Following ethical norms is extremely important. Selflessness and emptiness are not excuses to act according to whatever impulse arises in our mind. Rather, because actions and their effects arise dependently and are empty of inherent existence, we should pay very close attention to what we think, say, and do. People who understand emptiness respect and adhere to the law of karma and its effects very closely.

People may say, “Since everything is empty, we can do whatever we want. There’s no good and no bad.” This reflects their misunderstanding of the meaning of emptiness. They have mistaken emptiness for total nonexistence, and by throwing ethical conduct to the wind, they create the causes to experience severe suffering. Those with a correct understanding of emptiness, see that emptiness, far from contradicting karma and its effects, is compatible with it. In fact, for the wise, emptiness indicates dependent arising, and dependent arising signals emptiness. Since observing ethical conduct is the most important type of dependent arising to understand, the wise greatly respect it.

107

When the fire at the end of the universe blazes in a dream,

I feel terrified by its heat, though it has no inherent reality.

Likewise, although hell realms and their likes have no inherent reality,

Out of trepidation for being smelted, burned, and so on, I will forsake [destructive actions].

When we dream that the universe is ending with a raging fire consuming everything, we see the blaze and feel the heat, even though there is no real fire in the dream. The appearances of fire, heat, and me getting burned are there, but an actual fire, heat, and me are not present. While these appear real in the dream and we grasp them as real and react to them as real, they exist only on the level of deceptive appearances.

Similarly, in dependence on pixels on a screen, people appear on a computer screen. Are there actually people there? No. Do we respond as if they were real? Yes, we cringe when seeing refugees fleeing violence or villages struck by Ebola. We are enchanted seeing wild giraffes and lion cubs; we laugh at the antics in sitcoms. In fact, none of those are there in the screen; they are only appearances. However, these false appearances function to arouse emotions in us. Learning more about the situation of people or animals, we develop ideas about how they should be cared for, and that often motivates us to act and extend help.

While dreaming, the dream people and dream environment appear real. When watching a film, the people and their actions appear real. Likewise, when we listen to teachings, our teacher, ourselves, and the audience appear truly existent. Just as there is an appearance of fire in a nightmare and of people on a screen, but no real fire or people are actually there, there is an appearance of people at the teachings, but no truly existent people are there. Does that mean that there are no people at all? No, conventionally existent people that exist on the level of appearance attend the teachings of a dependently existing spiritual mentor.

Dreams and screens are analogies, but we should not take them too far. These analogies have the purpose of pointing out deceptive, false appearances to us. However, there is a difference between the fire in a dream and the people who are here listening to teachings with us. The dream fire cannot perform the function of burning anything, and the person on a screen cannot shake your hand. However, the people here in this room with us can shake our hands; they experience happiness and suffering. Our actions affect them. Nevertheless, they are deceptive in that they appear to be truly existent although they are not.

Although hell realms and their likes have no inherent reality, they do function as places of painful existence. If we are born there due to being reckless in our ethical conduct, we will experience suffering. Therefore, out of trepidation for being smelted, burned, and so on, we will forsake [destructive actions] and respect the functioning of karma and its effects.

As human beings, we see animals and know that the animal realm exists and beings are born in it. Do the hell, hungry ghosts, and celestial realms exist, or are they illusions like figures on a screen or in a dream? These environments and the sentient beings living in them are as “real” or “unreal” as our human realm. When beings whose minds are overwhelmed by grasping at inherent existence are born in these realms, everything appears completely real to them, and they grasp everything and everybody there to exist as inherently real as well. As in our human lives, the people and environment in the other realms, and ourselves as well, are empty of inherent existence. We suffer because we grasp ourselves, others, and environment as inherently existent, although they are not.

As in the previous verse, this verse emphasizes the importance of observing the functioning of karmic causality, even though the people and environment do not exist as they appear. Even though the hell realms do not truly exist, on a conventional level sentient beings can be born there due to destructive actions. Similarly, although human beings do not truly exist, sentient beings are born in the human realm by the force of virtuous ethical conduct.

108

When in feverish delirium, although there is no darkness at all,

One feels as if plunged and trapped inside a deep, dark cave.

So, too, although ignorance and so on lack inherent reality,

I will dispel ignorance by means of the three wisdoms.

In feverish delirium due to disturbance of the elements of our body, we feel as if we were plunged and trapped inside a deep, dark cave. Although the experience feels real, when we are aware that it is just a false appearance, we are not overcome by fear. Likewise, when we are in a bad mood, the people around appear to be particularly rude and critical, and when we feel depressed, the activities that we used to find interesting now appear useless and boring. These daily life examples show the power our mind has in creating our experiences. The situations and objects we encounter do not exist objectively “out there” as we believe them to. When we grasp these appearances to the mind as having an independent, inherent nature, they affect us strongly, and we think, “This person, from his own side, is a jerk,” or “That person is really terrific.” If these people existed objectively as they appear to us at that moment, everyone would see them in the same way. However, that is not the case. The person we adore appears dull to another person, and the person we think is obnoxious someone else loves dearly. Stopping the grasping at these false appearances as real will enable our minds to be peaceful and see others with equanimity.

All appearances in samsara—and even the ignorance that is samsara’s root—do not exist inherently. Ignorance and cyclic existence depend on each other. They are causally related and mutually related; therefore, they do not exist with their own inherent nature. Ignorance exists by being merely designated in dependence on a series of moments of self-grasping, and cyclic existence exists by being merely designated in dependence on the six realms and the twelve links.

Precisely because ignorance and cyclic existence are empty of inherent existence, they can be eliminated. Ignorance grasps at inherent existence, which doesn’t exist at all. This can be known by cultivating the three wisdoms: the wisdom of learning, the wisdom of reflection, and the wisdom of meditation. The wisdom of learning is gained through hearing, reading, and studying the teachings on emptiness. Based on that, the wisdom of reflection contemplates what we learned in order to develop a correct conceptual understanding of the meaning of emptiness. Following that, we cultivate the wisdom of meditation by focusing our mind on the meaning of emptiness until we can perceive it directly, without the medium of a conceptual appearance. This wisdom knows the lacks of inherent existence, which is directly contradictory to the inherent existence that ignorance erroneously perceives. As our mind becomes more and more familiar with this wisdom, it cuts away the layers of ignorance, until finally ignorance is completely eliminated. At that point, the afflictions based on ignorance no longer arise, and karma causing cyclic existence is no longer created. In this way cyclic existence comes to an end, and nirvana is attained.

109

When a musician plays a song of ecstasy,

If probed, there is no inherent reality to the sound.

Yet melodious tunes arise through the aggregation of unexamined facts

And soothe the anguish lying in people’s hearts.

When a musician plays a song of ecstasy, where and what is that song? Is it in the musical instrument? In the musician? Is it the sound waves in space or the sound waves when they touch our ears? Is the song one note? A collection of notes? If probed, there is no inherent reality to the sound, yet the song still exists—the melodious tunes arise through the aggregation of unexamined facts. The individual sounds arise due to causes and conditions, and when they arise in a certain order, they form a song. Even though neither the sounds nor the song are findable under analysis, they still function to soothe the anguish that lies in people’s hearts.

On the other hand, if the musician, the notes, and the song existed inherently as they falsely appear to, how could they function to bring joy to others? Someone could be a musician without depending on playing a musical instrument; the song could exist without the musician playing the instrument, and the instrument could play music without there being a musician or a song. Such are the logic conundrums of asserting that things exist from their own side or under their own power.

110

Likewise when karma and its effects are thoroughly analyzed,

Though they do not exist as inherently one or many,

Vividly appearing, they cause the rising and cessation of phenomena.

Seemingly real, one experiences joy and pain of every kind.

So within this mere appearance, I will follow ethical norms.

Similar to the example of the song, when we apply ultimate analysis to karma and its effects—looking at how they exist and what their ultimate nature is—we discover that they are empty of inherent existence. When we try to identify exactly what an action is and its effects are, we cannot find things that exist independent of each other or of everything else. Instead, we find only their emptiness. This emptiness does not contradict the conventional existence of karma and its effects; in fact, it supports and complements it by showing that while they lack inherent existence, they arise dependent on other factors, such as their own causes and conditions.

If an action were inherently existent, it would have to be either inherently one or inherently many. There are no other options: it can’t be both one and many. Let’s take the example of speaking harshly to somebody out of anger. Is that action of speaking harshly one inherent thing or many inherent things? There are factors contributing to the action—the perception of the other person’s face, the sound of his or her voice, our thought (“He can’t speak to me like that!”). Then there is the motivation to put the person in his place, the brief contemplation of how to word our response so it has the most hurtful effect, our mouth opening, the words coming out, the completion of the angry stream of words, and the other person hearing it. Investigating in this way, we see that the action of harsh speech is not one thing with exact, well-defined borders. Rather, there is a sequence of different events.

If it is not one thing, then is it many things? If it were many things, then how come we say it is one action of harsh speech? In addition, if the action of harsh speech were many actions, then which of those many actions would it be?

When we analyze an action or karma, we see it is neither an inherently singular action nor an inherently multiple action. Thus it is empty of inherent existence. However, it does exist dependently, by being merely designated in dependence on the collection of various events. In the same way, the results of our actions—for example, the feelings of joy and pain we experience—are neither inherently one nor inherently many. Although we cannot isolate inherently existent causes or inherently existent effects, the law of cause and effect still functions. We know from our own experience that certain actions bring particular results. Therefore, it is important to observe the functioning of the law of karma and its results.

The Tibetan phrase here translated as one or many can also be translated as “one or different.” This involves an analysis of the relationship between the designated object—for example, an action—and its basis of designation (its many parts). Is the designated object inherently the same as the basis of designation, or is it totally unrelated and separate? The same analysis can be applied to the result—the joy or pain experienced as a result of that action. Are those feelings identical with their basis of designation, or are they totally different from them?

Let’s consider the generous action of making a donation to a charity. If that action existed inherently, it should be findable either within its basis of designation—the parts of the action, such as its motivation, the object given, the recipient, the action of giving, and the completion of that action of giving—or totally separate from those. Again, there are no other options: in terms of inherent existence, two things must be either identical or totally separate. When we investigate closely, we see that the action of making a donation cannot be identified with just one element of the scenario—giving is not identical to the motivation or to the gift or to the recipient, the action, and so forth. Giving is not identical to any of the parts of the action: holding the object, extending our hand, or releasing the object. Nor can the act of giving be identified separate from those. When we analyze and see that things are neither inherently one and the same, nor inherently separate from their basis of designation, we can safely conclude that they do not inherently exist.

When we apply the same analysis to the effect—the happiness experienced as the karmic result of generosity—we cannot find happiness in any of the individual mind moments of pleasurable feeling. Nor is happiness found separate from those mind moments. It is empty of existing by its own nature.

We can also analyze the relationship between the causal action and the resultant happiness. Does happiness exist in the action at the time the action is occurring? If it did, cause and effect would exist simultaneously, which is impossible. Does happiness arise from an inherently other phenomenon totally unrelated to that action that caused it? No, it cannot be identified there, because then any kind of action could produce happiness, and that certainly isn’t the case. Is happiness inherently identifiable within both its cause and as something separate from its cause? No, that doesn’t make sense. Does happiness arise without a cause? Certainly not, results are not random occurrences. Seeing that the result, happiness, cannot be found inherently in any of these ways, we conclude that is does not exist inherently. Nevertheless, we feel happiness and pain; these results do exist.

We do not plant crops in the spring, thinking nothing is going to happen; we plant crops because we know that seeds produce plants. We plant corn to get corn; we plant daisies to get daisies. In the same way, we want to create the causes for future lives. To “grow” happiness in future lives, we engage in virtuous actions now. If we want the results of liberation and awakening, we have to “plant” the causes of merit and wisdom now. We do not think, “Everything is random, so it doesn’t matter what seeds I put in the ground.” Similarly, we want to be careful what kind of karmic seeds we “plant” in our mindstream.

Karma and its effects, causes, and conditions are intricately involved: the rising and cessation of phenomena. We are born and die. Relationships come together, change, split apart, and new ones begin. These things vividly appear to arise and perish, but none of them exists as a self-enclosed, objective event. We experience happy, painful, and neutral feelings, but these experiences do not arise under their own power. Dependent, they arise due to causes. They are mere apparitions in the sense that when we investigate them with ultimate analysis, we cannot find them, yet when we do not investigate, they appear and function.

111

When drops of water fill a bucket,

It is not the first drop that fills it,

Nor the last drop, or each drop individually.

Through the gathering of dependent factors, the vase is filled.

112

Likewise when someone experiences joy and suffering, the fruits [of karma],

This is not due to the first instant of their cause,

Nor is it due to the last instant of the cause.

Joy and pain are felt through the coming together of dependent factors.

So within this mere appearance, I will observe ethical norms.

The example of the drops of water filling the bucket illustrates the dependent nature of causes and their effects. Neither the cause nor the effect can be isolated as a self-enclosed entity, yet both exist and function. One drop of water—be it the first drop, the last drop, or one in the middle—does not fill a bucket. Yet the bucket is filled depending on many drops, all of which must be present. If one is missing, the bucket will not be completely full.

Similarly, the result of an action—the experience of pleasure or pain—is not due solely to the first moment of the cause, the last moment, or any moment in between. Rather, all the moments of causal energy and all the various factors contributing to an action must come together in their own unique arrangement in order to produce that specific feeling of joy or misery. When we think of the complexity of the countless causes and conditions that assemble for each moment of our experience, it is mind boggling.

Our first introduction to the idea of karma and its effects is usually done in a simple manner. Our parents tell us, “In the sandbox, if you throw sand in someone’s face, he’ll throw sand in your face, so don’t do to others what you don’t want to experience yourself.” Later the explanation expands to include future lives: “If you speak rudely to that person, someone will speak rudely to you in a future life.” We then come to understand that karma and its effects is not a tit-for-tat affair always involving the same people. Our uttering of harsh words plants the seed in our mindstream to hear harsh words sometime in a future life. However, the person who criticizes us will not necessarily be the person we criticized; it may very well be someone else. Many other causes and conditions must come together for that karmic seed to ripen into that result.

The functioning of karma and its effects is not rigid. Conditionality allows room for change. For that reason, the environment we choose to put ourselves in and the actions we choose to do now are important for they will influence which karmas will ripen. If a person caused serious physical harm to someone in a previous life, there is a karmic seed on his mindstream that could ripen in his getting in a traffic accident. If he drinks and drives, he is creating the cooperative conditions for that karma to easily ripen. On the other hand, if he does purification practice, he can forestall the ripening of the karma or lessen the severity of the result. Perhaps that karma will ripen in his tripping instead.

Our being on the receiving end of harsh words is but one result of that action. As explained earlier, if the action of our speaking harshly is complete with preparation, action, and completion, it will also ripen in our being reborn in a certain realm, the habitual tendency to speak harshly, and the environment we live in. The functioning of karma and its effects is complex and many elements are involved, so much so that only an omniscient buddha is able to know the specific causes and conditions leading to a specific result or constellation of results in an individual’s life.

This verse emphasizes once again that even though joy and suffering are empty of inherent existence, they exist dependently. Causes are created and results are experienced all within the sphere of emptiness. Since our experiences arise due to causes that we ourselves have created, we need to pay attention to our actions, realizing that they have an ethical dimension. It is within our ability to create the causes for the kind of lives we want to have in the future, for our liberation from cyclic existence, and for our full awakening. In the sutras, the Buddha explained what the causes for each of these are, and the great Indian masters fleshed out the details. The great Tibetan masters systematized these teachings and further commented on them. It is up to us to study and practice the instructions of this liberating path that we are so fortunate to have encountered.

When we do so, we learn that creating the causes for good rebirths involves taking refuge in the Three Jewels and then ceasing the ten nonvirtuous paths of action and engaging in the ten virtuous ones. The causes for liberation are the three higher trainings in ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. The causes for full awakening are generating bodhicitta, engaging in the six perfections—generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude, joyous effort, meditative stability, and wisdom—and eventually the tantric path.

113

Ah! So utterly delightful when left unanalyzed,

This world of appearance is devoid of any essence;

Yet it seems as if it really does exist.

Profound indeed is this truth, so hard for the weak to see.

When left unanalyzed, conventional things are delightful to use and experience. We can talk about agents who act, the actions they do, and the objects acted upon. There are a pitcher, a batter, and a baseball. There are friends and good conversations, projects to do and people to work with to accomplish them. All these daily life objects function, and we communicate about them.

However, when analyzed, this world of appearance is devoid of any essence. When we walk into the room, the apple on the table seems real, existing in and of itself. But when we investigate the apple with ultimate analysis to find out what it really is and how it really exists, we see that it lacks its own identifiable essence. If the apple had a findable essence, the more we examined it, the more obvious that essence would become. However, the opposite happens. When we ask, “Is the apple the peel? The core? The flesh? The top side? The bottom side?” we cannot identify anything that is an apple. There are only parts, none of which is an apple. Yet, when left unanalyzed, we say, “Here’s an apple for you to eat,” and the other person knows what we’re talking about and eats the apple and enjoys it.

The apple exists dependent on many parts and causes, all of which are “non-apples.” How strange that when many “non-apples” are put together in a certain arrangement, suddenly an apple appears by being merely designated! The apple appears but is empty. It is empty of its own essence, yet it appears. Profound indeed is this truth, so hard for the weak to see.

The same applies to our bodies, emotions, thoughts, and opinions. All these things that appear so real, that we believe we have to defend from harm, are similar in appearing when left unanalyzed and being unfindable when searched for with ultimate analysis. I and mine are similar: they seem so real and important, yet they vanish when we try to identify exactly what they are. Understanding this deeply gives us a newfound spaciousness in our minds.

114

Now as I place my mind on this truth in total equipoise,

What remains certain even of this mere appearance?

What exists and what does not exist?

What thesis is there anywhere of “is” or “is not”?

The mind placed on this truth in total equipoise is a special state of meditation that is the union of serenity (shamatha) and insight (vipasyana) that is focused on the emptiness of true existence. This is a nondual meditative state, free from the appearance of subject and object—of the mind as the perceiving subject cognizing a separate object, in this case emptiness. This nondual meditative state has no appearance of inherent existence or of conventional objects. In addition, there are no conceptual appearances at that time because the meditative equipoise directly perceiving emptiness is a totally nonconceptual consciousness.

Until that time, all phenomena have appeared to us as truly existent. When meditators are in this meditative concentration that directly perceives the lack of true existence, the only thing appearing to that mind is emptiness. Perceiving only emptiness, which itself lacks inherent existence, the mind and its object are merged like water poured into water, indistinguishable. This extremely peaceful, penetrative state of meditative wisdom counteracts the ignorance that is the root of cyclic existence.

Although this state of nondual meditation does not perceive conventional objects, that doesn’t mean they no longer exist. Rather conventionalities are not in the purview of this nondual wisdom. For example, our auditory consciousness cannot perceive colors, yet this does not negate the existence of colors because colors are not the object of an auditory consciousness. They are the object of a visual consciousness. Similarly, conventionalities are not the object of ultimate analysis or of direct perceivers of emptiness. These ultimate consciousnesses do not negate the existence of conventional things; it negates only their inherent existence. The lines in the Heart Sutra, “There is no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, and no mind,” and so forth refer to meditative equipoise on the path of seeing when we have our first direct, nonconceptual perception of emptiness. To that mind, none of these other things appear. However, when these meditators arise from their meditative equipoise on emptiness, conventionalities again appear.

Before meditators have realized emptiness directly, they believe that everything—people, phenomena, samsara, nirvana—exist inherently. Upon perceiving emptiness directly, they realize that this is not true and that it has never been true. That is, perceiving emptiness does not make phenomena empty; they have always lacked inherent existence and only now is their ultimate nature known. However, when these meditators—who are now known as aryas—emerge from meditative equipoise, the appearance of subject and an object returns, as do the appearance of true existence and the appearance of conventionalities. Although in the postmeditation time, aryas see things that appear inherently existent, they do not assent to this appearance by grasping them as inherently existent. Thus it is exceedingly difficult for attachment, anger, arrogance, jealousy, and all the other afflictions to arise in their minds.

What exists and what does not exist? The emptiness of inherent existence exists and is known by a reliable cognizer apprehending ultimate truths. Conventional truths, which exist falsely in that they appear truly existent although they are not, exist and are apprehended by conventional, reliable cognizers. Inherent existence, however, does not exist.

What thesis is there anywhere of “is” or “is not”? refers to Nagarjuna stating that he did not have a thesis. Many people misunderstood that statement to mean that Madhyamakas do not believe in anything and make no positive statements at all, they only negate. This is not correct. Rather, Nagarjuna does not make any truly existent theses; all theses he makes exist only conventionally.

115

There is no object, no subject, nor ultimate nature [of things].

Free of all ethical norms and conceptual elaborations,

If I abide naturally with this uncontrived awareness

In the ever-present, innate state, I will become a great being.

To review, while nothing exists inherently, phenomena do exist conventionally; they vividly appear when not searched for by ultimate analysis. There is no [inherently existent] object or subject, and even emptiness, the ultimate nature, lacks inherent existence. All these conceptual elaborations of true existence never existed and do not appear to the mind of meditative equipoise on emptiness, which perceives ultimate reality. Ethical norms, which depend on words and conceptuality, also do not appear to the meditative equipoise on emptiness. However, they exist conventionally and are established by conventional, reliable cognizers. Although ethical norms do not exist inherently, they exist dependently. As discussed before, constructive and destructive actions are so designated in dependence on the pleasant or painful effects they respectively bring about.

Misunderstanding the meaning of emptiness, some people think that since ethical norms do not exist inherently, once emptiness is realized we need not follow them. These people proceed to do whatever they like, reveling in unconventional behavior. Mistakenly thinking they are free, they “freely” create the causes for unfortunate rebirths. Their actions create chaos now and bring suffering results in the future as well. To prevent this, Dharmarakshita, in several of the previous stanzas, spoke of the importance of keeping precepts and holding to ethical norms. While virtuous and nonvirtuous actions are empty on the ultimate level, they function conventionally, and causes indisputably bring results.

If . . . with this uncontrived awareness that does not fabricate inherent existence, I abide naturally . . . in the ever-present, innate state, without clinging, grasping, and conceptuality, we will become a great being, a mahasattva, somebody who crosses over to the other side and is free of cyclic existence and the two obscurations.

116

Thus by practicing conventional bodhicitta

And ultimate bodhicitta [as well],

May I accomplish the two collections without obstacles

And realize perfect fulfillment of the two aims.

In this verse, Dharmarakshita gives us his final advice and encouragement to study, reflect, meditate on, and actualize the path to full awakening. By practicing the conventional bodhicitta (the aspiration to become a buddha in order to benefit sentient beings most effectively) and ultimate bodhicitta (the wisdom directly realizing emptiness), we will complete the two collections of merit and wisdom. The resultant state of buddhahood is the perfect fulfillment of the two aims: the aim of self and the aim of others.

The aim or purpose of self refers to the truth body (dharmakaya) of a fully enlightened being, the omniscient mind that is completely free from all obscurations and directly perceives all phenomena, both conventional and ultimate. The aim of others is the form body, the manifestations of a buddha that directly benefit sentient beings. With form bodies, a buddha is able to guide sentient beings to temporal and ultimate happiness, especially by teaching them the Dharma. In this way form bodies fulfill the aim of others.

Thus Buddhist practice involves working for our own and others’ goals and happiness. Our ordinary view believes our own happiness and that of others as separate—if others have something good, I will not have it. We believe that since objects of enjoyment are finite, if someone else obtains a wonderful possession or situation, that means we will not have it. Our ordinary mind also thinks that if we work for others’ welfare, we’ll have to sacrifice our own happiness and thus will abide in a state of misery—that working for our own benefit and working for others’ benefit are incompatible and contradictory. This view is very narrow, and adhering to it traps us in a prison of our own making. In fact, there is not a limited amount of goodness and joy, such that if others have it, we do not. Rather, the more goodness and wisdom there are, the more there will be. The more we cherish others and work for their welfare, the happier we will be. The buddhas work for the benefit of others, and their happiness and bliss is so much greater than the happiness of ordinary beings who seek their own welfare.